Chapter 12

The “Indian Wars”: The Army Secures the Frontier

In This Chapter

Overwhelming the western tribes

Policing the frontier

Fighting formidable enemies and restricting their way of life

Between 1862 and 1900, as Americans expanded westward at an ever increasing rate, they clashed with Native American tribes that controlled significant pockets of territory in the West. This was the final phase of a continuous conflict between settlers and Native American tribes that had been going on since the earliest days of European colonization in America. By now, the vast majority of Native American tribes in North America had been killed off by disease, relocated to reservations, or assimilated into the United States.

The western tribes, then, were the last representatives of ancient Indian civilizations that now stood in the way of U.S. expansion. When Americans moved westward, they inevitably conflicted with Native Americans who were defending their traditional homes. Sometimes the result was violence and outright warfare between the U.S. Army and Native American tribes.

In this chapter, I discuss Native American tribes of the West. I explain how and why they clashed with white settlers and a U.S. Army that attempted to enforce government policy while keeping whites and Indians from killing one another. Finally, I describe some of the most important battles the Army fought with Indian tribes.

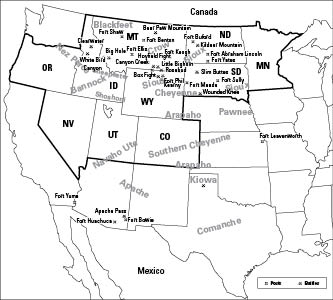

Clashing Cultures

In 1862, at the height of the Civil War, the U.S. Congress passed the Homestead Act. This new law guaranteed 160 acres of western land to any family or individual who agreed to live on it for five years. At the end of that time, the citizen would own the land. The idea was to stimulate expansion in the Trans-Mississippi West, an area of the country encompassing present-day Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Nevada, and Wyoming (see Figure 12-1). By 1900, the Homestead Act had led to the establishment of 372,000 farms in the West.

Figure 12-1: Map of the Trans-Mississippi West, 1860–1890.

The last quarter of the 19th century saw a clash of cultures in the West as the United States expanded in that direction. Native Americans wanted to live on their tribal lands and hang on to traditional, distinctive cultures that often emphasized

Worship of nature

Community ownership of property

Tribal languages, music, art, and village life

Migratory hunting and gathering rather than sedentary agriculture

Primary loyalty to a chief or tribal entity, not a larger country

By contrast, American culture emphasized very different values:

Christianity, which views humanity as the overseer of nature

Capitalism and private property

The importance of the individual

The use and exploitation of natural resources for financial gain

The establishment of stable, permanent farm communities or cities teeming with industrial growth

Nationalistic allegiance to the United States

In the West, the conflict between these two ways of life was inevitable, especially because both cultures were generally quite warlike. The struggle, of course, had been going on ever since Europeans set foot in North America. It continued throughout early American history (see Chapters 6 and 8 for more) as the United States expanded westward. The late-19th-century West was simply the final phase of this long conflict.

In the West, the conflict between these two ways of life was inevitable, especially because both cultures were generally quite warlike. The struggle, of course, had been going on ever since Europeans set foot in North America. It continued throughout early American history (see Chapters 6 and 8 for more) as the United States expanded westward. The late-19th-century West was simply the final phase of this long conflict.

Native American Tribes of the West

As of 1860, myriad Indian tribes populated the West. Some of these tribes were so large that they were known as nations. Most Indians lived simple lives, engaging in farming, hunting, and fishing. Their loyalty was usually to their immediate tribe, not any kind of larger consciousness of being an Indian. Warfare among tribes was common and had gone on for many centuries. In fact, the average Indian often thought of his tribe’s Native American enemies as the main threat to his survival, not white Americans.

But some tribes, or nations, were especially resistant to white encroachment (the taking of Indian land or pressure to sell to the government or settlers). The following sections give you the lowdown on some of the tribes that U.S. settlers and soldiers encountered during the country’s expansion west.

The Sioux

The Sioux nation was among the most formidable of all Indian entities. The Sioux lived in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Nebraska. As whites intruded on their lands, the Sioux pushed west themselves into Montana and Wyoming, displacing the Crows, their bitter enemies. The Sioux were herdsmen, buffalo hunters, and fierce fighters.

The 1990 film Dances with Wolves portrayed Sioux Indians at about the time of the Civil War. In the movie, many real Sioux actors played the parts of their ancestors. Throughout the movie, the actors even spoke a modified version of Lakota Sioux, a prominent language among the Sioux.

The 1990 film Dances with Wolves portrayed Sioux Indians at about the time of the Civil War. In the movie, many real Sioux actors played the parts of their ancestors. Throughout the movie, the actors even spoke a modified version of Lakota Sioux, a prominent language among the Sioux.

The Nez Perce

The Nez Perce tribe at one time controlled about 17 million acres of land that would someday be part of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. They were migratory, constantly moving in pursuit of the buffalo and salmon they relied on to survive.

The Apaches

The Apaches consisted of seven distinct subgroups, each of which spoke its own language. Among them, these tribes dominated much of what would become New Mexico and Arizona. The Apaches were primarily migratory hunters, although they did grow some domesticated plants and were known to trade with other tribes for food. The typical Apache man spent much of his time hunting deer and antelope in the desert Southwest.

The Apaches didn’t fight many big battles. They were masters at mounted guerrilla warfare, and they were among the government’s most famous and the fiercest opponents.

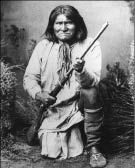

Geronimo, perhaps the most famous Indian chief of all time, was an Apache (see Figure 12-2). He resisted and defied the U.S. government for nearly 25 years until finally surrendering in 1886. After a period of captivity, he became something of a national celebrity, touring the country, appearing at fairs, telling his stories. He died in 1909, but his very name lives on as a symbol of courage and daring.

Figure 12-2: Geronimo was an Apache chief.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

Historians often include the Navajos among the Apache peoples because of their similar language and culture. In World War II, many Navajos served as code talkers. The code talkers were radiomen who transmitted important orders and other military communications in their native language, making them completely unintelligible to mystified Japanese and German eavesdroppers.

Historians often include the Navajos among the Apache peoples because of their similar language and culture. In World War II, many Navajos served as code talkers. The code talkers were radiomen who transmitted important orders and other military communications in their native language, making them completely unintelligible to mystified Japanese and German eavesdroppers.

Expanding Relentlessly Westward

After the Civil War, thousands of American settlers, most of whom were white, migrated to the West. Some of these Americans wanted to escape the crowded cities of the Midwest and Northeast. Some wanted adventure. Some wanted land. Others wanted the independent, healthy lifestyle that the West seemed to offer. Some wanted gold, silver, or other marketable resources. Most wanted wealth of one sort or another. No matter what the motivation for going west, the number of whites soon multiplied dramatically. For instance, in 1866, 2 million whites lived in the West. Twenty-five years later, the white population was 8.5 million.

The average American who went west believed in the concept of Manifest Destiny, a notion that God had given the North American continent to the United States so it could spread its unique culture, liberty, and wealth from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Often, settlers and Native Americans coexisted peacefully, respecting each other’s land and customs. Too frequently, though, whites encroached on Indian land or pressured the Indians for anything of value. At times, unscrupulous Americans stole from the Indians, sold them liquor and weapons, or bilked them out of their land. The Indians sometimes lashed back by massacring settlers or, in less extreme cases, intimidating them in hopes of getting them to leave.

Developing reservations

The U.S. government was of two minds on these simmering troubles. On the one hand, the government wanted to promote westward expansion and add several new states to the Union. On the other hand, the government hoped to protect Native American lands. The result was an Indian reservation system mandated by the federal government. Under this new system, tribes would be confined to clearly definable land known as reservations. In this way, the American government hoped to prevent conflict between Indians and whites, while encouraging westward expansion. As an added benefit, American officials hoped that, under the new policy, Indians would convert to Christianity, settle into farming, and assimilate into mainstream American life.

The U.S. government was of two minds on these simmering troubles. On the one hand, the government wanted to promote westward expansion and add several new states to the Union. On the other hand, the government hoped to protect Native American lands. The result was an Indian reservation system mandated by the federal government. Under this new system, tribes would be confined to clearly definable land known as reservations. In this way, the American government hoped to prevent conflict between Indians and whites, while encouraging westward expansion. As an added benefit, American officials hoped that, under the new policy, Indians would convert to Christianity, settle into farming, and assimilate into mainstream American life.

The reservation policy didn’t solve the problem because it had many flaws:

Native Americans often received the least desirable land that whites didn’t want.

The federal government sometimes forced tribes away from their traditional lands into places that weren’t familiar to them.

Many Indians hated the reservations and left them, rebelling against the government. The Army then had to force compliance, by violence if necessary (see the “Policing with Warfare” section later in this chapter).

White settlers sometimes defied their own government, poaching or even stealing land or resources from Indian reservations.

Consigned to dead-end reservations, Indians had a difficult time assimilating into American life. Most wanted simply to live on their traditional land, in their own culture.

Maintaining security

The Army’s job was to enforce the government reservation policy, a thankless and tricky task. William T. Sherman, the famous Civil War general, summed up the challenge perfectly. “There are two classes of people,” he wrote, “one demanding the utter extinction of the Indians, and the other full of love for their conversion to civilization and Christianity. Unfortunately the army stands between them and gets the cuff from both sides.”

Sherman was right. Some Americans (mainly westerners) favored a harsh policy of annihilation against the Indians. Others (generally in the East) urged benevolence toward the Indians, in hopes of assimilating them into American life. Thus, the government’s reservation policy represented a compromise between these two opposing views. The Army was in the middle, satisfying neither side. Plus, the Army, of course, had the bloody job of fighting Native Americans who defied the U.S. government. This all added up to a dangerous, frustrating experience for soldiers on the frontier.

Policing with Warfare

The term “Indian Wars” is a bit misleading because it calls to mind images of big battles and national mobilization. Actually, the Army fought very few battles of any size or duration in the Old West. More commonly, soldiers endured months and years of mundane duty, usually at dusty, simple military posts. Every now and again, this monotony was broken by the occasional skirmish against defiant Indians who refused to follow government edicts. For the soldiers, then, serving on the frontier was like being part of a police action, rather than a major conflict like the Civil War or World War II. The U.S. won the frontier mainly through attrition, by depriving the Indians of food, water, resources, and comfort, not through combat.

Even so, the Army did, at times, fight significant battles against Native American tribes. The upcoming sections describe some of the most famous such battles.

Paying a stiff price for impulsiveness: Little Bighorn, 1876

In 1868, the U.S. government signed a treaty with the Sioux, requiring them to settle on a large reservation in the Dakotas. The majority of the Sioux complied with the treaty, but powerful groups of dissenters, known as nontreaty Sioux, spurned the agreement. Led by charismatic chiefs such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, they moved west into Montana, in an area bordered by the Powder River. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and many others like them, felt total contempt for whites, whom they considered greedy and untrustworthy. Thus, these proud Sioux were determined to defy the government and live wherever they pleased. For several years, the government ignored their lack of compliance.

Things began to change in 1874, though. Prospectors discovered gold in the Black Hills, on the Sioux reservation. The federal government tried to buy the hills from the Indians, but the nontreaty chiefs torpedoed this plan. In response, the government ordered them to report to the reservation by January 1876 or risk war. Naturally, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and their followers refused. The result was a war fought throughout 1876. The Battle of Little Bighorn, fought on June 25, was the main event of that war.

Army commanders correctly believed that the rebellious Indians were at the Little Bighorn valley (see Figure 12-3). Thinking that the Indians only had a few hundred fighters, the commanders planned to converge on them with three separate columns of soldiers, fight a quick battle, and force the survivors onto the reservation.

Army commanders correctly believed that the rebellious Indians were at the Little Bighorn valley (see Figure 12-3). Thinking that the Indians only had a few hundred fighters, the commanders planned to converge on them with three separate columns of soldiers, fight a quick battle, and force the survivors onto the reservation.

Figure 12-3: Map of the Little Bighorn campaign.

The plan quickly unraveled. On the way to the valley, one column, under Gen. George Crook, fought a costly battle at Rosebud, Montana, in which 28 soldiers were killed and another 56 wounded. These losses and the ferocity of Indian opposition forced him to turn back. Another column, under 7th Cavalry Regiment commander Lt. Col. George Custer, was significantly ahead of the third column, under Col. John Gibbon. The famous Custer was a flamboyant Civil War veteran with flowing, shoulder-length blond hair. On June 25, 1876, he found the main Indian village at Little Bighorn and decided to attack on his own, before Gibbon could arrive. This was a courageous, but impulsive, decision. Custer stirred up a veritable hornet’s nest, because he was outnumbered more than three-to-one. In a frenzied battle, the Sioux overwhelmed Custer, massacring him and 268 of his soldiers. Gibbon’s men made it to Little Bighorn the next day, essentially rescuing the 300 7th Cavalry survivors who had held out all night on a ridge against sporadic Sioux attacks.

Romantically remembered as Custer’s Last Stand, Little Bighorn was, in reality, a disaster for the U.S. Army. But it didn’t lead to victory for the nontreaty Sioux. In the wake of the battle, they celebrated, split up into hunting parties, and acted as if the U.S. government would bother them no more. Instead, the government, stung by the public outcry over Custer’s massacre, poured reinforcements into the area. Eventually, by harassing the Indians and depriving them of their food supply, the Army won this war by 1877. Sitting Bull fled to Canada. Crazy Horse surrendered.

Romantically remembered as Custer’s Last Stand, Little Bighorn was, in reality, a disaster for the U.S. Army. But it didn’t lead to victory for the nontreaty Sioux. In the wake of the battle, they celebrated, split up into hunting parties, and acted as if the U.S. government would bother them no more. Instead, the government, stung by the public outcry over Custer’s massacre, poured reinforcements into the area. Eventually, by harassing the Indians and depriving them of their food supply, the Army won this war by 1877. Sitting Bull fled to Canada. Crazy Horse surrendered.

The Battle of Big Hole, 1877

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, as settlers moved into Nez Perce territory in Idaho and Oregon, the government negotiated treaties restricting the tribe onto an Idaho reservation. As newcomers arrived from back east, they hungered for land and gold at the expense of the Nez Perces. These settlers put intense pressure on the federal government to buy more Indian land, especially from those Nez Perces who had not signed the earlier treaties. In the fall of 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant attempted to do so, but the nontreaty Nez Perce refused to sell. In response, Grant gave them an ultimatum: Sell or be forcibly removed to the reservation in Idaho. Some cooperated; others did not.

The result of all this tension was violence. In the summer of 1877, several hundred rebellious, nontreaty Nez Perces began a march to Montana. They believed that if they could make it into Montana, they could find shelter with the Crow tribe, and perhaps eventually go to Canada or maybe negotiate with Washington for a return to their tribal lands. Along the way, they killed about 20 Idaho settlers and skirmished with U.S. Army soldiers. In late July, Chiefs Joseph, Looking Glass, and White Bird led this band of roving Nez Perces past small units of pursuing soldiers and into Montana’s Bitterroot Valley.

The Nez Perces didn’t fully understand the concept of one nation-state called the United States. They believed that, once they left their white enemies in Idaho and Oregon behind, they would have a clean slate in Montana because, to them, it was a different country. Thus, they didn’t comprehend that Montana, Idaho, and Oregon were all part of the same united country and members of a federal union that bonded all Americans together, no matter where they lived. So when the Indians reached Montana, they were surprised that the Army continued to pursue them.

The Nez Perces didn’t fully understand the concept of one nation-state called the United States. They believed that, once they left their white enemies in Idaho and Oregon behind, they would have a clean slate in Montana because, to them, it was a different country. Thus, they didn’t comprehend that Montana, Idaho, and Oregon were all part of the same united country and members of a federal union that bonded all Americans together, no matter where they lived. So when the Indians reached Montana, they were surprised that the Army continued to pursue them.

In late July, Col. Gibbon mobilized 149 soldiers from his 7th Infantry Regiment, plus 35 Montana volunteers, and tracked down the Nez Perces. On the morning of August 9, 1877, Gibbon found and attacked the Nez Perce encampment at a fork in the Big Hole River, about 10 miles east of the Idaho border.

The Battle of Big Hole raged all day. At first, the soldiers roamed the village, shooting anyone who offered resistance, even women and children. The well-armed Nez Perces fought back quite effectively, shooting several soldiers to death. In a few hours, they drove Gibbon’s forces to a slight rise on the other side of the river from the village. Here, the two sides shot at each other all day. The air was so thick with bullets that dozens of men on both sides were killed or wounded. The bullets shattered bones, knocked out teeth, pierced internal organs, or simply left bleeding flesh wounds. As the hot day wore on, the soldiers suffered from hunger and thirst. Having pinned down the troops, most of the Nez Perces used the cover of nightfall to escape, continuing their exodus.

The Battle of Big Hole raged all day. At first, the soldiers roamed the village, shooting anyone who offered resistance, even women and children. The well-armed Nez Perces fought back quite effectively, shooting several soldiers to death. In a few hours, they drove Gibbon’s forces to a slight rise on the other side of the river from the village. Here, the two sides shot at each other all day. The air was so thick with bullets that dozens of men on both sides were killed or wounded. The bullets shattered bones, knocked out teeth, pierced internal organs, or simply left bleeding flesh wounds. As the hot day wore on, the soldiers suffered from hunger and thirst. Having pinned down the troops, most of the Nez Perces used the cover of nightfall to escape, continuing their exodus.

The Battle of Big Hole cost the lives of 25 soldiers, 6 Montana volunteers, and probably about 80 Nez Perces. In the aftermath of this terrible fight, the Army eventually apprehended the Nez Perces and took them into captivity. Most never returned to their traditional land. A heartbroken Chief Joseph allegedly told his fellow chiefs, “I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

The end at Wounded Knee, 1890

Many other Native Americans shared Chief Joseph’s war weariness. By the 1880s, pitched battles (conventional fights like Little Big Horn and Big Hole) were even more rare than before. The Army wore down any rebellious Native American tribes through sheer attrition. In a larger sense, the expanding American nation did the same thing to any tribes that contemplated defying the government’s policies. By 1890, most every tribe was on its assigned reservation, resigned to an unhappy fate.

The lone exception was a group of Sioux, known as the Lakota. Trapped on a South Dakota reservation, forced to convert from a hunting lifestyle to farming, they were living dead-end lives. To accommodate new white settlers, the federal government siphoned off Lakota territory, in so doing, reneging on an earlier treaty. The Lakota Sioux was part of the group that had slaughtered Custer in 1876, so they had a long history of conflict with the government.

Simmering with anger and nostalgia, the Lakotas frequently engaged in the ghost dance, a ritual that had warlike connotations. The ghost dance was the brainchild of an influential Sioux religious leader who preached that whites would be banished from the earth, while Lakota Sioux, if wearing certain garments, would be impervious to bullets. The meaning behind the Lakotas’ dance caused fear among settlers and soldiers alike.

In response to the growing ghost dance, the 7th Cavalry Regiment surrounded the Lakota Sioux encampment at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. Although the soldiers intended to disarm the Lakotas and take them to Omaha, Nebraska, shooting broke out (accounts still differ as to who fired first). The result was a slaughter in which the troops, with the help of a rapid-firing Gatling gun, killed 300 people, including women and children. The 7th Cavalry lost 25 men killed, mostly by their own crossfire. This sickening massacre ended any remaining Indian resistance to the United States, so most historians see it as the end of the Indian Wars.

In response to the growing ghost dance, the 7th Cavalry Regiment surrounded the Lakota Sioux encampment at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. Although the soldiers intended to disarm the Lakotas and take them to Omaha, Nebraska, shooting broke out (accounts still differ as to who fired first). The result was a slaughter in which the troops, with the help of a rapid-firing Gatling gun, killed 300 people, including women and children. The 7th Cavalry lost 25 men killed, mostly by their own crossfire. This sickening massacre ended any remaining Indian resistance to the United States, so most historians see it as the end of the Indian Wars.