CHAPTER 1

Wye Valley Themes

THE RIVER

THE WYE RISES HIGH on the slopes of Plynlimon, just 2km from the source of the Severn, and flows some 225km through the Welsh borderland into the same Severn at Chepstow. Starting, like any other mountain stream, as a slight, rocky defile flowing through sheepwalk, it collects several tributaries before Llangurig and develops a more mature, tree-lined course. As it passes Rhayader and Builth it flows in a broad floodplain as clear water over a rocky bed, through a broad, arborescent valley in the shadow of the Cambrian Mountains. From Boughrood downwards the hills stand back. Indeed, Glasbury, with its modern concrete bridge and broad riverside meadows, could almost be by the middle Thames, so complete is the feel of the lowlands. At the Welsh border Lord Hereford’s Knob, Hay Bluff and Merbach Hill bring the uplands close again, enabling the book-lovers of Hay and the Kilvert enthusiasts of Clyro to mix with the walkers in the Black Mountains. Thereafter, through Monnington, Hereford, Fownhope and Ross, the river glides smoothly between deep, alluvial cliffs among what were once the meadows and pastures of a broad floodplain until, below Hereford, the meanders become so sweeping that peninsulas of farmland are linked to the rest of the world only by narrow lanes and footpaths over neat suspension bridges.

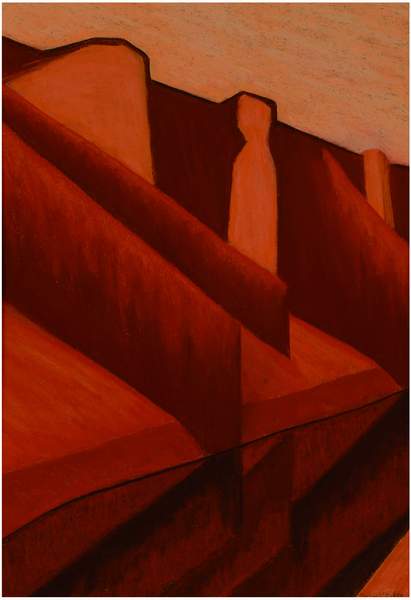

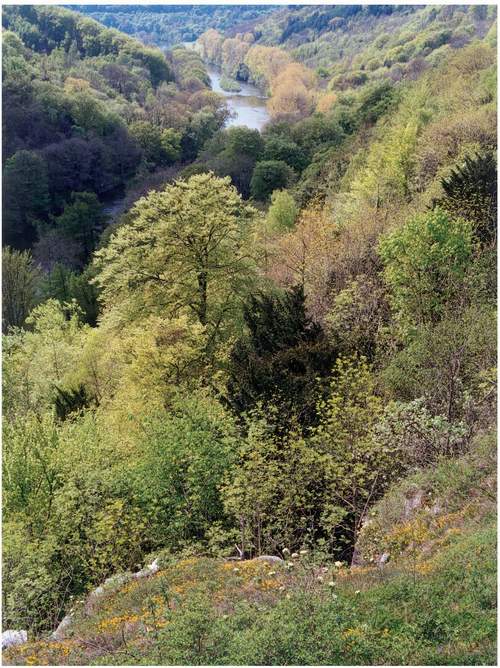

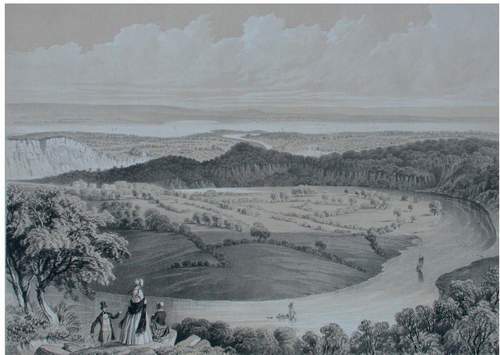

From this point onwards, any other river would flow in a broadening channel through an industrial city into a wide estuary, but not the Wye. Instead, in an extraordinary transformation, this mature lowland river flows directly into the hills. More surprising still, after sweeping past the Bicknors, it flows out into the lowlands, only to turn back again into the hills. Thus, from Symonds Yat Rock, a glance to the east shows the famous view of the Wye flowing out between Coppet and Huntsham Hills (Fig. 1), but a glance to the west shows it flowing back in again below the Doward. Thereafter, it runs through a wooded defile past great cliffs and limestone pillars to Monmouth. Winding sinuously between steep wooded banks, it eventually reaches Tintern, below which the cliffs again stand out among the woods. This, the lower gorge, finishes against sheer limestone cliffs below the curtain walls of Chepstow Castle. Then, after passing the new Chepstow bandstand and abandoned wartime shipyards, the river flows unnoticed into the Severn in the shadow of one the world’s great suspension bridges, England on its left bank, Wales to the right.

That is the Wye, arguably the finest and least spoiled of all the major rivers of Britain. It is also the ‘unknown’ river, for, despite its qualities, it has attracted relatively little attention. Indeed, it is probably less famous now than it was

FIG 1. The iconic view from Symonds Yat Rock, with Huntsham Hill woodlands to the left and Coppet Hill in the distance to the right. The Wye at this point is flowing north towards Goodrich (visible in the distance), but it turns left and flows back behind the photographer into the gorge. The mixed ash-beech-lime-wych elm woodland below has now grown from coppice into the rugged canopy that must have characterised prehistoric woodland. Photographs of this view are so numerous that detailed long-term studies would be possible of canopy change, scrub invasion of Coppet Hill, hedge deterioration and even the changing configuration of cattle tracks in the gateway below.

nearly 240 years ago, when a parish priest from the New Forest hired a boat at Ross, drifted down to Chepstow, wrote his Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, &c. (Gilpin, 1782), and thereby established the Wye Tour. More recently, among a medley of light topographical works, we have more historical and descriptive substance in Mr and Mrs Hall’s Book of South Wales, the Wye, and the Coast (1861), the paintings of Sutton Palmer in A. G. Bradley’s The Wye (1910), Keith Kissack’s delightful The River Wye (1978) and John Wilford’s line and wash drawings in Edmind Mason’s Wye Valley (1987). For over 150 years, the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club has encouraged and recorded an interest in the geology and natural history of Herefordshire and the Lower Wye, and nearly 90 years ago a local doctor, W. A. Shoolbred, compiled his Flora of Chepstow (1920). Despite these and other writings, the valley and its surroundings are not well known. Indeed, until recently, any naturalist whose knowledge was confined to the ecological literature would have been almost unaware of the existence of the woods by the Lower Wye, one of the finest aggregations of ancient woodland in the whole of Britain.

This book is about the Lower Wye and its associated countryside, in effect the district from Hereford southwards, its history, natural history and conservation. Since 1970, the valley from Fownhope to Chepstow, and its immediate surroundings, has been recognised officially as the Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), but the book ranges further into the Forest of Dean, down to the Severn, up the Monnow valley and the Wye above Hereford. Its focus is the gorge, but comparisons are also made with the more ordinary countryside of the Herefordshire lowlands, and attention is drawn to some of the important places nearby. Sadly, space is insufficient to cover the upper Wye as well, though some characteristics that influence the river throughout its length are mentioned.

What is it about this region that makes it so distinctive and rich, yet relatively obscure? Many travellers come to see Hereford Cathedral, the chain library and the Mappa Mundi, and there are often crowds at Symonds Yat and Tintern Abbey, but on the whole holidaymakers go elsewhere, speeding on to the coast or the mountains. Likewise, those natural historians and ecologists who have not been confined to their locale or their laboratory have usually been attracted by extremes, leaving the above-average, not-so-distant, still-almost-ordinary habitats to themselves. This is a pity, for the Lower Wye Valley and its surroundings have fine landscapes and much to offer natural historians.

BORDERLAND

We who live around the Lower Wye gorge are particularly aware that we are part of a borderland. The river forms the boundary between England and Wales, and most of the Wye flows through the region broadly known as the southern Welsh borderland. To drive up the lowest part of the valley is to cross national boundaries several times. Residents on the Gloucestershire side habitually shop in Wales. When they fall ill, their nearest hospital is in Chepstow (Monmouthshire). Uniquely, the AONB overlaps two countries and three counties, with separate administrations, different County Plans, different kinds of grant aid for countryside management, and very different relationships with central and regional government. More complicated still, the national boundary leaves the river at Redbrook and runs on the ‘English’ side through the woods to the Biblins Bridge in the upper gorge. Among other consequences, this places some Welsh woods under the administration of the Forest of Dean (England), and Lady Park Wood National Nature Reserve, which sits astride the boundary, finds itself managed by both Natural England and the Countryside Council for Wales. Conversely, the entire Wye catchment is administered as part of Wales by the Environment Agency.

In truth, these anomalies are hardly noticed by borderlanders, many of whom feel they belong to a third country, neither England nor Wales. What does matter is marginalisation. To residents, the valley is central to our movements and sense of place, but to local authorities in Cwmbran and Gloucester we are on the edge. Residents on the Gloucestershire bank feel this particularly keenly: viewed from Gloucester, the Forest of Dean is a detached and atypical part of the shire, and the Lower Wye is beyond even the Dean. Moreover, we are lumped in with the Dean, whereas we know that we are historically, socially and ecologically quite distinct. The Lower Wye is also as far from a university as one can get in southern England, though its historic remoteness from centres of learning has been somewhat alleviated by the first Severn Bridge and easy access to Bristol and Cardiff.

Politically, this borderland character has endured for at least a thousand years. The Domesday Book of 1086 records a few details in east Monmouthshire, but under-records the Archenfield district of Herefordshire. Moreover, the boundary between Herefordshire and Gloucestershire was poorly defined in the Dean: Alvington, Redbrook and Staunton – now in Gloucestershire – were in Herefordshire. Chepstow and Monmouth castles are just two of many fortifications that were concentrated along the borderland, where they enforced the will of governments to the east on the people living to the west. Further back, Offa’s Dyke seemingly defined the English-Welsh boundary, but ran on the Gloucester side of the valley, leaving an interesting no-man’s-land between the dyke and the river. Further back still, the promontories overlooking the river were studded with Iron Age encampments.

Patterns of land use and communications contributed to remoteness. In the eleventh century the middle section of the gorge was unclaimed forest subject to common rights, the Dean to the east and Wyeswood Common to the west. In the twelfth century this remoteness attracted the Cistercians to Tintern, where they founded what has latterly become one of Britain’s most popular ecclesiastical ruins. A network of roads connected the settlements, but these were mainly on the plateau: the main roads ran through Trellech and St Briavels, and there was no road along the length of the valley itself. In fact, the true gorges below Tintern and through the woods between Symonds Yat and Hadnock were extremely remote places, cut off as much by the narrowness of the valley as by the limestone cliffs. Remoteness continued into the gentler countryside upriver (Fig. 2), for the

FIG 2. The Wye floodplain at Fownhope Park, a fine example of the remote and peaceful agricultural landscape that characterises much of the Herefordshire part of the Lower Wye. (Photo Chris Musson, © Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club. Millennium Air Survey of Herefordshire. Hereford Record Office)

Hereford floodplain and the spurs of land defined by the river were reached only by minor lanes and ferries, and the land running northwest from Monmouth was the peculiar semi-Welsh district of Archenfield. Remoteness was, of course, relative – until recently, every bit of land was used – but throughout the medieval and earlier periods the river itself was probably the main line of communication.

The Lower Wye Valley is also a borderland in more natural terms. It is close to the boundary between highland and lowland Britain, geologically, climatically and in terms of its characteristic native vegetation. The woods in particular have diverse mixtures of trees and shrubs that are more characteristic of the southern lowlands of Britain, but they also include wet, mossy oakwoods that have much in common with the woods of western Wales. This natural transition can also be seen in the distribution of farming types: the Lower Wye Valley is on the border between predominantly pastoral farming to the west, and mixed farms with much arable to the east. In purely biogeographical terms, several lowland species, such as the marbled white butterfly, reach their western limits here.

However, like so many historically remote regions, the modern history of the Lower Wye Valley has been characterised more by loss of remoteness. This started in 1824 with the construction of the main road, cut from St Arvans through the woods below the Wyndcliff to Tintern. The new road linked existing lanes and crossed the new Bigsweir bridge to join upgraded roads driven through the woods to Redbrook and on to Wyesham. In 1861 the railway was constructed from Chepstow to Monmouth, and thence by other lines to Ross and eventually to Hereford. In 1910 one could just about make a useful day trip to London. (The 9.19 from Tintern connected with a train that reached Paddington by 12.40, but one would then have to return on the 2.30 from Paddington to connect with the last train to Tintern, which arrived as early as 6.54. One could have another 45 minutes in London, but the 3.15 from Paddington would only get one as far as Chepstow.) In 1906 a bridge was thrown over the Wye at Brockweir, thereby connecting a remote and reputedly lawless miniature port to both the railway and the valley road. Eventually, the valley road became the A466, arguably the greatest ‘planning’ mistake ever made in the valley. Admittedly, it helps residents to get around when it is not clogged by convoys of grockles driving serenely along at 25 mph, but it also brings posses of bikers on Sundays, and is only maintained in the face of natural erosion by a great deal of civil engineering with rock blasting, bank reinforcing, tree felling and wire netting over rocks.

Loss of remoteness has been felt in other ways. In recent times, motorways to Ross and Monmouth and Chepstow forged rapid connections to south Wales and the Midlands. In 1966 the Severn Bridge was built as an easy link to Bristol and on to London, now two hours away when the motorways are uncongested. There is now a rush hour even in minor lanes, as a significant proportion of residents commute to jobs in the nearby cities. Pressures for more housing are being met by substantial suburban developments on the fringes of Chepstow and Monmouth. Tourist traffic has increased, requiring large car parks at Tintern, Symonds Yat and Ross, and the upper gorge has a large campsite and a dense network of walking tracks. Proposals for a cycleway along the valley floor have been vigorously debated: dressed up as green transportation, this would require even more parking space in the tourist hotspots. The valley is used regularly by military aircraft for practising low-level flying: it is quite difficult to feel detached when one looks down onto a lumbering Hercules snaking along the line of the river, or when one cowers beneath needle-sharp fighters flying just above the tree-tops.

Despite the losses, much remains. The lower valley is a bastion of land free from light pollution, surrounded by regions where one is rarely out of sight of the glow of city lights. The gorge below Tintern is still unbelievably remote, despite the occasional and permitted presence of water-skiers. Archenfield and the gentle valley above Ross must remain as tranquil as any stretch of farmland in southern Britain.

LANDSCAPE, TOURISM AND THE PICTURESQUE

During the eighteenth century the Lower Wye Valley became so famous for its scenery that it attracted hosts of visitors to the Wye Tour (Whitehead, 2005; S. Peterken, in press). ‘Natural’ landscapes were increasingly appreciated by men and women of taste, estates were moulded to reflect this appreciation, the countryside became more accessible on the new turnpikes, a tourism industry developed to cater for tourists’ needs, and vistas and walks were built to afford access to the finest views. The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars discouraged aristocrats and the burgeoning upper middle classes from Grand Tours on the Continent, so they visited the Lower Wye Valley, Snowdonia, the Lake District and Highland Scotland instead. The Lower Wye was thus at the centre of a revolution in artistic perceptions and recreational activities.

The key figure was William Gilpin, whose book (1782) set the rules for the ‘picturesque’ appreciation of landscape. In his eyes, the beauty of the landscape ‘arose chiefly from two circumstances – the lofty banks of the river, and its mazy course; both of which were accurately observed by the poet [Alexander Pope], when he described the Wye, as echoing through its winding bounds.’ The views from the Wye were ‘free from the formality of lines’. The folds of the valley sides were an infinite variety of screens, folding over each other. In particular, the Wye’s variety of landform was enhanced by four particular kinds of ornament, ‘ground, wood, rocks and buildings’. By ‘ground’, Gilpin referred to the small-scale variation in landforms, steep slopes, flat ground, rocky outcrops, patches of naked soil, variety of soil colour, small streams, waterfalls, and the ‘rough beds of temporary torrents’. ‘The woods themselves possessed little beauty, and less grandeur’, partly because they were repeatedly cut down and made into charcoal, but the smoke from the charcoal hearths issued from the sides of the hills, and ‘spread its thin veil over a part of them, beautifully breaking their lines and uniting them with the sky’. The rocks were beautiful in themselves, and contrasted variously with the trees, shrubs, water and broken ground. Finally, the ‘abbeys, castles, villages, spires, forges, mills and bridges’ characterised almost every scene, and gave contrast and ‘consequence’ to the beauties of nature.

Gilpin’s aesthetics were part of a major change in human perceptions that started in the seventeenth century and blossomed in the eighteenth. Wild landscapes ceased to be regarded as merely useless and became instead a source of spiritual renewal (Thomas, 1983). By the late eighteenth century wilderness had value, and appreciation of wild nature had become almost a religious act. This change was partly a reaction against urban living and the expanding area of enclosed and cultivated land, but it also embodied a belief in the divinity of nature, the response that formed the foundation of the Romantic movement. British landscapes increasingly became objects of artistic attention, and by the 1760s visitors were flocking to the Lake District, the Wye Valley, Snowdonia and the Highlands in search of exciting scenic effects.

Two contrasting perceptions of landscape coexisted (Wilton, 2002). Sublime landscapes, epitomised in the works of Salvator Rosa, dramatised wild scenery on a grand scale, with impenetrable forests, torrents, irregular rocky precipices and natural forces, such as storms and thundering clouds. They were meant to elicit feelings of solitude, awe and an instinct for self-preservation. Beautiful landscapes, on the other hand, epitomised in the paintings of Claude Lorrain, showed scenery as an elegant balance of smooth, gentle, soft elements, with careful asymmetries in the foreground framing the distance in which light played on woodland and water, and it was these that became the model for landscape designers, such as Lancelot (‘Capability’) Brown. Picturesque landscapes could be either sublime or beautiful, but they had to please as paintings. In Gilpin’s view they required a focus of interest, side-screens, an interesting foreground and distant perspectives.

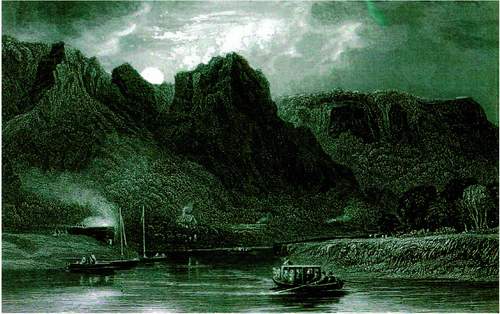

Visitors to the Wye Valley evidently judged the intimate views, framed by the steep valley sides, dominated by wild scenery without the obviously man-made elements of property boundaries and the parallel furrows of cultivated ground, to be picturesque (Andrews, 1989). The most spectacular scenery, such as that around Piercefield and the Wyndcliff, elicited comparisons with both Salvator Rosa and Claude Lorrain, but it lacked balance and intimacy, and was rarely judged to be picturesque. Rather, much of the scenery down-river from Walford was appreciated as sublime, with awe-inspiring vistas of great crags emerging from banks of precipitous woodland, or deep, forbidding gulfs below precarious viewpoints (Figs 3 & 4). (The danger was, in fact, real: one owner of Piercefield House, Valentine Morris, actually fell from the Lover’s Leap, but snagged in some branches and lived.) Early in his career, J. M. W. Turner painted Tintern as over-arching ruins, festooned in threatening ivy.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the works of man were neither ignored nor denigrated, for buildings of all kinds gave ‘consequence’ to the wild, natural scenery. As he floated down the upper gorge, charcoal hearths burned in the woods and filled the valley with smoke, but Gilpin thought this lent depth to the perspective. The woods at that time were felled in patches, and would have looked intensively

FIG 3. Coldwell Rocks by moonlight, 1837. Engraving by W. Radclyffe after David Cox. The tourists are seen in their covered boat, together with other craft. A limekiln is operating at the base of the rocks and small cottages also emit smoke from wood fires. The grandeur of the rocks is somewhat exaggerated, as was customary for artists wishing to emphasise the sublime. Although the rocks are well wooded, the trees are not as tall as their modern successors, which almost obscure the outcrops.

FIG 4. Coldwell Rocks, by Susan Peterken. The Wye Valley has remained popular with artists. In 2006, the Wye Valley Art Society organised a touring exhibition in which paintings by the original tourists were set beside modern works.

managed by today’s standards, but this was rarely criticised. Industrial activity generated excitement. Thus the awesome natural scene at New Weir, where the river was ‘a chasm between two ranges of hills which rise almost perpendicularly from the water’ and ‘the agitation of the current is encreased [sic] by large fragments of rock which have been swept down by floods from the banks, or shivered by tempests from the brow’, was actually enhanced by the iron forge, with its ‘black cloud of smoak [sic]’, half-burned ore, piles of cinders, and ‘the sullen sound, at stated intervals from the strokes of the great hammers of the forge [that] deadens the roar of the water-fall’. This din, combined with the frail ‘little fishing coracles’ and ‘the idea of force or of danger which attend them, gives to the scene an animation…perfectly compatible with the wildest romantic situations.’ Moreover, some natural elements were regarded unfavourably. Thus Young (1768) complained of the Wye at Piercefield that ‘the colour is very bad; it has not that transparent darkness, that silver-shaded surface, which is of itself, one of the great beauties of Nature’; and in 1776 he simply described the Wye as ‘a stream of liquid mud’. A century later Francis Kilvert was distinctly unimpressed by the ‘wastes of hideous mud banks with a sluggish brown stream winding low in the bottom between’ (quoted by Kissack, 1978).

Against this background, it was inevitable that the manifestly man-made remains of Tintern Abbey were greatly appreciated (Fig. 5). The income from tourism persuaded the Duke of Beaufort to preserve the ruins in the inspiring state we find them in today. They not only provided a graceful counterpoint to the wild river and the amphitheatre of natural woodland, but their evident decay brought out melancholy reflections on the ‘pleasurable sadness’ or ‘settled despair’ of the passage of time. The heavy growths of ivy hanging from the east window modified the ‘hurtful’ regularity of the masonry, but not enough, for Gilpin took the bizarre view that the ruins would look less regular and more romantic if bits were knocked off with a hammer. Visitors were thrilled after dusk by sparks ascending from the nearby forges, but they deplored both the rude cottages that had been built around the ruins, and the cottagers’ ‘absurd labour’ in clearing the weeds from the abbey interior and substituting ‘a turf as even and trim as that of a Bowling-green, which gives the building more the air of an artificial Ruin in a Garden, than that of an ancient decayed abbey’ (Francis Grose, quoted by Andrews, 1989). They would not have liked it today!

In 1745 John Egerton, the rector of Ross and a future Bishop of Durham, built a pleasure boat and took his friends for trips on the Wye. By the 1770s, the influence of Thomas Gray (the poet), Paul Sandby (a leading topographical artist), William Gilpin and other early visitors had established the Wye Tour. For a consideration of three guineas, tourists could spend two days gliding down with

FIG 5. Tintern Abbey, the Cistercian foundation that became the focus of tourism in the Lower Wye in the eighteenth century, and which still receives great crowds of visitors each year. Modern photographers may curse the utilitarian farm buildings (left, foreground), but no more so than eighteenth-century visitors, who had to view the abbey church past a fringe of hovels.

the current from Ross to Chepstow, with an overnight stop in Monmouth, attended by boatmen employed to row them past shallows or stop them at landings. Tourists were afforded every opportunity for leisurely contemplation, a smooth passage past steadily unfolding scenery, abundant food, and tables where they could draw what they saw. When William Gilpin made the trip in 1770 he was caught in heavy rain, but the boats were covered and he still managed to sketch the scenery and take notes.

Many tour diaries survive, and one example must stand for them all. In September 1803 the landscape artist, Joseph Farington, did the Tour with his friends Hoppner and Evans, and it did not go at all smoothly (Newby, 1998). Farington left London by coach on the evening of Friday the 9th and eventually reached Ross on the Tuesday, where he stayed at the King’s Arms. He and his companions admired the view from the church, and noted five pleasure craft awaiting passengers on the river, but when they went to the boat next morning they found that the water had never been so low. They proceeded nevertheless, recording impressions of picturesque scenery, disembarking to walk on riverside meadows, ascending to Goodrich Castle, and remarking on the smoke of fern burning (Fig. 111) on the flanks of Rosemary Topping, but the boatmen had to jump into the water repeatedly to manhandle them over the shallows. Near Symonds Yat, even this was not enough, for Farington and his friends had to be carried ashore to reduce the draught still further. Sadly, calamity struck: one of the helpers was drunk and Evans was pitched backwards into the water. Arriving late and presumably damp at New Weir, the travellers elected to walk the rest of the way to Monmouth, but they gave up after two miles, sought shelter with a garrulous and embittered cottager, and called a chaise. They eventually arrived at the Beaufort Arms at 10 p.m.

Next day they took a break. Farington and Hoppner rode back to New Weir to make some sketches, while Evans ascended the Kymin to take tea or coffee in the Summer House. Since the river was so low, they resolved to go to Tintern by road, and next morning set off via Trellech (the main road down the valley being still 21 years into the future). After dutifully viewing the abbey remains and noting the heavy ivy growing over the east window, they rode to the Eagle’s Nest viewpoint and on down to the Piercefield Walks, where they were obliged to borrow some cutlery from Piercefield House with which to eat their lunch.

They lodged at the Beaufort Arms in Chepstow for a few days, sketching the castle and the views from the Walks, noting how at low tide the Wye at Chepstow ran ‘a vast depth of miry bank on which Ships and boats lay dry on the sloping side of the precipitous descent till the returning tide again floats them upon an even surface’. They visited a friend across the Severn and eventually returned to London on Wednesday 28 September. The whole trip cost £15 18s 1112d, including 3s 6d for the Wye book, presumably the guide marketed by Mr Heath (1806). In terms of effort it seems roughly equivalent to a modern holiday in the Australian outback. The lasting product was some paintings, some of which are exhibited in the Hereford Museum and Art Gallery.

Farington and others used particular viewpoints to appreciate the Wye Valley scenery. Those above Chepstow were laid out and embellished in the 1750s as the Piercefield Walks by Valentine Morris, the owner of Piercefield House, and they became a key attraction of the Wye Tour (Whittle, 1992). The house and walks were open to visitors on Tuesdays and Fridays, and this enabled residents and tourists to pass the Alcove, the Grotto, the Double View, the Druid’s Temple, the Giant’s Cave and the Lover’s Leap. The path, which is now part of the Wye Valley Walk, was carefully levelled and hardly arduous, but it was close to the precipice and the romantic sense of danger was enhanced by occasional cannon fire from the mouth of the Giant’s Cave. A detour led down to the Cold Bath, a square dip

FIG 6. Viewing the Wye from the Eagle’s Nest. This is not a group of nineteenth-century revellers, but a twentieth-century excursion by delegates to a conference on forest history.

fed by a small stream in Lower Martridge Wood, and up to the Wyndcliff. After 1828 the ascent to the Eagle’s Nest viewpoint (Fig. 6) was made from Moss Cottage, ‘a fanciful little erection, and a cool and pleasant retreat’ (Clark, c.1875), by means of 365 steps cut into the rock.

The views from the walks over and beyond the confluence of the Wye with the Severn were stupendous. Here, for example, is Arthur Young’s description of the view of Lancaut (Figs 7 & 8) from a large beech tree located between the Grotto and the Pleasant View (Young, 1768):

The little spot over which the beach [sic] tree is spread, is levelled in the vast rock, which forms the shore of the Wye, through these grounds: this rock, which is totally covered by shrubby underwood, is almost perpendicular from the water to the rail that encloses the point of view. One of the sweetest vallies [sic] ever beheld lies immediately beneath, but at such a depth, that every object is diminished, and appears in miniature. This valley consists of a complete farm, of about forty inclosures, grass and cornfields, intersected by hedges, with many trees; it is a peninsula almost surrounded by the river, which winds directly beneath, in a manner wonderfully romantic; and what makes the whole picture perfect, is its being surrounded by vast rocks and precipices, covered with thick wood down to the very water’s edge. The whole is an amphitheatre, which seems dropt from the clouds, complete in all its beauty.

Walking on to the point that sixty years later became the Eagle’s Nest viewpoint, ‘from which the extent of the prospect is prodigious’, Young was even more impressed by ‘the surprising echo, on firing a pistol or gun from it. The explosion is repeated five times very distinctly from rock to rock, often seven; and if the calmness of the weather happens to be remarkably favourable, nine times. The echo is curious.’ Yes, indeed: those who have attended a Bonfire Night in the valley know exactly what he meant.

The most famous words about the Lower Wye were written at the height of the Tour. William Wordsworth’s ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ were penned during his second visit, on 10 and 13 July 1798 (Bentley-Taylor, 2001). They have been described as the locus classicus of Romantic nature worship

FIG 7. The view from the Wyndcliff, by C. J. Greenwood, 1840. Drawn from a point to the south of Eagle’s Nest, the landform and field boundaries seem to be accurately represented. The vertical streaks in the woods, generated by fissures in the limestone and falling trees, are still visible. Since 1840 many field boundaries and most of the boundary trees have gone, and one embayment in the river bank has grown. The highest point on Pen Moel cliffs (left) has been quarried away (see Figs 8 & 144).

FIG 8. The view from the Wyndcliff today. This is the famous Horseshoe Bend, beyond which is Chepstow, the mouth of the Wye and both bridges over the Severn. The field boundaries on the Lancaut peninsula differ in detail from those shown in Fig. 7, and there are fewer trees – but how much is this change and how much is it artistic licence?

(Andrews, 1989), but the descriptive lines mix allusions to both natural and man-made features:

Five years have passed; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters, and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With sweet inland murmur. Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

Which on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard tufts,

Which, at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Among the woods and copses lose themselves,

Nor, with their green and simple hue, disturb

The wild green landscape. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild; these pastoral farms

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up in silence, from among the trees!

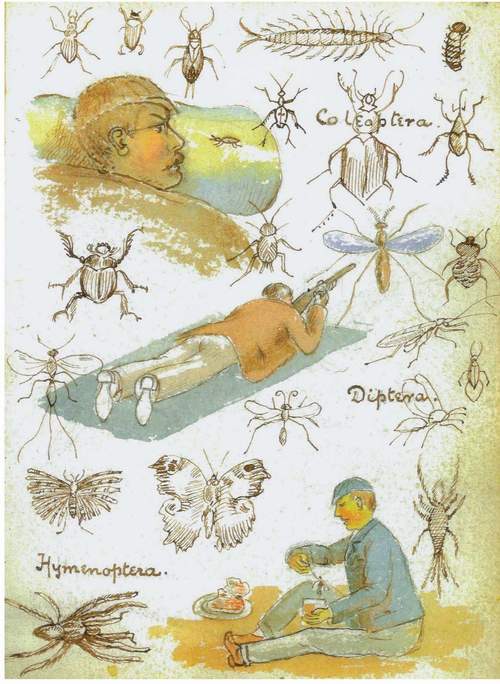

The Wye Tour faded with the coming of the railways in the 1860s, but it lingered in modified form well into the twentieth century. By the late nineteenth century visitors seemed more inclined to notice the wildlife. Thus, on a sunny, late-summer trip down the river below New Weir, a visitor noted ‘the flowers we could see on the banks, how they shone golden amongst the green! The gipsy gold of the tall clock sorrel still flourishing; the witch’s plant, the ragwort, the mouse-ear hawkweed, unfolding its golden fringes, and the yellow bedstraw shining in the sun; the golden flowers of the golden period of the year’ (Valentine, 1894). In 1892, ‘Four men in a boat’, rowing from Whitney to Chepstow, left a fine humorous sketch of insects in the Wye gorge between Lady Park Wood and Dowards (Fig. 9) (Baker, 2003).

Today, the view from the Eagle’s Nest still takes the breath away. Beyond the Lancaut peninsula and the woods on Piercefield Cliff, Chepstow Castle and the great Severn bridges stand out against the Severn estuary itself. The Devil’s Pulpit gives a pilot’s overview of Tintern Abbey to anyone prepared to walk a short distance over the wireworks bridge. Visitors who struggle up to the Kymin still stare for ages at the amazing panorama over Monmouth to the Black Mountains. The world-famous view from the Yat Rock, now the symbol of the Lower Wye, has, with the help of the Forestry Commission’s car park, a small tea room and the not inconsiderable attraction of peregrines nesting on Coldwell Rocks, become a magnet for visitors. From Coppet Hill the wide sweep from the Dowards round to Chase Wood gives distant views of the Welsh hills, Garway Hill and the Woolhope Dome. Further north, the Wye overviews are inevitably less spectacular, though the panoramas from Caplar and Ballingham hills are fine by any standards. And then there are the immense views from the Trellech plateau over the Usk, and from Garway over and beyond the Monnow.

Walkers and canoeists also know that these are just the highlights. Less famous are the views over Brockweir from Madgetts Hill; over Bigsweir from St Briavels, from Coxbury Lane towards Bigsweir Bridge, from Highbury Farm over Lower Redbrook, and from the recently opened Duchess Ride above Llandogo. Standing precariously on the Seven Sisters rocks, one feels the power of the conqueror viewing the Wye between Biblins and Wyastone from above.

FIG 9. A light-hearted memory of late nineteenth-century insect life during a trip down the Wye by four men in a boat. (Reproduced by permission of Michael Goffe, the son of one of the tourists)

From the river, the picturesque view of Goodrich Castle is still striking to modern canoeists, coming surprisingly after the subdued riverside scenery below Wilton. The view of Ruardean Church is probably best seen from the river, from where fleetingly the woods and river-bank trees provide a pair of tight side-screens, and the view of Coldwell Rocks is far more impressive from the river than from the land, but only for a hundred metres or so, while the high rocks loom over the river. Old photographs record other fine views that have been obscured by the general twentieth-century increase in the amount of woodland and the size of the trees, but the best are open and more will soon be revealed.

The picturesque appreciation of the landscape as a rugged and infinitely varied intermixture of the works of people and nature remains with us today. In a general sense it could apply to almost any tract of varied countryside, but the Lower Wye, in common with Coalbrookdale and the Severn Gorge, the valleys of the White Peak in Derbyshire, the Maentwrog valley in Snowdonia, and the Middle Clyde valley around Lanark, combine a distinctive mix of a confined, varied, semi-wild, well-wooded and well-populated ex-industrial landscape with the upland moors not far away. True, the landscape between Hereford and Ross is less spectacular – its rounded slopes interdigitate with the broad, meandering valley, and most of the ground is pastoral and beautiful, whereas the Wye gorge is rugged and picturesque (Whitehead, 2005) – but even here the woods bring shape and variety, and the steep wooded banks of Caplar Wood and Ballingham Hill lend a touch of drama.

SCIENTIFIC ENQUIRY

Unlike more celebrated places, such as the New Forest and the Lake District, the Lower Wye has been relatively neglected by modern field ecologists, so it may seem perverse to include scientific enquiry among the local themes. As a woodland ecologist working in the valley in 1970, I was acutely aware that I was promoting the ancient woods of the gorge as one of the most important concentrations of native woodland in Britain, yet there was no sign in the specialist ecological literature that they even existed, save for Eleanora Armitage’s descriptive paper in an early Journal of Ecology (Armitage, 1914). Even so, the district has long been studied by members of two early – and still thriving – clubs devoted to scientific enquiry into history and natural history in the field, namely the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club, based in Hereford, and the Cotteswold Naturalists’ Field Club, based in Gloucestershire.

The Woolhope Club took its name from the Woolhope Dome, a structure of great interest to early geologists (Morgan, 1954; Ross, 2000). It was founded in 1851 following a proposal by a local vicar, W. S. Symonds, to the Herefordshire Natural History, Philosophical, Antiquarian, and Literary Society, itself founded in 1836. The new element appears to have been field meetings, which in the early years involved stagecoaches and the like. Primarily a club of landowners, doctors, clergy and other professionals, it contributed substantial studies of local geology, fungi and other subjects, but became more orientated to archaeology in the twentieth century. It remained conservative in outlook, so much so that the centenary photograph shows a crowd of middle-aged and elderly men, one boy and no women, and the 17 chapters of the centenary book (Woolhope Club, 1954) were written by three reverends, one lord, one major, eight MAs, one MSc and one MD. Despite the contributions of Eleanora Armitage to the Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club (TWNFC), women were excluded from membership until 1954. By then, in 1951, the Herefordshire Botanical Club had broken away in frustration and thrived – with an understandable preponderance of women. In 2007 the Woolhope Club had 550 members; it continues to publish its Transactions, and was able to compile an impressive sesquicentennial collection (Whitehead and Eisel, 2000).

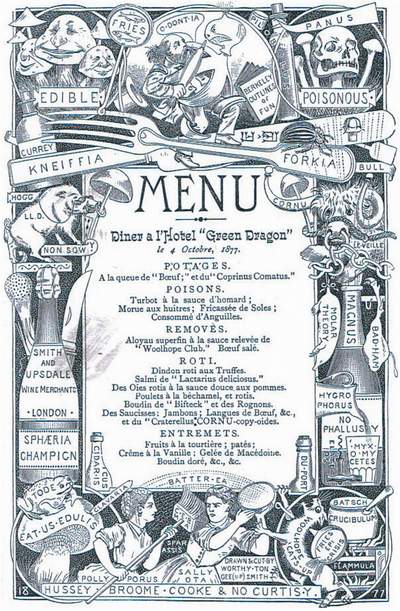

Perhaps the Woolhope Club’s greatest contribution to natural history consisted of the famous ‘forays amongst the funguses’ that were initiated in 1868, thereby coining a phrase that mycologists use to this day (TWNFC, 1868, pp 184-92). Members first explored Holme Lacy Park, but after ‘having sufficiently beaten the umbrageous preserves…and carried off piles of vegetable beef-steaks’ they moved on to ‘the hanging groves’ of Caplar Wood and then repaired to dinner. Their priority was clearly to find something to eat: in the previous year Dr Bull had published illustrations of edible fungi together with several recipes (TWNFC, 1867, pp 149-69), and the account of the 1868 foray ends with a detailed description of how each find was cooked for the evening dinner (Fig. 10). The Club’s forays eventually led to the formation of the British Mycological Society.

FIG 10 (opposite). Menu card for dinner following a fungus foray by the Woolhope Club in 1877. The accompanying page of explanations makes clear that every item is either an excruciating pun or an in-joke. For example, the dead mole to the right represents ‘the miserable condition of Mr Lees’ ‘molar theory’, which linked the formation of fairy rings to the ‘underground gyrations of the mole.’ At the bottom, Hussey, Broome, Cooke and Curtis were ‘renowned fungologists’: the fighting ladies above, Polyporus and Psalliota, refer to the fact that Hussey and Broome had fallen out. (From Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club)

The Cotteswold Naturalists’ Field Club pre-dated the Woolhope Club (Fletcher, 1946). The inaugural meeting on 7 July 1846 in the Black Swan, Birdlip, was followed by an excursion on 18 August to the Dean, where they walked to the Buckstone in a continuous downpour. Undaunted, several later excursions penetrated north of the Severn, often as joint meetings with the Woolhope, Malvern and other clubs, but their principal area of activity was on the south side of the Severn, as their name implies. Field excursions and winter meetings were notable for the size and duration of meals, just like those of the Woolhope Club, and no doubt that was the fashion of the times. Lady members were admitted in 1920, well before they were allowed into the Woolhope Club. The Cotteswold’s activities faded a good deal in the twentieth century, but it remains active, with 1,100 members, and has been publishing Transactions since 1847.

One of its specialist sections persevered with a plan to publish a county Flora. After a false start in 1853, compilation really started in 1877, was almost complete by the early 1920s, and was ready for publication in 1938, but war intervened and the first page proofs were not available until 1946. Understandably, by the time it was published in 1948, two of its three editors had been dead five years. Thankfully, the result, one of the most informative of all the county Floras, justified the effort (Riddelsdell et al., 1948).

The valley also starred in the formative years of the now powerful British Ecological Society. In July 1914 the first BES summer meeting took place at Ross at the instigation of Eleanora Armitage, assisted by H. H. Knight and welcomed by Henry Southall (Journal of Ecology, 2, pp 202-5). After Eleanora’s lantern slides of the Wye gorge, the first excursion took the ecologists to Symonds Yat, where they noted that these were the most westerly natural woods dominated by beech, and contrasted them with the Leigh Woods overlooking Bristol because, in the gorge, ash ‘takes a very secondary position’. They were also fascinated by the bog above the Dropping Wells. Next day their visit to Chase Wood was marred by heavy rain, but they noted many contrasts between the limestone and sandstone woods. Then, on the final day, they were again out of luck with their excursion to the Woolhope Dome: their ‘arrangements had unavoidably to be suddenly altered’, which restricted their visit to an examination of Blackberry Hill.

The earliest plant records appear to have been made by touring botanists. John Parkinson recorded opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage near Chepstow in 1640; John Ray recorded wood vetch and madder near Tintern in 1662; and the Reverend John Lightfoot recorded wild cabbage on Chepstow Castle and several rare species around the Castle Woods and Wyndcliffin 1733. The first published list of Herefordshire plants was produced by the Reverend John Duncumb in 1804. The principal figures in Herefordshire during the nineteenth century were the Reverend William Henry Purchas (1823-1903), Reverend Augustin Ley (1842-1911) and Dr Henry Bull (1818-85) (Lawley, 2001). Purchas, a bramble specialist, was born in Ross, but never worked in the county, yet he botanised on his visits and also found rare sedges on the Wyndcliff. Ley was effectively the leading county botanist from 1870 onwards, but also recorded down to Chepstow, and produced many early records of mosses and liverworts. Together with Purchas, he produced the first comprehensive Herefordshire Flora in 1889. Bull was a polymathic local doctor, one of the founders and sometime president of the Woolhope Club, a botanist, zoologist, historian, archaeologist, but especially also a mycologist and pomologist. At the suggestion of Edwin Lees (1800-87), a botanist based at Malvern, who also recorded many species in the Wye Valley, he started the Woolhope Club’s fungus forays in 1868.

There were many others, of course. Eleonora Armitage (1865-1961) was the daughter of a prominent county family and a founding member of the British Ecological Society, who was responsible for numerous bryophyte records. The Reverend Charles Binstead (1862-1941), sometime vicar of Mordiford, founder of the Moss Exchange Club and eventually President of the British Bryological Society, also contributed bryophyte records. Later, Lilian Whitehead (1894-1979), a leading member of the Herefordshire Botanical Society, produced a Handlist of the Herefordshire flora (Whitehead, 1976).

In Gloucestershire and Monmouthshire, the county Floras (Riddelsdell et al., 1948; Wade, 1970) demonstrate a quickening of the pace of recording during the nineteenth century. The pioneer of British fern culture, Edward Lowe (1825-1900), moved to Shirenewton Hall for his last 18 years because the district was rich in ferns, and Major Cowburn, another avid fern collector, lived at Boughspring, but there is no sign that they left important records. Indeed, one wonders if they contributed to the loss of rare species and unusual forms. Miss E. A. Ormerod (1828-1901, see below) compiled an early list of plants for Sedbury and Chepstow district. The Reverend E. S. Marshall (1858-1919), a botanist of the critical school, made many records from the Lower Wye. He came to live in Tidenham in 1919, intending to help production of the Flora, but died soon after. W. A. Shoolbred (1852-1928), a doctor who lived at Chepstow throughout his career, worked with Marshall, and produced his Flora of Chepstow. The Reverend H. J. Riddelsdell (1866-1941) worked in Aberdare, Llandaff and parishes in Oxfordshire, but he edited the Flora from 1908 onwards, and posthumously he is named as the first author. H. H. Knight (1862-1944) developed a critical knowledge of bryophytes in Gloucestershire, and S. G. Charles botanised in the Wye Valley after 1942, especially around Monmouth. For the last 50 years, Trevor Evans (Fig. 187), the spiritual descendant of Shoolbred, has lived in Chepstow and recorded the flora of Monmouthshire.

Zoologists have not apparently matched botanists, such as Eleanora Armitage and W. A. Shoolbred, in concentrating their efforts on the Lower Wye. Eleanor Ormerod, a pioneer researcher on insect pests, was brought up at Sedbury Park, but her career work was done elsewhere (Wallace, 1904). As a leading agriculturalist, she proposed the complete extermination of house sparrows (Lovegrove, 2007). Her enthusiasm seems to have been fixed when, on 12 March 1852, a rose-underwinged locust ‘appeared amongst’ a group who were changing horses while the coach waited outside the George Inn, Chepstow: they chased it half a mile down the street and captured it by the bridge. The salmon fisherman H. A. Gilbert (1928) concentrated on the Wye, but was more interested in the upper river. Many naturalists, such as the lepidopterists Neil Horton (1994) and Michael Harper (Harper & Simpson, 2001) and the general naturalist Colin Titcombe (1998), worked within particular counties. National experts, such as Keith Alexander, have surveyed sites within the Lower Wye as part of studies on a larger scale, and in the case of Moccas Park several have come together to study a particular site (Harding & Wall, 2000). Several research projects based in the area have been published, including Paul Bright’s study of dormice (Bright et al., 1994), Stephanie Tyler’s study of dippers (Tyler & Ormerod, 1994) and the wide-ranging survey of aquatic ecology by Edwards & Brooker (1982). Despite all these and others, the fauna of the Lower Wye is not well known.

The Lower Wye has thus been reasonably well endowed with naturalists, but few have concentrated on the valley. Indeed, the problem is that almost all worked on a county basis, and for them the Lower Wye was literally peripheral and just a small part of biologically exciting counties, saved from obscurity by the spectacular concentration of sites in the limestone parts of the gorge. The Gloucestershire portion has suffered particularly from county-based recording, cut off as it has been by the Severn from centres of population and the focus of natural history interest in the Avon Gorge. Furthermore, universities are far away, the valley has not been readily accessible from London, and the Wye Tour declined before recording got into its late-nineteenth-century stride. Apart perhaps from Shoolbred, few naturalists have regarded the Lower Wye as a unit.

One other, totally different, form of enquiry originated in the Lower Wye: the fascinating but controversial idea of ley lines. For this we are indebted to Alfred Watkins, born in 1855 into a family of south Herefordshire farmers, who worked as a brewer’s representative travelling round his home county, but who was also an inventive amateur photographer. One day about 1920 while riding over the hills near Bredwardine he had a flash of inspiration that the countryside was crisscrossed by a network of straight lines, or leys, defined by a mixture of natural features and prehistoric artefacts, such as mounds, old stones, moats, cairns, mountain peaks, notches on slopes and old churches, many of which had been founded on places of prehistoric significance. He interpreted these as the surviving signs of a network of tracks that had been laid down by prehistoric travellers while sighting the ‘lie of the land’ from elevated positions. Once established, he envisaged that junctions and alignments were marked by stones, trees, hollow ways, burial sites, encampments and other features. The idea was first presented to the Woolhope Club in 1922, then published as The Old Straight Track (Watkins, 1925). It even gave rise to the now-defunct Old Straight Track Club.

The evidence is unconvincingly anecdotal, but strangely attractive. It is certainly intriguing that the old churches of Woolhope, Holme Lacy and Aconbury align with the camp on Aconbury Hill at precisely its highest point on the western margin. This ley linked with another through the churches of Woolhope, Fownhope, Little Dewchurch and Much Birch. These and other leys were supposedly marked by stones placed along the route, for example where they crossed rivers. Distinctively shaped, unworked, but often small, these mark-stones also included conspicuous standing stones, such as the Queen Stone in the bend of the Wye at Symonds Yat and the Harold Stones at Trellech and Staunton. Mark-trees were also supposed to have been planted: in 1925 Watkins noted that many ley lines were marked by Scots pine, though it is difficult to see how introduced trees planted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries could have any bearing on prehistoric events. Few now believe in ley lines, though more would like to believe, and we have increasingly recognised that prehistoric people were more organised, and moved over greater distances, than we once thought.

ECOLOGICAL DIVERSITY

The rest of this book is concerned with the natural history and ecology of the Lower Wye and the interactions between people and the natural environment, but it is worth identifying themes here that will be expanded in later chapters. As we have seen, the Lower Wye has long been a borderland in historical and political terms, but it is every bit as much a borderland in biological and land-use terms, too. The region lies right on the boundary between highland and lowland Britain. To the west the land is hilly, the climate is oceanic, the rocks are mainly old, land use is predominantly pastoral and the assemblage of wild plants and animals includes numerous species whose main ranges are concentrated in northern and western Britain. To the east the landforms are more subdued, the climate is more continental, the geological substrate is relatively young, land use is predominantly arable and urban, and the centre of distribution of most wild species is to the south and east. Admittedly, almost any part of Britain contains species on the edge of their ranges, but in the Lower Wye the biogeographical and human gradients are steeper than in most other regions. Within a few kilometres, the Lower Wye links the low, uneventful landscape of the English Midlands and the high moorland promontories of the Brecon Beacons.

The landscape and land use of the southern Welsh borderland is noticeably diverse. The Wye gorge is almost a detached portion of the Dordogne region of central France, but parts of the adjacent Trellech plateau have something in common with the North York Moors. The Dean, too, is Continental in its high density of forested land, but southern Herefordshire, with its scatter of woods set in a matrix of farmland, is quintessentially lowland English. Within 4km we can travel from the wooded cliffs of the Wye gorge to the estuary of the Severn and the flat, unwooded, drained marshland of the Caldicot Level. Ecologically, too, there is great diversity: within the woods, for example, the soils range from some of the most alkaline in Britain to some of the most acid.

Much of the Lower Wye falls within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and indeed natural features, such as the riverside cliffs and the sweeping meanders of the river itself, come readily to mind when the district is mentioned. Nevertheless, it is quite clear that people have occupied and used the district since the last ice age, and that they were present well before that. No doubt that is true of most parts of Britain, but in the Lower Wye we have proof, notably in the remains that have emerged from caves and rock shelters in the gorge, and the astonishing footprints of Mesolithic families walking over the Severn estuary muds. Today, the Lower Wye is not densely settled by the standards of southern England and south Wales, but we have our quota of Roman settlements and Iron Age fortified hilltops to show that people have always been a significant part of the scene. Indeed, Roman ironworks and the remains of lapsed metalworking on some Wye tributaries remind us that the Lower Wye was an early industrial centre.

Nevertheless, despite the long presence of people as farmers, foresters and industrialists, natural features have survived on a substantial scale (Fig. 11), helped by patterns of land use that have remained fairly stable for millennia. Most obviously, the Lower Wye Valley retains its remarkable landforms and underlying geology, visibly shaped by the natural force of the river. Despite large quarries right by the tidal reaches, including one that continues to remove one of Gilpin’s ‘folds of the valley sides’, we still see river-cut cliffs emerging from

FIG 11. The scene looking downstream from one of the Seven Sisters. This is as near as one can approach a natural landscape in the Lower Wye. The foreground shows a small part of the scrub and rock garden, kept open by droughts on the top of the rock. Beyond is the mixture of beech, yew, large-leaved lime and whitebeams that occupies limestone outcrops and beech hangers on the Little Doward. Groups of planted conifers and, in the distance, the line of the A40 dual carriageway confirm the existence of people.

ancient woodlands at the Wyndcliff, Ban-y-Gor Rocks, the Seven Sisters, Coldwell Rocks and several others. Despite the mining in Clearwell Caves and archaeological excavations in King Arthur’s Cave, there are still extensive, almost pristine cave systems and complex overlapping underground streams in the limestone. The Wye has the reputation of being one of the most natural rivers in southern Britain, and can still flood the whole of the natural floodplain, to the great inconvenience of back-lane users.

Despite millennia of forest clearance, the Woolhope Dome and the gorge have always been well wooded, one of the few districts of Britain where the original forest cover has been punctuated, but not fragmented. Moreover, the ancient woods still have a strong representation of small-leaved and large-leaved limes, the tree species that dominated in the prehistoric forests of lowland England five thousand years ago. Presumably, also, the ground vegetation of these woods would be reasonably familar to a Mesolithic hunter, since it grows beneath near-natural mixtures of tree species on soils that have been little changed by people. The distribution of many woodland plant species must be much the same as it was in primeval woodland.

Given the survival of natural features on a grand scale, it is understandable that the Lower Wye gorge is perceived as a relatively natural region, and understandable that it should form the core of an AONB. The contrast when driving from the intensively worked farmlands of lowland England into the gorge is great. Even so, much of the perceived naturalness is reconstituted, in the sense that what we see now has reverted from a state of intense use, so the gorge probably looks more natural now that it has looked for a thousand years. This is particularly true of the Angiddy, Whitebrook and Redbrook, the main tributary streams running into the gorge, which conceal dams, pools and remains of furnaces among small fields and mature woodland. The sources of some of the ore, the scowles, are hidden in regrown woodland, dark, gloomy defiles, avoided by foresters. The railways came and went within a century, leaving tunnels to bats, cuttings to be recovered by woodland, causeways across the floodplain farmland, and sections of level track used as forest roads. The medieval weirs have also gone, marked now by short rapids. Commercial river traffic has ceased, allowing trees to grow on banks that were once used as towpaths and leaving the water to canoeists and kayakers seeking a wilderness experience. No longer coppiced, the ancient woods have grown taller than they have been for a millennium, and the charcoal hearths that produced the fuel for the forges lie concealed in the undergrowth.

If there has been one theme running throughout the Lower Wye, it is the long and more-or-less equal coexistence of people and nature. Despite continuing changes, we have maintained a balance: the district is neither natural nor artificial, but a mix of both. Historically, this balance was mediated through inhospitable soils, limitations placed on the land use and intensity of occupation by rugged landforms, the continuing influence of tides and natural hydrology, and the power of natural processes to reassert natural conditions once intense use has ceased. Today, despite the reserves and restraints of the conservation ethic, we deploy enough resources to wreck the place.

The Picturesque tourists’ happy co-acceptance of both natural and artificial elements in the landscape has been succeeded by two contrasting perceptions of the Lower Wye landscape. One, being conscious of the enduring, all-pervasive presence and impact of people, sees the landscape as man-made, leads to the acceptance and promotion of change, and would give freedom to landowners to do what they wish. The other, recognising the survival and reconstitution of natural features, perceives the landscape as natural, or nearly so, and this leads to resistance to change and antipathy to intensive and visible management. Given its designation as an AONB, the ‘natural’ perception restrains development, but it is applied more to the appearance of the landscape than its substance. We rely on land managers to maintain an illusion of naturalness where in fact there is careful control, and the specific efforts of residents and land managers together to maintain what is left of the Lower Wye’s natural form and biodiversity.