Chapter 18

Hot War in Asia: The Korean War

In This Chapter

Containing the North Korean onslaught

Crossing the 38th parallel

Dealing with a wider war

Negotiating a status quo ending

A significant consequence of World War II was the disintegration of colonial empires, such as the Imperial Japanese empire. Between 1904 and 1945, the Japanese controlled Korea, a peninsular country in east Asia. With Japan’s defeat, Soviet and American troops occupied Korea with the Soviets in the north, above the 38th parallel, and the Americans below it in the south. Their job was to disarm the Japanese and then, together, create a new Korea.

However, as the Cold War (a period of intense conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union without actual warfare; see Chapter 17 for more) solidified between 1945 and 1949, the ensuing tension between the Soviets and the Americans led to the creation of two Koreas:

North Korea was a hard-line Communist state in the Russian model.

South Korea was a non-Communist, but not necessarily democratic state that emerged under American support.

In 1949, when Communists under Mao Tse-tung won power in China after several years of civil war, Cold War tensions in Korea grew even worse. By 1950, Soviet and U.S. troops were gone. Both Koreas wanted to unite the peninsula under their control. That summer, when the Communist North attempted to do just that, President Harry Truman decided to send American troops to stop them and save South Korea from Communism. This was the beginning of a three-year war fought from 1950 to 1953 that claimed more than 33,000 American lives.

In this chapter, I outline why the war happened and give you a feel for how close the North Koreans came to winning in 1950. I describe the seesaw battles of 1950–1951 and explain the overriding politics that dictated much of what happened on the battlefield. Finally, I cover how, why, and when the war ended, and provide you with a sense of its enduring legacy that still affects us today.

Conspiring for Conquest in Korea

In 1949, Kim Il-Sung, the Communist leader of North Korea, conceived of a plan to conquer South Korea. To go forward with his plan, he needed Chinese and Soviet approval because he would be dependent upon these two premier Communist nations for supplies and protection in case the U.S. intervened in Korea.

Contrasting Koreas

The two Koreas were a study in contrasts. The North was clearly stronger than the South. This imbalance was what prompted Kim Il-Sung to contemplate his invasion in the first place. Needless to say, comparing the two Koreas’ military and geopolitical strength did not bode well for South Korea:

North Korea had

A hard-line, absolutist, Communist regime in total control of the country

Control of most of Korea’s industry and water resources

A well-trained army of 133,000 soldiers, many of whom had fought in the Chinese civil war

Soviet-made tanks, artillery, warplanes, and small arms

South Korea had

A shaky, repressive, non-Communist government, headed by Syngman Rhee, an aged former political exile who had won a mildly corrupt election in 1948.

An insurgent Communist movement that used terrorism in an attempt to overthrow Rhee.

Very little industry or natural resources.

An army of 95,000 militia soldiers who were poorly armed, poorly trained, and were not prepared for conventional warfare. They had almost no American military support.

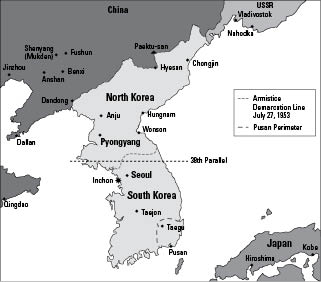

By April 1950, after months of secret meetings with the Russians and Chinese, Kim Il-Sung had secured the approval of his two Communist allies to invade South Korea. The Soviets would supply him with weapons and technology, while the Chinese planned to send troops. On June 25, 1950, North Korean troops and tanks crashed across the border into South Korea (see Figure 18-1). The Korean War had begun.

Figure 18-1: Map of the Korean War, 1950–1953.

Slicing into the South

Not surprisingly, when the North Koreans invaded in June 1950, they sliced through South Korean defenders like the proverbial hot knife through butter. They captured Seoul, the South Korean capital, in three days. They continued their advance along the three major north–south roads that spanned South Korea. South Korean resistance was spotty at best. Wherever the South Koreans did resist, their North Korean enemies crushed them.

At this point, the South had nothing with which to hold back the North Korean juggernaut. The Rhee government fled south, rather than surrender. Their days were clearly numbered, though, unless they received help from the United States.

Getting U.S. and UN Political Ducks in a Row

President Truman believed that the United States must contain Communism wherever it threatened to spread. He knew that the American people were deeply worried about the threat of Communism to America’s security and liberty. Indeed, as committed as he was to opposing the Communists, some of his political opponents, such as Sen. Joseph McCarthy, repeatedly accused him of being too soft on Communism. Thus, when he heard about the North Korean invasion of South Korea, he felt strongly that the United States must intervene. He immediately ordered American troops, planes, and ships to Korea. Congress overwhelmingly supported this decision.

Stemming the tide of Communism

The ironic thing about Truman’s commitment to the war in Korea is that most American policymakers didn’t consider the country to be of vital interest to the United States. Truman’s secretary of state, Dean Acheson, had even given a highly publicized speech in January 1950 omitting Korea from the Asian/Pacific countries America planned to defend in the event of Communist aggression.

So why the change of heart? Two reasons:

The United States was committed to a policy of containment of Communism, no matter where it threatened to spread.

Truman and other American leaders were convinced — correctly as it turned out — that the North Koreans could never invade South Korea without Soviet and Chinese approval.

Truman and his advisors feared that, if the United States did nothing in Korea, their inaction would embolden other Communist invasions, perhaps against western Europe or Japan.

Calling on the UN

At the end of World War II, the Allies had created the United Nations (UN) as a world peacekeeping body that would enforce collective security. President Truman was determined to enlist the support of the UN to check North Korean aggression.

Working with his allies, Truman succeeded in getting the UN to adopt a resolution that mandated North Korean withdrawal from South Korea. Under the mandate, multinational military forces would be deployed to Korea, fight together with UN support, eject the North Koreans from South Korea, and restore the prewar status quo. Eventually, 16 non-Communist countries sent troops to fight in Korea, including Turkey, Greece, Philippines, Canada, Britain, Belgium, Luxembourg, and, of course, the United States.

The United States succeeded in winning UN approval to intercede in Korea partially because of a stroke of luck. The Soviet Union was absent from the proceedings of the powerful UN Security Council whose approval was necessary for UN troops to be sent to South Korea. The council consisted of five permanent members: the U.S., Britain, France, China, and the Soviet Union. In late June 1950, the Soviets were boycotting the Security Council meetings because the non-Communist countries on the council had not allowed the new Communist Chinese government to assume control of that country’s council seat. The Soviet Union’s absence was a lucky break for Truman and a bad mistake by the Soviets.

The United States succeeded in winning UN approval to intercede in Korea partially because of a stroke of luck. The Soviet Union was absent from the proceedings of the powerful UN Security Council whose approval was necessary for UN troops to be sent to South Korea. The council consisted of five permanent members: the U.S., Britain, France, China, and the Soviet Union. In late June 1950, the Soviets were boycotting the Security Council meetings because the non-Communist countries on the council had not allowed the new Communist Chinese government to assume control of that country’s council seat. The Soviet Union’s absence was a lucky break for Truman and a bad mistake by the Soviets.

Implementing NSC-68

The war in Korea created a favorable political climate for Truman to implement a National Security Council policy paper called NSC-68. The paper was the product of a top-secret meeting of Truman’s national security team in January 1950. At the meeting, the team analyzed the Soviet and Chinese threat in dire terms. To counter the growing threat, they called for three major courses of action:

The U.S. and its allies had to begin an immediate conventional military buildup.

For containment to succeed, the United States should now assume the defense of the non-Communist world.

These new defense responsibilities would mean spending between $35 billion and $50 billion per year and 20 percent of the gross domestic product on national defense.

The authors of NSC-68 envisioned a new military draft and higher taxes to support their program. Truman agreed with NSC-68. However, he knew it would be controversial because of its call for larger armed forces, more military spending, and higher taxes. So he kept the plan secret until the North Korean invasion created a more receptive political environment. From that point on, one of Truman’s key wartime objectives was to implement NSC-68.

Clashing with the Titans

The United States was ill-prepared to fight in Korea. The closest American ground combat formations were on occupation duty in Japan. These units were undermanned, ill-equipped, and poorly trained for war. Nonetheless, the desperate circumstances in Korea meant that these men had to be thrown into battle against the North Koreans. Throughout the summer of 1950, these Americans, along with their hard-pressed South Korean allies, clung to a small perimeter, anchored by their main supply port of Pusan. This little perimeter was all that stood between the North Koreans and the total conquest of South Korea. Day after day, the North Koreans attacked, putting maximum pressure on their enemies before reinforcements could arrive to help them.

Holding the Pusan Perimeter

For the unfortunate American soldiers in the Pusan Perimeter, the summer of 1950 was a terrifying, difficult time. They had little tank support. They were not in good enough physical condition to deal with the suffocating heat. Their weapons were inferior to the Communist weapons. Some of the Americans had never even been trained to fire their weapons, particularly the recoilless rifles that were their only defense against North Korean tanks. Numerous American soldiers died because they couldn’t figure out how to use the weapon against enemy tanks. By August 1, American ground forces had suffered more than 6,000 casualties, including 901 taken prisoner. The North Koreans simply executed many of their American captives.

For the unfortunate American soldiers in the Pusan Perimeter, the summer of 1950 was a terrifying, difficult time. They had little tank support. They were not in good enough physical condition to deal with the suffocating heat. Their weapons were inferior to the Communist weapons. Some of the Americans had never even been trained to fire their weapons, particularly the recoilless rifles that were their only defense against North Korean tanks. Numerous American soldiers died because they couldn’t figure out how to use the weapon against enemy tanks. By August 1, American ground forces had suffered more than 6,000 casualties, including 901 taken prisoner. The North Koreans simply executed many of their American captives.

As bad as the situation at Pusan was, the Americans did have complete control of the air. Within days of American entry into the war, Navy, Air Force, and Marine aircraft swept the North Korean air force from the skies. With unchallenged mastery of the skies, American planes repeatedly strafed and bombed North Korean supply columns and troop concentrations. Before long, the planes were doing so much damage that the enemy could only move at night. Soon supply problems were slowing down North Korean attacks. In the final analysis, this air support helped save the Pusan Perimeter from total annihilation.

As bad as the situation at Pusan was, the Americans did have complete control of the air. Within days of American entry into the war, Navy, Air Force, and Marine aircraft swept the North Korean air force from the skies. With unchallenged mastery of the skies, American planes repeatedly strafed and bombed North Korean supply columns and troop concentrations. Before long, the planes were doing so much damage that the enemy could only move at night. Soon supply problems were slowing down North Korean attacks. In the final analysis, this air support helped save the Pusan Perimeter from total annihilation.

Calling on MacArthur

Seventy-year-old Gen. Douglas MacArthur was the supreme UN commander. During World War II, MacArthur had earned a hero’s reputation for his exploits in the Pacific Theater (for details, see Chapter 16). Since then, he had presided over the American occupation of Japan.

By early September, he knew that North Korean attacks on the Pusan Perimeter were losing momentum and that his forces there were getting stronger by the day, thanks to reinforcements. He now had 500 tanks and 180,000 troops in the perimeter, plus complete control of the air and sea. To MacArthur, the time had come to unleash a bold counterattack and turn the tide of the war.

Invading at Inchon

Instead of attacking from within the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur proposed an amphibious invasion at Inchon, South Korea, near Seoul, far behind the North Korean lines. The idea was to unhinge the whole North Korean army, outflank them, force them back from the Pusan Perimeter, and then cut them off before they could retreat from South Korea. The plan was so risky that many of the military service chiefs in Washington, D.C., initially opposed it.

Instead of attacking from within the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur proposed an amphibious invasion at Inchon, South Korea, near Seoul, far behind the North Korean lines. The idea was to unhinge the whole North Korean army, outflank them, force them back from the Pusan Perimeter, and then cut them off before they could retreat from South Korea. The plan was so risky that many of the military service chiefs in Washington, D.C., initially opposed it.

The main problem was Inchon itself. The tides and winds were tricky and unpredictable. The area didn’t have beaches so much as wide-open tidal flats that forced invaders to reveal themselves. Only MacArthur’s reputation swayed Truman and the generals in Washington to approve his invasion plan.

On September 15, 1950, the 1st Marine Division led the way into Inchon against almost no opposition. The invasion succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. Within two weeks, the North Koreans were in full retreat, UN forces had liberated Seoul, and the troops were in a position to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea. The military situation had completely reversed. Now the North Koreans were on the verge of losing the war.

Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese Communist leader, actually warned the North Koreans in late August 1950 that the Americans might make an amphibious invasion at Inchon. From the start, Mao had been planning to enter this war, so he was massing troops along his common border with North Korea, and he was studying the situation in South Korea intently. His intelligence reports, combined with what he knew of American amphibious capability, made him believe an invasion was coming. Alas, the North Koreans didn’t heed his warning.

Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese Communist leader, actually warned the North Koreans in late August 1950 that the Americans might make an amphibious invasion at Inchon. From the start, Mao had been planning to enter this war, so he was massing troops along his common border with North Korea, and he was studying the situation in South Korea intently. His intelligence reports, combined with what he knew of American amphibious capability, made him believe an invasion was coming. Alas, the North Koreans didn’t heed his warning.

Crossing the line: The 38th parallel

Crossing the 38th parallel into North Korea was a political, not a military decision. The UN mandate had only called for the return to the status quo in Korea. Moreover, the status quo was in line with Truman’s policy to contain, but not necessarily roll back, Communism. Invading North Korea would mean embracing a more ambitious policy of rolling back Communism, not just containing it. Taking this into consideration, Truman decided, for several reasons, to send his troops into Korea:

He had a good chance of eliminating the Communist regime in North Korea and uniting the whole country under Rhee’s anti-Communist government.

He was concerned that if he stopped at the parallel, the North Koreans would regroup and invade the South again.

Many of his UN partners favored invading North Korea.

In a moral sense, Truman liked the idea of liberating the North Korean people from Communism.

With UN approval, Truman gave the go-ahead to invade North Korea. American troops crossed the parallel on October 7, 1950. In the next few weeks, they took the North Korean capital of Pyongyang and overran much of the country.

Thinking wrong about China

In crossing the parallel, the main concern now for UN forces was the possibility of Chinese entry into the war. China was just across the Yalu River border from North Korea. The Communist Chinese might not like the idea of an American-dominated army marching all the way to their border. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) advised Truman that the Chinese, after their long civil war, were in no position to intervene in Korea. MacArthur told the president the same thing during a brief meeting at Wake Island on October 15, 1950. They could not have been more wrong.

Thanks to recently released Chinese government documents, we now know that the Chinese intended to enter this war from the beginning, even before U.S. involvement. After American entry into the war, and with the great reversal of fortune that occurred in the UN’s favor in the fall of 1950, the Chinese were even more determined to get into the war. For months they had been massing troops on the North Korean border.

Thanks to recently released Chinese government documents, we now know that the Chinese intended to enter this war from the beginning, even before U.S. involvement. After American entry into the war, and with the great reversal of fortune that occurred in the UN’s favor in the fall of 1950, the Chinese were even more determined to get into the war. For months they had been massing troops on the North Korean border.

In late October, Mao ordered a quarter million of those soldiers to cross the Yalu into Korea. Immediately, they clashed with American and South Korean soldiers. When MacArthur’s commanders on the ground told him that they were now facing Chinese soldiers, the general refused to believe it. Aloof from the situation on the front lines and surrounded by a skeptical staff of mediocre sycophants in his Tokyo headquarters, he couldn’t bring himself to face the truth of Chinese involvement.

Changing the face of the war

Like phantoms in the night, the Chinese, by early November, melted away almost as quickly as they had arrived. Feeling vindicated, MacArthur breathed a sigh of relief and initiated his final push to the Yalu River. However, the Chinese had simply retreated to lick their wounds. Mao was amassing an even larger force of more than half a million soldiers. MacArthur had about 250,000, many of whom were advancing piecemeal, separated from one another, in the mountain gaps so prevalent in North Korea. In late November, the Chinese attacked them in force, forcing a major retreat, changing the whole nature of the war.

In the East, the 1st Marine Division, the U.S. Army’s 3rd and 7th Divisions, plus South Korean troops bitterly fought their way back to evacuation ports in Hungnam and Wonsan. The U.S. Navy evacuated to South Korea 105,000 American and South Korean troops, along with about 100,000 North Korean civilians who wanted to escape Communism. This desperate struggle is generally known as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. In the West, UN forces retreated overland, back across the parallel, with the Chinese threatening to annihilate them every step of the way.

The fighting around Chosin Reservoir was some of the worst that American soldiers have ever experienced. Temperatures were below zero. The wind was howling. Snow and ice covered the cold hills that permeated the area. The Chinese attacked, usually at night, in human waves, sometimes outnumbering the Americans ten-to-one. Soldiers or Marines manned perimeters, usually designed to keep control of key road nets or bridges. When the Chinese attacked them, they would blow bugles and then charge. The average Chinese soldier fought with suicidal fanaticism. The Americans would mow row after row of enemy soldiers down, and still they would keep coming. Their screams as they charged were bloodcurdling. Only firepower and the courageous resolve of American combat soldiers kept Chosin from ending in complete disaster.

The fighting around Chosin Reservoir was some of the worst that American soldiers have ever experienced. Temperatures were below zero. The wind was howling. Snow and ice covered the cold hills that permeated the area. The Chinese attacked, usually at night, in human waves, sometimes outnumbering the Americans ten-to-one. Soldiers or Marines manned perimeters, usually designed to keep control of key road nets or bridges. When the Chinese attacked them, they would blow bugles and then charge. The average Chinese soldier fought with suicidal fanaticism. The Americans would mow row after row of enemy soldiers down, and still they would keep coming. Their screams as they charged were bloodcurdling. Only firepower and the courageous resolve of American combat soldiers kept Chosin from ending in complete disaster.

Gaining and losing ground

“We face an entirely new war,” MacArthur now admitted to the president. The general was absolutely right. With China in the war (and plenty of covert Soviet support), the Communists had great momentum. While UN forces were in headlong retreat, the Communists recaptured Seoul. But eventually, supply problems and horrendous casualties forced the enemy to halt. In February and March, the UN counterattacked and liberated Seoul for good. For much of the rest of 1951, the front lines ebbed and flowed as both sides launched limited offensives. The fighting was fierce, but neither side could gain a decisive advantage.

Truman didn’t want this war to turn into World War III. After the failed rollback experience in North Korea, he sought to limit the war to the smaller objectives of preserving the status quo and implementing NSC-68. Even so, in January 1951, he and Congress approved the following emergency wartime measures:

Reintroduced selective service (the draft)

Put together a $50 billion defense budget

Increased the size of the Army, including the deployment of tens of thousands more troops to Europe to deter the Soviets

Doubled the size of the Air Force

Replacing a rebellious MacArthur

In the spring of 1951, the war turned in the UN’s favor and, once again, American troops were in a position to cross the 38th parallel. Not wanting to invade North Korea again, Truman intended to halt at the parallel, negotiate a cease-fire (a mutual agreement to stop fighting) with the Communists, and end the war on the original UN mandate of preserving the status quo.

MacArthur vehemently disagreed. He wanted to push across the parallel, overrun North Korea, and even continue into China if necessary. In essence, Truman was sticking with containment while MacArthur favored rollback. Instead of keeping his opinions to himself, MacArthur went public with them, undercutting Truman’s plans and ending any hope of a quick end to the war. MacArthur then wrote a public letter to a Republican congressman declaring that there was “no substitute for victory.”

MacArthur and Truman never liked each other. They were very different individuals with radically divergent backgrounds. MacArthur was the son of a general and a West Pointer who had spent all of his adult life in the Army. He was aristocratic, egotistical, and politically ambitious. The son of a Missouri small farmer, Truman’s origins were humble. His family was too poor to send him to college. In World War I, he had served in combat as an artillery officer (for more, see Chapter 14). Truman spent much of his life barely scraping by before going into politics. He disliked arrogant people, and he had a near-reverence for the common man. So, to him, MacArthur was nothing more than an overblown “brass hat.” To MacArthur, Truman was a little man who was out of his depth as president.

MacArthur and Truman never liked each other. They were very different individuals with radically divergent backgrounds. MacArthur was the son of a general and a West Pointer who had spent all of his adult life in the Army. He was aristocratic, egotistical, and politically ambitious. The son of a Missouri small farmer, Truman’s origins were humble. His family was too poor to send him to college. In World War I, he had served in combat as an artillery officer (for more, see Chapter 14). Truman spent much of his life barely scraping by before going into politics. He disliked arrogant people, and he had a near-reverence for the common man. So, to him, MacArthur was nothing more than an overblown “brass hat.” To MacArthur, Truman was a little man who was out of his depth as president.

Truman was furious with MacArthur for deliberately disobeying his commander-in-chief. The president felt that MacArthur’s actions threatened the traditional American principle of civilian control over the military. Even though MacArthur was popular with the American people, Truman relieved him on April 11, 1951, ending his 50-year career.

MacArthur returned home to a tumultuous reception. He even addressed a joint session of Congress and rode in ticker tape parades in his honor. Over time, the excitement waned, and the American people grew less enamored of the old general. He hoped to launch a bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1952, but his candidacy went nowhere. Truman later summed up the disagreement between the two men quite succinctly. “General MacArthur was ready to risk general war. I was not.” Gen. Matthew Ridgway succeeded MacArthur as commander of UN forces in Korea.

Stalemate and Armistice

From the fall of 1951 until the end of the war in July 1953, the front lines stalemated while on-and-off peace negotiations proceeded. Each side now understood that total victory was no longer possible without a larger war that no one really wanted. Both hoped to end the war advantageously but not at great cost. So they were content to construct extensive front-line defenses along the ubiquitous Korean hills on either side of the parallel and engage in stationary warfare.

In the meantime, the Communist North Koreans and Chinese engaged in a dizzying series of negotiations with UN military leaders. The main sticking point in the negotiations was the exchange of prisoners of war (POWs). Because many North Korean and Chinese POWs didn’t want to return to their Communist homes, the UN didn’t want to force them. Enraged, the Communist negotiators threatened not to return UN POWs until all of their men were returned. It took nearly two tortuous years of peace talks for negotiators to finally hammer out a POW exchange agreement and sign an armistice to end the war.

Enduring on the main line of resistance

For the last two years of the war, the average American combat soldier served in static positions along the main line of resistance, or MLR. The MLR consisted of a long series of mutually supporting bunkers, trenches, observation posts, minefields, and listening posts that snaked along Korea’s considerable hills, all the way across the peninsula.

Soldiers generally spent two months on the MLR for every month off the line. Most of the men were draftees serving a tour of duty that often lasted for one year. They were exposed to the freezing cold of the Korean winter and the heat of the country’s summer. They ate prepackaged rations or hastily cooked food. They spent their days on watch for enemy attacks, patrolled at night, and often endured intense artillery and mortar bombardments. Periodically, one side or the other would make a limited attack that was usually designed to garner some advantage at the negotiating table. Some of these battles were among the fiercest of the war.

Soldiers generally spent two months on the MLR for every month off the line. Most of the men were draftees serving a tour of duty that often lasted for one year. They were exposed to the freezing cold of the Korean winter and the heat of the country’s summer. They ate prepackaged rations or hastily cooked food. They spent their days on watch for enemy attacks, patrolled at night, and often endured intense artillery and mortar bombardments. Periodically, one side or the other would make a limited attack that was usually designed to garner some advantage at the negotiating table. Some of these battles were among the fiercest of the war.

Ending the war: Eisenhower finishes what Truman began

As the war dragged on into the fall of 1952, Harry Truman decided to retire rather than run for reelection. He was succeeded by Dwight Eisenhower (“Ike”), a World War II hero and Republican who promised to go to Korea and break the stalemate. The American people elected Ike, in part, because they had great confidence in his ability to deal with the war in Korea.

True to his promise, Eisenhower visited Korea in late November 1952, sized up the situation, came home, and concocted a plan of action. He shared Truman’s war objectives and had no wish to flirt with World War III. However, he thought the best way to end the war was to threaten to widen it. In the ongoing peace negotiations, he conveyed this threat to the Communists and even hinted darkly that he was considering using nuclear weapons.

Eisenhower’s tough rhetoric produced the desired effect. In the spring and summer of 1953, the peace negotiations gathered momentum. The Communists were concerned about Ike’s hawkish intentions, but they also wanted peace for two other reasons:

Eisenhower’s tough rhetoric produced the desired effect. In the spring and summer of 1953, the peace negotiations gathered momentum. The Communists were concerned about Ike’s hawkish intentions, but they also wanted peace for two other reasons:

Josef Stalin had died in March 1953, throwing the Soviet hierarchy into disarray. The turmoil diminished Russian interest in Korea, weakening the Communist position there.

Chinese leaders now saw Korea as a dead end, and because they were involved in a burgeoning war in Vietnam (for more, see Chapter 19), they wanted to make peace in Korea.

On July 27, 1953, the two sides signed an armistice, creating a cease-fire, with the two Koreas intact. They created a tense demilitarized zone (or DMZ), a heavily fortified no man’s land at the 38th parallel that both sides were to patrol in the years to come.

Technically, the two Koreas are still at war, and over the years, plenty of fighting has taken place along the DMZ, with some loss of life. The worst bloodshed, of course, took place between 1950 and 1953, when 5 million people, most of whom were Korean, died in the three terrible years of conventional war.

Lasting Legacies and Entrenched Contrasts

For the United States, the Korean War was a limited, albeit difficult, victory. The Americans succeeded in saving South Korea from Communism. South Korea even gained some North Korean territory in the final armistice agreement. In the years after the war, the United States extended and strengthened alliances with non-Communist states in both Europe and Asia. The war left several other legacies:

Total victory was not always desirable or attainable in the nuclear age because it could stem from nuclear war.

American power was not unlimited.

Containment would be costly, and it would sometimes be bloody.

From now on, America would maintain a large and costly but powerful military to contain Communism.

The United States would keep a permanent military presence in South Korea that continues to this day.

The war led to many significant legacies for the two Koreas. North Korea became one of the Soviet Union’s closest allies and hardened into a repressive, heavily militarized state in which Kim Il-Sung, and later his son Kim Jong-Il, wielded absolute power. After a period of industrial growth, North Korea’s economy collapsed in the 1980s. The result was famine and more repression. Since the 1990s, North Korea’s attempts to build a nuclear weapon have led to major tension with South Korea and the United States.

South Korea grew into a staunch American ally after the war. The country was not a true democracy until the late 1980s, when the authoritarian, military government gave way to free elections and political parties. By that time, South Korea had grown into a powerful capitalist economy and a significant military power. Today, South Korea is a rebellious but reasonably stable democracy. Many Koreans, North and South, hope their nation will one day be reunited peacefully.