CHAPTER 4

Evolution of the Lower Wye Landscape

THE LANDSCAPE OF the Lower Wye has evolved over thousands of years from woodland into the intricate pattern of fields, woods, villages and roads we see today. Initially, the vegetation and fauna adjusted naturally to the climatic changes that followed the retreat of the glaciers, but from about 5,000 years ago the predominant force has been us and our predecessors. Today, the shape of the land remains much as nature left it, and most of the wild species arrived here naturally, but the pattern of vegetation has been largely determined by people. In fact, landscape historians often describe the landscape as a palimpsest, a metaphorical parchment on which successive patterns have been drawn, each modifying the earlier patterns, but never quite obliterating them. As writers like W. G. Hoskins (1956) and Oliver Rackham (1986) have shown, the landscape can be read as history: features made several hundred or a few thousand years ago have survived into the modern landscape as obscure mounds, banks and ditches, inconvenient road alignments and field configurations, ancient trees with strange shapes, quaint place names and many other forms.

This chapter traces how people have used and modified the Lower Wye. After reconstructing the primeval environment before human influence became overwhelming, it traces the history of human occupation and use, thereby enabling us to identify what is, or was, ‘natural’, assess stability and change, and dispel any notion that the borderlands have only recently been claimed from the wild. It will also provide some background to the habitats described in later chapters, and enable us to appreciate how wild species have adjusted to an increasingly people-dominated landscape. We will also recognise that the landscape has never been stable, a point that has implications for the conservation policies and practices considered in the final chapter.

The challenge is to link the original, natural landscape to the landscape of the last millennium. The main features of the former can be deduced from clues left in mires, caves, alluvium and marine deposits, and these reveal a predominantly wooded environment. The latter can be reconstructed in some detail from written records, old maps and archaeological remains, and these show that many features in the modern landscape were already in place at least by the twelfth century, often known by names we recognise on the modern Ordnance Survey maps. Between these two eras a great transformation took place, and our task here is to outline how, where and when it happened.

Most landscape historians understandably devote most space to recent times, but here the emphasis is on prehistory, when so much of the transformation took place. Historical and prehistorical detail has been summarised in several books on the borderlands in general (Sylvester, 1969; Millward & Robinson, 1978; Rowley, 1986, 2001), Gwent (Aldhouse-Green & Howell, 2004), Dean (Walters, 1992) and individual parishes, notably in the Dean (Herbert, 1996), Walford and Bishopswood (Morgan & Vine, 2002) and Dore Abbey (Shoesmith & Richardson, 1997). Finberg’s (1955) history of the Gloucestershire landscape inadvertently demonstrates how remote the Lower Wye seems from Gloucester.

Environmental archaeologists express dates either as years BC/AD or as years before the present (BP), the ‘present’ being fixed at 1950. They date objects and events by dendrochronology, radiocarbon isotope decay and comparison with dated sequences elsewhere, but only the first is precise and absolute. Fortunately, knowing how the amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere has varied over time, carbon dates can be recalibrated as absolute time, but, even after such standardisation, the classic divisions of prehistoric time shade into one another. In an attempt to simplify the complexities, I have rendered dates into calibrated BC/AD, except for the oldest periods, which are expressed as they were originally published, but as ‘years ago’ rather than years BP.

PRE-NEOLITHIC: THE ORIGINAL ENVIRONMENT

Stone hand-axes found in the Severn gravels at Sedbury and Sudbrook confirm that Neanderthals were present 200,000 years ago (Aldhouse-Green, 2004). They died out about 30,000 years ago, when anatomically modern humans replaced them. The last glaciation ended about 10,000 years ago, which is a realistic point from which to trace the origins of the modern landscape.

Pollen deposits throughout southern Britain show the widespread transformation from tundra through grassland and scrub to birch-hazel

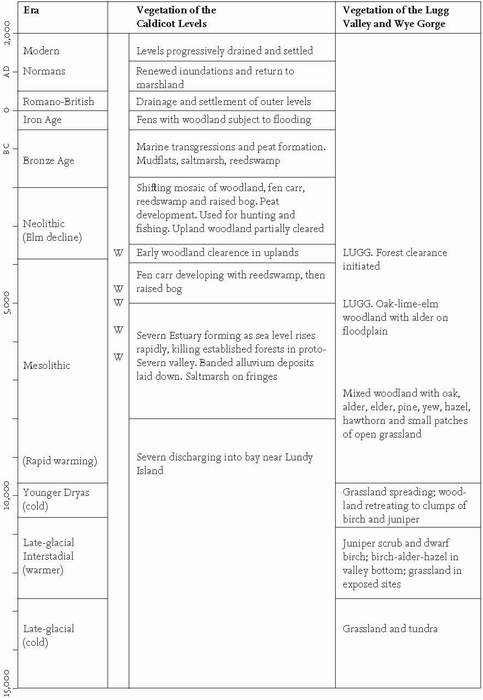

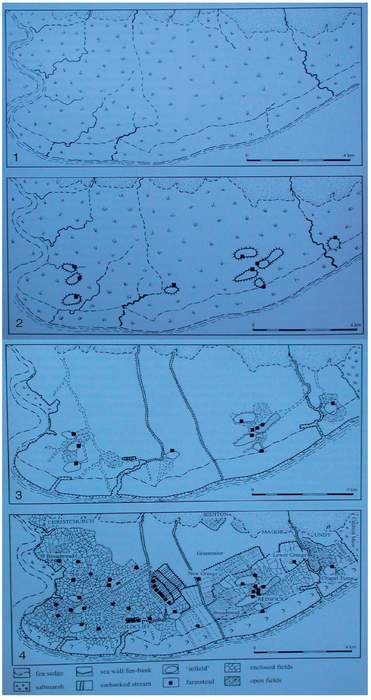

FIG 47. Time line and principal changes in habitats in the Wye gorge, the lower Lugg valley and beside the Severn from the late Pleistocene to the present. W shows the ages of buried forests exposed on the Severn margins.

woodland, and thence to pine and oak, and eventually to mixtures of oak, elm, lime and other deciduous trees (Godwin, 1975). By the early Neolithic, most of lowland Britain was covered by mixed deciduous forest dominated by lime (Birks et al., 1975; Greig, 1982). This broad sequence has been confirmed locally from pollen and plant macrofossils preserved in the peat of Caldicot Level and the Lugg floodplain. Furthermore, stratified deposits of various kinds in the caves in the Carboniferous Limestone and the alluvium and peat of the Caldicot Level have yielded astonishing details of ancient environments. The summary of changes in vegetation (Fig. 47) shows just how much happened before written records illuminate some of the fine detail.

Prehistoric fauna and people in the Wye gorge

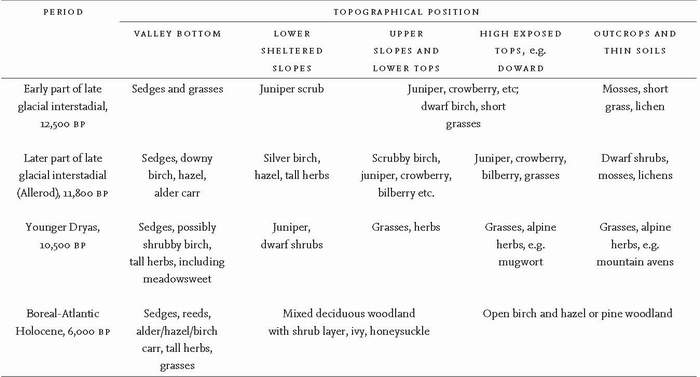

King Arthur’s Cave on the Doward (Fig. 48) has long been famous as the place where hugely exciting remains of Palaeolithic people were found in association with the bones of large, extinct mammals. Sadly, the deposits were not initially recorded by modern methods, and in any case miners exploring for iron ore dug there first. Moreover, much of the material may already have been removed: when the president of the Worcester Naturalist Society visited the excavation, he was told that ‘an immense quantity of bones had been got out of the cave, and

FIG 48. King Arthur’s Cave, the scene of much hunting in the Palaeolithic and archaeological explorations in the later nineteenth century. The visiting grandsons may inadvertently be re-enacting a Palaeolithic scene.

the tenant, a Scotch farmer, said he had for some time manured his fields with the bones of extinct animals which ages ago ranged over his holding’ (Clark, c.1875). A similar fate befell several human jaw bones in Merlin’s Cave, which were removed by boys searching for jackdaw nests (Bate, 1901). When it was first examined, small mammal bones were found on every ledge and in every crevice of Merlin’s Cave. Since then, most of the floor deposits have been excavated by archaeologists.

In 1870-72, the first investigator of King Arthur’s Cave, the Reverend W. S. Symonds, found the bones of a spectacular array of large mammals that collectively evoke images of a cold version of east African savannas, a far cry indeed from the modern Lower Wye (Table 6). The oldest deposits dated from the mid-Devensian glacial, about 39,000 years ago, when conditions were dry and vegetation was open enough to allow soil to wash down into the cave. Marks on the bones suggested that the cave had been used as a den by hyenas, but humans visited towards the end of the Palaeolithic (Symonds, 1871; ApSimon, 2003). Other caves, including the cave by the Longstone, the Slaughter cave system at English Bicknor, and a cave exposed by Caerwent Quarry (Titcombe, 1998) (Fig. 49), yielded similar assemblages, and the last also contained piles of

FIG 49. Remains of the Lower Wye’s ancestral fauna, found in a cave that was breached by a quarry near Caerwent. To the left is a woolly rhinoceros tooth, to the right a mammoth molar. The hands belong to Colin Titcombe, who found these and many other bones while he was working in the quarry.

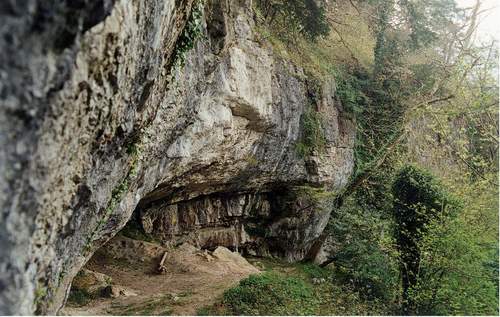

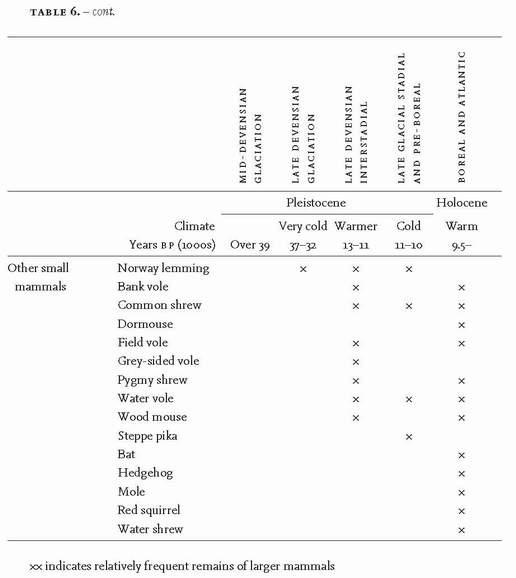

xx indicates relatively frequent remains of larger mammals

hyena coprolites, a sure sign of occupation. Later investigators no doubt hoped to find prehistoric paintings, like those in France and Spain, and etchings were actually claimed in a cave near Symonds Yat (Rogers et al., 1981). The claim was rapidly discounted, but, following the recent discoveries in Derbyshire, we await new searches with interest.

The next layers were deposited in the late glacial, 12,500-10,400 years ago. By this time the ground must have been well vegetated, for there was no sign of wind-blown soil. The main species in the deposits were red deer, wild horse and several small, subarctic mammals. The cave was clearly used by Palaeolithic hunting parties, for human bones were found with fire sites and chopped bones. The kills must have been made nearby, for the carcases were large – certainly the dry, narrow valley just outside the cave, which runs down to a cliff, would have been ideal for ambushes – but the main joints were taken elsewhere, and the hunters ate only limited quantities of meat and bone marrow there and then. Later, about 6300 BC, Mesolithic people butchered red deer, pigs, cattle, a few sheep, roe deer and horses in the cave, and, about 2300 BC, Beaker people lit fires. Significantly, no soil was washed into the cave at this time, suggesting that the slopes above the cave were wooded, and had neither been cleared nor cultivated.

The bones of small mammals were noticed in the earlier excavators (Hinton, 1925; Taylor, 1927), but they were not fully analysed until Nick Barton (Barton et al., 1997) and Catherine Price (2003) carried out a detailed analysis in several caves and rock shelters. Microscopic examination of each item enabled the species to be identified (Table 7) and suggested that most were deposited in owl pellets and carnivore faeces, while associated artefacts and organic remains allowed some of the deposits to be dated. Moreover, after allowing for the diet, habits and hunting range of the predators, inferences could be drawn from frequency of each species in each layer about the character of prehistoric vegetation, thereby showing how the tundra developed into the modern environment (Table 7).

The oldest deposits, found by the entrance to King Arthur’s Cave, dated from the cool, dry climate of the glacial maximum and slightly warmer interludes, possibly up to 25,000 years ago. The cave was surrounded by grassland, possibly with patches of open woodland during the warmer interludes. The remaining mammoths, woolly rhinoceros and hyenas lived with a variety of smaller species that now inhabit Scandinavia, the Siberian tundra and the Scottish Highlands, notably mountain hare, collared lemming, Norway lemming, narrow-skulled vole and northern vole. On the basis of modern habits and habitats, Catherine Price thought that the remains were deposited by roosting snowy owls, and that the fauna represented its regular diet.

The end of the glaciation was marked by a period of quite severe climatic oscillations. About 12,500 years ago (‘late-glacial interstadial’), the tundra species were joined by water vole, common shrew, field vole, pygmy shrew and species normally associated with woodland, such as bank vole and wood mouse. In addition, the remains of grey-sided vole were found for the first time in Britain. This was a period when juniper scrub and dwarf birch scrub invaded the slopes, leaving areas of grassland on the more exposed positions. Later,

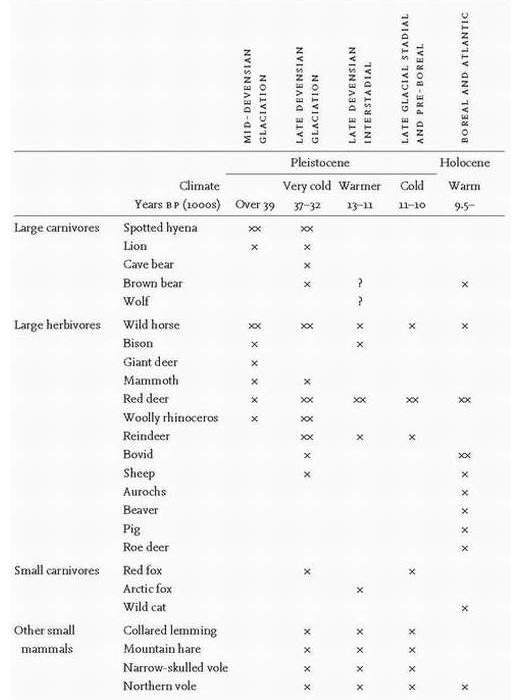

TABLE 7. The vegetation of the Wye gorge in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, as inferred from charcoal and the remains of small mammals in several caves. (Source: Price, 2003)

birch, hazel and alder woodland colonised the valley bottom and lower slopes.

Then, about 10,500 years ago, the cold conditions returned. Grassland spread, the juniper was pushed back to the lower slopes, but some birch and tall herb vegetation evidently survived along the valley bottom. Alpine herbs such as Norwegian mugwort and mountain avens may have colonised the thin soils of the exposed upper slopes. Deposits in Merlin’s Cave show that many of the non-tundra mammals retreated, though common shrew and water vole persisted. At this time the steppe pika, a relative of hares that survives now only in central Asia, colonised several areas in southwest Britain, including the Wye gorge. In one cave, the same deposits yielded the jaw of a bear. Since snowy owls avoid caves, it seems more likely that eagle owls were taking their prey into Merlin’s Cave.

This cold snap came to an end about 9600 BC with rapid rises in temperature that quickly established an essentially temperate climate. The colonists of the late glacial interstadial reappeared, though they seem to have been slow to react, possibly because a few centuries of warming were needed before the necessary woodland habitats could spread from their refuges to the Wye Valley. However, deposits in the Madawg rock shelter (Fig. 50) showed that by about 7000 BC the cold-climate species had died out, though northern voles lingered, presumably in nearby remnant grassy patches, and the fauna was essentially the familiar modern mixture of temperate species. New arrivals in this period were red squirrel, water shrew, mole, hedgehog and bats.

The latest deposits were found in the higher layers outside King Arthur’s Cave, against the walls of Merlin’s Cave, and under the Madawg rock shelter. These appeared to cover a range of periods from up to 6700 BC until the Bronze Age, but they all indicated a predominantly wooded environment in a temperate climate. The most abundant species were bank vole and wood mouse, but red squirrel, dormouse, common shrew, harvest mouse, mole, weasel and stoat were also present. Grassland voles had completely vanished from some deposits. The presence of harvest mice may appear to suggest some cultivated ground, but in fact this species is equally at home in reedbeds, which would have been present on the lower ground by the river. Interestingly, Rowena Gale (personal communication) found hazel and pine charcoal in the shelter, with some ash, oak, elder, yew, hawthorn and blackthorn, which hints that mixed deciduous oak-ash-hazel woodland had developed on the deeper, moister soils, and that yew and pine formed mixed coniferous scrub on dry sites and limestone crags, as they still do in northern Britain.

FIG 50. Madawg rock shelter, in dense woodland overlooking the Wye gorge, with excavation remains. This was one of several prehistoric occupation sites from which the small mammal populations of various eras were reconstructed from buried bone fragments.

Caldicot Level and its inhabitants

During the last 25 years an immense amount has been learned about the environmental history of the Caldicot Level. We owe this initially to a series of astonishing discoveries by Derek Upton, who worked at Llanwern steelworks, but spent his spare time exploring the estuary (Bell, 2005). Bones of prehistoric animals and trunks of ancient trees had been found in the nineteenth century higher up the estuary at Sharpness (Lucy, 1877), but Derek found so much more that he eventually persuaded archaeologists that the levels were of supreme interest. Today, a substantial programme of environmental archaeology at Reading, Lampeter and Exeter universities is advancing our understanding of early environments and how people used them (Rippon, 1996; Bell, 2001).

In 8000 BC the Severn flowed through a wide valley into a bay near Lundy Island, and by 6300 BC oak-hazel woodland had developed on the alluvium. However, about 5800 BC rising sea levels inundated the forest and enabled salt marshes to spread. When the sea level stabilised about 3950 BC, reed swamp spread over the marshes. This in turn developed into an ever-changing mosaic of carr woodland, moist woodland with large trees, raised bogs, pools and remaining reed swamp, which was periodically inundated by the sea. Marine incursions spread far over the marshes during the later Bronze Age and Iron Age, c.1200-200 BC, but by Roman and medieval times they were limited by sea walls. Today, wave action peels away the accumulated layers (Fig. 16) to reveal peat layers, tree trunks, ancient leaves, the bones and footprints of deer (Fig. 51) and primitive cattle (Fig. 52), the footprints of wild birds and, most remarkably of all, the footprints of Mesolithic and later people, impressed into the mud as they walked out onto the salt marsh.

Remains of the early estuarine forest can be seen over many kilometres at Goldcliff, Redwick and Gravel Banks (Bell et al., 2001). It lasted for several hundreds of years, during which oak was a major element. Individual trees lived for up to 400 years, many achieved diameters of 0.5-1.3m, and some had at least 12-15m of clean trunk. Higher up the Severn at Sharpness, tree remains in peat deposits formed in the bed of an old river channel comprised mainly oak, alder, beech and hazel (Lucy, 1877). Some oaks were huge: one was 24m tall, with a diameter of 85cm at the top and 1.5m at the base. When old land surfaces were removed, investigators found signs of the forests’ inhabitants – footprints of red deer and a larger footprint that may have been left by an aurochs. Charcoal layers showed that the forest was occasionally swept by fire, possibly started by people.

As the forest was inundated, dead and dying trees must have protruded gauntly from developing salt marsh for a century or more (Bell, 2004). Thereafter,

FIG 51. Imprint of a Mesolithic red deer in the sediments at Goldcliff.

FIG 52. This sculpture by Phil Bews of Coleford stands outside Taurus Crafts near Lydney. It is not an aurochs, but it magnificently evokes the beasts that once roamed the Severnside marshes.

on the evidence from peat to the east of Goldcliff Point (Smith & Morgan, 1989), common reed spread across the salt marsh and later developed through willow scrub into alder carr. These alder woods lasted for 600 years, so must have been self-regenerating, but about 5000 BC they gave way successively to reed swamp, shallow-water swamp dominated by great fen-sedge, then fen grassland. After 4600 BC, the grassland started to change into ombrotrophic mire, and eventually developed into a raised bog with Sphagnum mosses, bog-rosemary and various heathers that lasted until 1700 BC, when a marine incursion covered the bog in the estuarine sediments from which its remains are only now being exposed by coastal erosion. At Uskmouth, a slightly different succession took place between 5240 and 4940 BC: reed swamp developed through alder and birch carr to raised bog (Bell & Neumann, 1997).

These and other organic remains not only tell us about vegetation on the shoreline and wetlands, but also provide hints about the ‘dryland’ environment to the north of the levels and on islands within the marshes (Caseldine, 2000). Pollen and other plant remains associated with a Mesolithic site of 5400 BC near Goldcliff island indicated the presence of salt marsh by the shore, limited amounts of alder carr in the marsh, and oak-elm-lime-ash-hazel woodland on drier ground. Seeds of elder and the remains of three-nerved sandwort and hedge woundwort were also found, hinting that the woodland was similar to the ancient woods we can see today on the Carboniferous Limestone. Bracken spores were common, which may indicate burning, and hazel, with a good deal of oak, elm and a hawthorn-like wood, was found as charcoal. However, from 4800 to 4450 BC, as common reed and bur-reed spread over the surrounding marshes and patches of birch developed into alder carr, the dryland was occupied by elm-hazel woodland. The scarcity of lime suggested that the woods had formerly been cleared, but hazelnuts found at occupation sites bearing the teeth marks of bank voles, wood mice and dormice indicated a fauna like that of ancient coppices today.

Numerous tree stumps remain embedded in the mud at Goldcliff(Fig. 53), Redwick, Woolaston and elsewhere with prostrate trunks that had clearly been blown over by high winds (Allen, 1992). Dating from 5000 to 600 BC, they were the remains of moist, closed-canopy oak, alder, birch and willow woodland that was battered by storms from the south and west (most trees had fallen towards an arc from NNW clockwise to SSE). Most were slender, small-crowned trees, many of which had regenerated on fallen trunks, and which were mostly healthy when they fell. The woods may well have incurred repeated blowdowns, for they contained a good deal of fallen wood and they grew as groves interspersed with open fen carr and reed swamp.

Three profiles studied by Alex Brown (Brown et al., 2005) along a transect across the Severn shoreline at Woolaston Pill (Fig. 54) gave a clear indication of the main vegetation types present about 5725-3656 BC. Sea level fluctuated throughout this time to allow advances and retreats of marshland and intermittent peat development, as well as marine incursions, with consequential changes in the pattern of salt marsh, open fen of common reed, common club-rush or unbranched bur-reed, and carr woodland dominated by alder, but wet enough to support marsh fern, meadowsweet and mint. Interestingly, there was also a considerable influx of pollen from ‘dryland’ woodland, which suggested that the hinterland was a mixed woodland dominated by lime, oak, elm and hazel, with a limited admixture of birch, ash, pine and holly. Significantly, small amounts of hornbeam and beech pollen were also present, supporting the view that both species are locally native. This mixed deciduous, lime-rich woodland must have been very similar in composition to modern ancient woods in the Lower Wye, except that ash has partly replaced wych elm and Scots pine is now dismissed as an introduction (Peterken, 2005a).

People also lived in these woods and marshes. The earliest evidence of their presence was found at Goldcliff, in the form of flints, bone, wooden tools,

FIG 53. Prehistoric oak buried in the sediments at Goldcliff. This is a tree that has clearly grown as part of a dense stand. The cut shows where environmental archaeologists took a sample to determine the age and growth conditions of the tree.

FIG 54. An ancient oak being disinterred from the sediments at Woolaston Pill, prior to sampling for age and growth analysis. Other prehistoric oaks lie in the mud in the background. On a bleak February afternoon, environmental archaeology is by no means a glamorous occupation.

FIG 55. Human footprints in the mud at Goldcliff. This was a group of adults and children, and they appear to have been walking slowly enough for the children to dance around the adults.

FIG 56. A close-up of some of the footprints shown in Fig. 55. Note the toe prints, showing that some of the people walked barefoot.

burned hazelnuts and charcoal dating from 5300 BC. Numerous lines of human footprints have been found, mostly high in the intertidal zone, where they give an amazingly vivid contact with family life several thousand years ago. The earliest, dating from 5100 BC, were found at Uskmouth, but nearby was a mattock fashioned from a deer antler that could date back to 5900 BC. One track at Uskmouth was made by a man (who would have needed a modern size 9 shoe) who walked at 110 steps/minute; another was smaller, and a third was clearly a child (Aldhouse-Green et al., 1992). At Magor Pill, footprints were left by a large chap, standing 2m high, who would have required size 12 shoes today. In 2001, 35 sets of Mesolithic footprints were found east of Goldcliff(Bell et al., 2001), together with prints of red deer and small gulls. Judging from stride length, imprint length and width, the group included men, women and children. Most walked barefoot – we can still see the toe prints – but a few just might have had shoes, and they were mostly walking either directly out to the sea, or back, though one child could be seen changing direction abruptly. One track of an adult walking south was matched by a nearby identical track walking north, perhaps one individual out on a day-trip (Scales, 2002). Touchingly, groups of imprints appear to be adults walking to the shore with children dancing around them (Figs 55 & 56).

Elsewhere in the Lower Wye

The Wye gorge and the Severn margins are atypical environments, and we are still left to speculate about the early environment of the bulk of the Lower Wye. Flints dropped by early Mesolithic (8000-6000 BC) hunter-gatherers at Doward, Llanishen, Drybrook and adjacent limestones (Walters, 1992; Walker, 2004) confirm the impression gained from the levels that there were very few places that these people did not reach, and that locally, at least, they must have considerably modified the vegetation. Interestingly, flint is not naturally found in Herefordshire, so the many Mesolithic flints found in that county must have been imported. Later Mesolithic remains have been found on both sides of the Wye, including occupation sites and seasonal camps used as bases for hunting concentrated on the limestone plateau by the upper gorge (Doward, Huntsham Hill) and in the St Briavels hinterland (Nedge Top, Bearse and Clanna).

Peat deposits formed in marshes in the bed of a wandering back channel of the Lugg at Wellington, just to the north of Hereford (Dinn and Roseff, 1992; see Chapter 2), gave some hints about vegetation development. About 5750 BC, woodland dominated by oak, lime and elm occupied the floodplain, with alder carr containing stinging nettle, elder, thistle and blackthorn filling a dip in the gravels. Another fascinating insight came from deposits in the Lawn Pool in

TABLE 8. The prehistoric sequence of vegetation around Moccas Park, as revealed by pollen preserved in the sediments of the Lawn Pool.

| ESTIMATED PERIOD (YEARS BC) | MAIN POLLEN TYPES AND CHANGES | PROBABLE VEGETATION |

|---|---|---|

| Early medieval to prestent day | Oak and grass common, with small amounts of elam, alder, sallow; negligibel birch, hazel, lime; no cereals or bracken | Oak-dominated parkland |

| Iron Age or Romano-British | Oak and grass abundant; hazel almost vanishes; alder, elm, birch at low levels; lome absent; cereal pollen consistently present; bracken rare | Small cultivation patches in open, grazed woodland |

| Neolithic to Bronze Age | Initially high proportion of grass and umbellifers withe some bracken, followed by steep declines; loss of lime; oak initially reduced, latterly increases sharply; hazel remains common; alder, sallow and birch increase; elm at low levels | Pastoralism in open woodland, possibly withe informal coppicing of hazel |

| 3000-1000 | Oak, hazel, with diminishing lime, elm, and small amouts of alder, birch; increasing grass and umbellifers | Possible pastoralism in increasingly open woodland |

| 5000-3000 | Oak, lime, elm, hazel; pine remains common, but declines eventually; small amouts of alder and birch; minimal amouts of grass | Closed mixed deciduous woodland withe small openings |

| 7300-5000 | Steadily increasing oak, hazel, elm; decreasing birch, pine; decreasing grass and ruderals | Closed oak-elm woodland with hazel below steadily replacing open birch-pine |

| About 7600 | Birch, pine, hazel, with much grass and ruderals | Open birch-pine woodland |

Source: Review of serveral sources by Lisa Dumayne-Peaty in Harding & Wall (2000). The profile was dated by analogy with radiocarbon-dated profiles elsewhere. Wetland pollen types, which presumably came from the Pool’s fringing vegetation, have been omitted.

Moccas Park, a natural depression left in early postglacial times by an extinct channel of the Wye, which showed an essentially natural progression from open birch-pine woodland to closed mixed deciduous oak-lime-elm-hazel woodland, before pastoralism eventually converted it to oak wood-pasture (Table 8).

The only bog with the potential to yield a long vegetation history, Cleddon Bog near Trellech, was recently sampled by Richard Bradshaw and Claire Jones. They tell me that preliminary results from their 140cm core (covering perhaps most of the last 10,000 years) indicate that the early to mid-Holocene forest thereabouts was dominated by alder, hazel and oak with some lime, birch, sallow, holly and ivy, but there was also a good deal of grass pollen, suggesting that the forest was open, grazed and burned.

Summarising, the pre-Neolithic environment is envisaged as a world of dark forests, dominated by lime, oak, elm, hazel and alder, interspersed with marshes, with limited tracts of park-like woodland kept open by cattle and deer, and limited clearings by Mesolithic people. Marshes were widespread on floodplains, the estuary margins, heavy-soiled plateaus and seepage zones on slopes. Grassy areas would probably have been commonest on thin soils on outcrops and some of the floodplain marshes. This is what we call the original-natural environment, neither constant nor free of human influences, but largely dominated by natural processes and patterns, and possessed of a fauna and flora that arrived without the aid of people.

THE PREHISTORIC SUCCESSION: NEOLITHIC TO IRON AGE

During the Neolithic period, agriculture developed alongside hunting; settlements were established throughout the Lower Wye; most of the original forests were cleared; and the remaining woodland was used and modified. Metalworking skills were added in the Bronze Age. The landscape was transformed, but we have only patchy archaeological evidence to indicate how it changed.

The most complete picture has emerged from the Caldicot Level. The Neolithic and Bronze Age landscape was a mosaic of wet woodland, reed swamp, shallow lagoons, raised bogs and limited areas of wet heath, drained by tidal rivers and freshwater streams running from the uplands, and periodically inundated at its margins by marine transgressions. Marshland though it was, the Level was well used by people. Flints have been found in several places, possibly lost by people roaming from camps on the fen margins, and, occasionally, the skulls of the people themselves come to light. In the Nedern valley just to the east of Caldicot Castle, excavation of an infilled ancient channel revealed clearance of original lime woodland in the early Bronze Age, some cultivation of cereals, and a long history of pasturage until marine inundation ended human activity in the Iron Age (Nayling & Caseldine, 1997). The Bronze Age farmers constrained the channel with a weir constructed of hazel piles, and in 990 BC, as the marine influence grew, a new bridge of oak and ash was constructed, together with a fish weir made of hazel. On the Severn shoreline, tracks made of brushwood pegged into the ground have been dated to around 1200 BC.

These activities must have been disrupted between 1450 and 500 BC, for the sea inundated the whole of the Level, save for parts of the back fen. Even so, Iron Age people continued to use the salt marsh: timber buildings and further brushwood tracks dating from around 250-100 BC have been exposed along the length of the modern intertidal muds. The timbers evidently came from nearby wet woodland – mainly alder, with some oak, birch, elm, maple and willow (Brunning et al., 2000) – and they were surrounded by hundreds of impressions of cattle footprints, suggesting that the marshes were used as pasture.

Changes in the surrounding uplands have been revealed by pollen in the peat (Rippon, 1996; Caseldine, 2000). Forest clearance started in the late Mesolithic (4300-4100 BC), continued in the early Neolithic (3700-2800 BC) and intensified around 1850 BC, but there were also periods of woodland regeneration. Elm and lime declined, oak remained common, ash increased, and the pollen of ribwort plantain appeared, which suggests clearance for agriculture of what we would now call ancient woodland and patchy regeneration of secondary woodland on cleared ground. Some of this early disruption may have been due to forest farming, i.e. cutting leaf fodder for animals grazing in the forest, and certainly there were periods when lime woodland regenerated, perhaps by regrowth after lopping (Nayling & Caseldine, 1997). By the Iron Age, most woodland had been replaced by pasture with limited amounts of cereal cultivation. Direct evidence of forest composition in the uplands came from Rowena Gale’s examination of charcoal in the caves of the gorge: the early pine-hazel-yew woods had given way by the Bronze Age to woods of hazel, ash, oak and yew. Beech colonised by the Iron Age.

Elsewhere, the evidence of human activity is limited, but Neolithic and later people clearly occupied the whole of the Lower Wye (Walters, 1992). Numerous arrowheads have been found that indicate widespread hunting. Flint scatters suggest possible settlement sites, though the settlements were probably seasonal and temporary. Bronze Age inhabitants left cremations, burial sites, flint scrapers, axes, spear tips, ornaments and residues of metalworking. They also dragged three huge conglomerate boulders for at least 1km to erect the Harold Stones at Trellech (Fig. 57). Why, we know not, but standing stones at Huntsham, St Briavels and Tidenham may mark ritual sites or routes. Iron Age people left pottery, glass beads, ritual objects, weapons and numerous hill forts. North of Caerwent, the Silures occupied the Llanmelin hill fort, and an unknown tribe occupied the Dean. Along the Wye fortified towns were built in prominent positions at Pierce Wood, Symonds Yat, Caplar Camp and elsewhere, but the wooden farmsteads that were presumably scattered about the hinterland have left only crop marks.

Significantly, some places seem to have been occupied continuously since the later Mesolithic or Neolithic, notably the Bearse area of St Briavels, Huntsham Hill, the Doward and around Trellech. Conversely, there are also many signs of change. Thus, the Bronze Age barrows found in Lower Hale Woods and Tidenham Chase, both ancient woods, were presumably built, like most barrows, on open ground. Likewise, the ‘hill forts’ at Pierce Wood and Symonds Yat were probably abandoned by the Roman period and are now within ancient woodland.

Putting all the hints together, we see a prehistoric landscape that already has many elements of the modern pattern. The plateaus were enduring centres of prehistoric activity, particularly on the limestone, where people lived,

FIG 57. The Harold Stones at Trellech, erected 3,500 years ago by Bronze Age people, who must have transported these Quartz Conglomerate blocks at least 1.3km.

cultivated, and buried their dead. Presumably, the whole district was crossed by a network of well-marked trackways. Occupation and defensive sites were concentrated in prominent locations at the plateau fringes. The steepest slopes – usually the upper valley sides – and perhaps parts of the floodplain must have remained well wooded, whereas gentler slopes, usually with deeper, more fertile soils, must have been farmed. In fact, the alluvium in the Lugg showed an increase in erosion and alluviation from the Neolithic onwards, suggesting that significant amounts of land were cleared and cultivated 5,000 years ago (Dinn & Roseff, 1992). Floodplains, too, were occupied – indeed, that is where most Neolithic artefacts in Herefordshire have been found – and occasionally used to bury the dead: witness the Bronze Age barrows that stood on the Lugg floodplain at Wellington. Some woodland probably remained along stream banks and on swampy ground, but the carrs of the Severnside levels had been cleared, and both the Severn marshes and poorly drained, infertile depressions on the Trellech plateau developed into bogs. One assumes, too, that the intensity of human impacts was uneven. Thus, the Severn fringes and adjacent uplands must have been a hive of activity, but a core of relatively inaccessible ground could have remained in the gorge from Penallt to St Arvans and from Redbrook to Tidenham.

THE ROMANO-BRITISH PERIOD (AD c.50 – c.400)

The Romans came to the Wye Valley about AD 50 and soon established a military iron-working centre and posting station at Ariconium (Weston-under-Penyard), but they took 27 years to subdue the Silures, who operated from Llanmelin hill fort near Caerwent. The iron industry expanded massively in the second century, exploiting the ore deposits in the Crease Limestone outcrops from Lydney through Staunton to the Doward, Lydbrook and Ruardean. Smaller ore bodies west of the Wye, such as around Trellech, were also worked for a limited period. Ore was smelted at Ariconium, Blestium (Monmouth), Staunton, Coleford, Whitchurch and Bishopswood, where huge volumes of slag were deposited. Economic recession early in the third century was partly reversed, but most of Ariconium became derelict in the fourth century, even as the settlement at Lydney expanded.

Romans and native tribes occupied the whole of the Lower Wye. Garrisons were established at Ariconium and Blestium, and to the west of the Wye at Isca (Caerleon) and Burrium (Usk), with subsidiary forts at, for example, Coed y Caerau, near Caerleon. Tribal cities were created at Magnis (Kentchester, west of Hereford) and Venta (Caerwent). Temples were built at Coleford and Lydney. From the early second century the elite built villas at Huntsham, Hadnock and in a line along the Severn from Chepstow, Boughspring and Lydney to Blakeney. Located in warm, well-drained sites on lower slopes with good access to productive land and mostly with views over the Severn and Wye, these were the ‘big houses’ whose occupants were engaged in farming and often also smelting. A pottery kiln operated at Caldicot. Early in the fifth century the empire collapsed and even the fine villas were abandoned.

The Romans also constructed a network of military roads that had much in common with the modern road pattern. The main artery ran along Severnside near Chepstow and crossed the Wye via a bridge just to the north of the castle in Alcove Wood (Hamilton-Baille, 2002), another ran along roughly the modern A40 from Monmouth northeast to Ariconium, and another passed through Dore to Kentchester. The Severn and Wye also formed important transportation routes, with many small landing places.

Throughout these 400 years little or none of the Lower Wye would have been ‘remote’. The detailed pattern of land use remains unclear, but Romano-British society certainly controlled much of the environment. Charcoal, which was required for iron smelting, probably came from renewable coppice woods, though there is some suggestion that, during the second century, woodland west of the Wye might have been destroyed enough to curtail iron production. Only central Dean may have remained remote, for no settlement was permitted after AD 75. Indeed, Walters suggested that a state official might have been appointed to administer the iron and other resources of the Dean at about this date. Perhaps it was already reserved for hunting, a thousand years before it became a royal forest.

Quite where Roman farmland was located is difficult to determine, but it was probably where it is now. Sherds are scattered over the St Briavels plateau, which implies widespread farming in a district that was farmed in the early Neolithic, and is still farmland. At Stock Farm, Clearwell, a late Romano-British site was found on land that was assarted in the thirteenth century, i.e. it was abandoned to woodland during the post-Roman centuries (Atkinson, 1986). In the specialised environment of the Caldicot Level, the Romans drained the marshes along the foreshore, but had little use for the back marsh (Rippon, 1996). The fen edge at, for example, Undy and Caldicot was a focus of settlement, and concentrations of Roman material around Goldcliff Point and Magor Pill testify to the use of the shore and inlets. A fourth-century boat constructed from oak planks was found at Barlands Farm (Nayling & MacGrail, 2004).

DARK AGES: POST-ROMAN TO DOMESDAY BOOK

This period of over six centuries is not as obscure as its popular name indicates: indeed, it is now known as the early medieval. Following the loss of Roman stability and organisation, various groups competed for control of the land, and by the seventh century the Lower Wye had become a borderland between Celts and Saxons (Walters, 1992). British resistance is associated with the names of Vortigern, Merlin and Arthur, but these seem to be idealised personifications established by Geoffrey of Monmouth, a twelfth-century historian (Thorpe, 1966). Saxons were repelled at Tintern about 600 and as far north as Dore, where they ‘destroyed’ the land, but during the seventh century they appear from place-name evidence to have established settlements in the Dean and south Herefordshire. The Dean became part of Mercia in 629, and about 780 Offa, the greatest Mercian king, built his famous dyke (Fig. 58) to contain the Welsh (though there seems to be some doubt that the dyke to the east of the Lower Wye was part of these defences). Vikings ravaged Severnside in 910 and 914, and raided as far as Archenfield. The Danes arrived in the late tenth century and took over Mercia in the early eleventh century, but the Welsh continued to raid into England.

FIG 58. Offa’s Dyke at the top edge of Caswell Wood. At many points the dyke runs along the break of slope, where it takes the form of massive earthworks on which beech-yew-holly woodland has developed.

In 1065 Harold conquered Gwent and annexed it to Hereford, but was defeated by the Normans a year later.

Summarised thus, the Lower Wye appears to have suffered prolonged disorganisation and devastation, but the land may not have been severely affected. Records survive from as early as 575 of land granted at Welsh Bicknor to support a religious community, which not only implies authority on behalf of the local king, but a landscape clearly divided by property rights. Monasteries and churches were founded in the seventh century at Llandogo, Lancaut and elsewhere, and further foundations followed at Tidenham about 700, Monmouth, Dixton and Trellech about 750, Sellack, Foy, Penterry and St Arvans about 800, and so on. These are just examples, but they represent the pre-Conquest distribution, which was concentrated almost wholly to the west of the Wye, where we find dedications to the sixth-century bishop, St Dubricius.

A well-organised, mixed landscape is revealed by surviving land charters. In the twelfth century, Llandaff monastery claimed title to many estates in east and northeast Monmouthshire and southwest Herefordshire, and backed its claims with extracts of ancient grants (Davies, 1978). Despite some doubts about their authenticity, these record plenty of cultivated ground, pasture, meadows and woodland, few marshes, recognisable roads that crossed rivers by fords and property boundaries that were often defined by banks and ditches, and much more unenclosed land than we have now. For example, the land at Welsh Bicknor granted to Dubricius in 575, which was presumably mainly pasture and arable, extended over the Wye ‘as far as the black marsh beyond the wood, and field, and water’. The boundary of Mathern in 620 mentions Pwll Merrick, a weir and landing places on the Severn. The Bishton estate in 710 extended to the Severn near Goldcliff, the boundary running through woods and along slopes and a dry valley on the uplands, but through marsh on the Level. When King Edwy granted Tidenham manor to the Abbot of Bath in 956 (Seebohm, 1905), the boundary ran from the mouth of the Wye to the headland (of an arable field) where the yew tree grows, and thence via a row of stones, a white hollow, a broad moor (i.e. swamp), a double ford and the [Horse] pill [near the Broadstone] to the Severn. According to Walters (1992), the white stones still exist beside a stream above Stroat farm and the ‘headland’ is still detectable as ridge and furrow. The c.895 boundaries of Caldicot and Mathern mention fish weirs on the Severn and Wye and moorings at the mouth of the Nedern. In the eighth century, the church and 750 acres (304ha) of land at Wonastow were exchanged for two horses, a hawk and a dog ‘which killed birds with the hawk’, the total being equivalent in value to thirty cows (Walters, 1992). Water mills for producing flour were situ ated on both sides of the Wye. Place names reinforce the impression that cultivation was expanding in the Dean and south Herefordshire, where the elements ‘ley’ (clearing in woodland) and ‘ton’ (farm or enclosed land) are frequent.

In 1085, when King William’s court was in Gloucester, a decision was taken to proceed with the survey that produced the Domesday Book (Moore, 1982; Thorn & Thorn, 1983). The Dean and its surroundings were part of Herefordshire in the early eleventh century, but parts had been transferred to Gloucestershire by 1085 and Redbrook, Ruardean, Staunton, Whippington, Alvington and other manors followed soon after. East Monmouthshire, though it was part of Wales, was administered by Gloucestershire, and southwest Herefordshire formed the semi-autonomous Welsh territory of Archenfield. The record itself was patchy: while some places were fully recorded, the records for Archenfield and Monmouthshire were incomplete and the Dean, being already a royal forest, was not surveyed. Even so, Domesday Book, the finest single source on the early landscape, casts a strong light on the state of the Lower Wye in the late eleventh century (Darby & Terrett, 1954; Standing, 2002).

Domesday Book records the plains to the south and west of Hereford as settled and prosperous, with a high density of people and plough teams, meadows and some woodland. Likewise, the Woolhope and Ross areas were also prosperous, with a dense population and a mixture of woods and meadows, though most of the woodland around Ross was in the forest. Mills were scattered along streams, fisheries operated mainly along the Wye, and eels were being caught on the Lugg. Archenfield had been laid waste by the Welsh in 1055, but it must have recovered by 1086, when many communities paid their dues in honey, a Welsh custom.

Further south, the Dean is usually assumed to have been sparsely populated, with little farming, but archaeological evidence suggests that this is an artefact of the record. Staunton, Redbrook and Whippington, all of which were in the forest, had been wasted, and Wyegate had recently become part of the forest. Alveston had a wood half a league long and wide, and Little Lydney (St Briavels) had one twice the size, both lying outside the forest. Then, as now, there was a well-wooded zone of farms and villages between the forest and the rivers, with much ploughland and some meadows. Settlements on the Welsh side also had ploughland and fisheries on the Wye. The woods were evidently managed, for the king received 40 shillings from ships going into the woodland and there is a reference to pannage for swine in Gwent. Most of the settlements on the western and southern fringes had fisheries on the Wye and Severn. Indeed, Domesday Book records that the various vills in Tidenham had a total of 65 fisheries, which were always associated with weirs, where both ranks of baskets (putchers) and wattle barriers (hack weirs, where fish were trapped or stop-netted from boats) were operated (Fig. 59). Fishing rights in the tenth and eleventh centuries implied

to Walters (1992) that salmon, sturgeon, porpoise and herring were taken, but the latter two probably came from the North Sea under exchange agreements with the Archbishop of Canterbury (Seebohm, 1905).

MIDDLE AGES: DOMESDAY BOOK TO DISSOLUTION

The Middle Ages saw the consolidation of England under Norman and Plantagenet rule and progressive attempts to bring Wales under English control, symbolised by the castles at Chepstow (Fig. 60), Monmouth, Goodrich and Hereford, and Marcher castles such as those at Raglan, Skenfrith and Grosmont. Well-endowed monasteries were established at Tintern and elsewhere, but they were dissolved in the 1530s and their land was redistributed. Forests were established under Forest Law, together with their private counterparts (chases, purlieus), and parks for deer and other stock. Expanding population in the early Middle Ages brought more and more land into cultivation, causing enough erosion to leave a thick deposit of alluvium in the Lugg and Wye (Dinn & Roseff, 1992), but after 1348 the Black Death killed so many people that the pressure on land was much reduced.

Many of the features of the modern landscape had already evolved by the eleventh century. The main concentrations of woodland had been defined, and by the thirteenth century many individual woods were known by versions of the names we use today. Even at a parish scale, the early medieval distribution of settlement, roads, woodland, meadow and common pasture is still recognisable, for some features survive and others have bequeathed names to the modern maps. True, there have been changes: for example, Trellech was once the second-largest town in Wales, but is now a village with an unusual layout and some fine earthworks. On the other hand, Coleford in Newland parish developed into a town, and Brockweir developed into a port on the river frontage of three parishes. Rivers and streams, which were crossed by numerous ferries and fords, were still used as fisheries and power sources for corn mills. No major road ran along the gorge, but people and goods moved freely along the river, impeded only by the numerous weirs.

Farming was generally mixed, with farms forming a mosaic of arable, pasture, meadow and small woods, and exploited the substantial tracts of ‘waste’ (unenclosed land beyond the frontiers of cultivation). Increasing enclosure before the fourteenth century led to some woodland clearance and marshland drainage, but these land grabs were much reduced in the later Middle Ages and

FIG 60. Chepstow Castle, rising like a continuation of the natural limestone cliff near the mouth of the Wye. The castle was built shortly after the Conquest. Wild cabbage grows on the cliff and the battlements in its only Lower Wye location.

may have been locally reversed. Outside the Dean, the common rights over the waste and within enclosed farmland were progressively reduced, which brought pressure on the remaining commons and some reduction in the number of trees on the waste.

Surviving records of land holdings and how they were used are voluminous from the eleventh century onwards, but space is insufficient to rehearse the intricate details of change. Instead, here and in the following sections, I pick out some important features of the period, and leave details of traditional land management to the habitat chapters.

Monasteries

The Cistercians were one of several orders that followed the Normans in from France (Williams, 2001). They tended to be frontiersmen, settling in remote, riverine locations, bringing waste, woodland and mires into cultivation. Tintern (1131), the first Cistercian foundation in Wales, was followed by Dore (1147) in the Golden Valley, Llantarnam (1179) at Caerleon and Grace Dieu (1226) west of Monmouth. Tintern was always among the largest Welsh monasteries and Grace Dieu among the smallest, but both were dissolved on 3 September 1536, when Tintern had 12 monks and 35 servants, but Grace Dieu had just the abbot and one other monk.

The White Monks quickly acquired substantial estates. Tintern Abbey had granges at Porthcaseg, Trellech and Rogerstone to the west, Modesgate (Madgetts) and Woolaston to the east, and several properties on the levels and adjacent uplands. Once acquired, the land was transformed: as Giraldus Cambrensis wrote in 1188, ‘give them a wilderness of forest, and in a few years you will find a dignified abbey in the midst of smiling plenty’. The buildings were made from local stone: Tintern was built of Old Red Sandstone quarried from Barbadoes Wood. Land transformation took the form of clearing (assarting) woodland and waste, draining mires, irrigation and marling of cultivated land with lime. In 1245, near Magor, Tintern was making ditches and maintaining sluice outlets to the Bristol Channel. In 1338 Grace Dieu obtained a lease on 36 acres (15ha) of waste adjacent to their Stowe grange, and no doubt brought it into cultivation. Woodland cleared before 1291 to the south of Tintern became a new grange that is now Reddings Farm. Assarting also followed at Woolaston and Monks Redding (Madgetts); in fact, Tintern’s monks continued to clear woodland until the early fifteenth century.

Individual farms generally mixed cultivation and pasturage, but there was clearly some specialisation according to the character of the ground. Thus, Rogerstone grange on limestone was mainly arable, whereas the Level was used as pasture. Woolaston grange, primarily arable, was a breadbasket, whose grain was transported by sea to the abbey. The 1387-9 accounts for Merthyr Gerain grange, north of Magor, showed that up to 124 labourers were employed on a single day for ploughing, sowing, hoeing, harvesting or threshing, producing mainly wheat, barley, oats and beans. Pastoral farming was supported by hay production, especially from meadows on the floodplains. The livestock were mixed: for example, in 1291 Tintern had 3,264 sheep, but in addition cattle were kept for milk, oxen and horses for work, and pigs, goats, chickens, geese, rabbits in coneygarths and doves in cots for meat. There were also gardens and orchards at the abbey and its granges, and farm produce was supplemented by fishing and wild venison. The scale of operations was perhaps indicated by Woolaston grange’s possessions at the dissolution: twelve oxen, two wains, two sound ploughs, two ox-harrows, two pairs of horse-harrows, one bull, one boar, one sow, six piglets, two geese, one cock and four hens.

Use and management of water was important. Not only were the marshes drained, and the drains constantly cleaned and repaired, but natural streams were also used. Thus, at Rogerstone, the mill pond was filled by damming streams and running leats from springs. Trellech grange used a water-filled depression as a source of power. In 1525, Tintern Abbey maintained a grinding mill on the Angiddy, with its dam, floodgate, millstone and hammer (for iron working). The marine and freshwater fisheries in the Severn and Wye, from which they took salmon and sardines, were important enough for Tintern to employ a guardian of the fisheries, who looked after the abbey’s rights in several weirs on the Wye and in ‘puttes and engens’ for catching fish in the Severn. In 1330, Abbot de Camme caused several weirs to be raised by nearly 2m, thereby impeding boats, including those carrying wine and food for Monmouth Castle. The bailiff and steward were sent from St Briavels Castle to lower them, but they were assaulted by a group of locals led by monks.

Forests

Medieval forests comprised land subject to Forest Law, which was concerned mainly with keeping deer. They were not necessarily well-wooded (Rackham, 1980), but in fact the forests around the Lower Wye did include substantial tracts of woodland. The principal forest, then as now, was the Dean (Hart, 1966), which occupied the triangle between the Wye and the Severn as far north as Ross. The Forest of Haye was used for hunting in the time of King Edward (before 1066), and in southern Herefordshire the forests of Trevil, Haye, Aconbury and Harewood formed an almost continuous tract from west of the Worm Brook into the high ground south of Hereford and on to the Wye near Hoarwithy (Robinson, 1923; Oliver, 1998).

The boundaries of the forests were adjusted many times during the Middle Ages, and were generally much reduced during and after the thirteenth century. Archenfield had been declared to be forest soon after 1066, but in 1251 the residents paid 200 marks to be (largely) quit of afforestation. Forests were reduced by granting woods and other land to the secular and ecclesiastical aristocracy as parks and chases. Thus, Trevil Forest, west of Kilpeck, extended to 1,214 acres (491ha) in 1214, but by 1230 it had been disafforested and granted to Dore Abbey and John of Monmouth. Monmouth Chase, including woods at Wyesham and Hadnock, was granted to the king’s brother, and Bishopswood to the Bishop of Hereford. Most of the grants from the Dean were peripheral, leaving the northern (Herefordshire) portion and the Wye hinterland as parks, chases and ordinary woods outside the forest. Alienation did not necessarily lead to woodland clearance, as a glance at the modern maps will testify, though some disafforestation was linked to permission to assart and bring waste into cultivation. In the Forest of Haye, for example, which occupied all the lands between the modern A465 and A466 south to Much Dewhurst, including the low-lying marsh around Allensmore, permission was given in 1261 to clear half the wood of Coytemor, leaving the other half as Coedmor Common.

In addition to clearance, the Dean’s woodlands were opened up by ‘clear-felling without enclosing, indiscriminate cutting, depredations, browsing, commoning, wind-throw, natural decay, and occasional fires’ (Hart, 1966, p. 51), and many granted woods were over-cut and rarely enclosed. Two forces were mainly responsible: the exercise of common pasturage rights by local inhabitants and utilisation of timber and wood, as fuel, charcoal for smelting, quarrels for crossbows, and buildings. A survey of 1282 revealed numerous clearings and waste, and Roger Taverner’s survey of 1565 records much waste and woods stocked with lopped trees ‘of great age’ (Hart, 1966, pp 251-73). By the end of the Middle Ages, the Dean must have looked less like a dense woodland and more like open parkland with extensive glades.

Caldicot Level

The process by which the Caldicot Level was recolonised during the Middle Ages can be read in the modern landscape (Rippon, 1996). Save for a few ditches surviving from the Roman occupation, the current pattern of drains and fields dates from after the Norman Conquest. Recolonisation required a sea wall to protect the marshes from marine inundation, a few embanked rivers (e.g. Monks Ditch) to carry water directly from the uplands to the sea, and a hierarchy of reens to drain the marshes via tidal sluices.

Early colonisation was concentrated on the slightly higher seaward ground, behind a sea wall that has since been lost. The large eleventh- and twelfth-century intakes to the west of Nash and Goldcliff, centrally around Redwick and Undy, and to the east around Caldicot, are now characterised by small irregular fields, many of whose boundaries effectively fossilise the meandering creeks of the former salt marsh. At Redwick, one can still trace the shapes of the early infields, the later open field of strips known as Broadmead, and several commons. Throughout, the back fen – the marshes between the drained intakes and the uplands – remained undrained. At this time, the intakes were used as arable, pasture and meadow, the salt marshes were seasonal pastures and the low-lying wetlands were mixtures of meadows, common pasture and fen-carr.

Later intakes were increasingly regular (Fig. 61). Most expanded into the back fens from the edges of the land already colonised. The rate of expansion declined from the mid thirteenth century onwards in response to increasingly frequent storms and floods and, after 1348, the reduced population and increasing social dislocation that followed the Black Death, but agriculture continued as a mixture of arable and pastoral farming with cattle and sheep. After several breaches,

FIG 61. Stages in the development of Caldicot Level. Small, oval enclosures were embanked in the post-Roman marshes to protect crops (2). With the construction of a sea wall in the early 12th century and associated embankment of watercourses, the coastal zone was progressively colonised, leaving Caldicot Moor as intertidal saltmarsh (3). Later, enclosures expanded into the back fen (4). From Rippon (2000), with permission.

the sea wall was rebuilt on its present line, and by the sixteenth century most of the Level consisted of drained farmland, permeated by a network of roadside commons. Marshes remained in the back fen and the extensive common of Caldicot Moor.

Commons

The system of private land subject to common rights and customary practices is one of the most ancient institutions of England and Wales (Hoskins, 1968). Commons were subject to rights over the land held by local residents (commoners), but the ground itself had a separate owner. Many were the residue of unclaimed land, open to all, and formerly beyond the confines of private property, which originally encompassed great tracts of woodland, moorland and marshland. They were progressively appropriated by the Crown as forests or by manorial lords, but the rights to pasturage, firewood, pannage, turf, etc. survived, though increasingly they were stinted (e.g. restricting the numbers of stock that could rightfully be run on a common), people who lived outside the manor were excluded, and rights were challenged by the owners of the soil. These restrictions were eased after the Black Death, when there was a prolonged retreat from marginal lands and extensive replacement of tillage by sheep and cattle pasture, but by 1480 common land and rights were again being whittled away, marginal common land and waste was again coming into cultivation, and new farms and hamlets were being established in remote places.

Nowadays we associate commons with rough grazing and scrub, but in the Middle Ages the most extensive were wood-pastures. These mosaics of open woodland, heathland and dry grassland subject to rights of pasturage, pannage (pigs, mast), estovers (firewood), bracken cutting, marl, etc., eventually developed under relentless grazing into heathland, grassland and scrub with few trees, though some were enclosed as coppices. Such commons were usually located on infertile soils, as the surviving examples at Garway Hill, Merbach Hill and Ewyas Harold testify. The Forest of Dean and its satellites, such as the Hudnalls, were by far the most extensive, but they were matched across the valley by Wyeswood Common, an extensive wood-pasture on the infertile uplands of the Trellech plateau.

Commons were also located on fertile and wet ground. Thus, common meadows filled the Wye and Lugg floodplains, their hay cut according to lots and the aftermath grazed in common (Brian, 2000). Undrained wetlands survived as common grazings, notably in Caldicot Moor and other back fens of the Caldicot Level. Open fields were infrequent in the Lower Wye, but several were grouped around Hereford and in the Caldicot Level. These were cultivated in strips, but the arable weeds, baulks and margins were grazed in common after the harvest. Many villages had village greens and more extensive commons, forming common pastures close to home. These and other commons were linked by funnel-shaped entrances to a network of roads and droveways where the verges were also treated as common pasture, and which were particularly well developed on the Level. The Severn salt marshes appear to have been a de facto common fishery.

Habitats

Monastic lands, forests, commons and the Caldicot Level are special cases, so it may be unwise to assess medieval habitat change from them alone, but they collectively occupied a substantial fraction of the Lower Wye, and the mixed monastic farms typified the period. Semi-natural habitats were clearly reduced: many individual woods were cleared; some wood-pastures were denuded by the sixteenth century; farming was intensive enough before the Black Death to erode soils into the floodplains; and extensive wild lands were lost when the Caldicot Level was reclaimed and perhaps also when some forests were alienated.

Even so, extensive semi-natural habitats remained, and they were well connected by modern standards. Heaths and wood-pastures in the Dean and on the Trellech plateau still bracketed the gorge, and the gorge was lined with woodland. The broad pattern of woodland and farmland changed little. Large areas were cultivated, but pasture and meadow remained abundant, well distributed and largely permanent. Wetlands were reduced by drainage, but remained extensive on Allensmore, the Wye floodplain and parts of Caldicot Level. Rivers and streams were well used, but still ran fairly wild. The semi-natural habitats were not only extensive, they also formed large blocks and were well linked by the gorge woodlands, the floodplain meadows, the mixed land types of individual farms, and the all-pervasive network of grassy roads and tracks.

DISSOLUTION TO THE MID TWENTIETH CENTURY

While the broad pattern of the modern landscape was well established by the sixteenth century, many details changed during the post-medieval centuries as medieval institutions declined and new land ownerships and uses developed.

Dissolution, deforestation and enclosure of commons

The Dissolution of the Monasteries led to a sudden and substantial redistribution of land ownership, though actual changes in land use may not have been great. The estates of Abbey Dore went to the Scudamores of Holme Lacy (Shoesmith & Richardson, 2000). Much of Tintern’s land went to the Dukes of Beaufort, who held it until about 1900.

Deforestation (suspension of Forest Law), followed by actual reduction in trees and woodland, was more gradual. Most of the forests in Herefordshire had been deforested by 1300, but the Forest of Haye survived until the woods were leased out in the sixteenth century and sold off between 1606 and 1707. In 1827 the forest was acquired by a Dr Prosser, whose solicitors compiled a historical account in which they recorded that most of the former forest was brought into cultivation around the 1720s, but that 94 acres (38ha) remained as pollards and underwood (Oliver, 1998). In 1788 encroachments on the Dean amounted to 589 cottages and 1,798 small enclosures, but they were mainly peripheral and the core remained intact (Hart, 1966). Around 1630, 3,000 acres (1,200ha) of Wentwood were enclosed by the Earl of Worcester (Linnard, 2000, p. 92).

Common rights diminished further. Some were lost with deforestation: in the Wentwood case, the tenants contested the loss of rights up to the House of Lords. Some wooded commons were broken up by unregulated squatting into landscapes of small, irregular closes, a transformation that overtook the Hudnalls at St Briavels and many other places around the gorge and on the margins of the Dean (Herbert, 1996). Parts of the great Wisewood Common on the Trellech plateau were also assarted into small fields, but the greater part was not enclosed until 1810, when it was partitioned between the Duke of Beaufort as landowner, local vicars as titheholders, and local commoners (Bradney, 1913). The Lammas meadows on the Wye and Lower Lugg floodplains were enclosed by piecemeal strip amalgamation and Parliamentary Act until, by 1900, only three remained (Brian, 2000). The Scowles near Coleford formed as a settlement on a common of Staunton manor.

About 1540 Archenfield was described by Leland as ‘full of enclosures, very full of corne and wood’, and before 1600 most of the open fields in the borderlands had been enclosed (Rowley, 2001). In 1695 Herefordshire was one of the most enclosed counties in England, only Kent and Essex being more enclosed (Oliver, unpublished). Indeed, the commons were always being encroached, though they remained important for many residents. Thus at Hope Mansell 390 acres (158ha) of waste and woodland known as the Bishop’s Purlieu were enclosed in 1807. The Ross commons, mainly the Broadmeadow (26ha) and the common arable fields of Cawdor, Berry and Pool (10ha) were enclosed in 1830 and sold to help pay for lighting the town and cleansing the pavements, and in 1861, 18ha in Ailmarsh and Coughton Marsh were enclosed. In 1835 wasteland on the Little Doward was enclosed, comprising 74ha of woodland, 4ha of waste, and 6-8ha of existing holdings (that were thereby legitimised). The 73ha of Little Birch Common on Aconbury Hill were enclosed in 1824. Sixty years later the Reverend J. Tedman (TWNFC, 1885, p. 297) recalled that this had been ‘an extensive common, on which were built many cottages, with large gardens enclosed from the waste. The cottages…from their well-cultivated gardens a good store of flowers, vegetables, strawberries & other fruits are produced for the Hereford market. The women and children collect in their season mosses and wild flowers for decoration, elderberries & cowslips for wine, nuts chestnuts etc selling them in Hereford Market.’ Exceptionally on the Caldicot Level, common fields and meadows remained large and numerous into the nineteenth century (Sylvester, 1958; Rippon, 1996), but by 1870 they were enclosed like the others under Parliamentary Act.

Rural development: country houses, industrialisation and settlement on commons

Numerous great houses and parks were built in the sixteenth and subsequent centuries, stimulated initially by the redistribution of monastic lands (Rowley, 2001; Whitehead & Patton, 2001). For the first time, land was used primarily for aesthetic rather than economic reasons. In the eighteenth century, Herefordshire had two influential landscape designers in Richard Payne Knight at Downton and Uvedale Price at Foxley, both influential figures in the development of the theory of the Picturesque and realising these theories on their estates. Thanks to their efforts, and those of professional designers such as Lancelot Brown and Humphrey Repton, parks were laid out and massive numbers of foreign trees were introduced into the landscape. At Stoke Edith, an old house was replaced, the park was redesigned, woodland was planted on the Woolhope hills, and the turnpike from Hereford to Ledbury was moved. Moccas Court was built in 1775-80 with a park landscaped by Lancelot Brown. Holme Lacy was built about 1680 for the Scudamores, the largest country house in Herefordshire. Further down the Wye, Courtfield, a Georgian house, was owned by a Catholic family, the Vaughans, and Troy House was built outside Monmouth about 1673. In the gorge Bigsweir House was built about 1740 while Piercefield was built and rebuilt in the eighteenth century. Some parks, such as Kentchurch and Holme Lacy, were based around medieval parks; others, notably Moccas, developed out of wood-pasture commons; and some, such as Piercefield, were newly formed out of ordinary farmland. As the great houses were built, trees and some new woodland were planted, and much of the land was used as pasture. Wyastone Leys with its deer park was built on the Little Doward on what had been common land until 1833.

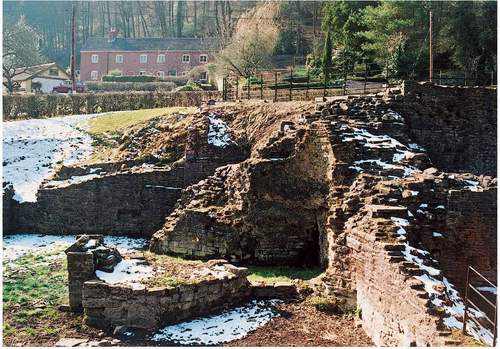

The Wye gorge developed into an important industrial region between the sixteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. From Bishopswood southwards it afforded swift streams to power mills, charcoal from woodland, and the river as a route for importing ore and exporting products (Barber & Blackmore, 1996). The Angiddy ironworks was built in 1550, where until 1828 it smelted imported iron ore in a charcoal-driven blast furnace. Then, instead of modernising, it closed for lack of a nearby source of coal (Fig. 62). The first British water-powered wire-drawing works were constructed at Tintern in 1565. A tin-plate works remained open until 1901, by which time a railway branch line had been built over the Wye to serve it. In the seventeenth century other iron furnaces were built at Coed Ithel and Woolpitch Wood. Upriver, overspill wireworks were built in the Whitebrook valley and later transformed into a paper mill. From 1692

FIG 62. Remains of Tintern Abbey furnace in the Angiddy valley. This started production in the sixteenth century and remained in use until 1828, the last blast furnace to use charcoal. Behind stand the workers’ cottages.

until the late eighteenth century, Cornish copper ore was smelted at Redbrook. Later, tin-plate manufacture took over, and at one stage Redbrook produced the thinnest steel sheets in the world, but the works finally closed in 1961. Over the same period, iron working was revived in the Dean (Nicholls, 1866), thereby extending the scowles, and coal was mined extensively, leaving slag heaps and a network of former tram roads. Metal working declined and died out in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and today few free miners remain to win coal in the Dean.

The impact of manufacturing can be appreciated from those who saw it. In 1828, a German tourist (quoted in Barber & Blackmore, 1996) described Tintern:

The country [is] deeply wooded and verdant; but in this part it is enlivened by numerous ironworks, whose fires gleam in red, blue and yellow flames, and blaze up through lofty chimneys, where they assume at times the form of huge, glowing towers.

And Arthur Cooke (1913) described

the dense dark clouds from tin-plate works [at Redbrook] established more than fifty years ago…working night and day. The works are open to the cinder-covered road, and we exchange the sylvan peace and beauty of the [Newland meander] valley not five hundred yards above for the sound and sight of clanking roller-mills, the glow of furnaces, and red-hot plates of iron drawn from the rolls by bare and brawny arms. Below the works the stream is anything but good to look upon.

Commons were often replaced by squatter settlements, tiny cottages among small, irregular closes (Fig. 63). This is the small-field landscape that is such a feature of the Doward, Kymin, Hudnalls, Lydbrook, Ruardean Hill and other places in the gorge and the Dean fringes, and less extensively in east Monmouthshire (e.g. the Narth) and Herefordshire (e.g. Little Birch, Walford, Common Hill at Fownhope). Squatting on the commons at Coppet Hill and Symonds Yat was initiated in the seventeenth century by miners. Settlement on unenclosed wood-pasture in Bicknor Bailiwick developed into the extensive suburbs of Berry Hill, thereby separating Highmeadow Woods from the Dean.

FIG 63. Remains of a very small cottage in the Hudnalls, possibly a residence for men fashioning Quartz Conglomerate blocks into millstones. The high tide of eighteenth-century squatting in the common wood left many small enclosures and habitations, but they were abandoned in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and allowed to return to woodland, leaving a miniature version of the landscape of New England.

Transport and tourism

The Wye remained a major artery for transporting wood, ore and finished products until the early twentieth century, serviced by trows, flat-bottomed craft that plied the Severn and neighbouring rivers (Green, 1999). Throughout the Middle Ages anyone could navigate the Wye: indeed, in the thirteenth century Edward I declared a Common Right of Navigation (Stockinger, 1996). However, weirs remained an issue between the fishery owners and the navigators until the sixteenth century, when there was still a weir at Monmouth 3m high with a hedge on top, which was a complete barrier to navigation. The first attempt to improve the navigation of the Wye and Lugg was made in 1662, but this was soon abandoned due to the strength of flow in the Wye. In 1695, an Act appointed Commissioners to remove weirs and compensate owners, but removal destabilised the channel and caused uncontrolled shoaling, and the loss of water power actually hindered navigation and reduced the effectiveness of mills. In 1811, a horse-towing path was opened from Monmouth to Hereford, which relieved the gangs of bow-hauliers who had previously manhandled the boats upstream (though they were still needed to get boats up to Monmouth until at least the mid nineteenth century) (Fig. 64). The opening of the Gloucester to Hereford canal in 1845, followed shortly by the railways, effectively ended the river navigation, though pleasure craft continued to ply the Wye, and one timber haulier used trows to take timber down from Monmouth into the early twentieth century. The tidal section remained busy into the 1930s, allowing, inter alia, Newport Docks to be built with stone from Pen Moel cliffs. In the early nineteenth century, New Weir was the last to be dismantled.

By the mid eighteenth century Herefordshire, which was one of the earliest counties to be turnpiked, had a well-developed road network. The main road between Monmouth and Chepstow was completed in 1824. The railways were

FIG 64. Bow-hauliers north of Goodrich, as shown in a print after an 1830s watercolour by Peter de Wint. While craft were being towed upriver, at least one river bank must have been kept free of trees.

completed between 1855 and 1876. The Wye Valley lines followed the floodplain and were always minor routes on which staff became local personalities (Handley & Dingwall, 1998). The main line along Severnside linked the valley to Bristol, Gloucester, south Wales and the national network, and there were other connections from Ross and Hereford. The railways killed the river traffic and the roads eventually killed the railways, but, combined, they brought the Lower Wye firmly within reach of growing urban populations in Newport, Gloucester and Bristol.

The tourism that started with the Romans and was a small element in monastic life developed strongly during the eighteenth century, when regular coach routes were established. The Wye Tour became established (see Chapter 1), and created an incentive to save the abbey remains at Tintern and construct the woodland walks at Piercefield and Coldwell Rocks. Although the Wye Tour faded by 1900, tourism was actively promoted through the twentieth century by numerous guidebooks. The nineteenth-century rise of field sports – hunting, shooting and fishing, with their attendant army of gamekeepers and bailiffs – facilitated the survival of scraps of wild country, but inflicted immense harm on wild predators. Tourism probably had little impact on habitats before 1950, but generated a fine collection of riverside hotels and landmarks, such as the banqueting house on the Kymin.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, suburbs expanded over nearby farmland at Chepstow, Monmouth, Ross and Hereford, and Coleford sprawled over the Dean fringes. At the same time, rural settlements, including the squatter houses on the former commons, were increasingly colonised by people from the towns with urban attitudes and no connection to agriculture. Gardens that were once concentrated round Roman villas and monastic herb gardens spread further into the countryside, increasing thereby the opportunities for species to escape into the wild.

Farming and forestry