An abbreviation for gallon.

A liquid measure with a capacity of 231 cubic inches equal to 128 fluid ounces (3.7853 L). A common unit of measurement in the United States. One American gallon is equal to ⅚ imperial gallon.

See PRIMUS, JAN.

Either a ring-type burner located directly under the stainless steel base of the vessel being heated or a tubular burner situated inside the tank being heated and through which a flame is directed.

A piece of equipment devised by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac that is used to determine the percentage of alcohol in a solution.

It is safe to say that David Geary is the only American brewer to learn his trade in an earth-floored Scottish brewery. In the early 1980s, Geary met the Laird of Traquair, the scion of an ancient Scottish brewing family, who was visiting Portland, Maine, on business. The Laird invited Geary to work at his brewery, located in a room beneath Traquair Manor, in Peebleshire, Scotland. Geary soon chucked a sales career and headed off to Scotland.

It was there that Geary became familiar with the brewer’s craft, learning his trade using oak vessels and 17th-century brewing accoutrements. Following his stint at Traquair, Geary worked in a series of small English breweries under the tutelage of Peter Austin, a gentleman who is often considered the father of the British small brewery movement.

Geary was eager to bring his newfound knowledge back to the United States, where the microbrewery movement was in its infancy. He invited Alan Pugsley, a protégé of Peter Austin, to return with him to the United States and start a small brewery. Pugsley agreed, and D. L. Geary Brewing Co. was born. Ground was broken in 1985, and the enterprise began selling beer commercially in 1986.

Geary’s Pale Ale

A classic Yankee ale, from its lobster label to its Anglo-Saxon pedigree. This crisply drinkable beer has a firm body and a nice hop edge. “It’s a beer for drinking,” Geary says. “It’s got flavor, body, and beauty, but best of all you can drink it — and that’s the key to success.”

D. L. Geary brews a pale ale as its seasonal offering.

This is a utilitarian brewery, located in a slab-sided warehouse in a wooded industrial park on the outskirts of Portland, Maine. The brewery has a Peter Austin–designed brewhouse, a plant especially well suited for ale brewing.

D. L. Geary produces three brands: Geary’s London Porter, Pale Ale, and Hampshire Ale. The first is the company’s flagship product, the second a winter beer. Hampshire Ale is a big, malty brew, styled after an English extra special bitter. As might be expected, it is potently hopped.

See ALE BEER and MICROBREWERY.

A fining agent used to clarify beer. When added to beer, gelatin combines with tannic acid, proteins, and yeast to form a precipitate that falls out of suspension, leaving a clearer beer. Brewer’s gelatin or ordinary unflavored gelatin may be used. One tablespoon (14.79 ml) is enough to clarify 5 gallons (19 L) of beer.

See CLARIFICATION and FININGS.

Genesee is the largest independent regional brewery in the United States, with a capacity of 4,000,000 barrels. Although it does not use anything near its full capacity, “Genny” still sells a substantial amount of beer in its upstate New York and Pennsylvania markets. The company’s beers are de rigueur in taverns throughout the region, and this loyal customer base has much to do with the company’s endurance.

Genesee 12-Horse Ale

Somewhat less robust than the name suggests, but quite typical of the distinctly American-style light, golden ale. Genesee 12-Horse Ale is a fairly light-bodied beer with a smooth, malty creaminess.

The original Genesee Brewing Co. was founded in 1878 but went under during Prohibition. After the repeal of Prohibition, Louis A. Wehle opened a new firm, using Genesee’s brewing plant. The Wehle family still operates the company, which has become something of an anomaly on the American brewing scene: the largest single-plant brewing operation still in existence.

The company is one of the largest ale brewers in the United States, with a substantial part of its sales coming from Genesee Cream Ale and Genesee 12-Horse Ale. Commendably, it was one of the few breweries to persist in producing a seasonal bock beer during the 1970s and 1980s. Though available only sporadically, Genny Bock (billy goat on the label and all) is symbolic of the brewery’s commitment to tradition.

The company’s other brands include Genesee Beer, Genesee Light, and Genesee Ice. The company also owns the labels of the Fred Koch Brewery of Dunkirk, New York, and produces Koch’s Golden Anniversary Beer.

Recently, Genesee has embraced specialty beers, with products such as J. W. Dundee’s Honey Brown Lager. Most sound more special than they are, but the company has recognized the existence of the trend, and more such products are said to be in the works.

See ALE, ICE BEER, LIGHT BEER, and REGIONAL BREWERY.

German law defines starkbier (strong beer) as 15–18/1.062–1.073 OG, 5.8–7.3 percent alcohol by volume, and 20–40 IBU. Schenkbier is weaker than vollbier (regular beer), under 10.5/1.042 OG or so. Spezialbier (special or seasonal beer) is between starkbier and vollbier, at 12.5–14.9/ 1.050–1.061 OG, 5–6 percent alcohol by volume, and 5–40 IBU.

See VOLLBIER.

Pils falls within the German vollbier (full beer) category. Most people assume there is but one pilsner style. That is not the case in Germany, where beer definitions are strictly adhered to. There are four German classes of pilsner: Klassische Pilsner (Classic Pilsner); Süddeutschen Pilsner (South German Pilsner); Sauerländer Pilstypus (Sauerland Pilsner-type); and the Hanseatische Pilsenertyp (Hanseatic Pilsner-type). Pils is the only style that is brewed in every German state.

Classic Pilsner has more emphasis on hops, and is precisely crafted to be robust, have a full mouthfeel, and be well-rounded. A good German example of a Classic Pilsner is König Pilsner.

South German Pilsner is more robust and has more aromatic malt aroma than the German norm for the style. An example is Bräumeister Pils from Hacker-Pschorr in München.

Sauerland Pilsner-type is particularly light and delicate, but not very bitter at all. It is, often enough, easily identified because of its particularly light colour. Warsteiner Pils is a good example of this style.

Han is particularly bitter, dry and sharp-tasting from the hops. This North German style is mostly found around Jever. An example of this style is Jever Pilsener from Friesiches Bräuhaus zu Jever, which is owned by Hamburg’s St. Pauli Brewery.

The second step in producing malt from raw barley. After the barley is soaked in water, it is spread out in piles and allowed to sprout, or germinate, which modifies the malt.

See MALTING.

There are three types of barley germination systems.

The first is manual floor malting, the original method of germinating barley. Here grain is turned manually, allowing for air to circulate throughout and encouraging germination.

The second system is compartment malting. This is done in a Saladin box, a rectangular open-top container with a base of removable slotted plates. Grain depth may be 3 to 5 feet. The grain is turned by means of helical screws. The slotted bottom allows for conditioned air to be forced through the bed, controlling moisture and carbon dioxide content.

Germinating floors at the Anton Dreher Brewery in Budapest, Austria

The third system, Wanderhaufen, is essentially an open-ended compartment. Steeped grain is discharged into one end of the rectangular box while the grain on the “street” is moved slot by slot downward in a controlled fashion toward the awaiting kiln. Specialized turners pick up the grain and move it farther down the street, with minimum mixing of different grain lots. This system is automated, controlling temperature, airflow, and spray steeping, to provide optimum malting conditions for each type of grain.

A traditional beer made with ginger, which imparts a distinct taste and aroma. Ginger was among the many herbs and spices used by brewers to balance the sweetness of malt before the advent of hops. Commercial examples of ginger beer are almost nonexistent, although ginger is used in some holiday or Christmas ales.

See GLASSWARE.

The preferred vessel from which to drink beer. Much as with food, appreciating a good beer involves relishing its aroma, appearance, and taste. Glassware allows for a fuller sensory enjoyment. Unlike pottery or pewter, glass allows the drinker to see the beer’s color, observe the bubbles rising, and view the depth of the head. (It should be noted that beer tasters in breweries drink from opaque vessels so they can concentrate on the taste and not be distracted by the appearance.) Different shaped glasses offer different presentations of the beer’s aroma. Some glasses have wide openings that allow the drinker to place his or her nose inside the glass to better breathe in the beer’s perfume.

Since glassware does not retain flavors or odors, the drinker can better appreciate the aroma of the beer.

For Americans, the glasses of choice are the hour-glass tumblers, which have a heavy base and narrow center that flares out to a bell at the top. Also popular are straight tumblers and tall Pilsners — footed glasses that resemble narrow inverted cones.

Dimple mug

Orval’s distinctive goblet.

The Pilsner glass is a popular specialty glass in Germany because it allows for a good display of the Pilsner beers. Germans also favor glass steins; one-liter tumblers that flare at the top; wide, shallow goblets; and wheat-beer glasses, which have slender, outward curving sides and a bell-shaped top. The English prefer a straight-sided pint glass for their substantial beer, as do the Irish for their stout.

The prize for glassware variety, however, must go to the Belgians, who seem to have a different-shaped glass for each beer. (Visitors to Belgian public houses are sometimes taken aback when they order a beer and are told that all the glasses for that style are in use.) The Belgians serve tart beers in tall, narrow flutes, so the aroma rises to the nose; abbey-brewed beers in wide, goblet-style glasses that allow the beer to breathe; and Duvel beers in glasses with tulip-shaped bowls that allow the foam and beer to be consumed simultaneously. A footed tumbler with a wide bulge in the center called a Thistle glass is used for heavy, aromatic beers, and a cordial glass is used for strong ales.

Glassware is named for the beer style or the brewer. Left to right: Alt, Willibecker, Pescara Pilsner, Riedel Vinum Beer, and Weizea.

Glasses for (left to right) Gueuze, Duvel, Riedel Vinum Gourmet, Nonic “bulge”, and Standard

The crystal clearness of good glasses enhances the presentation of good beer, but the user should take caution with the care of the glassware. Beer glasses should not be washed with soap but cleaned with a sterilizing solution, since soap residue can flatten the head on a good beer. Soap residues inside bottles, as most homebrewers know, can turn the taste of the beer.

See MUG and STEIN.

Every November the bar manager and bar treasurer of the Glen Eyre Halls of Residence Club (GEHORC), a nonprofit bar run by students for the benefit of undergraduates at Southampton University, England, put on a two-day beer festival. No one seems to know how long the festival has been going on, though the Glen has been a residence hall for over 30 years. In 1995 there were over 50 real ales to sample, as well as a selection of fruit wines, four different hard ciders, and a sing-along piano player to keep things moving.

A unit in which a concentrated food-grade propylene glycol mix (40 percent propylene-glycol and 60 percent water) is chilled for circulation through cooling vessel jackets and for cold filtration. Normally fitted with a small reservoir, these units depend on a high glycol concentration and the efficiency of associated condensing units to maintain low reservoir temperatures. They may circulate glycol at 15° to 26°F (-9° to -3°C).

See CHILLING.

A multipass jacket that is wrapped around an enclosed fermenting vessel or bright beer tank to cool beer. The jacket is often located on the angled cone of a fermenting vessel or the dished bottom of a bright beer tank. It is designed for overall cooling of 20°F (6.6°C) per hour.

See CHILLING.

A drinking glass that has a deep bowl on a short stem and does not have a handle. A goblet usually holds 9 to 12 ounces (266 to 355 ml) of liquid.

See GLASSWARE.

An early English term for yeast, whose ability to change water into intoxicants inspired giving thanks to God.

In light of recent archaeological fieldwork, it appears that beer making is at least 8,000 years old. Written records go back about 5,000 to 6,000 years.

The birthplace of beer is likely to lie in Africa, although recent findings show that the peoples of the Amazon River basin of South America have been engaged in large-scale farming of fermentable grains and tubers for 8,000 years. The earliest written evidence of beer is from the ancient Middle Eastern kingdoms of Assyria, Sumer, Mesopotamia, and Babylon. Beer production is evident throughout ancient Middle Eastern society, extending through Egypt and Africa and all the way to the indigenous peoples of Latin America.

Beer was usually believed to be a gift from a goddess, rather than from a male god. This divine generosity was thought to have been prompted by pity for the plight of human beings — the only animals doomed to a life plagued by the knowledge that one day we must die.

The major goddesses responsible for giving the world its first beer were Ninkasi (the lady who fills the mouth) of Sumer and Hathor of Egypt. Menquet was another Egyptian goddess of beer. Some confusion exists over the gender of Bes, a grotesque dwarf deity from the Sudan, adopted by the Egyptians as a beer god/goddess and the protector of children and women in labor. The ancient goddess Ishtar had many beer associations, particularly among the Assyrians.

The goddesses of brewing survive to this day among isolated tribal groups in Africa and India. All brewing is accompanied by prayers and offerings to the earth goddesses Mama Sara and Pauchua Mama, both of whom date back long before the rise of Incan civilization.

Just as goddesses are universally believed to have given humans the gift of beer, women historically have been the brewers of beer. It is obvious that women used their brewing skills to maintain power and status in male-dominated hunter-gatherer societies. In remote corners of the modern world, women continue their domination of beer making.

Supernatural beings were often associated with beer and wine, as this 16th-century print of an angel holding a goblet indicates.

Wherever female spirits influenced their daughters in the making of beer, brewsters returned the favor by offering as a sacrifice small quantities of every brew. South American Indians continue to pour a small amount of beer to the ground before tasting it, in acknowledgment of these spirits.

See AZTEC BEER GODS, BES, and NINKASI.

The Vanneste family has brewed beer in Bruges, Belgium, for more than 200 years. Paul Vanneste, the current brewmaster, has devoted his efforts to maintaining his family’s and city’s brewing traditions. As a result, Brouwerij de Gouden Boom is part museum and part brewery.

In its capacity as a brewery, Gouden Boom produces several noted wheat beers, including Blanche de Bruges, a spicy, fruity beer that is bottle-conditioned. The brewery exports to North America, where its beers are handled by Vanberg & DeWulf of Cooperstown, New York.

See WHEAT BEER.

The current Gouden Carolus was founded in 1905, although the beers it produces have much longer histories. This brewery’s best-known product is Gouden Carolus, known in its home market as Carolus D’Or (Golden Charles), a name that refers to Emperor Charles V, who grew up in Mechelen. This beer has been brewed since 1369. The company also brews Mechelschen Bruynen and Triple Toison D’Or. Gouden Carolus is imported to the United States by Phoenix Imports of Ellicott City, Maryland.

See ALE and BOTTLE-CONDITIONED BEER.

Gouden Carolus

A rich, dark ale made from pale and dark malts and a proportion of wheat. Brewer’s Gold and Saaz hops (grown in Belgium) are used, together with orange peel and coriander. The beer is brewed to an original gravity of 1.076, with an alcohol content of 7.0 to 7.8 percent by volume. It is a rich, powerful beer with a delicious malty aroma. Hints of prune and peach are evident in the flavor, which is very smooth and sweet. Gouden Carolus is bottle-conditioned and is said to benefit from several months’ storage.

The precleaner is a piece of equipment set up to remove both coarse impurities and fine impurities from barley being received at the malthouse from the farm. Grain passes through a coarse sieve to remove impurities such as straw, earth, and stones. It then passes through a fine screen that removes fine particles such as sand and seeds. The grain flow is accompanied by an airflow, to help remove dust and very light particles.

The cleaner is a piece of equipment generally comprising a rotating metal cylinder with indentations on the inner face, sized to catch particulate matters smaller than whole grain kernels, which automatically drop out. Half kernels, seeds, and the like are caught here and rejected. The barley is then graded to size, with the machine generally sieving out grains less than 2.2 mm (0.09 inch) in width. Grading screens oscillate to and fro, separating the different grain sizes.

Grain must be cleaned of impurities such as straw, stones, and sand before it can be used.

Superior Belgian beers. Grand Cru, meaning “special vintage,” is really the brewer’s favorite or “best” beer. It is most often used for special occasions, such as weddings, victory celebrations, grand openings, and such. It is used much the way champagne is used in other countries. Grand Cru is brewed in smaller quantities than other brands of the same brewery.

Tim Webb, in the Good Beer Guide to Belgium and Holland (CAMRA Books) says this about Grand Cru/Cuvée:

“The terms ‘cuvée’ and ‘grand cru’ are frequently applied to a wide variety of beers in Belgium and the Netherlands. However, the terms … say nothing about the beer in the bottle except to imply that it will be expensive.

“The term ‘Cuvée’ is commonly used in the names of label beers, regular brewery ales, which are masquerading under a false name for a particular distributor. One Dutch bar owner told the Guide that ‘grand cru’ means ‘big crutch,’ and is used either to suggest machismo or else because the beer is so puny that it needs extra support!

“The Guide uses neither term in classifying a beer’s style.”

It would be very easy to simply toss these into the strong ale category, but there is a problem: the labeling. It is preferable to retain this category but point out that these beers are, indeed, strong ales. Since many Grand Crus are aged for prolonged periods, it wouldn’t do them justice to simply toss them into the general “strong ale” category, where, perhaps, they might get lost or marginalized.

A small vessel or trough to which wort is directed from the mash tun for visual and hydrometer inspection. Wort may be recycled back to the mash bed for clarification. This is known as Vorlaufvehrfahren.

See YAKIMA BREWING & MALTING CO.

See DENSITY.

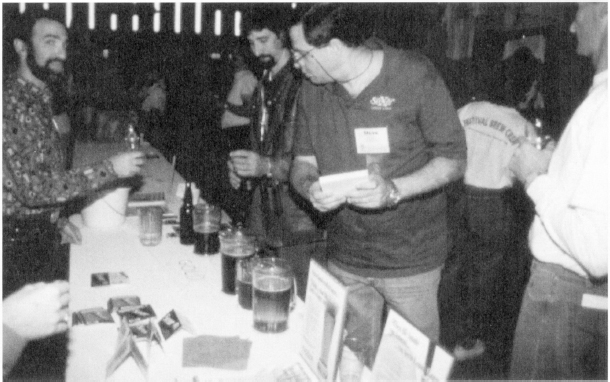

The Great American Beer Festival (GABF) is North America’s largest beer festival, a smorgasbord of suds that is the ne plus ultra for beer fans, the Super Bowl of brew fests — which may be why it is now promoted with Roman numerals attached. At the 13th (or XIIIth) festival in 1994, about 20,000 visitors to the 2-night gala in Denver’s Currigan Exhibition Hall encountered the staggering tally of more than 1,100 beers from 263 American breweries.

A 2-day blind tasting of beers by a professional panel is held prior to the public tasting. In 1994, the seventh year of the professional panel, 50 judges tasted beers from 42 states in 34 style categories. No best of show is selected, but gold, silver, and bronze medals are awarded for the top three finishers in each category.

The GABF is put on by the Association of Brewers, a nonprofit association that grew out of the American Homebrewers Association. The association serves as a resource for anyone wishing to get involved in smaller-scale brewing, which is virtually the only way anyone starts brewing these days, and the GABF is its blowout extravaganza. It is also great fun, but founder Charlie Papazian cautions that the association “goes to great lengths to make sure people do a responsible job. It’s not a drunken spree at all. People go there to taste and talk about the beer and discover new favorites.”

Papazian has been known to go so far as to call the festival “educational,” and there are numerous displays of brewing techniques, cooking demonstrations, book signings, and the like. It helps to bring an empty knapsack, as there are piles of literature to cart away, as well as beer coasters, labels, buttons, and crowns. But the wondrous profusion of beers is the real draw. The bulging menu includes a lot of splendidly obscure names of distinctively flavored beers: El Toro Oro Golden Ale, Mirror Pond Pale Ale, Untouchable Scotch Ale, Pyramid Apricot Ale, Harvest Moon Pumpkin Ale, Sea Dog Oktoberfest, Heavenly Hefe Weizen, Whitewater Wheat Ale, and Big Nose Blond.

The early festivals were smaller and funkier, which may be true of the entire microbrewery industry. Dan Bradford, now publisher of All About Beer magazine, directed the GABF for 10 years. “When I began, the festival had twenty-two breweries and a couple hundred of my close friends attended,” he said. “Beer, right now, is one of the most exciting things going on for those interested in quality, in food, and in a certain lifestyle. It’s intriguing to learn about the various components, the stylistic variety, the difference between an ale and a lager, and the like. But it’s easy to learn about and discuss without being a snob, the way talking about wine puts off many people, or single malt whiskeys, which are so obscure there isn’t anyone you can talk with about them. Hence the draw.”

The professional panel was instituted alongside of, and then in place of, a consumer preference poll of the early years. The poll was rarely free of controversy, especially when critics claimed Samuel Adams kept winning the best beer award because it gave away more free beer paraphernalia than any other brewery.

Each year the GABF attracts crowds of as many as 20,000 beer lovers.

Back then, it was no great difficulty to sample all the new beers one had never tried. Now there are logistical problems: One-ounce servings of 1,200 beers comes to 1,200 ounces, or 9.375 gallons of beer — a hard night’s work. Even over the 2 nights of the festival, 9-plus gallons would be stretching all sorts of gustatory, legal, and biological limits.

It helps to have a tasting plan. One might drink only porters, pale ales, beers with fruit in them, or beers named after animals. Beers with goofy names might work. In addition to the brands listed above, in 1994 the goofy name list would have included What the Gentleman on the Floor Is Having, Moose Juice Stout, Three Blind Monks, Doggie Style, Duck’s Breath Bitter, and Chicken Killer Barley Wine.

See ASSOCIATION OF BREWERS and GREAT BRITISH BEER FESTIVAL (GBBF).

For the lovers of fine real ale, the 5-day Great British Beer Festival (GBBF) is Mecca. Despite a national rail strike in 1994, 45,000 pilgrims braved hot and muggy weather to find that the English know how to keep beer in its best condition no matter what the circumstances.

GABF beer-style guidelines, established yearly, are the industry standard.

This was the 17th annual festival sponsored by the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), offering up to 300 cask-conditioned ales at the Grand Hall Olympia in Kensington (England), poured into roughly 182,000 pints. (Visitors buy pints or half-pints at the GBBF, as opposed to the normal American practice of pouring 2-ounce samples for tasters.)

Despite justifiable pride in the English ales, the festival is not chauvinistic. More than 100 imports, mostly specialty beers, were poured at the Foreign Beer Bar, and hard ciders and perries also were available.

A good deal of the excitement of the festival takes place before the doors are opened to the public. A panel of beer judges picks the Champion Beers of Britain. Beers from breweries at least two years old are nominated by CAMRA members and then grouped into eight categories (six beers to a group): Mild, Bitter, Best Bitter, Strong Bitter, Porter/Stout, Old/Strong Ale, Barley Wine, bottle-conditioned Beer. From the winners in these categories, a Best of Show is chosen (the bottle-conditioned beer is not eligible). As might be expected, the winning beer makes full use of the marketing advantages for the following year.

The winners are announced at the beginning of the festival, so festival-goers are quick to swarm around them before going on to pick their own best of show.

Attendance at the GBBF has been steadily growing. The 1994 figures showed an increase of 8,000 visitors, with a concomitant growth in the volunteer staff to 750. Organizer Christine Cryne does not expect those numbers to shrink. “Real ale is growing in popularity, and a wider range of people are drinking it,” she says. “The 1994 event demonstrated this very clearly. In particular, we saw dramatic proof that more women are turning to good beer.”

The GBBF is but one of several festivals organized by CAMRA throughout England. Contact CAMRA for current information about other upcoming festivals.

See CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE (CAMRA) and SCOTTISH BEER FESTIVALS.

Formerly the Victoria Microbrewery Festival, sponsored by the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) Victoria, the Great Canadian Beer Festival is the north country’s largest tasting of microbrewed beers. The 1994 festival attracted more than 3,200 visitors. According to festival chairman John Rowling, “We are taking advantage of the increasing interest in new beer products offered by the numerous microbreweries in western Canada and the northwest United States, and of Victoria’s growing reputation as a beer tourist destination. Victoria is listed in Jack Erickson’s Brewery Adventures in the Wild West as one of the ten western North America ‘brewery adventure’ cities.”

The 2-day annual festival showcases Victoria as the British Columbia beer capital, but plenty of other Canadian brewers are represented as well. United States beers also are not neglected. CAMRA Victoria asks each brewery to send at least one representative to tend its festival booth.

The festival offers the usual food booths, T-shirts and promotional materials, and musical entertainment. Exhibitors include maltsters, hop growers, glassware companies, and even the Royal British Columbia Museum. CAMRA Victoria is a 200-member offshoot of the 45,000-member CAMRA of the United Kingdom.

See CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE (CAMRA).

The inaugural Great Eastern Invitational Microbrewery Festival, held at and sponsored by the Stoudt Brewing Company in Adamstown, Pennsylvania, took place in 1992. Only 14 breweries were present for the two-session festival, but even so traffic was a problem. The wrinkles have now been ironed out, and the Great Eastern has become one of the more popular beer events east of the Mississippi for attendees and brewers alike.

Carol and Ed Stoudt send brewers invitations to the festival, which is now broken up into three 4-hour sessions (one session on Friday night and two on Saturday). About 1,000 beer fans attend each session. Every attendee receives a souvenir glass and as many 2-ounce pours as he or she desires. A ticket also entitles the bearer to indulge in “The Best of the Wurst,” a meal consisting of wurst, German potato salad, and beer bread. Naturally, the Stoudt brewery store remains open for souvenirs and champagne-size bottles of Stoudt beers.

Adamstown is located midway between Lancaster and Reading, and the Stoudt sprawl is now a magnet for antique hunters, country dancers, and beer aficionados. Ed Stoudt says that the brewery complex “is all just a natural progression of our interests.” The progression began with a small steak house opened in 1962 and evolved into a virtual amusement park of gemütlichkeit and breweriana. The festival is held in a genuine beer garden — a roofed but open-air brewery hall — where the Stoudts hold their own smaller-scale brew fests throughout the summer. The couple can often be found presiding at a massive wooden table in the traditionally private Stammtisch area of the brewery hall, fenced off for the family but basically open to the festivities.

Carol runs the brewery end of the operation. “We want brewers to like the event,” she says, “so we don’t want to make it cost-prohibitive.” The Stoudts put the brewing reps up at a local hotel and feed them between festival sessions. Well over 50 beers from top East Coast microbreweries are served. The festival’s success led the Stoudts to create the annual Great Eastern Oktoberfest as well.

Sponsored by the Little Shop of Hops and the Beer & Tavern Chronicle, the Greater New York Beer Expo debuted at the Jacob Javits Center in 1993 and has since moved to the New York Coliseum.

See SUMMIT BREWING CO.

This invitational festival brought 40 brewers with 400 kegs to Seattle’s Exhibition Hall in 1994 and was produced by Festivals Inc. The festival’s beer sale proceeds went to the nonprofit Culinary Arts Promotions Association, whose members acted as volunteer pourers.

See NORTHWEST MICROBREW EXPO.

From the producers of the Boston Brewers Festival, the first Great Southern Brewers Festival was held in 1995 at the North Atlantic Trade Center in Gwinnett County, Georgia, just outside Atlanta. As at the Boston festival, the promoters planned two 4-hour sessions at the Lakewood Exhibition Center, with 40 craft brewers supplying 100 different beers to an estimated attendance of 10,000, each given a souvenir tasting glass, an event and tasting program, and musical entertainment. No beer competition was planned.

See BOSTON BREWERS FESTIVAL.

Mitch Gelly, 1995 president of the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild in Wisconsin, said, “For the ninth year of the Great Taste of the Midwest festival we got close to 50 brewers from throughout the Midwest. It’s a nice, usually a small, crowd, and 95 percent of the breweries that attend are staffed by the brewmasters or the immediate staff. So it’s the people who are actually making the beer, not just representatives doing the pouring. That’s nice for a public tasting.”

The annual 1-day event is held early each August, at the Olin-Turville Park in Madison. In 1994 there were 1,500 attendees and 35 breweries serving about 100 different beers. A crowd of 2,000 people and samplings of 130 to 140 beers were expected for 1995.

Coarsely ground grain used to brew beer. Can also refer to (1) the amount ground at one time, (2) sieved and ground barley or wheat malt that is ready for mashing, or (3) a quantity of barley (or barley and wheat malt) sufficient for one mashing.

Grain needs to be coarsely ground before it can be used to brew beer. The grain is not, however, as finely ground as flour.

A mild steel case that holds crushed grist from the mill prior to mashing. A control slide at the base of the chute controls the flow in situations where milling and mashing occur simultaneously (desirable in microbrewing). When milling and mashing occur at the same time, the mill hopper serves as a grist case, holding uncrushed grains.

A potent brew made in anticipation of and preparation for the birth of a child. In Europe and the American colonies, groaning beer and groaning cake were served to midwives and mothers in labor. The sustaining benefits of ale were considered essential to the health and survival of both infant and mother, who was encouraged to drink copiously during childbirth.

An American slang term for a pitcher or pail in which beer was carried home from the saloon. “Rushing the growler” referred to repeated trips back to the saloon for refills. Children were most often sent on these beery errands.

A mixture of herbs and spices used as flavoring and bittering agents before being replaced by hops. Gruit (also known as grut, gruyt, grug, and gruz) was made from aniseed, wild rosemary, caraway seeds, coriander, cinnamon, ginger, juniper berries, milfoil, nutmeg, sweet gale, and yarrow.

See LAMBIC.

Arthur Guinness acquired the St. James’s Gate Brewery in Dublin, Ireland, in 1759. Guinness’s genius and brewing skill refined the sweetish dark beer style known as porter into the classic example of bitter, roasted malt stout.

Somewhat more than 200 years later, the Guinness Brewing Group continues to operate St. James’s Gate and has 13 other plants. Guinness brands also are brewed under license in 23 countries.

The principal product of the Guinness Brewing Group is, of course, Guinness Stout. The origins of the drink date back to the early 19th century, when Guinness was a porter brewery. The company named one of its stronger porters Guinness Extra Stout Porter. Eventually, the porter appellation was dropped, and the rest is history.

In the years since its creation, Guinness Stout has been mentioned more often than any other beer in poems, songs, novels, and short stories by authors great and small. The cocktail Black Velvet, a wondrous drink made of champagne and Guinness, was a favorite of the German statesman Otto von Bismarck. Black Velvet was first served in observance of the death of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, in 1861. The champagne portion stood for the nobility, and the Guinness represented the commoners, who adored Albert.

The famous black beer makes for a curious world beer, but that is what it has become, carving a niche for itself from the pubs of Dublin to the sweltering tropics half a world away. Guinness Stout is now the most cosmopolitan of beers, sold in 120 world markets.

The Guinness Stout served in the Caribbean is not precisely the same as that served in Ireland, as the Dublin brewery makes half a dozen formulations, including pasteurized and unpasteurized draught; pasteurized and unpasteurized bottled; a strong bottled Guinness for European markets; and a somewhat different strong bottled product for tropical climes (the famous Foreign Extra Stout). In the United States, consumers get a pasteurized draught, served using a proprietary nitrogen–carbon dioxide system, and a bottled product brewed using some proportion of adjunct grains. The various stouts range in original gravity from 1.039 for draught to 1.073 for the strongest bottled versions.

During and after World War II, Guinness Stout was brewed in the United States at the Burke Brewery in Long Island City, New York. The arrangement, begun in 1939, was made so that the supply would not be interrupted by U-boats. After the war, it turned out that Guinness drinkers were chauvinistic enough to want their stout from the source — St. James’s Gate — not Long Island City. The licensing agreement was terminated in 1954. Today Guinness Stout is imported into the United States by the Guinness Import Co. of Stamford, Connecticut, and Guinness PLC operates a corporate office in London, England.

Guinness Stout

Guinness used a “Guinness Is Good for You” ad campaign for years. Prominent in their advertisements were testimonials from physicians singing the praises of Guinness as a healthful tonic. Given current medical evidence, these doctors may not have been far off the mark. Whether Guinness is therapeutic or not, draught Guinness is one of the most aesthetically pleasing beers around: black in the glass, topped with a stark white head. Easy on the eyes, Guinness is also easy on the palate: roasty, smooth, and creamy almost to a fault.

Unfermented wort. The term is usually used in conjunction with the kraeusening process. Before adding yeast and fermenting the wort, a small amount of wort is reserved as a priming agent. This reserved wort, or gyle, is carefully stored in a sanitized container and usually refrigerated to prevent it from being spoiled by wild yeasts or bacteria. Once the fermentation is complete, the gyle is added back into the beer, and it is bottled. It is used at the rate of about 1 quart (0.95 L) per 5 gallons (19 L) of beer, but this varies with the style of beer. To reduce the risk of contamination during storage, it is a good idea to can the wort.

See PARTI-GYLE BREWING.

The common name for calcium sulfate (CaSO4). When added to a mash with a high pH, it becomes a source of calcium, which will help lower the pH. One gram of calcium sulfate added to water will add 62 ppm calcium ions and 148 ppm sulfate ions.