Chapter 16

The Greatest War: World War II

In This Chapter

Fending off a Japanese onslaught

Turning the tide of the war

Liberating Europe

Island hopping to Japan

Coping on the home front

World War II was the biggest, most complex war the United States has ever fought, with Americans fighting all over the world, from remote South Pacific jungles to the North Atlantic. Winning the war required a total mobilization of American resources and manpower, affecting nearly everyone. Servicemen risked their lives in some of the bloodiest battles ever fought. On the home front, civilians experienced rationing and wartime shortages of such valued items as butter, gasoline, sugar, and tobacco. But the folks at home also enjoyed a booming economy. The country was united as never before or since.

The country was also unprepared for the war. For instance, in 1939, two years before the U.S. entered the war, the U.S. Army ranked behind the Romanian army in overall numbers. After Pearl Harbor, Americans began the painful process of mobilizing for war, learning how to fight a modern conflict, and standing up to the most powerful enemies the country had ever faced. Along the way, this massive war changed the country in ways no other event ever has.

In this chapter, I discuss the important battles, in both Europe and the Pacific. I explain what the battles were like, why they turned out the way they did, and their ultimate significance. Finally, I tell you how the war affected Americans at home. And if this chapter heightens your curiosity about the war, pick up World War II For Dummies by Keith D. Dickson (Wiley).

Bringing the War Home: Pearl Harbor

The morning of December 7, 1941, appeared to be like most other mornings at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, home to the U.S. Pacific Fleet. But under strict secrecy, a Japanese fleet of six aircraft carriers sailed to within 300 miles of the Hawaiian Islands. On that sleepy Sunday morning, the fleet launched its planes.

The first wave of these planes achieved complete surprise. In a matter of seconds, their bombs battered the USS Arizona. She rolled over and sank, ending the lives of more than 1,000 sailors and Marines. Elsewhere, Japanese planes hit and sank four other American battleships, plus numerous smaller vessels. They also destroyed 164 planes, mostly on the ground. By the time the Japanese onslaught finally subsided, 2,335 Americans were dead and another 1,178 wounded. The attack stunned the American people, but it brought them together as no other event could. The country now burned with war fever and a serious hankering for revenge against Japan.

Sixty-eight of the Americans who died in the Pearl Harbor attack were civilians. Some were killed by Japanese bomb shrapnel or machine gun bullets, but most were killed by American antiaircraft shells fired from the docked ships. As the shells exploded, their fragments cascaded onto land rather than into the open sea, killing the unfortunate bystanders.

Sixty-eight of the Americans who died in the Pearl Harbor attack were civilians. Some were killed by Japanese bomb shrapnel or machine gun bullets, but most were killed by American antiaircraft shells fired from the docked ships. As the shells exploded, their fragments cascaded onto land rather than into the open sea, killing the unfortunate bystanders.

When Japan decided to go to war with the U.S. and its allies, the Japanese planned to launch an all-out offensive in so many places that their enemies would be overwhelmed. They expected to conquer such a vast Pacific empire, along with the resources they coveted, such as oil and iron ore, that the U.S. would have to make peace rather than fight a ruinous, long war. So when the war started for America on December 7, 1941, Japanese planes, ships, and troops attacked in the following places:

British-controlled Hong Kong, Malaya, and Burma

The Dutch East Indies

New Guinea and the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific

Guam and Wake Island

The Philippines

The Gilbert and Marshall island chains

On December 8, President Franklin Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress. He denounced the Japanese for their surprise attack, referred to December 7 as a “date which will live in infamy,” and asked for a declaration of war. Congress was happy to oblige, turning in a nearly unanimous vote. The only dissenter was Congresswoman Jeanette Rankin, a pacifist isolationist from Montana.

A couple days later, Adolf Hitler, Germany’s head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces, declared war on the United States. Benito Mussolini, the Fascist Italian prime minister, soon followed. The U.S. was now part of a two-front war. Germany, Japan, and Italy headlined the Axis powers. The United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union led the Allies. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, Britain’s prime minister, agreed that, as the strongest of all the Axis powers, Germany must be defeated first. This was the primary Allied grand strategy vision of World War II.

In the final analysis, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a tactical success, but a strategic failure. Tactics have to do with how a war is fought; strategy encompasses why a war is fought (see Chapter 3 for more). The consequences of Pearl Harbor were:

The Japanese achieved complete surprise. They crippled the U.S. fleet but did not destroy it.

The Japanese failed to destroy the Navy’s submarine pens and fuel storage areas, as well as its aircraft carriers, which happened to be elsewhere on the day of the attack.

Pearl Harbor united the American people and ended isolationism (America’s preoccupation with domestic affairs at the expense of events overseas). A united America is a formidable America, and Americans were determined to win the war. The Japanese would not get their short war and negotiated settlement. Instead, Pearl Harbor guaranteed a long war that was more advantageous to the United States.

Early Battles in the Pacific

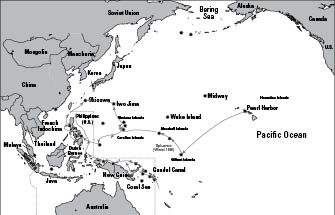

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Allies saw disaster after disaster during the first six months of the war in the Pacific. The Japanese were on the attack all over what is referred to as the Pacific Theater, from the Asian mainland to the South Pacific (as you can see in Figure 16-1). They even invaded and overran the Philippines. Not until the summer of 1942 did the Americans halt Japanese momentum and begin a slow turning of the tide.

Figure 16-1: Map of the Pacific Theater, 1942–1945.

The Philippines

Within a few hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese planes bombed the Philippines. Amphibious invaders soon followed. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the American commander in the Philippines, presided over a force that was unique in American history. Because the Philippines was an American colony, he controlled a mixed army of 100,000 Filipinos and 30,000 Americans. MacArthur had spent years building this army, and he was emotionally attached to it, as well as to the people of the Philippines.

Perhaps MacArthur’s emotions clouded his judgment. He thought his army could defend the coastlines against the Japanese invaders, but this coastal force failed utterly. The Japanese easily overran the poorly armed and trained Filipino soldiers. Even worse, the Japanese destroyed half of MacArthur’s air force on the ground in the first hours of the war, in spite of the fact that the general knew several hours before the Japanese attack that the U.S. had been drawn into war and such an attack was imminent. This was an inexcusable command screw-up on MacArthur’s part. From that point on, the enemy controlled the skies over the Philippines.

MacArthur finally managed to retreat with most of his army to the Bataan Peninsula where he hoped to hold out until help arrived from the States. But that help never came. At this stage, the unprepared U.S. was still staggering under the weight of multiple Japanese blows. For instance, the Navy, in the wake of Pearl Harbor, didn’t have the ships, planes, or manpower to save MacArthur. The awful reality was that his army was doomed. They were cut off from the outside world, living in the hills of Bataan, holding off the attacking Japanese. Allied soldiers existed on half rations, then quarter rations, and even ate monkeys and insects. Tropical diseases also ravaged the ranks.

The army did well to hold out until April 1942 when finally it could fight no more. By now, however, MacArthur was gone. Roosevelt, mostly for political reasons, ordered him out of the Philippines rather than see him end up a captive of the Japanese. The general escaped to Australia where he vowed, in his famous “I shall return” statement, to some day liberate the Philippines. In the meantime, the sad duty of surrendering the American-Filipino troops at Bataan and elsewhere in the Philippines fell to Maj. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright. “With profound regret and with continued pride in my gallant troops, I go to meet the Japanese commander,” Wainwright wrote to Roosevelt. “Good-bye, Mr. President.” About 80,000 American and Filipino troops surrendered, the largest single capitulation in American military history.

Coral Sea and Midway

After the Japanese conquered the Philippines, along with much of Asia and the central Pacific, they wanted to solidify the southern and eastern part of their new empire. This meant moving south toward Australia and east toward the Hawaiian Islands. In May 1942, a strong Japanese fleet moved into the Coral Sea, a body of water between Australia and New Guinea. The Japanese planned to take the southern coast of New Guinea and use it as a springboard to invade Australia.

After the Japanese conquered the Philippines, along with much of Asia and the central Pacific, they wanted to solidify the southern and eastern part of their new empire. This meant moving south toward Australia and east toward the Hawaiian Islands. In May 1942, a strong Japanese fleet moved into the Coral Sea, a body of water between Australia and New Guinea. The Japanese planned to take the southern coast of New Guinea and use it as a springboard to invade Australia.

The next month, they sailed an even more powerful fleet to the east, in the direction of the tiny American island base of Midway. The base was about 1,000 miles from Hawaii, close enough that if the Japanese could take Midway, their planes could then bomb Hawaii. These two Japanese thrusts provoked a pair of turning-point naval battles.

Battle in the South Pacific

At Coral Sea, a combined American and Australian fleet fought the Japanese to a standstill in the first great carrier battle in naval history. U.S. Adm. Chester Nimitz used top-secret intelligence, gleaned from broken Japanese codes, to put his forces in position. The American-Australian fleet and the Japanese fleet never actually spotted each other. Instead, carriers launched planes that sought out enemy ships and attacked them.

Almost all the fighting took place on one day, May 8, 1942. The Americans sank Shoho, a light aircraft carrier, and damaged another carrier. The Japanese had more success. They sank the USS Lexington and heavily damaged USS Yorktown, two of the most important carriers in United States’ fleet.

Although the Japanese had inflicted significant damage on Nimitz’s fleet, they were stunned by the ferocity of Allied resistance. The Japanese commander, Vice Adm. Shigeyoshi Inoue, decided to turn back rather than risk his ships to Allied land-based air attacks in the narrow waters south of New Guinea. Coral Sea was a costly but vital Allied strategic victory. The vital lifeline to Australia remained open.

Battle in the east Pacific

Battle in the east Pacific

At Midway, the Japanese amassed a powerful fleet of 145 warships, with a strike force of four major carriers in the lead. Once again, Nimitz’s intelligence specialists apprised him of Japanese intentions. Nimitz scraped together his three remaining carriers, including the hastily repaired Yorktown, and prepared for a decisive battle.

The fighting took place between June 4 and 7, but the decisive day was June 4, 1942. That day the battle began with a Japanese air raid on Midway. Not long after this, American planes found the Japanese fleet and attacked. The Japanese slaughtered the big, slow torpedo bombers. Out of 41 attacking U.S. planes, only six survived. Then the battle turned. In a matter of minutes, American dive bombers hit three enemy carriers, mortally wounding them. All three eventually sank. In a later attack, they sank the fourth Japanese carrier.

Late in the day on June 4, Japanese planes found the Yorktown and damaged her badly. An enemy submarine later finished her off. However, with such uneven losses, the Japanese could not hope to invade Midway. They retreated, never to return, having suffered one of the great defeats in naval history.

Midway turned the tide of the naval war in the Pacific. It bought the Americans vital time to rebuild their Navy and established relative naval parity between the U.S. and Japan.

New Guinea

MacArthur’s ultimate goal was a return to the Philippines. To do that, he needed to capture New Guinea as a steppingstone. In the summer of 1942, a combined army of Australian and American soldiers began a long, slow march from the south to the north coast of the island.

Conditions were beyond horrendous — jungles, swamps, mountains, insects, heat, disease, and the like. In December, at Buna and Gona, on the northern coast, the Allies ran into a strongly entrenched Japanese force that held out until well into January. At any given time, one-third of the American soldiers were down with malaria.

Conditions were beyond horrendous — jungles, swamps, mountains, insects, heat, disease, and the like. In December, at Buna and Gona, on the northern coast, the Allies ran into a strongly entrenched Japanese force that held out until well into January. At any given time, one-third of the American soldiers were down with malaria.

The fighting on the northern coast of New Guinea was a victory of sorts because the Allies had blunted the Japanese South Pacific advance. Nearly two more years of tough fighting lay ahead, though, as MacArthur’s forces leapfrogged their way along the coast, ever closer to the Philippines.

Guadalcanal

The other turning point came in the Solomon Islands. In July 1942, Allied intelligence discovered that the Japanese were building an airfield on the strategically important island of Guadalcanal. From here, Japanese planes and ships could menace Australia’s shipping lifeline to America. The Allies knew they had to take Guadalcanal or risk losing the war. On August 7, 1942, the 1st Marine Division invaded the island against only token resistance, seizing control of the valuable airfield. Realizing the vital importance of Guadalcanal, the Japanese soon reinforced it with strong air, land, and sea forces. The Americans did the same.

The battle turned into a dramatic struggle of wills. From August 1942 until early February 1943, the two sides fought desperately. The Japanese continually bombed the airfield, which the Americans had dubbed Henderson Field after a deceased Marine airman. Offshore, naval battles proliferated, so much so that the waters off Guadalcanal were known as Iron Bottom Sound because of all the sunken ships.

The worst fighting took place amid the jungles and swamps on the island itself. Marines and soldiers engaged in a daily contest for survival against well-trained, tenacious Japanese troops. For instance, the Japanese launched two major attacks in September and October aimed at capturing Henderson Field. They came out of the darkness in screaming human waves. The fighting was hand-to-hand, but the Americans held.

The worst fighting took place amid the jungles and swamps on the island itself. Marines and soldiers engaged in a daily contest for survival against well-trained, tenacious Japanese troops. For instance, the Japanese launched two major attacks in September and October aimed at capturing Henderson Field. They came out of the darkness in screaming human waves. The fighting was hand-to-hand, but the Americans held.

By February 1943, after six months of fighting, the Americans finally triumphed in this battle of attrition. The U.S. lost 1,768 soldiers killed in action, while the Japanese lost 24,600. Guadalcanal was the most important American victory in the first two years of the Pacific War.

Turning Attention to Europe

When the U.S. entered World War II on the Allied side in 1941, the Germans controlled nearly all of Europe, and they were well on the way to conquering the Soviet Union (see Figure 16-2). Without Soviet help, the western Allies could not hope to win the war in Europe. Hitler’s Germany was the most powerful of all the Axis nations and thus the most dangerous. He had to be defeated first, before he became too strong. So, in this war, the majority of American resources, supplies, and manpower went to Europe, while the Pacific usually received second priority.

Figure 16-2: Map of the European Theater, 1942–1945.

The Atlantic lifeline

The European Allies had to control the Atlantic. If they didn’t, then the United States could never project its manpower, weaponry, food, and industrial might overseas to Europe. The Germans could not compete with the Allies in surface ships, but their submarines were a powerful, potentially war-winning weapon. Churchill wrote that, during World War II, the German submarines (or U-boats) frightened him the most because they had the potential to marginalize the United States and strangle Great Britain into submission. They could do this by sinking more ships than the Allies could replace.

The European Allies had to control the Atlantic. If they didn’t, then the United States could never project its manpower, weaponry, food, and industrial might overseas to Europe. The Germans could not compete with the Allies in surface ships, but their submarines were a powerful, potentially war-winning weapon. Churchill wrote that, during World War II, the German submarines (or U-boats) frightened him the most because they had the potential to marginalize the United States and strangle Great Britain into submission. They could do this by sinking more ships than the Allies could replace.

Throughout the war, the enemy U-boats roamed the waters of the Atlantic, sometimes operating in packs, savaging vulnerable Allied merchant ships and warships alike. They sank hundreds of ships, some of them right off the east coast of the United States. The heyday for these enemy raiders was 1942–1943 when they sank nearly half a million tons of Allied ships and cargo per month. Had such German success continued, it’s likely that the Allies would have lost the war.

But, in the middle of 1943, the Allies began turning the tide in the struggle for their Atlantic lifeline. Using convoy tactics in which submarine-killing warships and airplanes escorted vulnerable merchant ships, the Allied navies sank more and more U-boats, to the point where German shipyards could no longer keep up with the losses. From this point on, the U-boats were more of a deadly nuisance than a mortal threat to America’s Atlantic lifeline.

The Allies employed three major weapons to neutralize the U-boats:

The Allies employed three major weapons to neutralize the U-boats:

Code-breaking: This was known as Ultra (short for Ultra-secret) intelligence. The British, and later the Americans, read some of the Germans’ secret military traffic during the war. This sometimes included information about the positioning of their submarines.

Escort carriers: These small aircraft carriers allowed the Allies to protect their convoys with continuous air cover.

Destroyers: These speedy, versatile ships were ideal submarine hunters and killers. Armed with excellent sonar and radar, along with depth charges (bombs that explode under water) and accurate, powerful, 5-inch guns, destroyers sank numerous U-boats.

Hitler’s misstep in Stalingrad

Hitler came tantalizingly close to victory over the Soviet Union in 1941, but failed (see Chapter 15 for details). In 1942, he was determined to succeed. He ordered a new offensive in southern Russia aimed at capturing the Caucasus oil fields and cutting the USSR in two. Starting in May 1942, the German army overran huge swaths of Russia and captured hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers.

However, in the fall, Hitler decided to refocus his offensive to capture Stalingrad, a city on the Volga River that was more of a political than strategic objective. The result was an urban battle that favored the Russians over the Germans. In several months of bitter urban combat, from September 1942 to February 1943, the Russians steadily turned the tide of battle in their favor. Eventually, they surrounded the Germans and compelled the surrender of about 100,000 freezing, starving survivors. Axis losses at Stalingrad were nearly 750,000 soldiers. This major Soviet victory changed the course of the war in the East. From here on out, the Germans found themselves — with only a few exceptions — fighting a defensive battle to hold what they had already conquered.

Invading North Africa

In the wake of Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, the average American in 1942 wanted to strike back at the Japanese, not the Germans. Thus, President Roosevelt’s Germany-first policy was not all that popular. Roosevelt wanted American soldiers in action against the Germans in 1942. He hoped that with U.S. troops fighting the Germans, the American people would inevitably warm to his Germany-first policy. Initially, Roosevelt and his generals wanted a cross-channel invasion of German-occupied France. The British believed, however, that the Allies were not yet ready for such an ambitious, complicated operation. They persuaded their eager American friends to focus on North Africa instead. For two years, the British had been fighting a seesaw war against an Italo-German army in Egypt (a British colony) and Libya (an Italian colony).

Together the Allies devised a plan. In Egypt, the British would launch an offensive aimed at pushing the Axis armies out of that colony for good. In the west, the Americans would lead an invasion of the Vichy French colonies Morocco and Algeria. The U.S. hoped the French would not fight. Even if they did, the two Allied armies, converging from the west and east, would catch the enemy armies in a vise, annihilate them, and secure the entire North African coast.

Together the Allies devised a plan. In Egypt, the British would launch an offensive aimed at pushing the Axis armies out of that colony for good. In the west, the Americans would lead an invasion of the Vichy French colonies Morocco and Algeria. The U.S. hoped the French would not fight. Even if they did, the two Allied armies, converging from the west and east, would catch the enemy armies in a vise, annihilate them, and secure the entire North African coast.

The American-led invasion was code-named Operation Torch. When the invasion force of 65,000 U.S. soldiers went ashore on November 8, 1942, they met with sharp resistance in some spots and little opposition in others. Most of the supposedly French soldiers were actually North African locals under the command of French officers. Some of these officers felt honor-bound to fight, yet few had any special hostility for the Americans. Others were actually eager to convert to the Allied cause. The fighting lasted for about a week and cost about 500 American lives before the Allied commander, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, negotiated a truce with Adm. Jean Darlan, the French commander. Many of Darlan’s soldiers joined the British and Americans to form a multinational army in North Africa.

In the weeks that followed, a dizzying series of events took place. Germany occupied the rest of France, ending the Vichy government’s existence. Darlan fell to an assassin’s bullet on December 24, 1942. The British kicked the Axis out of Egypt, ushering in a mobile campaign in Libya. The Americans raced for Tunisia, but a combination of bad roads, bad weather, lofty mountain peaks, and poor preparation hindered them. At the same time, Hitler decided to send substantial reinforcements, by air and sea, to Tunisia, where they constructed a formidable defensive line that stymied the Allies.

In the weeks that followed, a dizzying series of events took place. Germany occupied the rest of France, ending the Vichy government’s existence. Darlan fell to an assassin’s bullet on December 24, 1942. The British kicked the Axis out of Egypt, ushering in a mobile campaign in Libya. The Americans raced for Tunisia, but a combination of bad roads, bad weather, lofty mountain peaks, and poor preparation hindered them. At the same time, Hitler decided to send substantial reinforcements, by air and sea, to Tunisia, where they constructed a formidable defensive line that stymied the Allies.

Instead of a lightning victory in North Africa, the Allies were bogged down in a brutal campaign of attrition that raged through the winter of 1942–1943. Gradually, in early 1943, Allied air and sea attacks cut Axis supply lines to Tunisia. Steady ground attacks also increased the pressure. Finally, 275,000 Italian and German soldiers surrendered on May 10, 1943, securing North Africa for the Allies.

Taking Control of the War in Europe, 1943–1944

The Germans were definitely losing the war in Europe now. The tide had turned at such places as Stalingrad and El Alamein. The Germans were powerful and could still win the war, but time was not on their side. Each day the production and manpower capacity of the United States made the Allies stronger. Roosevelt and Churchill announced that hostilities would only cease with the Axis’s unconditional surrender, and Stalin concurred.

With North Africa in Allied hands, the question in 1943 was where to strike next. True to form, the gung-ho Americans favored an immediate cross-channel invasion of France. An invasion of France would allow the Allies to return to northern Europe, crush the German army, and overrun the Third Reich (a popular term for Hitler’s empire).

With North Africa in Allied hands, the question in 1943 was where to strike next. True to form, the gung-ho Americans favored an immediate cross-channel invasion of France. An invasion of France would allow the Allies to return to northern Europe, crush the German army, and overrun the Third Reich (a popular term for Hitler’s empire).

The British opposed invading France for the same reasons they had in 1942 — the Allies were not ready — and they were right. Among the western powers, only the U.S. had the potential power and resources to successfully accomplish these goals. In 1943, the U.S. was not quite ready for such a significant undertaking, though.

Referring to Italy as “the soft underbelly of the crocodile,” Churchill convinced Roosevelt to embark upon an invasion of what was perceived as the weakest of Axis nations. The Allies expected to knock Italy out of the war, thus getting into Europe through the back door.

Invading “the soft underbelly”: Sicily and Italy

The invasion of Sicily, code-named Operation Husky, was the second largest in the European war, behind only the Normandy invasion (see the section, “A great moment in history: The D-Day invasion at Normandy,” later in this chapter). The invasion force at Sicily consisted of 2,590 ships, hundreds of planes, and 180,000 troops. A mixed bag of Italian and German soldiers defended the island. Many of the Italians were heartily sick of the war and wanted only to surrender. By contrast, the Germans were more than eager to fight.

On July 10, 1943, the Allies struck. The British landed on the southeastern coast of Italy, near Syracuse. The Americans drew the mission of protecting the western flank of their British allies. Three American infantry divisions, the 45th, 1st, and 3rd, landed along a 30-mile front, between Cape Scaramia in the east and Licata in the west. Both the British and the Americans dropped highly trained paratroopers behind the targeted beachheads to secure bridges and harass enemy reinforcements.

Although the landings were a success, the campaign that followed was long and difficult. The British ran into strong German reinforcements around Mount Etna, a peak that dominates the entire eastern half of the island. The Americans also dealt with tough resistance that slowed their advance. It took the Allies five weeks, and almost 24,000 casualties, to secure Sicily. By that time, many of the German soldiers had escaped to fight again another day.

For the Americans, the highlight of the Sicily campaign was the 3rd Division’s epic march from the southern to the northern coast. The division commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, had trained his men to march long distances in all kinds of weather at a very brisk pace. The men, who were lean, tough, and resilient, called this the “Truscott Trot.” Marching in summer heat, through mountainous terrain, they covered 90 miles in three days and took Palermo, one of the main objectives.

For the Americans, the highlight of the Sicily campaign was the 3rd Division’s epic march from the southern to the northern coast. The division commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, had trained his men to march long distances in all kinds of weather at a very brisk pace. The men, who were lean, tough, and resilient, called this the “Truscott Trot.” Marching in summer heat, through mountainous terrain, they covered 90 miles in three days and took Palermo, one of the main objectives.

With Sicily in hand, the Allies invaded the Italian mainland. By now, Mussolini had fallen from power. The new Italian government secretly negotiated with Gen. Eisenhower to get Italy out of the war. By the time an Anglo-American invasion force went ashore at Salerno on September 9, 1943, Italy had surrendered. The Germans anticipated this whole scenario and simply took over Italy as another occupied country. For Allied soldiers, the occupation meant they were now facing hard-core German soldiers instead of disinterested, war-weary Italian troops.

Over the course of the next two years, the Allies slowly slugged their way up the Italian boot, against fierce resistance, often in terrible weather and mountainous terrain. Far from being a “soft underbelly,” as Churchill believed, Italy was a dead end. Only two real positives came out of the Italian campaign:

The liberation of Rome on June 4, 1944

The capture of air bases from which to bomb Hitler’s Europe

A great moment in history: The D-Day invasion at Normandy

In the summer of 1944, the Allies were finally ready to invade France. They chose to do so at Normandy on June 6, 1944. The invasion armada consisted of 6,900 ships, with 12,000 aircraft protecting them overhead. More than six divisions, totaling some 90,000 troops, carried out the initial amphibious assault.

The British and Canadians invaded at three code-named beaches — Gold, Juno, and Sword. The Americans went ashore at beaches code-named Utah and Omaha. Three divisions of paratroopers and glider soldiers descended from the nighttime Norman skies to cover the flanks of the invasion. The American paratroopers were scattered all over the Cotentin Peninsula, behind Utah beach. They fought in small groups, hindering the German response to the invasion.

For the Americans, the biggest crisis on D-Day (the day on which the invasion occurred) happened at Omaha beach. The sloping, rocky bluffs that overlooked the beach were ideal for defenders. Elements of a first-rate German division — soldiers from Hanover — expertly defended the beach. When the Americans came ashore, they ran into a firestorm of machine gun, rifle, mortar, and artillery fire, plus mines. American soldiers had their heads blown off and their arms, legs, and torsos shattered. The waters ran red with blood. Through sheer courage and tenacity, the Americans prevailed. The film Saving Private Ryan graphically and accurately portrays the western edge of Omaha beach on D-Day morning.

For the Americans, the biggest crisis on D-Day (the day on which the invasion occurred) happened at Omaha beach. The sloping, rocky bluffs that overlooked the beach were ideal for defenders. Elements of a first-rate German division — soldiers from Hanover — expertly defended the beach. When the Americans came ashore, they ran into a firestorm of machine gun, rifle, mortar, and artillery fire, plus mines. American soldiers had their heads blown off and their arms, legs, and torsos shattered. The waters ran red with blood. Through sheer courage and tenacity, the Americans prevailed. The film Saving Private Ryan graphically and accurately portrays the western edge of Omaha beach on D-Day morning.

The invasion was the culmination of years of planning, and it was a major success. By the end of D-Day, the Allies were firmly ashore in France. For the Americans, the invasion signaled the beginning of superpower status and world leadership. The operation and the campaign that followed could never have happened without American leadership. For instance, over the next year, as the Allies fought to defeat Germany in northern Europe, two-thirds of their supplies, manpower, and weapons were American. This foreshadowed the American world leadership that would follow the war.

The invasion was the culmination of years of planning, and it was a major success. By the end of D-Day, the Allies were firmly ashore in France. For the Americans, the invasion signaled the beginning of superpower status and world leadership. The operation and the campaign that followed could never have happened without American leadership. For instance, over the next year, as the Allies fought to defeat Germany in northern Europe, two-thirds of their supplies, manpower, and weapons were American. This foreshadowed the American world leadership that would follow the war.

Liberating France

As successful as the Normandy invasion was, it didn’t guarantee victory. It was actually only the first step in a long, bloody campaign to defeat Germany. In the weeks that followed D-Day, the Germans sent large numbers of reinforcements to Normandy and held the Allied armies in a stalemate (or deadlock). Throughout the summer of 1944, the two sides grappled in a terrible death struggle amid the hedgerows of Normandy. Not until August did the Allies rip through the German lines, break the stalemate, and send Hitler’s soldiers into headlong retreat.

On August 25, 1944, French and American soldiers liberated Paris. Raucous celebrations and a parade soon followed. Thousands of American soldiers took a break from the fighting to parade down the Champs-Elysees. Some even found French girlfriends, if only for a night or two.

Elsewhere, the Germans were retreating back to their own country as fast as their legs or vehicles could carry them. In early September, advanced American patrols even crossed the border into Germany. The Allied world buzzed with optimistic talk about the war being over by Christmas, but this didn’t happen. Instead, the Germans rallied and set up strong defenses along their western borders. At the same time, the Allies ran into serious supply problems that would plague them for the rest of the war and impede their momentum.

Gambling in Holland

On September 17, 1944, the Allies unleashed a bold gamble designed to win the war in 1944. They dropped three airborne divisions behind enemy lines in Holland — the 101st Airborne at Eindhoven, the 82nd Airborne at Nijmegen, and the British 1st Airborne at Arnhem. Their job was to secure Highway 69 (soon dubbed “Hell’s Highway” by the GIs), along with a key series of bridges, including the Arnhem bridge that led over the Rhine. In the next phase of the operation, the British XXX Corps, bristling with tanks, was to hook up with the paratroopers and then drive across the Rhine into Berlin and win the war. The code name for the operation was Operation Market-Garden.

On September 17, 1944, the Allies unleashed a bold gamble designed to win the war in 1944. They dropped three airborne divisions behind enemy lines in Holland — the 101st Airborne at Eindhoven, the 82nd Airborne at Nijmegen, and the British 1st Airborne at Arnhem. Their job was to secure Highway 69 (soon dubbed “Hell’s Highway” by the GIs), along with a key series of bridges, including the Arnhem bridge that led over the Rhine. In the next phase of the operation, the British XXX Corps, bristling with tanks, was to hook up with the paratroopers and then drive across the Rhine into Berlin and win the war. The code name for the operation was Operation Market-Garden.

The plan soon went awry. German resistance was much more potent than Allied intelligence officers had estimated. In fact, the British landed right in the midst of elite Nazi SS armored units. These Germans annihilated the British 1st Airborne Division. The Americans lost 3,664 killed in action. In the end, the Allies gained some ground but failed to cross the Rhine into Germany. They instead endured a rainy stalemate in Holland that fall.

Kaput! The End for Hitler and His Cronies

Hitler’s Reich was strong enough to hold out for the rest of 1944, but defeat was now inevitable. Germany was surrounded on all sides. The western Allies were preparing to breach Germany’s western borders while the Soviets were doing the same in the east. Germany was running low on fuel and manpower. Allied fighters and bombers, in a round-the-clock offensive, had swept German planes from the skies. Hitler himself was in bad shape. He had survived an assassination attempt in July 1944 that left him shaky and frail. Like a cornered but dangerous animal, he decided to lash out one more time.

The Battle of the Bulge

On December 16, 1944, Hitler gambled everything in one last-ditch offensive. Under the cover of bad winter weather that negated Allied air power, 300,000 German soldiers attacked the American lines along a thinly held, 80-mile sector in the Ardennes Forest. These forces included Germany’s best remaining armored formations. The German objective was to cross the Meuse River, capture Antwerp, Belgium, the most vital supply port in northern Europe, and split the Allied armies in two. Hitler hoped he could negotiate an end to hostilities in the West at that point and turn his full attention to fighting the Russians in the East.

Hitler’s plan was heavily dependent on surprise, which he achieved, but also speed. Although the Americans were shocked by the bold offensive, they fought well. Small, isolated groups fought ferociously, costing the Germans valuable time, men, and equipment. The Germans drove a bulge in the American lines — earning the battle its famous nickname, “Battle of the Bulge” — but never even crossed the Meuse. By Christmastime, the attack had lost all momentum, and American reinforcements had begun to turn the tide. The Americans spent the next month on the offensive, recapturing the Ardennes ground they had lost, all in bitterly cold winter weather.

The Bulge was the second-costliest battle in U.S. military history, behind only the Argonne Forest in World War I (see Chapter 14). In the Bulge, the Americans suffered nearly 90,000 casualties: 19,276 killed, 23,218 captured or missing in action, and more than 47,000 wounded.

Invading Germany

With the failure of his Ardennes offensive, and another lesser one in Lorraine, Hitler’s defeat was now just a matter of time. In the early months of 1945, Allied armies, from east and west, overran Germany. The fighting was fierce. In fact, American casualty rates were on par with the bloodlettings they had suffered in the fall of 1944. But victory was imminent. Hitler took to his Berlin bunker. On April 30, 1945, with Soviet troops only a few blocks away, Hitler took his own life. Nazi Germany unconditionally surrendered a week later on May 7, 1945.

As Allied soldiers conquered Germany, they liberated hundreds of concentration camps, thus discovering the terrible results of Nazi tyranny. The emaciated, diseased survivors of these camps greeted their liberators with tears and hugs. In all, the Nazi Germany regime killed 10 million people, including 6 million Jews, through a systematic policy of cruelty, exploitation, and genocide. This is generally known as the Holocaust.

For the Americans, the greatest prize in Germany was to capture Hitler’s lavish alpine home in Berchtesgaden. In the war’s final days, many units were vying to get there first. Because of a mistake in the book and miniseries Band of Brothers, most Americans believe that the 101st Airborne Division was the first unit into Hitler’s home. In reality, the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Infantry Division got there first, at roughly 4 p.m. on May 4, well before the paratroopers ever reached the area.

For the Americans, the greatest prize in Germany was to capture Hitler’s lavish alpine home in Berchtesgaden. In the war’s final days, many units were vying to get there first. Because of a mistake in the book and miniseries Band of Brothers, most Americans believe that the 101st Airborne Division was the first unit into Hitler’s home. In reality, the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Infantry Division got there first, at roughly 4 p.m. on May 4, well before the paratroopers ever reached the area.

Island Hopping in the Pacific

On the Pacific front, throughout 1943 and early 1944, the Americans gradually ate away at the Japanese empire by island hopping. In other words, they chose several Japanese-held islands to assault, outflanked others, and left their garrisons (or troops) to starve. The most intense of these selective invasions took place at tiny Tarawa, where 4,500 Japanese soldiers mostly fought to the death in three brutal days of combat November 20–23, 1943. The battle cost the 2nd Marine Division 1,009 men killed.

In 1944, hard-earned victories like Tarawa put the Americans in a position to pierce the inner ring of Japanese defenses. Gen. MacArthur, who was finishing up a long campaign in New Guinea, focused on liberating the Philippines. In the meantime, Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet, planned to liberate the Mariana Islands.

Invading the Marianas

Nimitz made his first move at the Japanese colony of Saipan, on June 15, 1944, when two divisions of U.S. Marines hit the beach. Japanese resistance was desperate, even fanatical. The Japanese carried out banzai (suicide) attacks on foot, emerging from the cover of darkness, screaming and hurling themselves at the Americans, attempting to bayonet Marines in their foxholes. The Americans held fast and slaughtered the Japanese in droves. A combined force of soldiers and Marines needed a little over three weeks to capture the island. Rather than surrender, some of the Japanese hurled themselves off cliffs into the sea or blew themselves up with grenades. In July and August, at Guam and Tinian, the Japanese fought with similar ferocity, but lost in the end.

Meanwhile, at sea, Nimitz’s fleet won a great victory. In two days of fighting on June 19–20, 1944, the Americans sank three Japanese aircraft carriers and shot down 600 planes. The U.S. Navy lost 123 planes, mostly because aviators ran out of fuel and had to ditch them into the Philippine Sea. The vast majority of the American fliers survived. This naval battle was so one-sided that the Americans called it “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” The official name of the battle, though, is the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

The Marianas campaign was the pivotal moment of the Pacific War. With the Marianas under control, the U.S., for the first time, had ideal bases from which to bomb Japan. They had breached the vital inner ring of Japanese defenses and could now use the Marianas as a perfect jumping-off point for a final push on Japan itself. The Marianas campaign was to the Pacific War what Normandy was to the war in Europe — a vital pivot point that decided the outcome of the war. (See “A great moment in history: The D-Day invasion at Normandy” earlier in the chapter for more about the Normandy invasion.)

The Marianas campaign was the pivotal moment of the Pacific War. With the Marianas under control, the U.S., for the first time, had ideal bases from which to bomb Japan. They had breached the vital inner ring of Japanese defenses and could now use the Marianas as a perfect jumping-off point for a final push on Japan itself. The Marianas campaign was to the Pacific War what Normandy was to the war in Europe — a vital pivot point that decided the outcome of the war. (See “A great moment in history: The D-Day invasion at Normandy” earlier in the chapter for more about the Normandy invasion.)

Returning to the Philippines

On October 20, 1944, Gen. MacArthur’s forces finally returned to his beloved Philippines with an invasion of Leyte. The campaign on land was a deadly slugging match. The Americans fought two months before liberating the island. They killed 49,000 Japanese soldiers and suffered about 15,000 casualties.

At sea, the two sides fought the largest naval battle in modern history. The Japanese converged on Leyte with two major fleets, nearly overwhelming the American fleet and mauling the invasion beaches. However, the U.S. Navy battled them to a bloody standstill. In the end, the Japanese failed in their mission to thwart the invasion. From now on, the U.S. Navy controlled the waters around the Philippines. Realizing this, the Japanese began launching suicide kamikaze attacks by deliberately crashing their planes onto the American ships.

MacArthur followed up the Leyte operation with an invasion of Luzon, the main island. There, and at other smaller islands throughout the archipelago, his troops fought some 380,000 Japanese soldiers under the command of Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita. The Japanese commander sprinkled his die-hard soldiers throughout the Philippines’s rugged mountains and ridges, forcing MacArthur to come to him. The result was a slow, costly campaign of attrition. The worst fighting took place in Manila, where elements of three American divisions liberated the city in close-quarter, intense urban combat.

MacArthur liberated most of the Philippines but never completely defeated Yamashita in the Philippines, because Yamashita was still holding out at the end of the war. American losses were considerable. One out of every three American casualties in the Pacific War occurred in the Philippines campaign of 1944–1945.

A Horrible Climax: The Close of the War

The Pacific War became progressively worse with every American victory as the Japanese grew more desperate. After the Americans took the Philippines and the Marianas, their next move was to take some final steppingstones to Japan and then the home islands themselves. Japanese resolve did not falter. They were determined to inflict such terrible losses on the Americans that the U.S. would make peace before winning a total victory in this war.

Destruction from above and at sea

By the end of 1944, the United States was employing two major weapons to bring Japan to its knees: airpower and sea power. On November 24, 1944, America’s newest heavy bombers, B-29s, began flying missions from the Marianas to bomb Japan. At the same time, American submarines were sailing in the waters off China and around Japan, inflicting catastrophic damage to Japanese shipping. Together these air and sea attacks crippled Japanese industry, resources, shipping, and mobility.

The Air Force started out by bombing very specific targets in Japan, but soon gave this tactic up in favor of all-out raids:

Beginning in late February 1945, the B-29s flew low-altitude, fire-bombing raids on Japan’s cities. These were devastating because traditional Japanese construction employed heavy use of paper and wood as opposed to concrete and steel.

These raids killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and rendered millions of others homeless in such cities as Tokyo, Nagoya, Kawasaki, and Yokohama.

By mid-summer of 1945, the bombers were running out of worthwhile targets.

The U.S. also waged successful sea attacks against Japan. Armed with new-generation boats and torpedoes, U.S. submariners achieved in the Pacific what German subs attempted to accomplish against the United States in the Atlantic — they destroyed Japan’s economy.

By the middle of 1945, American subs had sunk two-thirds of Japan’s oil tankers and nearly her entire merchant fleet — 3 million tons of ships in all.

Submariners comprised only 1.6 percent of the Navy, but sank, in Europe and the Pacific, 5.3 million tons of enemy ships and cargo, including eight carriers.

Overall, in both theaters, the Navy lost 52 subs during the war and 3,505 submarine sailors, a 22 percent casualty rate.

The atomic end of the war

In 1945, the Americans fought climactic battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, Japan. As usual, the Japanese fought to the finish. Iwo Jima was the costliest battle in the history of the Marine Corps, ending the lives of more than 5,000 Marines. At Okinawa, the Japanese turned the kamikaze attack into a veritable art form, sinking 38 ships and killing more than 5,000 American sailors. In spite of these devastating losses, the Americans prevailed in both battles and were on the doorstep to Japan. U.S. commanders planned for an invasion of Kyushu in November 1945, to be followed by an all-out assault on Honshu in March 1946.

In recent years, historians have begun to debate whether the invasion of Iwo Jima was necessary. The main reasons commanders gave for the invasion was to win an emergency landing field for B-29 crewmen and eliminate a significant Japanese airbase that was a thorn in the side to the bombers. For years, World War II historians bought this argument, assuming that, though Iwo was costly, it saved the lives of many airmen. However, recent research, especially a book by a Marine captain named Robert Burrell, has shown otherwise, prompting a lively and emotional debate.

In recent years, historians have begun to debate whether the invasion of Iwo Jima was necessary. The main reasons commanders gave for the invasion was to win an emergency landing field for B-29 crewmen and eliminate a significant Japanese airbase that was a thorn in the side to the bombers. For years, World War II historians bought this argument, assuming that, though Iwo was costly, it saved the lives of many airmen. However, recent research, especially a book by a Marine captain named Robert Burrell, has shown otherwise, prompting a lively and emotional debate.

On July 20, 1945, the United States became the world’s first nuclear power with a successful atomic bomb test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. President Harry S. Truman, who had succeeded FDR upon the latter’s death, decided to use the new weapon against Japan. Truman was hoping to forestall a costly invasion. He viewed the atomic bomb as simply another weapon in the strategic bombing campaign against Japan.

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, an American bomber dropped another one on Nagasaki. Both of these bombings inflicted serious damage and hundreds of thousands of casualties. In the wake of this nuclear onslaught, the Japanese surrendered on August 14, 1945, ending the greatest of all wars. The war cost the lives of 62 million human beings.

Life on the Home Front

World War II profoundly affected the American people and led to significant changes in the country. Americans were unified as never before or since. Nearly everyone agreed that the war needed to be fought and won. Most Americans, from the very young to the very old, wanted to do their part to win the war:

Children collected scrap metal for war industries.

Housewives donated blood.

Older men served as air raid wardens.

Young men volunteered for the military in droves.

Mobilizing for war

The United States transitioned to a wartime economy, creating 17 million war-related jobs, many of which went to women and African Americans. Unemployment declined dramatically, to less than 2 percent. The government doled out healthy profits to industries for producing war materiel. A large government agency, the War Production Board, allocated raw materials, oversaw production of civilian and military items, and distributed defense contracts. Hundreds of other agencies dealt with everything from price controls to weapons research and housing shortages. The results of this mobilization were dramatic:

The United States produced more war materiel than all the Axis nations combined.

American shipyards constructed more than 90,000 ships.

45 percent of the federal budget went to defense.

So how did we pay for all of this? Federal income taxes were very high, up to 90 percent in some cases. The government sold low-interest, secure war bonds to finance its wartime spending. Bankers loaned Uncle Sam money. When all that was still not enough, the government embraced deficit spending (spending more money than you bring in). The budget deficit was $259 billion by 1945.

Changing the face of society

Unlike the citizens of most World War II belligerents, Americans lived in a secure environment, free of bombings, combat, or even serious deprivation. Rationing, a limit placed on how much a person could purchase of certain products, was one of the most obvious ways the war affected average people. The needs of the war fronts, combined with a decline in the availability of consumer goods, produced shortages. The government mandated strict rationing of such valued items as nylon stockings (because nylon could be used to make a range of military items), eggs, butter, tobacco, and gasoline.

Americans were constantly on the move during the war years. Young men left home and entered military service. Six million women entered the workplace, sometimes in traditionally male jobs like shipbuilding or welding. In the process, these working women traveled the country and achieved some level of economic independence, thus challenging the accepted gender role of women as homemakers. The West Coast grew exponentially. For instance, 2 million people moved to California during the war. Six million Americans, attracted by wartime jobs, left farms to go to cities. African Americans migrated from the South to the upper Midwest and the West Coast.

All of this mobility led to dramatic changes in America. Sun Belt states like California, Arizona, and Florida rose in population and importance. The national economy that grew from the war was the strongest in world history. African Americans yearned for racial justice and equality in a country where segregation and second-class status for “coloreds” was often the norm. As black Americans migrated all over the country, race became a national issue, not just a southern concern. Thus, a major civil rights movement grew out of World War II.

Racial injustice was a serious problem in wartime America. In 1943, in Detroit, tension between blacks and whites boiled over into riots that cost the lives of 34 people. Harlem, New York, also experienced race riots, as did numerous military bases in the South. In Los Angeles, white servicemen clashed with Latino youths in what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots. The federal government was worried that Japanese Americans would spy for Japan, so troops rounded them up and placed them in internment camps during the war. Many Japanese Americans lost homes and property, not to mention civil liberties.

Racial injustice was a serious problem in wartime America. In 1943, in Detroit, tension between blacks and whites boiled over into riots that cost the lives of 34 people. Harlem, New York, also experienced race riots, as did numerous military bases in the South. In Los Angeles, white servicemen clashed with Latino youths in what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots. The federal government was worried that Japanese Americans would spy for Japan, so troops rounded them up and placed them in internment camps during the war. Many Japanese Americans lost homes and property, not to mention civil liberties.

About 900,000 African Americans served in the military in World War II. At that time, the armed forces were still segregated, a bitter irony while the U.S. was fighting such intensely racist regimes. The vast majority of black servicemen worked in noncombat jobs under white officers. During the war, it was not at all unusual for whites-only restaurants to feed German and Italian POWs (on lunch breaks from paying jobs outside their camps) but turn away black servicemen.

About 900,000 African Americans served in the military in World War II. At that time, the armed forces were still segregated, a bitter irony while the U.S. was fighting such intensely racist regimes. The vast majority of black servicemen worked in noncombat jobs under white officers. During the war, it was not at all unusual for whites-only restaurants to feed German and Italian POWs (on lunch breaks from paying jobs outside their camps) but turn away black servicemen.