CHAPTER 3

AN ALIGNING NARRATIVE

“Cephalopod” is a fancy name for a mollusk with tentacles, like a cuttlefish or octopus. Uniquely, much of their nervous systems are not concentrated within their brains (like ours) but are instead distributed throughout their bodies. In an octopus, for example, the majority of its neurons are in its tentacles—nearly twice as many as can be found in its central brain.

As a result of this distributed nervous system, an octopus’s body parts think and act somewhat free from the central brain’s direction—to sometimes disconcerting extents. Researchers can surgically remove a tentacle yet still watch the now-severed arm not only move off by itself but also grasp any food it comes across and attempt to pass it back to where the octopus’s mouth would be were the tentacle still connected to the body. Each appendage seems to be able to “think” for itself and make decisions on how best to react to what it comes across, and yet when attached to the octopus’s body, they coordinate their efforts in such a way as to never tangle with one another.

When I joined the Task Force, I joined a masterfully designed bureaucratic military, a top-down vertebrate with the thinking at the top and the actions at the limbs. We encountered in Al Qaeda a distributed cephalopod, whose limbs could continue to act when severed and whose position on the main body quickly regenerated. Facing such a threat, our top-down alignment structure was insufficient.* We all knew on some level that our singular mission was to defeat Al Qaeda, but our teams, when empowered to act autonomously, too often accidentally worked against one another.

If we were to become a hybrid model that maintained top-down alignment while also empowering our individual teams to make coordinating autonomous decisions, each team would need a deep enough understanding of strategy to operationalize it without top-down direction. To do this, we needed to create a powerful narrative that not only would unite our teams on our organization’s single mission but would also tell them how to achieve that mission.

PROBLEMS WITH TRADITIONAL APPROACHES TO STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT

The idea of strategic alignment is not new; for years, bureaucratic organizations running on a traditional model have worked to make sure their teams are strategically aligned. However, in most cases this alignment comes from the top, and our experiences in the Task Force showed that a traditional top-down approach to vertical strategic alignment can actually mask horizontal misalignment and further fuel narrative divide among teams.

In a traditional business model, the company runs like a crew rowing a racing shell, to borrow an analogy used by Robert Kaplan and David Norton, developers of the “Balanced Scorecard” system. Not only are the parallel crew members horizontally aligned in that they do not disrupt one another’s strokes as they row, but they are also vertically aligned in that their combined actions jointly contribute to the overall direction and velocity of their boat.

Kaplan and Norton compare the coxswain’s role in a crew to that of corporate headquarters. The leader of the racing shell steers the boat and monitors the cadence of the strokes, providing a uniting force to the team on both vertical and horizontal planes. Similarly, the strategic leadership of an organization monitors every silo’s actions, motivating them accordingly and ensuring they do not conflict with one another.

This top-down approach has been the standard for strategic alignment since iconic management figure Peter Drucker popularized “management by objectives” through his 1954 tome The Practice of Management. In it Drucker argued that each of an enterprise’s teams needed to be able to work toward clearly defined, often self-guided goals that stack upon one another to better achieve the organization’s overarching long-term strategy. His description channels Weber:

Business performance therefore requires that each job be directed toward the objectives of the whole business. And in particular each manager’s job must be focused on the success of the whole. The performance that is expected of the manager must be derived from the performance goals of the business, his results must be measured by the contribution they make to the success of the enterprise. The manager must know and understand what the business goals demand of him in terms of performance, and his superior must know what contribution to demand and expect of him—and must judge him accordingly. If these requirements are not met, managers are misdirected. Their efforts are wasted. Instead of team work, there is friction, frustration and conflict.

Vertically cascading alignment like this is a relatively straightforward process, allowing strategic leaders either to individually frame their organization’s different objectives or to delegate ideas on how different silos should interact, down a solid-line org chart. But there are drawbacks to placing ultimate decision-making power in the hands of those at the top of the bureaucratic org chart.

Remove the coxswain’s guidance from a crew, and inexperienced rowers may descend into misalignment and poor pacing. Similarly, without senior leadership calling the shots, a company’s silos may end up misaligning their efforts if the company is operating in a complicated environment. And if the organization is dealing with complexity, traditionally structured teams will certainly lose their alignment if the top-down communication ceases.

In their Harvard Business Review article “Why Strategy Execution Unravels—and What to Do About It,” Donald Sull, Rebecca Homkes, and Charles Sull note that the traditional approaches to alignment—“translating strategy into objectives, cascading those objectives down the hierarchy, measuring progress, and rewarding performance”—are insufficient to unite a team on one mission. In fact, though they seem to maintain some measure of vertical alignment, they may actually damage horizontal alignment.

In the hundreds of interviews Sull, Homkes, and Sull conducted over the course of nine years, 84 percent of managers expressed confidence in their ability to rely on and trust their solid line–connected bureaucratic superiors or subordinates—but responses reflected serious problems with horizontal alignment; only 9 percent of managers surveyed felt they could “rely on colleagues in other functions and units all the time.” Additionally, managers reported that cross-functional collaboration was “handled badly two times out of three.”

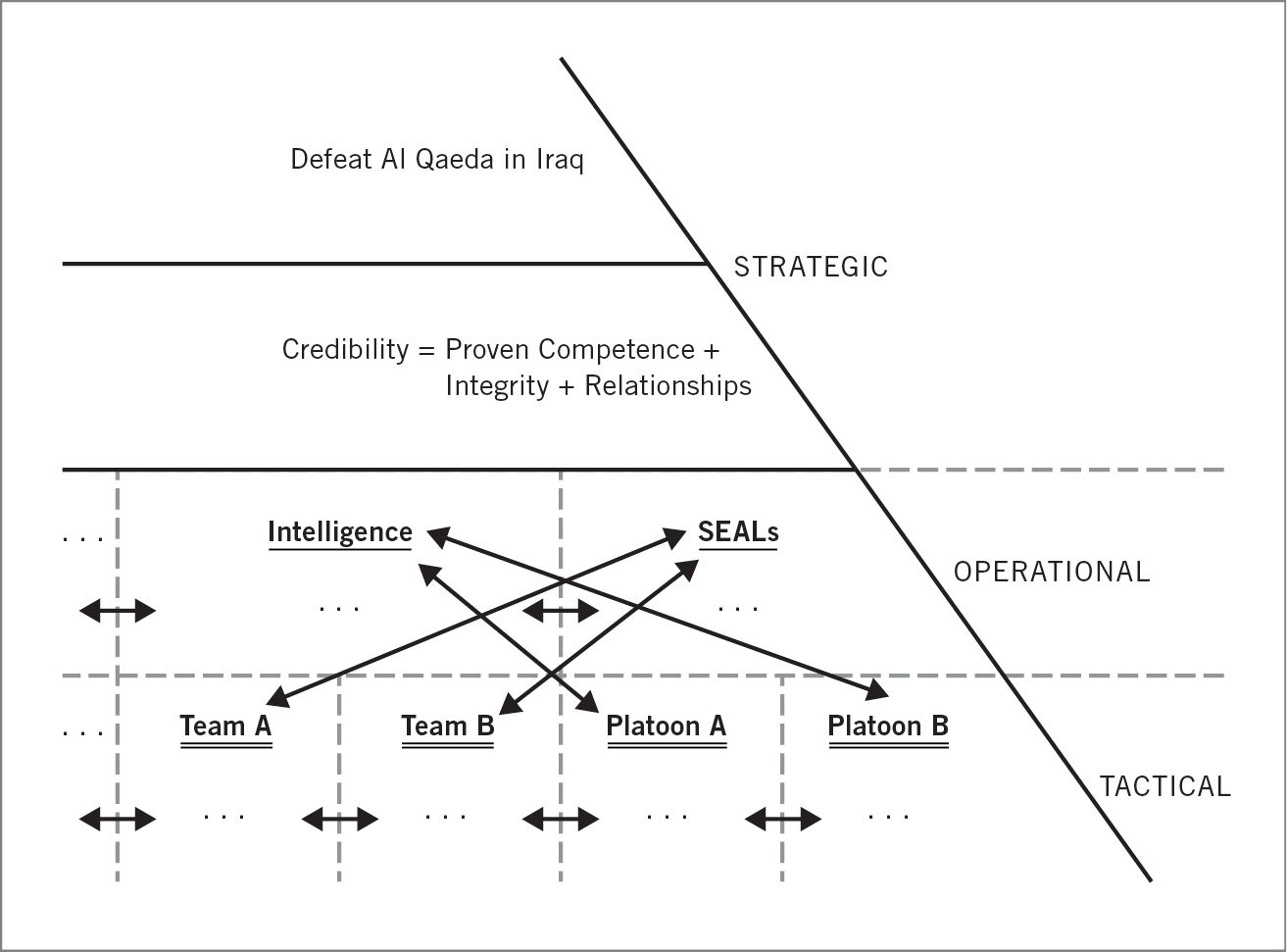

Our experiences in Iraq mirrored these problems. As complexity increased, so too did horizontal gaps and resultant mistrust among silos. In the early days, it seemed that the Task Force’s strategic leadership set a relatively clear guiding objective for our organization. From my perspective, the ultimate, obvious goal that our organization’s teams were expected to “self-guide” upon was to “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq.” We believed that strategic leadership could announce this goal and that it would cascade down to the intelligence officers who worked at an operational level and further down to the operators who moved us forward on the tactical level. We can better picture this cascade through the use of an alignment triangle.

But this direction to “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq” was the equivalent of a multinational firm’s dream of “winning market share” or “earning higher levels of customer satisfaction than our competitors”—a lofty, certainly worthwhile goal, but one that is unfortunately bland and narrowly communicated. As a result, this open-ended, vaguely unifying objective actually served to reinforce disconnects among teams in our enterprise, for “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq” actually meant different things to different subordinate silos, which worsened horizontal alignment.

In the Task Force’s case, my interpretation of a singular mission to “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq” could feasibly be twisted to serve my unit’s own narrative of what was needed, in our view, to win the broader war. Each of us would inevitably retrofit this mandate from senior leadership to augment our preexisting tribal narratives, as I did in my SEAL unit, where “Did you earn your trident today?” was the filter through which we viewed our strategic direction.

With little transparency and few direct lines of communication between our teams and leaders, each of us could use our organization’s overarching objective to feed our myopic view of the fight. This strengthened the already-powerful bonds among our clustered teams but weakened connections with the broader Task Force. This was repeated across our enterprise’s lattice of teams, narratives, and cultures—leading to conflicting strategic eforts.

Our state of vertical alignment appeared to be fine on the surface level. Our organization’s silos could, in a manner that Drucker might have approved of, independently ascribe metrics and quantitative goalposts to the overall objective, but would do so in a way that reinforced the individual tribal narratives of the respective teams. Of course, our strategic leadership would retain approval authority over these proposed goalposts, keeping everything ordered and controlled.

On paper these added up to a cohesive plan, but in practice the lower goals that our many siloed teams would pursue in the effort to “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq” would inevitably create intertribal conflict. Gradually, despite the fact that teams were consistently meeting their managed objectives, it became obvious that we could have high batting averages but lose the game. As we met our metrics, the violence around us spiraled out of control. Our networked enemy was not fighting us at our strongest points but instead navigating to the gaps.

Without a new type of nuanced management by objectives, one that placed just as much emphasis on lateral, informal information highways as it did on vertically approved, solid-line pathways of approval and authority, we were in trouble—and I remember the first time I realized just how severe this was in the Task Force.

KHOWST

“Chris, are you around?” The handheld radio on my desk crackled.

“Roger,” I replied. “What’s up?” I recognized the voice. It belonged to a friend of mine from a civilian intelligence team whose headquarters were located just a few hundred meters away.

“Your team’s monkey . . .” the voice on the radio came back. “She just stole our laundry.”

“On it,” I replied with mock intensity. I got up and walked out of my office into the bleaching midday sun of Afghanistan.

It was 2004, and I was based on a small compound on the edge of Khowst—an arid city located on the country’s eastern border. It was my first deployment as a part of the Task Force, and the organization was still in the extremely nascent stages of changing its operational approach. Conversations about changing our internal culture were just starting to happen among our senior leadership, but these had not percolated down into tangible changes at our tactical levels.

Our compound sat on the edge of a long-abandoned Soviet airfield with rusted, decaying skeletons of aircraft from past wars scattered around its perimeter—some of which I could recognize, like the bulbous Mi-17 transport helicopter. My morning run, which consisted of laps around the mile-and-a-half outer loop of the base, wove between these wrecks, closely hugging the twelve-foot-high meshed HESCO barriers that lined our compound.

The monkey I pursued had been living in the compound for at least a year, passed down among the Task Force’s operators as we rotated deployments, and she’d become a mascot of sorts. Recently, perhaps bored with our area of the base, she’d gotten in the habit of running along the compound’s Tetris-block walls and stealing clothes off of the laundry lines of other units. It wasn’t uncommon for our intrabase radios to come alive with a complaint about some simian shenanigans.

Responding to the radio call, I started walking across the compound with a half-eaten banana in hand, intent on winning back the monkey’s attention. As I walked, I stared to the east, at the permafrost-tipped mountain range ever visible on the horizon. Beyond those peaks lay the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan.

The FATA was, and remains to this day, an ungovernable space on the Pakistani side of the border. It was there where pockets of anti-Coalition fighters sat, enjoying sanctuary in that rugged no-man’s-land separating these two ancient nations. Over there, opaque enemy networks found the freedom to execute attacks against us, dropping mortar shells in our general direction whenever they pleased. Their accuracy, thankfully, wasn’t great; but it seemed that they weren’t trying to strike us directly, but instead to remind us that they were safe, secure, and waiting.

The outstation in Khowst hosted an eclectic mix of personnel, who, in accordance with the teachings of thinkers like Weber, Sloan, and Taylor, were compartmentalized across different teams, each beholden to a different narrative about our collective mission. As I walked through the compound and passed the various cordoned-off sections of the base that were each unit’s territory, I could see firsthand where one unit’s narrative ceased to apply and another’s began.

A few hundred yards away from my team’s annex, intelligence analysts from civilian agencies were working to develop a network of locally sourced informants, trying to get a better understanding of the membership of those FATA-based insurgent cells. At the far end of the airfield, a conventional unit—standard infantry soldiers—had been tasked with managing infrastructure reconstruction projects in nearby towns, and so were regularly patrolling outside our compound, interacting with the local populace. On another side of the base, a small team of Army Special Forces soldiers held another center of operations, while integrated across that entire mix was a yet-more-motley assortment of Afghan soldiers, early manifestations of the larger Afghan National Army (ANA) that the Coalition would try to build up in the near future.

The people who made up these teams were outstanding professionals, easy to relate to, and exceptionally dedicated to their jobs. We were all in the same conflict, sharing common facilities, and facing similar pressures to advance our efforts. To distant strategic leaders, these overlaps gave the impression that we were synergized. But despite appearances to the contrary, the units that shared the Khowst compound were poorly interconnected and uncommunicative on matters of true substance.

Unfortunately, it was difficult for us to see this, because the Task Force’s examinations of alignment tended to be of the “congressional hearing” style, where our organization’s leaders would ask high-level questions of their subordinates. If the answers matched what the examiners want to see, they often wouldn’t notice that empirical evidence pointed to an inconvenient truth. These kinds of examinations don’t succeed, because they are calibrated to measure vertical alignment only, and miss the evidence of horizontal misalignment altogether.

Consider the discussion that occurred in the Capitol in Washington, D.C., on January 13, 2010, among Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein, JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon, Morgan Stanley chairman John Mack, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan, and the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) of the U.S. Congress.

The Commission, a ten-person council of congressional leaders, had organized this initial three-hour gathering to supplement its investigation into the factors contributing to the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. But the Republican vice president of the Commission, California representative Bill Thomas, wisely pointed out the limited utility of the hearing. As he argued, the hearing would not be able to see the “7/8ths of the iceberg underwater,” and he was right. Opening comments from those testifying scratched only the surface of factors that contributed to the financial crisis. This was no one’s fault but simply a by-product of how difficult it is, in a normal process review, to truly tease out the realities of a complex and interconnected system.

A congressional hearing–style test for connectivity among our teams in Afghanistan would have had similar results. Had the Task Force’s leaders administered such a hearing to the teams at Khowst, it would have appeared that our efforts were perfectly aligned. Senior solid-line officers would have asked broad questions of their assembled subordinates, who would have presented a unified front and given prepared answers supporting what senior leaders expected to hear: teams are aligned, sharing information effectively, and working together. But this would have been only half true: whereas our Druckerian metrics did in fact vertically align with the strategy of our parent organization, our horizontal alignment was ineffective. What would have prevented us from disclosing this in a congressional hearing–style test for alignment—similar to that of the FCIC—would be a mix of social pressure, frustration with the narrow questioning, and nervousness about disappointing solid-line leaders.

But had our leadership isolated personnel from one another and initiated a non-blaming, unassuming series of deeper questions, the truth would have quickly emerged. Less guarded, more spontaneous answers regarding the state of alignment among our teams would have been offered. These could have taken the form of open admissions on poor horizontal alignment (You know what? To be totally honest, sir, we don’t really have the communication or exposure we need with those guys) or honest revelations about the narratives that existed at the small-team levels in our organization (This is how we actually think through problem sets we encounter and who we try to go to in our organization for help in solving them) or frank finger-pointing (What baffles and frustrates us is that those guys don’t talk to us, seem to misunderstand our work, and won’t show up when we need them to). This approach would have found contradictory views, each of which was correct in the eyes of the person offering comment.

Much like the parable of the blind men and the elephant, our various elements were each seeing individual parts of a complex and constantly changing puzzle, which was always placing new and fresh demands on them to work closely with one another. Our intelligence teams were gleaning snapshots of the insurgency’s growing influence on criminal networks in both Afghanistan and Pakistan, while our conventional and Task Force units were getting a growing sense of these networks’ increasing ability to move across the border, and the experiences with Afghan soldiers on base were indicating a steady rise in the insurgency’s ability to disrupt our recruitment of local fighters.

The significance of any one of these activities might have been painfully obvious to the team monitoring it, but tying these smaller events into a fully contextualized picture, which could better inform the operations of all of our teams, required a level of personal relationship–based interconnection among us that didn’t exist and that our senior leadership couldn’t perceive the need for.

It wasn’t necessarily personal animosity that kept us apart. Many members of these distinct teams were friendly with one another. Rather, it was the impersonal bureaucratic stove-piping that prevented us from pooling our knowledge or interacting on a deeper level upon it.

In pursuit of our mascot, I finally arrived at the intelligence team’s wing of the base and spotted the primate perpetrator. With a half banana in hand, I moved to coax her off her perch and away from the precious clotheslines. She was sitting atop a tall wall that ringed an intelligence team’s workplace, and—hearing them moving about in the courtyard on the other side—I yelled across to the analysts, “Sorry, fellas.”

A cipher-locked door sat between us, a security feature that represented the broader cultural and operational divide that was metastasizing across the Task Force’s ordered body. Whereas the exterior of the Khowst base might have made it aesthetically appear to be a sprawling, open space behind high HESCO barriers, guard towers, and a well-fortified main entrance, a knowing eye walking the interior would instead recognize it as a series of bases within bases, defined by cipher locks, guarded doors, and thick walls. Protected and maintained behind these features were the tribal narratives of our different teams.

Eventually my efforts to lure the monkey away from the intelligence analysts’ annex worked. She hopped down from the wall and, taking the banana from my hand, perched nimbly on my shoulder. Now reunited, and safe from the intelligence team’s retribution, we headed back to the Task Force’s side of the compound. I had a conference call to dial in to.

“Chris on the line,” I said, after returning to my team’s courtyard, dropping the monkey off in our annex, and joining the call from our team room. My solid-line superior—an operations officer in Bagram, Afghanistan—was leading the discussion, and the topic at hand was a recent raid that we’d been forced to cancel the night prior.

The reason for this cancellation was that a conventional unit had, unbeknownst to us, established a temporary outpost in the same area where our operation’s target was located. We had identified this issue only just before our team had launched, when I’d put in a call to a contact in the conventional unit’s command chain to notify them of our pending mission—an oversight that would have been negated had our teams been better operationally integrated.

Once identified, it was immediately clear that the risk of our forces encountering each other, and the resulting potential for friendly fire, was too high. The conventional team was already established in the area, so we’d decided to stand down. In my mind it had been a successful deconfliction, a sign that the system was working.

“From now on, no more stovepipes,” announced an unexpected voice. It had the unmistakably southern drawl of a senior officer in our bureaucracy who was in command of all the Task Force’s units in Afghanistan. A colonel, he reported directly to McChrystal, who himself was less than a year into his time as the Task Force’s commanding general. It was the first time I’d heard that word—“stovepipe”—used in our organization, but this exchange would be a simple foreshadowing of what was to come.

This tactical slipup was not the type of issue that would normally gain the attention of the colonel overseeing operations around the entire country. But he was, I would understand in hindsight, already involved in deep discussions with McChrystal about the complexity of the fight. He was leveraging this after-action discussion as an opportunity to educate all of us on the direction things would be heading in soon.

Similar discussions were in their early stages across the Task Force. As the colonel spoke about collaboration with other organizations, about early synchronization of efforts versus last-minute deconfliction of actions, and about building truly effective relationships with other organizations, my thoughts drifted to the walls, cipher locks, and security procedures that still separated the various units within the Khowst compound. These were products of, and contributors to, the narrative gulfs that helped keep our organizations compartmentalized.

I realized just how far we had to go. There was no single person who bureaucratically owned this issue, no standalone order that would force us to collaborate. This would be a culture change, something that would take years—but this was a start.

CREATING AN ALIGNING NARRATIVE

The colonel’s words over the phone that day were a product of the Task Force’s still-emerging aligning narrative, which was being developed within the strategic hallways of our organization and would eventually be used to break down the tribal ones of our teams.

I encountered the new narrative just a few weeks after returning from my first deployment with the Task Force. On a morning like any other, I’d gotten to work and logged on to my desktop to check the morning’s e-mail traffic before heading to the gym.

At the top of my inbox was an e-mail marked “high priority,” and the sender was none other than McChrystal. Its contents, sent directly to every member of the organization, were straightforward. In one paragraph a few simple facts were laid out, but more important, they were contextualized in a well considered narrative. Having just returned from deployment, I found that these words had an especially deep significance.

We are at war, and in war, there are winners and losers. We are a force comprised of the most capable, well equipped, and highly trained warriors the battlefield has ever known. Your actions in the fight have shown that this is true.

But make no mistake—we can win every individual battle, and still lose. To win, we will need to change. If you are not willing to become part of that change, then you will not enjoy being part of this organization moving forward.

What we are doing now is not working, and I take responsibility for that. I also take responsibility for the change that lies ahead.

McChrystal’s tone was not threatening, and he did not cast blame. Rather, he offered a simple statement of fact about where we were in the fight and what would start to be expected from our teams if they truly intended to win. More important, it was an invitation to be part of the process, or to leave, with no middle ground offered.

He laid out our overall goal in no uncertain terms, but then, instead of doubling down on our main goal of defeating Al Qaeda or mandating exactly how teams would interact with one another, he went on to remind us generally of the importance of interpersonal interconnection among our teams. Our overarching goal now was not to simply “defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq” but to become the type of culture that could beat a complex enemy. Our process was as important as our end goal, and defining our process was the equation introduced in chapter 1:

Credibility = Proven Competence + Integrity + Relationships

By emphasizing our new priorities to create relationships, to reach across boundaries, and to form the network half of our hybrid model, the equation changed our narrative in one important way. Instead of talking only about winning, we would talk about changing how we operated in order to win. Our alignment triangle would now reflect this change.

Over the next few years, our leadership would leave little room for misinterpretation of what these principles meant or of the necessity of our changing our success-measuring metrics to match them. They would talk to us, day after day, week after week, about becoming something different, something bigger, and something far more capable than we thought possible.

COMMUNICATING AN ALIGNING NARRATIVE

In openly addressing the need for the Task Force’s teams to demonstrate more informal interconnectivity, defy tribal barriers, and eschew reserve in favor of transparency, our leadership began to model a new type of behavior consistent with its still-developing aligning narrative. The implicit hope was that our teams would take this cue and steadily embrace the same behavior among themselves—a trend that would cascade as more and more members of narratively similar peer groups adopted similar behavior, strengthening social pressure on other members to do the same.

For the Task Force, full change would not take hold overnight, but a starting gun had been fired. From that point on, our aligning narrative would be repeatedly, incessantly broadcast into the rank and file of our teams—through e-mail, in-person visits, and daily forums broadcast around the world. Moreover, whenever one of us had a successful operation or result derived from this new type of behavior, our leadership would flag it to the rest of the organization, maximizing the utility of our social learning.

Remember, we started to hear from them, day in and day out, this is always going to be hard. What makes our organization unique is the way we’re trying to communicate, share information, and act as a unified and networked team.

We have the best fighting force in the world. That is not in question. But we need to become networked. We need to connect our teams and partners around the world in order to win. We’re many different teams embarking on a single mission. The way we communicate and share information, the way we protect our relationships with one another, and the way we demonstrate trust—that’s what’s going to release capacity from within our teams.

This narrative, told to us every day, cast each of us as an actor in an entirely new story. We started to feel what was possible, and the best among us were showing a willingness to forgo concepts of “tribe” in order to become part of this new culture.

Every day, our aligning narrative and its associated behaviors became increasingly ingrained in our thinking, a product of the repetition of messages coming from our leadership and of observing the impact that this new approach began to have on the battlefield. Relationships over missions, trust over individual accomplishment; slowly, we all started to believe that this was the approach that would bring us the tangible progress we were all there to achieve.

Attitudes were changing. There was an evolving willingness to make the changes necessary for true alignment. Our horizontal exposure began to inform our new approach to management-by-objectives.

Now we needed to make the practical changes that would allow us to build trust further and extend dotted-line relationships across our solid-line structure. It was time to act upon our aligning narrative.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- How does your organization currently measure horizontal alignment among its teams and functional silos? Would your teams be able to demonstrate horizontal alignment in a non-congressional-hearing-style test setting?

- Your teams might claim to trust and have open lines of dialogue with one another—but can they demonstrate examples of how this trust is helping accomplish your organization’s strategy?

- In your organization’s current state, how would an aligning narrative be best emphasized and contextualized for your teams?