See GERMINATION SYSTEMS FOR BARLEY.

A beverage made with strong ale, sugar, spices, and roasted apples. From the Anglo-Saxon waes hael, “Be well.”

In 1732, Sir Watkin W. Wynne prepared what is considered to be the first wassail bowl cocktail in Oxford, England. Into an immense silver-gilt bowl was placed a pound of Lisbon sugar, on which was poured 1 pint of warm beer. A little ginger and nutmeg were then grated over the mixture, and 4 glasses of sherry and 5 pints of beer were added to it. It was stirred and sweetened to taste, then covered and let stand for 3 hours. Three or four slices of toast were placed on the creaming mixture, and the wassail bowl was ready. Two or three slices of lemon and a few cubes of sugar rubbed on a lemon peel were added just before serving.

The custom of wassail is quite ancient.

Wassail bowls have been used for thousands of years.

Groups of young people who would visit the homes of their friends in the early hours of New Year’s Day, carrying bowls of spiced ale, were referred to as “wassailing.” The original wassail bowl was presented to Jesus College of Oxford in 1732 by Sir Watkin W. Wynne. However, bowls of varying capacities have apparently been used to drink beer and ale for thousands of years, based upon pictograms and ancient writings.

An ancient pagan custom surviving well into Christian times in which country people poured offerings of ale on prize fruit trees, crop fields, and other agricultural areas. Additionally, prize cattle, sheep, and other livestock were given offerings of holiday brew. The purpose was to ensure fertility in the growing and breeding season to come.

All water is made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. But, all water is not alike. Suspended chemicals, salts, minerals, and other elements can be present and can alter the characteristics of beer. There is also a difference between well water and surface water, which is prone to contamination from farm use chemicals and other airborn matter. If the water comes from a municipal water supply, it will contain chlorine to control bacteria. Well water is preferred because it is most likely to contain desired salts, especially calcium. Calcium stimulates yeast growth and fermentation and aids yeast precipitation. Change the water and you change the beer.

Burton-on-Trent, England, and Dortmund, Germany, are two breweries with unique water supplies which have adapted to local conditions to produce unique beer styles.

Water is not the only reason these two cities prospered as brewing centers. Location and easy transport access are important to their brewing success, but the unique waters defined the classic styles of beers. Water’s impact on the taste of any beer is subtle, but minerals in water do enhance the sensation of bitterness.

Breweries are often the largest commercial users of water wherever they are located. Brewers use vast quantities of water to make beer, since beer is mostly water.

There has been a movement among brewers in North America and elsewhere to develop ways to decrease the amount of water they use that gets turned into waste-water via their sanitation processes, and waste yeast and trub disposal. Every gallon saved reduces brewery operating costs at both ends. On the front end is their water bill, if on a municipal system, or their electric bill if they are pumping water from their own wells. On the back end are sewerage disposal and treatment charges. Water conservation makes good sense environmentally and is good business practice.

Water is not as stable as one might think. Any given amount of pure water contains a certain number of hydroxide ions (OH−) and hydronium ions (H3O+, or simply H+). At 77°F (25°C), the concentration of both of these hydroxide and hydronium ions in pure water is 0.0000001 moles per liter. This is said to be a neutral pH (power of hydrogen), or pH 7, which is a perfect balance.

|

||||

| Common Ions Found in Water | ||||

| ION | TOLERABLE LEVEL | |||

|

||||

| Calcium | 50–100 ppm | |||

| Carbonate/Bicarbonate | 50 ppm | |||

| Chloride | 100 ppm, light beer; 350 ppm, dark beer | |||

| Copper | 10 ppm | |||

| Fluoride | 10 ppm | |||

| Iron | 10 ppb or less | |||

| Lead | 20 ppb or less | |||

| Magnesium | 10–20 ppm | |||

| Manganese | Trace (do not add) | |||

| Nickel | Trace (do not add) | |||

| Nitrate | 20 ppm or less; has no effect but is not needed | |||

| Nitrite | Trace or less | |||

| Potassium | 10 ppm or less | |||

| Silicate | 10 ppm or less | |||

| Sodium | 75–150 ppm; do not use with sulfates | |||

| Sulfate | 75–150 ppm; do not use with sodium | |||

| Tin | Trace | |||

| Zinc | Trace | |||

|

||||

In homebrewing, the pH of mash must be within the ideal range of 5.3 to 5.5 for the best possible extraction. If the water contains too high a concentration of bicarbonates, the mash will not reach this pH range unless dark roasted grains, which tend to be acidic, are added or the water is treated. Fortunately, when this becomes a potential problem, bicarbonates can be precipitated out of the wort by boiling or adding slaked lime.

The pH itself is not as important as the ions. As compounds dissolve into the water, they break up, or ionize, into their component elements. For example, sodium chloride (NaCl) will form one sodium ion (Na+) and one chloride ion (Cl−). The OH− and H+ ions are highly reactive and will react with other ions that are introduced in the solution. When the balance between the OH− and H+ ions is changed, the solution is no longer at a neutral pH.

Malt contains complex soluble phosphate compounds, or salts, which are somewhat acidic. They will react with other ions in the water. If the water is high in bicarbonates, the weak acid from the phosphate compounds will be neutralized. If, however, the phosphates react with calcium, they will precipitate out of solution, leaving an increased number of hydrogen ions and acidifying the mash.

See BICARBONATES and pH.

Weihenstephan, the state brewery of Bavaria (Bayerische Staatsbräuerei), is said to be the oldest brewery in the world. Historical records show that monastic brewers began producing beer at the site in 1040 A.D., and continuing until modern times.

The brewery was eventually secularized and was owned by the Bavarian royal family for a time. It is now a commercial venture, operated by the state government of Bavaria. A state-run brewing college is also located at the site.

The brewery produces a range of world-renowned wheat beers, some of which are available in the United States through Bavaria House Import Co. of Wilmington, North Carolina. These brands include Weihenstephan Weizenbier Crystal Clear, a golden wheat beer; Weihenstephan Hefe-Weissbier, a Bavarian-style wheat beer sedimented with yeast; Weihenstephan Hefe-Weissbier Dunkel, a dark wheat beer, also sedimented with yeast; and Weihenstephan Lager.

See WHEAT BEER and YEAST.

See BERLINER WEISSE and WHEAT BEER.

See BOCK BEER and WHEAT BEER.

See PALE ALE.

A grain that is used in some beer styles in either malted or unmalted form. Malted wheat is used for approximately 50 to 70 percent of the grist for a German weizen (wheat) beer. Unmalted or raw wheat is used for about 40 percent of the grist for a Belgian wit, or white. American wheat beers are derived from the German styles and use anywhere from 25 to 70 percent wheat in the grist. Wheat is almost always used in combination with barley.

Wheat presents several challenges to the maltster and brewer. It is difficult to malt, grind, and sparge. Much of the problem lies with the lack of husk; this makes the grain fragile during the malting process and makes it form a tighter grain bed, which sometimes results in stuck sparges. Wheat is higher in protein than barley, giving it better head retention properties but also a tendency to produce cloudiness. (Winter wheat is usually preferred because of its lower protein content.) A small amount of malted wheat can be added to the grist of other styles to increase head retention.

See ACROSPIRE, MALT, and WHEAT BEER.

A beer made in the usual fashion but with a significant portion of wheat or wheat malt to replace the usual barley malt and other cereals. There are four major wheat beer styles: Belgian white, north German white, Bavarian white, and American wheat.

Wheat beers (sometimes called white beers) are a throwback to the old days, when both wheat and barley were used to make beer. Wheat beers were so common in the Middle Ages that most of the wheat crop went into beer and frequently little remained for bread. This was one of the reasons for the Reinheitsgebot (pledge of purity) of 1516. Partly an effort to force brewers to use barley for beer and leave the wheat for bread, it was notably unsuccessful in that regard.

Many Belgian beers are made up of significant amounts of wheat, most notably those in the lambic group. Another white beer, called wit, is similar in some ways to the Berliner weisse style. Louvain white, an old style, was traditionally produced with 5 percent oats, 45 percent wheat, and 50 percent green (air-dried rather than kiln-dired) barley malt and rolled wheat. The mash on this style is held for an especially long protein rest. This results in very cloudy beer, lending itself to the name white.

The white beer style is gaining popularity today, especially in the United States and the Netherlands, thanks in large part to the popularity of the microbrewery movement and the experimentation by these brewers with the old styles of beer.

The Great American Beer Festival guidelines for Belgian White beers are 11–12.5/ 1.044–1.050 OG (4.4–5.0 Belge), 4.8–5.2 percent alcohol by volume, 15–25 IBU, and 2–4 SRM.

In northern Germany, white beers have a faintly tart overlay. Pinkus Weizen is a good example of that type. An organic beer, it is available in the United States. It is especially refreshing on hot days with a slice of lemon or a dash of schuss, as is done with Berliner Weisse.

The Bavarian white beer, called Suddeutche Weizenbier, is the most popular of the German white styles. It is the one being exported in large amounts to the United States. Bavarian white beer is made with a mixture of barley malt and about 40 to 60 percent wheat malt. The beer is an ale — that is, top-fermented — but aged as a lager, which helps rid the beer of albuminoids, or heavy proteins. This produces a much clearer product than might have been made in the Middle Ages.

The typical Bavarian white beer has a very distinctive palate because of the special yeast used, which gives it a phenolic taste reminiscent of cloves. This comes from 4 to 6 ppm of 4-vinylguaiacol, an ester imparted to the beer by the yeast in the fermenting process. The clovelike flavor adds to the charm of this beer.

Bavarian white beers are often served with a slice of lemon so that the drinker can squeeze a few drops of lemon juice into the beer. Many people, however feel that lemon detracts from the beer’s flavor.

Wheat beers are always top-fermented by a yeast that works at warm temperatures (58° to 65°F, or 14° to 18°C). They are aged lager-style at near freezing temperatures.

Two finishes are available: kristalklar, the filtered version, and hefe-trub, with yeast (hefe) sediment (trub). The latter type is bottle-conditioned by the addition of kraeusen (fresh beer wort) and bottom-fermenting yeast. The wheat in the beer gives this style an especially thick and foamy head. Bavarian wheat beers range in alcohol content from around 5 percent by volume to as high as 7.6 percent in the weizenbocks. Some are amber and even dunkel (dark).

The Great American Beer Festival guidelines for Weizen/Weissbier Ale are 11.5–14/1.046–1.056 OG, 4.9–5.5 percent alcohol by volume, 10–15 IBU, and 3–9 SRM. The phenolic clovelike flavor is necessary, at least 50 percent wheat malt must be used, and the beer should be highly carbonated. The Dunkelweizen subcategory is similar but darker in color (16–23 SRM). Another subcategory, Weizenbock Ale, calls for 16–20/1.066–1.080 OG, 6.9–9.3 percent alcohol by volume, similar hopping rates, and 5–30 SRM.

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | FINAL GRAVITY | ALCOHOL BY VOLUME | IBU | SRM |

|

||||

| Ayinger Export Weissbier (Bavaria) 1981 | ||||

| 12.7/1.051 | 2.5 | 5.2% | 10.5 | ≈7 |

| Hibernia Dunkel Weizen (Wisconsin) 1986 | ||||

| 13/1.052 | 3.6 | 4.9% | 20 | ≈18 |

| Paulaner Hefe-weizen Alt Bayerisches Brauart (Bavaria) 1986 | ||||

| 13.2/1.051 | 2.7 | 5.3% | 18.5 | ≈7 |

| Pinkus Weizen (northern Germany) 1984 | ||||

| 11.1/1.044 | 1.7 | 4.9% | 25 | ≈3.5 |

| Schramm Weizenbock (Germany) 1888 | ||||

| 17.9/1.074 | 6.8 | 5.6% | 20 | Unknown |

American wheat beers draw on the tradition of the Bavarian wheat style. American wheat is distinctively less assertive in flavor, and it is fermented with regular ale yeast; it therefore lacks the clove taste common to its Bavarian counterpart.

Craft brewers have brewed amber wheat beers, dark wheat beers, and even wheat bocks and fruit-based wheat beers. The style allows for much creativity. Basic ingredients are 50 to 60 percent 2-row barley malt and 40 to 50 percent wheat malt. Characteristics are 9.5–12.5/1.038–1.050 OG, 3.5–5 percent alcohol by volume, modest hop levels of 12–20 IBU, and 2–16 SRM. A wheat bock should be at least 16/1.066 OG and 6 percent alcohol by volume.

The Great American Beer Festival guidelines for American Wheat Ale or Lager are 9.5–12.5/1.036–1.050 OG, 3.5–4.5 percent alcohol by volume, 5–17 IBU, and 2–8 SRM.

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | FINAL GRAVITY | ALCOHOL BY VOLUME | IBU | SRM |

|

||||

| Anchor Wheat (California) 1985 | ||||

| 11/1.044 | 1.5 | 5% | 25 | ≈3.5 |

| August Schell Weiss (Minnesota) 1985 | ||||

| 11.5/1.046 | 3 | 4.5% | ≈16 | ≈3.5 |

| Pyramid Wheaten (Washington) 1985 | ||||

| 10/1.040 | 3.2–4.0 | 2.3–1008% | 15 | 3.5 |

| Widmer Weizen (Oregon) 1986 | ||||

| 11/1.044 | 2.1 | 4.4% | 18 | ≈5 |

| American Weissbeer 1900 | ||||

| 9.3/1.037 | 2.5 | 3.6% | ≈27 | Unknown |

The most popular of the new American wheat beers is a draught hefe-weizen from the Widmer Brewery in Portland, Oregon. Brothers Kurt and Rob Widmer began their draught-only brewery in the spring of 1984 with the production of a Düsseldorf-type altbier. Their first seasonal beer, a filtered wheat beer called Widmer Weizen, met with almost instant success. It soon became the most popular of the brewery’s beers. The following year, Widmer offered the weizen as an unfiltered hefe-weizen and suggested serving it in the Bavarian mode, with the special glasses and lemon wedges. This new brew was even more successful. There was no clove taste, which may have been the reason for the beer’s success. It had a mellow, unassertive taste profile and a very pale, cloudy color. It quickly became a gateway beer for anyone wishing to try the new microbrewed beers without worrying about the heavy, hoppy taste of other new “ales,” which was quite unfamiliar to Americans at that time.

The Widmer hefe-weizen became a cult beer in Portland and helped make the fledgling Widmer Brewery into the largest producer of draught-only beers in the country. American hefe-weizen has become a popular beer type brewed by most small craft brewers and brewpubs in the country.

See BELGIAN WHITE BEER, BERLINER WEISSE, and BOTTLE-CONDITIONED BEER.

A cylindrical, vertical, stainless steel tank used for to separate the hop/trub from the boiled wort. This is the separation method when hop pellets, powders, or extracts are used instead of whole hops in the brew kettle.

Wort from the brew kettle is pumped around the circumference of the whirlpool at high speeds to create a whirling effect. Centrifugal force throws all the hop residues and precipitated proteins to the middle of the vessel. These settle to the bottom, allowing the bright wort above the trub to be run off. The bottom of the vessel is generally slightly conical, although some vessels are flat or have a well-shaped bottom.

The brew kettle is often combined with the whirlpool. The boiled wort is taken from the bottom of the cone base and returned about one-third of the way up the straight side through a tangential return. The internal whirling effect that is created results in separation of the boiled wort and the hop residues.

Founded in 1842, Whitbread became a public company in 1880. It is now a large combine, operating six breweries. Among its best-known brands are Whitbread Best Bitter, Mackeson Stout, and Boddington’s Bitter.

Various labels from the bottles of Whitbread PLC brands

Samuel Whitbread, of Whitbread PLC

Whitbread beers are imported to the United States by Hudepohl-Schoenling of Cincinnati, Ohio (Whitbread & Mackeson) and Labatt’s U.S.A. of Darien, Connecticut (Boddington’s).

Whitbread PLC brands from throughout the company’s history

South Hams, as the southern district of Devonshire, England, is locally known, is remembered for once preparing white ale. It used to be brewed with malt, a small quantity of hops, flour, spices, and grout (also called ripening). As there are different recipes for grout, these ales varied considerably. This beer is not available today from any commercial brewer.

See BELGIAN WHITE BEER, BERLINER WEISSE, and WHEAT BEER.

A special Burton-brewed India Pale Ale (IPA) unveiled at The White Horse at Parsons Green, London, on July 31. This memorable event, which provoked much press coverage, developed out of a seminar Mark Dorber, cellar manager (and now publican) at The White Horse, organized in July 1990. Four Burton brewers at the seminar had the idea to try to recreate a late 1800s IPA. In April 1993, in cooperation with Gus Gutherie, technical director of Bass Brewery, they reproduced a classic IPA. Tom Dawson, a retired Bass brewer agreed to act as consultant. To formulate this joint effort, Mr. Dawson consulted Bass’s brewing ledgers back to the 1880s.

White Horse IPA

An India Pale Ale with 7.0 percent alcohol by volume, original gravity 1.064, 85 IBU.

It contains 90 percent halcyon malt, 10 percent brewer’s sugar, progress whole hops in copper, and Kent Goldings for dry hopping.

The strong hops overpower any other bouquet. It has a long-lasting hop flavor. The color is 18 SRM.

The White Horse IPA boasts a lovely big white head, and because the Progress hops used had a higher-than-normal alpha acid content (7 percent versus a more normal 5 percent), the bittering units imparted were 40% more than what might be expected.

The White Horse IPA was brewed in the Bass Brewery Museum brewhouse, begun in 1920. This lovely example of a tower-type plant was transported in the late 1970s to the Bass Brewery and installed in an old engine house, now within the confines of the museum. The plant has a 5-barrel capacity. Two brews or batches were necessary to fulfill a White Horse beer festival order of “at least six-hogsheads.”

At joint team made up of young Bass brewers and cellarmen from The White Horse assembled at 6:00 A.M. on Saturday, 19 June 1993 at the brewery. Twenty-nine hours, two brews and a clean-up later they were done. Then it was up to the yeast to do its work.

The resulting beer was a hop-lover’s delight. To those fortunate enough to have some, it will remain, surely, a most memorable ale.

See INDIA PALE ALE (IPA).

After the success of the first event in November 1994, promoters planned to make this an annual event and lined up the June 1995 festival for the Century II Exhibition Hall in downtown Wichita, Kansas. The promoters, Standard Beverage Corporation, happen to be beer distributors, but the 65 offerings at the festival were not limited to their beers. The festival raised $22,000 for the local leukemia society.

Widmer Brewing Co. operates out of a sizable draught-only plant and a new building in which bottled beer is produced. The company has built a market for its hefe-weizen (wheat beer with yeast) in its hometown and is now expanding the style into other western metropolises.

The company was founded in the early 1980s by two brothers, Kurt and Rob Widmer. Kurt developed an appreciation for German beer while living and working in Germany during the 1970s. He experimented with homebrewing for several years, then established Widmer Brewing Co. in 1984. The company built a second brewery in Portland in 1988, then 2 years later moved its operations to an historic building in north Portland, expanding its capacity substantially. A 120-keg-per-hour filling line was added in 1993. The company’s 40-barrel brewhouse churned out a record 50,000 barrels in 1994.

Widmer Hefe-Weizen

Made with a strain of yeast from Germany’s famous Weihenstephan brewing school, Widmer Hefe-weizen has taken the Portland market by storm. A golden, cloudy beer, it is kegged unfiltered directly from the fermenters, leaving yeast in suspension. This beer is rich in flavor and B-complex vitamins. It is a clean, quenching brew.

Most recently, Widmer has contracted to have Widmer beers produced at a state-of-the-art brewery operated by G. Heileman in Milwaukee. This agreement will give Widmer the ability to expand its beer into the midwestern and eastern markets.

In addition to hefe-weizen, the company produces weizen, Märzen, Oktoberfest, and bock, using the traditional German altbier brewing style, which combines ale and lager brewing techniques. Widmer beers are top-fermented and cold-conditioned.

See MICROBREWERY, WHEAT BEER, and YEAST.

See LAMBIC and SPONTANEOUS FERMENT.

Any yeast other than the specific strain of Saccharomyces the brewer has chosen to use. Wild yeasts impart off-flavors, as they ferment sugars that Saccharomyces strains do not. If they are large enough in number, they can ruin a batch of beer with off-flavors and off-aromas. The best defense is good sanitation procedures, a pure strain of brewing yeast, and high pitching rates.

See FESTBIER.

See BELGIAN WHITE BEER and WHEAT.

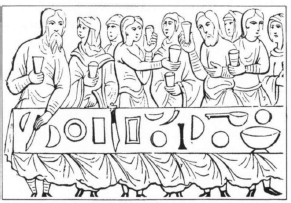

Until the Middle Ages, the brewing of beer was exclusively the province of the woman in the household. Old laws even went so far as to state that the vessels used in brewing were her personal property. As far back as 2000 B.C., Mesopotamia (part of modern Iraq) acknowledged women as brewers in an industry that even then was held in the highest regard. In Babylon, female brewers, or brewsters (the feminine form, just as baxter and spinster are the feminine forms of baker and spinner), were priestesses in the temple, giving the industry an ecclesiastical flavor that continued to the monastic breweries of medieval England. The ancient Finns preserved their accounts of the creation of the world in a song and story cycle known as the Kalevala. Historians date the beginnings of these poems and legends to as early as 1000 B.C. For the Finns, beer was born through the efforts of three women preparing for a wedding feast. Osmotar, Kapo, and Kalevatar all labored to produce the world’s first beer, but their efforts fell as flat as the brew itself. Only when Kalevatar combined saliva from a bear’s mouth with wild honey did the beer foam, and the Finns received gift of ale.

Beer was often advertised as being so nourishing that nursing mothers were encouraged to drink it. Today, some groups still advocate the drinking a stout or porter white nursing, although the medical establishment has not embraced this theory.

Depicted here as a tavern sign, originally the “good woman” representation referred to some female saint, or a holy or good woman who had met death by the privation of her head. Also called the “silent woman,” it evolved to become a tasteless joke.

Women brewed and enjoyed beer throughout the ages, as this print (ca. 1800) illustrates.

In thirsty post-Roman times, the Anglo Saxon bredale, which means “bride,” was a prominent part of the marriage ceremony. The bride’s family brewed a special ale for the occasion. The term “Bridal Ale” lives on in our present-day usage, bridal. During medieval times, as monasteries began brewing beer on a larger scale, women’s involvement in the brewing process gradually diminished and finally came to an end, as more and more, the man became the brewer in the home.

The Industrial Revolution struck a final blow to the ale wife, who sold unhopped beer with a shelf life of a few days from her brewpub. Men have tended to do the brewing ever since. Modern marketers, too, suggest that beer is a “man’s” beverage. That belief may be changing, however, as more women come to regard brewing as an ancient craft of great culinary value, the successful accomplishment of which is in no way sexist.

The position of brewer at Pinkus Muller in Munster has been handed down from father to son since 1811. Pinkus now has a brewster, Barbara Muller, daughter of Franz Muller and granddaughter of Pinkus Muller. Significantly, Pinkus became the modern world’s first organic brewery since Barbara’s arrival. She attended Weihenstephan, the oldest brewing university, and reports increased enrollment for women seeking degrees.

The unfermented mixture of water, sugars from malted barley, and hops. The term usually refers to this mixture during the boiling process. During the sparging operation, before hops are added, the liquid is referred to as “sweet liquor.” After the boil is finished and the wort is chilled and moved to the fermenter, it is usually referred to as “unfermented beer.” Once fermentation is complete, it is “beer.”

See KRAEUSENING/WORTING.