WHAT LIES BEHIND THE STUDY OF ASTRONOMY AT HOGWARTS?

Astronomy plays a dramatic but subtle part in the storylines of the Harry Potter series. It’s against the backdrop of a full moon, of course, that we first see Remus Lupin, also known as Moony, transform from half-blood wizard into a werewolf in the Prisoner of Azkaban. It’s the lunar light that triggers Lupin’s lycanthropy.

The enchanted ceiling of the great hall at Hogwarts has been known to conjure up astronomy at night. A reflection of the sky above, the ceiling seems to zoom in on star clouds and swirling galaxies, as if trying to better Hubble.

And the astronomy tower, the tallest tower at the castle, is the setting for one of the series’ most dramatic scenes. Under the gathering darkness of the death eaters’ dark mark, lurking high above the tower, Dumbledore meets his death from a killing curse, cast by Severus Snape. But the astronomy tower is also where the students study. At midnight, under the stewardship of Professor Aurora Sinistra, they gaze at the planets and stars through their telescopes. So, what use is astronomy to wizards and witches in the Hogwarts curriculum?

Moons and Planets

Knowledge of the phases of the moon might come in handy. As werewolves transform under a full moon, knowing when the phases occur, no matter where in the world you are, would be useful for a wizard wishing to avoid lycanthropes. As for the planets, they define the very days of the wizarding week. In Latin, they run Sunday to Saturday as follows: Solis (sun/Sunday), Lunae (moon/Monday), Martis (Mars/Tuesday), Mercurii (Mercury/Wednesday), Iovis (Jupiter/Thursday), Veneris (Venus/Friday), and Saturni (Saturn/Saturday). As you can probably see, even in English, some of the planetary days remain: Sunday, Monday, and Saturday, still bearing the mark of sun, moon, and Saturn respectively in their names.

It seems the Hogwarts curriculum also required its students to learn and understand the movements of the planets. Such a study of the planets is not without a peculiar brand of British humor. Witness an encounter with the outer solar system in which Professor Trelawney, peering down at a chart, declares to Lavender Brown, “It is Uranus, my dear,” only to hear Ron reply, “Can I have a look at Uranus, too, Lavender?” And Hermione’s correction of Harry’s understanding of Jupiter’s moon, Europa, “… I think you must have misheard Professor Sinistra, Europa’s covered in ice, not mice.”

But much can be learned from even the merest mention of detail in the stories. Take, for example, the fleeting allusion in the Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone scene where Hermione tests a reluctant Ron on astronomy, while Harry pulls a map of Jupiter toward him and begins to learn the names of its moons. In Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, all three deal with a difficult essay on Jupiter’s moons.

Tipping Point Cosmologies

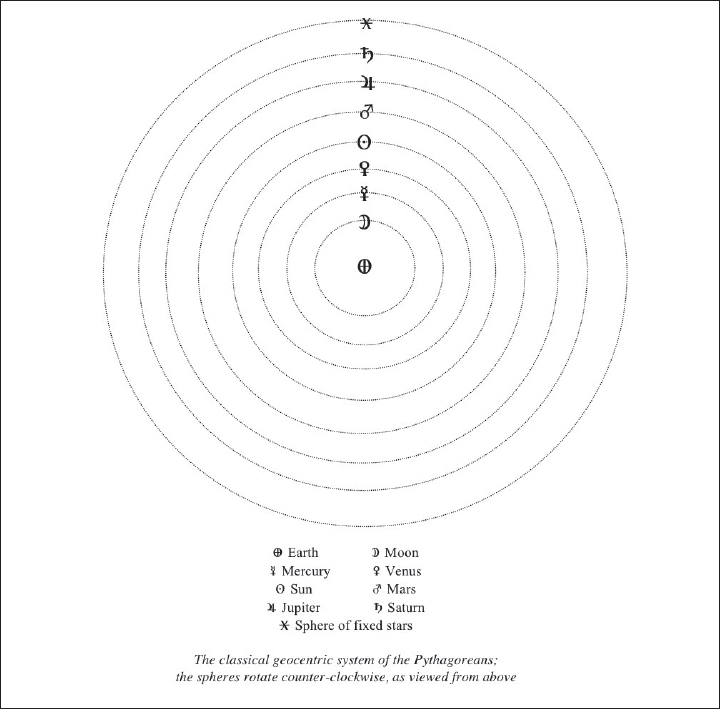

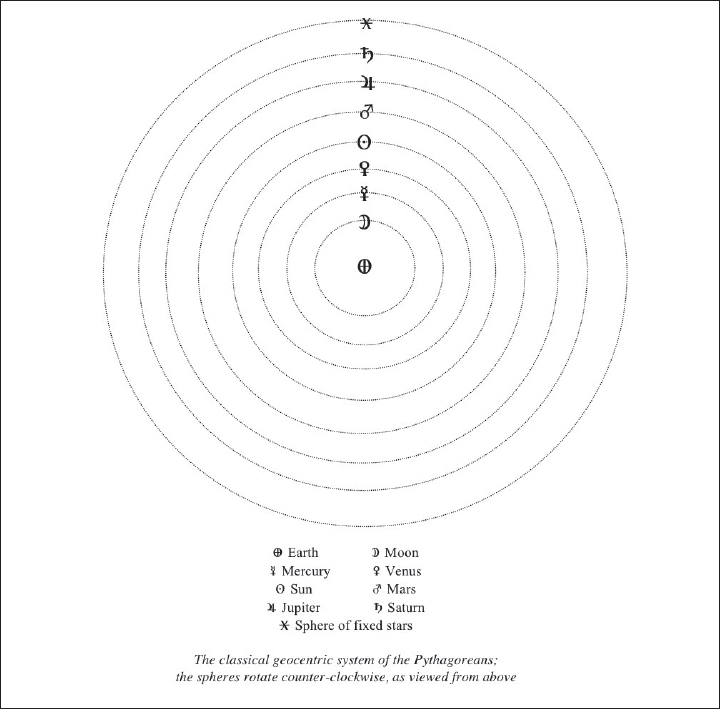

The history of astronomy, like magic, is a long one. And for much of that history, the focus was the movement of the planets. One system, the geocentric system, puts the Earth at the center of the ancient universe. The planets speed in circular orbits about the central Earth. This scheme gives a good account of the sun’s behavior on its yearly journey through the zodiac and the seeming path of the sun across the sky. The geocentric system also gives a reasonable account of the rather less regular motion of the moon. But the plain circular orbits come nowhere near explaining the observed motions of the wandering planets.

The geocentric system of Aristotle and Ptolemy

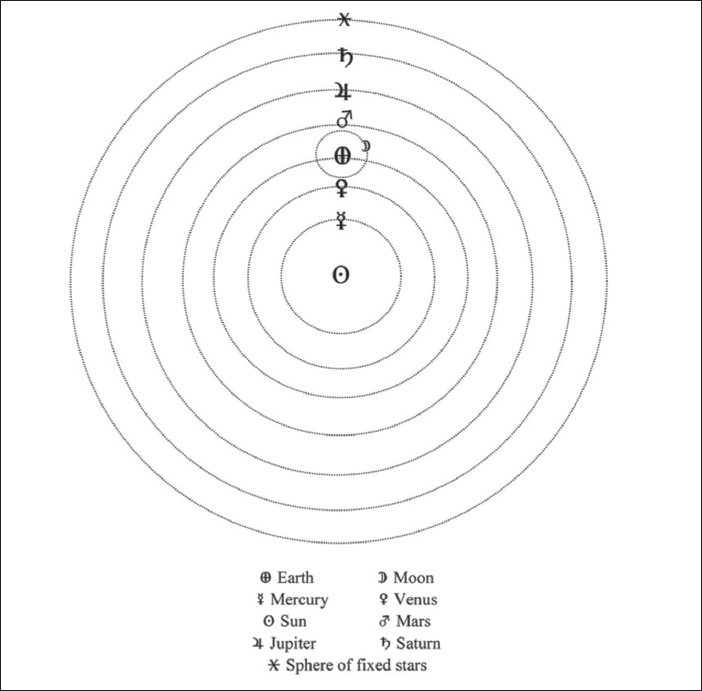

Pitted against the geocentric planetary system is the sun-centered, heliocentric cosmology. Here, the sun and its attendant planets are set out in their true heavenly order. The heliocentric system also explains the curiosity of the apparent movement of the planets. Such movement can only be understood when you know that the Earth itself is a moving planet. In the geocentric system, Earth is no mere planet, but the center of the entire universe.

The movement of the planets was the tipping point for your cosmology of choice. Both systems have been known since ancient times, but the mercurial events of the medieval period pushed an obscure Polish cleric, Nicolas Copernicus, to re-launch the heliocentric system in a book that would change history. Copernicus’s book, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), was published in 1543. Its appearance meant the eventual defeat of the ancient and long-accepted geocentric system—but not without controversy.

The heliocentric system of Copernicus

The Darkness Rising

The medieval church had supported the geocentric system. It placed man midway, between the inert clay of the Earth’s core and the divine spirit. Man could either follow his base nature down to Hell, at the center of the Earth, or follow his soul and spirit, up through the celestial spheres to the heavens, so the system of planets became tied up with the medieval drama of Christian life and death.

To shift the Earth was to move the throne of God himself, who was meant to reside beyond the sphere of the fixed stars—and yet shift the Earth is exactly what Copernicus did. His new planetary system, and the theories it inspired about a boundless new universe teeming with planets, gravely disturbed Western philosophy and religion. Heliocentrism demoted the Earth from the center of the universe. It raised doubts about articles of Christian faith, such as the doctrine of salvation and the conviction of divine power over all earthly matters. And it called into question the nature of creation, and its relation to the creator. In short, Copernicanism raised doubts that were of fundamental importance to human, albeit muggle, identity.

The World Turned Upside Down

Then, there was Galileo. Italian mathematician Galileo Galilei wielded the newly invented telescope like a weapon of discovery and the new universe was unveiled. Galileo found Earth-like mountains and craters on an imperfect moon. Impure spots on the sun. Countless stars, worthy of adorning Dumbledore’s cloak, which could only be seen with the aid of the spyglass. So much for the perfection and immutability of the heavens.

Galileo’s most shattering discovery was the main four moons of Jupiter. They were proof of a focus of gravitation other than Earth. The old system had it that only the Earth acted as such a center. And when Galileo invited the great and good to peer at the moons through the spyglass, not one among the eminent guests was convinced of their existence. Some were so blinded by prejudice, they even refused to look down the tube. Galileo’s optic tube shattered the old universe.

That battle was won with Galileo’s discovery of these new worlds. It sparked the Scientific Revolution. It marked the paradigm shift of the old universe into the new. The cozy old geocentric cosmos was about man. The new universe of Copernicus and Galileo was decentralized, dark, and infinite. This is what sits behind the study of Jupiter’s moons in the Hogwarts curriculum, and this branch of astronomy places the wizards in the progressive camp in the battle of the cosmologies.