Chapter 8

War and Peace: Battling Indians, Old Friends, Tax Delinquents, and Pirates

In This Chapter

Expanding westward

Establishing the power to tax

Protecting commerce abroad

Americans may have won their independence from Great Britain, but that hardly guaranteed them security. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a dizzying array of internal and external adversaries threatened the viability of the new United States. Native American tribes stood squarely in the path of a country that aspired to expand its borders far to the west. Bitter arguments flared among Americans as to how the new nation should govern itself. Should the United States have a strong central government, with extensive powers to tax and a standing military force, or would such a powerful government threaten the hard-won liberties Americans so cherished?

European imperial empires such as Britain and France still wielded enormous power in North America, as well as on the world’s oceans, threatening the United States’ security. To top it all off, North African city-states used organized piracy to extract wealth from international shipping routes in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, calling into question whether the United States could even protect its own ships. It all made for a dangerous, uncertain world.

In this chapter, I discuss the problems the new United States had with Native American tribes in what became known as the Old Northwest. I describe the difficulties the infant republic experienced in collecting taxes from its own citizens, as well as its run-ins with imperial Europe and adversarial Muslim kingdoms on the North African coast.

New Americans versus Native Americans

Nearly every American expected the new United States to expand westward. In fact, Americans had already spread into Kentucky and Tennessee during the Revolutionary War. In the Treaty of Paris, the agreement that ended the Revolutionary War, Britain turned over its American lands east of the Mississippi River to the U.S. In the late 18th century, Americans referred to this area, which comprised much of present-day Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio, as the Old Northwest (see Figure 8-1). In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, formally opening up this territory for American settlement.

Figure 8-1: Map of the Old Northwest.

Rising tension with Indian tribes

Numerous Native American tribes populated the Old Northwest. Most of them had alliances with the British, and some had even fought on their side during the war. What’s more, in spite of what the British had agreed to in the Treaty of Paris, British troops remained in many of their forts and urged their Native American allies to resist U.S. encroachment. The stage was set for conflict.

Throughout the 1780s, American settlers poured across the Ohio River into the Old Northwest. Some of them made homes on sparsely populated land. Others migrated onto Indian land, causing immediate problems. Tension, strife, and bloodshed soon followed. The American government sought to deal with this crisis diplomatically by negotiating treaties with the Indians, but this failed.

A confederation of tribes that included the Shawnees, Miamis, Lenapes, and Ottawas banded together to stop American expansion. This tribal confederation insisted that the boundary line between the United States and themselves must be the Ohio River. The Americans would not accept this. By 1790, the area was in a state of constant warfare and westerners were pleading with their young government for help.

Little battles with big consequences

In June 1790, the federal government responded by sending a mixed force of regular Army soldiers and militiamen to attack the Indians. The Native Americans ambushed them and defeated them. When the government sent yet another militia-dominated column of soldiers, the Indians pinned the column against the Wabash River and inflicted 900 casualties on them.

In the wake of these sobering defeats, George Washington, who was serving as the country’s first president, decided to build a truly competent military force. Ever since the Revolution, Americans had been arguing about the need for a professional army. Some thought such armies were instruments of oppression and dictatorship, not to mention ruinously expensive. They believed that a militia (an army of citizen soldiers called to fight in times of emergency) could best handle American security. Others, like Washington, believed that a professional army, under proper civilian authority, was an absolute necessity for the republic’s survival.

Washington resumed negotiations with the tribal confederation, but he expected that little would come from such talk. So he persuaded Congress to raise a trained army of 5,000 soldiers to fight the tribal confederation. He chose an excellent commander, Gen. Anthony Wayne, to preside over this force. For two years, Wayne trained his men hard, preparing them well for war.

Washington resumed negotiations with the tribal confederation, but he expected that little would come from such talk. So he persuaded Congress to raise a trained army of 5,000 soldiers to fight the tribal confederation. He chose an excellent commander, Gen. Anthony Wayne, to preside over this force. For two years, Wayne trained his men hard, preparing them well for war.

In September 1793, with the Indians still insisting on the Ohio River boundary, Washington ordered Wayne to resume hostilities. In less than a year, Gen. Wayne’s disciplined army inflicted a series of devastating defeats on the Native Americans. The tribal confederation turned, in vain, to the British for help. With a world full of obligations, the British were disengaging from the Old Northwest, leaving the confederation vulnerable. This, in combination with Wayne’s triumphs, finished off the tribal confederation. The Indians agreed to the Treaty of Greenville, which ceded all of Ohio to the United States. In the years to come, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan would all eventually come under U.S. control.

New Americans versus the Government

When the 13 colonies defeated Britain in the Revolutionary War, they loosely organized themselves under a new government called the Articles of Confederation. Under the Articles, Congress was the highest power in the land. Every state was represented equally in Congress, and the central government was weak, with little power to tax, make war, or regulate trade. Because most Americans believed that strong central authority threatened individual liberty, they initially liked the idea of a weak American government.

The trouble was that this weak government couldn’t police the frontier, provide security, negotiate with foreign powers, or establish any sort of coherent interstate economic policy. The resulting chaos awakened a major debate between nationalists who advocated a stronger central government and anti-nationalists who liked things as they were. All of this played out in several tax-collecting crises that had military implications.

The trouble was that this weak government couldn’t police the frontier, provide security, negotiate with foreign powers, or establish any sort of coherent interstate economic policy. The resulting chaos awakened a major debate between nationalists who advocated a stronger central government and anti-nationalists who liked things as they were. All of this played out in several tax-collecting crises that had military implications.

Shays says nay to taxes

One legacy of the Revolution was financial debt. Congress and every state had incurred serious debt during the war years. Just as Britain had sought to recoup war debts by taxing colonists in the 1760s (see Chapter 7), so too state governments in the new American nation taxed their citizens in the 1780s. In Massachusetts, the burden of taxation fell heavily upon farmers in the western part of the state. Many of these farmers were patriot veterans of the war who had not received the land and pensions that Congress had promised them. The farmers believed that the taxation was so great that they would lose their homes and property.

In 1786, a group of these farmers, led by a former Continental Army captain named Daniel Shays, rebelled against the state government. The rebels called themselves Regulators. Their rebellion took the shape of a series of demonstrations in Springfield, Massachusetts, and a few other towns. Congress had no power to do anything about the Regulators. Ultimately, the state of Massachusetts had to hire a mercenary militia, under the command of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, to disperse the rebellion, fortunately with very little violence. Most of the Regulators eventually left Massachusetts or were pardoned by the state authorities.

Shays’s Rebellion led many Americans, including prominent leaders like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Washington, to question the long-term viability of the Articles of Confederation government. This concern, in turn, led many leaders to consider establishing a stronger central government. The ultimate result of all of this was the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in which delegates abolished the Articles in favor of a strong central government and the Constitution under which we live today.

Shays’s Rebellion led many Americans, including prominent leaders like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Washington, to question the long-term viability of the Articles of Confederation government. This concern, in turn, led many leaders to consider establishing a stronger central government. The ultimate result of all of this was the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in which delegates abolished the Articles in favor of a strong central government and the Constitution under which we live today.

The Whiskey Rebellion

As president, Washington chose Alexander Hamilton to be his secretary of the treasury. Hamilton had served under Washington during the war, and the two had a father-son type of relationship. In addition to being a lawyer, Hamilton possessed a keen mind for finances. He devised an elaborate plan to phase out the serious wartime debt that was eating away at the federal treasury. A key aspect of the plan was a tax on whiskey passed in 1791.

Western farmers who distilled their own liquor were particularly hard hit by Hamilton’s whiskey tax. Not only were they taxed at a higher rate than large distillers, they didn’t have much cash in the first place because they lived in remote areas. This was especially true for western Pennsylvanians and farmers who lived in the Appalachian Mountains.

Western farmers who distilled their own liquor were particularly hard hit by Hamilton’s whiskey tax. Not only were they taxed at a higher rate than large distillers, they didn’t have much cash in the first place because they lived in remote areas. This was especially true for western Pennsylvanians and farmers who lived in the Appalachian Mountains.

Needless to say, these moonshine-making folks didn’t react well to the new tax. They believed that the federal tax was just as unjust as Britain’s attempts at taxation in the 1760s and 1770s (see Chapter 7). So, just as in those years, they refused to pay. The farmers also engaged in bitter protests and outright rebellion. They assaulted tax collectors. In one instance, a mob caught a collector, cropped his hair, covered him in tar and feathers, and even took his horse.

President Washington was deeply disturbed by this Whiskey Rebellion. He thought it was similar to Shays’s Rebellion a few years earlier (see the “Shays says nay to taxes” section earlier in this chapter). Remembering how ineffective the Articles of Confederation government had been during that crisis, Washington was determined to demonstrate federal authority to collect taxes and keep order. He amassed a militia army of 13,000 troops for an expedition to western Pennsylvania. He even rode with them himself. This overwhelming force crushed the rebellion quickly and bloodlessly. Washington pardoned most of the perpetrators.

The Whiskey Rebellion set a precedent. It demonstrated the new constitutional government’s willingness and ability to use military force to keep law and order. If an American didn’t like a law and wanted to change it, he had to do so through peaceful, constitutional means.

The Whiskey Rebellion set a precedent. It demonstrated the new constitutional government’s willingness and ability to use military force to keep law and order. If an American didn’t like a law and wanted to change it, he had to do so through peaceful, constitutional means.

In spite of the federal government’s Whiskey Rebellion victory, Congress eventually repealed Hamilton’s whiskey tax in 1803. The government never raised much money from the tax anyway.

In spite of the federal government’s Whiskey Rebellion victory, Congress eventually repealed Hamilton’s whiskey tax in 1803. The government never raised much money from the tax anyway.

New Americans versus French “Friends”

In the 1790s, France and Britain were once again at war with each other. France had undergone a revolution that saw the overthrow of the king, the establishment of a republic, and the onset of a war with much of the rest of Europe. Of course, France’s main enemy, as usual, was Britain. The two nations were locked in a bitter struggle for control of the Atlantic.

President Washington sought neutrality for the U.S., but this was easier said than done. Overseas trade, particularly with Europe, was a vital part of the American economy. If we traded with the British, the French were angry. If we traded with the French, the British were upset. Even the American people were divided on which side to support. Those who lived in the Northeast and the coastal areas favored Britain because of their commercial ties to the old mother country. Americans in the West and the South preferred France because, in their view, Britain was still the main threat on the frontier. Plus, France was an old ally from revolutionary times.

In 1794, the Washington administration signed a commercial trading agreement with Britain. The French viewed the agreement as equivalent to an alliance with their enemy. French ships began attacking and seizing any American ships that did business with England. The French then cut off diplomatic ties with the U.S., saying they would only restore relations if the Americans paid them a handsome bribe.

All of this inflamed anti-French sentiment in America. A new president, John Adams of Massachusetts, unveiled ambitious plans to build a large navy and army to fight France. Although the two countries never formally declared war on each other, fighting at sea went on from 1796 until 1800 when Napoleon Bonaparte, the French emperor, defused the tension and restored normal diplomatic relations with the U.S. This episode is generally known as the Quasi-War with France.

When Washington retired in 1796, he urged his countrymen to “avoid the broils of Europe.” But the Quasi-War showed that the United States could easily be drawn into European wars, even if Americans sought to remain neutral. The same issue would arise many more times in the future.

When Washington retired in 1796, he urged his countrymen to “avoid the broils of Europe.” But the Quasi-War showed that the United States could easily be drawn into European wars, even if Americans sought to remain neutral. The same issue would arise many more times in the future.

Pirates of the Mediterranean

In 1800, Thomas Jefferson was elected president of the United States. As a Democratic-Republican, he was deeply suspicious of a regular military establishment. He worried that professional officers might turn into a new aristocracy (a privileged ruling class). So, too, professional soldiers could threaten or coerce the people, depriving of them of their inalienable human rights.

When Jefferson became president, he initially cut back on the armed forces. For maritime security, he felt that America could be protected by a fleet of small coastal gunboats. He sold off or decommissioned most of the Navy’s conventional warships.

Pirate pasha demands payment

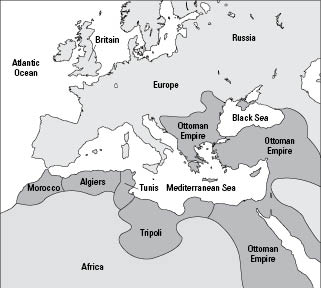

In the late 18th century, the Barbary states of North Africa (see Figure 8-2) often captured international ships sailing off their coasts. In return for safe passage through the Mediterranean Sea, they demanded payment from the ship’s crews or their government. The Barbary states included Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. European powers like Great Britain took advantage of this situation by paying the Barbary states to capture their enemies’ ships.

Figure 8-2: Map of the North African coast in the early 1800s.

American ships sailed these waters quite often. Throughout the last two decades of the 18th century, the American government negotiated treaties with the Barbary states in return for protection of American commerce. These protection treaties only went so far. Sometimes Barbary pirates seized American ships and held the crewmen hostage. The U.S. government didn’t always pay the North African rulers as they had pledged in the protection treaties. The result was conflict.

In 1801, Pasha Yusuf Qaramanli, the ruler of Tripoli, demanded payment, or tribute, from the American government for the use of his waters. He felt that the Americans had incurred years of debt without paying. To punish the American debtors, he pledged to make war on American ships off the Tripolitan coast.

Jefferson sends in a coalition navy

When the crisis arose with the pasha, Jefferson had only a small navy on hand. Even so, he had no intention of caving in to the pasha, a man he thought of as little more than a glorified robber. Jefferson sent his small navy to the Mediterranean with instructions to coordinate its efforts with a likeminded coalition of ships from Sweden, Sicily, Malta, Portugal, and Morocco. This worked well. The pasha backed off of his demands.

When the crisis arose with the pasha, Jefferson had only a small navy on hand. Even so, he had no intention of caving in to the pasha, a man he thought of as little more than a glorified robber. Jefferson sent his small navy to the Mediterranean with instructions to coordinate its efforts with a likeminded coalition of ships from Sweden, Sicily, Malta, Portugal, and Morocco. This worked well. The pasha backed off of his demands.

From 1801 to 1803, this small force of American ships, with one frigate and a few supporting ships, sailed the waters off Tripoli. But in October 1803, the frigate USS Philadelphia ran aground on the North African coast. The pasha captured the crew of 300 sailors and prepared to ransom them, their ship, and its cargo. A few months later, in February 1804, Lt. Stephen Decatur raided Tripoli harbor with a small group, burning Philadelphia. The pasha no longer had the ship to bargain with. In the meantime, the surviving American ships routinely bombarded the harbor.

An intriguing victory in Tripoli

The situation burned with intrigue. William Eaton, the American consul to Tunis, was hatching plans with the pasha’s brother to overthrow him. They compiled a force of Arabs, Greeks, and U.S. Marines (hence the line “to the shores of Tripoli” in the Marines’ Hymn).

Before Eaton’s makeshift force had the chance to get rid of the pasha, the Tripolitan ruler and Jefferson struck a deal. Jefferson agreed to pay a ransom for the return of the Philadelphia’s crew. In exchange, the pasha agreed not to mess with American ships.

Jefferson reaped a nice political windfall from this Mediterranean episode. The country buzzed with poems, books, paintings, and statues commemorating the supposedly great victory over the pasha. However, Jefferson was quite fortunate to have encountered a weak enemy in Tripoli. The United States Navy was so small and weak in Jefferson’s time that it would have struggled to defeat an opposing navy of any decent size and training.

If the United States wanted to protect its overseas trade, it would need a formidable navy, not a few gunboats that could barely even cover the American coast.