Chapter 21

The Long War Ahead: Terrorism, Afghanistan, and Iraq

In This Chapter

Absorbing a devastating attack at home

Invading Afghanistan

Taking down Saddam Hussein

Struggling for stability in Iraq

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States (9/11 as the attacks are generally known) ushered in a new and deadlier phase to a long-festering and escalating struggle against terrorism. Led by President George W. Bush, the United States government launched a “Global War on Terror” against Islamic radicalism. The first manifestation of the war on terrorism came in October 2001 with the invasion of Afghanistan, home to Al Qaeda and the Taliban, two extremist organizations that were responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Subsequently, in 2003, Bush widened the global struggle, invading Iraq to remove his father’s old adversary, Saddam Hussein, from power.

In this chapter, I trace the long conflict between Muslim terrorists and the United States. I take a look at the invasion of Afghanistan and how an American-led coalition removed the Taliban from power, but then found itself involved in a long-term occupation of the country to build a new democracy in hopes of preventing the Taliban from taking over again. In the second half of the chapter, I explore why the United States invaded Iraq and outline how a lightning military campaign toppled Saddam. Finally, I explain how Saddam’s removal led to a long, controversial, and bloody American occupation of Iraq.

A New War against an Old Enemy

In the early 19th century, the United States fought North African Barbary pirates for access to Mediterranean Sea routes (for more, see Chapter 8). These pirates just happened to be Muslims. The conflict was really fueled more by economics than religious ideals. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, American soldiers fought against the Moros, a group of Muslim Filipinos who, for religious and nationalistic reasons, opposed the U.S. occupation of the Philippines (for more, see Chapter 13).

But the trouble between America and Islamic fundamentalists really began after World War II, when the American presence in the Middle East — home to millions of devout Muslims — increased because of the growing American dependence on the region’s oil. Many Muslims didn’t like how the American culture, language, and economic influence were creeping into their respective homelands. Moreover, the United States generally supported the Jewish nation-state of Israel, a country that most Middle Eastern Arab Muslims hated because of their own latent anti-Semitism and their belief that the Jews, with American support, created Israel by stealing land from Palestinian Arabs. In the early 1970s, this seething conflict boiled over, as Islamic radicals began to employ terrorism against the Israelis, the Americans, and anyone else they perceived as an opponent of their fundamentalist views.

Terrorism is a tactic of indiscriminate violence used for some sort of political, religious, or ideological goal. Terrorists believe that there is no such thing as a noncombatant. Any member of an enemy group is fair game, from highly trained soldiers to infants and the elderly. Terrorists generally operate within small, cohesive, shadowy groups of true believers. Terrorist networks are multinational. They can, and do, exist in nearly every country in the world. Terrorists specialize in hit-and-run, wanton violence and the threat of the same. Examples of terrorist tactics include the bombing of crowded places such as restaurants, airports, sporting events, and bars; hijacking aircraft; taking hostages; stealing weapons; assassinating prominent political leaders; and blowing up buildings. Some terrorists, particularly Islamic radicals, engage in suicide attacks. Terrorists rely on vast networks of surreptitious financial and political support from like-minded, but more “respectable,” cohorts. Ultimately, the greatest terrorist weapon is fear and intimidation. Osama bin Laden, who masterminded the 9/11 attacks, is the most famous example of a terrorist.

Terrorism is a tactic of indiscriminate violence used for some sort of political, religious, or ideological goal. Terrorists believe that there is no such thing as a noncombatant. Any member of an enemy group is fair game, from highly trained soldiers to infants and the elderly. Terrorists generally operate within small, cohesive, shadowy groups of true believers. Terrorist networks are multinational. They can, and do, exist in nearly every country in the world. Terrorists specialize in hit-and-run, wanton violence and the threat of the same. Examples of terrorist tactics include the bombing of crowded places such as restaurants, airports, sporting events, and bars; hijacking aircraft; taking hostages; stealing weapons; assassinating prominent political leaders; and blowing up buildings. Some terrorists, particularly Islamic radicals, engage in suicide attacks. Terrorists rely on vast networks of surreptitious financial and political support from like-minded, but more “respectable,” cohorts. Ultimately, the greatest terrorist weapon is fear and intimidation. Osama bin Laden, who masterminded the 9/11 attacks, is the most famous example of a terrorist.

Sleeping through terrorism’s rise

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, instances of Islamic fundamentalist terrorism grew, with a litany of attacks against Israel and the United States:

At the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany, Palestinian terrorists abducted and killed 11 Israeli athletes.

In 1977, Muslim terrorists took control of several buildings in Washington, D.C., and held 123 hostages. They killed a reporter and wounded several other people before surrendering to authorities.

On November 4, 1979, a mob of Iranian fundamentalists overran the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage, holding them for more than a year. This crisis prompted a failed rescued mission in April 1980 by United States military forces. It also was one of the reasons why President Jimmy Carter failed to win reelection in the fall of 1980.

On April 18, 1983, Islamic terrorists packed 1,000 pounds of explosives into a pickup truck and bombed the U.S. embassy in Lebanon, killing 63 people, including 17 Americans.

On October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber rammed a truck with 1,500 pounds of explosives into the Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, killing 241 Marines and wounding 100 others.

On December 21, 1988, Libyan terrorists blew up a Pan American passenger plane over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 281 people.

Preoccupied with the Cold War (see Chapter 17 for more), American leaders did little to combat Islamic terrorism in the 1970s and 1980s.

Pushing the snooze button — more Islamic terrorism in the 1990s

In 1992, the Cold War had ended, an American-led coalition had defeated Saddam Hussein in the Gulf War (for more, see Chapter 20), and most Americans turned their attention to domestic issues. Thinking that the United States had defeated all of its significant enemies, people spoke of a peace dividend. Politicians mirrored this “all is well” mentality. President Bill Clinton and Congress teamed up to cut the defense budget and the size of the armed forces.

Unfortunately, Islamic radicals continued to make war on the United States with a series of bloody attacks:

On February 26, 1993, Al Qaeda–linked terrorists detonated a powerful car bomb in the parking garage of the World Trade Center in New York City. The blast killed 6 people and injured 1,042 others, but it didn’t collapse the Trade Center towers as the terrorists had hoped.

Later that same year, Saddam Hussein tried to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush while Bush was visiting Kuwait.

On June 26, 1996, Al Qaeda terrorists detonated a car bomb at the Khobar Towers, a U.S. military housing complex in Saudi Arabia. The blast killed 19 Americans and wounded 372 people.

On August 7, 1998, Al Qaeda operatives bombed U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 12 Americans, plus numerous local embassy employees in both countries.

Al Qaeda struck again on October 12, 2000, in the Yemeni port of Aden. That morning two suicide bombers sailed a small, explosive-laden craft into the USS Cole, touching off an explosion that killed 17 American sailors.

The American response to these attacks was tepid. Shocking as these events were, none of them touched off any kind of political consensus among the American people to retaliate against Al Qaeda in any meaningful way. It took the bloody tragedy of 9/11 to finally change that political climate.

Jarring awake to an ominous reality

The sight was strange, almost surreal. On September 11, 2001, as millions watched on television or on the ground, an airliner slammed into one of the World Trade Center towers in New York City. Was this some sort of dreadful navigation error? Perhaps the pilots had died? Weather couldn’t be a factor because the day was clear and bright. Then, in the next instant, a second airliner hit the Trade Center’s other tower. Soon thereafter, a third plane crashed into the Pentagon, near Washington, D.C. Yet another airliner mysteriously crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

As the Trade Center towers collapsed and the Pentagon smoldered, the awful reality of what had happened began to sink in. The United States had been attacked by a group of dedicated, cunning, and suicidal terrorists headed by Osama bin Laden. These 19 terrorists were Islamic fundamentalist radicals who hated the United States and everything it stood for. On September 11, they butchered 2,973 people. This heinous attack was just the latest event in a 30-year struggle between the United States and Islamic extremists around the world. But it finally made Americans aware that the nation was not immune from people who would go to any extreme to express their venom toward the United States.

Osama bin Laden was born into a wealthy family in Saudi Arabia. A devout Muslim, he fought against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan during the 1980s (for more on that war, see Chapter 17). Bin Laden didn’t approve of the American presence in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War (that war is covered in Chapter 20). To him, the presence of American infidels (nonbelievers) on sacred Islamic soil was an abomination that must be avenged. Thus began his long “holy war” against the United States. After 9/11, the United States government offered a $25 million reward for bin Laden.

Osama bin Laden was born into a wealthy family in Saudi Arabia. A devout Muslim, he fought against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan during the 1980s (for more on that war, see Chapter 17). Bin Laden didn’t approve of the American presence in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War (that war is covered in Chapter 20). To him, the presence of American infidels (nonbelievers) on sacred Islamic soil was an abomination that must be avenged. Thus began his long “holy war” against the United States. After 9/11, the United States government offered a $25 million reward for bin Laden.

Invading Afghanistan

Within days of 9/11, American intelligence analysts and policymakers knew that bin Laden’s Al Qaeda and its close ally, the Taliban, were responsible for the attacks. The Taliban was a hard-line group of Muslim fundamentalists who had come to power in Afghanistan several years after the Soviet withdrawal from that country in 1989. With Taliban approval, Al Qaeda was using Afghanistan as a base from which to launch terrorist operations. As dedicated, violent Muslim fundamentalists, the two groups were basically ideological bedfellows and made common cause with each other. Knowing this, President George W. Bush, after 9/11, demanded that the Taliban turn over custody of bin Laden and anyone else responsible for the killings. The Taliban government refused to comply with these demands. So, in October 2001, the United States and its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) invaded Afghanistan with the goals of toppling the Taliban, destroying Al Qaeda, and apprehending bin Laden.

Taking down the Taliban

Afghanistan is a highly factionalized country with myriad warring tribes and interest groups. The country’s harsh climate and rugged mountains make mere existence a struggle for many Afghans. American and NATO planners knew that it made no sense to invade the country with large conventional military forces or great numbers of soldiers. Instead, the U.S. and its partners infiltrated the country with small, highly trained Special Forces teams that made common cause with the Taliban’s many enemies to create a powerful fighting bloc known as the Northern Alliance. Special Forces soldiers helped train, equip, and arm the Afghan members of the Northern Alliance.

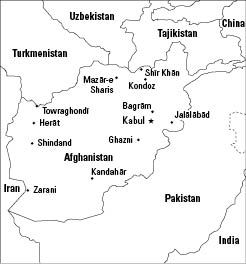

In combat, the Americans made liberal use of airpower to support Northern Alliance attacks and batter Taliban positions. In a lightning two-month campaign, the Northern Alliance and the Americans drove the Taliban from power. Taliban and Al Qaeda survivors generally did not surrender, though. Instead they retreated east, across the rough, mountainous border areas, into western Pakistan (see Figure 21-1), a fertile place for them because of the large number of Muslim fundamentalists in that country. There the survivors licked their wounds, evaded Pakistani government troops, and prepared to fight the American-led coalition in Afghanistan another day. For fear of provoking a revolution by Muslim radicals, the military junta that controlled the Pakistani government did little to apprehend the Taliban and Al Qaeda. In the meantime, Gen. Tommy Franks, the American commander, reinforced his Special Forces teams with regular troops specially trained for mountain warfare, such as the 10th Mountain Division.

Figure 21-1: Map of Afghanistan.

The Taliban regime was highly repressive. As hard-line Islamic radicals, they believed in no separation of church and state. In their case, the Muslim faith was the state, and they were the keepers of that faith. Everyone was to comply with shariah, or Muslim, laws. Needless to say, infidels such as Christians, Jews, Buddhists, or atheists were highly unwelcome. The Taliban’s greatest repression was against women. They forced women to wear heavy, robe-like burqas that covered their entire bodies. Women were allowed no education after the age of 8 years old. Before that, their only schooling would be in the Koran, the holy book of Islam. Women couldn’t work, travel alone, drive, sing, dance, or even be photographed. Adultery was punishable by death. Religious police hunted down violators and imposed severe punishments, which ranged from public floggings to facial disfigurement and even outright executions.

The Taliban regime was highly repressive. As hard-line Islamic radicals, they believed in no separation of church and state. In their case, the Muslim faith was the state, and they were the keepers of that faith. Everyone was to comply with shariah, or Muslim, laws. Needless to say, infidels such as Christians, Jews, Buddhists, or atheists were highly unwelcome. The Taliban’s greatest repression was against women. They forced women to wear heavy, robe-like burqas that covered their entire bodies. Women were allowed no education after the age of 8 years old. Before that, their only schooling would be in the Koran, the holy book of Islam. Women couldn’t work, travel alone, drive, sing, dance, or even be photographed. Adultery was punishable by death. Religious police hunted down violators and imposed severe punishments, which ranged from public floggings to facial disfigurement and even outright executions.

Striking with Operation Anaconda

Even though the initial military campaign in Afghanistan had been a big success for the U.S. and its allies, thousands of enemy fighters, including bin Laden, were still at large. In an effort to cut them off and round them up, the Allies, in March 2002, launched Operation Anaconda in Paktia province. The attacking forces, numbering about 2,000 soldiers, consisted of a multinational blend of regular and irregular troops:

Elements of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division and the 101st Air Assault Division

Army Rangers, Special Forces teams, Navy SEAL (Sea, Air, and Land) teams, and British Royal Marines

Afghan fighters

Soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry

Special Forces teams from Germany, New Zealand, and Australia

Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters were extensively dug into caves, ridges, and mountainsides. They laid down withering fire on Allied soldiers who assaulted from helicopters and from the valleys.

Perhaps the most intense fighting of this operation took place at Taku Ghar on March 3–4, 2002, when two SEAL teams engaged in a vicious close-quarters firefight with several hundred Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters. The enemy fighters then shot down a helicopter carrying a Ranger quick-reaction force that was coming to the aid of the SEALs. Thus ensued a 24-hour battle in which the Americans fought the enemy troops to a standstill with the help of deadly airstrikes. Rescue forces eventually extracted the Americans who had killed 200 enemy fighters, at the cost of 7 of their own dead comrades.

Operation Anaconda cost the enemy between 500 and 800 dead, but it was not decisive. Osama bin Laden got away, probably into Pakistan, and remained a thorn in the American side. From here on out, the Taliban and Al Qaeda rested, replenished, and trained new fighters along the lawless border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Using these areas as bases, they forayed into Afghanistan to fight coalition forces.

A new Afghanistan government and a counterinsurgency struggle

After ejecting the Taliban from power, the U.S., in conjunction with its NATO partners and the United Nations (UN), installed a new democratic government in Afghanistan. Afghans voted in elections for the first time in decades, electing Hamid Karzai, a close U.S. ally, as their president. With extensive American aid, the new government created its own military, known as the Afghan National Army (ANA). American and NATO soldiers worked closely with ANA troops, training them, arming them, equipping them, and teaching them how to defeat the Taliban. Afghanistan became a moderately stable country, but with some serious economic and security problems that required a continued NATO presence.

From the summer of 2002 onward, Afghanistan became a counterinsurgency struggle. Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters conducted guerrilla warfare against the ANA and NATO throughout Afghanistan. The main enemy tactics were improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on roads, ambushes in mountain passes, and periodic efforts to take over villages in the country’s many remote areas. To contain the insurgency, the U.S. and its allies maintained about 10,000 soldiers in Afghanistan. Their counterinsurgency struggle continued into 2007 and beyond.

From the summer of 2002 onward, Afghanistan became a counterinsurgency struggle. Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters conducted guerrilla warfare against the ANA and NATO throughout Afghanistan. The main enemy tactics were improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on roads, ambushes in mountain passes, and periodic efforts to take over villages in the country’s many remote areas. To contain the insurgency, the U.S. and its allies maintained about 10,000 soldiers in Afghanistan. Their counterinsurgency struggle continued into 2007 and beyond.

Although the counterinsurgent war in Afghanistan was basically successful, two serious, long-term problems vexed the Americans:

Western Pakistan was a sanctuary for the Taliban and Al Qaeda. These terrorist organizations recruited young Muslims in Pakistan, indoctrinated them at schools known as madrasahs, and sent them into Afghanistan to make trouble. Osama bin Laden himself probably took refuge in Pakistan.

Opium was the main cash crop of Afghanistan. For the Americans, cutting off the opium trade risked destroying the fledgling Afghan economy. However, keeping it in place would support the world drug trade.

Resuming the fight with Saddam: The Iraq War

On January 29, 2002, President George W. Bush, during his State of the Union Address, described several terrorist-sponsoring nations as the “axis of evil.” One of those nations was Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. In 1991, Saddam had taken over neighboring Kuwait (for more, see Chapter 20). In response, the United States and a vast coalition fought a successful war to force Saddam out of Kuwait. However, he kept control of power in Iraq, partly through the ruthless suppression of war-inspired uprisings in his country. He had agreed, though, to verifiably destroy any nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in his possession.

Instead, throughout the 1990s, Saddam flouted UN mandates, shot at U.S. and British planes that tried to enforce a no-fly zone over parts of Iraq, and concealed information about Iraq’s WMD program. These weapons were a major concern to American leaders partially because of Saddam’s aggressive and tyrannical nature, but also because he had actually used chemical weapons to kill rebellious Iraqis in 1988.

By 2002, Bush, and many intelligence analysts from a variety of nations believed that, contrary to UN mandates, Saddam secretly possessed weapons of mass destruction. Saddam’s less-than-forthright dealings with UN weapons inspectors during their visits to Iraq in 1998 and 2002 only added to these suspicions. Bush and other world leaders, like British Prime Minister Tony Blair, also thought that Saddam had strong ties with terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda. The president worried that Saddam would sell nuclear or chemical weapons to terrorists, who could then use the weapons to kill millions of Americans. Feeling, in the wake of 9/11, that he had to prevent such a situation from ever developing, Bush came to believe that the United States must invade Iraq to remove Saddam from power unless he honestly proved he had no WMDs.

The controversial decision for war

Saddam never proved whether or not he had weapons of mass destruction. So, in the fall of 2002 and the early months of 2003, the Bush administration prepared for war with Iraq. Bush had little trouble lining up the necessary war mandate from Congress. But he had a much more difficult time gaining UN approval for his prospective invasion of Iraq.

Led by France and Russia, the UN Security Council opposed an American-sponsored resolution for war. A detailed pro-war presentation by Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had earned universal acclaim for his service as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the Gulf War, did little to persuade the UN. In the end, enough Security Council members opposed military action that the UN would not approve of Bush’s war resolution. In defiance of the UN, the president decided to go to war anyway.

Over time, the decision process for the invasion of Iraq grew into one of the most controversial in U.S. military history because

UN leaders viewed the war in Iraq as illegal.

After overrunning Iraq, U.S. forces never found any WMDs, undermining one of the administration’s major justifications for war.

Saddam’s ties with Al Qaeda and other terrorist organizations weren’t as extensive as Bush had argued.

Bush called his national security policy preemption. He argued that, after 9/11, the United States could no longer afford to simply react to security threats. Rather, it must now preempt such threats — in places like Iraq — before they cost American lives. Prior to the Iraq War, most Americans agreed with preemption. However, when the war grew into a long and difficult struggle with thousands of American casualties, support for preemption diminished dramatically. Opponents of the policy argued that it probably cost more American lives in military campaigns than it saved at home. Plus, they argued, it stimulated as much bloodshed and terror around the world as it prevented.

Bush called his national security policy preemption. He argued that, after 9/11, the United States could no longer afford to simply react to security threats. Rather, it must now preempt such threats — in places like Iraq — before they cost American lives. Prior to the Iraq War, most Americans agreed with preemption. However, when the war grew into a long and difficult struggle with thousands of American casualties, support for preemption diminished dramatically. Opponents of the policy argued that it probably cost more American lives in military campaigns than it saved at home. Plus, they argued, it stimulated as much bloodshed and terror around the world as it prevented.

Even without UN approval, Bush still put together an anti-Saddam alliance, but it was nowhere near as vast as the coalition his father had built in 1990 to repel Saddam from Kuwait. In 2003, the Americans built an alliance that George W. Bush called “the coalition of the willing.” This coalition included more than 40 countries, most of which simply supported the invasion politically or provided some sort of aid. Only a few sent troops. Ninety-eight percent of the invading troops in 2003 were either British or American. Only Poland, Australia, and Denmark contributed troops to the invasion force. Several other countries, including Spain, Italy, Ukraine, and Japan, sent troops for the occupation that followed the invasion. However, by 2006, nearly all of these countries had withdrawn their soldiers from Iraq.

Even without UN approval, Bush still put together an anti-Saddam alliance, but it was nowhere near as vast as the coalition his father had built in 1990 to repel Saddam from Kuwait. In 2003, the Americans built an alliance that George W. Bush called “the coalition of the willing.” This coalition included more than 40 countries, most of which simply supported the invasion politically or provided some sort of aid. Only a few sent troops. Ninety-eight percent of the invading troops in 2003 were either British or American. Only Poland, Australia, and Denmark contributed troops to the invasion force. Several other countries, including Spain, Italy, Ukraine, and Japan, sent troops for the occupation that followed the invasion. However, by 2006, nearly all of these countries had withdrawn their soldiers from Iraq.

“On to Baghdad!” The invasion of Iraq

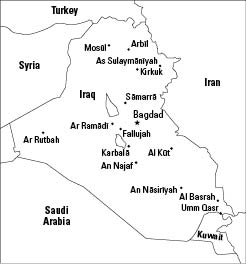

In late 2002 and early 2003, U.S. and British forces massed along the Kuwait-Iraq border (see Figure 21-2). By March, about 248,000 American troops and 45,000 British soldiers were in place. Iraq had about 390,000 regular soldiers, 45,000 Fedayeen Saddam paramilitary fighters, and roughly 120,000 Republican Guard troops, who were among Saddam’s best, most loyal men. On March 17, 2003, Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam. He and his sons were to leave Iraq within two days or face invasion. The ultimatum passed with no response. So, on March 20, Bush gave the order to invade.

Figure 21-2: Map of Iraq.

Gen. Tommy Franks, the coalition commander, devised a bold invasion plan that depended upon speed, firepower, technology, and the lethality of American weapons. His objective was to reach Baghdad and destroy Saddam’s regime as quickly as possible. He made liberal use of devastating American airstrikes — what reporters called “shock and awe.” On the ground, he intended to seize and control all northerly roads that led to the capital, dash north, bypass other major cities, and avoid costly urban combat. He only had enough ground forces for a two-pronged advance. In the east, the British 1st Armored Division’s mission was to seize Basrah, the second-largest city in Iraq. He ordered the 1st Marine Division, plus other supporting Marine units, to advance north, with the intention of entering Baghdad from the east. To the west of the Marines, the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division was to advance along the western side of the Euphrates River, cross that river, and enter Baghdad from the west. Follow-up units from the 101st Air Assault Division and the 82nd Airborne Division drew the mission of mopping up any resistance that the heavily mechanized 3rd Division bypassed. Gen. Franks planned to stage another major unit, the 4th Infantry Division, in Turkey and order them to invade Iraq from the north. But the Turkish government wouldn’t agree to this. Instead, Franks dropped the 173rd Airborne Brigade and Special Forces teams into northern Iraq, where they linked up with friendly Kurdish militia units to tie down substantial Iraqi forces.

Gen. Tommy Franks, the coalition commander, devised a bold invasion plan that depended upon speed, firepower, technology, and the lethality of American weapons. His objective was to reach Baghdad and destroy Saddam’s regime as quickly as possible. He made liberal use of devastating American airstrikes — what reporters called “shock and awe.” On the ground, he intended to seize and control all northerly roads that led to the capital, dash north, bypass other major cities, and avoid costly urban combat. He only had enough ground forces for a two-pronged advance. In the east, the British 1st Armored Division’s mission was to seize Basrah, the second-largest city in Iraq. He ordered the 1st Marine Division, plus other supporting Marine units, to advance north, with the intention of entering Baghdad from the east. To the west of the Marines, the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division was to advance along the western side of the Euphrates River, cross that river, and enter Baghdad from the west. Follow-up units from the 101st Air Assault Division and the 82nd Airborne Division drew the mission of mopping up any resistance that the heavily mechanized 3rd Division bypassed. Gen. Franks planned to stage another major unit, the 4th Infantry Division, in Turkey and order them to invade Iraq from the north. But the Turkish government wouldn’t agree to this. Instead, Franks dropped the 173rd Airborne Brigade and Special Forces teams into northern Iraq, where they linked up with friendly Kurdish militia units to tie down substantial Iraqi forces.

In 21 days, coalition forces overran Iraq and captured Baghdad. Saddam’s regime collapsed like a house of cards. Iraqi resistance to the invasion was mixed. Some units surrendered in droves. Others simply vanished as soldiers threw away their uniforms and went home. Other formations, particularly Fedayeen Saddam and Republican Guards, fought desperately, even in suicidal fashion. Plus, thousands of foreign fighters from all over the Middle East filtered into Iraq to fight the coalition. These men were usually poorly trained but fanatical Muslims who didn’t like the idea of an Anglo-American army conquering Islamic soil.

The invasion succeeded, but it was no walkover. American troops had fought bitter, costly battles at such places as An Nasiriyah, An Najaf, Baghdad International Airport, and in Baghdad itself. By the end of April 2003, the fighting in Iraq had mostly died down. Even though no formal surrender of Saddam or his regime had taken place, to most Americans the war seemed to be over.

A long, grim struggle: The counterinsurgency phase

Franks’s war plan was well designed for the limited objective of overthrowing Saddam’s government and destroying the conventional Iraqi armed forces. But the larger issue was the fate of post-Saddam Iraq during the ensuing coalition occupation. Franks and his superiors in the Pentagon and the White House made few concrete plans for this more complicated mission. This was a fatal oversight. With an invasion force of only about 250,000 troops, the coalition couldn’t hope to maintain security and keep control over the whole country. Even before the war, a host of media, military, and political critics had said the invasion would require a much larger force. But Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld believed that large armies were a thing of the past. He argued that American swiftness and technology, especially airpower, would allow a moderately sized army to subdue and occupy Iraq.

As it turned out, he was dead wrong. Throughout 2003, American ground forces in Iraq struggled to maintain order in a country that seethed with ethnic, religious, and economic tensions. When the Americans killed Saddam’s sons in July and captured the dictator himself in December, it hardly affected the situation in Iraq. Almost overnight, a variety of violent insurgent groups came into being, waging guerrilla war against the Americans, who were shocked and unprepared for this kind of war. Soon, the number of U.S. casualties exceeded those suffered during the invasion phase. Sadly, that trend would only get worse in the months and years to come. As the violence grew worse and the casualties mounted, the war grew increasingly unpopular with the American people. As of 2007, more than 3,700 Americans had died in the Iraq War.

The failure of Rumsfeld’s 2003 Iraq invasion plan can, to some extent, be attributed to numbers. For instance, during Desert Storm, the anti-Saddam coalition employed a force of nearly 700,000 soldiers for the limited objective of expelling Iraqi forces from Kuwait. In 2003, the smaller “coalition of the willing” drew on less than half that number for the much more ambitious objective of destroying Saddam’s regime, occupying Iraq, and converting it into a model democracy. Rumsfeld’s biggest mistake was his failure to understand the historical importance of ground combat power in winning wars.

The failure of Rumsfeld’s 2003 Iraq invasion plan can, to some extent, be attributed to numbers. For instance, during Desert Storm, the anti-Saddam coalition employed a force of nearly 700,000 soldiers for the limited objective of expelling Iraqi forces from Kuwait. In 2003, the smaller “coalition of the willing” drew on less than half that number for the much more ambitious objective of destroying Saddam’s regime, occupying Iraq, and converting it into a model democracy. Rumsfeld’s biggest mistake was his failure to understand the historical importance of ground combat power in winning wars.

Struggling for security

By 2004, the Americans were focused on creating a new Iraqi government and army, to further the goal of a strong, peaceful, economically stable Iraq. But this would take time. In the meantime, American soldiers struggled mightily to maintain order and quell the daily violence that plagued the country. Thus the conflict raged on, year after year, into 2008. A dizzying variety of insurgent groups engaged in daily attacks, sometimes against one another, often against American soldiers.

Iraq is home to three major groups, none of whom particularly like one another. Sunni Arab Muslims comprise about 20 percent of the population, mostly in the western part of the country. They were traditionally the ruling class, especially under Saddam. Non-Arab Kurds comprise another 20 percent, and they live primarily in the north. The Kurds tend to be pro-American, but some want their own country, separate from Iraq. About 60 percent of Iraqis are Shiite Arab Muslims. They dominate the south and Baghdad. Sunnis and Shiites despise each other passionately because of theological and political hatreds that go back hundreds of years.

Iraq is home to three major groups, none of whom particularly like one another. Sunni Arab Muslims comprise about 20 percent of the population, mostly in the western part of the country. They were traditionally the ruling class, especially under Saddam. Non-Arab Kurds comprise another 20 percent, and they live primarily in the north. The Kurds tend to be pro-American, but some want their own country, separate from Iraq. About 60 percent of Iraqis are Shiite Arab Muslims. They dominate the south and Baghdad. Sunnis and Shiites despise each other passionately because of theological and political hatreds that go back hundreds of years.

Anti-American Islamic groups in neighboring Syria, Iran, and Saudi Arabia exacerbated the problems in Iraq by sending weapons, money, and plenty of committed fighters across the borders into Iraq. The insurgent opposition to the coalition, though diverse, can be boiled down into three categories:

Sunnis who want to evict the Americans and return to prominence in the country.

Shiites who hate Americans as invaders and infidels. As representatives of the majority group in Iraq, these Shiites feel control of the country should rightfully be theirs. They also yearn to settle old scores with their former Sunni oppressors.

Foreign fighters, particularly anti-American Al Qaeda insurgents whose goal is to create a world-dominating Islamic fundamentalist empire.

For the volunteer, professional American troops who served in Iraq, the war was a seemingly never-ending commitment. Soldiers, Marines, sailors, and airmen served tours of duty ranging from 7 to 15 months. Many served multiple tours. For the soldiers on the ground, the war consisted of a range of experiences. Sometimes they fought pitched battles with insurgents as at Fallujah in 2004 or Tal Afar in 2005. More commonly, the enemy avoided such conventional battles. So soldiers and Marines patrolled an area of operations, trying to help the locals, provide for their security, and hunt down insurgents. All the while they had to be wary of insurgent ambushes, deadly improvised explosive devices on the roads, suicide bombers, and sniping. Soldiers and Marines patrolled in vehicles and on foot, in temperatures that often exceeded 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Those who served in Iraq could never forget the shimmering waves of heat, the pungent stench of raw sewage that pervaded much of the country, or the grinding poverty of many Iraqis. The soldiers also couldn’t forget the strange duality of serving in Iraq. One minute they could be handing out candy to children or chatting amiably with local folks. The next minute they could be in grave danger from an insurgent attack. In Iraq, an American never can be sure where and when such danger may lurk.

For the volunteer, professional American troops who served in Iraq, the war was a seemingly never-ending commitment. Soldiers, Marines, sailors, and airmen served tours of duty ranging from 7 to 15 months. Many served multiple tours. For the soldiers on the ground, the war consisted of a range of experiences. Sometimes they fought pitched battles with insurgents as at Fallujah in 2004 or Tal Afar in 2005. More commonly, the enemy avoided such conventional battles. So soldiers and Marines patrolled an area of operations, trying to help the locals, provide for their security, and hunt down insurgents. All the while they had to be wary of insurgent ambushes, deadly improvised explosive devices on the roads, suicide bombers, and sniping. Soldiers and Marines patrolled in vehicles and on foot, in temperatures that often exceeded 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Those who served in Iraq could never forget the shimmering waves of heat, the pungent stench of raw sewage that pervaded much of the country, or the grinding poverty of many Iraqis. The soldiers also couldn’t forget the strange duality of serving in Iraq. One minute they could be handing out candy to children or chatting amiably with local folks. The next minute they could be in grave danger from an insurgent attack. In Iraq, an American never can be sure where and when such danger may lurk.