Chapter 15

The Looming Crisis: World War II before American Involvement

In This Chapter

A new era of Fascism

Hitler conquers Europe

Quarreling with the Japanese over Asia and the Pacific

World War II is considered the most devastating war human beings have ever fought. It is probably the most cataclysmic event in the history of humankind. By even the most conservative estimates, it cost the lives of 62 million people. The war affected more than half of the globe’s population at that time. World War II included the deliberate fire bombing of cities and civilians, the advent of nuclear weapons, the total mobilization of warring societies, titanic amphibious invasions, the conquest of weak nations, and the systematic extermination of millions of human beings in both Europe and Asia.

In short, World War II is a story of enormous drama and tragedy. So why did it happen? To a great extent, World War II grew from the problems left unresolved after World War I with the Treaty of Versailles (for more details, see Chapter 14). That treaty ended World War I, but it punished Germany severely, creating a great deal of resentment, plus a shaky economy and government in that country. At the same time, a rising industrial Japan, craving resources, wanted to conquer a large empire in Asia and the Pacific, thus challenging a shaky balance of power that the United States hoped to preserve. Britain and France were so devastated by World War I that they had difficulty summoning the strength to enforce the tenuous peace that followed that war. Two other major powers, Soviet Russia and the United States, were deeply preoccupied with their own domestic affairs and thus chose to remain aloof from these growing European problems until it was too late.

In this chapter, I trace the rise of aggressive, conquest-minded Fascist movements in Germany, Italy, and Japan. I explain how those movements directly challenged peace and stability, ultimately plunging the world into a ruinous war. Finally, I outline how the United States became involved in a war that most of its citizens hoped to avoid.

Reacting to Unrest, Fascism Emerges

No one was really happy with the outcome of World War I. In general, the citizens of the Allied countries mourned their millions of dead and vowed to avoid future war at nearly any cost. Some Allied nations even felt betrayed by the Treaty of Versailles. Italy, for instance, felt that it didn’t receive the territory its Allied partners promised for entering the war on their side. The United States was deeply disillusioned by its participation in the war, mainly because of the flawed peace that followed. By far, the Germans were the most disaffected of all. The average German hated the Treaty of Versailles that cost Germany one-tenth of its land and population, all of its colonies, and most of its armed forces. Plus, the treaty forced Germany to pay expensive reparations to the Allies, and this stunted German economic growth.

This unhappy situation proved to be an ideal breeding ground for an ideology called Fascism. Fascists believed in total government control of society — no freedom of speech, worship, assembly, or dissent — just absolute state control for the common good. To Fascists, the individual meant nothing. The collective was everything, especially the nation-state. Fascists also believed that some races, or ethnic groups, were inherently superior to others. In their view, some people were naturally strong and others were naturally weak. Moreover, the strong must survive at the expense of the weak. Fascism stood for might-makes-right, conquest, and an end to parliamentary democracy, natural human rights, capitalism, and common decency. Fascism appealed to disaffected youths who yearned for security, power, and a sense of belonging to a mass movement.

Difficult economic times helped Fascist parties come to power in Italy in 1922 and Germany in 1933. The German Fascists were known as the Nazis, an acronym for National Socialist German Worker’s Party. The Nazi Party originated as a tiny, ultranationalist political group in southern Germany in the early 1920s. By the early 1930s, when a serious economic depression gripped Germany, the Nazis had steadily grown into a large, powerful entity, appealing to millions of Germans at a time of high unemployment and deep anxiety. This was their path to power in 1933. In Europe, the two prominent Fascist leaders were Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany.

Difficult economic times helped Fascist parties come to power in Italy in 1922 and Germany in 1933. The German Fascists were known as the Nazis, an acronym for National Socialist German Worker’s Party. The Nazi Party originated as a tiny, ultranationalist political group in southern Germany in the early 1920s. By the early 1930s, when a serious economic depression gripped Germany, the Nazis had steadily grown into a large, powerful entity, appealing to millions of Germans at a time of high unemployment and deep anxiety. This was their path to power in 1933. In Europe, the two prominent Fascist leaders were Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany.

Mussolini rises to power

Mussolini was a World War I veteran and former Socialist, who formed the Italian Fascist Party after the war. In 1922, with civil war a real threat in Italy during a period of deep economic crisis, he came to power because his political rivals viewed his Fascists as a better alternative to Communism. Once in power, Mussolini and his party gradually assumed total control of the government.

Hitler slithers up the career ladder

Adolf Hitler also came to power peacefully. Like Mussolini, he had fought in World War I, although he saw much more combat than Mussolini ever did. An ardent German nationalist, Hitler was devastated by Germany’s defeat. He joined the Nazi Party, quickly assumed control of it, and dedicated his life to politics.

In 1923, after an abortive attempt to take over the German government, Hitler decided that he would win power peacefully from within, then destroy democracy once in power. Starting in 1933, when he became chancellor, the number-one post in German government (see Figure 15-1), this was exactly what he did. He and his Nazis ruled Germany with the following popular ideas:

Restore Germany to its rightful place as a military colossus and leading world power.

Reject the Treaty of Versailles.

Use a public works project to rejuvenate the German economy.

Persecute the Jews. Hitler and the Nazis were deeply hateful anti-Semites. They despised Jews and believed them to be the ultimate enemies of European civilization. These beliefs were widely held in Germany and Europe at that time.

Conquer a vast German empire in Europe. This was, of course, a secret agenda, but it was Hitler’s long-term plan.

Figure 15-1: Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

Hitler was actually born in Austria, not Germany. As a young man, his greatest ambition in life was to become an artist. He twice applied to and failed to get into the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Because anyone wanting to become a successful artist in Austria at that time needed this kind of formal training, his career as an artist was over before it started. He ended up on the streets of Vienna, living an aimless life, painting postcards for tourists. His dead-end life only concluded with the start of World War I, when he joined the German army.

Hitler was actually born in Austria, not Germany. As a young man, his greatest ambition in life was to become an artist. He twice applied to and failed to get into the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Because anyone wanting to become a successful artist in Austria at that time needed this kind of formal training, his career as an artist was over before it started. He ended up on the streets of Vienna, living an aimless life, painting postcards for tourists. His dead-end life only concluded with the start of World War I, when he joined the German army.

Itching for War, Germany Rearms and Expands

Of the two Fascist dictators, Hitler was by far the more dangerous for two reasons. First, he was much more committed to conquest and repression than Mussolini. Second, Germany was inherently more powerful than Italy because of Germany’s industry, economy, military traditions, and educated population. Once in power, Hitler wasted little time in defying the Treaty of Versailles, rearming Germany, and agitating for the return of territory Germany had lost because of the treaty. From 1935 to 1938, Germany grew stronger militarily, and as that happened, Hitler became steadily more provocative:

March 1935: Hitler announced that Germany would begin building an air force and expanding its army.

March 1936: Hitler sent troops into the Rhineland, a western section of Germany that the Treaty of Versailles had demilitarized.

August 1936: Hitler secretly began planning for war.

November 1937: Hitler informed his generals that Germany would soon launch an aggressive war of conquest.

March 1938: Hitler invaded and annexed Austria without firing a shot. Most Austrians didn’t resist because they favored the annexation.

The infamous Munich Agreement

As Hitler’s Germany made all of these aggressive moves in the 1930s, the British and French were content to stand aside and watch. The political leaders of those countries, most notably Neville Chamberlain of Britain, believed in a policy called appeasement. Knowing that the Treaty of Versailles had been unfair, they would not fight to enforce it. They wanted to avoid war at all costs, so they chose to appease Hitler by giving him what he wanted in exchange for peace.

In the summer of 1938, Hitler made new demands that led to a serious war scare in Europe. He demanded that democratic Czechoslovakia, a nation created by the Treaty of Versailles, return a province called the Sudetenland back to Germany. The Sudetenland was primarily composed of ethnic Germans and had once been part of Germany, but the Allies had given it to Czechoslovakia after World War I. Hitler made it very clear that if he did not get the Sudetenland through diplomacy, he would invade it and take it.

The Czechs were determined to hold on to the Sudetenland. Czechoslovakia had an alliance with France so, if the Germans did invade, the French (and probably Britain) would be compelled to declare war on Germany. Wanting to avoid this, Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, the French premier, engaged in a series of negotiations with Hitler. On September 29, 1938, they met with Hitler in Munich. Over the course of two days, they gave him everything he wanted and more. The Munich Agreement prevented war but at the terrible price of betraying a democratic ally. Hitler had pledged that the Sudetenland would be his last territorial demand, but six months later, he broke the Munich Agreement and swallowed up major portions of Czechoslovakia.

The Czechs were determined to hold on to the Sudetenland. Czechoslovakia had an alliance with France so, if the Germans did invade, the French (and probably Britain) would be compelled to declare war on Germany. Wanting to avoid this, Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, the French premier, engaged in a series of negotiations with Hitler. On September 29, 1938, they met with Hitler in Munich. Over the course of two days, they gave him everything he wanted and more. The Munich Agreement prevented war but at the terrible price of betraying a democratic ally. Hitler had pledged that the Sudetenland would be his last territorial demand, but six months later, he broke the Munich Agreement and swallowed up major portions of Czechoslovakia.

The post-Munich perspectives of three key leaders tell us a lot about the tragedy of what happened there:

The post-Munich perspectives of three key leaders tell us a lot about the tragedy of what happened there:

Neville Chamberlain returned to England to tell a cheering crowd that the Munich Agreement would mean “peace for our time.” He also expressed the opinion that Hitler could be trusted to keep his word.

Hitler was angry at the outcome of the conference because he actually wanted war. He was also deeply contemptuous of Chamberlain, a man he thought of as a weakling “who spoke the ridiculous jargon of an outmoded democracy.” Hitler fantasized about jumping on Chamberlain’s stomach in front of photographers.

Winston Churchill, the one major politician in Britain who spoke out against the Munich Agreement and appeasement in general, made a gloomy, but chillingly accurate prediction. “We have suffered a total and unmitigated defeat. . . . Czechoslovakia will be engulfed in the Nazi regime. . . . Do not suppose that this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning.”

The Nazi-Soviet Pact

In 1939, with the ink hardly dry on the Munich Agreement, Hitler began badgering Poland to return the Danzig Corridor, a slice of territory Germany had lost to Poland because of the Treaty of Versailles. The bitter aftermath of the Munich Conference had finally taught Chamberlain that negotiations with Hitler were pointless. He announced that Britain was preparing for war and would fight alongside Poland if Hitler invaded the Danzig Corridor. France did the same.

Hitler was skeptical that the Western powers would really go to war over Poland. But, just in case, he signed a nonaggression treaty, known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact, with the Soviet Union on August 23. This prevented the Russians from allying themselves with the British and French against Germany, as had happened in World War I (see Chapter 14 for more). Even though Nazi Germany and Communist Russia were bitter ideological enemies, at this point they both found it convenient to remain at peace with each other. In a secret and very cynical clause in the pact, the Germans and Soviets agreed to carve up Poland and the Baltic States between them.

Hitler approved the pact to give himself a free hand to invade Poland and then fight the Western powers without any interference from the Soviets. Josef Stalin, the Soviet leader, signed the pact because his country wasn’t prepared for war. Plus, he knew that the pact’s secret provisions would give Russia some significant territorial gains.

Bringing the Axis to Bear, War Breaks Out

Bolstered by the Nazi-Soviet Pact, in late August Hitler increased his pressure on Poland to give him the Danzig Corridor. The Poles, knowing what had happened to the Czechs the year before, refused to comply. By now Hitler’s appetite for war was considerable. He wanted to make Germany the dominant power in Europe (and after that, the world), and he believed Poland was the first step toward that goal. He rejected a new round of peace-minded diplomacy from the Western powers and ordered his troops into Poland on September 1, 1939. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. As in World War I, their side was known as the Allies. The German side in this war was known as the Axis. World War II in Europe had begun.

When the war broke out, President Franklin D. Roosevelt immediately declared that the United States would remain neutral. Polls showed that 99 percent of the American people favored this neutrality. A full 70 percent thought that U.S. involvement in World War I had been a mistake. The vast majority of Americans sympathized with the Allies but didn’t want to get involved in another European war.

When the war broke out, President Franklin D. Roosevelt immediately declared that the United States would remain neutral. Polls showed that 99 percent of the American people favored this neutrality. A full 70 percent thought that U.S. involvement in World War I had been a mistake. The vast majority of Americans sympathized with the Allies but didn’t want to get involved in another European war.

Overrunning Poland

The German army was larger, more mechanized, and better trained than the Polish army. Plus, the Germans possessed a premier air force (known as the Luftwaffe) that could bomb Polish cities or strafe (fire machine guns or cannon from low-flying planes) Polish troops. Consequently, when the Germans invaded Poland, they overwhelmed the Polish defenders in the border areas and advanced rapidly, deep into Poland.

The Poles fought valiantly but they were overmatched. The British and French were too far away to provide much help to their Polish allies. To make matters worse, on September 17, the Soviets, acting on the secret protocols in the Nazi-Soviet Pact, invaded eastern Poland. By October 1, the Russians and Germans had conquered Poland, beginning a long ordeal of foreign occupation for the Polish people. Proportionally, no population suffered more in World War II. Six million Poles, half of them Jews, were to die in this war.

The German conquest of Europe

After the fighting ended in Poland, nothing much happened in 1939. The British and French were content to build up their forces and wait for the Germans to make the first move in the West. Soldiers on both sides started calling this “The Phony War,” but it soon got very real.

In April 1940, the Germans successfully invaded Denmark and Norway. This secured Germany’s iron ore lifeline in the Atlantic and gave them numerous naval and air bases. The major blow came on May 10, 1940, when the Germans launched an all-out offensive against the British and the French in the West. The Germans invaded and conquered neutral Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg (see Figure 15-2). They also plunged into France.

Figure 15-2: Map showing Germany’s occupation of much of Europe in 1940 and 1941.

The Germans devised an elaborate plan to defeat the western Allies. The German army in the West had 3.3 million soldiers divided into three major army groups. One group held fast on the common border with France. To the north, another invaded Belgium and Holland, drawing major Allied reinforcements into that country. A third German army group knifed through the Ardennes Forest, breeched a thinly held section of the French line, and advanced deep into France, all the way to the English Channel in ten days. This cut off all Allied soldiers in Belgium. Rather than lose their whole army, the British evacuated more than 300,000 soldiers from Dunkirk back to England. The Germans followed up this victory by conquering the rest of France, including Paris.

The Germans devised an elaborate plan to defeat the western Allies. The German army in the West had 3.3 million soldiers divided into three major army groups. One group held fast on the common border with France. To the north, another invaded Belgium and Holland, drawing major Allied reinforcements into that country. A third German army group knifed through the Ardennes Forest, breeched a thinly held section of the French line, and advanced deep into France, all the way to the English Channel in ten days. This cut off all Allied soldiers in Belgium. Rather than lose their whole army, the British evacuated more than 300,000 soldiers from Dunkirk back to England. The Germans followed up this victory by conquering the rest of France, including Paris.

France surrendered on June 25, 1940. Most military analysts had expected another slow-moving, trench-style war in the West, similar to World War I, so the fall of France absolutely stunned the world. Hoping to feast on the spoils of German success, Mussolini’s Italy entered the war on the Axis side. Nazi Germany and its allies now dominated most of the European continent.

Flushed with victory, Hitler in the summer of 1940 offered to make peace with Britain, provided the British would acquiesce to German control of Europe. The British refused. By now, Churchill had come to power as prime minister. Defiant and stubborn, he represented a new fighting resolve in the British people. Hitler responded to this defiance by promising to invade Britain.

As a prelude to invasion, Hitler launched major air attacks against Britain’s cities and its Royal Air Force. In these air battles, known as the Battle of Britain, the Royal Air Force battled the Luftwaffe to a standstill. This saved Britain from invasion but, in practical terms, the British could do little on their own to challenge German supremacy in Europe. To do that, they would need allies.

Hitler invades the Soviet Union

By the end of 1940, Hitler had decided to betray the Nazi-Soviet Pact and invade the Soviet Union. In early 1941, he massed 3.2 million German soldiers along the common frontier with the Soviets. He enlisted the help of Fascist Romania, Italy, and Hungary for his plan. He also persuaded Finland to join him. Stalin’s spies, numerous diplomats, and British intelligence operatives all sniffed out German intentions, but the Soviet dictator refused to believe that Hitler would attack the Soviet Union.

Hitler decided to invade for the following reasons:

He was concerned that, given time, the Soviets would get stronger and one day attack Germany.

He believed that the British were essentially defeated in the West, freeing him to attack the Soviet Union in the East.

His master plan for Germany was to conquer vast amounts of living space (lebensraum) in Russia, at the expense of people he considered racially inferior.

He wanted to eliminate Communism in Russia.

He wanted to fight a racial war of extermination and enslavement against the Russians, Ukrainians, and Jews who populated the western part of the Soviet Union.

On June 22, 1941, the invasion began, thus initiating the largest, most destructive, ruthless war in human history. Throughout the summer and fall of 1941, the German juggernaut (a relentless, destructive force) crashed through eastern Poland, Ukraine, and deep into Russia. The Germans battered outclassed Soviet units with a combination of air, armor, and traditional infantry attacks. They encircled and captured hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers. By October, Soviet Red Army losses were in the millions, but German losses were heavy too. They suffered 900,000 casualties in 1941 alone.

Hitler believed he was on the verge of conquering Russia but, as fall turned into winter, subzero temperatures, supply problems, and stiffening Soviet resistance stopped the Germans just short of Moscow. The Germans had captured hundreds of miles of territory and had wounded the Russians. However, the Soviet Union was anything but conquered. The war in the East would now turn into a long struggle that favored the Soviets because of their nearly limitless manpower. Moreover, Germany was now facing enemies west and east. Although Churchill was no friend of Communism, he was happy to make common cause with the manpower-rich Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. “If Hitler invaded hell,” Churchill said, “I should at least make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.”

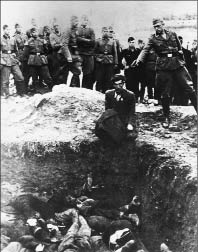

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, they immediately set in motion Hitler’s blueprint for a racial war of extermination. The Germans starved, neglected, tortured, and worked Soviet POWs to death. Any civilians who didn’t cooperate with the Germans were enslaved or shot. German army units and special SS death squads rounded up hundreds of thousands of Jews and shot them to death in mass executions. For instance, in September 1941, the Germans, over the course of three days, systematically executed 33,000 Jews at Babi Yar, just outside of Kiev. This kind of thing went on all over German-occupied Russia during that summer and fall of 1941 (see Figure 15-3). Ultimately, the Germans scaled down the executions and instead shipped Jews and other “undesirables” to death camps in Poland, where they were either gassed to death or worked as slaves.

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, they immediately set in motion Hitler’s blueprint for a racial war of extermination. The Germans starved, neglected, tortured, and worked Soviet POWs to death. Any civilians who didn’t cooperate with the Germans were enslaved or shot. German army units and special SS death squads rounded up hundreds of thousands of Jews and shot them to death in mass executions. For instance, in September 1941, the Germans, over the course of three days, systematically executed 33,000 Jews at Babi Yar, just outside of Kiev. This kind of thing went on all over German-occupied Russia during that summer and fall of 1941 (see Figure 15-3). Ultimately, the Germans scaled down the executions and instead shipped Jews and other “undesirables” to death camps in Poland, where they were either gassed to death or worked as slaves.

Figure 15-3: A member of the German SS, Einsatz Gruppen D, prepares to shoot a Polish Jew who is kneeling on the edge of a mass grave almost filled with victims.

© CORBIS

Fighting an undeclared war in the Atlantic

The German victories of 1940 and 1941 sent a collective shiver down the American spine. At the outset of war, most Americans complacently counted on the British and French to keep Germany at bay. Hitler’s conquest of Europe served as wake-up call of sorts. The American people still didn’t want to enter the war, but they now thought it prudent to prepare for war, just in case. President Roosevelt was a great proponent of this “short of war” policy. He had run for and won an unprecedented third term in the White House because he was so deeply concerned with the creeping threat resulting from Axis victories in Europe.

Roosevelt’s government implemented the following policies, all designed to help the Allies as much as possible and prepare the U.S. for war:

He traded 50 old warships — submarine hunters known as destroyers — to Britain for basing rights in the Caribbean.

He and the Congress passed the first peacetime draft in U.S. history.

He approved a massive naval rearmament program.

He implemented Lend-Lease, a policy of direct military aid to Britain and the Allies.

Lend-Lease revealed that the U.S. was neutral in name only, because the Americans were doing everything they could to help the Allies, short of entering the war themselves. By the late spring of 1941, the U.S. Navy was escorting Lend-Lease supplies to British waters. At the same time, German submarines were attempting to strangle Great Britain by cutting off its shipping lifeline to its overseas empire and America.

By summertime, the U.S. Navy was actually fighting an undeclared war with the German navy in the Atlantic. Sometimes the Americans even traded shots with the Germans. The Germans torpedoed several American ships, most notably the USS Reuben James which sank on October 31, with the loss of 115 American sailors.

In spite of these naval clashes, neither Germany nor the U.S. declared war in the fall of 1941 because the timing wasn’t right. President Roosevelt knew the United States was unprepared. He also understood that, in spite of American Navy casualties, the country was not yet in favor of another war with the Germans. For his part, Hitler was deeply absorbed with his war in Russia at the time and felt that, if and when Russia was conquered, he could take care of the United States in his own good time. Although he had little fear of the United States, he saw no reason to provoke war with the Americans just yet.

In spite of these naval clashes, neither Germany nor the U.S. declared war in the fall of 1941 because the timing wasn’t right. President Roosevelt knew the United States was unprepared. He also understood that, in spite of American Navy casualties, the country was not yet in favor of another war with the Germans. For his part, Hitler was deeply absorbed with his war in Russia at the time and felt that, if and when Russia was conquered, he could take care of the United States in his own good time. Although he had little fear of the United States, he saw no reason to provoke war with the Americans just yet.

Brewing Trouble in Asia and the Pacific

Just as things were heating up in Europe in the 1930s, over in Asia, Japan was at a crossroads. Decades of industrialization had turned the country into a significant military and economic power. But without such resources as oil, rubber, iron ore, tin, and bauxite (needed to make aluminum), Japan would always be dependent on the European colonial empires of Asia and the United States for these resources. In order for Japan to achieve autonomy and first-class status, it had to acquire resources in Asia and the Pacific — probably by conquest — but this might mean war with the Western powers because they all favored the status quo.

The Japanese government was dominated by a ruling clique of military officers, industrialists, and aristocrats who yearned for imperial greatness. Many of them embraced a Fascist belief in Japanese racial superiority and a national destiny of Far Eastern domination. Presiding over this aggressive mix of personalities was Emperor Hirohito, a godlike, distant figure who guided national policies but did not wield everyday power in the same fashion that Hitler did in Germany. Together these leaders undertook an adventurous series of expansionist moves in Asia that eventually led to war with the United States.

Japan starts its own war by invading China

In 1931, Japan, coveting resources, invaded Manchuria, a province that belonged to China. The Chinese had difficulty defending Manchuria because China was behind the Japanese in weaponry, economics, and industry. Also, China was wracked with internal political differences that weakened Chinese military effectiveness. Thus, the Japanese easily conquered Manchuria against little resistance.

Six years later, in July 1937, the Japanese expanded this Sino-Japanese War dramatically by invading the rest of China. The Japanese army conquered major portions of the country, including the key seaports of Shanghai and Canton. Japanese troops generally behaved with ruthlessness and ferocity in an effort to cow the Chinese population into submission.

The main resistance to the Japanese came from the Nationalist Chinese (Kuomintang Party) and the Communist Chinese. The Kuomintang were pro-American and they controlled major portions of the country, but they were corrupt and, at times, militarily inept. The Communists were small in number but formidable and ruthless in battle. The Japanese knew they couldn’t hope to beat both of these groups and conquer the whole country. They simply wanted to control the most resource-rich portions of China while keeping their Chinese enemies at bay.

The U.S. drifts steadily toward war

Throughout the 1930s, most Americans disapproved of Japanese actions in China, but they weren’t willing to do anything about them. Mired in the Great Depression and disillusioned by the nation’s involvement in World War I, the American people wanted no part of any overseas war. President Roosevelt was much more concerned about Japanese actions than the average citizen, but he could do little in the face of such overwhelmingly isolationist sentiment. Indeed, in 1937, when Japanese planes sank an American gunboat in Chinese waters, killing three Americans, the American government settled for a half-hearted apology from the Japanese.

Roosevelt funneled small amounts of military and financial aid to the Chinese, but he was hampered by a series of neutrality laws Congress had passed between 1935 and 1937. These laws were designed to keep the United States out of future wars. They forbade Americans from selling arms to nations at war and also from traveling on their ships.

By 1940, after years of Japanese atrocities in China, relations between the United States and Japan were very tense. American public opinion was quite anti-Japanese, but very few people favored any sort of intervention in China. Still, the U.S. was preparing for war, just in case. The Roosevelt administration was now determined to rein in the Japanese. In a best-case scenario, the president hoped to force a Japanese withdrawal from China. But, at the very least, he wanted to prevent them from expanding anywhere else.

By 1940, after years of Japanese atrocities in China, relations between the United States and Japan were very tense. American public opinion was quite anti-Japanese, but very few people favored any sort of intervention in China. Still, the U.S. was preparing for war, just in case. The Roosevelt administration was now determined to rein in the Japanese. In a best-case scenario, the president hoped to force a Japanese withdrawal from China. But, at the very least, he wanted to prevent them from expanding anywhere else.

When the Germans conquered France, they left a pro-German government in place to govern France’s overseas colonies. This government, known as the Vichy French, was weak and could do little to defend France’s colonies in the southeast Asian countries of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Knowing this, the Japanese forced the Vichy French to allow them basing and transit rights in northern Vietnam. Deeply disturbed by this new Japanese expansion, the Roosevelt administration responded with a formal oil and steel embargo against Japan. From this point forward, the two nations began a steady drift toward war.

When the Germans conquered France, they left a pro-German government in place to govern France’s overseas colonies. This government, known as the Vichy French, was weak and could do little to defend France’s colonies in the southeast Asian countries of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Knowing this, the Japanese forced the Vichy French to allow them basing and transit rights in northern Vietnam. Deeply disturbed by this new Japanese expansion, the Roosevelt administration responded with a formal oil and steel embargo against Japan. From this point forward, the two nations began a steady drift toward war.

Failed negotiations

Roosevelt hoped that his combination of economic sanctions and diplomatic negotiations would force the Japanese to withdraw from China and abandon their plans for empire. The Japanese wanted to force the Americans to end the sanctions and accept Japan’s new empire as a reality. Throughout 1940 and 1941, diplomats from both countries held numerous talks, but they accomplished nothing. For either nation to back down would have meant humiliation. The Japanese were determined to upset the balance of power in Asia, and the United States would never agree to this change.

In July 1941, the Japanese took over all of Vietnam. In response, Roosevelt intensified the embargo, depriving Japan of 90 percent of its oil supply. He also froze Japanese assets in the U.S., a course of action that was one or two steps short of declaring war. The U.S. had now effectively pushed the Japanese into a corner. They could either give in to American wishes or they could go to war. Diplomatic negotiations continued throughout the fall of 1941 but, as before, they were totally unproductive.

The Japanese leadership — generals, politicians, and the emperor — held a fateful meeting on September 6, 1941. They decided that, if in two months the United States did not lift its embargo and retreat from its demands, Japan would go to war. They would then launch a daring series of surprise attacks on the Western nations, the most prominent of which would be an air attack against the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The Japanese plan was basic. They would attack the Dutch-controlled East Indies, British-controlled Malaya, the American-controlled Philippines, and Pearl Harbor all at the same time. In the process, the Japanese planned to deliver such devastating blows to the Western powers that they would be hopelessly crippled for the immediate future. Japan then hoped to negotiate peace with a wounded America that would presumably have little stomach for fighting its way across the Pacific in order to deny Japan its empire.

The Japanese leadership — generals, politicians, and the emperor — held a fateful meeting on September 6, 1941. They decided that, if in two months the United States did not lift its embargo and retreat from its demands, Japan would go to war. They would then launch a daring series of surprise attacks on the Western nations, the most prominent of which would be an air attack against the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The Japanese plan was basic. They would attack the Dutch-controlled East Indies, British-controlled Malaya, the American-controlled Philippines, and Pearl Harbor all at the same time. In the process, the Japanese planned to deliver such devastating blows to the Western powers that they would be hopelessly crippled for the immediate future. Japan then hoped to negotiate peace with a wounded America that would presumably have little stomach for fighting its way across the Pacific in order to deny Japan its empire.

Two months later, nothing had changed so, on November 25, the Japanese leaders decided to go to war and set their plan in motion. For America, World War II was about to begin.

Ever since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, conspiracy theorists have claimed that President Roosevelt knew of the Japanese plans and let them happen in order to mobilize public opinion for American entry into the war. Over the years, no less than half a dozen major books have made this claim, mostly on the basis of circumstantial evidence. Not one conspiracy advocate has ever produced any concrete proof of any conspiracy or any foreknowledge of Pearl Harbor on Roosevelt’s part. So what’s the verdict of history? In the view of most responsible military historians, Pearl Harbor resulted from American intelligence failures, not from any sort of conspiracy.

Ever since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, conspiracy theorists have claimed that President Roosevelt knew of the Japanese plans and let them happen in order to mobilize public opinion for American entry into the war. Over the years, no less than half a dozen major books have made this claim, mostly on the basis of circumstantial evidence. Not one conspiracy advocate has ever produced any concrete proof of any conspiracy or any foreknowledge of Pearl Harbor on Roosevelt’s part. So what’s the verdict of history? In the view of most responsible military historians, Pearl Harbor resulted from American intelligence failures, not from any sort of conspiracy.