CHAPTER 3

Wye Valley Landscapes

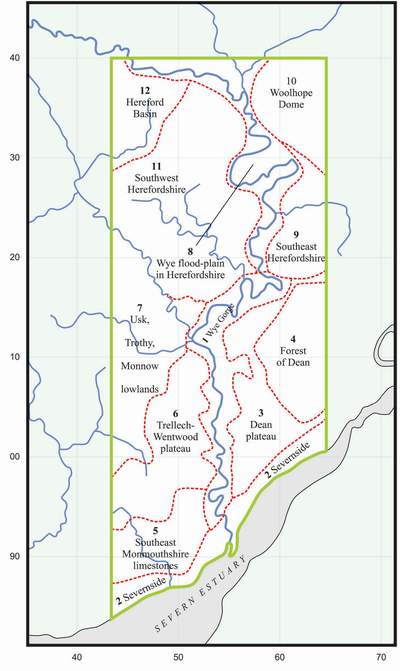

THE SOUTHERN WELSH borderland is a region of steep hills, rolling farmland, large woods and wide valleys, lying between the low and uneventful landscape of the English Midlands and the high moorland promontories of the Brecon Beacons. It is also a region of great diversity, defying generalisations. Within the Lower Wye and its surroundings we can usefully recognise at least twelve districts with more-or-less distinctive landscapes. Figure 32 shows their boundaries and how they relate to the rivers, the main settlements and the boundaries of the AONB. However, the districts are far from uniform within themselves and not as sharply defined as the map purports. Indeed, much of the charm of the region is its diversity, and the ability to be in one landscape while enjoying a clear view of another.

The key district is the gorge (district 1), which forms the spine from Goodrich to Chepstow, and separates the undulating uplands of Gloucestershire and Monmouthshire. To the south is the distinctive district of alluvial flats and gentle rises that borders the Severn (2). To the east is the Forest of Dean (4), and between the Dean and the gorge is an irregular limestone plateau of farmland and woodland that I will call the Dean plateau (3). To the west we find the high Trellech-Wentwood plateau (6) and the distinctive area of lower limestone hills in southeast Monmouthshire (5), which broadly correspond to the Dean and Dean plateau respectively. To the north and west of the Trellech plateau is the low-lying farmland of the Trothy, Monnow and Usk valleys, together with some well-wooded gentle hills to the west of Monmouth (7). In Herefordshire north of the gorge, the Wye floodplain (8) forms the spine, with the distinctive hills of the Woolhope Dome (10) to the northeast. The extensive rolling Old Red Sandstone countryside of southern Herefordshire is divided between a southeastern district

(9) that was once part of the Forest of Dean, and a southwestern district (11) that broadly corresponds with the ancient enclave of Archenfield. Finally, the low-lying plain to the southwest of Hereford (12) is treated as a separate district.

WOODLAND DISTRICTS

Four districts have above-average woodland cover, and all are relatively well endowed with other semi-natural habitats.

Wye gorge (District 1)

The gorge is the Lower Wye for many people. From Goodrich to Chepstow it forms an outstanding picturesque and sublime landscape, with interlocking spurs receding into the distance, the river and valley meadows framed by steep woods, rugged cliffs, wild hedges and a surprisingly high density of settlement. Where it cuts through limestone at Symonds Yat and below Tintern it forms a miniature counterpart of the Dordogne, but, with its long history of metalworking and other industries, its ecology and landscape history have more in common with the White Peak, the Middle Clyde, Coalbrookdale and Ironbridge. Tintern Abbey and its surroundings are a southern version of Rievaulx, both Cistercian foundations. The largest country house at Piercefield is a ruin, but Bigsweir House remains at the core of a long-established estate in the St Briavels meander, while Pilstone House and Wyastone Leys occupy enviably sunny positions, and Courtfield faces Lower Lydbrook at the head of the gorge. Aside from Tintern, the most recognisable building must be the tea house surmounting the Kymin.

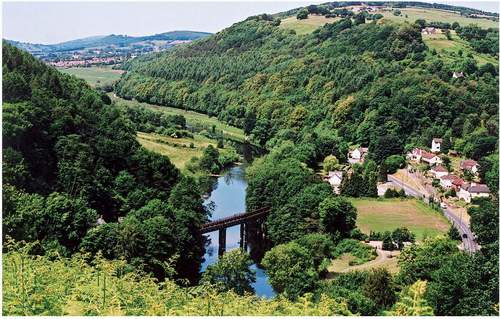

The famous view from Symonds Yat Rock (Fig. 1) symbolises the Lower Wye, but the view from Highbury Farm towards Monmouth is more representative (Fig. 33). Ancient woods hanging from the slopes do not quite reach the river, but leave a narrow, grassy floodplain. Redbrook reaches the river at the Millennium Green, built on poisonous spoil from the defunct metal industries. The derelict railway bridge is now a footpath. The foreground is steep pasture that is no longer used, whereas the plateau is well-cropped farmland where hedges are either overgrown or reduced to grassy baulks. In the distance beyond Wyesham, Buckholt Wood tops the hills.

The two towns occupy special positions. Chepstow developed 2km upstream from the mouth of the Wye, where ancient river crossings coincided with defensible positions, its ancient, walled core now encircled by housing estates and industrial enclaves. Monmouth grew where the Monnow and Trothy break

FIG 33. The view over Redbrook from Highbury Farm. This scene summarises the gorge far better than the view from Yat Rock.

into the gorge, the only point where low ground extends to the Wye (Fig. 34). Between them, Redbrook, Whitebrook, Llandogo, Brockweir, Chapel Hill and Tintern are straggling villages based around ports and early industry. Above Monmouth, Dixton stands on the floodplain and Hadnock remains a farmed enclave between the Wye and Highmeadow Woods (Fig. 35). Further up, Symonds Yat, Lower Lydbrook and Bishopswood have a considerable industrial past and, at Lydbrook, an industrial present. Throughout, settlements extend up tributary valleys and take the form of scattered houses, rising in tiers among the woods and small fields, most conspicuously at the Kymin, Symonds Yat West, Llandogo and Brockweir.

The outstanding habitats are the river, the inland cliffs, extensive ancient woodlands and a small-scale patchwork of tiny fields, walls and large hedges within which a moderate amount of semi-natural grassland survives. The most dramatic are the limestone cliffs, which gleam brightly among woodland from Coldwell Rocks to the Seven Sisters, and from Tintern to Chepstow. The famous King Arthur’s Cave, which is located high in the woods on the Doward, was the focus for early studies of prehistoric faunas, and these studies have extended to other caves and rock shelters nearby to produce a long and detailed environmental history. More recently, the Otter Hole, an extensive cave system that runs under Piercefield Park and St Arvans, has been discovered and explored. Most of

FIG 34. View over Monmouth from the Kymin to the Hendre Woods and on to the Blorenge, Sugar Loaf and Black Mountains, with St Mary’s Church, the Wye bridge and the A40 motorway in the centre of the picture, and the Monnow valley entering from the right. Two hundred years ago, Monmouth residents and Wye tourists walked from the town to the tea room on the Kymin to see one of the finest panoramas in southern Britain.

the Lower Wye’s Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are concentrated along the gorge.

The Wye itself is a ‘wild’ river. With both banks overhung by mature trees and kingfishers regularly flashing past, the Wye below Little Doward (Fig. 11) reminds one of an Amazon tributary. Mostly, however, it flows within a narrow floodplain, bordered by steep, muddy banks. Below Bigsweir it is tidal, so salt marsh species become progressively more abundant on the wide, fluted banks of alluvium, and at several points ancient woods overhang the tide: there can be few other places in Britain where small-leaved lime shades sea aster and common scurvygrass. Today, visitors canoe at Symonds Yat and row at Monmouth, but until the nineteenth century commercial cargoes moved up and down river between quays scattered along the banks. Water depth was once regulated by weirs, but these survive now only as riffles and boulders that stand out noisily at low flows and low tides.

The ancient woods form an almost unbroken chain along the steep sides from Kerne Bridge to Chepstow. They have long been regarded as the most important of the Lower Wye habitats. Indeed, after surveying them in 1970, I concluded that they ranked with the New Forest, Caledonian pinewoods, oceanic oakwoods and East Anglian coppices as one of the five most important woodland groups in Britain. Two groups have always stood out, the upper gorge woodlands up- and down-river from Symonds Yat and the Blackcliff-Wyndcliff-Pierce Woods with their Gloucestershire counterparts in the lower gorge: whatever aspect of natural history one studies, they rank at the top. The woods on the sandstone are less diverse, but the Hudnalls and Cadora Woods form outstanding examples of this type of wood, and Cleddon Shoots is a nationally important bryophyte site. Highbury and other woods around the Newland meander form rich mixtures on outposts of the limestone. It is easy to forget that the sandstone part of the gorge is also notable for alder woods, mostly small tracts within drier woodland, but also extensive examples along the Slade and Mork Brooks above Bigsweir.

Despite the prominence of limestone, there is disappointingly little good limestone grassland, except for the exceptional patches on the Seven Sisters and

FIG 35. Hadnock Farm, an ancient Welsh enclave to the east of the Wye, backed by the Highmeadow Woods. This is the view that southbound motorists on the A40 glimpse as they race down towards Monmouth. Intensively farmed, many mature trees nevertheless remain on field boundaries. Conifers have long been a feature of these woods, but the Forestry Commission aims to strike a balance between them and native broadleaved stands maintained on long rotations.

FIG36. The southern margin of the Hudnalls from Madgett Hill. The small-field landscape formed by late eighteenth-century squatters on a wooded common contrasts sharply with Honeyfields (left), which lay outside the common. Most of the houses on the common have since been considerably enlarged, but the fields largely remain as semi-natural grassland.

some other outcrops. Fragments survive below Tintern, on the Great Doward, and below the motorway embankment above Dixton. Moderately acid grassland, however, is still well represented in small and often steep fields, especially around Highbury Wood, St Briavels Common (Fig. 36), and the steep, narrow side-valleys from Penallt southwards. Insulated from modern farming, many of the small fields are now overgrown with rank grass and scrub. The floodplain and gentle lower slopes around Hadnock, Monmouth and Bigsweir are largely cultivated, but substantial vistas of alluvial grassland persist opposite Llandogo. Below Tintern, distinctive brackish grassland fringes the river.

Natural though it appears, the Wye gorge is not a tranquil place. The A466 road runs through much of its length, the Biblins campsite attracts crowds to what would otherwise be a remote corner, Symonds Yat is a tourist honeypot, and military aircraft use the valley for training. Below Tintern, however, the road leaves the valley bottom, the cliffs are high, and buildings are out of sight, so it is almost possible to perceive the landscape as pristine – but only until one notices that Pen Moel cliff was a great quarry (Fig. 144), now largely healed by recovering woodland. In contrast, the great scar of Tintern quarry still stands out in James Thorns, and the Livox quarry is still removing one of the Wye’s picturesque interlocking spurs.

Forest of Dean (District 4)

The Dean is one of the two great medieval royal forests surviving in Crown ownership, but unlike the New Forest, sheep, not ponies, roam its commons. It deserves its own book, but it comes so close to the Wye that it cannot be completely ignored here. A fine historical account was written by H. G. Nicholls (1858), the perpetual curate of Newland, the parish to which the whole of the former extra-parochial core of the Dean became attached, and in modern times Cyril Hart has published numerous works, including Royal Forest (1966), a detailed history of Dean forestry. The Dean once extended to the Wye, but today it is clearly separated by the farmland of the Dean plateau, except around Staunton and English Bicknor, where all three districts intermingle confusingly, and in the Highmeadow and Doward woods, where the Dean still comes down to the Wye.

Beechenhurst is now the principal visitor attraction, but Speech House and the surrounding ancient pasture woods (Fig. 37) form the historical core. Now a hotel, Speech House was once the administrative seat of the forest, and it still houses the Verderers’ Court. The surrounding grove of oak, beech, holly, birch

FIG 37. Wood-pasture of oak, beech and holly at Speech House, the only place where the Dean woodlands resemble the Ancient and Ornamental Woods of the New Forest.

and grassy glades is the principal remnant of what in the New Forest would be ‘Ancient and Ornamental Woodland’, great trees surviving from the seventeenth century or earlier, when the Dean was a great unenclosed mosaic of grazed woodland, open plains, heaths and mires. That landscape can still be seen in the New Forest, but in the Dean so much more land was enclosed for timber plantations that the open forest landscape was reduced to ribbons and fragments, though traditional enclaves survive at Ellwood. Uniquely, the Dean is subject to common rights to mine coal, and was once punctuated by slag heaps and laced with tramways and small railways, but it is now far less industrial than it was. The slag heaps have been landscaped, the railways are cycle tracks, and forest villages, such as Cinderford and Bream, are left with a straggle of utilitarian housing. Free mining is now almost extinct, but one mine operated recently at Bix Slade near the Cannop Valley, and the Forestry Commission still has a Deputy Gaveller.

The Dean is an unusually well-wooded district that stands out on any national map of forest. Following particularly heavy fellings in the seventeenth century, the forest was progressively enclosed and planted with oak. Conifers were introduced from the late eighteenth century onwards and recently made up almost half of the plantations, but many are to be replaced by broadleaves. Today, the Dean remains a patchwork of oak, beech and various conifers, almost all originating as even-aged plantations, relieved by fringes of self-sown birch, oak, holly and grassy glades. Sheep continue to ‘enjoy’ open pasturage, though most seem to dice with death on road verges, where, if they survive the traffic, they benefit from the higher fertility of grassland enriched by lime-rich dust. They were culled out in the foot-and-mouth epidemic of 2001, but after some controversy they were allowed to return.

Ecologically, the Dean is limited by the predominantly infertile soils, formed from Coal Measures, but it remains outstanding for fungi. It once supported a good deal of acid grassland and heathland, with localised mires, and tens of thousands of veteran trees, but these have largely been replaced by plantations. The mature oak woods often produce stupendous bluebell displays, and at Nagshead the RSPB reserve has long been a popular place to see and study pied flycatchers. Nearby, Cannop Ponds – impoundments made in the early nineteenth century – provide the main stretch of open water. Semi-natural grassland remains in a few of the small fields. On the whole, however, it is the fringes of the Dean that hold more natural diversity.

Woolhope Dome (District 10)

The Dome is clearly defined as a range of moderately steep hills that rise sharply from the floodplains of the Wye, Lugg and Frome and descend almost as sharply to the orchard and farming country around the Marcles. Fownhope, Mordiford, Dormington and Tarrington form a ring of villages on the fringes, leaving the core to Woolhope, Checkley, Sollers Hope and a scatter of large, well-hedged farms. The hills rise to over 260m at the back of Stoke Edith Park, but the steepest gradients are confined to the outer rim between Dormington and Fownhope. Backbury Hill and other vantage points provide great panoramas west to the Black Mountains.

The Victorian naturalists of Herefordshire were so keen to study the Dome’s geology that they named their society after its principal village. Geologically, there is still much of interest, from the great nineteenth-century landslip above Dormington and the stratification revealed by the Pentaloe Brook, to the many small quarries at which the various strata are exposed. Ecologically, the principal interest lies in the woods and semi-natural grassland, which are arranged in concentric layers in response to geology and landform (Fig. 38). At the core is the

FIG 38. Landscapes of the Woolhope Dome: Rudge End Farm from Common Hill. The great Haugh Wood is now a mixed plantation, with mature native broadleaves on the fringes. Limestone grassland in the foreground is maintained by Herefordshire Nature Trust. Mature boundary oak and ash remain frequent in the farmland of mixed arable and pasture.

huge Haugh Wood, which, being centred on sandstone but extending onto Woolhope limestone, includes both small Sphagnum mires and dry calcareous slopes: it was and remains outstanding for Lepidoptera. Broadmoor Common is a large meadow with patches of marsh immediately to the east, and to the north the extensive meadows of Joneshill Farm are now a Plantlife reserve. Bear’s, Timbridge and Woodshut woods across the Pentaloe Brook survive as semi-natural alder, sessile oak and lime woods.

The outer zone is an almost continuous belt of woods on steep ground formed from Ludlow Shales and Aymestry Limestone. The most extensive woodland covers the hinterland above Stoke Edith Park, but much of this is secondary. Small woods on Common Hill and at the Herefordshire Trust reserve of Lea and Pagets Wood remain semi-natural, but plantations occupy parts of the former Fownhope Park, an ancient wood overlooking the Wye. In fact, the sheer size of the woods on the Dome encouraged plantation forestry, so, despite extensive felling and restoration of broadleaves in Haugh Wood, there is still a substantial element of conifers in the landscape. Paradoxically, plantation forestry may have saved the butterflies by keeping the rides open, and now management is jointly planned by the Forestry Commission and Butterfly Conservation.

Common Hill is an intricate mixture of woods, houses, fields, orchards and abandoned quarries. The Herefordshire Trust not only maintains woods, but also keeps remnant limestone grasslands and old orchards free of scrub. Daffodil pastures survive at Woolhope Cockshoot and Winslow Mill, a fine meadow survives as Checkley Common, and fine wet grassland can still be seen near Wessington Court, but generally the farmland in the wide, sweeping valley that separates the outer circle from the core woodland is intensively used. It remains attractive, with many mature boundary trees, well-maintained hedges and alder-lined streams.

Trellech-Wentwood plateau (District 6)

The high ground to the west of the Lower Wye forms a narrow promontory to the north around Penallt that expands southwestwards along the Wentwood ridge almost to the Usk. It is bounded on the west by the Brownstone scarp, steep indented hills giving huge, sweeping views over the Trothy and Usk valleys to the Black Mountains, Sugar Loaf and Blorenge beyond Abergavenny (Fig. 34). To the east it drops sharply to the Wye gorge. Short streams that drain into the Usk have cut deep headwaters into the western scarp, and rather longer streams, such as the Angiddy and Cleddon Brook, rise in the core of the plateau and drain gently in wide valleys until they approach the gorge, whereupon they steepen into mountain torrents. To the south, the district is bounded by the ecologically distinct Carboniferous Limestone country. Geologically, much of the land is underlain by Devonian sandstones and brownstones on which moderately base-rich woods have developed, diversified on the higher ground by heathland formed on decaying Quartz Conglomerate.

Standing stones (Fig. 57) and the physical remains of the once-substantial town of Trellech clearly demonstrate the long influence of people on the landscape (Wimpenny, 2000). In the Middle Ages, Trellech and Llanishen formed a large clearing in a huge wood-pasture that stretched from Wentwood to Wyeswood and the outskirts of Penallt (Bradney, 1913; Courtney, 1983). This semi-wild landscape, which was every bit as extensive as the Dean, must have looked like a hybrid between the New Forest and the wooded pastures at the head of the Olchon Valley (Black Mountains). The western edge was rimmed by coppice woods and small fields along the Brownstone scarp.

This semi-wilderness has since almost vanished. The wood-pastures of Earlswood and Coed Llifos became farmland with scattered woods; Wentwood, Chepstow Park, Fedw and the wood-pastures near the Wye gorge between the Angiddy and Whitebrook became coppices; Wyeswood thinned out to heathland; and all parts were reduced by assarting to form groups of small fields. The woods, which mostly passed through the Beaufort estate into Crown ownership, were promoted to high forest, with beech and oak along the gorge and conifers elsewhere. As late as 1769, the Lordship of Trellech contained 3,073 acres (1,244ha) of common between Mitchel Troy, Penallt and Tintern, and Kilgwrrwg also had 147 acres (59ha) of common (Courtney, 1983). The Trellech heaths survived until enclosure in 1810, but they were planted in the nineteenth century, and by the 1970s the district formed a notable concentration of conifer plantations. Fragments of the heath survive as Cleddon Bog (Fig. 109), Whitelye, Kilgwrrwg, Bica and Gray Hill commons, but they are all being colonised by trees. Gray Hill Common is a revelation: standing on heathland beside the ancient stones near its summit, it affords spectacular views over the Severn from Slimbridge right down to Flat Holm and Steep Holm.

Outside the main woods, this is a district of mixed farmland in medium-sized, irregular fields, interspersed with small woods, which still has a reasonably high density of hedges and trees, and many of the streams flow in natural, somewhat incised channels, lined by alders and other trees. However, around Trellech, and especially in the wide sweeping valley east of Llanishen, more of the land is arable and the aspect is somewhat open and bleak. The principal ecological interest lies in the remaining heathland, flowery grassland and enclosed semi-natural woods. The woods form a diverse mixture from the extremely base-poor sessile oakwoods on Parkhouse Rocks to base-rich mixed coppices on the scarp at Croes Robert Wood, which the Gwent Wildlife Trust maintains as a coppice with associated charcoal production, and the adjacent marsh woodland at Wetmeadow Wood. The semi-natural grasslands survive in small fields and large lawns: individually and collectively, they are attractive and diverse mixtures, ranging from the spectacular Gwent Trust reserves at Springdale Farm, New Grove and Pentwyn Farm, to Ida Dunn’s lawn in The Narth.

THE LOW GROUND

We now turn to three low-lying districts. None is absolutely flat. Even Severnside has some low, gentle hills; the Wye floodplain in Herefordshire is bounded by steep, wooded ground; and the Hereford basin rises gently out of a broad valley. However, all have very little woodland and once had extensive marshes and wet grassland.

Severnside (District 2)

The band of ‘reclaimed’ alluvium, punctuated by small outcrops of Carboniferous and Liassic limestone, that separates the Severn estuary from the ‘uplands’, is nowhere more than 6km wide. From the great motorway bridges, the Gwent or Caldicot Levels seem to be featureless flats, obliterated in part by a container park near Chepstow and the steelworks at Llanwerne, but ecologically they form the most distinctive part of our region. Upriver Severnside is a narrow belt of gravel and alluvium that expands within the great Severn bend at Awre.

This was a world of marshes and creeks. Drained long ago to create a landscape of ditches (reens) and fields (Fig. 39), protected by a sea wall, ancient villages occupy slightly elevated ground. Tiny ports once thrived where rivers and pills reached the Severn; the intertidal mud banks partially conceal the remains from a long history of occupation, fishing and transport by boat; and the Levels are now famous among archaeologists for the wealth of evidence they have yielded about long-term environmental history (see Chapter 4). Caldicot Castle, the Bishop’s Palace at Mathern and ancient churches remind us of enduring settlements and productive farmland (Rippon, 1996). Railways, motorways and power lines cross the Levels; Chepstow recently supported a major naval boatyard; Sudbrook has developed an industrial area; and pressures for further industrial development intensify.

FIG 39. Traditional landscape in the Gwent Levels: a reen near Magor Marsh. The cattle pasture to the left has recently been acquired as an extension to the Gwent Wildlife Trust reserve.

Until recently most of the land was used as permanent pasture for cattle and sheep, with some arable and meadow, and scattered withybeds and willow trees along the reens, but ploughland has latterly expanded. The back fens have largely been drained, but the Gwent Wildlife Trust has saved the best remnant at Magor Marsh (Fig. 107). The reens have collectively been recognised as a nationally important wetland, with a wealth of rare and local plant and invertebrate species, but their biodiversity has been substantially impaired by algal growth, feeding on wastes draining from farmland and the expanding villages. The sea walls and their associated maritime grassland support several plant species not found elsewhere in the region. The once-extensive salt marshes are now squeezed between the sea wall and the eroding intertidal mud banks, but small examples remain at Portskewett, and extensive grazed saltings remain undisturbed below Sedbury Cliff. Beachley Point even has fragments of shingle habitats. West of Goldcliff the Newport Wetlands reserve has recently been created on drained alluvium in compensation for the impoundment of Cardiff Bay.

Severnside also includes several outcrops of bedrock, the outliers of the uplands to the north, some of which are themselves important habitats. The eroding faces of Sedbury Cliffs (Fig. 105) support locally unique mixtures of woodland, scrub and flush-line fens, all overlooking salt marshes, and the Sedbury farmland has a few ancient woods and herb-rich pastures. The Beachley peninsula at the mouth of the Wye is largely built up, but the shoreline still yields some uncommon species. The islands of hard rock within the marshes, such as Portskewett, Sudbrook and Goldcliff, have either been built over or treated as intensive farmland, but until recently patches of rich limestone grassland survived.

Wye floodplain in Herefordshire (District 8)

The Wye enters our region west of Hereford and flows within a wide floodplain as far as Goodrich. There the floodplain narrows abruptly as it enters the gorge, but expands again briefly within the great loop around Huntsham Hill. This is a district of long, broad vistas over flat farmland, flanked by low hills (Figs 2 & 19). Where the Wye cuts close to the surrounding Old Red Sandstone uplands at Ballingham and How Caple, the slopes are steep and well wooded, a fine scenic counterpoint to the valley bottom. At several points, notably around Rotherwas, Holme Lacy and Walford, sand and gravel deposited at earlier stages in the Wye’s evolution form terraces which merge with the gentlest slopes on the sandstone. The riverside alluvium is rarely more than 600m wide, but at the confluence with the Lugg around Hampton Bishop it expands to 3km. The low promontories of Kings Caple and Foy, formed within two great meanders, are so remote from the uplands that, scenically and historically, they are almost part of the floodplain.

Older generations had the sense not to build on the floodplain: two ancient settlements, Hampton Bishop and Holme Lacy, occupy slightly elevated ground that affords some protection from floods. Elsewhere, the settlements that used the floodplain stand on the margins, including the attractive Hoarwithy with its Italianate church, the remote and mysterious settlements at Sellack and Foy, and Ross – where the spire and town rising on a low sandstone cliffbeyond a loop of the floodplain provide one of the great vistas of the Wye (Fig. 40). This is mostly a quiet and peaceful land, where the quacks of mallards on the Wye seem loud, but around Rotherwas Hereford’s industry and suburbs have engulfed the low terraces.

Until recently the entire floodplain was permanent grassland, much of which was treated as Lammas meadows (see Chapter 6). Aylesmarsh, Coughton and other marshes occupied shallow overflow channels, back channels, remote from the main channel, and peripheral depressions. However, most of the common meadows have been replaced by ditched fields, the marshes were drained in the nineteenth century, much of the valley grassland has lately been ploughed, and polytunnel fruit-growing has expanded around Ross.

FIG40. Ross-on-Wye on its sandstone cliff, as seen from the motorway. This view across the floodplain meadows ranks with the view from Symonds Yat (Fig. 1) and the view of Chepstow Castle (Fig. 60) as the characteristic image of the Lower Wye Valley.

Today, the principal ecological interests lie in the Wye itself (Figs 2, 19, 126, 127) and the surviving common grasslands. Near Hampton Bishop and Lugwardine the Herefordshire Nature Trust maintains fine examples of common meadowland (Figs 102, 103, 186), and at Coughton they protect a wooded remnant of the marsh. Common pastures survive at Backney and Sellack. Otherwise we are left with an ecologically impaired rural idyll.

Hereford basin (District 12)

Southwest of Hereford is a low-lying plain, underlain by sands, gravels and clays deposited by glaciers and alluvium washed down by the Worm and Cage brooks that was once part of the pre-Conquest Forest of Haye. The core is a broad valley around the headwaters of the Worm Brook, where extensive marshes and wet grassland once so excited Victorian botanists. The Allensmore and Tram Inn marshes have long since been converted to arable and sown grassland, leaving an open, flat landscape, drained by deep, steep-sided, algae-filled ditches, relieved only by a scatter of trees and shrubs on boundaries and watercourses that would make visitors from the Lincolnshire inmarsh feel at home (Fig. 41). Just a trace of

FIG 41. The Allensmore brook, one of the headwaters of the Worm Brook, near the Tram Inn. The stream is now a ditch draining arable plains, but in the mid nineteenth century this was a rich marshland that attracted the Victorian botanists.

this marshland remains as the Big Bogs, a swampy mixture of outgrown alder-oak coppice, ancient tree willows, pollards and a few old oaks.

Elsewhere, the district is mostly flat and arable, with well-trimmed hedges and scattered old boundary trees. The narrow Cage Brook valley, which is deeply incised into the plain, has fine floodplain alder woods near Clehonger, and dense, hanging, oak-dominated, ash-hazel-wych-elm woods below Clehonger that link to the steep, wooded slopes above the Wye. Even in the rugged country around Rudhall, grassland has either been improved or allowed to develop into scrub, and much the same fate has overtaken the scatter of commons. Arkestone Common is divided between mature woodland and arable crops; Littlemarsh Common has been neglected for several decades, but still retains tracts of herb-rich marsh at its core; and Honeymoor Common is still an extensive wet grassland embellished with tree-fringed ponds, though it has been under-used lately. On the southern margins the ancient Treville Forest occupies gentle Old Red Sandstone hills: it is still very well wooded, and until 1991 it contained the tallest oak in Britain, a sessile oak that rose to 41m.

THE LIMESTONE DISTRICTS

The limestone that is so conspicuous in parts of the gorge underlies both the plateau that separates the gorge from the Dean and the low hills that separate the Trellech plateau from the Caldicot Level.

Dean plateau (District 3)

Open farmland extends from east of Ruardean in an irregular arc past Coleford to the fringes of Severnside at Alvington, Aylburton and Chepstow. One is always aware of the valleys, for magnificent panoramas extend from Poors Allotment over the Severn, and around Hewelsfield, St Briavels and Ruardean over the Wye. To the south the plateau divides around a bowl of farmland at Woolaston, formed where erosion of the Clanna pericline has exposed Old Red Sandstone. Here, the deep valleys that collect around Rodmore Mill have produced one of the most diverse and secluded spots in the Lower Wye, an amalgam of woods, steep fields, marshes and lakes that contrasts totally with the nearby plateau. Political links with the Dean have always been strong, for St Briavels Castle was once the seat of the constable of the Dean, Newland was the ecclesiastical focus, and Coleford has become the de facto capital. The southern portion was long ago separated as Tidenham Chase, a region of large woods and open heaths, and the rest was alienated from the Dean in the Middle Ages.

Much of the plateau consists of large fields used either as arable (Fig. 95) or as leys for sheep and cattle. Trimmed hedges and dry-stone walls form the field boundaries, with a thin scatter of ash trees. A few well-hedged green lanes and minor roads with undisturbed verges provide some diversity. Settlement seems sparse, but most of the villages are either tucked away on the margins or, like Clearwell, hidden in valleys. Fine farmhouses and cottages built from limestone give a hint of the Craven landscape in Yorkshire. Hewelsfield Church, standing with its ancient yew in a circular churchyard, must be an early foundation.

The limestone plateau is pockmarked with unexpected depressions, and streams tend to disappear underground and emerge elsewhere. One particularly strong emerging stream gives its name to Clearwell. The intermittent streams, solution hollows, the tufa formations, caves and the mined iron-bearing deposits known as scowles are all features of karst, already described in Chapter 2. At Whitecliff, near Coleford, the remains of the eighteenth-century iron furnace remind us of the Industrial Revolution. Abandoned quarries can be found by many lanes and in most woods, but these have been succeeded by super-quarries at Stowe Green, Scowles and Whitecliff.

The plateau fringes contrast strongly with the wide, open plateau. Many groups of tiny fields have been produced by squatters settling on the Hudnalls and other commons, the edge of the open forest ‘waste’ and the steep slopes southwards from Clanna. Some of these, such as as Coalway, Broadwell and Christchurch, have now become extensive, amorphous suburbs, and Berry Hill completely spans the plateau from the Dean proper to Highmeadow Woods. Most of the woods sit in this boundary zone. To the west they run directly into the gorge woodlands, but ancient woods are also clustered in Tidenham Chase, around the Clanna pericline (Fig. 42), on the Dean fringes at Noxon and Lambsquay Woods, and between Newland and Staunton. Most are well-drained limestone woods, but some around Tidenham and Staunton grow on sandstone and Quartz Conglomerate, and these are almost heathy. Some woods on the edges of the limestone, such as those around Clanna Mill, are astonishingly wet, and there is even a small, wet alder wood on the St Briavels part of the plateau.

Semi-natural grassland is now confined to the small fields associated with the former commons and the wooded slopes on the fringes, especially in the intricate landscape along the slopes from Woolaston Woodside to Boughspring and Woodcroft. The Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust reserve at Ridley Bottom

FIG 42. Woolaston Slade, part of an intricate tract of ancient woods, secluded small fields, overgrown hedges and narrow lanes on the edge of the Dean plateau. The tall small-leaved limes in the hedges and woods demonstrate that the fields were carved directly from ancient woods.

and the floriferous lawn and pasture at Ashberry House are particularly rich. Heathland is found on strongly acid soils over Lower Drybrook Sandstone on the plateau at Poors Allotment near Tidenham and over Quartz Conglomerate at Staunton Meend, and there are also fragments in the commons along the Dean margins at Sling and elsewhere. Woolaston Common is unfortunately not grazed and has now become a bracken thicket.

Southeast Monmouthshire limestones (District 5)

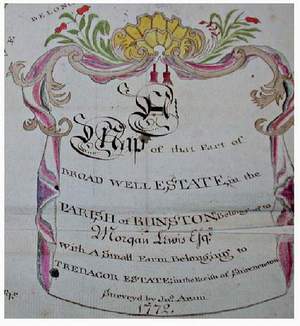

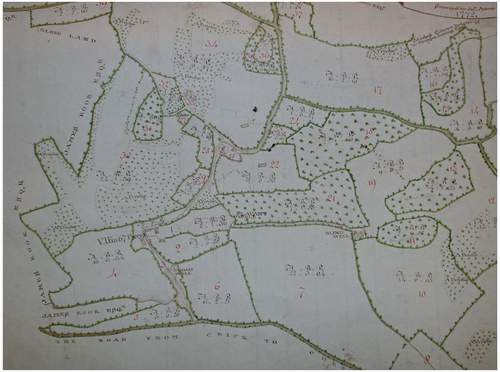

This tract of low hills running west from Chepstow and St Arvans to Magor, Llanvaches and Penhow includes the Roman town of Caerwent and the nearby Silurian hill fort of Llanmelin. When Morgan Lewis’s huge St Pierre estate was mapped by John Aram in 1772-88 (Fig. 43), the low hills were a patchwork of numerous small and large coppice woods, linked by tree-lined hedges and extensive ‘brakes’ (secondary scrub woodland) in a matrix of mainly arable fields with some pasture and meadows beside the rivers. Some woods and many field boundaries have since been removed, but until the 1940s the district remained notable for both substantial areas of limestone grassland and large ancient coppice woods, notably St Pierre’s Great Wood, the woods around Mounton, the Minnets and the woods around The Cwm and St Brides Netherwent. Sadly, post-war forestry changed the Minnets and almost all the woods near Chepstow into plantations; the farmland has become arable, leys and improved pasture; great quarries have been developed at Penhow, Rogiet and Caerwent; and houses have spread along the M48 around Chepstow, Caldicot, Portskewett, Rogiet and Magor. Only older residents of Chepstow will remember that the Bulwark estates were built on limestone grassland full of bee orchids.

Salisbury Wood and the Cwm woods are still fine semi-natural mixtures of beech, lime, ash and others, though archaeologists destroyed the fine stands on Llanmelin hill fort 30 years ago. Remnants of limestone grassland survive within the fences of RAF Caerwent and at Brockwells Farm: the latter’s wildlife was recorded by the owner-naturalist, Colin Titcombe (1998), and is now a Gwent Wildlife Trust reserve. The verges in the Minnets plantations are kept open and remain floristically rich (Fig. 149). The upper Mounton Brook flows through fine alder woodland and extensive semi-natural pastures, and small parts of St Pierre’s Great Wood and the woods around Mounton remain semi-natural. In fact, above and below Mounton we have a miniature Wye Valley. A small river flows through a narrow floodplain hemmed in by steep banks exposing limestone cliffs, all clothed in ancient woodland. The valley bottom is occupied by pasture, still semi-natural, but not particularly rich, and the stream meanders among alders. Unlike the Wye Valley, the Mounton Woods have all been

FIG 43. Part of Runston, as mapped by John Aram for Morgan Lewis of St Peer [sic] in 1772 (Gwent County Record Office D501.1332 f3). This is an unplanned landscape that evolved by progressive clearance of woodland to leave sinuous hedges containing a high density of hedge trees. The intermixing of wooded and unwooded ground has been reinforced by the development of ‘brakes’ over parts of the fields.

replanted, leaving only fragments of semi-natural woodland, and in dry periods the river issues from four springs at Wellhead and disappears into the ground again before it reaches Mounton.

THE DEVONIAN FARMLANDS

These extensive districts can easily be dismissed as ‘ordinary farmland’, but that would be unfair. True, a high proportion of the land is arable, leys and improved grassland, the districts tend to be geologically uniform and semi-natural habitats are thinner on the ground than elsewhere, but, with localised exceptions, such as the Hope Mansel valley, they still have many well-trimmed hedges, a good scatter of boundary trees, including some large pollard oaks, and many natural-looking streams, so by the standards of commercial farmland they remain diverse and attractive.

Lowlands of the Usk, Trothy and Monnow valleys (District 7)

This district between the Trellech plateau and the Monmouthshire county boundary extends down to the Wye at the confluences near Monmouth (Fig. 34). These are wide valleys and gentle hills, rising to rather steeper wooded hills between the Trothy and Monnow at The Hendre, on the wooded ridge north of Monmouth, and on the slopes above Michel Troy leading up to the Trellech plateau. The district, like the A40 trunk road, passes seamlessly through to the broad Usk valley, but there is a natural limit where the valleys reach the deposits of the Usk glacier on a line between Raglan and Llantilio Crossenny. The narrow lanes and quiet fields around Llangattock and Newcastle remain astonishingly remote.

This is a world of scattered settlements and small villages, such as Dingestow, secluded by tall hedges, deep, narrow, winding lanes and many farmland trees in a gently undulating pastoral landscape. Ecologically it is rather uniform, for almost the whole district is underlain by Old Red Sandstone, but limestone bands and base-poor sandstone layers have produced a range of moderately alkaline to strongly acid soils, with the result that small patches of heath and lime-rich flush woodlands can both be found within the Hendre woods. Most of the large woods were converted from coppice to plantations in the twentieth century, but thick hedges and long, narrow alder corridors along tributaries maintain a diverse and predominantly deciduous appearance. Until the 1930s, semi-natural pastures, meadows and marshy patches along the streams were common. Now, very few semi-natural grasslands remain, so the rides in the plantations have become relatively rich herbaceous habitats by default. The rivers and headwaters, however, continue to flow in natural courses with narrow floodplains.

Southwest Herefordshire (District 11)

The boundary between this district and the last follows the county boundary along the Monnow, turns up the Worm Brook valley and on to Dinedor Camp and Rotherwas Park, from which it overlooks Hereford. The eastern boundary is the Wye floodplain. Geologically, southwest Herefordshire comprises large tracts of the Brownstones of the Old Red Sandstone, dissected by the valleys

FIG 44. Autumn tints in oaks near the Brownstone escarpment southwest of Orcop Hill. Few parts of the Old Red Sandstone country have a density of boundary trees to match this.

of the Gamber, Garren and other Wye tributaries. To the west, the Brownstone scarp forms a series of rounded hills at Garway, Orcop (Fig. 44) and Aconbury that afford spectacular panoramas of the Black Mountains.

Historically, most of this is Archenfield, once a semi-autonomous Welsh enclave in England. Some parts fell within medieval forests, and these still have substantial woodlands: the northwestern parts were once part of the Forest of Haye, and the core contained Aconbury and Harewood Forests, which have left us with Nether, Wallbrook and Athelstans woods. Hidden among the lanes are gems such as the churches at Kilpeck and Garway, the former with its green man and elaborate corbels, the latter with its detached, circular tower, once a refuge for the Knights Templar.

This is rolling farmland, diversified by winding lanes leading to secluded villages, where long views are interrupted by hedges and boundary trees. The farmland, however, is almost wholly arable or sown grassland with little ecological interest, relieved only by a scatter of woods, sunken lanes on slopes, small fields around villages, a few flower-rich verges (Fig. 152) and the network of generally well-maintained hedges. Ash and oak are well distributed in boundaries, but they are rarely abundant and few ancient pollards remain. The hedges bear the signs of eutrophication and early woodland clearance, for they have few primroses, anemones and dog’s mercury, but abundant nettles.

The woods are large, ecologically uniform and not well known. The most interesting is evidently the ancient deer park at Kentchurch Court (Fig. 45). The semi-natural elements outside the woods also seem to be very limited now, though the nineteenth-century botanists were able to find several interesting species around places like Orcop and St Weonards. Today, one would expect to find a few fields of semi-natural grassland along the line of hills and on the flanks of the Wye and Monnow valleys, but surveys in the 1970s revealed that little remained, even in the small patches of small-field landscapes around Kings Thorn and Little Birch. The principal remnants of semi-natural vegetation cluster on hills and slopes, such as Coles Tump, a gorse-studded sheep pasture near Orcop, and some of the slopes above the Wye. The largest tract is Garway Hill Common, an outlier of Welsh hill grass and bracken. More interesting is the common in Garway village, an oasis of semi-natural grassland, heather and

FIG 45. Kentchurch Court from Garway Hill, surrounded by the plantations and pasture woodlands of Kentchurch Park. The ground under the ancient oaks, maples, yews and chestnuts is a mosaic of bracken, marsh and dry grassland with patches of meadow saffron. Together with the contiguous Garway Hill Common, this is the most extensive survival of semi-natural grassland in southwest Herefordshire. Jack o’ Kent’s oak (Chapter 5) is hidden behind the plantations in the right foreground. The distance shows a sample of the farmland of southwest Herefordshire, predominantly arable and sown grassland with a fair density of boundary trees.

small acid mires, maintained – where it is not a playing field – as a meadow with scattered ancient trees, with a central area of pits and pools surrounded by scrub woodland.

Southeast Herefordshire (District 9)

Finally, we have the district east of the Wye between the Woolhope Dome and the northern extremities of the Wye gorge, the Dean and the Dean plateau. To the north of Ross the district is essentially a low-lying extension of Devonian farmland, which interdigitates with the Wye floodplain. To the south the prominent wooded hills of Penyard Park, Chase Wood (Fig. 46) and Howle Hill – outliers of the Tintern Sandstone, Coal Measures and Carboniferous Limestone – that dominate the valley were once part of the Forest of Dean. Not far to the east are the extensive woods around Dymock, with their famous displays of wild daffodils, and the wooded hills of the Lea Bailey and Wigpool Common.

In the past, semi-natural woodland and grassland were extensive, acid mires were found on Howle Hill, and marshes spread over the Coughton Valley and the low ground towards the Wye. Today, the woods are still there, with fine old

FIG 46. Kerne Bridge from Coppet Hill, with the plantations of Chase Wood in the distance, the small-field landscape of Leys Hill to the right, and the villages of Walford and Coughton on the fringes of the floodplain. Small willow-covered islands have formed downstream of the bridge.

beech and oak stands on the strongly acid soils of the Tintern Sandstone around Howle Hill contrasting with mixed ash hangers above the Wye and around the rim of the Hope Mansell valley, but the farmland is intensively cultivated. Well-trimmed hedges and fine spreading oaks are still common around Yatton and there is a good deal of ‘improved’ grass in the district as a whole, but the Hope Mansell and Coughton valleys comprise mainly arable and sown grass with few hedges and farmland trees, leaving only fragments of semi-natural grassland in small fields on the upper slopes and evocative names, such as Pontshill Marsh and Meadow Farm, on the map. Likewise, most of the larger woods have been converted to plantation forestry.

Some semi-natural grassland remains in the small-field landscape behind Howle Hill, and remnants of heaths and bogs can be found on Wigpool Common and Mitcheldean Meend. The shaded Quartz Conglomerate cliffs within Chase Wood and Penyard Park still have some rare ferns and bryophytes. The woods north of Ross have limited interest, but the steep wooded slopes above the Wye at Caplar Camp and Lyndor Wood remain partly semi-natural and still support some of the interest that was explored by the Victorian naturalists.

LAND TYPES

Landscape descriptions inevitably emphasise the woods and steep hillsides, which stand out in any view of the district, so one can easily believe that they occupy a high proportion of the area. In the present context, they also dwell disproportionately on the semi-natural habitats that interest naturalists. In sober reality, however, most of the land is gently undulating farmland, and this needs to be quantified if we want to understand the true character of the Lower Wye habitats and consider landscape-scale conservation issues (see Chapters 8 and 11).

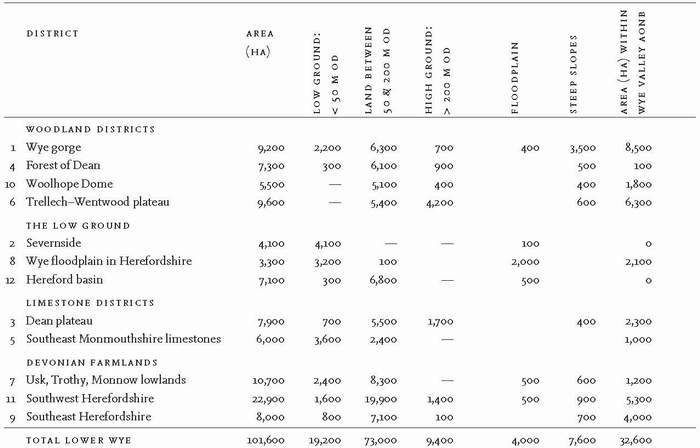

Quantification is surprisingly easy. By taking 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey maps and using the 1km intersections of the national grid as sample points, we can count the ‘land types’ that coincide with each intersection. Since each ‘hit’ represents an area of 100ha, a land type that coincides with, say, eight intersections covers about 800 ha. This procedure has been followed for a boxed rectangle surrounding the AONB, bounded by the 44 grid line to the west, 64 to the east, 85 to the south and 40 to the north. Excluding points that fall in the Severn estuary, this gives 1,016 intersections, i.e. it assesses a total area of 101,600 ha. Within this, the AONB contains 326 intersections, which fractionally under-represents the actual area of 32,816ha.

First, some details about landform (Table 2). The Lower Wye ranges from sea level up to 366m on Garway Hill. Most of the land lies at moderate altitudes between 50m and 200m above sea level, but 18.9% lies below 50m, and 9.3% reaches above 200m. Although the highest land is in southwest Herefordshire, the high ground is concentrated on the Trellech and Dean plateaus and adjacent parts of the gorge and Forest of Dean. The whole of Severnside lies below 50m, and the only point where the Wye floodplain stands above 50m is to the west of Hereford. Floodplains (defined as land close to the rivers that did not have a contour line between the intersection and the river, i.e. less than 5m above the river) occupy just 3.9% of the land, mostly along the Wye, but also along the larger tributaries. Steep ground, defined as land where the contour lines were less than 1mm apart (i.e. a gradient of at least 20%), occupies just 7.5% of the land area, a surprisingly small proportion in a conspicuously hilly region.

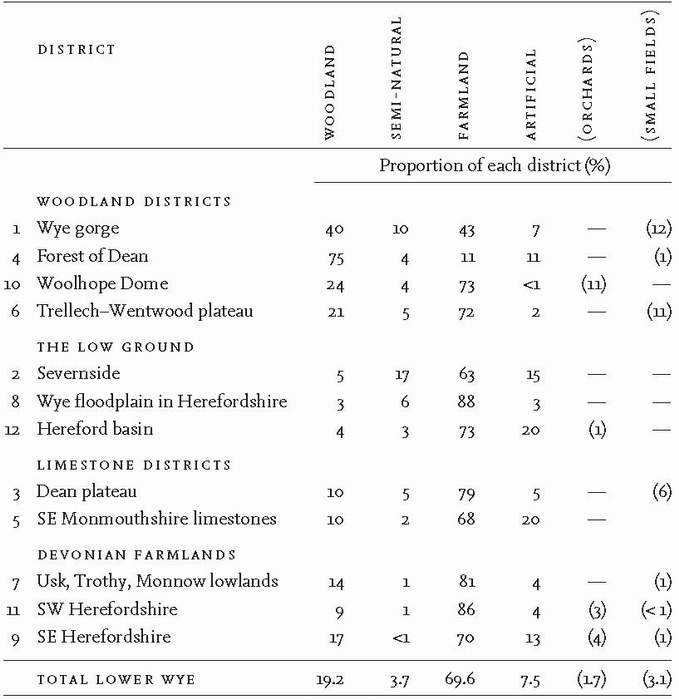

Four main land types are recognised (Table 3). ‘Woodland’ is the land coloured green on the Ordnance Survey maps. Artificial habitats include urban land, houses and their immediate plots (usually gardens), industrial estates, roads, railways and quarries. Semi-natural land types are those non-woodland habitats specifically identified on the maps, such as scrub, marsh, salt marsh, rivers and pools. Farmland is the rest, i.e. the ‘white’ land on the map, together with parkland and orchards. Two distinctive Wye Valley components of farmland have been separately identified: orchards and the groups of tiny enclosures formed when squatters colonised commons (see Chapter 4).

The results confirm very clearly that even in and around the Lower Wye the great majority (70%) of the land is farmland. Woodland covers just over 19%, and the balance is made up of artificial land types, mainly residential, and semi-natural land types outside woodland. Residential and developed land may seem obtrusive, but the urban districts cover just 4.1%, even though much of Hereford City comes within the survey area; rural houses and their gardens cover 1.5%; roads, tracks and railways cover 1.8%; and quarries just 0.1% of the Lower Wye. The river that gives the district its focus occupies just 0.8%.

The table also shows how much the various districts vary among themselves. The Wye gorge and Forest of Dean stand out as the districts where woodland and semi-natural vegetation together exceed the area of farmland. These, the Woolhope Dome and the Trellech-Wentwood plateau are the districts with above-average woodland cover. Semi-natural habitats are widely but thinly scattered, but are best represented in the gorge and by the salt marshes of Severnside, and poorly represented in the ‘Devonian farmlands’. Urban and residential land is understandably significant in the districts containing Hereford and Ross, but Monmouth ‘vanishes’ and the impacts of urbanisation

TABLE 2. Landforms and the distribution of high and low ground within each district in the Lower Wye.

around Chepstow and the line of dormitory villages along the M4/M48 come as a surprise. Farmland is particularly dominant in the lowland districts of the Usk-Trothy-Monnow, the Herefordshire Wye and the Hereford basin. It is also above average in the southwest Herefordshire district that links them, and on the Dean plateau. Some distinctive features of individual districts also emerge, such as the orchards of Herefordshire and the clusters of small fields in and around the Wye gorge and the Dean fringes.

Naturalists will focus their attention on the semi-natural habitats. Sadly, such habitats are poorly discriminated on Ordnance Survey maps, and, being rare, the grid intersection method gives only rough estimates of their extent.

TABLE 3. The proportion of each district that is occupied by each of the main land types. The values for orchards and small-field landscapes are included in the farmland values.

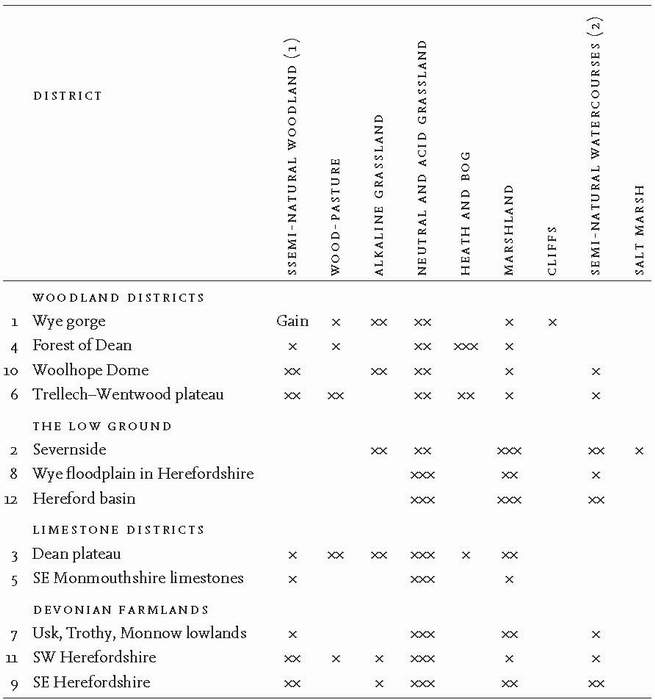

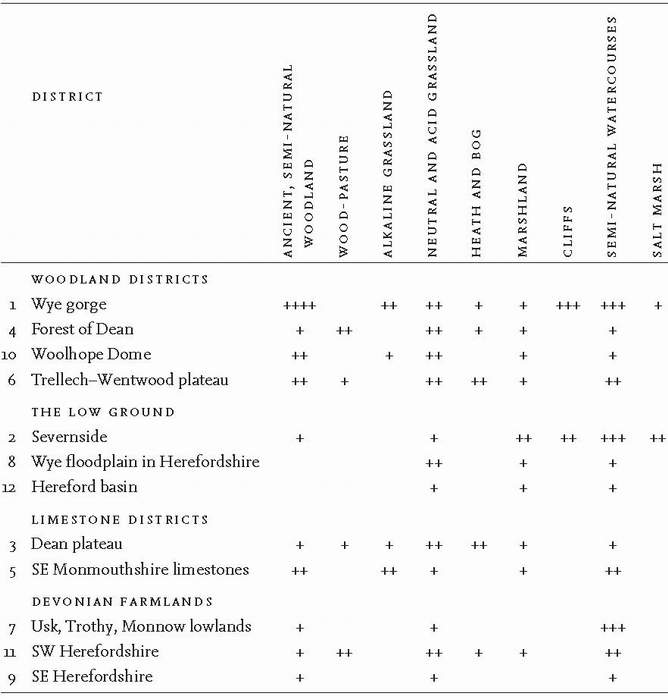

However, the conservation agencies and Wildlife Trusts carried out general habitat surveys in the 1970s and 1980s, and still maintain a watching brief on changes, so limited quantification is possible: details are given in Chapters 5 to 8. Here I give only a broad indication of the frequency of the main semi-natural habitats in each district (Table 4) and an estimate of how they have changed.

TABLE 4. The main semi-natural habitats within each landscape district.

++++ Very extensive habitat, including many important sites

+++ Extensive habitat, including important examples

++ Important example(s) present

+ Small amounts of habitat with no important examples

TABLE 5. Losses of semi-natural habitats in each landscape district within the last 200 years.

x Small proportion of total habitat lost

xx Moderate proportion lost, or most of a habitat of limited extent

xxx Most of an extensive or moderately extensive habitat lost

(1) Semi-natural woodland includes both ancient and recent secondary woods.

(2) Semi-natural watercourses are relatively unpolluted rivers and streams in a relatively natural bed. Relatively unpolluted ancient ditches are also included.

over the last 200 years (Table 5). The latter has been judged from old maps, pre-twentieth-century records of native plants, and my interpretation of land-use changes on the ground. With the sole exception of semi-natural woodland in the gorge, I judge all semi-natural habitats to have declined or remained more or less constant in all districts. Semi-natural grassland, heath and marsh have declined substantially wherever they occurred, and watercourses have been canalised or polluted in some farming districts. The greatest diversity of remaining habitats is in the gorge, and the most extensive and widespread key habitat is ancient, semi-natural woodland.