Chapter 14

Over There: The First World War

In This Chapter

A European bloodbath

Joining the Allied coalition

Supporting the war effort here at home

Joining the fight

In the early 20th century, European imperial empires dominated most of the world. The premier empires, France, Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia, had spent years colonizing major portions of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. As they did so, they competed for influence, resources, and military supremacy.

This mad scramble for empire fueled tension among the great powers. In hopes of guaranteeing their security, several of them banded together into mutual alliances. Britain, France, and Russia were part of an alliance (eventually called the Allies) designed for mutual protection against an opposing bloc (which came to be known as the Central Powers) led by Germany and Austria-Hungary.

In the summer of 1914, a political assassination in the Balkans ignited the tinderbox of tensions that eventually became a firestorm of war.

The United States initially declared neutrality when the European war broke out. Americans were primarily concerned with their own hemisphere, and they hoped to remain aloof from Europe’s troubles. However, in the early 20th century, the American economy depended on trans-Atlantic trade, especially with the Allied countries. By 1917, German submarine attacks threatened that trade, leading ultimately to war between Germany and the U.S.

In this chapter, I examine the causes of World War I and give you a feel for the war’s terrible nature. I explain how the United States became involved, how the war affected the folks here at home, and also what kind of impact American soldiers had on the outcome of the conflict.

My Alliance Can Beat Up Your Alliance

On June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo, a 19-year-old Serbian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. This murderous act set in motion a series of events that led to World War I.

Austria-Hungary was hoping to expand into the Balkans at the expense of Serbia. Seizing upon the assassination as a pretext for this expansion, Austria-Hungary demanded major concessions from Serbia. Eventually, with Germany’s approval, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. However, Russia had an alliance to protect Serbia, so it declared war on Austria-Hungary. This, in turn, led to war between Germany and Russia. Figure 14-1 shows how European countries were aligned at the beginning of World War I.

Figure 14-1: Map of European alliances during World War I.

Because France had an alliance with Russia, it joined the war against Germany, as did Britain. Through conscription, all the belligerents mobilized mass armies and navies consisting of millions of men. Hostilities began in early August 1914. On one side were Austria-Hungary and Germany; on the other were Serbia, Russia, France, and Britain.

The reasons for war

Most historians blame World War I on Germany, claiming Germany failed to reign in its hawkish Austro-Hungarian ally, while at the same time it wanted to conquer major portions of Europe. Although true, the roots of the war go deeper than that. Here are the four main causes of World War I:

Nationalism: Almost all the belligerents wanted territory they believed was theirs for ethnic and cultural reasons. They also wanted to prove their national greatness.

Imperialism: Decades of competition for colonies had led to an atmosphere of rivalry, distrust, and fear among the great powers.

The arms race: For years, European powers had engaged in a bitter, costly arms race (a focused effort by countries to build more and bigger weapons than their rivals) that fueled tension and ate up huge sums of money. The best example is Germany’s attempt to build a large navy to rival Great Britain’s.

Alliances: The extensive network of alliances among the European powers increased the chances that a small event, like Princip’s assassination of the Austrian monarch, could lead to a general war. And it did.

The strategies for war

When war broke out in the summer of 1914, both sides anticipated a quick, victorious conflict. Their strategies reflected that belief. The French Plan XVII called for an offensive into the Ruhr, the industrial heartland of Germany. Deprived of its industry, the French believed Germany would then surrender under certain conditions. At the same time, the Russians planned a major offensive into East Prussia (a province in eastern Germany).

When war broke out in the summer of 1914, both sides anticipated a quick, victorious conflict. Their strategies reflected that belief. The French Plan XVII called for an offensive into the Ruhr, the industrial heartland of Germany. Deprived of its industry, the French believed Germany would then surrender under certain conditions. At the same time, the Russians planned a major offensive into East Prussia (a province in eastern Germany).

Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, however, was the most ambitious strategy of all. Facing a two-front war, the Germans decided to go for a knockout blow against France. German armies would crash through neutral Belgium and Luxembourg, invade northern France, wheel around Paris, and force France to fold, all before Britain could enter the war in any strength. At that point, Germany intended to turn its full attention east and defeat Russia.

None of the strategists on either side imagined that the war would last years, require mass mobilization in each of the warring countries, and claim 10 million lives.

The exploits of war

By August 1914, the battles had begun, with the Russians attacking in the East and both sides tearing into each other in the West.

Russia and Germany square off at Tannenberg

Imperial Russia was ruled by the tsar, an aristocratic, almost godlike figure to many Russian peasants. The country was backward and plagued with internal political problems, but its army was formidable for its sheer size.

In August 1914, the Russians mobilized their army and attacked East Prussia much faster than the Germans anticipated. This forced the Germans to reinforce their armies in the East, at the expense of the drive into France. Between August 17 and September 2, the Germans destroyed the Russian attack, capturing 95,000 Russians and inflicting 30,000 more enemy casualties. The battle, known as the Battle of Tannenberg, was an overwhelming German victory, but a costly one because it weakened German armies in the West and helped unravel the Schlieffen Plan.

The Miracle of the Marne

Throughout August, German soldiers overran Belgium and poured into northern France. Belgian and French soldiers fought bravely, but the Germans overwhelmed them with a steady, costly advance. By early September, the Germans were in position for a final drive on Paris. They planned to push west along the Marne, a river that flowed out of the French capital.

Over the course of one week, September 5–12, the French and some newly arrived British troops blunted the German advance, foiling Germany’s attempt to conquer Paris and win a quick victory with its Schlieffen Plan. The scale of the fighting was immense and so were the losses. More than 2.5 million troops were involved in the battle. Both sides suffered more than 250,000 casualties. This Allied victory saved Paris and became known as the “Miracle of the Marne.”

During this battle, the French abandoned their Plan XVII and redeployed troops from all over their country to plug gaps in the line and stop the German advance. The French even used 600 Paris taxicabs to ferry infantry troops into battle. Some historians still call these troops “The Taxicab Army.”

During this battle, the French abandoned their Plan XVII and redeployed troops from all over their country to plug gaps in the line and stop the German advance. The French even used 600 Paris taxicabs to ferry infantry troops into battle. Some historians still call these troops “The Taxicab Army.”

The trench stalemate

After the Miracle of the Marne, neither side could gain a decisive advantage. The war on both fronts soon settled into an uneasy stalemate between antagonists with highly developed industry and technology. The power of industrialization manifested itself in a variety of deadly, cutting-edge weapons. The killing power of new weapons such as point-detonated artillery shells, machine guns, grenades, airplanes, and poison gas made it difficult for attackers to capture objectives. For self-preservation against all of this firepower, soldiers dug deep trench networks that provided some semblance of cover. By the end of 1914, trenches crisscrossed the war’s landscape, both east and west.

The trenches were especially extensive in the West, where a continuous line snaked all the way from the English Channel to the neutral Swiss border. Try as they might, neither the Allies nor the Central Powers could break the awful trench stalemate and win the war. Between 1915 and 1917, they fought inconclusive but costly battles at such places as Ypres, Vimy Ridge, Verdun, and the Somme, but the stalemate continued. Hundreds of thousands of men were killed, wounded, captured, or incapacitated psychologically in these futile attacks to break the deadlock.

For the average French, German, British, or Belgian soldier, life in the trenches was miserable. The trenches were usually about 10 feet deep and buttressed with wooden, or perhaps concrete, beams. Floorboards provided some relief from the ever-present mud. The trenches were surrounded by reams of barbed wire. Soldiers ate prepackaged rations or, if they were lucky, the occasional hot meal. The no man’s land between enemy trench systems could be as large as 3 miles or as small as 70 yards. No man’s land was cratered with sodden shell holes full of rainwater or even dead, decomposing bodies. Soldiers in the trenches were often exposed to the elements, as well as artillery shells, sniper fire, machine gun fire, mortar fire, poison gas, and enemy raids. The trench experience was a hellish industrial war that raged 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

For the average French, German, British, or Belgian soldier, life in the trenches was miserable. The trenches were usually about 10 feet deep and buttressed with wooden, or perhaps concrete, beams. Floorboards provided some relief from the ever-present mud. The trenches were surrounded by reams of barbed wire. Soldiers ate prepackaged rations or, if they were lucky, the occasional hot meal. The no man’s land between enemy trench systems could be as large as 3 miles or as small as 70 yards. No man’s land was cratered with sodden shell holes full of rainwater or even dead, decomposing bodies. Soldiers in the trenches were often exposed to the elements, as well as artillery shells, sniper fire, machine gun fire, mortar fire, poison gas, and enemy raids. The trench experience was a hellish industrial war that raged 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Losing the eastern ally

In 1917, with the war in its fourth year, revolution swept through Russia. The nation’s armies had suffered millions of casualties, with little apparent gain or purpose. Bread riots were raging in Russian cities, and the country was in political turmoil. The tsar fell from power, and in late October, the Bolsheviks, a group of radical Communist revolutionaries, seized control of the government. The Bolsheviks were against the war, so they immediately negotiated a peace settlement with Germany.

Russia’s withdrawal from the war was devastating to the Allies because Germany could now focus its full attention on the western front. It redeployed most of its army to the West. At the same time, Germany unleashed its submarines throughout the Atlantic in an attempt to strangle Great Britain and win the war. In so doing, the Germans began attacks against ostensibly neutral American ships that were carrying food and war materiel (military equipment) to Britain.

Russia’s withdrawal from the war was devastating to the Allies because Germany could now focus its full attention on the western front. It redeployed most of its army to the West. At the same time, Germany unleashed its submarines throughout the Atlantic in an attempt to strangle Great Britain and win the war. In so doing, the Germans began attacks against ostensibly neutral American ships that were carrying food and war materiel (military equipment) to Britain.

Reacting to German Sea Tactics, the U.S. Declares War

For three years, Americans had watched in curious detachment as World War I raged in Europe. Initially, the majority of Americans were glad to stay out of the war. For instance, in 1916, President Woodrow Wilson used the slogan, “He kept us out of the war,” to win a tough reelection fight against his Republican opponent Charles Evans Hughes. However, within six months, Wilson led the country into the war. By that time, public opinion was firmly aligned with the Allies. Why? Americans were concerned about the consequences of a potential German-dominated Europe, and Americans were burning with anger over German unrestricted submarine warfare against American ships in the Atlantic.

On April 6, 1917, the United States officially entered the war on the Allied side when Congress declared war on Germany and the other Central Powers nations. This fateful declaration of war stemmed from four causes:

Ties to Britain and France

Global economics

A sense of global responsibility

Frustration with Germany over neutrality rights

Fighting to support our allies

During World War I, Germany was an autocracy, ruled by an elite group of aristocrats, military officers, and bureaucrats. The public face of this regime was Kaiser Wilhelm II, an imperialist monarch who garnered little sympathy in democratic America. By contrast, Britain and France were fellow democracies with leaders who derived their power from elections. The average American thus had a natural sympathy for these democracies in their fight against imperial Germany.

The British exploited this natural sympathy by engaging in a widespread propaganda campaign in America. In hopes of inciting moral outrage and persuading the U.S. to join the Allies, British propagandists circulated stories of German atrocities, some of which weren’t true. The campaign did succeed in stoking anti-German sentiment, though.

The British exploited this natural sympathy by engaging in a widespread propaganda campaign in America. In hopes of inciting moral outrage and persuading the U.S. to join the Allies, British propagandists circulated stories of German atrocities, some of which weren’t true. The campaign did succeed in stoking anti-German sentiment, though.

In January 1917, anti-German opinion increased when the British intercepted a German diplomatic communication and publicized it. This communication, known as the Zimmerman telegram, was a clumsy German attempt to enlist Mexico’s help in any potential war with the U.S. Arthur Zimmerman, the German foreign minister, promised Mexico the return of Texas, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and California, all of which Mexico had lost to the U.S. in a war fought between 1846 and 1848 (see Chapter 10 for the lowdown). Although the proposal went nowhere, Americans were outraged at these German schemes.

Fighting for free trade

Americans had a serious economic interest in the Allied cause. Between 1914 and 1916, the U.S. engaged in $3 billion worth of trade with the Allies each year. American bankers lent millions to Allied governments. American farmers were shipping large amounts of food to the Allied countries. Most significantly, the Allies were becoming increasingly dependent on American industrial goods, including armaments, to fight the war. If the Allies lost, many American investors, industrialists, and bankers stood to lose their shirts because a German-dominated Europe would be a less-than-welcoming place for American trade and goods.

Fighting for democracy and a better life

By 1917, many Americans believed that the U.S. must make the world safe for democracy. The prevailing notion was that the United States could and should spread democratic capitalism, self-determination, and freedom to every corner of the globe. To some extent, this was a continuation of Manifest Destiny, the popular American notion that the United States was a special empire of liberty destined to dominate the North American continent and spread its ideas far and wide (see Chapters 8, 10, and 12 for more on this concept).

American idealism also stemmed from a series of early 20th-century social reforms, known as Progressivism, to alleviate urban decay, poverty, monopolies, and injustice in America. President Wilson was a confirmed Progressive who envisioned the United States as a world leader. The bottom line was that the World War I era was an idealistic time.

Fighting against tyranny

Although the United States professed neutrality, it engaged in extensive trade, commerce, and even arms sales with the Allies, especially the British. The Germans believed that the Americans were neutrals in name only. So, at times, their submarines attacked and sank American ships or vessels with Americans aboard. Perhaps the most notorious example of this was the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915, with the loss of 128 American lives.

In early 1917, the Germans unleashed unrestricted submarine warfare and sank several American ships. American viewed this as outright butchery, and anti-German sentiment swept the country. The Wilson administration severed diplomatic relations with Germany. When Germany refused to end unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson and Congress saw no other recourse but war.

Wilson sums up America’s goals for the war

During World War I, President Wilson was the only war leader who announced a clear set of war aims. In an early 1918 speech, Wilson stated that the United States was fighting for 14 points and stated, point by point, exactly what he meant. The Fourteen Points, as they came to be called, basically stood for the following ideas:

An international world of free trade with freedom of the seas and no economic barriers. This would create prosperity and reduce the chances of more wars because nations that do business with one another rarely go to war.

More-open diplomacy because secret deals had contributed to the onset of World War I.

Self-determination for all peoples to create their own autonomous, independent nations.

The establishment of a world peacekeeping body known as the League of Nations.

Preparing the Home Front for War

The United States was not well prepared for World War I. This was a major reason why the Germans had been so belligerent in the months leading up to the American declaration of war. The Germans had little respect for American military prowess because the U.S. Army was small and the U.S. Navy wasn’t ready for war. “What can [America] do?” German Gen. Erich Ludendorff dismissively asked a colleague. “She cannot come over here! I don’t give a damn about America.”

Indeed, when Congress declared war, some American leaders believed that the U.S. would mainly contribute naval and economic support for the Allied war effort. “You’re not actually thinking of sending soldiers over there, are you?” one senator naively asked a general in April 1917. Soon reality set in. The only way to win the war was to send large numbers of soldiers to Europe, and this would require a massive mobilization that had a dramatic effect on the country.

Drafting men for war

After the declaration of war, hundreds of thousands of young men flocked to recruiting stations to join the armed forces. Still, the war effort needed more. In May 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, in effect implementing a military draft.

About 10 million men between the ages of 21 and 30 registered for selective service, a benign term the Wilson administration used instead of the word draft with its coercive connotations. Of these 10 million men, the armed forces took 2.75 million into service. Overall, some 5 million Americans served in the military during World War I, so a little more than half were draftees.

The draft affected young, unmarried men the most — 90 percent of draftees were single. Married men, farmers, and essential war industries workers had a fairly easy time obtaining deferments from the draft.

Expanding the federal government

The wartime mobilization required an expansion in the size of the federal government. In June 1917, Wilson created the important War Industries Board (WIB) under Bernard Baruch, a wealthy financier and longtime supporter of the president. The WIB purchased military equipment, encouraged businesses to adopt mass-production techniques, and made it worthwhile to do so by dispensing lucrative federal contracts. The agency also allocated and rationed vital resources such as rubber, steel, and wood. The WIB was the single-most-important wartime agency.

Wilson created several other important agencies to run the war:

The Fuel Administration regulated coal and oil prices as well as consumption of those two fuels. It also implemented daylight saving time, which is, of course, still with us today.

The Food Administration oversaw the production and import of food not only to American soldiers but to the entire Allied world. By 1918, the U.S. was providing most of the food that the Allied population ate.

The Committee on Public Information (CPI) sold war bonds, spread pro-war propaganda, and circulated anti-German stories, sometimes in Hollywood films. The ultimate goal of CPI was to keep public opinion in favor of the war.

The Food Administration was headed up by Herbert Hoover, a future president. Hoover succeeded in maximizing American food production and feeding America’s allies, while avoiding rationing here at home. After the war, he organized food shipments for millions of hungry Europeans. Hoover’s success with the Food Administration propelled him into a national political career, all the way to the Oval Office.

The Food Administration was headed up by Herbert Hoover, a future president. Hoover succeeded in maximizing American food production and feeding America’s allies, while avoiding rationing here at home. After the war, he organized food shipments for millions of hungry Europeans. Hoover’s success with the Food Administration propelled him into a national political career, all the way to the Oval Office.

Gaining from the war

The American economy did very well during World War I. With the great demand for food, American farm production grew by 25 percent. Farmers made handsome profits by selling their crops to the government. Industrialists also found plenty of markets for such products as bullets, rifles, ships, locomotives, tin cans, and the like. For instance, American factories produced 20 million artillery shells for Allied armies. Overall, industrial production grew by one-third during the war years. All of this growth led to the creation of millions of jobs and a 20 percent rise in wages for the average American worker.

Hiring women to do “man’s work”

The wartime mobilization of men into the military created economic opportunities for women. Many found white-collar work as clerks, secretaries, bookkeepers, and typists. Some worked on factory production lines in hard-hat jobs that had traditionally been done by men. A few thousand young women served overseas in relief agencies like the Red Cross. Thousands more served in the Army, mainly as nurses.

Female leaders hoped that the war would lead to greater economic, political, and cultural equality for women. But, when the war ended, so did opportunity for change. Quite commonly, women lost their jobs to returning veterans. The average American, male and female, still believed that a woman’s proper place was in the home as a mother. The only significant long-term change that women earned from the war was the right to vote (suffrage). In 1919, under intense pressure from idealist feminist reformers, Congress passed a national suffrage amendment to the Constitution, giving voting rights to American women.

Female leaders hoped that the war would lead to greater economic, political, and cultural equality for women. But, when the war ended, so did opportunity for change. Quite commonly, women lost their jobs to returning veterans. The average American, male and female, still believed that a woman’s proper place was in the home as a mother. The only significant long-term change that women earned from the war was the right to vote (suffrage). In 1919, under intense pressure from idealist feminist reformers, Congress passed a national suffrage amendment to the Constitution, giving voting rights to American women.

Setting aside differences

During the war, the Committee on Public Information (CPI) made a special effort to reach out to minorities, especially blacks. Using the slogan “We’re all in this together,” the CPI encouraged all Americans to do their part to win the war. Most black Americans lived as second-class citizens, especially in the South. Racist Jim Crow laws prevented them from voting and segregated them from whites in almost every way imaginable.

With CPI’s inclusive appeal, African Americans hoped that the war would lead to greater equality and justice. Half a million blacks left the South for the North, mainly in search of war-related jobs. They found greater economic opportunity than ever before. By 1920, 1.5 million blacks were working in northern factories. Although they made more money and earned greater benefits than ever before, they still did not enjoy any semblance of equality with whites.

Some 260,000 black men served in the segregated armed forces, mostly in all-black support units that were commanded by white officers. A few thousand black soldiers saw combat in France, but, reflecting white society’s racist, erroneous belief that blacks would not fight, the vast majority of black servicemen worked in menial jobs as laborers, stevedores (people who load and unload ships), or mess stewards (waiters, kitchen staff, and cooks).

Opposing the war

Although World War I was a popular war, some Americans were against it. Some ethnic Germans felt an affinity for their original homeland and couldn’t take up arms against it. They had to be very careful about voicing any opposition, though, or they risked being the targets of anti-German hysteria. During the war, Americans smashed German-language printing presses, eradicated the German language from schools, removed German books from libraries, and, at times, forced German Americans to pledge allegiance to or kiss the American flag to prove their loyalty.

Anti-German sentiment was so strong during the war that Americans came up with a new name for hamburgers because the word sounded too German. Instead they called them “liberty patties.”

Anti-German sentiment was so strong during the war that Americans came up with a new name for hamburgers because the word sounded too German. Instead they called them “liberty patties.”

Socialists, Communists, anarchists, pacifists, and feminists also opposed the war on moral grounds. President Wilson was contemptuous of these dissenters. “What I am opposed to is not [their] feeling . . . but their stupidity. I want peace, but I know how to get it. They do not.” The president signed two anti-dissent bills into law, the Espionage Act and the Sedition Amendment, both of which he used to jail about 1,500 antiwar activists. In so doing, he fostered a national mood of intolerance and fear.

Joining the Fray in Phases

Realistically, the U.S. could provide little significant military help to the Allies for about a year. It took more than 12 months to conscript, train, and send an army overseas. The Americans also had to learn to work with their British allies to counter the German submarine threat in the Atlantic, and that took time as well. Consequently, American soldiers didn’t enter combat in any kind of substantial numbers until well into the spring of 1918.

Clearing the seas of German submarines

The German navy maintained a force of 32 to 36 submarines on patrol in the Atlantic. Their job was to sink so many Allied supply and troop ships that Britain would collapse and the United States would be marginalized. As of the spring of 1917, German subs were sinking a staggering 600,000 tons of shipping per month. At this rate, the Allies would lose the war.

At the urging of Adm. William Sims, commander of the U.S. Atlantic fleet, the Allies implemented an elaborate convoy system that was designed to protect the vulnerable, but valuable, ships that carried cargo and troops. Excellent submarine-killing ships, such as destroyers, now escorted the merchant ships across the Atlantic. Over time, the system turned the tide of the war in the Atlantic. Sinkings of merchant ships declined. Sinkings of German submarines increased. This important victory secured Britain’s vital sea lanes and allowed the United States to ship a mass army to Europe.

Increasing the American presence in Europe

In a little more than one year, the United States Army expanded from a force of about 100,000 professional soldiers to a mass army of millions. The American presence in Europe in 1917 was a token force of 14,000 soldiers. One year later, that same detachment, known as the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), had ballooned to 1 million men and counting. At that point, 8,000 new American troops were entering France every day. Most still needed more training to be ready for the trenches, but at least they were there. By the fall of 1918, the AEF counted 2 million soldiers in its ranks.

The commander of this enormous army was Gen. John Pershing. He was known throughout the Army as “Black Jack” because he had once served in the 10th Cavalry Regiment, an African American unit. A thoughtful but prickly man, Pershing saw the AEF as the very embodiment of American national sovereignty.

In the spring of 1918, even as the AEF was arriving, the Germans launched a major offensive designed to win the war. They devised effective new tactics to breach the trenches and punched major holes in the Allied lines. French and British commanders desperately needed American manpower to replace their devastating losses. They pressured Pershing to feed his men piecemeal into the trenches wherever they were needed, under British or French commanders. But, even though Pershing was still dependent upon his allies to train and equip his newly arrived units, he refused. To him, the autonomy of his AEF was paramount. If the French and British wanted American help, they would have to deal with the U.S. as equals.

In the spring of 1918, even as the AEF was arriving, the Germans launched a major offensive designed to win the war. They devised effective new tactics to breach the trenches and punched major holes in the Allied lines. French and British commanders desperately needed American manpower to replace their devastating losses. They pressured Pershing to feed his men piecemeal into the trenches wherever they were needed, under British or French commanders. But, even though Pershing was still dependent upon his allies to train and equip his newly arrived units, he refused. To him, the autonomy of his AEF was paramount. If the French and British wanted American help, they would have to deal with the U.S. as equals.

Engaging the enemy on the ground

By May 1918, the Germans had torn a 40- by 80-mile gap in the Allied lines. They were advancing west on a broad front through France, roughly from Arlon in the north to Amiens in the south. Both sides had suffered a quarter-million casualties in just over a month of fighting.

The Germans were engaged in a race against time. Germany was suffering from famine, massive casualties, war weariness, and manpower problems. But, with Russia out of the war, the German army in the West was strong enough to unleash this final push for victory. So the commanders were desperate to administer a knockout blow to the Allies before the Americans could seriously influence the fighting.

The Germans were engaged in a race against time. Germany was suffering from famine, massive casualties, war weariness, and manpower problems. But, with Russia out of the war, the German army in the West was strong enough to unleash this final push for victory. So the commanders were desperate to administer a knockout blow to the Allies before the Americans could seriously influence the fighting.

Cantigny, Chateau Thierry, and Belleau Wood

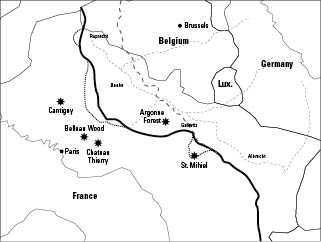

As of May, the Americans finally began to enter combat in large numbers (see Figure 14-2). Between May 28 and June 2, the 1st Infantry Division, one of the Army’s most famous units, successfully counterattacked and captured the village of Cantigny, helping blunt the German offensive in Picardy province.

Figure 14-2: Map of the American Expeditionary Force on the western front, 1918.

The 1st Infantry Division’s nickname is the “Big Red One.” One of its subunits, the 28th Infantry Regiment, earned the moniker “The Black Lions of Cantigny” for its valor in taking that town. Most unit members shorten the name to “Black Lions.”

The 1st Infantry Division’s nickname is the “Big Red One.” One of its subunits, the 28th Infantry Regiment, earned the moniker “The Black Lions of Cantigny” for its valor in taking that town. Most unit members shorten the name to “Black Lions.”

About 20 miles southwest of Cantigny, the Germans were on the move, attempting to capture Paris. In June, two U.S. Army divisions, the 2nd and 3rd, pushed the Germans back at Chateau Thierry, about 40 miles east of Paris. Nearby, the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments, collectively known as the “Devil Dogs,” fought the Germans in a thick forest known as the Belleau Wood. The Marines were outnumbered four-to-one. Like two colliding rams, they attacked east as the Germans attacked west. At times they fought hand-to-hand with bayonets, an extremely rare phenomenon in modern combat. In one attack, Gunnery Sgt. Dan Daly, a man who earned two Medals of Honor, urged his men forward with a famous line: “Come on, . . . do you want to live forever?” By the end of June, the Germans were in headlong retreat to the east, away from Belleau Wood.

The Marines earned coast-to-coast headlines for their exploits at the Battle of Belleau Wood. Stories of Marine valor screamed from the front pages of many daily newspapers. Almost overnight, the Marine Corps went from an obscure, tiny force of maritime troops to the most famous and publicly admired of the armed services (see Chapter 4 for more on Marine Corps history). Army soldiers had also fought bravely at Belleau Wood, but they received little of the credit for victory. Soldiers accused the Marines of “cheap advertisement in order to glorify their own cause,” and resented that the Marines got most of the glory. Believe it or not, the resentment continues to this day.

The Marines earned coast-to-coast headlines for their exploits at the Battle of Belleau Wood. Stories of Marine valor screamed from the front pages of many daily newspapers. Almost overnight, the Marine Corps went from an obscure, tiny force of maritime troops to the most famous and publicly admired of the armed services (see Chapter 4 for more on Marine Corps history). Army soldiers had also fought bravely at Belleau Wood, but they received little of the credit for victory. Soldiers accused the Marines of “cheap advertisement in order to glorify their own cause,” and resented that the Marines got most of the glory. Believe it or not, the resentment continues to this day.

Holding on at the Marne

After Belleau Wood, time had nearly run out for the Germans. Having suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties, the Germans possessed only enough strength for one last attempt to take Paris. They planned to push across the Marne River (where the French had stopped them four years before), swing west, and take Paris from that direction.

After Belleau Wood, time had nearly run out for the Germans. Having suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties, the Germans possessed only enough strength for one last attempt to take Paris. They planned to push across the Marne River (where the French had stopped them four years before), swing west, and take Paris from that direction.

On July 15, at a key point on the Allied Marne River line, the German army launched powerful attacks against the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division. Following a massive artillery bombardment, German soldiers hurled themselves at the 3rd Division trenches. All up and down the line, the Americans fought back with everything they had. They killed hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of enemy soldiers. In one sector, two full platoons (about 50 men to a platoon) literally fought to the last man, inflicting ruinous casualties on the attacking Germans.

On July 15, at a key point on the Allied Marne River line, the German army launched powerful attacks against the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division. Following a massive artillery bombardment, German soldiers hurled themselves at the 3rd Division trenches. All up and down the line, the Americans fought back with everything they had. They killed hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of enemy soldiers. In one sector, two full platoons (about 50 men to a platoon) literally fought to the last man, inflicting ruinous casualties on the attacking Germans.

By July 17, the German offensive was shattered. The Allies went on the counteroffensive, crossing the Marne River and chasing the Germans north and east, away from Paris. The French capital was saved, and the tide of the war had turned.

The 3rd Infantry Division’s epic stand at the Marne River forever earned the unit the nickname “Rock of the Marne.” Even today, when you enter the division’s post at Fort Stewart, Georgia, the guards, instead of saying hello, greet you with the unit’s unique identity: “Rock of the Marne, sir!”

The 3rd Infantry Division’s epic stand at the Marne River forever earned the unit the nickname “Rock of the Marne.” Even today, when you enter the division’s post at Fort Stewart, Georgia, the guards, instead of saying hello, greet you with the unit’s unique identity: “Rock of the Marne, sir!”

Going on the offensive

After the Marne victory, the Allies were now clearly winning the war. With this new momentum, they began a series of attacks, pushing the Germans steadily east, closer to their border.

Gen. Pershing wanted to continue attacking east, overwhelm a German salient (the part of the battle line closest to the Allies) at St. Mihiel, knife into Germany, and take the town of Metz. He saw this as the first step in the ultimate conquest of Germany. However, his French and British colleagues wanted to push the Germans out of France first. They persuaded Pershing to participate in an all-Allied momentous offensive to overwhelm the Germans and kick them off French soil for good. For the AEF, this meant launching an offensive into the Argonne Forest, straight into a formidable network of German trench systems.

Gen. Pershing wanted to continue attacking east, overwhelm a German salient (the part of the battle line closest to the Allies) at St. Mihiel, knife into Germany, and take the town of Metz. He saw this as the first step in the ultimate conquest of Germany. However, his French and British colleagues wanted to push the Germans out of France first. They persuaded Pershing to participate in an all-Allied momentous offensive to overwhelm the Germans and kick them off French soil for good. For the AEF, this meant launching an offensive into the Argonne Forest, straight into a formidable network of German trench systems.

The Battle of Argonne Forest began on September 26, 1918, and lasted until November 11 of that same year. About 1.2 million American soldiers participated (see Figure 14-3). For them, the battle was beyond nightmarish. The weather was rainy and chilly. The forest dripped with menace. The ground was muddy and sloppy. For the soldiers, attacking meant venturing into kill zones, being exposed to artillery, mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire, plus some poison gas too. Troops were cold, sick, hungry, dirty, tired, and frightened out of their wits. The Americans steadily gained ground, but casualties were staggering. In one typical example, the 7th Infantry Regiment lost close to 2,300 men, out of an original strength of 3,000, in 28 days on the line. Even so, they were still receiving orders to attack.

The Battle of Argonne Forest began on September 26, 1918, and lasted until November 11 of that same year. About 1.2 million American soldiers participated (see Figure 14-3). For them, the battle was beyond nightmarish. The weather was rainy and chilly. The forest dripped with menace. The ground was muddy and sloppy. For the soldiers, attacking meant venturing into kill zones, being exposed to artillery, mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire, plus some poison gas too. Troops were cold, sick, hungry, dirty, tired, and frightened out of their wits. The Americans steadily gained ground, but casualties were staggering. In one typical example, the 7th Infantry Regiment lost close to 2,300 men, out of an original strength of 3,000, in 28 days on the line. Even so, they were still receiving orders to attack.

Figure 14-3: After capturing a line of German trenches in Argonne Forest, American soldiers take a break from battle.

© CORBIS

Argonne Forest is the costliest battle in American military history. The AEF lost 26,277 men killed, more than 95,000 wounded, and an undetermined number of sick, shell-shocked, and missing men. Horrible though it was, the battle contributed to the eventual defeat of Germany.

Argonne Forest is the costliest battle in American military history. The AEF lost 26,277 men killed, more than 95,000 wounded, and an undetermined number of sick, shell-shocked, and missing men. Horrible though it was, the battle contributed to the eventual defeat of Germany.

The Imperfect Armistice

With the Allies relentlessly attacking and their armies swelling with American manpower, the Central Powers nations began collapsing, one after another. In late October, Austria-Hungary disintegrated, as did Bulgaria. Germany too was at the end of its endurance. Food shortages, political turmoil, and the failure of the 1918 offensives all led to a revolution in early November. Under pressure from a new democratic-style government called the Weimar Republic, the kaiser abdicated and fled to Holland.

The Weimar Republic negotiated an immediate armistice (or a truce called in anticipation of a peace treaty) with the Allies. It took effect at exactly 11:11 a.m. on November 11, 1918. This terrible war claimed the lives of 10 million people, including 110,000 Americans.

When the new German government concluded the armistice, it hoped to negotiate a binding peace treaty on the basis of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Instead, the Allied powers met in 1919 at Versailles, just outside of Paris, and dictated harsh peace terms to a weak Germany that had little choice but to accept them. These terms were known as the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson was against the harsh treaty, but he found himself overruled time and again by his British and French allies, who thought the draconian treaty would prevent Germany from ever threatening its European neighbors again.

The Treaty of Versailles imposed the following terms:

Germany was blamed for the outbreak of the war as a justification for its punishment.

Germany lost one-tenth of its land and population to France, Poland, and several other European countries.

Germany lost all of its colonies. They mostly went to Britain and Japan.

Germany would abolish its navy and air force, and cut its army to a mere 100,000 soldiers.

Germany would pay $33 billion worth of reparations (money paid by a losing country to the victors to offset their economic losses) to the Allies, primarily the French.

The Treaty of Versailles was the kind of peace agreement that could be dictated and enforced only by total victors, but the Allies had earned only a partial victory in this war. They had not conquered Germany. Nor had they even forced the surrender of Germany’s armed forces. This meant that, in the long run, they would have difficulty enforcing the treaty’s severe provisions. It also guaranteed that a resentful Germany would someday seek to redress, or avenge, what Germans perceived as an unjust peace agreement. Thus, the real tragedy of World War I was that it did not solve enough of the issues that had led to war in the first place. Instead, it was only the bloody precursor to a far more terrible war fought by the next generation.

The Treaty of Versailles was the kind of peace agreement that could be dictated and enforced only by total victors, but the Allies had earned only a partial victory in this war. They had not conquered Germany. Nor had they even forced the surrender of Germany’s armed forces. This meant that, in the long run, they would have difficulty enforcing the treaty’s severe provisions. It also guaranteed that a resentful Germany would someday seek to redress, or avenge, what Germans perceived as an unjust peace agreement. Thus, the real tragedy of World War I was that it did not solve enough of the issues that had led to war in the first place. Instead, it was only the bloody precursor to a far more terrible war fought by the next generation.