CHAPTER 9

Wild Plants and Fungi: the Wye Valley Flora

EACH SPRING RESIDENTS around the Lower Wye watch a fast-changing sequence of wild colour. First, anemones in the woods generate a mottled carpet of white, then bluebells form great sweeps of blue in woods, hedges, undergrazed fields and bracken brakes, and ramsons (alias wild garlic) covers the moist slopes with brilliant white against bright green. Even the trees contribute, with clouds of bright green on the few surviving wych elms and white clusters marking out geans in the woods, and blackthorn and hawthorn around the fields. Mauve cuckooflowers dominate some verges; meadows fill with oxeye daisies; hedges are lined by banks of white cow parsley and red campion; and even the despised purple balsam colours the river banks.

These are the conspicuous and locally abundant species that make an impact in the landscape. Numerically, however, the wild flora is dominated by a very much larger number of infrequent and often inconspicuous species. Furthermore, vegetation also contains bryophytes and ferns, while fungi pervade the whole terrestrial environment, algae grow on wet surfaces and in water, and lichens grow on trees, rocks and buildings.

This chapter considers this diversity and assesses the degree to which it has changed in the last century or so. Fungi and non-flowering plants are summarised, leaving the emphasis on groups of flowering plants that illustrate particular aspects of the Lower Wye’s wild plants. Orchids are popular and undoubtedly native; lilies and their relatives illustrate ambiguities in the status of wild species; and both whitebeams and brambles illustrate the diversity associated with microspecies.

PLANT DIVERSITY

How many vascular plant species grow around the Lower Wye? In so far as there can be an answer, the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (Preston et al., 2002) provides a comprehensive, modern summary not only of which species grow where, but which are native and which were brought here by people. In order to arrive at a precise figure I have counted all the species recorded between the 40 and 70 northings of the National Grid as far north as 40 easting, i.e. an area that is slightly larger than the district considered in Chapter 3. In order to avoid swamping by microspecies, I have, like the Atlas, treated brambles, dandelions and hawkweeds as single species.

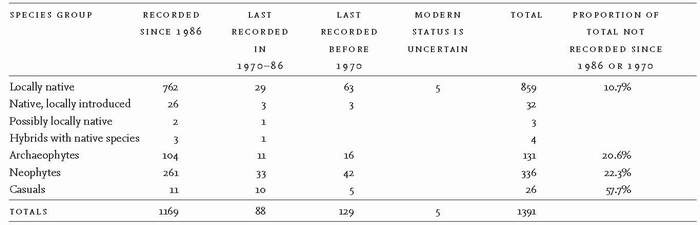

Botanists have recorded 1,391 vascular plant species growing wild around the Lower Wye (Table 11). Some 891 are British natives, but 32 of these were probably introduced to the Lower Wye, leaving 859 local natives that arrived without intervention by people from places where they were native. Natives range from common, widespread and enduring species to rare transients like the lady orchid, which colonised recently, then vanished. The introduced natives are also a mixed bunch. They include Scots pine (prehistorically native, now reintroduced), decorative plants such as summer snowflake, grape-hyacinth and Jacob’s-ladder, and, incredibly, lesser meadow-rue, which seems native enough. Seven more species may count as local natives, including three mint species and Townsend’s cord-grass, which arose as a hybrid between native and introduced species. No doubt there were others, such as great fen-sedge, which prehistorically grew on the Caldicot Level, but became extinct long before the start of botanical recording. On the broadest interpretation therefore, the Lower Wye has supported about 900 native species.

Plants have been added to the native flora ever since the Neolithic farmers introduced crops for cultivation and the Roman gentry made gardens around their Severnside villas. Many eventually became self-supporting in the wild (‘naturalised’) and have long been viewed as natives. Victorian naturalists, however, were well aware of ‘wandering plants’: Dr Bull (TWNFC, 1866, p. 185) doubted that English elm was native; thought the Saxons brought in beech; recorded the first sighting of common field-speedwell (at Ross in 1850); and thought that monks were the source of eyebrights, wallflowers, ivy-leaved toadflax and many others that were then concentrated round former monasteries.

Of course, no records were kept until recently, so botanists have to judge which of the species behaving as natives were actually introduced, using as evidence the behaviour of species in modern habitats, old written records, and

TABLE 11. The number of vascular plant species that grow, or have grown, wild in and around the Lower Wye Valley. (Source: Preston et al., 2002)

fossil plant material in peat or in archaeological remains. On this basis, the Atlas identifies 467 species as naturalised introductions, and a further 26 casual species, which survive in the wild for a few years, but whose populations have to be replenished by further introductions. The naturalised introductions fall into two groups, the archaeophytes that were naturalised before 1500, and the neophytes that became naturalised after 1500 (though some were present before 1500, but had not yet broken free). The authors of the New Atlas have classified as archaeophytes and neophytes many species that we have long regarded as native, and no doubt we will continue to debate whether they were right in every case.

Archaeophytes include many familiar garden plants (e.g. caper spurge, wallflower; Fig. 140), garden weeds (white dead-nettle, field forget-me-not, ivy-leaved speedwell), a few trees (notably sweet chestnut and crack-willow) and a large number of ruderals (‘weeds’) associated with cultivation. Many arrived in prehistoric times. Thus we have acquired former crops (e.g. wild-oat), arable annuals (corncockle, black-grass, red dead-nettle, common poppy) and species now more associated with hedges and field margins (field gromwell, greater celandine, hemlock). Neophytes include everything from commercial timber trees (e.g. lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, sycamore), ornamental trees (holm oak), flowering shrubs (buddleia, shallon, rhododendron), bulbs (snowdrop, glory-of-the-snow, sowbread and various forms of daffodil), garden flowers (snapdragon, fairy foxglove, green alkanet), woodland herbs (lesser periwinkle, pink purslane), shrubs used to shelter game birds (Wilson’s honeysuckle), well-known plants of walls and rocks (red valerian, ivy-leaved toadflax, yellow corydalis; Fig. 142), aquatics and semi-aquatics (water fern, Canadian waterweed, monkey musk), to those bêtes noires of river banks and waste places, Indian balsam (Fig. 125) and Japanese knotweed. The casuals, such as candytuft and garden radish, are mostly rare and temporary escapees from gardens. In short, people have greatly diversified the Lower Wye flora.

The number of species growing in particular woods or fields does not, of course, come close to the 1,169 species that currently grow wild in the Lower Wye, for many are rare or confined to particular habitats. Individual small woods contain perhaps 40-50 species, whereas large woods have perhaps 250-300. Each meadow looks diverse, but it may have no more than 30-40 true grassland species, though a few others stray a few metres in from the margins. On a slightly larger scale, our six hectares of meadows, hedges, walls, garden, woodland, scrub, pond and a headwater stream on acid soils in St Briavels has 181 wild species, of which no more than 50-60 could survive if our holding reverted completely to woodland. Here again we see that, by disturbing ground in the garden and maintaining pastures and meadows, we and our predecessors have greatly diversified the flora.

Diversity can also be assessed in relation to geology and landform, and here there is no doubt that the richest parts of the Lower Wye are the limestone districts along the gorge. Whether we are looking at total species lists or localities of rare species, the Doward, Symonds Yat, Wyndcliff, Haugh Wood and associated land repeatedly yield the most. Within these, perhaps the richest patches will be the short turf on the rock towers, which support perhaps 20-30 species in a single square metre. The marshes may also have been rich, but the largest have been drained and the survivors have been impoverished.

RARE SPECIES AND THE GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT

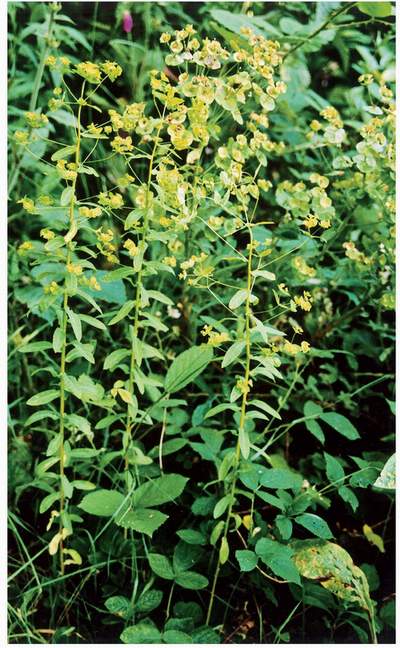

Plant diversity is inflated by a large number of rare and local species. A few are nationally rare, notably the microspecies of whitebeam, bramble and hawkweed, such as the bramble Rubus trelleckensis and the hawkweed Hieracium pachyphylloides (see Chapter 8), that are actually endemic to the district and must have evolved near the Wye. Some, like the dwarf sedge on the Seven Sisters, require a habitat that is naturally rare. More, like green-winged orchid, have had rarity thrust upon them by habitat destruction. Others were confined to one or two locations when botanists first started to notice them, yet they grew in apparently ordinary habitats, and the reasons for their rarity remain obscure. Examples, all of which have now gone, include Plymouth pear (recorded from hedges by the Wye at Dixton and Wyastone), green hound’s-tongue (woods on limestone at English Bicknor, Coldwell Rocks and Dennel Hill), purple gromwell (edge of a wood at Carrow Hill) and Deptford pink (pastures near Monmouth and Penyard Park). A few just appear rare: for example, the upright spurge (alias Tintern spurge) (Fig. 154) only appears sporadically, but must be present as vast numbers of dormant seeds in the soils of woods on limestone in the southern parts of the district.

One recurring characteristic of locally rare species is that, in the Lower Wye, they are growing on or near the edge of their national range. They may or may not be common in other parts of Britain, but in the Lower Wye they are presumably struggling against the limits of their tolerance of some factor that affects their growth, reproduction or dispersal, and this has limited them to ideal sites. The dwarf sedge, for example, is right at the northern limit of its range in Britain, so it is hardly surprising that it grows on one of the warmest and driest sites available.

FIG 154. The upright or Tintern spurge, a species of limestone in the southern part of the gorge and southeast Monmouthshire. It seems rare, but may be abundant as dormant seed. It is regularly awakened on forest roadsides, and has been known to come up in millions, for example, after clear felling for conifers in Black Morgans Wood, or after clearance of dead elms in Coed Wen near Penhow.

Many species occur principally in the uplands of northern and western Britain, where they are associated not just with high altitudes and the pastoral land uses in the hills, but also with peaty or coarse, base-poor soils or rocky coastlines. Those within the Lower Wye are commonly associated with heaths (e.g. heather, cross-leaved heath, marsh St John’s-wort), acid grassland (green-ribbed sedge, sheep’s-bit, mat-grass) and bogs (round-leaved sundew, bog asphodel, bog pondweed, marsh violet). The west and north of Britain also enjoys an oceanic climate – humid and relatively frost-free – and this is what counts for a select group of ‘Atlantic’ species formerly found in the Wye Valley, notably Killarney fern, Tunbridge filmy-fern and hay-scented buckler-fern, which were confined to sheltered, shaded sites, and royal fern, which liked streamsides. Other signs of oceanicity are apparent on the Trellech plateau and the high ground by the gorge, where ferns and bryophytes grow copiously in woods and on walls, and bilberry is abundant on the heaths.

Other species reach, or reached, their southern limit in the Lower Wye. A few inhabit rough grassland and scrub (mountain everlasting, limestone bedstraw, soft downy-rose), but most are woodland herbs and grasses. The populations of intermediate (or upland) enchanter’s-nightshade, bird cherry and wood stitchwort were always weak, but stone bramble was well distributed, and oak fern still is. Giant bellflower, mountain melick and wood fescue are scattered through the woods in the gorge, where they run counter to expectations by maintaining substantial populations to the very limits of their ranges.

The species of the uplands are complemented by the many species whose centre of distribution is in the lowlands, and which are thus most frequent to the east of the Wye. Inevitably, given the pattern of land use in Britain, arable weeds are well represented, but so too are species of more natural habitats. Many species of pools and slow-flowing rivers, such as rigid hornwort, flowering-rush, lesser bulrush and arrowhead, reach their western limits near the Wye. Likewise, the characteristic meadow umbellifers, greater burnet-saxifrage and pepper-saxifrage hardly go further west, and large bitter-cress, a species of wet woods, reaches the southwestern limits of its predominantly northern and eastern range. Deadly nightshade, white helleborine, fly orchid and wood barley, all species of limestone woods, reach the very edge of their European range in the Lower Wye. Even common calcicoles, such as traveller’s-joy, are much rarer to the west, and several others simply thin out westwards. Thus, horseshoe vetch and round-leaved crane’s-bill are fairly frequent to the east of the Wye, but to the west they are almost confined to the coast.

You will find species on the edge of their range wherever you look in Britain, but the boundary between upland and lowland Britain is a particularly clear biogeographical borderland. The Lower Wye not only lies across this transition zone, but its borderland character is reinforced by several species that reach their northern and southern limits in the region. Situated close to the southwestern peninsula and the warm climate of south Wales and Pembrokeshire, several species that are largely confined to southwest Britain reach their limit in the Lower Wye, notably several limestone associates (e.g. southern polypody, ivy broomrape, madder), wall and rock plants (navelwort, rock stonecrop), heath species (bog pimpernel, ivy-leaved bellflower) and others, such as tutsan, leafy rush, chives and eyebright (Euphrasia anglica). Sometimes northern and southern species intermingle: the Wye gorge must be the only place where one can see giant bellflower and mountain melick growing within a few metres of madder.

Not all species can be assigned to a clear geographical pattern. Some are simply patchy in their national distribution, with no clear indication of why. The Lower Wye lies within a ‘patch’ for some of these species, and this brings in the colourful meadow saffron, daffodil, bloody crane’s-bill and monk’s-hood (Fig. 84), and the less colourful small teasel, southern wood-rush, fingered sedge (Fig. 155), pale St John’s-wort, common wintergreen, lesser hairy-brome and narrow-lipped helleborine. Stinking hellebore is widespread as an escape from gardens, but the

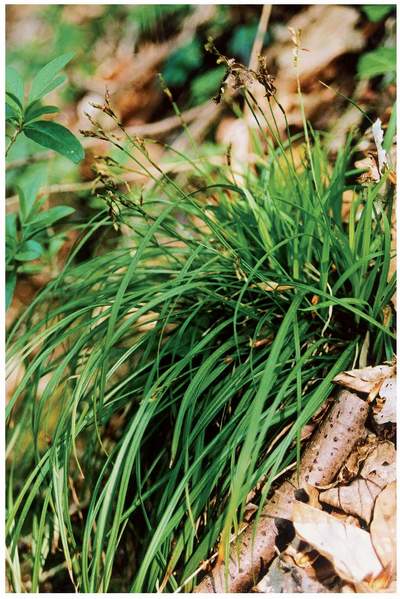

FIG 155. Fingered sedge in the ancient woods below Pen Moel cliffs. This is a restricted species of dry limestone woods.

Lower Wye is central to its native distribution. The most conspicuous is the mistletoe, a widespread species that seems far more abundant in the southern Welsh borderland than elsewhere.

ORCHIDS

Around St Briavels Common, every landowner with the least interest in the environment seems to know whether they have orchids in their fields. Many years ago, I was told in whispers that the most charismatic of British orchids, the lady’s-slipper, had been found in a Wye Valley wood, but I have never found a local botanist who knew this, and I now dismiss it as a botanical ‘big cat’.

Rumours aside, this glamorous family is represented by 27 species in the Lower Wye, and their ecological range and modern fate typifies the native flora. The commonest, by a distance, is the common spotted-orchid, a species of meadows, pastures and woods. In woods it is quite capable of growing under a light canopy, but it is most abundant along open rides and forest roads. In grassland it can be abundant, especially on base-rich soils, though rarely as striking as the magenta carpets it forms in the New Grove meadows against a backdrop of the distant Black Mountains (Fig. 100). Our meadows on acid soils in the Hudnalls contain a few each June, and it occasionally appears in flower borders under maturing shrubs.

Other widespread and locally common species are more closely bound to the limestone woods than the spotted-orchid. Bird’s-nest orchid and greater butterfly-orchid are frequently in the upper gorge woods, the Tidenham-Chepstow limestone area, some scowles, the Woolhope Dome and elsewhere. Broad-leaved helleborines are widespread, but not frequent, in shade and grassy wood margins. Early-purple orchids and twayblades are both now seen principally in woods, usually in moderate shade, and both are common in the woods along the upper gorge, but old Floras describe them as species of meadows and pastures, as well as woods. Ploughing and grassland improvement have turned both into woodland species, though they can still occasionally be found in grassland (Fig. 152), and twayblades are still frequent in New Grove meadow and some of the meadows in the Hudnalls. Being green-flowered, twayblades are inconspicuous, but anyone who finds one can share Charles Darwin’s fascination with orchid pollination by using a pencil to mimic the action of an insect. Simply insert the point into the flower and withdraw: two pollinia will be attached, and will bend forward slowly so that they fertilise the next flower into which the pencil is inserted.

The remaining woodland species are now uncommon, rare or locally extinct. The white helleborine, which is at the western limit of its range, has been seen on the Doward, around Symonds Yat and at Scowles near Coleford. Its close relative, the narrow-leaved helleborine, was scattered through the lower gorge, Lydney scowles and Haugh Wood, and still thrives near Coppet Hill and Wintour’s Leap. Narrow-lipped helleborine is a very rare inhabitant of the woods between Tintern and Chepstow, while violet helleborine near Symonds Yat is on the extreme western limit of its British range. Fly orchid was also present at several points on the upper gorge and the southern limestone belt, and may still be there. We also have records of a dark-red helleborine, a rare species of northern limestones, in the upper gorge, but Riddelsdell et al. (1948) branded them as misidentifications, and in any case the plant found on the Little Doward was extinguished when the hill became a deer park. The astonishing sighting of the lady orchid is not in doubt. Found many years ago in a quarry on the Whitfield Court estate near Ewyas Harold, and seen only once, this fine orchid is largely confined to Kentish woods, but isolated plants have also been found well to the west in Oxfordshire and the Cotswolds.

The ghost orchid (Fig. 156) is yet another enigma. An elusive and mysterious woodland plant, it was first found in Britain in 1854 by the Sapey Brook, near Tedstone Delamere, close to the boundary with Worcestershire, where it was dug up and never seen again (Summerhayes, 1951). It appeared again in 1876, 1878 and 1882 at Bringewood Chase, near Ludlow, and was later discovered in a completely new area, the beechwoods of the southern Chilterns. In 1910 a single plant was found near Ross by Mr C. C. Mountfort, but after that it vanished and was presumed extinct. However, it eventually appeared again in 1982 in a wood on the Woolhope Dome, and may still be there: it has no leaves and is entirely dependent on fungal associates, so it can persist indefinitely underground.

The orchids of grassland have suffered enormous reductions with the loss of most of their habitat. Green-winged orchid is still abundant where it survives (Figs 98 & 99). Pyramidal and bee orchids are species of limestone grassland, quarries and open spaces in woods: both were once widely scattered and locally common from the Woolhope Dome southwards, but only small populations survive, though both are expanding together on the motorway embankment at Dixton (Fig. 157). Frog orchid was known in base-rich grassland from Ruardean to Tidenham Chase and may still survive. The autumn lady’s-tresses (Fig. 106) was frequent in dry turf and on garden lawns, not just on limestone, but also in the lost Coughton Marsh near Walford: it survives, but in ever fewer places. Small white orchid was recorded from Tidenham Chase, while Burnt orchid

FIG 157. Bee orchid, one of several specimens growing with pyramidal orchid on the Dixton embankment reserve of the Gwent Wildlife Trust.

was known from Lydney Park scowles and a meadow by the Wye at the base of Coppet Hill, but neither has been seen since 1970.

The remaining species inhabited heaths and marshes. One, the heath spotted-orchid, was once fairly common on heaths and heathy pastures, though it is so similar to the common spotted-orchid that its precise distribution before farmland intensification is uncertain. Today it survives on Poors Allotment, the Dean fringes and around Trellech. The lesser butterfly-orchid was once known from several places in the woods, heaths and pastures of the Trellech plateau, southwest Herefordshire and the Tidenham-Sedbury parts of Gloucestershire: it was finally lost from Minnet Slade when conifers replaced broadleaved woodland. Fragrant orchid was found in Cleddon Bog, the Dropping Wells marsh and a scatter of places in southern Herefordshire, including the meadows near the Tram Inn. The southern marsh-orchid was a plant of wet meadows near Hoarwithy, Sollers Hope, Widemarsh and Tintern, and it still grows near Trellech. A darker relative, early marsh-orchid, was known from a marsh near the Severn railway bridge. The marsh helleborine grows near Treville Forest and was once abundant in a marsh by the Pentaloe Brook on the north side of Haugh Wood.

COLOURFUL PLANTS: LILIES, DAFFODILS, IRISES AND THEIR RELATIVES

Orchids are rarely cultivated, so we explain their distribution in natural terms, but the Lower Wye has several species that are both colourful and cultivable, which may thus be escapees from gardens. The families that are particularly affected by this ambiguity are those I used to know as the Liliaceae, Amaryllidaceae and Iridaceae, but they are not alone.

Some species are surely native. Bluebell (Fig. 97) and ramsons (Fig. 83) both form great carpets of colour in late spring, one of the great natural sights of the district. The former is a species of well-drained ground that thrives best on mildly acid soils, but is equally abundant in the limestone and sandstone woods. We classify it as a woodland species, but it is also at home in hedges, on dry stream banks and in ‘pseudo-woodland’ under bracken, and indeed some of the finest displays develop in somewhat neglected fields. In parts of the Lower Wye bluebells are all-pervasive, so much so that it has become a persistent, if beautiful, nuisance in my rockery. Ramsons is more a species of deep, fertile soils, and forms dense stands on permanently moist ground over limestone, or at the foot of flushed slopes. Herb-paris (Fig. 158) is also widespread in limestone woodlands, where, camouflaged among thickets of dog’s mercury, it is instantly recognised by its cross of four leaves (occasionally more) and purple berry. Throughout temperate Europe, wherever ecologists have matched plant distributions against historical maps, herb-paris has been found to be strongly associated with ancient woodland.

Four more natives are confined to woods on dry soils on limestone, mostly the Carboniferous Limestone of the upper gorge and the district west of Tintern and Chepstow. Lily-of-the-valley is common in gardens, but the wild populations seem to be dainty by comparison. Whereas in eastern England it is a species of strongly acid soils in ancient woods and will even thrive on the edges of Sphagnum mires, in the Lower Wye it is restricted to limestone. Angular Solomon’s-seal once grew in the upper gorge and near Tintern. Its relative,

Solomon’s-seal, is also a rare native, found in woods around Symonds Yat and west of Chepstow, but it has also escaped occasionally from gardens. Stinking iris – or, to be kinder, roast-beef plant – is widely scattered from Haugh Wood and Cherry Hill southwards, and at several points on the Welsh limestone areas, but does not seem to have been found in the gorge itself. This is the shiny deep-green iris with inconspicuous, purple-lined flowers, but conspicuous scarlet fruits.

Several species are particularly associated with grassland, but can also grow in woods and hedges. Yellow iris, a characteristic plant of marshland, streamsides, wet meadows and swampy alder woods, was once abundant throughout the district, but has become local and rare during the twentieth century. Much the same fate has overtaken meadow saffron (alias autumn crocus) (Fig. 159). It is hard to believe now, but in 1889 Purchas and Ley described it as a pest that was ‘too abundant to need special localisation’, whose leaves were pulled by farmers to prevent their cattle being poisoned. The mid-twentieth-century Floras of Gloucestershire and Monmouthshire also show that meadow saffron was frequent and locally common: for example, Trevor Evans remembers a field below Lydart Farm that was covered in purple until it was ploughed. Today it is largely confined to a few woods and the heathy grasslands of Merbach Hill, Kentchurch Park and Ewyas Harold Common.

The remaining native species are a mixed bunch. In the nineteenth century the yellow star-of-Bethlehem was abundant on a shady bank near Ross, but it has gone. Wild onion was confined to meadows, roadsides and cornfields along Severnside, the Dowards and around Monmouth. Wild asparagus was known from ‘marshes of Tidnam, near Chipstoll’ in the seventeenth century, and it still grew in Tallards Marsh and a meadow near Lancaut in the nineteenth century. The bog asphodel, with its clumps of yellow stars growing on miniature iris plants, survives in bogs around Trellech and Tidenham.

These undoubted native species have been augmented by a host of introductions, most of which have remained obediently in their gardens. Those that have persisted, if briefly, in semi-natural habitats include the few-flowered and three-cornered garlics, spring crocus, montbretia, Spanish bluebell, Pyrenean lily, garden grape-hyacinth, pheasant’s-eye daffodil, several other cultivated daffodils (two-flowered narcissus ‘sometimes simulating a native plant’ in Herefordshire, according to Purchas and Ley), star-of-Bethlehem, drooping star-of-Bethlehem and butcher’s-broom (which is native to southern England). Where they survive in semi-natural habitats they add briefly to the gaiety of the countryside, but we know where they came from.

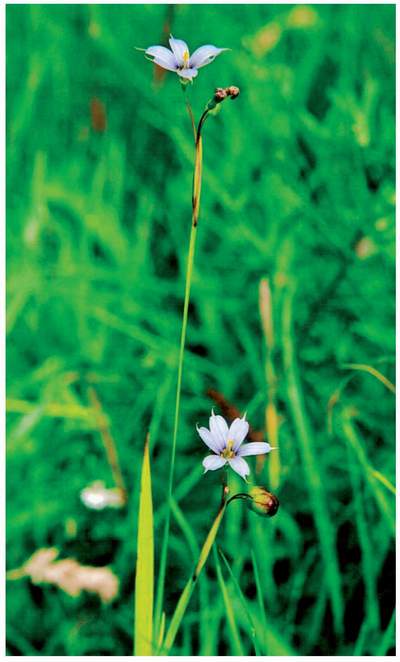

Between the unambiguously native and introduced species are several whose natural pattern may have been altered by transplantation, or whose status as a whole remains uncertain. What are we to make of the blue-eyed grass (Fig. 160) that has recently been found in a wet meadow within Springdale Farm, seemingly natural and a long way from gardens? And what about the widespread pale and dainty daffodils (Fig. 161)? Present in all the woods and meadows around Newent until the 1950s, and seemingly as native as any plant in the district, there were people who thought – without evidence – that they had been planted by medieval monks. Elsewhere, they remain locally common in the Whitebrook valley, woods by the Monnow and on the Woolhope Dome. Best known today as the motorway

FIG 160. Blue-eyed grass at Springdale Farm.

flower, they have become conspicuous on the verges and central reservation of the Ross spur, where they look as if they have spread from the woods. In fact, many were planted by Peter Thomson and others on behalf of the Herefordshire Nature Trust. Evidently, just before the motorway opened, several dustbin-bags were filled with bulbs from a wood on Wormsley Hill that was about to be cleared to farmland, then spread over the M50 verges. No doubt also many people have been tempted to lift a few into gardens, where they can hybridise with cultivars, and from which they can spread to new places in the wild, so at most the native distribution has been slightly modified. Daffodils are still abundant enough in the Newent woods to attract many visitors in April, and they even remain in a few fields, and nobody worries whether they are native or not.

Snowdrops are far more difficult to assess. The New Atlas brands them as neophytes and the old Floras call them denizens, though with some hesitation. Certainly most are escapees from or relicts of gardens. In the Hudnalls woods, for example, clumps of snowdrops still grow vigorously beside the doors of long-abandoned stone squatter ‘houses’ (Fig. 63). The dense concentration of snowdrops along the lower edge of Cadora Woods appears to have spread from a single introduction, and the snowdrops that once grew with another introduced plant, star-of-Bethlehem, in a hillside pasture above Kerne Bridge could hardly have been native. However, the association in the Wye Valley and elsewhere between snowdrops and wet woodland prompts me to believe that some populations could be native. Purchas and Ley (1889) thought the snowdrops in woods and on some bushy stream banks at St Weonards and Garway ‘appeared native’, and those in the alder woods of the lower Mork Brook in St Briavels (Fig. 85) are well scattered through the swamps, not clustered by the stream banks.

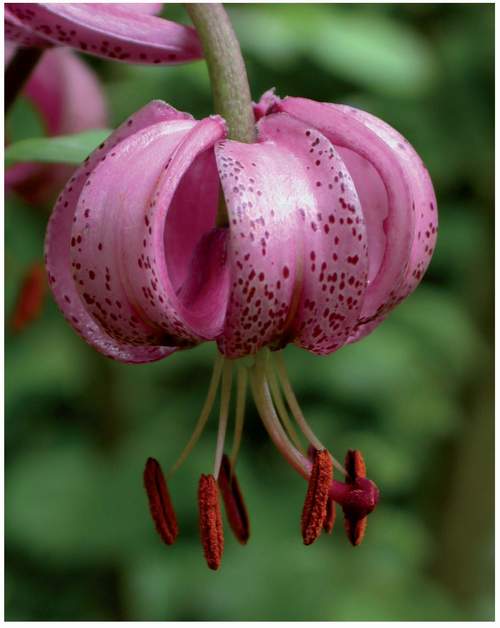

Martagon lily (Fig. 162) and fritillary (Fig. 102) can be treated together, though they are totally different ecologically. The latter grows in the Lugg meadows, well to the west of its former concentrations in the Thames valley, where, since Purchas and Ley (1889) failed to mention it, it may have been introduced. Martagon lily grows in the woods overlooking Tintern and on the plateau behind, where it was quite common until the 1950s, but retreated to three small marginal populations after Oakhill wood was coniferised. Its presence was

FIG 162. Martagon lily in Tidenham Chase.

announced by H. A. Evans in the Journal of Botany in 1884 in terms that were almost identical to the notes I made when I found it in 1970:

In April last, I found a tolerable quantity of Lilium martagon in the old woods on the Gloucestershire bank of the Wye, associated with Paris quadrifolia and Allium ursinum. I afterwards learnt that it was not unknown to the cottagers in the neighbourhood, and I was directed to a clump of the same plant in another part of the woods further from the river. The woods are aboriginal, and the brushwood is only periodically cleared. Moreover, the locality where I first found the plant is deep in the woods, a long way from human habitation; therefore, if it is not native, – and it appears to be quite as native as the Paris, – I should be glad if any one could tell me how it got there.

Shoolbred (1920) also thought it was native: ‘It grows very luxuriantly, far more so than in the Surrey locality, or as usually seen in gardens, appearing quite as much at home as any other native species associated with it.’ However, Harvey (1996) has argued that both martagon lily and fritillary are early introductions, and this verdict has been adopted by the New Atlas, even though the case for fritillary being a native to Britain, if not the Lugg, has been supported by Oswald (1992). As for the lily, while most British populations are certainly escapees, some southern populations, like the Tidenham plants, are long-established occupants of ancient woods far from gardens, just what one would expect of a native population.

WHITEBEAMS, SERVICE-TREES AND ROWAN

The small trees of the genus Sorbus are one of the nationally important features of the Wye gorge. The commonest is the rowan (S. aucuparia), familiar for its ash-like pinnate leaves and dense clusters of red berries. Nationally, rowan is found most frequently in the shade of oceanic oakwoods, the heathy beech-oak woods of southern England, and the Highland birch and pine woods, but in fact it is virtually ubiquitous in woods on strongly acid soils. In the Lower Wye it is widespread, but most abundant in the sandstone woods of the middle gorge. In St Briavels it gives its name to Quicken Tree Wood.

Next is the wild service-tree or chequer tree (S. torminalis; Fig. 163) (whence numerous Chequers Inns) with its maple-like leaves that turn bright orange in autumn. This, too, is usually found in the understorey of dry, mostly acid woods and on open limestone rocks, but, being a species that spreads largely by suckers,

it is confined to ancient woods. Indeed, with small-leaved lime it has long possessed a mildly charismatic reputation as one of the best ancient woodland indicators. In the Lower Wye it is widespread but most frequent in the woods around the upper gorge, where it is concentrated on the dry sites above the cliffs. It is quite capable of growing into large trees, but in Herefordshire coppices it was always treated as underwood.

Then we come to the whitebeams, and this is where it gets complicated. As a group, they are readily recognisable by the grey-white downy undersides of their leaves, but the many species are distinguished only by fine differences in leaf shape and fruit colour. By far the commonest and most widespread is the common whitebeam, with rounded, pale leaves. This, like all the other species, is largely confined to dry, alkaline soils on the limestone: indeed, its most characteristic location is on and near the cliffs, where its pale foliage contrasts dramatically with the yew and beech. In the New Forest and southeast England it is also found on strongly acid heaths, so we should not be too surprised when it is also found occasionally on the Wye Valley sandstones.

The common whitebeam is Sorbus aria. Like rowan and wild service, it is an ordinary, sexually reproducing, diploid species, but the other whitebeams are mostly tetraploids and triploids reproducing apomictically, i.e. without fertilisation, thereby perpetuating mutations. Six such ‘species’ have been recorded from the Lower Wye, all confined to limestone cliffs and their immediate vicinity. Most are concentrated in the upper gorge from Coldwell Rocks past Symonds Yat to the Seven Sisters, and to the Wyndcliff, Pen Moel Rocks and Ban-y-Gor Rocks in the lower gorge. Sorbus anglica, S. eminens, S. porrigentiformis, S. rupicola and hybrids between service and common whitebeam (known as S. vagensis, i.e. it was named after the Wye) and between rowan and common whitebeam (known as S. thuringiaca) are the entities involved. Of these, only S. rupicola has a widespread but sparse distribution on limestone elsewhere in Britain: the others are confined to the Lower Wye and a few other southwestern limestones. In fact, detailed chemical analysis of local populations has shown that the population is still more complex, for the Wye Valley forms of S. eminens differ from those in the Avon Gorge and Mendips, and the S. porrigentiformis of the upper gorge consists of two distinct biochemical forms (Proctor & Groenhof, 1992). Fortunately for the ordinary botanist, intrepid surveys of the 1,200 or so whitebeams on Ban-y-Gor Rocks, Shorncliffand the upper gorge by Libby Houston, Angus Tillotson and Colin Charles have recently shown that most populations are dominated by the diploid S. aria, diversified by a scatter of S. anglica, S. eminens, S. porrigentiformis, S. rupicola, and hybrids with other species, and supplemented by several individuals that did not fit any of the species described so far, and which have recently been recognised as a new species, S. whiteana (Rich & Houston, 2006).

This cluster of microspecies becomes even more remarkable when viewed in context, for several other whitebeams are found in south Wales and southwest England. S. leyana, S. minima and S. leptophylla are confined to two limestone crags in Breconshire; S. wilmottiana and S. bristoliensis are confined to the Avon Gorge, a mirror of the Lower Wye; and S. vexans and S. subcuneata are found only on the coast of Somerset and north Devon. When world lists of endemic trees are compiled, these whitebeams and four others from Devon, Arran and around Morecambe Bay form Britain’s sole offering. Collectively, they present a fine example of a species-cluster undergoing evolution.

Finally, there is a quite different species that eclipses even the whitebeams in some respects. The true service-tree (S. domestica; Fig. 164) was until recently represented in Britain by just one tree in the Wyre Forest, on the boundary

FIG 164. True service-tree on Sedbury Cliff. This individual is vigorous, but it hangs precariously from the cliff and is washed by the highest tides. Other individuals are known along the Severn edge, probably a relict population of an extremely rare native tree.

between Shropshire and Worcestershire, where it is known as the witty pear. (The present tree is actually a cutting taken from the original tree, which died in 1862.) The species is common enough in central France, but the British plant was assumed to have been an import. However, in 1973 some small bushes growing on south-facing Lias limestone cliffs of the Glamorgan coast, which had long been thought to be sterile rowans, were recognised as true service-trees, and this was a location where they could not have been planted (Hampton & Kay, 1995). They appear to be a mixed-age population, which supports the idea that they have reproduced themselves for millennia in their warm but restricted niche. The point for the Wye Valley is that true service has also been found overhanging the top of the tide at the base of Sedbury Cliffs, clinging desperately to a crumbling slope with coppiced sessile oak, pedunculate oak and wild service-trees. This strange tree was long known to Trevor Evans, who never saw it fruit, and it was Mark Kitchen who, having just seen the Glamorgan service-trees, recognised it for what it was, and since then specimens have been found at Chepstow and elsewhere on Severnside. Astonishingly, Nennius, a ninth-century Welsh monk, recorded that apples grew on an ash tree (poma inveniuntur super fraxinum) at the mouth of the Wye (Roper, 2003), a description that well fits the witty pear. Thus, we not only have a representative of the most recently discovered native tree, but we also have a historical record to prove that it has hung on near Chepstow for approaching 1,200 years.

BRAMBLES

Like the whitebeams, brambles illustrate microspecies and active evolution in the Lower Wye. They are ubiquitous in woods, boundaries and the scrub invading fields, where to most modern botanists and ecologists they are just ‘blackberries’, and this is how the great classifier, Carl Linnaeus, saw them in the eighteenth century. Beneath this veneer, however, they are extremely complex, with some 340 species recognised in Britain alone, all subtly different in leaf shape, growth form, the number, size and distribution of spines and acicles, the colour of flowers and the succulence of their fruit. They have breeding mechanisms that throw up a great variety of distinct and permanently fixed forms that live long, spread vegetatively and set copious seed that is spread far and wide by birds. Each bramble species is spreading out like ripples on a pond from its point of origin and other points to which its seed has been transported: some have now achieved ranges that extend widely over temperate Europe, but over half remain endemic to Britain (Allen, 2002). Their classification and nomenclature was in a constant state of flux and uncertainty until the 1930s, but today the main changes occur when new species are recognised. Even so, I have often been confused when trying to reconcile old Wye Valley records with modern taxonomy, and I greeted with a wan smile the news that a form growing around Chepstow was once named Rubus perplexus.

The southern Welsh borderland is particularly rich in brambles, with several very local species, and not just because it was also the focus of interest of two bramble enthusiasts, Augustin Ley and H. J. Riddelsdell, co-authors of the Herefordshire and Gloucestershire Floras respectively. Taken together, the local Floras and Edees & Newton (1988) have applied over 200 names to Lower Wye brambles, but the recent Atlas (Newton & Randall, 2004) records the presence of 122 species. Lists compiled for particular localities give some indication of the diversity. Thus, if one includes the common and widespread types, Shoolbred (1920) lists 36 species from the Trellech area, 42 from Tidenham Chase, 22 from around St Briavels and 19 from around Brockweir and the Hudnalls. Some 19 species were recorded from Chepstow Park Wood alone. These figures reflect a general pattern, namely that variety of habitats and soils leads to variety of brambles, and that the greatest diversity is usually found on and around heathy districts.

Of course, any gardener, fruit picker or countryside manager will already be well aware of bramble diversity. In our own garden one robust plant sent canes some 6m into the crown of some hollies from a rootstock like a knobkerrie, but none of the canes ever rooted at the tip. Nearby, a small, skulking bramble generates weak canes from an ineradicable mass of subterranean stems deeply embedded in a rockery and among tree roots. In the adjacent field hedge another bramble behaves like a missile, producing strong canes that arch over one’s head, then divide into multiple re-entry shoots as they approach walls, the grass or any other place where they might root. Speeded up by time-lapse photography, these are among the most sinister sights in the natural world. Another on the edge of our wood behaves like a spy, creeping inconspicuously over the boundary and running for up to 8m hidden in the rank, late-season grass before sending down roots from its tips: with such sleeper brambles waiting in the wings, it is hardly surprising that neglected pastures quickly fill with scrub. Yet another bramble is covered in a dense mass of spines, and is indeed known as a ‘hedgehog bramble’. And, looking on the bright side, we all know particular bushes that produce excellent crops ofblackberries.

The classification of brambles is too complex to rehearse here, but two groups are significant and reasonably easy to recognise. One is a small group with sub-erect stems that look like raspberries, but have green undersides to their leaves, and may in fact have originated as hybrids. The commonest of these, R. bertramii, R. scissus and R. plicatus, are found mainly in heathy woods. The other group is the sub-genus Corylifolii, brambles that probably arose as hybrids between brambles and dewberry, and possess leaflets that resemble hazel leaves. Dewberry is common on limestone and clay soils, where it produces thin, low-growing, black canes with a dull bloom, bearing large flowers, but only small fruits. The common Lower Wye brambles in this group on the limestones of the upper gorge and south of Tintern are R. conjungens and R. tuberculatus, whereas two newly described species, R. vagensis and R. ariconiensis, appear to be the commonest towards Hereford.

Watson (1958) gives a list of bramble species that yield good blackberries, and it may be of practical interest to mention those that grow in the Lower Wye. Fortunately, one good species is also the commonest of all, especially in hedges and thickets on limestone and clay soils. This is R. ulmifolius, a species with robust prickles and small leaflets that become convex as they age and have strong white felting beneath. One of the best is R. pyramidalis, a species of woods, not hedges, that was common in Chase Wood, King Arthur’s Cave on the Doward, and around Lancaut, Tidenham Chase and the Forest of Dean. This is a late-flowering species with numerous straight prickles and a pyramidal inflorescence. The third common good blackberry species is R. vestitus, a species of woods and thickets, which has a purple, woolly stem, round terminal leaflets and hairs on the underside of the leaf veins. A further three species are frequent in and around the lower valley. R. platyacanthus is frequent in the Dean and both sides of the valley: this has tall, simple canes that rarely root, and large, usually white, flowers. R. scaber is abundant around Tidenham Chase, Madgets, Hewelsfield and St Briavels: it forms small bushes on heaths, but large, arching stems in woods, both with greyish leaves with blue-green undersides. In Herefordshire, several species with succulent fruits and large leaflets are found in woodland glades, which were – and may still be – common on Welsh Newton Common, Howle Hill, Penyard Park and the Broadmoor Common end of Haugh Wood.

Some 23 endemic species of very restricted distribution are centred on the Lower Wye (Newton & Randall, 2004) and must actually have originated within the area. Many were first described from the favoured locations of Victorian botanists, such as Haugh Wood, Howie Hill, Sellack, Garway and Treville Wood, and form part of the ‘Archenfield complex’, a well-marked concentration of bramble diversity. One is Rubus trelleckensis, or Trellech bramble (Randall & Rich, 2000). This species was first collected in 1885 by Ley, but, in the century or so since it was recognised, taxonomists have struggled to fit it into the unstable Rubus classifications and relate it to similar Rubi in Britain and western Europe. In fact, Trellech bramble has borne no less than six Latin names, and has only very recently achieved its current label, so it appears under disguise in the local Floras. A survey in 1998 found it in five sites, all on the heathy ground of the former Wyeswood Common, but its main centre remains in the conifer plantations and remnant heathland of Beacon Hill. Despite searches, there is no sign that it occurs south of Bargain Wood, nor across the river on the Hudnalls. Beacon Hill is also one of just three local stations for R. halsteadensis, but this species is now also known to be widespread in southeast Yorkshire. Three other species are known from single locations, R. dobuniensis at Mitcheldean Meend, R. regillus near Hereford, and R. herefordensis at Caplar Wood. R. rossensis (‘the bramble of Ross’) was first described from a hillside above Redbrook and is common south of Ross, but it is now known from Ireland and elsewhere in southern England.

FERNS

Ferns were diverse and abundant enough to attract one of the great Victorian collectors to live near the Lower Wye Valley (Chapter 1) and brought droves of collectors and botanists into the district to find, and in some cases eradicate, rare species and unusual forms of common species. As William Hill said in a late-nineteenth-century Wye Tour guide (published by the Ross Gazette),

the number of fern growers is rapidly increasing, and the haunts of ferns are being rapidly searched. Nowhere in the county is there a better locality for ferns than Symond’s Yat. The male fern, the lady fern, and the hart’s tongue are as abundant as blackberries in autumn; the blechnum, the wild maidenhair, and the beech fern are common; the limestone polypody and the oak fern are frequently to be met with; and many of the rarer lime stone forms may be found in the woods.

People responded: for example, Thomas Hutchinson witnessed ‘hundreds of roots [being] grubbed up and taken away by trippers’ (TWNFC, 1900-02, p. 128). Driven by such enthusiasm, botanists of the time coined a profusion of names, most of which have since been forgotten, and left a legacy of nomenclatural confusion that requires modern ecologists to chase old records under unfamiliar labels. Thus, for example, narrow buckler-fern is Dryopteris carthusiana in the modern Floras, but hides under the alias Nephroma spinulosa in the old Floras, while soft shield-fern, now Polystichum setiferum, is to be found under Aspidium angulare. Nevertheless, one can penetrate the fog and discover that not only habitat change, but also botanists, have had a marked impact on the botany we see today.

The gametophyte phase of their reproductive cycle requires moisture, so ferns congregate in shade, mossy crevices, wet gulleys and other humid niches. Once established, however, many can withstand severe drought, and this enables them to thrive on rocks, walls and the limbs of trees, especially in the wetter climate of the Trellech and St Briavels plateaus, where they find plenty of moss within which to get established. Thirty-one species have been found wild, of which only the duckweed-like water fern, an occasional escape from ornamental ponds, is an introduction.

The most significant in practical and landscape terms is bracken, a truly unusual species. Capable of growing on a wide range of soil types, it is particularly abundant on light, well-drained soils in woods, hedges and heaths, while avoiding floodplains, wet depressions, flushes, frost hollows and waterlogged clays. Its vigorous network of underground rhizomes allows it to spread rapidly into pastures, meadows and heaths as soon as they are neglected, and today bracken-infested fields are frequent in the small fields around the gorge. The plant is effectively immortal: the oldest living organism in the Wye Valley is probably a bracken clone.

The oceanic species were always rare, and now three of the four are extinct. Royal fern, which was found in wet, peaty places in Shirenewton, Tidenham and Drybrook, suffered at the hands of collectors. According to Shoolbred, several plants were found to the west of Chepstow in 1898, but they had all been eradicated by 1913. It was once abundant ‘on the Gloucester side’ of Chepstow, and a few plants were still there in the 1890s. These were presumably near Tidenham, where it was still seen in the early twentieth century, but according to a local resident ‘it was soon afterwards all dug up.’ Tunbridge filmy-fern and hay-scented buckler-fern were both known from sandstone woods south of Ross, and the former was also recorded close to the Buckstone. Neither has been seen in recent decades, and once again collecting is implicated: just as Shoolbred was coy about royal ferns near Chepstow, so Purchas and Ley deemed it inadvisable ‘to give more exact indications of the station’ of the filmy-fern. The fourth species, Killarney fern, offers one of the stranger stories in British botany. Once known only from a handful of sites in Cornwall, west Wales and further north, it has recently been discovered to be more widespread as the gametophyte. Thus, it has never been seen as a fern in the Wye Valley, but is known from several shady niches as a small plant resembling a thallose liverwort.

Apart from bracken, the ferns of grassland are inconspicuous and rare. Adder’s-tongue was once widespread in native grassland, including damp meadows by the Lugg and by the Wye at Sedbury, and dry pastures on the Doward and Howle Hill. Most of its habitat has been ploughed and it is much reduced, though it survives in several fields. Its survival has been helped by its capacity to bear shade: for example, on St Briavels Common a strong colony survives in young broadleaved plantations on the site of a former meadow. Moonwort was rarer but equally widespread, but it survives in the New Grove meadows near Trellech. Marsh fern has long gone from its mire near Shirenewton.

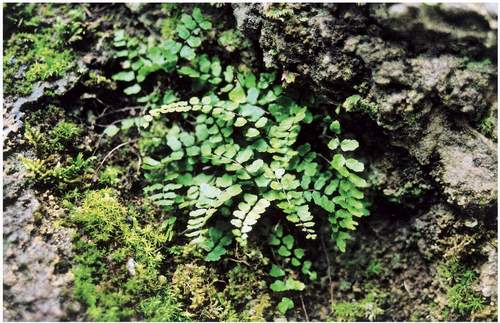

Constant tales of decline and extinction are depressing, so it is refreshing to recognise a group of ferns that have taken advantage of human activity. Black spleenwort, wall-rue, maidenhair spleenwort and rustyback all occur infrequently on limestone rocks on the Doward and elsewhere in the gorge, but are far more common on old walls. On St Briavels Common, the lime-rich walls are instantly distinguishable from the sandstone and conglomerate walls by the profusion of neat spleenworts and rustybacks. Brittle bladder-fern, another infrequent species of shady limestone rocks in the upper and lower gorge, has turned up on the walls of Goodrich, Hereford and elsewhere. Southern polypody was recognised as a separate species only 40 years ago, so early records are somewhat uncertain. It, too, is a natural inhabitant of limestone rocks, but it appears to have grown on Tintern Abbey, Goodrich Castle and a limestone quarry at Newland. Even the distinctive, nationally rare pachyrachis variant of maidenhair spleenwort (Fig. 165) has spread from fastnesses on the Doward, Lady Park Wood and the southern gorge to walls at Monmouth, Chepstow and Caldicot castles. These drought-resistant species of lime-rich niches with a restricted occurrence in natural habitats must have expanded greatly when walls built from limestone or with lime mortar appeared on the scene. However, a few failed to take advantage: the sea spleenwort is known only from one place near Sudbrook, and the lanceolate spleenwort no longer grows near Beachley.

Two other species with more catholic tastes have also spread on walls. Polypody and intermediate polypody grow naturally in woods, where they spread over mossy stones and banks and grow as epiphytes on tree stumps and moss-covered branches. They colonise loose, mossy, conglomerate walls in full sunlight.

The common species, hart’s-tongue, lady-fern, soft and hard shield-ferns, male-fern, scaly male-fern, narrow and broad buckler-ferns and hard-fern, are all associated with woodland (Chapter 5) and other shady places. Scattered among them are four uncommon species that were all once classified as species of Thelypteris. The rarest is the limestone polypody, a species of rocks and woods on limestone and sandstone mainly from Penallt and Whitebrook down to

FIG 165. The pachyrachis form of maidenhair spleenwort, a diminutive plant of moist, shaded limestone rocks that is almost confined to the Lower Wye.

Chepstow, but which was also known from a quarry on the Great Doward. Its ecological opposite is the lemon-scented fern, which was common enough on acid soils in woods, heaths and rough pastures and remains well distributed in the Dean, the sandstone woods south of Monmouth, and the hills south of Ross. Oak fern was common in woods around Chepstow; Shoolbred thought it was in danger of extinction, presumably at the hands of collectors, but scattered colonies survive in sandstone woods on both sides of the gorge, with a few outliers in Penyard Park and nearby. Beech fern is likewise a species of woods on acid soils that survives around the lower gorge and once extended into southern Herefordshire. These are all species of woodland and shady banks that are generally found hiding among a profuse mixture of the common species.

So, did the Victorian fern craze (Byfield, 2006) ruin the Wye Valley’s ferns? Andy Byfield tells me that the collectors gathered many ferns from Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire, particularly varieties of hart’s-tongue and common polypody, but the range of varieties being collected was low in comparison with Devon, and by the 1890s they were propagating and developing new varieties in frames and gardens, including Edward Lowe’s garden at Shirenewton. Some rare species vanished, and possibly also some rare varieties of common species, but the common species must by now have recovered their numbers.

CHANGE IN THE FLORA

The foregoing accounts reveal that, while the Lower Wye still has its diverse, attractive, ‘natural’ landscape of old, its native flora has, sadly, been significantly impoverished. Indeed, as the following three assessments will show, the losses have been almost as great as elsewhere in the British lowlands, and are likely to continue.

The New Atlas provides one way of assessing the changes (Table 11). At least 100 native species have not been seen for at least two decades, and a further 117 introduced, but naturalised, have died out over the same period. As one might expect, native species have been less vulnerable to extinction than introductions. A few will be rediscovered, but most will not. After all, when the only known population of a species is destroyed along with its habitat, for example by ploughing a meadow or draining a wetland, one can be reasonably sure it has gone.

Secondly, we can assess past and potential change in east Monmouthshire (defined as east of grid line 44) from the records collected by Trevor Evans for his Flora of Monmouthshire (2007). By 2003, 60 native plant species (broadly defined) had become extinct and a further 56 survived in just one locality. Some 13 species were lost before 1920, a further 27 went between 1920 and 1970, and another 20 had gone since 1970, an acceleration from about 0.5 species per year before 1970 to 1.0 species per year since 1970, and no conservationist expects the rate to be zero in the future. Many survive elsewhere in the region, and none has become extinct in Britain as a whole, so our local extinctions are not the final word, but part of a larger process of population thinning and fragmentation.

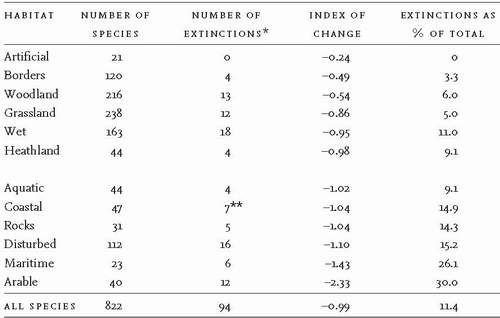

The third assessment is based on Shoolbred’s Flora of Chepstow. Compiled on the basis of observations between 1878 and 1920, this gave a brief assessment of how common or rare each species was within about 15km of the town, so Trevor Evans (who has botanised around Chepstow for just as long) considered whether Shoolbred’s description of the quantity of each species still made sense today and, if not, in which direction it had changed. Allowing for nomenclatural changes and misidentifications (Teesdale violet surely never grew near Chepstow!), and excluding introduced species (as judged by Shoolbred) and the microspecies of bramble, dandelion and hawkweed, some 822 native and ‘colonist’ species were assessed by scoring the degree of change on a nine-point scale of+4 to – 4 (though the great majority fell between +2 and – 2). He also assigned each species to one or more habitat and calculated the average change of each species in each habitat (Table 12). Needless to say, this is not an exact science, but it provides a rough index of change and some insights into the nature of change.

Between 1920 and 2003, up to 94 species became extinct within Shoolbred’s area of search. No habitat was immune: species of arable fields, riverside vegetation, grassland and woodland have all expired. Among the losses, corn buttercup was ‘not very common’ as a ‘colonist in cornfields’ before 1920, and corn marigold was ‘uncommon in corn crops. Stone bramble was ‘common in rocky woods on both sides of the Wye’. Mezereon had already been collected out of the woods near Lancaut and the Barnetts. Bloody crane’s-bill was ‘locally abundant on limestone cliffs and rocky woods and banks. Heath cudweed was ‘not common’ in ‘heaths, hilly pastures; occasionally on banks of streams’, specifically Brockweir Common, Hudnalls, Barnetts Farm, Barbadoes Hill, Trellech Bog, Devauden and by the brook near Pandy Mill. Goat’s-beard was ‘not very common on roadsides, meadows’. Fragrant orchid was locally abundant on ‘rough pastures and commons’. Distant sedge was ‘not uncommon’ in ‘marshy meadows and river banks’ especially along the Wye and Severn. Tasteless water-pepper was ‘locally abundant on river banks’. Grass-leaved orache was ‘not common’ on ‘mud banks, etc, by tidal waters’ around Chepstow. All these species, from a wide variety of habitats, have not been recorded for many years, and only the arable weeds, which could still be present as dormant seed, seem capable of reappearing.

Unsurprisingly, most vanishing species were already rare when they were first discovered in the district. Some 23 extinct species were only ever known from a single locality – royal fern, for instance, last seen before 1920 near Shirenewton, and green figwort, recorded just once on the Wye bank near Bigsweir. A few species grew in several localities, such as corncockle, last seen in 1951 at Wyesham, and heath cudweed, formerly present in at least eight woods, but last seen in 1979 on a path side in Highmeadow Woods. Only seven species described as frequent or locally common in 1920 became extinct.

Detailed analysis would show that many lost species were on or close to their natural limits and that most were represented by small and isolated populations growing on or near the edge of their range. A minority, including most arable weeds, were widespread before 1920, but were first reduced to small, isolated populations by land use change, then each relict population was picked offby local events. Some scattered populations have proved to be resilient (e.g. spreading bellflower; Fig. 166). But for most, ‘those whom man intends to destroy he first makes rare’. Thus, one fears for meadow clary (down to three plants in a field near Rogiet; Fig. 167), marsh St John’s-wort (hanging on in one

TABLE 12. An assessment of the degree of change in the flora of various habitats around Chepstow since 1920. Based on Shoolbred (1920) and a lifetime of observations by Trevor Evans.

* Species not seen for many years where they were formerly observed, despite thorough searches.

** Includes wild asparagus, which was found in Tallard’s Marsh by 1640, but which had probably been eliminated by drainage before 1920.

overgrown bog near the Narth) and many other species that now seem confined to one or two places, for they are very vulnerable to habitat destruction, neglect of management, drainage, eutrophication, plant collecting and ignorance that they are there. By such means we impoverish the countryside.

A few native species have been added since 1920, but few, if any, are real colonists. Four additions are real enough – sea stork’s-bill, service-tree, white campion and rootless duckweed – though they were almost certainly present but overlooked in 1920. Three ferns have been added by recognising new segregates of existing species: the pachyrachis form of maidenhair spleenwort, intermediate polypody and southern polypody. Five whitebeam microspecies and distinctive hybrids have also been added, but these, too, must have been present all along. All the real additions to the flora have been naturalised aliens, including

FIG 166. Spreading bellflower in Cadora Woods. A well-scattered but rare constituent of ancient woods, this species depends on moderate disturbance. In Cadora Woods it survived in an old loading bay and was successfully translocated when the forest road was rebuilt. Moreover, it appeared at three new stations after groups of conifers were removed.

FIG 167. Meadow clary at its westernmost native location near Rogiet. Recently down to two plants, it is the subject of a ‘Back from the Brink’ case study by Plantlife. Agreed changes in management of the field have enabled its population to increase to three plants. (Photo: Trevor Dines)

aggressive species like Japanese knotweed, Indian balsam and New Zealand willowherb.

Even if we ignore extinctions and additions, the balance between gains and losses has been distinctly adverse. Whereas 36 species are thought to have increased, 271 species have decreased. Woodland has been the least affected of the main habitats. Pendulous sedge and thin-spiked wood-sedge have increased substantially in response to deer, and increasing shade has been good for ivy, but many others have lost ground in their alternative habitats: meadow saffron, for example, is now virtually confined to scrub woodland. Traditional arable weeds have declined the most, as they have throughout Britain. The species of rocky, coastal and maritime habitats have fared badly, but the latter are at their limits in the Severn. The species of grassland, heathland, marshes and wet ground have seemingly declined less than the average, a surprising result explained partly by survival in woodland open spaces, and partly as an artefact of qualitative assessments. Thus, for example, sweet vernal-grass was ‘very common throughout’ in 1920, and we still regard it as common because it remains abundant in semi-natural and moderately ‘improved’ grassland. Trevor Evans accordingly assessed its change at – 1, but, with arable and ley grassland replacing most semi-natural grassland, its current population must be no more than 20% of its 1920 population.

The post-1920 fate of the aliens present in 1920 may indicate what will happen in the future to the increasing number of exotic species being introduced from our gardens. Some 46 have not changed much, but 13 appear to be extinct, nine more have declined, and nine have increased, with substantial increases being recorded for gooseberry, winter heliotrope and Oxford ragwort. In addition, several new arrivals have become common or abundant, including Japanese knotweed, Indian balsam, hoary mustard and least duckweed. This is consistent with the Atlas analysis and general experience of life: new arrivals are vulnerable; most are well behaved; a few expand mightily; but only a small minority turn into troublemakers.

BRYOPHYTES

Mosses and liverworts are important components of vegetation, but individual species are difficult to identify. Mosses take the form of cushions, fern-like fronds or straggling mats. Liverworts are either leafy or tongue-like. Some occupy the most inhospitable of habitats: for example, Bryum argenteum grows in the cracks between suburban paving stones and, formerly, on the woodwork of Morris Travellers. Others demand exacting natural conditions, such as a particular soil type, or constant moisture and high humidity. Sadly for the general reader, few have English names, but many of the largely Greek-based scientific names have a beautiful rhythm.

The species that residents see most often are the common mosses of walls and lawns. The wall mosses are species of Barbula, Bryum and Didymodon with Grimmia pulvinata, Schistidium crassipilum and Tortula muralis. Lawns are infiltrated by Scleropodium purum and the euphonious Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus: in April we find ourselves mowing almost pure carpets of the latter, which dry into particularly comfortable places to lie. Perhaps the most widely recognised bryophyte is Funaria hygrometrica, the moss of old bonfire sites.

Bryophytes were included in both Purchas & Ley (1889) and Shoolbred (1920). The Reverend C. H. Binstead, vicar of Fownhope, was in important early-nineteenth-century bryologist. In 1925, Eleanora Armitage, a pioneer of bryology in Herefordshire and the upper Wye gorge (Jones, 1962; Porley & Hodgetts, 2005), led a field meeting of the British Bryological Society (BBS) at Cleddon Bog and Tintern. From the late 1930s onwards, Eustace Jones supplemented his studies at Lady Park Wood with bryophyte surveys around Tintern and the upper gorge, and from 1954 the British Bryological Society visited in most decades. In the 1970s John Port recorded throughout the Lower Wye, concentrating on the woods, and in the 1990s Sam Bosanquet (2003) conducted a detailed survey of Monmouthshire bryophytes. By 2003, some 489 species had been recorded in Monmouthshire, which suggests that the Lower Wye – lacking true upland habitats – contains about 350 species. Nationally, the Lower Wye is significant for its mixture of upland and lowland species, a moderately high diversity within a limited area, and for several species on the edge of their ranges. It also contains most of the population of Seligeria campylopoda and the only southern population of Anomodon longifolius (Fig. 168). A key feature is the abundance and variety of limestone outcrops within ancient woodland.

Bryophytes are abundant and diverse in woods, along streams, on rocks and walls, and on heathland, but they tend to be more limited in grassland. The species described by Shoolbred (1920) as common near Chepstow were particularly associated with rocks, walls, banks, woods and tree trunks, places where shade and moisture were consistently high, and/or competition from ground vegetation was reduced. When John Port surveyed the ancient woods in 1979 he found a total of 171 species, of which 109 species were found in less than 20% of the woods. Those found in almost all woods were Eurhynchium praelongum, Plagiomnium undulatum and Mnium hornum on soil, Isothecium myosuroides and Dicranoweisia cirrata mainly on tree trunks, Lophocolea bidentata on damp

FIG 168. Anomodon longifolius, a nationally rare and decreasing moss of shaded, base-rich rocks, which is found on limestone in the Wye gorge. (Photo: Jonathan Sleath)

substrates, and Brachythecium rutabulum and Hypnum cupressiforme on practically everything.

Britain is noted for oceanic species, concentrated in the mild climate and high humidity along the western seaboard, and several of these grow sparingly in the Lower Wye. The key areas for humidity-demanding species are the steep-sided wooded valleys on either side of the main valley, with Cleddon Shoots a particularly important site. Areas in which Quartz Conglomerate boulders are found are particularly suitable, as these blocks provide year-long shade. Notably disjunct humidity-demanders growing in the valley are the liverworts Bazzania trilobata, Jamesoniella autumnalis, Jubula hutchinsae, Jungermannia hyalina, Lejeunea patens, Plagiochila spinulosa and Riccardia palmata and the mosses Cynodontium bruntonii and Rhynchostegium alopecuroides; there is also a historic record of the moss Dicranum scottianum from near Cleddon Bog. The leafy shoots of the liverwort Marchesinia mackaii often turn shaded limestone outcrops black. Commoner humidity-demanders, with slightly wider ranges, include Hookeria lucens, Lejeunea lamacerina, Lophocolea fragrans, the rusty red Nowellia curvifolia and Trichocolea tomentella. Since most of these tend to be slow to recover ground vacated during temporarily adverse conditions, their presence implies that tree cover has always been present in the steep-sided valleys and around rock outcrops.

The same might also be said of more widespread species near the southern edge of their range, such as Microlejeuna ulicina, which occurs from Moccas Park south to Brockweir, and suggests that patches of enduringly suitable habitat have been widely scattered along the valley. Several northern British calcicoles extend to the Lower Wye, including the fuzzy, grey-green liverwort Apometzgeria pubescens, tiny yellow tufts of Cololejeunea calcarea, wiry patches of Platydictya jungermannioides and the bipinately branched Thuidium recognitum. Rhytidium rugosum, a rare outlier of northern limestone grassland, has been found on the Doward outcrops.

Southern species are well represented, but understandably tend to favour warmer and drier niches. Examples include Tortula marginata, which is frequent in England but extremely rare further west in Wales, Scleropodium tourettii, a species of parched grassland, and Cephaloziella turneri, a rare Mediterranean-Atlantic liverwort. Eurhynchium striatulum, Scorpiurium circinatum and Tortella nitida are southwestern species that grow on south-facing limestone outcrops such as those at Little Doward, Wyndcliff and Mounton.

Several locations have long been identified as locally outstanding for bryophyte diversity. Within range of Chepstow, Shoolbred’s (1920) Flora picks out the limestone exposures of Pen Moel Rocks and Wyndcliff, the heaths of Tidenham Chase, Cleddon Bog and the ravine of Cleddon Shoots (alias Llandogo Glen). Cleddon Bog, for example, contained ten species of Sphagnum, the bog-forming mosses, which were rare elsewhere, except in Tidenham Chase and Chepstow Park Wood. However, the rare species were, and still are, concentrated in the ancient woods of the lower and upper gorges, where outcrops of limestone and Quartz Conglomerate combine with variety of aspect to support many rare and local species. Further north, the principal locations are the ancient woods, such as Haugh Wood, and base-rich sites on the Silurian limestone of the Woolhope Dome such as Common Hill, where there are records for Pottiopsis caespitosa and Didymodon acutus.

Bosanquet (2003) gives details for the Monmouthshire portions of the two most important sites. In the lower gorge, the Blackcliff and Wyndcliff are particularly important for their calcicolous bryophytes, and several other outcrops are known to support interesting species, most notably Seligeria campylopoda, represented by three-quarters of the twelve extant British colonies. Limestone provides the habitat for a few scattered patches of Cololejeunea rosettiana and C. calcarea, as well as an abundance of Marchesinia mackaii. Amblystegium confervoides, Campylophyllum calcareum, Eurhynchium striatulum and Leptobarbula berica also occur, usually in rather small quantity, on shaded limestone. An exposed section of the Wyndcliff supports a colony of Schistidium elegantulum ssp. elegantulum, a critical species currently known from very few British sites; the quarry below the cliffs holds Gymnostomum viridulum; the stream running through Cave Wood is lined with Fissidens rivularis and provides sufficiently humid conditions for Lophocoleafragrans and Trichocolea tomentella. Away from the Wye Valley, the limestone west of Chepstow is also of conservation importance: Great Barnets Woods holds Thuidium recognitum, the Mounton area has Anomodon longifolius and Scorpiurium circinatum, while Daggers Hill supports Seligeria campylopoda and Amblystegium confervoides.

In Lady Park Wood the principal interest is the presence of six small patches of Anomodon longifolius on one part of the east-facing limestone cliff. Two thriving colonies of Seligeria campylopoda occupy small pieces of limestone between the reserve and Hadnock Quarry. Numerous scarce species occur in and around the reserve, most of them associated with limestone. Amblystegium confervoides, Campylophyllum calcareum and Eurhynchium striatulum are found on rocks and stones on the woodland floor; Apometzgeria pubescens at its most southerly British site, Cololejeunea rosettiana, Gymnostomum calcareum, Seligeria donniana and S. acutifolia grow together on damp limestone by the Whippington Brook; Platydictya jungermannioides is restricted to the drier main cliff.

The distribution of the common species is controlled by substrate. When Vanessa Williams surveyed the reserve in 1979, she found that Thuidium tamariscinum, Thamnobryum alopecurum, Plagiochila asplenioides, Plagiomnium undulatum, Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus, Fissidens taxifolius, Hypnum cupressiforme and Eurhynchium crassinervium were commonest on the base-rich soils of the lower slopes, and each had a preferred niche on soil, wood or rocks. On the limestone cliff, the common species were Anomodon viticulosus and Porella platyphylla. On the limestone outcrops near the top of the slope, all of these species were present, together with Plagiothecium succulentum, Lophocolea bicuspidata and a variety of species on the limestone, including Bryum capillare, Fissidens adianthoides, F. pusillus, Ctenidium molluscum, Tortella tortuosa and Isothecium alopecuroides. On the strongly acid soils of the middle slopes bryophyte diversity was much reduced, partly because so much of the ground was covered by deep litter, but the assemblage was quite distinct: characteristically it included the calcifuge mosses Mnium hornum, Polytrichumformosum, Dicranella heteromalla and Dicranum scoparium. When Sam Bosanquet re-examined some of Vanessa Williams’ plots in 2004, bryophyte cover had diminished greatly, and some species (e.g. P. formosum) had almost disappeared.

Several other habitats retain interesting bryophytes. Cleddon Bog still supports several Sphagnum species, Cephalozia connivens, Kurzia pauciflora, Odontoschisma sphagni and Mylia anomala. Cleddon Shoots holds humidity-demanders, such as Lophocolea fragrans, Jubula hutchinsae and Trichocolea tomentella, as well as mosses such as the western species Hyocomium armoricum and the minute Brachydontium trichodes. The conglomerate-boulder flora is very interesting: typical species in this habitat on the Trellech plateau are Bazzania trilobata, Barbilophozia attenuata, Campylopus flexuosus, Lepidozia reptans and Leucobryum juniperoideum. The wet, strongly acid carpet of conglomerate boulders in the Tuffs at St Briavels supports a group of upland species, notably Bazzania trilobata, Sphagnum squarrosum, S. denticulatum and S. palustre. In Trellech Hill quarry, Schistostega pennata grows in hollows under two conglomerate boulders, where its protonema reflects a green glow.

A rich assemblage of epiphytes occurs on alders and willows by slow, silty rivers, and is well developed by the Wye and some of its tributaries. Regular components include Orthotrichum sprucei, Syntrichia latifolia and Leskea polycarpa. The vertical banks of eroding sections of the river support Hennediella stanfordensis, Epipterygium tozeri and various Dicranellas. The rare moss Myrinia pulvinata occurs on exposed tree roots in scattered localities upstream from Hereford, although it appears to have declined significantly during the last century, probably due to shading. Tufa deposits form in many places along the Wye where base-rich water seeps out from the banks. Mosses such as Didymodon rigidulus, Palustriella commutata and Eucladium verticillatum play an important part in tufa formation. There are particularly impressive deposits at the Dropping Wells at the Doward, where the uncommon moss Gymnostomum calcareum can be found with Eucladium verticillatum, Palustriella commutata, Cratoneuron filicinum, Jungermannia atrovirens and Conocephalum conicum.

Arable fields left as stubble over the winter are a characteristic feature of the agricultural landscape of south Herefordshire. They form an important habitat for many small bryophytes used to a regular cycle of disturbance. Many survive ploughing by persisting in the soil as spores and specialised subterranean propagules known as tubers. Fields near Ross support a particularly interesting flora including the liverwort Sphaerocarpos texanus and the moss Chenia leptophylla, found here in its fourth British locality in 2003. In Monmouthshire, Sam Bosanquet has found Weissia rostella close to his home at Dingestow.

Old roofs with south-facing Old Red Sandstone tiles are particularly common in Herefordshire, where they have been used extensively in the past on churches and farm buildings. They support a thermophilic community of bryophytes including Grimmia laevigata and the rare G. ovalis, whose nearest natural locality is at Stanner Rocks NNR in Radnorshire, but whose national stronghold is southwest Herefordshire. Both grow on churches at Dixton and St Pierre, and the latter was also recorded on the roof of the Beaufort Arms in Tintern in 1924.