One of Munich’s top brewers, now owned by Paulaner. The company was founded in 1417.

Producer of Munchner Hell, Hacker-Bräu Edelhell, Munchner Dunkel, Pschorr-Bräu Weisse, and Hubertus Bock, among others.

In Britain, a blend of two styles of beer — for instance, bitter and porter, bitter and stout, or bitter and mild ale. It is analogous to a Black and Tan.

See BLACK AND TAN.

See MASS. BAY BREWING CO.

Hart Brewing Inc. was founded as the Hart Brewing Co. in 1984, one of the first generation of northwestern microbreweries. The company was started by Beth Hartwell and her husband, Tom Baune, in a turn-of-the-century general store in Kalama. They later sold the company to a group of five beer enthusiasts, and it has expanded rapidly in the years since.

One thing that has stayed the same is the Baune-Hartwell Pyramid trademark, chosen because of the ancient Egyptians’ role in the development of beer and brewing. The Pyramid logo, which appears on the Pyramid labels, represents great pyramids rising from the coniferous forest of the Northwest, an apt symbol of the impact new small brewers have had on the beer market in the region. The Pyramid product line includes Pyramid Best Brown, Pale Ale, Wheaten Ale, Hefeweizen, Amber Wheat, Snow Cap, Wheaten Bock, Porter, and Kälsch.

Daily tours of Hart Brewing Inc.’s new facilities in downtown Seattle are offered to the public.

Hart Brewing Inc. produces both Pyramid Ales and Thomas Kemper Lagers.

Hart now owns another small northwestern brewer, Thomas Kemper Brewing Co. of Poulsbo, Washington. Hart acquired Kemper in 1992 and expanded the operation substantially. Kemper is a lager craft brewery, with products that include WeizenBerry, Rolling Bay Bock, Winterbräu, Pale Lager, Amber Lager, Dark Lager, Oktoberfest, Hefeweizen, and White (a Belgian-style wheat beer).

Pyramid Apricot Ale

A light-bodied ale with a powerful apricot aroma. There is fruit in the flavor as well, and drinking this beer might be likened to consuming an intoxicatingly fruity potable perfume. Though not a session beer, Pyramid Apricot ale is delicious for dessert.

Hart continues to brew the Pyramid and Hart brands in Kalama, and Thomas Kemper remains a distinct brewery. The company has built a brand-new brewery in Seattle near the Kingdome. This brewery will make beers from both product lines.

Hart has been especially bold in introducing new specialty beers, including Espresso Stout and Pyramid Apricot Ale. Both brands, in their style and substance, appeal to people who might not ordinarily drink beer. While the Apricot Ale is made with the natural essence of apricots, the Espresso Stout gets its rich flavor not from coffee beans but from dark specialty malts.

Espresso Stout

A clean, strong brew brimming with a rich, nutty flavor. Smooth but powerful, it has chocolate and fruit notes. With the gourmet coffee boom in full swing, the tie-in with stout is a natural.

Pyramid Ales’ new Kälsch, a refreshing golden ale inspired by the local “Kölsch” beers of Cologne, Germany, arrives in bottles and barrels just in time for summer.

See MARKET SHARE, MICROBREWERY, and STOUT.

Perhaps the only individual who can claim responsibility for a beer style, Entire. Harwood operated the Blue Last Brewery in London. His clientele were cobblers, who were fond of a beer cocktail drawn from three casks. Tiring of hand-mixing three varieties of beer into one portion, Harwood ordered this mixture, called Entire or Entire Butts, to be brewed locally.

The Entire style was the precursor to porter. It relied on an odd collection of ingredients, including a particular kind of bean and stale or soured ale. Dark porter was the precursor of stout, and Harwood’s brainchild soon spawned the porterhouse, where London porter and a cheap cut of meat, called a porterhouse steak, were the bill of fare.

See PORTER.

An Egyptian goddess of beer, queen of dance, and queen of drunkenness. Usually depicted as a voluptuous woman with the head of a cow, Hathor appears with a human face in most references.

When Ra, the sun god, lost his patience with the human race, he decided to punish the people by turning Hathor loose. She did her job well, as the streets were flooded with blood, and the survival of the species was very much in doubt. Once started on her gruesome work, Hathor was not easily stopped. To slow her down, Ra took the human blood flooding the towns and added barley and fruit. The resulting mixture became the world’s first beer. The next morning, when the goddess returned to finish her job, she was stopped cold by an ocean of beer. Tasting the beer and liking it, she quickly became drunk, forgot about finishing off humankind, and went on her merry way. Since then, Hathor has remained the chief Egyptian goddess of beer and drunkenness.

A condition in which beer appears to be cloudy. Brewers refer to two types of haze, temporary haze (usually called chill haze) and permanent haze. Both types of haze are caused by proteins bonding with tannins, but the bond formed in a chill haze is weaker than that formed in a permanent haze. A chill haze forms at temperatures near freezing but disappears when the beer warms to near 50°F (10°C).

Haze problems can be reduced by careful mashing, sparging, and boiling; by filtering the beer to remove protein particles; or by using proteolytic enzymes, gelatin, isinglass, or other additives.

See CHILL HAZE.

See HOMEBREW BITTERING UNIT (HBU).

The foam at the top of a glass of beer, present after decanting. The term can also refer to the froth that forms on top of the wort during the primary fermentation. Head retention is often a characteristic used to rate or judge a particular beer sample and is measured by the time required for a 3-cm (0.39 inch) foam collar to disappear from the top of a decanted beer sample.

A piece of equipment, generally of stainless steel plate and frame construction, that is used in wort cooling, cold filtration, and hot liquor heating. All types of heat exchangers depend on the counterflow across plates (occasionally tubes) of different-temperature liquids. For example, chilled water or naturally cold city water is used in wort cooling, with maybe a second glycol pass for low-temperature fermentation. In cold filtration, propylene glycol or brine at 26°F (-3°C) or lower is used to chill beer. In hot liquor heating, steam might be used in the exchange process.

See CHILLING, GLYCOL CHILLER, and GLYCOL JACKETS.

A brewing method that calls for using less water than usual at the beginning of the process, then adding the remaining water later. Heavy brewing, an invention of the United States brewing industry, is based on the fact that a particular amount of grist and water will produce a particular wort, which when fermented will produce a particular beer. Typically, a wort with a density of 11 degrees Plato will produce a beer of about 4.8 percent alcohol by volume, to which hops are added to a bitterness level of 15 IBU. This will occupy a particular volume in brewing, fermenting, and aging vessels. In heavy brewing, a brew of 11 degrees Plato is made by using, say, 70 percent of the water used normally, resulting in a beer with an original gravity of 15.7 degrees Plato, 6.9 percent alcohol by volume, 21.4 IBU, and a dark color. The remaining water is then added (carbonated), at the end of the process, to produce the final product. In this way, the brewery can increase its capacity by 30 percent — the same number of vessels hold 30 percent more wort. Most authorities agree that there is no difference in the quality of a heavy-brewed beer compared to a beer produced by the standard method.

A unit of measurement equivalent to 100 liters. Hectoliters are the standard metric unit of measurement for beer.

G. Heileman, once an obscure regional brewery, rose to prominence in the 1980s when its regional brewery acquisitions made it one of the largest United States brewers. The company operates several well-known regional breweries, including Blitz-Weinhard Brewing Co. of Portland, Oregon (brewers of Henry Weinhard’s Private Reserve); Rainier Brewing Co. of Seattle, Washington (Rainier Ale); The Lone Star Brewing Co. of San Antonio, Texas (Lone Star); Carling National in Baltimore, Maryland (National Bohemian); and the Old Style Brewery in La Crosse, Wisconsin (Old Style).

Purchased by Australian financier Alan Bond in the mid-1980s in a leveraged buyout, G. Heileman could not overcome a debt burden that plunged it into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1991. It remains the fifth-largest United States brewing company, but declining sales have forced a substantially downsizing. After the company hit the skids, several breweries broke off to do business on their own, including Pittsburgh Brewing Co. of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Evansville Brewing Co. of Evansville, Indiana; and Minnesota Brewing Co. of St. Paul, Minnesota.

Called the world’s largest six-pack, the tanks at the G. Heileman Brewing Co., Inc., in La Crosse, Wisconsin, hold 22,200 barrels of beer — enough to fill 7,340,796 cans.

In early 1994, the Hicks, Muse investment group purchased G. Heileman and installed new management. Hicks, Muse has had a good track record in turning damaged companies around.

Most of the company’s beers are available in the regions surrounding each brewery. G. Heileman does not have a national brand, one reason, according to analysts, that the company has had difficulty building market share.

See REGIONAL BREWERY.

Fittingly, Heineken, one of the world’s truly international brewers, originated in Amsterdam, one of the world’s great shipping ports. The brewery got its name from Gerard Adriaan Heineken, who acquired the De Hooiberg brewery in 1864. De Hooiberg was a small brewery that had been founded in 1592 and was serving a small regional market. Soon after the Heineken takeover, the market expanded to the entire country and abroad.

Heineken produces its beers at more than 90 breweries in some 50 countries around the world. Heineken beers are exported to another 60 countries. The company has brewery interests, licensing agreements, and export deals on every continent. In Europe, Heineken has breweries in the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Ireland, Hungary, and Switzerland. The combine’s primary international brands are Heineken, Amstel, Buckler, and Murphy’s Irish Stout.

Henry Weinhard’s Private Reserve

Henry Weinhard, a German immigrant, was the founder of the Henry Weinhard Brewery in Portland, Oregon, in the mid-19th century. Following Prohibition, the company merged with a competitor to form Blitz-Weinhard. This new company introduced Henry Weinhard’s Private Reserve in the late 1970s, before the brewery was acquired by G. Heileman. By the early 1980s, this product had developed something approaching a cult following in certain markets. Weinhard’s, with a dash more hop character than the archetypal American lager, is only marginally more characterful than its mainstream competition; the enthusiastic reception it was accorded is an indication of just how thirsty people are for beer with character. G. Heileman has big plans for Weinhard’s and hopes to build it into a quasi-national brand.

Heineken Special Dark

A rich, roasty brew that starts with a velvety maltiness that carries through to a sweet aftertaste. It has a strong malt aroma with a kiss of hop character.

Heineken exports its beer to the United States. Although the company has operated a brewery in Canada, it has never brewed in the United States, believing that the beer’s import status provides it with cachet. The Heineken brand is currently the best-selling import in the United States.

Heineken’s United States franchise got its start when an enterprising Holland America cruise line steward began importing the beer after the repeal of Prohibition. This canny steward, named Leo Van Munching, Sr., soon built a profitable trade selling Heineken in New York and farther afield. His son, Leo Van Munching, Jr., built the business into the most powerful beer-importing franchise in the country. The company was recently bought by its Dutch parent and is now known as Heineken, U.S.A.

See STOUT.

The pharaonic Egyptian term for beer. Also called hequ.

See EGYPTIAN BEER.

See FRUIT, VEGETABLE, HERBAL, AND SPECIALTY BEERS.

A wide range of herbs and spices, from cinnamon to Szechuan peppers, are added to beer. Most recipes use only whole spices or fresh herbs. There are several ways to use herbs and spices in brewing. The spices may be added to the boiling wort; they may be added at the end of a boil, just as finishing hops are; a tea may be made by steeping the herbs and spices in water before adding them to the wort; or a spice extract may be made by soaking the spices in vodka or another alcohol to extract as much of their essence as possible. In the last case, the alcohol acts as a solvent.

One of the most common uses of spices is in fest beer — beer specially brewed for the winter holidays. A mixture of spices normally used in traditional Christmas baking — such as cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, and cloves — is often used. A commercial example of this type of beer is Anchor’s Our Special Ale.

|

||||

| Spices Used in Beers | ||||

| Spice | Amount per 5 Gallons (19 L) | |||

| Anise | ½ to 1 teaspoon (2.5 to 5 ml) | |||

| Cardamom | ½ to 1 teaspoon (2.5 to 5 ml) | |||

| Cinnamon | 1 stick for light flavor, 3 to 4 sticks for sharper flavor | |||

| Cloves | 2 cloves for light flavor, 5 or more for sharper flavor | |||

| Coriander | ½ to ¾ ounce (14 to 21 g), pulverized | |||

| Fennel | ½ to 1 teaspoon (2.5 to 5 ml) | |||

| Ginger | 2 to 6 ounces (57 to 170 g), shredded | |||

| Nutmeg | ½ to 1 teaspoon (2.5 to 5 ml) | |||

|

||||

Flowers also are used for flavoring. For example, lavender, heather, and rose petals have been used in beers. Mint has been used in some beers, with good success in meads. Similarly, spruce, juniper berries, and other unusual ingredients have been used to flavor beers.

Some spiced or herb-flavored beers are brewed fairly often. Quite a few homebrewers have experimented with ginger beers, and some commercial beers are brewed with chili peppers — for example, Ed’s Original Cave Creek Chili Beer — although these are often viewed as curiosity items. Different varieties of chili peppers will produce sharply different flavors and levels of heat. The heat of a pepper is produced by a chemical called capsaicin. Most brewers would not want anything hotter than a jalapeño. Most chili pepper beers are based on a light pale ale or a light lager. The pepper can be added at various stages, either in the boil, the primary ferment, the secondary ferment, or the bottling.

See FRUIT, VEGETABLE, HERBAL, AND SPECIALTY BEERS.

A spasmodic inhalation, with closure of the glottis, accompanied by a peculiar sound. Believed by some to derive from the hekt (beer) cup of the ancient Egyptians. A commonly observed sign of overindulgence.

Beer brewing is an art first developed in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) more than 8,000 years ago. Residual materials found in ceramic pottery identified by archeologists as the remnants of the beer makers’ craft give us reason to believe beer’s origins go back 10,000 years. But without written or archeological evidence, a birth date for beer beyond 8,000 years ago must remain speculative.

Evidence of brewing activity from 5,000 years ago is in the form of clay tablets with cuneiform (wedge-shaped) inscriptions that were discovered around 1840 at Nineveh and Nimrud by Austen Henry Layard, an Englishman who chanced upon Assyrian ruins while journeying overland to Ceylon. He had hoped to find some sort of inscriptions in stone, but what he discovered was a buried library of over 25,000 broken tablets which he removed to the British Museum for translation. The translations were begun by Henry Rawlinson, a British officer who had discovered the key to deciphering cuneiform — the “Record of Darius” — on the Behistun rock near the city of Kermanshah in Iran.

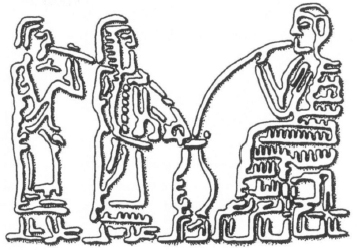

A bakery and brewery from the tomb at Meket-Re at Thebes, Egyptian Dynasty XI, ca. 2000 B.C.

Pictograms such as this of Norman conquerors enjoying beer help us to determine just how old beer is.

Many of the cuneiform tablets were commercial ledgers, which show us how beer, or kash, was used as currency or an instrument of barter. Records describe how the stonemasons who built the great structures of the pharaohs were paid with vessels of beer. Beer was used as a dietary staple before bread-baking was discovered.

According to Shin T. Kang, translator of cuneiform tablets:

“Together with bread, onions, fish, and seed-seasoning, beer was one of the more important items in the ancient Mesopotamian diet. The Sumerians seemed to have made a fermented beer by combining barley and water, and adding flavorings such as malt. Beer was used as part of the rations of government officials, and messengers, and was widely expended in offerings to gods and goddesses, such as for the goddess Angina, at the field-offering for deceased persons, and much was consumed at the palace. For all these purposes, beer was collected from the people, either as a form of taxation or as a religious gift.”

From the following translations of cuneiform tablets by Mr. Kang, one can see that beer was an important commodity.

1 ordinary beer, royal (quality) —inspected by the constable of the king: for the sheep-shearing.

Receipted by the governor.

The year when the city Simurum was destroyed for the 9th time.

550 sila of fine beer

31 gu, 190 sila of ordinary beer for the meal offering: from Lú

Receipted by Ur-sa

The month of the goddess Lisin

The year when the city of Sassurum was destroyed.

18 sira of fine beer,

70 ordinary beer,

60 weaker beer, 15 sila,

for the offering of prayer to the goddess Inanna at Uruk,

on the 28th day.

From Ur-mes.

Receipted by the governor.

Hieroglyphics such as this one suggest that beer drinking was a part of early Egyptian life.

The month of the divider.

Year that in which the city Simanum was destroyed.

15 sila of fine beer,

55 sila of ordinary beer,

on the 16th day;

15 sila of fine beer,

50 sila of ordinary beer,

on the 17th day;

10 sila of fine beer,

40 sila of ordinary beer,

on the 18th day;

40 sila of beer,

on the 19th day;

15 sila of fine beer, 40 sila of ordinary beer for queens and priestesses.

From A’alli.

Receipted by the governor.

The month of the 6-month temple.

Translations also reveal laws and religious prayers and hymns that refer to beer or its ingredients.

“The waitress, who gives free beer or barley, can not ask for anything in return.”

“When certain criminals and political dissidents gather at the tavern, and the waitress will not turn them over to the Palace (authorities) — she will be killed.”

Life was tough for nuns, too:

“Should a nun open a beer-house, or even so much as step into a tavern (beer bar) for a beer — this citizen will be burned.”

The allure of beer must have been strong, even for the religious. Here is a prayer to (or about) Ninkasa, the great goddess:

Ninkasa, the smart gem of her mother,

Her mash tun is of greenish Lapis lazuli,

Her beer stein is made of hammered silver and gold.

Her presence by the beer makes it seem magnificent,

She brings joy when she sits by the beer.

With a special mug she pours the beer, and goes about untiring, having the mug tied around her waist.

May the wine I serve be especially good.

The bird who drank the beer is sitting here and is happy,

He is supposed to help me find the troops of Uruk.

Another prayer:

The gods cried over the land.

She was not hungry because of her distress, but was thirsty (longing) for a beer.

In 1933, the ancient city of Mari, on the Middle Euphrates in eastern Syria, was excavated by French archaeologists. Some 13,000 tablets were discovered, as well as the ruins of a palace. Mari was pillaged by Hammurabi of Babylon around 1760 B.C. The important point is that the tablets shed light not only on international relations, but also on the public and the private lives of the inhabitants.

The people at court lived and ate well. The tablets reveal that the people ate beef, mutton, wild game, and fish, as well as vegetables such as peas, beans, and cucumbers. Garlic was available. Dates, figs and grapes were commonly mentioned in the tablets, along with herbs and spices. According to the tablets, bread was made in several forms. One was thin crisp disks made from barley flour (for baking bread, wheat flour is vastly superior to barley flour). There was also leavened bread. So, the basic ingredients for making beer were at hand — barley, and yeast in leavened bread. Indeed, beer was locally produced, but wines had to be imported from other countries.

In Babylon, under Nebuchadnezzar, beer was the main drink. It was brewed in many different styles that determined which herbs and spices were used to flavor it.

So, before we had the Great Pyramids, and the Sphinx, and Cleopatra’s needles, before the mighty Greek and Roman empires, there was beer.

Sadly, brewing and the brewing culture in Mesopotamia were destroyed by the Mohammedan conquests of the Middle East in the 8th century A.D. The Koran, the holy book of the people, forbids the consumption of alcohol. (Some secular Middle Eastern states do, now, brew beer: Iraq, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. Most of the breweries are state owned.)

Phoenicia was the ancient Greek name for the long and narrow coastal strip of Palestine-Syria extending from Mount Carmel north to the Eleutherus River in Syria. Phoenicia developed into a manufacturing and trading center early in the history of the Near East. By the second millennium B.C., a number of Phoenician and Syrian cities, including Arvad, Berytus, Byblos, Sidon, Tyre and Ugarit, achieved preeminence as seaports. They vigorously traded in purple dyes and dyestuffs, glass, grain, cedar wood, wine, weapons, and metal and ivory artifacts. Since the beer culture passed from Mesopotamia into Egypt, it is conceivable that Phoenician ships made beer runs along the North African coasts.

Early in the first millennium B.C., Phoenicians explored the Mediterranean as far as Spain and into the Atlantic, establishing colonies on the Tunisian coast at Carthage (ca. 800 B.C.), beyond the Strait of Gibraltar at Cadiz, and elsewhere along the Atlantic coast. Phoenician enterprise turned the Mediterranean, from the Levant to Gibraltar, into a great maritime trading arena. The Phoenicians were merchants and sailors. They only participated in domestic homebrewing and therefore their contribution to the beer culture was localized.

See HECTOLITER.

The village of Hoegaarden has a history of brewing dating back to 1318. Monks settled in the area in 1445, and by 1770 were producing more than 25,000 hl of beer each year. By 1880, this village of 2,000 had 35 breweries.

The major product of the Hoegaarden breweries was a white (wheat) beer, but this style declined in popularity during the post–World War II era, and the last brewery closed in 1957. The tradition was revived by a milkman named Pierre Celis, who had worked in one of the local breweries as a youth. Celis’s Hoegaarden Brewery single-handedly resuscitated the white beer style. Interbrew, S.A., brewer of Artois, one of Belgium’s major brewers, eventually bought him out. After selling Hoegaarden, Celis emigrated to Austin, Texas, where he started a successful microbrewery.

The flagship white beer is made from a mix of malted barley and wheat. Hops, coriander, and curaçao are then added to the boil. The wort is cooled, and fermentation begins in large (1,400 hl) fermenters. At a certain point, small amounts of sugar and yeast are added to the beer. Once it is bottled or kegged, it is kept in warm storage to allow a secondary fermentation to take place.

Today Hoegaarden’s white beer is popular throughout Europe, where it is highly regarded for its healthful properties. The brewery produces more than 800,000 hl per year. Hoegaarden white beer is imported into the United States by Paulaner North America of Englewood, Colorado.

See CELIS BREWING CO. and WHEAT BEER.

See BELGIAN WHITE BEER.

Founded in 1589 as the Bavarian court brewery of Wilhelm V, Hofbräu moved to its current location in 1828. As Germany’s political institutions evolved, Hofbräu passed from royal hands to those of the state government. To this day, the company is operated by the government of Bavaria.

The brewery produces beer for its world-renowned beer hall, the Hofbräuhaus. The Hofbräuhaus was renovated in the late 19th century, became a favorite of the Nazi party during its rise to power (Adolf Hitler delivered speeches there on occasion), and today is the premier international gasthaus in Munich. On any given day, the Hofbräuhaus is mobbed with tourists. It can accommodate 2,500 people within its cavernous halls. An outdoor beer garden offers a somewhat less raucous environment in which to sample Hofbräu’s beers, which are uniformly excellent.

The brewery is said to be one of the originators of the bock beer style, and its Maibock and Delicator doppelbock are not to be missed. Hofbräu produces numerous brands, including Altmunchner Hellgold, Altmunchner Dunkelgold, Munchner Kindl Weissbier, Pils, Urbräu Hell, Weizen Hefefrei, Delicator, Maibock, Octoberfestbier, Octberfest Märzen, and Festbier.

In the past, the company’s beers have been imported by Hudepohl-Schoenling of Cincinnati, Ohio, a regional brewery and sometime beer importer with German roots.

See BOCK BEER and OKTOBERFEST BEER.

Holsten is an aggressively international German brewer, producing beer at seven German breweries and eight foreign plants. The company proudly states that foreign markets account for 40 percent of its sales, and Holsten Premium is now sold in more than 40 countries. In the United States, Holsten brands are imported by Holsten USA in Tarrytown, New York.

Holsten Diat Pils

In 1952, Holsten developed an extended fermentation process intended to convert a greater amount of the wort sugar to alcohol. The beer that was created using this process was originally aimed at diabetics but became Great Britain’s most popular German import. Holsten Diat Pils was introduced in the United States in 1989 as Holsten Dry. It is a crisp, highly attenuated beer with an assertive hop character.

A formula devised by Charlie Papazian to estimate the bitterness of hopped malt extract. It is also called the alpha acid unit (AAU). The HBU is determined by multiplying the equivalent number of ounces of hops by the alpha acid percentage of the hops used. For example, 2 ounces of 5 percent alpha acid hops in a 3.3-pound can of hopped malt extract would yield 10 HBU.

See ALPHA ACID UNIT and INTERNATIONAL BITTERNESS UNIT (IBU).

The craft of brewing beer at home rather than in a brewery setting. Homebrewers in the United States look to the American Homebrewers Association (AHA) as their primary support organization. In many cities and towns across the United States there are homebrewing clubs that provide technical support, recipe sharing and troubleshooting information to homebrewers.

Basic homebrewing equipment

Homebrewers are often so involved in their craft that they design and print their own labels.

See AMERICAN HOMEBREWERS ASSOCIATION and ASSOCIATION OF BREWERS.

Honey is most often used in making meads, although commercial craft brewers also use it to make interesting variations of standard styles.

The type of honey used will affect the flavor of the beer or mead. Light honey flavors are provided by sage flower, orange blossom, clover, alfalfa, and mixed honeys. Stronger flavors are provided by buckwheat and heather honeys.

When used in brewing, honey should be pasteurized, because it contains yeast and bacteria. Many homebrewers and mead makers prefer to boil their honey, but doing so may drive off volatile aromatic compounds.

To pasteurize the honey while preserving its delicate flavor, it may be heated in a pressure cooker to 176°F (80°C) for 2½ hours. The honey is then added to the beer in the primary ferment when the yeast reaches high kraeusen (a large head of foam). The amount of honey added will depend on the type of honey and the intensity of flavor desired. Subtle honey flavors are achieved with 1 pound (0.45 kg) or less per 5-gallon (19 L) batch, noticeable honey notes with about 2 pounds (0.9 kg), and very pronounced honey characteristics with more than 3 pounds (1.35 kg). When honey constitutes a significant percentage of the fermentables in a malt-based beer, it is often referred to as a bragget. The character of meads is dominated by honey, which constitutes up to 100 percent of the fermentables (some variations include significant fermentables from apple cider, grape juice, and other fruits). Honey is approximately 25 to 35 percent water, leaving 65 to 75 percent fermentable sugars — and that is 100 percent fermentable sugar, which is why meads often have a final gravity of less than 1.000 (alcohol is lighter than water). The sugars in honey are primarily the simple sugars (monosaccharides) fructose and glucose, although trace amounts of maltose and sucrose are present.

A stainless steel vessel into which wort from the brew kettle is cast in a brewery using whole hops in the boil. The vessel has a removable slotted or drilled base that acts as a strainer. The kettle is cast, and the hops are allowed to settle over the strainer. Normally, a cone-shaped bottom is used in a hop back, which enables the hops to build a deep, packed base. This further aids filtration of the wort, as precipitated proteins remain on top of the hops during runoff to the fermenting vessel.

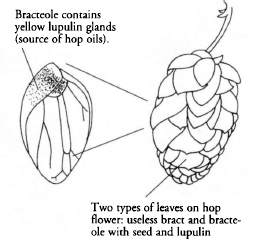

Hop flower

Fresh whole hops can be added into the hop back prior to casting the brew kettle to help impart some hop fragrance. When running off from a hop back, the first few gallons are normally recirculated until bright wort is achieved.

A twisting, leafy stem of the hop plant. The leaves and hop cones sprout from the bine. Each plant has several bines.

Hop bines are trained along strings either up a central pole or to overhead wires to which the strings are attached. They may grow to more than 20 feet, although some new varieties of hops grow to a more manageable length of 8 to 10 feet. The new varieties produce the same yield as their much taller relatives.

Trained hop bines

The vining plant Humulus lupulus, a member of the Cannabinaceae Family. This is a native perennial plant found in the temperate zones of Europe, North America, and Asia and is used almost exclusively for brewing purposes. Hops are believed to have many medicinal properties, such as aiding sleep, stimulating appetite, and aiding digestion. Hops also are used as a preservative. A related annual species, Humulus japonicus, grows in Japan and is used mainly as a quick-growing garden screen.

The common hop originated in Europe and is a long-lived perennial with rough, climbing stems that wind clockwise around a support or trellis. The plant can grow up to 25 feet (7.5 m) in a single season. Under favorable conditions, hops have been recorded growing 6 inches (23 cm) in a single day. The stem produces strong, hooked hairs that help the plant cling to its support. The leaves are dark green, hairy, and heart-shaped. They are serrated and deeply lobed, with three to five lobes each.

Hops are dioecious — that is, they have separate male and female plants. Identification of the sex of the plant is possible only when the plant blooms. The male flowers form pyramid-shaped, loosely branched flower clusters that are 2 to 6 inches (5 to 23 cm) long. The male plant is usually not used except in breeding new hop strains or in improving crop yields. Wind carries the pollen to the female flowers — short spikes or catkins that hang in clusters. During their development, the stem elongates and the petals, or bracts, expand, forming the scales of the mature cones, or strobiles. The mature strobiles are yellowish green and oblong or ovoid in shape. They can be up to 4 inches long and feel papery. The mature, dried strobiles constitute the commercial hop.

The grooming of hop plants is the subject of this illustration.

Weighing hops at the Samuel Smith Brewery in Yorkshire, England

The female hop plant is the one used in brewing.

The hop flower

Located at the inside base of the bracts are many tiny yellowish glandular sacs called lupulin glands. These sacs contain resins and essential oils, along with nitrogen, sugars, pectin lipids, and wax. They can make up as much as 15 percent of the flower’s weight. The resins and essential oils contained in the lupulin glands provide the distinct bitterness, flavor, and aroma in beer, as well as its reputed medicinal attributes.

Hops grow well over a wide range of climatic and soil conditions but thrive best in deep, well-drained soil. Soil that is shallow, contains an abundance of clay, or does not drain well should be avoided. Hops require plenty of water during spring and summer but none in autumn. They need direct sunlight and should not be grown in regions that are subject to long, severe winters. They prefer warm, windless summers and should be harvested before the first frost. In autumn, winter, and early spring, the soil should be prepared for the upcoming season by weeding and adding manure before the shoots appear.

The bracteole leaves of the female plant are the source of hop oils.

Propagation is done by taking root cuttings in the winter after the plant has withered and gone dormant. This is done by uncovering the root of the plant and locating a large shoot with numerous buds, also known as a rhizome. The rhizome is cut off and planted sometime before the spring growing season. This method ensures the continuation of a particular strain, as each new plant will be genetically identical to its parent.

At a typical commercial farm in the United States, hops are planted in rows of hills spaced 6 to 8 feet (2 to 2.5 m) apart, with the rows 7 to 8 feet (2 to 2.5 m) apart, yielding 680 to 1,000+ hills per acre. In England, hops are planted 3 to 7½ feet (1 to 2 m) apart, with the rows 6 to 9 feet (2 to 3 m) apart, depending on the trellis system used, yielding 774 to 2,420 hills per acre.

Growing methods vary from country to country, but in all cases some support for the vines must be provided. Generally in the United States and England, the vines are trained to climb strings suspended from wire trellises and attached to a stake at each hill. In other countries, the vines climb poles located at the hills. In the United States, two strings are used per hill, whereas in England two or four strings are used. As a rule, two vines usually share a string. The height of the trellises ranges from 8 to 25 feet (2.5 to 8 m) depending on the country. In the United States, almost all trellises are 16 to 18 feet (5 to 5.5 m) high to facilitate the use of harvesting machines.

Hops are heavy feeders, needing a lot of calcium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These are added in either organic or inorganic form. In the United States, the common source is farmyard manure or green manure, onto which a cover crop of a nitrogen-fixing plant is sown in the fall and plowed under in the spring. In England, large amounts of manure, fishmeal, and other materials are added in the fall and plowed under in the spring.

When the hops are ripe, they become bright yellowish green, sticky, crisp, and papery. At this time, they contain the maximum number of lupulin glands. Overripe cones turn a darker yellow, shatter easily, and have lost some lupulin glands. For the most part, hops mature fairly consistently from year to year, depending on the variety and the environmental conditions. When harvesttime arrives, hops are picked by hand or by machine. In the United States, they are picked almost entirely by machine. In England, they are picked by both methods. Some people consider handpicking to be the superior method, as fewer lupulin glands are lost during the harvest.

Dried hops are aged in bins for 1 to 12 days.

The typical procedure in the United States is to cut the vines and take them to a mechanical harvester housed in a shed. A typical large-scale picker, or harvester, has wire picking fingers or loops mounted on bars that travel over the vines, plucking the cones as they pass. Portable machines and other picking designs are also used.

Once the hops are picked, they are gathered and taken to a hop kiln, or oasthouse, as it is called in England. There they are loosely and evenly scattered on a slatted floor covered with burlap or wire mesh. The bed of hops may be up to 40 inches in depth. Hot air is then allowed to pass through the hops by natural convection or by forced air for deeper beds. Fresh hops have a moisture content of around 80 percent, which is reduced to about 8 percent by drying. Temperatures are usually 140° to 150°F (60° to 65.5°C) for bittering hops and 130°F (54°C) or less for aromatic hops. The drying time ranges from 6 to 20 hours depending on the depth of the hop bed, humidity, air temperature and velocity, and original moisture content of the hops.

Hops are being harvested in this illustration from Twenty-five Years of Brewing, published in 1891.

The dried hops are moved to bins, where they will cure for 1 to 12 days, depending on the capacity of the bins. Curing allows the moisture left in the hops to equalize. It also improves the aroma and makes the hops more pliable to withstand the baling process.

The cured hops are then compressed into bales. In the United States, a hop bale is approximately 18 cubic feet (0.5 cubic meters) and weighs around 200 pounds (90 kg). The hop bale is then wrapped in plastic or burlap. Some growers vacuum seal the bales under nitrogen or carbon dioxide in an oxygen barrier-type material such as a foil-Mylar laminate. In England, bales are compressed into “pockets” that weigh about 160 pounds (72 kg).

Most hop bales are sold to a hop broker. The broker inspects the hops and accepts or rejects them based on their quality. After they are accepted, they are analyzed for alpha acid content and many other characteristics, then placed in storage in a refrigerated warehouse. Without direct sunlight and under low temperature (around 32°F, or 0°C) and low moisture conditions, they suffer little oxidation and will keep for up to 2 years.

Typically, a buyer from a brewery will purchase a year’s supply of hops. The brewery will then take shipments from the broker who is storing the hops on-site. The broker will take samples and test the alpha acids throughout the storage stage.

Whole hops are also called leaf hops or whole-leaf hops. These terms are somewhat misleading because the flower, not the leaf, is used for brewing. Whole hops are the hops taken directly from the bales and repackaged into smaller containers. These hops will expand to near their original size and look the same as before baling, though a bit flattened, and most of the lupulin glands will be intact. Poor storage and packaging materials may cause whole hops to lose their alpha acids and essential oils faster than other forms of processed hops. With today’s oxygen barrier packaging and cold storage, however, their quality is usually ensured.

Three of the four kinds of hops used in brewing are pellets (top left), plugs (bottom), and whole flowers (upper right). The fourth form is hop extracts or oils.

Hop plugs are whole hops that have been compressed into approximately .5-ounce (14 g) plugs that measure 1 inch (2.5 cm) across and are 5 inch (1.3 cm) thick. These are also known as Type 100 pellets. They take up one-third the space of whole hops.

Hop pellets are made by running the hop bale through a hammer mill to reduce them to a fine powder. The powder is then compressed and extruded through a pellet die to make a final product that looks much like rabbit food. Great care is taken to generate as little heat as possible to prevent the loss of too much of the hop resin. Typically, the pellets are vacuum sealed in foil bags weighing 44 pounds (20 kg). Hop pellets take up about one-quarter the space of whole hops. They are also known as Type 90 pellets.

Hop extracts and oils fall into one of three main categories: iso-alpha extracts, hop oil extracts, and total extracts containing all the hop elements. Iso-alpha extracts add bitterness to beer but do not add flavor or aroma. Hop oils add aroma but no bitterness. Total extracts provide bitterness, flavor, and aroma. The process used to make these extracts varies, but solvent extraction is the most common method for making iso-alpha extracts and total extracts. Steam distillation is used to make hop oil extracts directly from whole hops or from a total extract.

The amount of essential oils in hops is about 0.5 to 2 percent of the total weight. It is rare to find the oil content listed on a package of hops, but some suppliers have started listing it. The oil is very volatile and is lost quickly during storage and in the boiling of beer. Thus, aromatic hops are added late in the boil or at the end. They also may be added after the first stage of fermentation, which is called dry hopping. Less than 2 ppm of hop oil is normally used. Typically, 1 to 4 ounces (28 to 113.5 g) of whole hops or pellets are used in a 5-gallon (19 L) batch of homebrew. The amount and variety of hops used depend on the style of beer being made.

Hop oil contains more than 200 different compounds, and it has been extremely difficult, if not impossible, to identify all the compounds that provide the aroma and flavor in beer. Humulene, myrcene, and caryophyllene make up 80 to 90 percent of all hop oils. However, they do not provide all the aroma and flavor. Research has shown that a combination of the three major compounds along with some of the many minor compounds accounts for a beer’s aroma and flavor.

The amount of the three major compounds is used as a metering device in the breeding of new hop strains. Most aromatic hops have a higher percentage of humulene than of myrcene and caryophyllene. Only new hop strains containing higher concentrations of humulene will be tested as potential aromatic strains. This greatly reduces the number of test brews needed and significantly reduces the amount of time required to develop a new strain.

Native Americans in western Washington State picking hops in the 1880s. American hops were in great demand then because of the hop blight in Europe.

Hops also are measured for the amount of alpha acid they contain. This is expressed as a percentage, found by dividing alpha acid weight by the total hop weight. This percentage is important to brewers because they are trying to maintain a consistent product, and the alpha acid content of hops varies from harvest to harvest and may be affected by prolonged or improper storage. By knowing the alpha acid content of the hops, brewers can calculate exactly how much hops to add to their brew.

The exact amount of bitterness of a beer is measured in International Bitterness Units (IBU). One IBU is approximately equal to about 1 mg of iso-alpha acid per 1 L (1.06 quarts). To obtain the exact IBU, a sample of beer is shaken with a solvent of iso-octane, which extracts the iso-alpha acids from the beer. This mixture of solvent and iso-alpha acids is then placed in a spectrophotometer and exposed to ultraviolet light. The spectrophotometer measures the amount of light that is absorbed by the mixture, which is proportional to the amount of iso-alpha acids in the sample. From this data, the IBU number can be calculated.

Keep in mind the following:

1. The average alpha acid content is based on whole hops and will vary from season to season. The average alpha acid content will be lower for hop pellets.

2. Storage is a rating designed to estimate how much alpha acid is lost during a 6-month storage period at 68°F (20°C). Poor indicates 41 percent or more alpha acid lost, Fair 31 to 40 percent, Good 20 to 30 percent, and Very Good less than 20 percent. Hops kept in an airtight container at temperatures below 32°F (0°C) can be stored for up to 2 years.

3. The Origin column is not necessarily where the strain originated but the country or countries of major production.

Unfortunately, a spectrophotometer is too expensive for most microbreweries, brewpubs, and homebrewers. Thus, another method of measuring hops, the alpha acid unit (AAU). This is a measurement of the alpha acids or potential bitterness in 1 ounce of hops. For example, if 1 ounce of hops had an alpha acid content of 6.4 percent, the hops would be said to have 6.4 AAU; ½ ounce of these hops would have 3.2 AAU. The AAU is also known as the homebrew bittering unit (HBU). Both units are identical.

The major drawback of the AAU is that it is a measurement of the amount of hops being added to the beer, not the amount of bitterness in the final product. Only a fraction of the alpha acids in the hops will be used during the beer-making process. If a brewer starts out with 10 AAU of hops in the beer, the best he or she can hope for is 3 AAU of bitterness in the final product. The actual amount of alpha acids extracted depends on many factors, such as boiling time, how vigorous the boil is, the specific gravity of the beer, and the type of yeast used. The AAU is not the best unit of measurement when trying to maintain a consistent product.

Many hop varieties are available to homebrewers. They are generally divided into two categories based on when they are used in the brewing process. Bittering hops are added early, and all their essential oils are driven off during the boiling process, leaving the bitterness behind. Aromatic hops are added at the end of the boil to retain their essential oils, which impart flavor and aroma but little or no bitterness. A few varieties can be used for either bittering or aroma. See the table on the previous page for a comparison of hops by variety.

A small group of aromatic hops are called noble hops, so named by brewers for their superior ability to impart aroma and flavor. The definitive noble hops are Saaz, Hallertauer Mittelfrüh, Spalt Spalter, and Tettnang Tettnanger. Any other noble hop is measured against these four.

There are as many different beer recipes as there are brewers, and each brewer has a favorite hop to use. Following is a basic hop variety substitution chart. This can be helpful if a particular hop is not available. The substitutes listed are meant only as guidelines. Brewers should feel free to experiment.

When adding bittering hops to beer, it is important to know that not all the alpha acids will be extracted from the hops. It takes a minimum of 10 minutes of boiling to get any bitterness from the hops. This is because the alpha acids must first go through an isomerization process to form iso-alpha acids, which finally provide the bitterness. One would think that since it takes a long time to start extracting the alpha acids, a longer boil will extract more — and maybe all — the alpha acids. The problem is that after a certain length of time, the iso-alpha acids start breaking down and are lost. The breakdown usually starts happening after about 2 hours of boiling. It is for this reason that most brewers boil only for 60 to 90 minutes.

|

||||

| Hop Substitutions | ||||

| Variety | Substitutes | |||

|

||||

| B.C. Goldings | Fuggle, East Kent Goldings, domestic Fuggle, Willamette | |||

| Brewer’s Gold | Northern Brewer, Galena | |||

| Bullion | Northern Brewer, Galena | |||

| Cascade | Nothing equivalent, but it is widely available | |||

| Centennial | Cascade | |||

| Chinook | Galena, Nugget, Cluster | |||

| Cluster | Galena, Chinook | |||

| Crystal | Liberty, Mt. Hood | |||

| East Kent Goldings | Fuggle, B.C. Goldings, domestic Fuggle, Willamette | |||

| Eroica | Galena, Nugget, Chinook, Cluster | |||

| Fuggle (English) | Domestic Fuggle, Styrian Goldings, East Kent Goldings, B.C. Goldings | |||

| Fuggle (domestic) | English Fuggle, Styrian Goldings, East Kent Goldings, B.C. Goldings | |||

| Galena | Cluster, Nugget, Chinook | |||

| Hallertau Hersbrucker | Crystal, Liberty, Mt. Hood | |||

| Hallertau | Domestic Northern Brewer, | |||

| Northern Brewer | Perle | |||

| Hallertauer (domestic) | Crystal, Liberty, Mt. Hood, Hallertau Hersbrucker, Hallertauer Tradition |

|||

| Hallertauer Mittelfrüh | Hallertauer Tradition, Crystal, Liberty, Mt. Hood | |||

| Hallertauer Tradition | Crystal, Liberty, Mt. Hood | |||

| Hersbrucker (domestic) | Crystal, Liberty, Mt. Hood | |||

| Liberty | Crystal, Mt. Hood | |||

| Lubelski or Lublin | Saaz, Spalter Select | |||

| Mt. Hood | Crystal, Liberty | |||

| Northern Brewer (domestic) | Perle, Hallertau Northern Brewer | |||

| Nugget | Galena, Chinook, Cluster | |||

| Perle | Northern Brewer, Cluster, Galena | |||

| Pride of Ringwood | Galena, Cluster | |||

| Saaz | Lubelski | |||

| Saazer (domestic) | Lubelski, Spalt Spalter, Spalter Select | |||

| Spalt Spalter | Spalter Select, Spalter, Saaz, Tettnanger | |||

| Spalter (domestic) | German Spalter, Spalter Select, Saaz, Tettnanger | |||

| Spalter Select | German Spalter, Saaz, Tettnanger | |||

| Styrian Goldings | English Fuggle, any of the Goldings, domestic Fuggle, Willamette | |||

| Super Styrians | Galena, Northern Brewer, Cluster | |||

| Tettnang Tettnanger | Domestic Tettnanger, Spalt Spalter, Spalter Select, Saaz | |||

| Tettnanger (domestic) | Tettnang Tettnanger, German Spalt, Spalter Select, Saaz | |||

| Willamette | East Kent Goldings, Fuggle, Styrian Goldings | |||

| Wye Target | Any bittering hop | |||

|

||||

How much of the alpha acids are retained at the end of the boil depends on how vigorously the wort is boiled, the specific gravity of the wort, the amount of alpha acids introduced, the form of the hops, the boiling time, the wort pH, the type of yeast used in the fermentation process, and quite a few other factors. What all this means is that many factors work against the brewer when he or she tries to calculate exactly how much bittering hops to use to produce a beer with a specific IBU level.

To calculate the amount of alpha acids that will actually make it into any given 5-gallon (19 L) batch of beer, the brewer must know several factors ahead of time. Some of these will not apply in all cases.

1. The concentration of the wort being boiled (CW). If the wort is not diluted after the boil but is a full 5 gallons (19 L), CW = 1. Otherwise, calculate CW.

CW = Final Volume / Boil Volume

2. Use the original gravity (OG) from your recipe and the CW from factor 1 to calculate the gravity factor of the wort (GFW). If OG is 1.050 or less, GFW = 1.

GFW = (((CW × (OG-1))-0.05) / 0.2) + 1

3. Calculate the hopping rate factor (HRF). IBU is the desired IBU of the final beer.

HRF = ((CW × IBU) / 260) + 1

4. Altitude affects the temperature at which the wort will boil. The higher the elevation, the lower the boiling temperature. If you live at sea level or very close to it, AF = 1. Otherwise, calculate AF.

AF=((Elevation in Feet / 550) × 0.02) + 1

Multiply all the factors together to achieve a combined factor (CF).

CF = CW × GFW × HRF × AF

Boiling time of the wort will have an effect on extraction efficiency, or utilization. Locate the length of your boil in the following chart:

| Boil Time | % Utilization |

|

|

| 30 minutes | 11 |

| 45 minutes | 18 |

| 60 minutes | 20 |

| 75 minutes | 22 |

| 90 minutes | 23 |

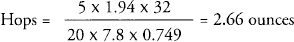

Find the percentage of alpha acid (%AA) on your hop package. Plug in the numbers to calculate the amount of bittering hops you need:

The volume is the volume at the end of the boil, normally 5 gallons (19 L), and IBU is the IBU of the final beer.

Example:

The recipe calls for an original gravity of 1.055. The altitude is 1,000 feet. The desired IBU is 32. A partial boil of 3.5 gallons (13 L) will be done, diluting to 5 gallons (19 L) after a 1-hour boil. The percentage of alpha acid on the hop package is 7.8%.

The amount of hops you’ll need for a 1-hour boil:

Since some of the alpha acids will be lost to the yeast, the answer can be rounded up to 2 ounces.

Remember that the calculation above will give an estimate, and the only way to determine the exact IBU of the final product is to measure it with a spectrophotometer. The estimate is a good starting point, and your taste buds will tell you whether you need to adjust your bittering hops up or down the next time. Keep in mind that hop utilization rates differ by hop form: Rates for whole hops are significantly lower than those for pellet hops.

There are many styles of beer and many varieties of hops. It is important to use the proper hop variety when trying to duplicate a particular beer style because each hop has a different combination of flavor and aroma attributes and intensity. The following chart lists the common hop varieties and their suggested beer styles.

We know beer was brewed over 8,000 years ago, but the earliest indications of hops being used as beer flavoring dates to between the 10th and the 7th centuries B.C. Hops were used in pharaonic Egypt by at least 600 B.C. Evidently, their use in ancient times was not remembered or passed along, or the information did not travel to Europe, because their use there as a bittering agent and as a preservative did not begin until around the 7th or 8th centuries. Some historians place the beginning in the 11th century in the Czech Republic, where it became commonplace. However, references were made in 768 to “humlonaria” — or the name given to hop gardens — given to the Abbey St. Denis by King Pèpin le Bref. There were hop gardens at the Abbey St. Germain des Prés in 800, and at Corvey Abbey sur le Wesser in 822. In 855 and 875, there are references to humularium in the records of the Bishopric of Freising in Upper Bavaria. The presence of hop gardens suggests that hops were used in beer.

|

||||

| Hop Variety vs. Beer Style | ||||

| Variety | Suggested Beer Style(s) | |||

|

||||

| B.C. Goldings | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts | |||

| Brewer’s Gold | English ales, heavier German-style lagers | |||

| Bullion | English ales, heavier German-style lagers | |||

| Cascade | American pale ales, California common, stouts, porters | |||

| American wheat | ||||

| Centennial | American pale ales, American wheat, stouts, porters | |||

| Chinook | Pale ales to lagers, California common, India Pale Ale | |||

| Cluster | Any style | |||

| Crystal | American and German lagers | |||

| East Kent Goldings | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts | |||

| Eroica | Wheat beers | |||

| Fuggle (English) | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts | |||

| Fuggle (domestic) | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts | |||

| Galena | Any style | |||

| Hallertau Hersbrucker | German lagers, ales, wheat beer | |||

| Hallertau Northern Brewer | California common, German lagers | |||

| Hallertauer (domestic) | German lagers, ales | |||

| Hallertauer Tradition | All lagers | |||

| Hersbrucker (domestic) | German lagers, ales | |||

| Liberty | All lagers | |||

| Lubelski or Lublin | Pilsners | |||

| Mt. Hood | American lagers, German lagers, ales | |||

| Northern Brewer (domestic) | California common, German lager | |||

| Nugget | Any style except light lagers | |||

| Perle | American pale ales, porters, German lagers and ales | |||

| Pride of Ringwood | Australian styles | |||

| Saaz | Pilsners | |||

| Saazer (domestic) | Pilsners | |||

| Spalt Spalter | German lagers, altbier | |||

| Spalter (domestic) | German lagers | |||

| Spalter Select | German lagers | |||

| Styrian Goldings | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts | |||

| Super Styrians | Any style | |||

| Tettnang Tettnanger | German lagers, ales, American “premium lagers,” wheat beer | |||

| Tettnanger (domestic) | German lagers, ales, American “premium lagers,” wheat beer | |||

| Willamette | English milds, pale ales, India Pale Ale, porters, stouts, American ales | |||

| Wye Target | English ales and lagers | |||

|

||||

An illustration of hop cones from Twenty-five Years of Brewing

Cultivating the hops

Before the 20th century, change took place very slowly. It only began to speed up with the spread of the Industrial Revolution and increased economic strength. The time between discovery and implementation is often measured in centuries. Part of this must surely be because time, and its most efficient use, is at the forefront of human consciousness. The plant itself is native to northern temperate zones in West-Central Asia, Northern Europe, and North America where it grew wild. Now hops are under human care as a cash crop, nurtured and looked after in much the same manner as grapes.

The use of hops spread out of Central Europe, carried along by the monks who were then the brewers in society. Their use was late arriving in England, where brewers stuck to other traditional means of spicing beer. As a bittering agent and as a preservative, which is what brewers were searching for all along, hops are superior to all other plants. Due to its qualities, it became the standard brewers settled on. Upon standardization, the uniformity of beer narrowed somewhat, though not completely, due to the vast varieties of hops available, diverse in their aromas and their bitterness.

There are three categories of hops from which brewers can choose. The choice is dictated by the use (and tradition) which they are intended. The three categories are copper hops, late hops and dry hops.

Copper hops are used in the boiler, i.e., the copper (the boilers of old were made of copper, hence the name). Copper hops are usually high in alpha acid, the bittering agent. When used in the boiling stage, fewer high–alpha acid hops than low–alpha acid hops are needed per brew volume, making them more economical.

Late hops are used just at the end of the boil, usually within the last 5–15 minutes, to restore much of the aromatic and flavor-giving elements that are driven off during the boil. These elements evaporate very quickly when heated. They are also called volatiles.

Dry hops are inserted in the primary ferment, the secondary ferment, or in the cask directly after filling. The purpose of dry hops is to add additional aromatic properties to the beer.

See HOPS.

The process of boiling wort so that proteins, carbohydrates, polyphenols, hop acids, and other substances coagulate in the wort and settle to the bottom of the brew kettle, contributing to the trub, which is the undesirable material that should be left in the brew pot when the brewer racks off the fermenter. The trub is approximately 40 to 65 percent proteins; 5 to 10 percent each carbohydrates, bittering substances, and polyphenols; and 1 to 2 percent fatty acids. Some brewers recommend skimming trub off the wort as it forms in the boil.

Decoction mashes break down the proteins to a greater extent, resulting in less trub. Additives such as Irish moss are often added to the kettle to encourage the coagulation of proteins and to force more material to drop out of suspension. The trub can be removed by filtering the wort through a hop back or by using a whirlpool.

See COLD BREAK and TRUB.

A stainless steel tank in which the brewing liquor is treated (if necessary) and heated to the mash strike temperature. This tank can be heated using electricity, gas, or steam, and its temperature is thermostatically controlled.

The addition of oxygen to the wort during its production. Aerating hot wort causes melanoidins and tannins in the wort to become oxidized, which can result in a stale flavor in the beer. Hot side aeration can be avoided by treating the wort gently during its production, especially when collecting sparge runoff from the mash and after boiling, when chilling the wort. Many brewers do not feel that hot side aeration is very significant.

A relatively large regional brewery (capacity 450,000 barrels) founded in the mid–19th century, Huber now produces a dizzying array of brands (many of them passed down from other now-defunct regionals). Among these are Alpine, Bavarian Club, Berghoff, Berghoff Dark, Berghoff Bock, Berghoff Light, Bohemian Club, Boxer Malt Liquor, Bräumeister, Bräumeister Light, Dempsey’s Ale, Holiday, Huber, Huber Bock, Hi-Bräu, Regal Bräu, Van Merritt Light, Wisconsin Club, Wisconsin Gold Label Malt Liquor, Old Chicago, Rhinelander, and Rhinelander Bock.

Huber once produced Augsburger, a celebrated midwestern specialty beer. The company sold the label to Stroh, which now makes a full line of all-malt specialties and seasonals under the label.

See FRUIT, VEGETABLE, HERBAL, AND SPECIALTY BEERS and REGIONAL BREWERY.

Hudepohl-Schoenling is the ungainly name that resulted from the 1986 merger of two grand old Cincinnati breweries, Hudepohl Brewing Co. and Schoenling Brewing Co. (Hudepohl Brewing Co. was founded in 1855 and Schoenling in 1934). Now fondly known as “Cincinnati’s Brewery,” the company brews a variety of local brands in a large utilitarian plant in the heart of the city.

Hudepohl-Schoenling was one of the first of the old-style regionals to brew a revivalist all-malt lager, a brand called Christian Moerlein (named after another historic Cincinnati brewer), and its darker cousin, Christian Moerlein Double Dark. The company also has made hay in the contract market, brewing a variety of beers and malt-based coolers for private labels. More recently, the brewery has turned to nonalcoholic beverages in a big way and has become a substantial producer of packaged teas. This adaptable brewer also serves as an importer for a number of European labels, including Mackeson Stout.

Christian Moerlein Double Dark

This dark, malty lager made its debut when characterful beers were few and far between in the Midwest. Today it has more competition in the specialty beer arena, but it remains a solid entry.

See LAGER ALE and REGIONAL BREWERY.

Founded in 1836, Hurlimann has an annual capacity of 700,000 hl. The company’s primary products are Hurlimann, a lager; and Sternbräu and Hexenbräu, dark lagers. The brewery may be best known for its Samichlaus, imported into America by Phoenix Importers, Ellicott City, MD.

See LAGER ALE.

Samichlaus

A contender for the title of strongest beer in the world. At 13 to 14 percent alcohol by volume, it is stronger than most wines. Samichlaus is a very sweet, malty, heavy-bodied beer. Rich and heady, it is best suited for sipping by a roaring fire after a long day of strenuous activity. More than just a beer, it could be marketed as a restorative tonic.

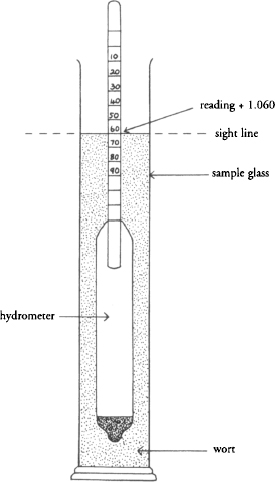

A floating instrument used for determining the specific gravity of a liquid. Normally made of glass, it is weighted at one end. The stem of the instrument is graduated to indicate the gravity of the liquid in which it floats.

Reading the hydrometer

Temperature corrections for hydrometer readings

It is used in breweries for monitoring the specific gravity of wort and beer. In this case, the gravity is specific for sugar levels, hence the term saccharometer.