CHAPTER 6

Grassland and Associated Farmland Habitats

FARMLAND IS THE dominant land type of the Lower Wye. The rivers, woods, cliffs and coastlands get all the publicity, but farmland occupies 70% of the land. Farmland is a complex mosaic of habitats: not just fields, but also linear elements (hedges, road verges, streams), patch habitats (pits, ponds, patches of scrub) and surviving unenclosed commons. The commons vary from grass to heath, bog and scrub, and the remaining agriculturally unimproved pastures and meadows still have wet hollows and dry banks, but most fields have been homogenised as habitats by cultivation, ‘improvement’ or prolonged sheep grazing. Farmland also includes many woods, but these were traditionally excluded from agricultural tenancies and are still managed separately.

Gilpin preferred grass to cultivated ground: ‘pasturage not only presents an agreeable surface: but the cattle, which graze it, add great variety, and animation to the scene’. Indeed,

the meadows, below Monmouth, which ran shelving from the hills to the water-side, were particularly beautiful, and well-inhabited. Flocks of sheep were every where hanging on their greet steeps; and herds of cattle occupying the lower grounds. We often sailed past groups of them laying their sides in the water: or retiring from the heat under sheltered banks.

Naturalists, however, took little notice. Judged by their Transactions, the Woolhope Club took the Herefordshire grasslands for granted. Oddly, this mild apathy continues to this day, for few of the grasslands have been recognised as SSSIs, and none as an SAC. With few exceptions, therefore, they are deemed to be just ‘ordinary’ examples of their kind, unworthy of special attention. And yet the Lower Wye contains lowland landscapes still dominated by semi-natural grassland, the largest surviving Lammas meadow, some amazingly colourful orchid meadows, and a range of grasslands from acid heaths to brackish meadows. Moreover, the grasslands have become the priority for conservation: they are as much part of the landscape as the woods and the river, yet they are a good deal more vulnerable than either to changes in land use.

This chapter emphasises the semi-natural pastures, meadows, heaths and mires that are, or were, either integral parts of farms and smallholdings or marginal supplements to them. Despite their reduced circumstances, they are still the main repository of biodiversity outside woods. Farm woods were included in Chapter 5, stream habitats follow in Chapter 7, and linear habitats are described in Chapter 8.

NATURAL GRASSLAND

Grassland is usually regarded as man-made, initiated by Neolithic farmers as they cleared woodland and created pastures, and certainly open habitats expanded rapidly in the Neolithic (Chapter 4). On the other hand, open habitats were widespread at the last glaciation, the prehistoric landscape was full of large herbivores, such as deer and wild cattle, and salt marshes fringed the Severn even at the forest maximum. No doubt open habitats passed through a pinch-point from about 8,700 years ago, and this may have lasted for 3,000 years during which the treeless ground was probably limited to shoals in rivers, large inland cliffs, salt marshes, bogs and marshes on floodplains and the levels. These permanent openings may have been supplemented by ephemeral but more widespread grassy openings if Frans Vera (2000) is right (Chapter 5). If the floodplains and infertile sites within natural forests were dynamic mosaics of glades and parkland, maintained by prehistoric deer and wild cattle, then grassland would have been widespread, even when forests dominated the land.

On this interpretation, the Lower Wye grasslands are not wholly man-made, but have direct links with prehistoric natural grasslands. Heaths and acid grasslands may have started as mosaics of glades; floodplain grassland could be a modified form of the natural marshland; brackish grassland along the Severn and Lower Wye could well be similar to the vegetation grazed by red deer and aurochs; and ordinary meadows and pastures may have been assembled out of species in ephemeral woodland glades.

Leaving aside the salt marshes and brackish grassland, the most natural remaining grassland may be the small patches of turf on the tops and ledges of the Seven Sisters, a group of rock towers formed in Crease Limestone on the north side of the upper gorge, where the soil is thin, the ground dries rapidly, and the vegetation is exposed to the full force of the summer sun (Fig. 89). The ground has obviously not been farmed, and outcrops have always been surrounded by ancient woodland. The flat tops are bare in places and their immediate hinterland is thinly wooded limestone pavement. Trees and shrubs try to colonise, but they are repeatedly set back by drought and browsing, so the grassland remains open. The climate and site conditions around the exposed rocks must almost match the conditions found in the Cevennes of south-central France.

The Seven Sisters grassland cannot cover more than 200 square metres, and for such a small area the variety and rarity of the plants is amazing. Parts of the outcrops are covered by sheep’s-fescue, red fescue, quaking-grass and false brome turf, but this is mixed with floriferous clefts and ledges that look like a bright, garden rockery (Fig. 90).

FIG 89. Grassland on the top of one of the Seven Sisters, a limestone rock tower on which several rare species persist in grassland isolated among ancient woodland. Drought prevents trees and shrubs from persisting. Large-leaved limes and whitebeams, rooted below the summit, are coming into leaf. The visitors are members of the Botanical Society of the British Isles.

FIG 90. Horseshoe vetch growing among the patchy turf on the parched top of one of the Seven Sisters rocks.

Many are widespread species of limestone grassland, such as hairy rock-cress, glaucous sedge, dropwort, common rock-rose, mouse-ear-hawkweed, common milkwort, salad burnet, small scabious, saw-wort, wild thyme and miniature dandelions, but several rarities are mixed in, notably lesser calamint, fingered sedge, dwarf sedge, soft-leaved sedge (Fig. 91), bloody crane’s-bill (Fig. 92), horseshoe vetch, hutchinsia, reflexed stonecrop and wood bitter-vetch. Diversity is further increased by wood-edge species, such as madder, wood sage and early dog-violet. Most species are inconspicuous, but a few are abundant and colourful enough to produce displays of purple (bloody crane’s-bill, saw-wort) and yellow (horseshoe vetch, rock-rose, dandelion and mouse-ear-hawkweed) in early

FIG 91. Soft-leaved sedge, a rare species of dry limestone grassland, on the Seven Sisters rocks with bloody crane’s-bill.

FIG 92. Bloody crane’s-bill, a characteristic species of scrub margins on the fringes of limestone outcrops in the Wye gorge.

summer. To this have been added splashes of magenta, for red valerian has naturalised here just as copiously as it has on walls and in gardens. If we disregard the valerian, we must be looking at a scene that has hardly changed since prehistoric hunters from the Madawg rock shelter below surveyed their territory.

The Seven Sisters may always have had the greatest concentration of these species, protected by the greater size of the habitat and perhaps greater extremes of drought, but several other cliffs in both the upper and lower gorge, such as Pen Moel Rocks and the Wyndcliff, once had similar rock gardens supporting the same suite of species. Sadly, these have declined enormously during the twentieth century to the point where several species on most outcrops are extinct. The rocks are still there, but they are more shaded by trees following the end of coppicing and reduced pasturage on the fields above. Some populations survive, and at Tidenham Chase soft-leaved sedge has bucked the trend by colonising old limestone quarries on the plateau nearby.

ANCIENT AND MODERN GRASSLAND

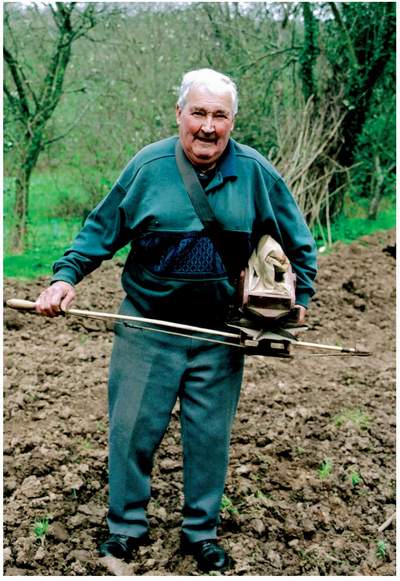

Whatever its origin, most grassland is maintained by hay cutting or grazing by farm animals, and has been so for millennia. Mixed farming continued into the twentieth century and persists now to a limited degree, so it is possible that some land on commons, steep ground or floodplains has an unbroken history of grass cover stretching back hundreds or thousands of years. Most land, however, has changed from ploughland to grassland and back as social and economic circumstances have fluctuated. When land reverted to grassland it either ‘tumbled down’, implying that the weed growth after the last arable harvest was simply grazed until it became grassland, or was sown with barn sweepings from nearby fields (Fig. 93). Either way, ancient and new grassland consisted of native grasses and herbs of local origin.

Maps produced in the 1840s for the Tithe Apportionment give a wonderfully clear picture of the pattern of traditional land use during a fairly prosperous era for farming, and show that the pattern of grassland was controlled by the settlement pattern and natural topography. For example, the Newland and Hewelsfield maps, which cover the gorge and plateau from north of Coleford to the borders of Tidenham Chase, show a mosaic of woodland, pasture, meadow and arable in roughly equal amounts. Meadows were concentrated around the town of Coleford, the villages of Newland, Clearwell and Hewelsfield, and isolated farms, such as Stowe, Caudle and Longley. They were also concentrated along lower slopes of valleys (which is generally where the villages and farms were located) and the floodplain of the Wye. Pasture was concentrated in similar locations, so the pastures and meadows together formed a single network of grassland habitats, with arable mainly on the plateau, especially around Hewelsfield, Wyegate, Clearwell and St Briavels, and some of the slopes below the woods, but above the meadows and pastures in the valley bottoms. Small orchards were concentrated around villages and within squatter settlements. Interestingly, several enclosures with ‘meadow’ field names were used as pasture or arable in 1841, indicating earlier changes from permanent grass to cultivation and between meadow and pasture. Only St Briavels lacked meadows in the village, but it was surrounded by ‘pasture’, some of which carried meadow field

FIG 93. Stan Scrivens of Brockweir illustrates an aspect of traditional grassland management. The instrument is a fiddle, used to broadcast barn sweepings and other seed when renewing or repairing pastures and meadows.

names. The maps also carry clear signs of land drainage: in St Briavels, for example, ‘Hollow Marsh’ and ‘Petty Marsh Piece’ were both used as arable.

The amount of ‘permanent grass’ remained substantial until well into the twentieth century. When the Land Utilisation Survey (LUS) was completed in 1935-6, 62% of Herefordshire was under permanent grass, a further 8% was rough grazing, and arable and orchards occupied just 15% and 4% respectively (Broughton, 1941). Ministry of Agriculture statistics came up with slightly different figures, but they revealed that 27% of the permanent grass – about 35,000ha – was cut for hay. The highest concentration of arable was in south Herefordshire, but even here large, unbroken expanses of cultivation were unknown. The actual distribution can be seen on the LUS maps, which show blocks of arable on rising ground near the Wye at Walford, Fawley and Foy, and a substantial scatter in southwest Herefordshire and the Woolhope Dome, but very little around the gorge, and none on the floodplains. In east Monmouthshire, nearly every patch of woodland was said to have a fringe of heath and rough grazing (Clarke, 1943). The Ross district was known as sheep and barley country, with fine dessert apple and plum orchards at Glewstone, Sellack and Aston Ingham. Grassland was poor and tended to burn out in summer, save for the valuable Wye floodplain hay meadows, which remained green. Similar patterns were recorded in Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire. In 1941, just 0.2% of the Gwent Levels was ‘tillage land’, the rest being pastures in which ‘various pasture herbs were numerous, and their contribution to the herbage, especially the hay crop, was often considerable’ (Williams & Davis, 1946).

Agricultural census returns for Herefordshire from the mid nineteenth century onwards show that the area of arable and orchards peaked in 1870, when they occupied 39% of the county. Thereafter, grassland increased steadily until in 1938 it occupied 60% of the county. Simple calculations confirm that at least one-third of the permanent grass present at the start of World War II had originated in the previous 70 years.

Some grass was ‘improved’ well before the twentieth century. While the traditional method of ‘laying down land for pasture’ in Herefordshire was to sow ‘red and white clovers, trefoil, ray-grass and hay seeds from the loft or barn…with barley’ (Duncumb, 1805, p. 70), ‘artificial grasses’ (‘red clover, white clover, darnel, cockgrass, plantain; sainfoin or French grass in very few places’) were sown in Monmouthshire, and ash from the Sirhowy ironworks was applied as a surface dressing to poor grass. Harrowed in and rolled, it killed moss (‘in which the mountain districts abound’) and produced ‘a fine verdure’ (Hassell, 1812). Nevertheless, the first LUS maps show that the traditional pattern survived until World War II, when a 1939 survey of Herefordshire grasslands found that 60% were unimproved Agrostis-dominated swards (‘utterly derelict’), 3.6% were ‘infested’ with fern and gorse, less than 5% were rye-grass mixtures. By that time, R. G. Stapledon and others had demonstrated that greater productivity could be achieved by frequently ploughing and reseeding with cultivated varieties of grass, so they advocated ‘improvement’. Much grassland was ploughed and cultivated during wartime, and the search for yet higher productivity has continued to the present day. The greatest losses were in the English lowlands, where most old grassland had been replaced by arable or reseeded grass by the 1960s and an astonishing 97% of all the semi-natural grassland that existed in the mid-1930s had been destroyed by the mid-1980s (Fuller, 1987), i.e. built upon, ploughed, drained, herbicided, or so heavily fertilised that it retained only a pale shadow of its former diversity. Lying on the boundary between pastoral farming to the west and mixed farming to the east (Vickery et al., 2001), the Lower Wye felt these pressures, but grassland losses were not quite as severe as elsewhere in southern Britain.

Fortunately, the rugged topography, small-scale field pattern, the local prevalence of smallholders and amateur landowners, and the above-average survival of small, pastoral farms afforded some protection. Even so, the ‘phase 1’ surveys by the Nature Conservancy Council (1978-91) located only 30oha of semi-natural grassland in the 36,700ha of armland and small fields in the Herefordshire part of the Lower Wye, and 700ha in the 21,900ha of the Monmouthshire part. They certainly missed some – indeed, in 2001 the Herefordshire Nature Trust found 269ha of such grassland on the Woolhope Dome – but, combining all sources, I estimate that no more than 3,000ha of grassland in the Lower Wye can now be classified as semi-natural.

Today’s grassland can be divided into two main kinds, which need some explanation. Most is sown grasslands, or leys, consisting of rye-grass cultivars and an admixture of weeds, such as dandelion and docks. These have been sown after land has been ploughed and fertilised, and will be retained for a few years for pasture and silage, and then renewed. They are widespread in the Herefordshire lowlands and the plateaus of Trellech and the Dean fringes, where they form an integral part of modern farming. The minority is ‘semi-natural’ or native grassland, made up of mixtures of native grasses and herbs. Some of the latter are readily recognised in spring and early summer as herb-rich pastures and meadows, or ‘flowery fields’: these, the remnants of traditional farming, are the principal subject of this chapter.

In reality, the distinction between modern leys and traditional semi-natural grassland is obscured by intermediate conditions. Leys gradually accumulate ‘weeds’. If, instead of reseeding after a few years, a ley is retained without further applications of fertiliser, some of the species of semi-natural grassland creep back from field margins and nearby fields. Equally, the diversity of traditional semi-natural grassland can be reduced if sheep graze throughout early summer, or if the productivity is increased by draining, liming, herbiciding and fertilising. In agricultural terms, these are ‘improved’ grasslands: they still have native grass species, but they look like short-term leys. The degree of ‘improvement’ varies from one field to the next, so in practice we can find a full range of conditions, from traditional, semi-natural grasslands without a trace of ‘improvement’ to native grasslands looking every bit as uniform and productive as sown grassland. ‘Improvement’ of a kind was also part of traditional agriculture: for example, Rudge (1813) reports that thistles and docks were weeded from pasture, together with yellow-rattle, ‘crazeys’ (lesser celandine and meadow, creeping and bulbous buttercups) and several other flowers that we now regard as attractive and desirable.

Another necessary distinction has already been drawn between meadows and pastures. Meadows are grasslands that are allowed to grow in spring and early summer without grazing, then cut for hay in June or July (Fig. 94), after which the regrowth, or ‘aftermath’, is usually grazed. Pastures are grasslands that are not cut for hay and may be grazed throughout the growing season, usually by cattle, sheep or horses, but occasionally by goats, donkeys, geese or ostriches. Both meadows and pastures are grazed after midsummer. Confusingly, intermediate treatments are legion. Grazing animals may be kept late in spring on fields that are subsequently mown. More often, fields may be allowed to grow like meadows in early summer, but then turned over directly to pasture. Then again, fields may be lightly grazed through the growing season, but topped sometime in winter to reduce the accumulation of unpalatable grass litter. What’s more, a grassy field may be a meadow one year and pasture the next.

Only residents born before 1939 will remember that most of the grassland on Lower Wye farms was semi-natural. Today, substantial areas of grass remain, but most has been ‘improved’ or sown – still grassland in scenic terms, but ecologically part of the ploughed land. Most flower-rich grassland survives in small fields owned by people whose standard of living does not depend on the land, concentrated in villages, on woodland margins and in former squatter settlements, especially on steep and irregular ground near the gorge and the edge of the Trellech plateau and Woolhope Dome. The most extensive remain on commons, such as Broadmoor Common, Coppet Hill, Ewyas Harold Common and Garway Hill. With few exceptions, semi-natural grassland lies outside modern farming.

WILD PLANTS OF CULTIVATED GROUND

Land has been cultivated in the Lower Wye for five millennia. The extent and distribution of cultivated ground has changed, but some locations are so fertile, tractable and well-drained that they may have been cropped almost continuously. One example of change comes from Howell (1943), who used farms stretching from Tintern and St Arvans across to Caerwent to compare conditions in 1751/61 and 1933. Whereas 35-45% of the land was cultivated in the mid eighteenth century, most of the arable had become permanent grass by 1933, yet most of the arable remaining in 1933 had probably been continuously cultivated since 1751, and several smaller fields had been enlarged and merged, thereby enabling small patches of rough grazing to be brought into cultivation. The sum of such individual changes has generated very wide fluctuations in recent times. Thus, in 1866 some 81,205 acres of Monmouthshire was cultivated, but by 1938 this area had declined by 74% to 20,967 acres (Clarke, 1943), and in Herefordshire, there was a 46% decline over the same period (Broughton, 1941).

Since 1938, this decline has been more than reversed in both counties. Arable has expanded so much since World War II that woods have been cleared and the once-permanent floodplain meadows have been ploughed. The main crops are now wheat, barley, sugar beet, peas, turnips, maize and rape (Fig. 95), with potatoes on the floodplain and fresh fruit under polytunnels.

Prehistoric farming allowed weeds of cultivation to develop. Some originated in naturally disturbed ground, such as riparian shoals, woodland clearings and molehills in grassland. Others thrived in the bare landscape left after the glaciers retreated and survived in mountain refuges. Yet others moved north from the more open vegetation of southern Europe, brought in some cases by immigrant people as fodder plants. By Roman times the weed flora was diverse. Burnt grain and associated organic matter found in the remains of a timber hut dating from AD 80-130 that stood outside the Roman legionary fortress of Isca (Caerleon) showed that the main crop was probably rye, supplemented by six-rowed barley, spelt, possibly bread wheat, lentils and broad beans (Helbaek, 1964). Growing with these was a miscellaneous collection of wild-oat, rye brome, perennial rye-grass, black-bindweed, curled dock, wild radish and corncockle, together with an array of wild legumes, including smooth tare, hairy tare, common vetch, yellow vetchling and grass vetchling. We cannot tell how typical these were, but they show that familiar farmland weeds were present 2,000 years ago, and suggest

FIG 95. It is worth reminding ourselves that arable fields, leys and improved pastures form the majority of the land in the Lower Wye. This field of rape is on the Dean plateau near Hewelsfield. Today, such crops contain very few arable weed species.

that cultivated ground was populated by a diverse mixture of crops, former crops, native weeds, and species, such as the vetchlings, that were probably brought here from southern Europe.

An early nineteenth-century list of arable weeds for Gloucestershire (Rudge, 1813) unfortunately gives little specific detail for ‘the forest district’, but shows clearly that the arable flora depended on the crop and the soil type. Thus, corn chamomile was abundant after peas and greater dodder followed beans and vetches. ‘Corn weeds’ included common poppy on light soils, field horsetail on moist soils, corn buttercup on clays and loams, redshank and common couch on clays, cornflower on poor soils, and common chickweed on good soil, while charlock and cleavers grew on all soils. In Herefordshire in the later nineteenth century, the seasonal colour of cultivated ground must have been something to behold, for, among the numerous arable weeds, corncockle, common poppy and red dead-nettle were very common, corn marigold was ‘locally plentiful’, corn buttercup was common on heavy soils, cornflower was common about Ross and Brockhampton, and the blue form of scarlet pimpernel was common near Monmouth (Purchas & Ley, 1889).

There is no reason to think that the weed flora was constant, or that it developed steadily. Arable land is fertile, dry and constantly disturbed. In order to survive, wild plants must be quick on their feet, germinate with the crop and produce seed before the crop is harvested and the ground is again ploughed. Most are annuals that grow rapidly, produce copious seed, disperse effectively over long distances, and/or survive as dormant seed in the soil for decades. These traits create highly mobile populations, capable of rapid increase when conditions are suitable, but rapid elimination – or obscurity as dormant seeds – when they are not.

A fine example of great changes was recounted by Bannister (1948), who recorded the botanical changes that accompanied the ploughing of grassland during and just after World War II. His observations were made at Fiddington in the Vale of Gloucester on land that is now cut by the M5 motorway, so the detail may not apply to the Lower Wye, but the scale and character of the changes must have been general. As the plants of pasture decreased, so the plants of arable and disturbed ground burgeoned. Many that were already present (e.g. charlock, scarlet pimpernel, field forget-me-not, knotgrass, dwarf spurge and black-grass) ‘increased enormously and considerably extended their area’. Some of those that appeared for the first time during the war, notably corn buttercup, wild radish, field penny-cress and many-seeded goosefoot, became very abundant or at least widespread. Other newly recorded species included the colourful corncockle and corn marigold.

Today, every effort has been made to minimise arable weeds by herbicides, early cultivation and clean seed sources, and this has devastated the arable weed flora nationally. The scale of change in the Lower Wye can be gauged from the records of Shoolbred (1920) and the modern records of Trevor Evans (Chapter 9). Several species Shoolbred knew within about 15km of Chepstow have vanished, including some once fairly common species, such as corn buttercup, corncockle, shepherd’s-needle, corn marigold, cornflower and possibly dwarf spurge, and the New Atlas (Preston et al., 2002) shows that other arable weeds have not been seen in the Lower Wye since 1970, including pheasant’s-eye, thorow-wax and broad-leaved spurge. Many species that persist have been greatly reduced, including common poppy, long-headed poppy, fool’s parsley, black-bindweed, field pepperwort, field woundwort and black-grass. Some remain, however: for example, in 2004 I recorded common orache, lesser swine-cress, sun spurge, common fumitory, black-bindweed, hedge mustard, scentless mayweed and common field-speedwell on the margins of a beet field at Huntsham.

NEUTRAL GRASSLAND

Despite the huge losses of semi-natural grassland over the last 60 years, there is still enough to appreciate the variety that was once common. Some 24 of the grassland communities recognised in the National Vegetation Classification (Rodwell, 1991b, 1992) may survive within the Lower Wye, but none is common (Table 10). Here I simply gather what remains into six broader types: the first three occupy ‘dry’ ground, the fourth forms on poorly drained sites, and the final two are subject to inundation by fresh and salt water respectively. Some of the communities are really heaths, marshes and salt marshes, which are considered separately.

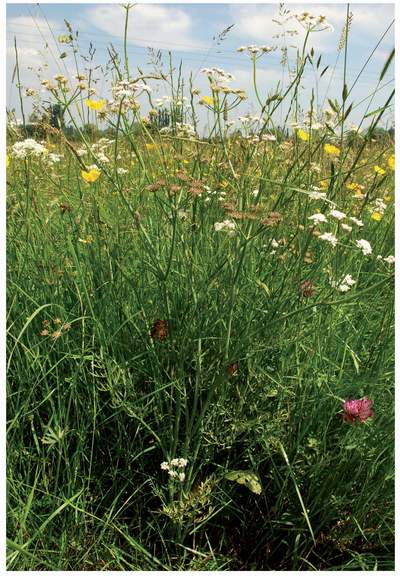

Mesic or ‘middle-of-the-range’ grassland is commonly described as ‘neutral’, but it ranges from almost-calcareous to strongly acid. Until the 1930s, it must have been the most abundant and widespread of all types of semi-natural vegetation in the region, and it is still by far the commonest type of semi-natural grassland. Characteristically, it is dominated by sweet vernal-grass, crested dog’s-tail, meadow foxtail, timothy, soft-brome, common bent, red fescue, Yorkshire-fog, perennial rye-grass, cock’s-foot, occasional quaking-grass, and a good deal of the grass-like field wood-rush. Until late June, these are visually dominated by an array of flowering herbs.

Neutral grassland comprises several reasonably distinct communities, most of which include meadow buttercup, common mouse-ear, cat’s-ear, rough

TABLE 10. The grassland, marsh and heathland types recognised in and around the Lower Wye Valley, expressed in terms of the National Vegetation Classification. Full descriptions of each community are given by Rodwell (1991b, 1992). Sources include various surveys carried out by the Wildlife Trusts, Countryside Council for Wales and English Nature (Mockeridge et al., 1995; Regini, 1995; Doe, 1996; Wilson, 2003; and others).

GRASSLAND COMMUNITY

CALCAREOUS GRASSLAND

CG1 Festuca ovina – Carlina vulgaris grassland

CG2 Festuca ovina – Avenula pratensis grassland

CG3 Bromus erectus grassland

CG7 Festuca ovina – Hieracium pilosella – Thymus praecox/pulegioides grassland

CG10 Festuca ovina – Agrostis capillaris – Thymus praecox grassland

ACID GRASSLAND

U1 Festuca ovina – Agrostis capillaris – Rumexacetosella grassland

U4 Festuca ovina – Agrostis capillaris – Galium saxatile grassland

U5 Nardus stricta – Galium saxatile grassland

U20 Pteridium aquilinum – Galium saxatile community

NEUTRAL (MESIC) GRASSLAND

MG1 Arrhenatherum elatius grassland

MG5 Cynosurus cristatus – Centaurea nigra grassland

MG6 Lolium perenne – Cynosurus cristatus grassland

MG9 Holcus lanatus – Deschampsia cespitosa grassland

MG10 Holcus lanatus – Juncus effusus rush pasture

ALLUVIAL GRASSLAND

MG4 Alopecurus pratensis – Sanguisorba officinalis grassland

MARSH

M6 Carex echinata – Sphagnum recurvum/auriculatum mire

M22 Juncus subnodulosus – Cirsium palustre fen-meadow

M23b Juncus effusus/acutiflorus – Galium palustre scrub

M24 Molinia caerulea – Cirsium dissectum fen-meadow

M25 Molinia caerulea – Potentilla erecta mire

M27 Filipendula ulmaria – Angelica sylvestris mire

BRACKISH GRASSLAND

MG11 Festuca rubra – Agrostis stolonifera – Potentilla anserina grassland

MG12 Festuca arundinacea grassland

MG13 Agrostis stolonifera – Alopecurus geniculatus grassland

hawkbit, oxeye daisy, common bird’s-foot-trefoil, red and white clover, ribwort plantain and common sorrel. Most falls within type MG5, which, even in winter, can usually be identified by the dead heads of knapweed. The typical rush-pasture of the Severnside flats and poorly drained ground and permanently moist depressions elsewhere falls within MG10, and is characterised by the presence of creeping bent, Yorkshire-fog, soft-rush and creeping buttercup. Hollows on heavy soils generate the species-poor MG9 grassland, characterised by tussocks of the tough tufted hair-grass, whose leaves cut the hands like razors. Those MG5 grasslands that have been improved become type MG6, which has more rye-grass and fewer flowers. When it is fertilised, neglected or mown without removal of the clippings, MG5 grassland changes into a thick growth of false oat-grass and cock’s-foot (MG1). Similar grassland can be recognised on waste ground, rubbish dumps, roadside verges, urban grassland and amenity ground, where the tussocky grasses often grow with an admixture of equally vigorous cow parsley, hogweed and nettle.

Many distinctive but infrequent species are associated with these grasslands. Yellow-rattle is common in meadows. Some examples have concentrations of common spotted-orchid and occasionally some other orchids, such as greater butterfly-orchid, twayblade, early-purple orchid and green-winged orchid. The more acid examples have heath spotted-orchid: in one meadow at Tidenham Chase, the geological line between Tintern Sandstone and Carboniferous Limestone is faithfully marked by the segregation of the two spotted-orchid species. Careful searching may reveal the tiny ferns, adder’s-tongue and, very rarely, moonwort. Occasionally, the miniature ‘broom’, dyer’s greenweed, is found, and this is quite common at Springdale Farm. Many examples have a scatter of devil’s-bit scabious and the more base-rich examples may have fairy flax. Dulas Church was rebuilt in a meadow, and its churchyard still contains cowslips, daffodils, spotted-orchids and occasional greater butterfly-orchids. In the headwaters of the Monnow and the Escley Brook, and in a marshy part of the middle Wye Valley known as The Flits, globeflower, common bistort and lady’s-mantle bring a touch of the Pennine Dales hay-meadows to the Lower Wye.

Hudnalls

The intimate detail of neutral grasslands and how they respond to management can be illustrated by the ‘flowery fields’ of the Hudnalls (Peterken, 2005b) (Fig. 96), a wooded common until 1800 when it was enclosed by squatters into a mass of tiny fields, many no more than o.5ha in extent. Before enclosure, the common must once have been fairly heathy, for bilberry can still be found in

FIG 96. A hay meadow in the Hudnalls, with Oakhill Wood and Madgetts Farm beyond. Several of the characteristic constituents of this MG5 grassland are common, including yellow-rattle, sheep’s sorrel and a dwarf form of hogweed, among herbage dominated by sweet vernal-grass.

several hedges, but 200 years of mowing, grazing and intermittent cultivation have changed it into MG5 grassland and eliminated cross-leaved heath and other calcifuge species.

The common and widespread herbs start with an early display of cuckooflower, then the colour changes to yellow with meadow buttercup, common bird’s-foot-trefoil, cat’s-ear, meadow vetchling, rough hawkbit, dandelion and imperforate St John’s-wort. In addition, yellow-rattle has been recorded from about 40 meadows, sometimes in great abundance. Purples are well represented by common spotted-orchid, knapweed and several less conspicuous species, such as selfheal, thyme-leaved speedwell, common vetch and red clover, before common sorrel develops tall reddish inflorescences just before cutting. White flowers are represented by oxeye daisy, white clover and lesser stitchwort, and there is even a miniature form of hogweed. The mixture changes in depressions and seepages, where the tussocks of soft-rush are conspicuous throughout the year, and bugle, angelica, marsh thistle, yellow iris, ragged-robin, corn mint, common fleabane, lesser spearwort, creeping buttercup, common marsh-bedstraw and silverweed add colour during the season. On light soils pignut, common mouse-ear, tormentil, heath spotted-orchid and harebell add a touch of heathland.

It is the inconsistent and generally rare species that give some fields their botanical individuality, such as twayblade, adder’s-tongue, common milkwort, bitter-vetch, lady’s-mantle, dyer’s greenweed, lousewort, heath-grass, green-ribbed sedge and pale sedge. On dry, base-rich margins, one finds primrose and sometimes small sedge meadows with glaucous, common, oval and yellow sedges. One field developed a carpet of eyebright one summer in the early 1990s, but these delicate pale-purple flowers then vanished until 2003, when the ground was temporarily turned over by Gloucester blackspot pigs. To local delight, one meadow supports a small population of green-winged orchids (and that within 20m of a barn with a colony of lesser horseshoe bats!), but the same meadow once also contained autumn lady’s-tresses, which is now unknown locally. Meadow saffron once grew in the meadows near Hewelsfield ‘with great luxuriance’ (Rudge, 1803), and it can still be found near Rodmore Mill. With the exception of the lousewort, which is associated with acid flushes, there is no obvious feature of their sites that explains why each species is present, or indeed why it is not more widespread.

Both the structure and composition of the grasslands are influenced by management. When meadows are changed to pasture, grasses, rushes, sedges and low-growing herbs such as daisy, selfheal and hawkbit prosper, but oxeye daisy, hogweed and other tall, broadleaved herbs suffer. Yellow-rattle usually disappears, because it is an annual without a bank of long-lived, dormant seeds in the soil: it must shed seed each year to survive, and if all flowers are grazed off before they can seed, the species dies out. When cattle are let into fields in June, they seem to make a beeline for the spotted-orchids, but their impact is mitigated by their habit of not grazing close to cowpats, leaving tufts of grass and flowers that function as micro-meadows. Sheep, on the other hand, graze almost everything except nettles and thistles, thereby generating an even, close-cropped turf in which pignut and germander speedwell, but few other herbs, survive. Horses leave a richer turf, but they easily poach the ground, concentrate their activities in latrines and let in broad-leaved docks, creeping thistle and spear thistle.

Changes in management have a major impact. Liming changes the soil, herbicides remove forbs, and fertiliser encourages the growth of a few vigorous species to the detriment of the many less vigorous species. These ‘improved’ fields still have sweet vernal-grass and dog’s-tail, and they tend to develop a fine display of buttercups, but they are otherwise much less diverse. Neglect, on the other hand, allows grassland to develop towards woodland. Initially, neglected fields grow like meadows, but by the end of the second growing season the grass is tussocky, bracken and bramble have spread from the hedges, a few oak, sycamore and other tree seedlings have become established, and the long blackthorn roots have sent up strong shoots. Since some species of bramble can run up to 8m through uncut, ungrazed late-summer grass, very few years of neglect are needed to turn a 0.5ha field into scrub, and thence into woodland. Surprisingly, some abandoned fields fail to become woodland, but develop into thickets of cock’s-foot, bracken or bramble. Such ground develops a woodland ground vegetation of bluebell and wood anemone, sparing only a few sheep’s-sorrel and cowslip as scant reminders of the former meadow.

In practice, fields in the Hudnalls are rarely abandoned completely. Rather, they are grazed intermittently, usually when the owner hires some ponies from the local horse sanctuary, or finds someone to run some sheep for a few weeks. Under this non-intensive management, fields can develop a pleasing mosaic of grassland, scrub, bracken and scattered trees, most of the meadow flora survives, but woodland species move out from the hedges to form quite stunning displays of bluebells and anemones (Fig. 97). Wood sage, bitter-vetch, twayblade, betony and barren strawberry occur in grassland, but mostly near the woodland edge.

FIG 97. MG5 grassland in the Hudnalls into which bluebell has spread under cover of advancing bracken. This field is under-used, but it is the only one locally in which dyer’s greenweed has survived.

New Grove Meadows and Pentwyn Farm

These meadows must be the best in the Lower Wye, but they also demonstrate how ‘improvement’ causes a loss of diversity. Until the 1940s, they would not have been exceptional, just ordinary fields on the Trellech plateau and the fringes of the Wye gorge, but they were not ploughed and fertilised, and now they are protected as Gwent Trust reserves. Pentwyn shelters among thick hedges containing giant lime pollards, but New Grove enjoys views over the Trothy valley to the Black Mountains that are simply stunning when seen over the carpet of orchids.

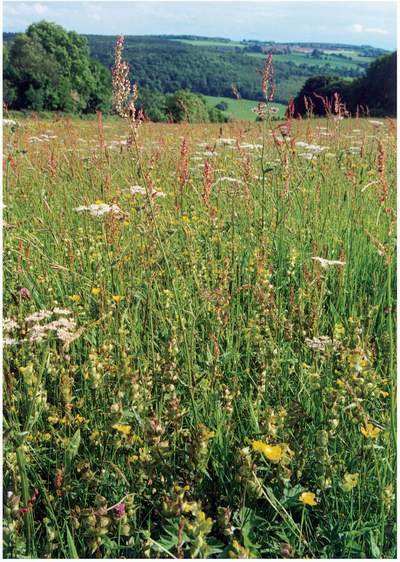

Both reserves are fine examples of neutral (pH 5) grassland on well-drained loams. The principal grasses are sweet vernal-grass, red fescue, common bent, crested dog’s-tail and depauperate Yorkshire-fog, with a fringe of cock’s-foot and tall Yorkshire-fog growing among the bracken and bramble that is always trying to invade from the hedges. Knapweed, oxeye daisy, common bird’s-foot-trefoil, selfheal, ribwort plantain and a mixture of common and heath milkworts occur commonly among the grasses, and yellow-rattle is distributed evenly and abundantly throughout the sward. New Grove has several species commonly associated with alkaline soils, notably quaking-grass, cowslip, glaucous sedge, spring-sedge, rough hawkbit, adder’s-tongue and dyer’s greenweed. Locally, however, the soil must be acid, for heath-grass and tormentil occur patchily. Common sorrel is far less frequent than it is in the Hudnalls.

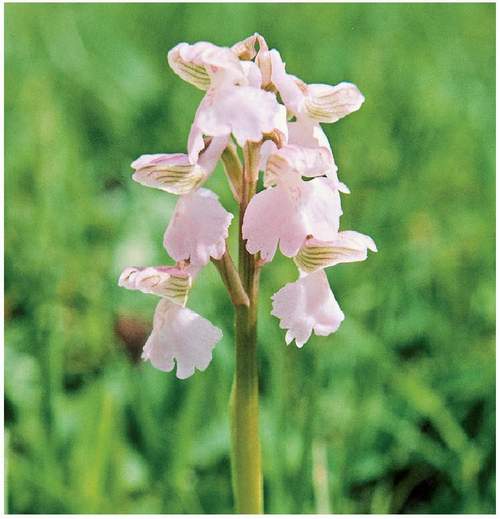

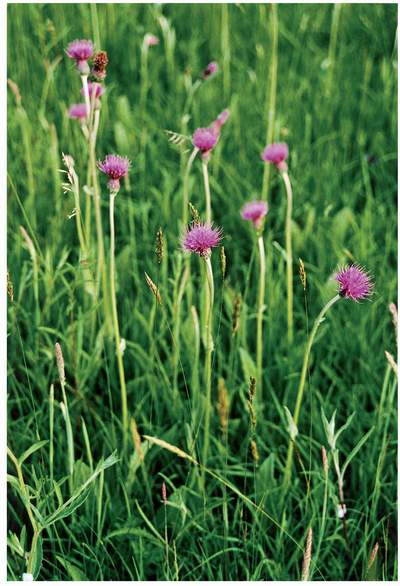

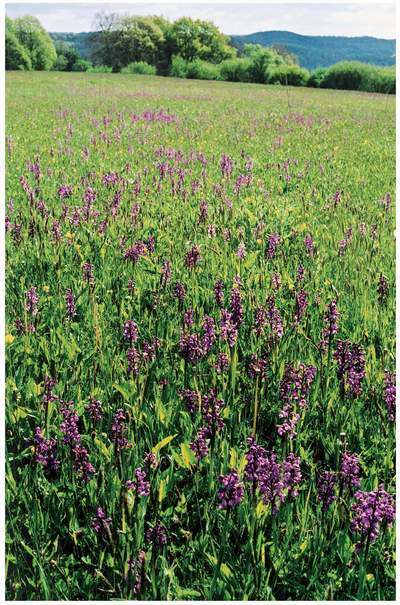

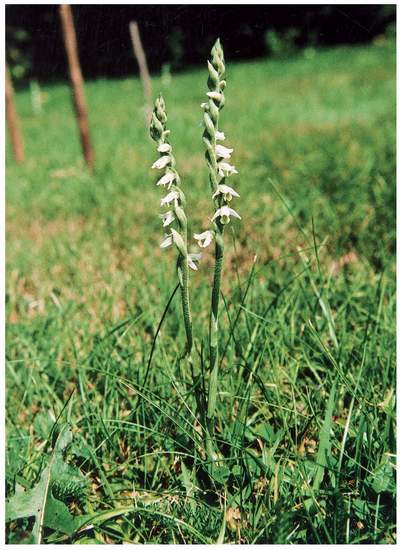

The species that really command attention are the orchids. The early season is coloured by early-purple orchids and several thousand green-winged orchids, standing out as dark purple spikes (with a few pale variants) from the short turf (Figs 98 & 99). Later at New Grove, just as the yellow-rattle is going to seed, thousands of common spotted-orchid form a light purple carpet (Fig. 100), among which groups of southern marsh-orchid stand out as larger and darker spikes. Close inspection reveals many twayblades, but these green orchids are

FIG 98. Green-winged orchids in the Pentwyn Farm reserve, saved from the plough by the Gwent Wildlife Trust. The orchids are spreading into adjacent fields, where improved grassland is being treated as part of the reserve.

FIG 99. Most of the green-winged orchids are dark purple (Fig. 98), but a few are magenta, and rare individuals are white.

FIG 100. Common spotted-orchids in New Grove meadow, against a panorama west over the Usk valley to the Sugar Loaf. Before the hay cut, this field runs through a succession of orchid displays, from green-winged and early-purples to spotted and marsh orchids, with the less conspicuous twayblades mixed in. Such fields were probably common until the 1930s.

almost lost among the grass. At Pentwyn, the spotted-orchids are common, but never quite achieve a sweep of colour by themselves. The prize here is the population of greater butterfly-orchid, growing as an integral part of the meadow. After a decade of Trust management, their numbers have increased tenfold from an initial flowering population of 15 spikes.

Although sympathetic neighbours maintain equally rich fields next to both reserves, the flower-rich fields are islands in the sense that surrounding fields are all intensively farmed. They are the residue of a much larger spread of flowery fields, including more fine green-winged orchid meadows that in the last decade or so have either been improved or obliterated under houses and gardens. However, both reserves have been enlarged by adding adjacent fields that supported semi-natural grassland (MG5) until recently, but which now contain semi-improved grassland (MG6).

A comparison of the ‘improved’ fields with the surviving semi-natural fields enabled Jan Winder and Jerry Tallowin to measure how improvement had changed the composition. Some ubiquitous species, such as sweet vernal-grass and common bent, had not been affected, but 25 species had gone, including common species (e.g. red fescue, common spotted-orchid, spring-sedge, selfheal, cowslip) and local species, notably adder’s-tongue, green-winged orchid and greater butterfly-orchid, while other common species were much reduced (e.g. oxeye daisy, rough hawkbit, yellow-rattle, knapweed and common bird’s-foot-trefoil). On the other hand, several already-common species, such as rough meadow-grass, creeping thistle, perennial rye-grass, dandelion, creeping buttercup and meadow buttercup, evidently increased with ‘improvement’, and a few species must have colonised. Overall, agricultural improvement reduced species-count from 58 in the semi-natural field to 50 in the semi-improved field, evicted some sensitive and colourful species, altered the relative abundance of grass species, and promoted buttercups, dandelions and thistles.

Elsewhere in the Lower Wye a scatter of good neutral grasslands remains on the Woolhope Dome, the northern Dean from Lydbrook through English Bicknor and Staunton to Newland. The Woodland Trust is restoring some neglected examples below Highbury Wood. On several commons in Herefordshire, rich neutral grassland is still cut for hay, notably Checkley Common on the northern fringes of the Woolhope Dome (which has a particularly orchid-rich flora), Broadmoor Common (close to Haugh Wood), the village green at Garway (diversified with wet depressions and a fragment of heathland), Merryhurst Green (where quaking-grass is locally dominant) and the somewhat neglected Honeymoor and Littlemarsh Commons. On the western fringes of the Lower Wye, the Hereford Nature Trust protects fine meadows at The Sturts (wet enough to include narrow-leaved water-dropwort), along the Escley Brook (where meadow saxifrage survives) and at Crow meadow (where there is a fine example of a meadow restored with green hay). Immediately north of Haugh Wood, Plantlife has an extensive meadow at Joneshill Farm. Hidden among lime-ash woodland at Ridley Bottom (Tidenham), the Gloucesterhire Wildlife Trust has an amazingly rich meadow whose flora ranges from salad burnet to tormentil, and at Clarke’s Pool Meadows to the east of Lydney it maintains perhaps the only traditional hay meadow left on Severnside, replete with green-winged orchids and adder’s-tongue.

OTHER TYPES OF SEMI-NATURAL GRASSLAND

Calcareous grassland

With so much limestone in the Lower Wye, one might expect to find a good deal of calcareous grassland, but most of the crags are occupied by ancient woodland, the slopes below are often flushed, most of the limestone plateaus and gentler slopes are cultivated, and clusters of small fields are generally on acid soils. Cowslips, yellow oat-grass and field scabious picked out road verges on limestone, but most verges have become thickets of tall grasses, such as cock’s-foot and false oat-grass. Railway cuttings must have acquired some calcareous grassland, but they have become overgrown in the last 40 years and the motorway cuttings are following suit (Chapter 8). Calcareous grassland fragments also developed in and around quarries, but, if not already wooded, abandoned quarries are vulnerable to natural invasion by scrub-woodland and well-meant tree planting.

Calcareous grassland was not always so limited. Old county Floras record that common rock-rose, greater knapweed, small scabious, saw-wort and downy oat-grass were all common on at least parts of the limestone, that bee orchids and autumn gentians were thinly but widely scattered, and that frog orchid, pyramidal orchid, soft-leaved sedge and crested hair-grass grew in several places around Tidenham, but these have all been much reduced or extinguished. There were also rarities, such as the fly orchid in pasture at Symonds Yat, mountain everlasting on the Doward and wild liquorice near Woolhope.

Today, the most interesting remnants are the small patches of grassland on the Seven Sisters rocks, described above. Elsewhere around the upper gorge one can still find patches of turf with common rock-rose, salad burnet, field scabious, harebell and restharrow, with yellow-wort and blue fleabane in old quarries, and small scabious cowering beneath the walking boots on the Symonds Yat viewpoint. Calcareous grassland with bee and pyramidal orchids is developing below the motorway on Dixton Bank. Likewise, on the Woolhope Dome limestones, scrubby grassland is maintained on Common Hill containing quaking-grass, common rock-rose, wild thyme, milkwort and marjoram, and the component species grow scattered on lane verges and quarry fringes. Near Winslow Mill, small patches of grassland within woodland contain wild liquorice, autumn gentian and several orchid species. A reserve at Wessington Warren has autumn lady’s-tresses and dwarf thistle, but much has been planted with trees.

Several small remnants of CG3 and CG10 occur on the Dean plateau around Clearwell, Whitecliff and Tidenham. These usually take the form of neglected grassland dominated by upright brome in which the limestone grassland flowers are few and far between, but a small example survives at Ashberry House as a lawn with abundant green-winged orchids. On the Dean fringes, a dry bank near Ellwood Green that is maintained by commonable sheep has dwarf thistle, autumn lady’s-tresses, fairy flax and wild thyme.

In Monmouthshire, there were once fine grasslands near the Minnets, Mounton and Chepstow, but the best remnant seems to be Brockwell Meadows near Caerwent, where quaking-grass, yellow oat-grass, sheep’s-fescue and other grasses mix with dwarf thistle, wild thyme, salad burnet and a scatter of autumn lady’s-tresses, green-winged orchid and pyramidal orchid. Nearby, more grassland is guarded within RAF Caerwent. Again, fragments of remembered grassland survive, sometimes as garden lawns (Chapter 11). On the coast, an embankment at Sudbrook Point has steep south-facing slopes with common rock-rose, salad burnet, wild thyme, restharrow and, surprisingly, narrow-leaved everlasting-pea.

Acid grassland

These heathy grasslands lie at the other end of the spectrum of dry grassland. They must once have been frequent as components of heathland on the commons of the sandstone country, but the great majority have been ‘improved’ within the last 200 years. Fragments survive on the fringes of rides in plantations and the margins of Cleddon bog, but the type has all but disappeared from farmland. Some has been transformed into mesic grassland by liming, fertilising and intermittent cultivation, leaving some constituents of the former grass-heaths, such as bilberry and slender St John’s-wort, clinging to marginal banks.

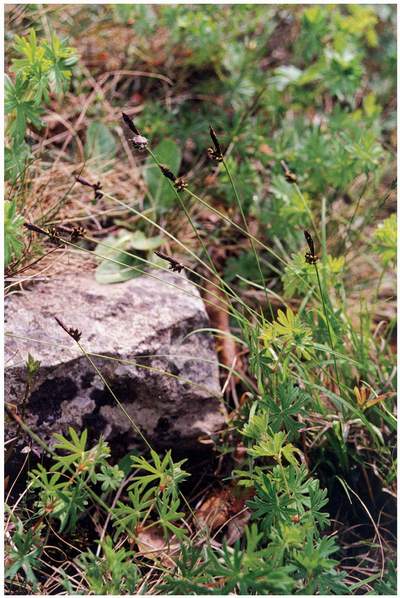

The largest surviving patches are the remaining unenclosed commons of Coppet Hill, Staunton Meend, Poors Allotment, Gray Hill, Ewyas Harold, Garway Hill and Merbach Hill, but in all of these the reduction in common pasturage has allowed scrub to colonise most of the ground. Where they have not changed into birch, oak, hawthorn, sallow, sycamore or ash woodland, most have developed into thickets of gorse, bracken or bramble, leaving remnants of grassland along tracks. At Merbach Hill, for example, just 2% of the ground remains open, but at Coppet Hill a community group is reclaiming some of the grassland from bracken and bramble, and at Poors Allotment the managers have arrested further encroachment by scrub cutting and grazing. Small patches of acid grassland survive in fields on the Trellech plateau at Llanishen and Cobblers Plain. One of the best is a slope with conspicuously abundant ant mounds next to Buckholt Wood near Monmouth (Fig. 101).

These grass-heaths characteristically have heath bedstraw, tormentil and specialised sedges, such as pill sedge, among the fine-bladed grasses. At Buckholt, the principal grasses are red fescue and sheep’s-fescue, with common bent, heath-grass, quaking-grass and sweet vernal-grass, and large thyme covers the ant hills. On both Merbach Hill and Ewyas Harold Common, the fortunate walker can find meadow saffron in late summer. On moist, base-poor ground in the Dean patches of mat-grass form outliers of a community that mostly grows on peaty soils in the uplands of north and west Britain.

FIG 101. Ant hills in a patch of acid grassland near Hayes Coppice, north of Monmouth. Ant mounds were levelled by hay cutting and regularly harrowed out of pastures, and they remain uncommon today, even in semi-natural grassland, but this field on a dry, southwest-facing slope is a conspicuous exception.

Alluvial grassland

Most grassland on floodplains is mesic grassland with a distinctive composition, growing on well-drained but regularly inundated, highly fertile soils, and it was traditionally cut for hay and grazed in summer by cattle. Such meadows were once characteristic of the whole valley and its main tributaries, especially the Lugg, and gave rise to particular forms of meadow management under common rights, known as Lammas meadows (see below). These meadows were permanent – flooding used to prevent cultivation – but the majority have now been ploughed and/or reseeded. Nevertheless, fine examples survive in the keeping of the Herefordshire Nature Trust at Hampton, Letton Lake and, within sight of their headquarters, by the Lugg. Botanically, they fall within MG4 grassland, which is distinguished from MG5 by the presence of tall herbs, such as meadowsweet and great burnet, much less sweet vernal-grass and field wood-rush, but more meadow foxtail, common mouse-ear, Yorkshire-fog and meadow buttercup. The Wye-Lugg floodplains seem to have a distinctive variant of MG4 characterised by the presence of narrow-leaved water-dropwort.

The Wye was lined by meadows. As one tour guide claimed, ‘the meads we traverse [near Bigsweir] are rendered extremely cheerful nearly the whole of the way by the jolly mowers and their attendant companions, in the hay season’ (Heath, 1806). Less flatteringly, Hassell (1812) noted that ‘the lands about the Wye and Monnow rivers, are rich meadows, wherever they lie low enough to receive the overflowings of these rivers, whose waters bring down the rich mucilaginous mud of Herefordshire.’ Most have gone and the remnants are pasture. Alluvial grasslands at Sellack and Backney commons, Dixton, opposite Llandogo and along the Monnow and smaller tributaries seem to be semi-improved, and in narrow valleys they form part of a larger field without distinctive management. Dry and well drained when not flooded, many have abundant pignut.

The best examples, the now-famous Lugg Meadows, are among the finest examples of floodplain grassland remaining in Britain (Brian & Thomson, 2002). They are the largest survival in Britain of Lammas meadows, a medieval and earlier form of management whereby the owners took a crop of hay while stock were excluded from 3 February to 31 July and the commoners depastured their stock on the land for the other six months. The fields were divided into strips, and the owners drew lots to decide which strips they would own in any particular year, i.e. these places were ‘lot meadows’. In Herefordshire the Lammas meadows were particularly common on, but not confined to, the Lugg and the middle Wye. Anthea Brian has found evidence of 59 Herefordshire Lammas meadows surviving as late as the eighteenth century (Brian, 2000; Brian & Thomson, 2002), but today only Lugg Meadows, Hampton Bishop Meadows and meadows upriver at Letton Lake survive, all incomplete and all held by the Herefordshire Nature Trust.

The Lugg Meadows lie between the Lugg itself and a narrow backwater known as the Lugg Rhea on free-draining gravel deposited by the river. They form a huge unbroken sweep of grassland that assumes a curious grey-pink-yellow colour in June, when the abundant buttercups mix with the tall grass heads. The principal constituents are sweet vernal-grass, meadow fescue, soft-brome, crested dog’s-tail, meadow foxtail, timothy, meadow barley, rough and smooth meadow-grasses and perennial rye-grass, with an admixture of knapweed, cuckooflower, oxeye daisy, yellow-rattle, common sorrel, and meadow, creeping and bulbous buttercups. These species are frequent in meadows elsewhere, but the Lammas grasslands are set apart by their lush growth, the presence of some specialist floodplain species, and the absence of many low-growing species. The specialists are best seen before the grass grows to its full luxuriance. First up is the fritillary, which here is remarkable for the dominance of white forms over the more familiar patterned purple colours (Fig. 102). Later, the umbellifers pepper-saxifrage and narrow-leaved water-dropwort (Fig. 103) grow above the grasses. All three have become nationally rare with the general destruction of native grassland by modern agriculture. Several other interesting species occur locally, including meadow crane’s-bill, great burnet, several

FIG 102. Fritillaries in Lugg Meadow. Unusually, white forms are always in the majority of this population, though a few purple, chequered forms are present.

FIG 103. Narrow-leaved water-dropwort among the buttercups of Hampton Meadow. This species is characteristic of the surviving ancient meadows on the lower Lugg and middle Wye.

microspecies of dandelion and three species that are also at home in woodlands, meadow saffron, wood anemone and adder’s tongue.

Interesting though they are, floodplain grasslands are not species-rich. High natural fertility resulting from flooding stimulates the growth of grasses and thereby excludes the low-growing plants found in less productive grassland. Moreover, the floodplain is well drained and remarkably free of the wet hollows that enable rushes and other marsh plants to form part of the patchwork, save for some marsh-marigold and meadowsweet in wetter patches. The main source of diversity is the river and drainage channels. These bring in species such as reed canary-grass, bur-reeds and common club-rush in the channels, and common comfrey, nettles, great willowherb, yellow-cresses, tansy and silverweed along the banks and fresh alluvial deposits.

Alluvial grassland at the head of the Golden Valley has a place in Britain’s agricultural history. Here, in 1580, Richard Vaughan created one of the earliest water-meadows (Everard, 2005). Headwater streams were channelled into trenches from which water was released into a regular network of shallow ditches, from where it was gathered in drains and returned to the streams. Today, some sluices and part of the Trench Royal survives with some associated lesser channels, mainly along the Slough Brook as it heads down to Turnastone Court Farm, but little else. Despite the local tradition that the grassland has not been ploughed for 400 years, it has only common species.

Marsh grassland

Marsh grassland usually occurs as small, wet depressions in otherwise dry fields, but a few fields are essentially marshes that have been drained enough to convert them to grassland. On the Caldicot Level, Hassell (1812) recorded that the ‘grasses’ of such ‘moors’ were ‘meadow soft-grass, meadow fescue, cocksfoot grass, sweet vernal grass, foxtail grass, creeping trefoil, marsh bent and darnel’. Generally, the main constituents are sharp-flowered and soft-rushes, Yorkshire-fog, sweet vernal-grass and common herbs such as meadow buttercup, creeping buttercup, selfheal, greater bird’s-foot-trefoil and common marsh-bedstraw. Classified as M23, this assemblage is found from the Caldicot Level to the commons of Ewyas Harold and Merbach Hill, and is quite frequent in the Dean, Dean plateau and Trellech plateau.

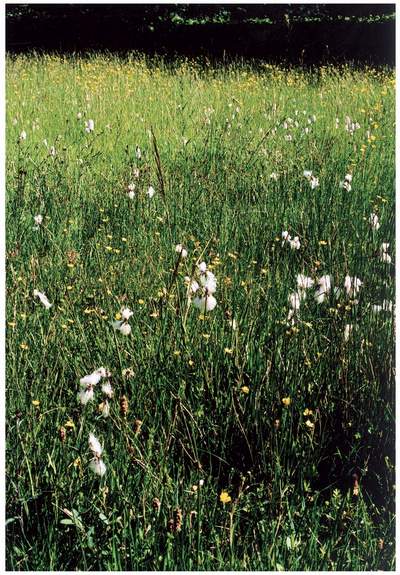

The finest extensive example, in the Magor Marsh reserve, has meadows with heath and bog species, such as purple moor-grass, carnation sedge, velvet bent, heath-grass and the colourful meadow thistle (type M24) (Fig. 104). Until recently, this was acid enough to include cottongrass, but the meadow is now more alkaline and the cottongrass has gone. Some other damp meadows in the Gwent

FIG 104. Marsh grassland treated as meadow on the Gwent Levels at Magor Marsh. This field is one of the few in which marsh thistle survives.

Levels have amphibious bistort, meadow barley and marsh horsetail, but these are seen as a variant of MG5 grassland. The last remaining great burnet meadow on the middle Wye at Letton Lake also contains globeflower, a species more associated with the upland fringes.

Brackish grassland

The tides come up the Wye as far as Bigsweir Bridge, and from this point down the riverside vegetation bears the mark of salt water. This does not immediately affect the floodplain grassland – after all, it is only inundated when the river is in spate, and then salt water is held downriver by the flood – but from Brockweir downwards the floodplain salt-tolerant species increasingly form part of alluvial grassland, and salt marsh species thrive on the muddy slopes and in saline runnels on the floodplain. Salt marsh and brackish grassland also fringe the Severn, though most of those on the Caldicot Level have been cut offby the sea wall. Surviving examples classify as the inundation types of mesic grassland, MG11, MG12 and possibly MG13.

The most extensive Severn salting, below Sedbury Cliff (Fig. 105), is mostly used as pasture. Here turf is dominated by common saltmarsh-grass and red fescue, sea aster, greater sea-spurrey, sea arrowgrass, sea-milkwort, sea plantain, buck’s-horn plantain, annual sea-blite and patches of saltmarsh rush. The top edges have patches of sea club-rush, sea couch and common reed, with scattered parsley water-dropwort. A lower zone dominated by glassworts (mainly common glasswort) is confined to creeks within the higher zones, and the edges of the mud banks have ungrazed sea aster and common cord-grass. Something like this must have been familiar to aurochs and Mesolithic people.

The long, narrow brackish grasslands along the Wye were once used as meadows. In Shoolbred’s time they contained patches of marsh with common spike-rush, sea club-rush, many sedges (including greater pond-sedge, distant

FIG 105. Sedbury Cliff and grazed salt marsh on the margins of the Severn Estuary. The cliffis largely wooded, but constant erosion keeps sections open, and seepages allow marsh and tufa deposits to develop locally. The salt marsh has not been embanked: elsewhere the upper marsh has been lost through embanking to drainage and cultivation.

sedge, common sedge, slender tufted-sedge, oval sedge and divided sedge), hemlock water-dropwort and the brackish specialist parsley water-dropwort. Today, Tallards Marsh, a broad estuarine pasture below Chepstow, still has stiff saltmarsh-grass, bulbous foxtail, marsh foxtail, marsh dandelion and slender hare’s-ear, but lesser water-parsnip, brown sedge and grey sedge have seemingly gone. Hamway, Penrin and Martridge meadows below Piercefield are scrub-covered thickets of reeds, lesser pond-sedge, hemp-agrimony and hop, fringed by sea aster and sea couch. One brackish meadow survives at Abbey Passage Farm, Tintern, where common meadow species (cock’s-foot, perennial rye-grass, meadow buttercup, false fox-sedge, red clover), coexist with localised grasses (meadow barley, tall fescue), marsh species (meadowsweet) and herbs characteristic of low-lying, periodically inundated ground (silverweed). Salt-tolerant specialists, such as sea couch and salt marsh rush, enter the grassland below Tintern.

DYNAMICS OF GRASSLAND CHANGE AND RESTORATION

Wye Valley grasslands are always changing: each year the amount of each species is different from the previous year. Some of this variation is due to weather – a wet spring or a summer drought benefits some species while disadvantaging others – but much is decided by how fields are used. Each type of grassland has meadow and pasture forms, potentially, and pastures change according to the kind of stock and the season they graze, so any change in usage forces adjustments to sward structure and composition. Changes between hay cutting and light grazing by cattle in early summer probably have only trivial effects on composition, but changes between hay and all-year-round grazing by sheep or horses are more profound.

Our own meadows are a case in point. When we arrived, the fields had been used as horse pastures for at least a decade, and only two yellow-rattle plants could be found, but five years after changing them to meadows followed by cattle, yellow-rattle had become abundant in five of the eight fields. Nevertheless, yellow-rattle remained patchy, even after a decade as meadow, and its distribution still reflected the process of colonisation. Contrast this with New Grove and Pentwyn meadows, where yellow-rattle is abundant and evenly spread, presumably because these meadows have been consistently used for many years and yellow-rattle has long been abundant. Perhaps, therefore, the patchy and inconsistent occurrence of species within and between examples of neutral grassland is partly explained by past changes in management, combined with incomplete recovery from the last change.

Many surviving examples of neutral grassland were cultivated in the mid nineteenth century, and some still exhibit unmistakable ridge-and-furrow. For example, two of our fields were used to raise strawberries and potatoes respectively less than 40 years ago, yet they are undeniably flowery meadows now, and we quickly discovered just how difficult it is to keep common sorrel, oxeye daisy, field wood-rush and knapweed out of vegetable beds next to them. Grasslands used to be reconstituted from barn sweepings, but colonisation from nearby must have contributed, for even leys ‘go back’ as native species return if they are not resown. Recovery from changes in grass use also involves buried seed, and perhaps this explains how the best meadows on the Springdale Farm reserve now have dyer’s greenweeds, even though they were used as horse-pastures for several years less than a decade ago.

Some insights into grassland recovery will emerge from Jerry Tallowin’s study at Pentwyn Farm, where he surveyed not only the visible flora, but also the population of buried seeds lying dormant in the top 10cm of the soil of both herb-rich neutral meadows and adjacent semi-improved meadows. The soil of the former had hundreds of thousands of common bent and sweet vernal-grass seeds in each square metre, with knapweed and oxeye daisy in tens of thousands per square metre, so it is hardly surprising that the sward quickly recovers after a disturbance. The semi-improved meadow had just as many common bent and sweet vernal seeds, but knapweed and oxeye daisy were absent. Instead, several arable weeds, such as scarlet pimpernel, marsh cudweed and broad-leaved dock, were present in the seed bank but not visible in the sward, waiting to spring to life immediately after disturbance. With few exceptions, the species evicted from the sward by ‘improvement’ were, like knapweed and oxeye daisy, absent from the seed bank, which explains why they take so long to reappear in leys. On the other hand, most of the species that increased during ‘improvement’ did have seed banks. In general, when semi-natural grassland is lightly and temporarily disturbed without totally eliminating the sward (e.g. by moles, badgers or poaching), it recovers quickly and may even be diversified. But, if it is ploughed, cropped and then reseeded, half the species (mostly colourful broadleaved herbs) are not only destroyed as visible plants but possess no reserve of viable seeds in the soil from which to recover, even if the field is returned to permanent grass.

Apart from exceptional fields where management has long been unchanged, such as Lugg Meadows and the unimproved fields at New Grove and Pentwyn Farms, it seems that grassland composition will be to some degree out of equilibrium with its present management. Under traditional farming, recovery from ploughing or changes in management would have been fast, because soils were scarcely changed by cultivation, species survived on margins and in corners, and there was always a good deal of semi-natural grassland nearby from which species could recolonise. Today, recovery is more difficult. Outside the gorge and parts of the Woolhope Dome, the soil of any land that is allowed to revert to native grassland may have been permanently changed by deep ploughing, drainage and heavily fertiliser applications, and there will be few, if any, nearby seed sources.

An inability to recover lost ground after changes in management probably spells doom, not just for grassland species in fields, but also for those hanging on in garden lawns. Around Chepstow, for example, several lawns have forms of calcareous and neutral grassland harbouring autumn lady’s-tresses, early-purple orchid and other rarities (Fig. 106). They are safe while the present owner knows

FIG 106. Autumn lady’s-tresses growing in a lawn near Chepstow (see also Fig. 187).

they are there and looks after them, but a change of owner almost certainly brings builders, neglect, weed killers, conversion to a flowerbed, or some combination of these. Once eliminated they will not return, for possible seed sources will be too far away.

MARSHES

Marshes are the wet form of grassland on fertile soil. The roots of the rushes, sedges and tall herbs that often dominate the grasses remain in contact with water, either because the water table is always high or because the soil is constantly flushed by water moving downslope at or close to the surface. On floodplains, which generally drain freely, they develop beside watercourses, in the long, sinuous depressions left by extinct channels, and around headwaters. On slopes, marshes surround springs, mark out flush zones and line streams. On plateaus, drainage off the flat surface is often so slow that marshes develop extensively around springs and in depressions. Once initiated, marshes expand where peat development or blocked streams impede drainage.

Marshes were once common in the Lower Wye. Most were small patches in ordinary fields, but some were extensive enough to attract individual names. However, being fertile, they were prime targets for drainage and conversion to farmland. Traditionally, small marshes were incorporated into meadows and larger marshes were drained just enough to become summer pastures, but drainage became more efficient in the nineteenth century, the last substantial marshes were ditched and cultivated, and in recent decades even the remnants have become intensive, fertile agricultural land.

Fortunately, the old Floras include enough records to reconstruct the principal marshes. Coughton Marsh occupied a shallow valley cut into the first terrace deposits near Walford. Purchas and Ley (1889) record that such quintessential marsh plants as marsh arrowgrass, marsh cinquefoil, marsh pennywort, tubular water-dropwort, marsh lousewort, common butterwort, lesser water-plantain, broad-leaved cottongrass, hare’s-tail cottongrass, blunt-flowered rush and at least six uncommon sedges all thrived there, though by 1889 the marsh was evidently drying out, for butterwort was ‘probably extinct’ and bogbean was ‘still there in 1882’. No doubt much was lost when the embankment for the Monmouth to Ross railway was driven across it in 1870, but some survived into modern times, only to be finally drained about 1968. Today, this is polytunnel country and the former marsh survives only as a small alder wood, managed as a reserve by the Herefordshire Nature Trust, still supporting marsh-marigold, fen bedstraw, yellow iris, meadowsweet and bog stitchwort.

Just to the north of Coughton Marsh, Ailmarsh was once wet enough to have bogbean and other Coughton Marsh species, as well as blinks and the local parsley water-dropwort. Abbots Meadow, a low, frequently flooded, alluvial meadow near Ross, was notable for the abundance of great burnet, a species that was absent from all surrounding meadows, save for a parallel example on the middle Wye at Letton Lake, part of which survives as the Sturts. Widemarsh, near Hereford, contained greater pond-sedge, early marsh-orchid, blue water-speedwell and bird cherry in a hedge, but the finest marshes surrounded the confluence of the headwaters of the Worm Brook at Allensmore, Coed Moor and the Tram Inn. Here, narrow-leaved water-dropwort, bog pimpernel, marsh arrowgrass, lesser water-plantain, fragrant orchid, common cottongrass, purple moor-grass and many uncommon sedge species could be found. Today, the marshes have been replaced by deep ditches and intensive agriculture (Fig. 41), again leaving remnants as alder coppices with oak standards in the Big Bog, with some marsh marigold, lesser pond-sedge and yellow iris. One wonders whether the Victorian botanists would have minded. After all, the Reverend W. S. Symonds, one of the co-authors of the Flora of Herefordshire, took the view that ‘the stiff clays, as about Allensmore, require draining and much culture.’

One substantial marsh does survive on the Wye floodplain near Preston on Wye. This is the Flits, now a broad valley with a small stream, but once a glacial channel filled with peat and calcareous marls. The open marsh is wet enough to contain branched bur-reed, marsh pennywort, water plantain, marsh arrowgrass, bog pimpernel, marsh-orchids and extensive beds of sedges and yellow iris. Alder woods have bogbean and globeflower, and the fringes have neutral grassland managed as meadows.

The principal prehistoric marsh was the Caldicot Level (Chapter 4), and it is here that the Gwent Wildlife Trust’s Magor Marsh reserve has recovered a semblance of former fens (Fig. 107). Now a mixture of lakes, willow scrub, reedbeds, wet meadows, reens and fringing vegetation, it supports marsh grassland and fens on alkaline peat. Although the present-day fens have developed only in the last 80 years, swamps dominated by reed sweet-grass, greater pond-sedge or common reed have developed, with many other fen species, such as water horsetail, yellow iris, purple-loosestrife, hemlock water-dropwort, reed canary-grass, water dock, skullcap and bulrush.

The limestone plateau is an improbable place for marshes, but there is little doubt that they were once frequent. Field names indicate that there was a marsh near English Bicknor, and there are several marsh names on the Ordnance Survey maps east and south of St Briavels. Many alders survive in

FIG 107. Cattle grazing at Magor Marsh reserve, helping to maintain the balance between marsh grassland and sallow scrub.

hedges, and wet patches in and around St Briavels Common have remnants of a marsh flora, including meadowsweet, marsh-marigold, yellow iris, ragged-robin, great willowherb, common spike-rush and several rushes.

These and other remnants highlight a general point: marshes were an integral part of the landscape until the advent of land drains, the ditching of small streams and regular reseeding of grassland, not just extensive tracts that actually bore the name ‘marsh’, but also small patches and streamside fringes that were incorporated within pastures and meadows (Fig. 108) (Riddlesdell et al., 1948, pp xlix-1). Occasional reminders of this survive, such as the grassland along the upper Mounton Brook, where Trevor Evans found bogbean, marsh arrowgrass, alternate-leaved golden-saxifrage, heath spotted-orchid, southern marsh-orchid, bog pimpernel, marsh lousewort, flea sedge, tawny sedge and yellow-sedge.

Many marshes must have originated as wet woodland, or as scrubby openings in woodland. Remnants survive along streams and on poorly drained rides, but extensive marshes within woods have long since vanished. A hint of the original circumstances can be seen in the significantly named Wetmeadow Wood, near Trellech, where a small mire with open tree cover surrounds a headwater and supports both heath species (heather, wavy hair-grass, tormentil and heath wood-rush) and mire species (meadowsweet, marsh-bedstraw, greater

FIG 108. A marsh with bog pondweed and jointed rush lining the outflow stream from Cleddon Bog in a field otherwise occupied by MG5 grassland treated as meadow.

bird’s-foot-trefoil, soft-rush and purple moor-grass). A famous surviving wooded wetland is the Dropping Well on the Great Doward, where a highly calcareous flow maintains a fen just above a limestone cliff. This is now dominated by pendulous sedge with some common reed, hard rush, purple moor-grass, angelica, hemp-agrimony, water mint, glaucous sedge, marsh horsetail and a good deal of scrub woodland. In the late nineteenth century it also had broad-leaved cottongrass, flat-sedge, great horsetail and water horsetail.

The Dropping Well is not the only marsh associated with tufa deposits. At Wormbridge Common near Treville Forest, bog bean, marsh helleborine, fragrant orchid and meadow thistle grow in a small fen bordered by streams forming deep tufa steps. In a field near Woolhope, a calcareous upwelling has formed a dome of tufa with a small marsh containing bog pimpernel and blunt-flowered rush. And a real oddity: tufaceous seepages on Sedbury Cliff are permanent enough to support common reed and alkaline enough to maintain black bog-rush.

HEATHS AND BOGS

Two centuries ago, the road from Chepstow to Monmouth passed through ‘a succession of heathy commons and rich inclosures’, particularly to the east, where there was ‘an undulating surface of dreary heaths and extensive forests. Among which the Wy [sic] winds’ (Coxe, 1801). Most of this is now farmland.

Ecologists define heathland by the presence of heather and bilberry and other dwarf shrubs, but heaths usually include acid grassland and acid mires (bogs) as well. Heaths developed after forest clearance on light, freely drained, inherently infertile soils, where steady leaching, combined with burning and grazing without fertilisation, has washed nutrients out of the soils, reduced biological activity, and allowed organic matter to accumulate as inert humus and peat, thereby eventually generating podzols (Chapter 2). Depressions and flush zones developed into bogs, with mats of Sphagnum mosses, drifts of cottongrass and tussocks of purple moor-grass. Historically, heaths were strongly associated with common pasturage, and survive today in ancient wood-pastures (notably the Dean), commons and open areas within plantations on former heaths.

Fragments of heath – possibly the original form – can also be seen in the rides of existing and former wood-pastures. For example, Parkhouse Rocks has bilberry, bracken and wavy hair-grass growing under oaks on the Quartz Conglomerate exposure. Patches of heather, heath bedstraw and slender St John’s-wort grow by the rides of Haugh, Chepstow Park and Fedw woods. Haugh Wood even has small Sphagnum bogs, perhaps a small survival of a feature that was naturally frequent on the flat, base-poor land in what became the heathland districts. The Dean retains a thin matrix of acid grassland with bracken and small patches of heather.

Cleddon Bog is the largest surviving example of the heather and bilberry-dominated heaths that covered much of the Trellech plateau (Fig. 109) (Howard & Woodman in Wimpenny, 2000). A remnant of the great Wyeswood Common, the bog and the immediately surrounding heath were spared from nineteenth-century enclosure, presumably because they were not worth converting to farmland. The peat, which is no more than 2m deep, developed around two arms of a small stream that eventually drains down Cleddon Shoots into the Wye. When Richard Bradshaw and Claire Jones took peat cores in October 2006 (Fig. 110), probing revealed a general peat depth of about 1m, except on the west side, where the peat was at least 1.5m deep, forming a great accumulation of

FIG 109. Heather in bloom on Cleddon Bog among tussocks of purple moor-grass, cottongrass and rushes. In the absence of burning and grazing, birch and sallows have tended to spread, but valiant cutting by the local authority has kept the core of the bog open. On the margins, meadows derived from the bog still contain some cottongrass. Marginal plantations are being cut back by the Forestry Commission to extend the heathland and open mire.

FIG 110. Richard Bradshaw and Claire Jones prepare to sample the peat of Cleddon Bog. Their analysis of the pollen in the peat will, for the first time, provide a long-term vegetation history from within the Lower Wye Valley.

un-decomposed Sphagnum on a base of organic lake muds. The bog, it seemed, had spread out from a lake held up in a shallow valley against the margin of Broad Meend. Preliminary results from their pollen analysis suggest that the early, ‘natural’ woods (Chapter 4) were steadily replaced by heather, sedges and Sphagnum at a time when people were creating grassland containing ribwort plantain nearby; and that the bog and its surroundings remained open until recently, when beech, pine and birch increased.