Chapter 6

When the English Were Our Friends: Battling the Indians and the French

In This Chapter

Expanding to the west

Fighting Britain’s war

Squabbling over the fruits of victory

Britain and France were the dominant world powers of the 18th century. They had their religious differences — France was Catholic, Britain was Protestant — but, really, their conflict was a struggle for empire. They spent much of the century fighting each other all over the world, including in North America, where Britain and France both had extensive empires. France’s empire comprised most of present-day Canada, the Upper Midwest, and the West of the present-day United States. The French also controlled New Orleans, along with much of the Mississippi River basin. Britain’s American empire was primarily along the eastern seaboard. The land was divided up into 13 entities that we usually call the 13 colonies.

By and large, France’s American empire was sparsely populated by adventurers, furriers, soldiers, and colonial officials. The French maintained influence by forging alliances with Native American tribes.

Britain’s empire was quite different. From the early 17th century to the middle of the 18th, the population of the 13 colonies grew dramatically because many families put down deep roots in America and flourished over time, creating an identity as Americans. By 1750, those Americans were outgrowing the 13 seaboard colonies and had begun migrating westward into French and Indian territory, sparking conflict.

In this chapter, I explain how tensions grew among everyone who wanted to claim land as their own. I discuss the first phase of the conflict, when the British and American war effort verged on disaster. Then I describe how they turned the tables and achieved victory against the French and Indians, along with the dramatic consequences the victory had for Americans.

American historians call this conflict the French and Indian War. Europeans call it the Seven Years War.

American historians call this conflict the French and Indian War. Europeans call it the Seven Years War.

The First Fur Flies, 1754–1757

The conflict between the Brits and the French all started in the Ohio River Valley, quite close to present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Three rivers — the Allegheny, the Monongahela, and the Ohio — come together at this spot. The Ohio and surrounding river valleys were ideal places to settle, establish farms, and open fur-trading businesses. Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, French Canadians and colonists from Britain’s empire migrated to the area, creating problems.

In 1753, the French built three forts between Lake Erie and the Ohio River to send a not-so-subtle message of French supremacy. Virginia Gov. Robert Dinwiddie and many others in his colony had a lot of money tied up in fur trading in the Ohio River Valley, and French control of that area threatened those investments. In the fall of 1753, Dinwiddie ordered a 21-year-old militia officer, Col. George Washington — yes, that George Washington — to take an expedition, meet with the French, and persuade them to leave.

In 1753, the French built three forts between Lake Erie and the Ohio River to send a not-so-subtle message of French supremacy. Virginia Gov. Robert Dinwiddie and many others in his colony had a lot of money tied up in fur trading in the Ohio River Valley, and French control of that area threatened those investments. In the fall of 1753, Dinwiddie ordered a 21-year-old militia officer, Col. George Washington — yes, that George Washington — to take an expedition, meet with the French, and persuade them to leave.

Washington surrenders

When Washington and a small party of men spoke with the French in the fall of 1753, they received a polite kiss-off. Washington returned to Virginia and reported this to Dinwiddie. The governor decided to escalate the situation. With approval from the British government, he sent Washington back to the Ohio River Valley, this time with a small army and orders to remove the French by force if necessary.

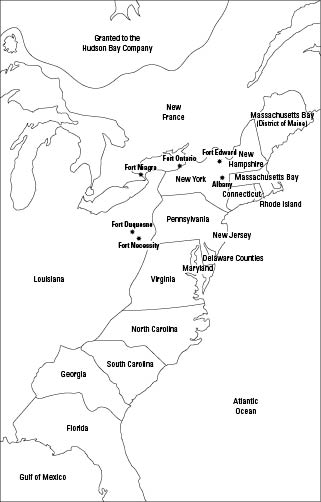

The shooting started on May 28, 1754, when Washington’s men ambushed a mixed group of Canadian and French soldiers, killing 10 and capturing 21 prisoners. Washington didn’t have a large enough force to defeat the French, though. Outgunned and outnumbered, he retreated to the aptly named Fort Necessity. The French surrounded him and forced him to surrender, the only time the proud Virginian would ever do so. Washington’s expedition was the first battle in a seven-year world war between Britain and France. Figure 6-1 shows where battles took place when the French were dominating the French and Indian War.

Figure 6-1: Map of the French and Indian War, 1754–1757.

Braddock’s traditional tactics fail

In the wake of Washington’s disaster, the British government decided on a forceful response. Realizing that they couldn’t rely solely on colonial militiamen to fight the French and their Native American allies, officials in London sent regular British troops under Gen. Edward Braddock to North America. He arrived on February 19, 1755, and spent the next few months building up his supplies, coordinating his efforts with colonial militia commanders, and preparing for the campaign ahead.

When the British and American armies moved west in the summer of 1755, their objective was to sweep away the French forts in all the disputed areas, an ambitious task. Braddock led the main effort against Fort Duquesne, a newly built French rampart located at the site of present-day Pittsburgh.

Braddock’s troops crossed the Monongahela River, a day’s march away from Duquesne. Here, almost in sight of the enemy, he continued to march his army in a classic European linear formation. This maintained cohesion among his soldiers and allowed him to supply his forces well, but considering the rough terrain his troops were negotiating and his enemies’ tactics, Braddock made a poor decision. He would have been better served to spread his troops out, scout Fort Duquesne, and then attempt to surround it.

Braddock’s troops crossed the Monongahela River, a day’s march away from Duquesne. Here, almost in sight of the enemy, he continued to march his army in a classic European linear formation. This maintained cohesion among his soldiers and allowed him to supply his forces well, but considering the rough terrain his troops were negotiating and his enemies’ tactics, Braddock made a poor decision. He would have been better served to spread his troops out, scout Fort Duquesne, and then attempt to surround it.

Instead, on July 9, 1755, the French and Indians ambushed Braddock’s soldiers as they walked, in a predictable straight line, down a trail. The French and Indian force of 600 men was hidden by dense foliage on either side of the trail. They shot musket fire into the red-coated British soldiers who couldn’t see their enemies. Up and down the line, musket balls smashed into men, provoking screams of pain. The British fired back in confused volleys. Panic set in as men ran for safety, bumped into one another, and got hit by enemy fire. Braddock courageously ran around everywhere, rallying his men, braving the enemy fire, but it was no use. In a matter of three hours, the enemy inflicted 877 casualties, including 456 killed, on the British and drove them back across the river. Braddock himself got shot in the lung and died four days later with the full knowledge that he had suffered a catastrophic defeat.

Instead, on July 9, 1755, the French and Indians ambushed Braddock’s soldiers as they walked, in a predictable straight line, down a trail. The French and Indian force of 600 men was hidden by dense foliage on either side of the trail. They shot musket fire into the red-coated British soldiers who couldn’t see their enemies. Up and down the line, musket balls smashed into men, provoking screams of pain. The British fired back in confused volleys. Panic set in as men ran for safety, bumped into one another, and got hit by enemy fire. Braddock courageously ran around everywhere, rallying his men, braving the enemy fire, but it was no use. In a matter of three hours, the enemy inflicted 877 casualties, including 456 killed, on the British and drove them back across the river. Braddock himself got shot in the lung and died four days later with the full knowledge that he had suffered a catastrophic defeat.

George Washington was in Braddock’s ill-fated battle. The tall Virginian earned a reputation for being cool under fire. Some participants believed that, without Washington’s brave leadership, the entire force would have been killed.

George Washington was in Braddock’s ill-fated battle. The tall Virginian earned a reputation for being cool under fire. Some participants believed that, without Washington’s brave leadership, the entire force would have been killed.

Montcalm marches on

The French now had the initiative. Their commander was Gen. Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm. In the summer of 1756, he led a combined army of French soldiers and Canadian militiamen into New York and captured Fort Oswego, an important British outpost located near present-day Syracuse. With Oswego in French hands, the British colonies lost their access to rich fishing and trading routes on the Great Lakes.

The next year, Montcalm besieged Fort William Henry on Lake George near present-day Glen Falls, New York. By now, Montcalm’s army had swelled to a force of about 8,000 regulars, Canadians, and Native Americans. They outnumbered the British and American colonists by almost four-to-one. The British commander, Lt. Col. George Monro, resisted stubbornly. But in August, when he learned no reinforcements could reach him, he knew he must surrender. With much chivalry, he and Montcalm negotiated a gentleman’s capitulation (that is, a surrender with conditions attached). Amid great pomp and ceremony, the British and Americans turned the fort over to the French. Thus honorably paroled, Monro’s troops began a march toward another British fort.

Montcalm’s control over his Native American allies was tenuous at best. To the Indians, the European-style ceremony didn’t constitute an honorable end to hostilities. So the Indians pursued Monro’s column and, against Montcalm’s express wishes, attacked. In the ensuing melee, the Native American fighters killed about 300 people, scalping many of their victims, whether dead or alive. The 2,000 survivors scattered all over the upper New York wilderness, eliminating Monro’s army as any kind of effective military organization.

Some Indian tribes put enormous pressure on their fighters to bring home scalps as war trophies. Such was the case for many of Montcalm’s allies at Fort William Henry. After the ambush, they were so eager to retrieve scalps that they even dug up corpses to get them. These Indians had no idea that some of the corpses were teeming with smallpox. The infected scalps spread great disease and death in those tribes.

Some Indian tribes put enormous pressure on their fighters to bring home scalps as war trophies. Such was the case for many of Montcalm’s allies at Fort William Henry. After the ambush, they were so eager to retrieve scalps that they even dug up corpses to get them. These Indians had no idea that some of the corpses were teeming with smallpox. The infected scalps spread great disease and death in those tribes.

Even as Montcalm’s campaigns were unfolding, pro-French Native American tribes launched devastating raids into Pennsylvania, Virginia, and across upstate New York. The Indians crushed colonial farms and villages, burning, scalping, plundering, and generally leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. Needless to say, these raids sent the 13 colonies into a veritable panic. The average American was now deeply worried about the encroaching power of Catholic France and its Native American friends.

The Brits Regroup, 1758–1763

In 1757, with the British war effort in real crisis, William Pitt ascended to the position of secretary of state of Britain, which gave him control over the country’s war policies. For more than a generation, the country’s leaders had been arguing the merits of two major strategies:

Continental: This group argued that the best way to defeat France and advance British interests was to send large numbers of troops to the European continent.

Maritime and colonial: These men advocated the use of superior British naval power to defeat the French at sea and, on land, fight in colonial areas around the globe.

Pitt was definitely an advocate of the maritime and colonial strategy. He believed that North America was the decisive theater in the war with the French, and he was determined to win there at all costs.

Upon taking office, Pitt implemented three new policies that turned the war in Britain’s favor:

He ordered the Royal Navy to blockade French ports. This cut France off from its North American colonies. Montcalm, for instance, could not be reinforced well enough to follow up on his victories. He was forced to go on the defensive.

With control of the seas, Pitt shipped more British soldiers to America to carry out a new offensive.

He paid for the arming, equipping, and training of colonial militia. This netted him 42,000 recruits in 1758 and 1759. Pitt’s commanders often used these Americans as support troops, freeing up the better-trained British regulars to fight.

Going on the offensive

As Pitt’s policies gradually bore fruit, the initiative for offensive operations passed from the French to the British. From 1758 through 1760, the British and their American colonial allies unleashed a series of offensives designed to push the French back from their frontier forts and then take Canada from them. Figure 6-2 shows the battles in the second phase of the French and Indian War.

Figure 6-2: Map of the French and Indian War, 1758–1760.

Louisbourg

The first major British move was at the Fortress of Louisbourg, a French stronghold located in present-day Nova Scotia. In the summer of 1758, a British army numbering some 13,000 soldiers invaded the area and besieged Louisbourg. The siege lasted from June 19 through July 26. For that five-week period, British cannons and ships pounded the fort and sunk several French ships. Finally, the French could take no more and surrendered.

Unlike the year before when Montcalm had afforded Monro all honors of war at Fort William Henry, the British commander, Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, refused to extend the same courtesy to the Louisbourg garrison. He ordered the French to turn in all their arms, equipment, and colors because he didn’t want to fight the same units somewhere else. The French were not pleased, but they complied. However, the soldiers of the Cambis Regiment destroyed their muskets and burned their colors rather than hand them over to the victorious British.

Fort Duquesne

A British force under Gen. John Forbes built a road across Pennsylvania in 1758, with the goal to win back Fort Duquesne. Forbes had 6,000 men, including 2,000 Virginia and Pennsylvania militiamen. Once again, George Washington was on hand.

The British were in a better strategic position now than three years before during Braddock’s expedition. In 1755, they had consummated an agreement called the Treaty of Easton with the Shawnee and Delaware Indian tribes, former allies of the French. In return for abandoning that alliance, the British promised the Indians a trading post, with no British military presence, at the site of Fort Duquesne. The removal of the Shawnees and Delawares from the war crippled the French in the Ohio River Valley.

The British were in a better strategic position now than three years before during Braddock’s expedition. In 1755, they had consummated an agreement called the Treaty of Easton with the Shawnee and Delaware Indian tribes, former allies of the French. In return for abandoning that alliance, the British promised the Indians a trading post, with no British military presence, at the site of Fort Duquesne. The removal of the Shawnees and Delawares from the war crippled the French in the Ohio River Valley.

When the British neared Fort Duquesne, their leading elements fought a desperate battle with French regulars. In this fight, 100 Pennsylvanians ran away, while the Virginians, with Washington among them, fought well. The French won the battle, though. In so doing, they captured several dozen men from a Scottish regiment. The French decapitated many of the Scotsmen, mounted their bloody heads on stakes, and draped their kilts around the stakes. This shocking incident, along with Amherst’s refusal to afford full military honors to his French prisoners at Louisbourg, indicated that the war was becoming steadily more vicious.

Forbes reorganized his men for another push on Duquesne. He expected a serious fight, but instead, the French, knowing they were badly outnumbered, burned the fort and left. In violation of the Treaty of Easton, the British promptly built a new fort and named it Fort Pitt, after William Pitt.

Fort Pitt was situated right at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers. As you may guess, the Delawares and Shawnees were not pleased that the British reneged on their agreement to hand over this vital ground. The Indians besieged the fort in 1763 but never took it. Eventually, in the years leading up to the Revolution, the British abandoned the fort and the Americans took control of it. From this spot, the city of Pittsburgh came into existence. All that remains of the fort today is a house and some of the fort’s foundations, all located at Point Park, in downtown Pittsburgh.

Fort Pitt was situated right at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers. As you may guess, the Delawares and Shawnees were not pleased that the British reneged on their agreement to hand over this vital ground. The Indians besieged the fort in 1763 but never took it. Eventually, in the years leading up to the Revolution, the British abandoned the fort and the Americans took control of it. From this spot, the city of Pittsburgh came into existence. All that remains of the fort today is a house and some of the fort’s foundations, all located at Point Park, in downtown Pittsburgh.

Quebec and beyond

By 1759, the British were succeeding everywhere in North America. They had pushed the French out of the Ohio River Valley and much of upper New York. The British and American colonials were now in a position to invade Canada, the heart of the French empire in North America.

Using Louisbourg as a jumping-off point, a Royal Navy fleet of about 200 ships carried 7,030 British regular and 1,300 American militiamen up the St. Lawrence River to Quebec. Montcalm was defending the city with about 14,000 French regulars and Canadians. Throughout the summer of 1759, the Royal Navy sailed up and down the waters around Quebec, looking for a good spot to land the troops. Several times the British landed troops, only to be rebuffed by the French, who seemingly had every approach heavily defended.

Out of desperation more than innovation, the British ground commander, Gen. James Wolfe, on September 10, 1759, ordered an elite force to land at the base of some steep cliffs, two miles from Quebec. Wolfe figured that Montcalm would never expect him to land in such a rough spot, and he was correct. Wolfe’s troops climbed hand over hand up the cliffs and overwhelmed a surprised Canadian garrison.

This success was just the opening Wolfe had been waiting for all summer. He quickly reinforced his assault troops with 4,500 redcoats. They clashed with the French in a European-style battle on the Plains of Abraham. In a matter of hours, the British routed the French, sending them into full retreat back into the walled city of Quebec. This was the equivalent of checkmate in a game of chess. Cut off from resupply, outnumbered, and outgunned, the French had little choice but to surrender Quebec on September 18, 1759. The next spring, the French attempted, but failed, to recapture Quebec.

The battle at the Plains of Abraham claimed the lives of both commanders. Several musket balls tore through Wolfe. He bled to death, all the while watching the French retreat. Meanwhile, Montcalm also got hit during the retreat. He staggered into Quebec. Seeing the concerned expressions on his men’s faces, he assured them he was all right. He wasn’t. He died within a day.

The battle at the Plains of Abraham claimed the lives of both commanders. Several musket balls tore through Wolfe. He bled to death, all the while watching the French retreat. Meanwhile, Montcalm also got hit during the retreat. He staggered into Quebec. Seeing the concerned expressions on his men’s faces, he assured them he was all right. He wasn’t. He died within a day.

The French surrender

For the British, the capture of Quebec meant that they now controlled the St. Lawrence River and could move around Canada at will. In September 1760, they surrounded the last remaining French forces at Montreal. The French governor, Pierre François de Rigaud, surrendered the city and all of Canada to the British. The fighting in North America was finally over.

The British conquest of the Ohio River Valley and Canada was a momentous event for the future of North America. British influence in such places as western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan eventually led rebellious American settlers to claim those lands for themselves after they created their new nation. Control of Canada gave Britain a near-permanent presence in North America, even after the American Revolution. Also, when Britain conquered Canada, it guaranteed a divided ethnic makeup of that country between Anglos and French. Naturally, the conquered French resented — even despised — their Anglo countrymen. Even today, French-speaking Canadians (often called Québécois) chafe at their association with much of the rest of the country, which traces its heritage, institutions, and customs to Britain.

The British conquest of the Ohio River Valley and Canada was a momentous event for the future of North America. British influence in such places as western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan eventually led rebellious American settlers to claim those lands for themselves after they created their new nation. Control of Canada gave Britain a near-permanent presence in North America, even after the American Revolution. Also, when Britain conquered Canada, it guaranteed a divided ethnic makeup of that country between Anglos and French. Naturally, the conquered French resented — even despised — their Anglo countrymen. Even today, French-speaking Canadians (often called Québécois) chafe at their association with much of the rest of the country, which traces its heritage, institutions, and customs to Britain.

The war officially ended on February 10, 1763, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. In this agreement, France ceded Canada and all of France’s North American empire east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. Secretary of State Pitt and the British crown had won a huge victory.

What the War Meant to Americans

In one sense, the French and Indian War was the key event of the 18th century in America because it led to the Revolution (see Chapter 7). While the French and Indian War raged, Americans were concerned with the erosion of their rights by the imperial power of France. With the war over, the French enemy defeated, and the British empire dominant in North America, Americans increasingly came to view British imperial power as the main threat to liberty.

Security and growing independence

The defeat of France guaranteed that the 13 colonies would survive. After 1763, none of Britain’s imperial rivals even dreamed of infringing on those colonies. This newfound security meant that the American colonists were less and less dependent upon Britain for protection, weakening the ties between colony and home country.

Expansion beyond the Appalachians

To the Americans, the war had partially been about removing the French from the Ohio River Valley. So at the conclusion of hostilities, eager American colonists began crossing the Appalachian Mountains, pouring into the valley. Often they set up homes on land that the British had promised to Native American tribes in return for their assistance during the war. Not surprisingly, this created real problems.

Various Indian tribes attacked frontier posts as far west as Detroit and as far east as Pennsylvania. The British couldn’t allow this chaotic situation to continue. Between 1763 and 1765, they squelched Indian resistance in a series of campaigns. Then they set about curbing American expansion.

Unwelcome supervision from London

In 1763, Britain’s head of state, King George III, issued the Proclamation Act. The act decreed that no Americans could migrate west of the Appalachian Mountains. The king declared that this land belonged to the Native Americans who had stood with England during the war. Moreover, he ordered his soldiers to forcibly remove American settlers from Indian land.

The colonists viewed this as a betrayal. Some of them had fought in the war, and they believed that land was their just reward. Whenever they could, they simply ignored the king’s decree and moved wherever they wanted. The result was conflict with Indians and British regulars, the latter of whom the Americans now began to view as sinister imperial overseers.

Britain won the war, but she was deeply in debt, to the tune of well over £100 million. The need to recoup that debt, more than anything else, led the British government to govern America with more direct supervision than ever before.

Britain won the war, but she was deeply in debt, to the tune of well over £100 million. The need to recoup that debt, more than anything else, led the British government to govern America with more direct supervision than ever before.

The British felt that, to a great extent, they had fought the war to protect the American colonists. With the common enemy defeated, the British then deemed it reasonable that the Americans should pay their fair share of the cost of victory. In the 1760s, the London government implemented a new series of taxes, all of them designed to eat away at the debt.

The Americans were outraged. For more than 100 years they had enjoyed virtual autonomy in their everyday lives. They had seldom, if ever, paid these kinds of direct taxes to London. Many Americans didn’t think the British government had the right to arbitrarily impose these taxes, much less restrict the movement of settlers (see the previous section). The stage was now set for a major showdown between the colonials and their ostensible mother country.