COULD SCIENTISTS BE THE MODERN WIZARDS?

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

This quote comes from Arthur C. Clarke, the British futurist writer, maybe most famous for co-writing the screenplay of the 1968 movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, widely thought to be one of the most influential films of all time. The quote is one of Clarke’s famous Three Laws, the other two of which are also relevant to thoughts about magic: “When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong,” and, “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.” So, does Clarke’s famous Third Law make scientists modern wizards? To answer this question, it’ll help to consider the relationship between magic and science.

What is science? Like magic, science is a recipe for doing certain things. And, like magic, science is ancient. It developed over many thousands of years, and passed through many cultures and societies, evolved through many metamorphoses. In classical times, science was merely one aspect of the work of the sophist. In medieval times, science was an elemental feature of the work of the alchemist, or the astrologer.

To help compare science and magic, we can think about the four pillars upon which both are based. Like magic, science is a worldview; science is an institution; science is a method; and science is a body of knowledge. To consider whether scientists might be the latter-day wizards, let’s focus on science as a worldview and a method.

Science as a Worldview

Magic and science share a common origin. Science’s worldview is one of the most powerful influences that have shaped our attitudes to the universe. It can be traced back to early forms that held some considerable sway in antiquity. Science’s tradition, which links it strongly to technique, was the knowledge passed from craftsman to apprentice, elder to novice, exists from the earliest of societies and cultures. This tradition began long before science developed as a method, discrete from everyday practice and folklore.

In early times, humans sought to control nature. The primeval world was profuse with a huge number of plants and animals, which varied widely as humans went on migratory journeys. We were parasitic on uncontrolled nature. So humans needed techniques we could use to try understanding nature, as any mistakes could often be fatal. The preservation and propagation of fire, for example, led to the very simple and essentially chemical technique of cooking. The observation of plants and the habits of animals laid the basis of biology, and the spoils of the tribal hunt would have led to a rudimentary knowledge of anatomy. But by hunting and gathering and observing, technique could only go so far.

Magic evolved to fill the gaps left by any early limitations in technique. Humans used animals as magic totems. The tribe would use images of the totem, or maybe symbols and even dances, to encourage the animal to prosper and multiply. A human animagus, we might call them early magicians, would essentially become the animal. As long as the rules of the totem were followed, the tribe would flourish.

The totems became associated with certain powers. Perhaps they were sacred, or taboo. They had to be handled carefully, or else the balance of nature would be upset. The totem carried a certain mana, or power, which signifies its influence over humans. Such totemic symbols exist to this day, in the lion of Gryffindor, the serpent of Slytherin, the badger of Hufflepuff, and the eagle of Ravenclaw.

Theory of Magic Spirits

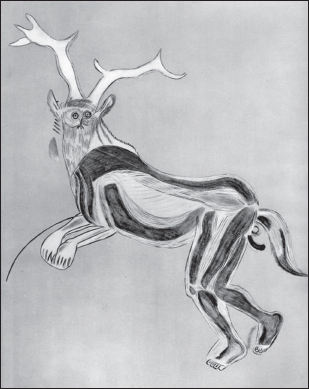

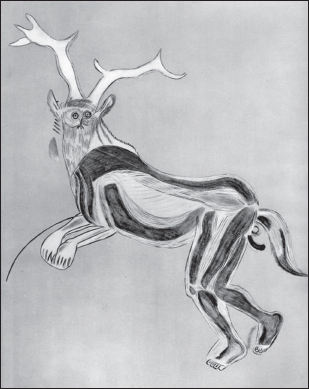

The methods of the early magicians were based on mimicking and sympathizing with the workings of the universe. Based on archeological evidence of the cave art of Western Europe, it seems these magicians were already established in the Old Stone Age. Take the cave paintings of the Trois-Frères in the Ariège department of southwestern France, for example. A painting there shows a magician or sorcerer wearing stag’s horns, an owl mask, wolf ears, the forelegs of a bear, and the tail of a horse. The value of such an animagi could have been to ensure a successful hunt.

The magician or sorcerer, the cave paintings of the Trois-Frères in the Ariège department of southwestern France.

At first, the magicians would use likenesses, and later symbols, to perform an operation on something that would be considered transferable to the real world. An unbroken thread links these ancient symbols to those used with such success in modern science.

Another feature of primitive thought, which at some point separated itself from imitative or symbolic magic, was the idea of the influence wrought upon the real world by spirits. The idea of a spirit probably emerged from the reluctance to accept the fact of death. Early spirits were very worldly, members of the tribe who had since passed on. But the idea evolved that it was necessary to win, or regain, the favor of a spirit, now god, by doing something that pleased them.

The old idea of spirits split into two very different forms. On the one hand, it transformed into the idea of spirit as an all-powerful being, or god, that was to become the central figure in religion. And on the other hand, the spirit became divorced from human origin to become an invisible natural agent, such as the wind, or the assumed active force behind chemical and other crucial changes. This second idea of the spirit was to become hugely important in the evolution of the understanding of spirits and gases in science.

Witchcraft to the Ignorant

Science and magic are far more entangled than you think. At first the rituals of magic would have involved most of the tribe. But, in time, cave art shows solitary figures of the tribal animagus, dressed as an animal, who appears to have some special place. In many primitive tribes today, there are still medicine men, or magicians. They are held in high esteem, as they are thought to have a peculiar relationship with the forces of nature and the universe. To some extent, they are set apart from the normal work of the tribe. And, in return, they exercise their magical arts for the tribal good. They are keepers of learning and knowledge. They are the forerunner, the lineal cultural ancestor, of philosophers and scientists.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law echoed a statement from a 1942 story by Leigh Brackett, “Witchcraft to the ignorant … simple science to the learned.” The accelerating pace of change seen throughout the 20th century and early 21st century overwhelms many. Those without science are disconnected from the science and technology of the age. To them, inexplicable science is the modern counterpart of magic, and the scientist the witch.