CHAPTER 10

Wild Animals

FOR MANY PEOPLE, animals are wildlife but plants are scenery. Perhaps this is because Britain’s wild fauna tends to be elusive, unattractive, incomprehensible and often pestilential, save for the birds, which are conspicuous, interesting, diverse and recognisable. Even the ubiquitous foxes, badgers and deer seclude themselves enough to excite comment when they are seen during the day, and most people notice mice and voles only when they are brought in by the cat. This unawareness is a pity, for, whether we are talking species or individuals, animals are far more numerous than plants, and, if conservationists valued all species as equals, they should be putting far more effort into fauna than flora. In practice, even naturalists admit to great gaps in their knowledge of the distribution and ecology of most native wild animals.

This chapter attempts to bring out some general features of the Lower Wye fauna by concentrating on mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, butterflies, moths, slugs and snails, namely the groups that most people, including naturalists, know and notice. Fish, otters, water voles, riverine birds and some of the aquatic invertebrates have already been mentioned in Chapter 7, and some aspects of the prehistoric fauna have been summarised in Chapter 4.

BIRDS

Of all the groups of wildlife, birds command by far the greatest public interest; inevitably, far more is known about them than about any other group of wild fauna and flora. The national atlases of breeding (Gibbons et al., 1993) and wintering birds (Lack, 1986), and the annual assessments of population trends made by the British Trust for Ornithology put the Lower Wye in context, and confirm that the birds of the district largely conform to wider patterns and trends. Thus, farmland birds have declined like those elsewhere, so we have far fewer yellowhammers, tree sparrows and skylarks than hitherto, and changes in farming practice appear to be the root cause, for, where land use has not changed, farmland species remain, such as the skylarks singing over Garway Hill. Farmland waders – snipe, redshank, lapwing, curlew – have also declined. For example, curlew have almost gone from the Trellech plateau, ousted by earlier silage cutting that destroys nests. Nationally, there is growing concern about declines in several woodland species, including spotted flycatchers, marsh and willow tits. On the other hand, magpies have increased and blackcaps, which are particularly abundant around the Lower Wye, now overwinter. (The overwintering population seems to consist of eastern European birds that fortuitously migrated westwards and stuck with the habit.)

Nevertheless, a few Lower Wye populations have bucked national trends. Farmland around Clearwell still supports skylarks, tree sparrows and curlew, for example, and house sparrows remain common in villages and around farms. Pairs of bullfinches are still conspicuous and common in the hedges and orchards. Song thrushes are still regular visitors to gardens among the woods around the gorge, and in 2003 occupied 103 territories in the Nagshead reserve. Interestingly, some species have adapted to changing conditions: for example, yellow wagtail was a species of grassland on the Wye floodplain and the main tributaries, but it has recently taken to breeding on the edges of arable fields.

The Lower Wye makes a few distinctive and notable contributions to the national avifauna. The Severn estuary is a focus for migrating birds and important for waders, ducks and geese in winter. The winter population of dunlin is nationally important and whimbrel are frequent in spring. The district supports several upland species either on the edge of their range or as concentrations of population, notably dipper, raven, curlew, redstart, grey wagtail, tree pipit, pied flycatcher, peregrine, common sandpiper, wood warbler and siskin, and black grouse were once present on the heaths near Trellech. Conversely, several lowland species come close to the western edge of their range, such as hobby, yellow wagtail, lesser whitethroat, tree sparrow, collared dove and turtle dove.

With so many trees, woods and plantations, the populations of green woodpeckers, great spotted woodpeckers (Fig. 171), nuthatches and treecreepers are understandably large, but lesser spotted woodpecker is uncommon and declining sharply. They were common in the mid nineteenth century, when one

FIG 171. Great spotted woodpecker at Whitelye Common. (Photo by Ray Armstrong, courtesy of Grice Chapman Publishing)

of Nicholls’ (1858) informants noted that ‘even the two pied species might be obtained here with very little trouble’. Likewise, tawny owls remain common, just as they were 150 years ago. The trees and woods support good populations of woodcock and several small birds, such as goldcrest, wood warbler, blackcap, coal tit, marsh tit and long-tailed tit. Firecrests breed in small numbers in the Dean and Wentwood. Hawfinches remain a local breeding resident in the Dean and in the high trees around Monmouth and Chepstow; nationally they are declining, so the Lower Wye population is important. Nightjars, or ‘fern owls’ (common in the Dean 150 years ago), still visit in summer to nest on heaths and clear-fells in plantations, and the conifer plantations also support strong populations of crossbill and siskin.

The raptors are conspicuously diverse. Buzzards seem particularly common, wheeling and calling over woods and fields, sometimes mobbed by crows. Kestrels declined along with other farmland birds, but sparrowhawks remain common and hobbies (Fig. 172) frequent the Usk valley and the farmland towards the Wye. Goshawk pairs are now established every kilometre down the valley, with perhaps 70 pairs in the Dean and Trellech-Wentwood plateaus. Peregrines

FIG 172. This female hobby was found at Pilstone House by Maggie Biss, injured apparently after hitting a window pane while trying to catch swifts. It was nursed back to health by Helen Scourse (pictured), but the broken wing set out of position. The bird, now named Thomasina, will have to remain in captivity, but permission has been received to use it for breeding. The main threat is now from animal rights activists.

use several cliffs and the quieter parts of large quarries, to the chagrin of pigeon racers. Red kites and honey buzzards are seen occasionally, but there is no evidence that they have bred in the district.

Common birds

Like any other district, the Lower Wye receives its quota of vagrants. To take just one example, an alpine swift was seen over Monmouth in April 1988, several hundred kilometres from its breeding range in southern Europe. Such wanderers, though exciting, are not ‘common or garden’ species. These are the top ten species that Adrian Wood found in a spring and early summer survey of Cadora Woods (wren, robin, blackbird, goldcrest, chaffinch, blue tit, mistle thrush, wood pigeon, coal tit and blackcap), and the common visitors to our bird feeder on St Briavels Common (great tit, blue tit, coal tit, marsh tit, long-tailed tit, greenfinch, nuthatch, great spotted woodpecker, with robin, dunnock, chaffinch and house sparrow lurking below). Jerry Lewis wondered how many individuals he was supporting with his bird feeder near Abergavenny, and, using capture-recapture techniques, found he was host to 71 different blue tits, 23 great tits and 36 greenfinches (Lewis, 1985).

In well-hedged, mixed farmland the number and variety of birds can be huge. Using the methodology of the Common Birds Census, Stephanie Tyler found an average of 270 breeding territories representing 52 species in 51ha of meadows, leys, some woodland and many hedges around Lone Lane in Penallt (Tyler et al., 1987). More than half the territories were occupied by chaffinches, blackbirds, robins, blue tits, wrens and willow warblers. These figures accord well with the results of a Gwent-wide survey, which found that a modal 2 x 2km tetrad of the national grid in the Lower Wye contained 32-59 confirmed and probable breeding species.

A detailed study

The 200-year-old oak plantations at Nagshead have provided the setting for a famous long-term study of pied flycatchers (Fig. 173). These striking migrants were rare in the district before World War II, but when nest boxes were set out in 1942 they were immediately occupied by 15 pairs. Detailed records have been kept ever since, latterly by Frank Lander (1998), showing how the population has changed and how it interacts with nearby populations.

The number of breeding pairs grew rapidly to 100 in 1951, then declined steadily to 29 in 1978. One cause of decline was judged to be the increasing growth of bramble, holly and other shrubs under the oaks, so much of this was cut back in 1974, additional boxes were set out, and, by 1990, the population was

FIG 173. Pied flycatcher in Pwll-Mawr Wood, Penallt. (Photo by Ray Armstrong, courtesy of Grice Chapman Publishing)

back up to 94 pairs. Since all individuals were ringed, it was easy to discover that, like all small birds, most pied flycatchers die young, but that one Nagshead individual lived for nine years, a British record. Ringing also showed that most birds nesting in Nagshead were born and bred there – in the 1990s, the females of some 66% of all pairs had been born on the reserve – but that a few birds moved in from (and presumably out to) nearby colonies in the Dean and Wye Valley. In good years nestlings feast mainly on caterpillars of the green oak roller moth, but in bad years, such as 1996, a cold spring will leave females in a poor breeding condition, heavy rain will wash the caterpillars out of the trees, or predators such as stoats will destroy broods. Inevitably, therefore, numbers fluctuate, but between 1990 and 1995 an average of 25 first-year birds returned to the reserve. Since 1996, sadly, less than six have returned on average, and another decline has set in. The causes are uncertain: changes in their winter range in tropical Africa may be responsible, or climatic warming may be bringing caterpillars to a peak before the birds have hatched.

Changes

The bird fauna is always changing in response to natural changes and human impacts. The Nagshead flycatchers waxed and waned over decades, and shorter runs of counts revealed annual fluctuations in the Penallt farm birds and the herons at Lancaut. Fragmentary records from the distant past hint that some of this is ‘noise’. Remains of teal, water rail, golden plover, herring gull, woodpigeon, jackdaw, raven, starling and avocet were discovered in 2,000-year-old Roman deposits in Caerleon (Gwent Bird Report, 1988, pp 28-9). Mesolithic cranes and gulls left their footprints in the Severn muds (Chapter 4). Today, cranes are unknown, avocets have recently returned to breed at Uskmouth, water rails are rare but regular winter visitors, and golden plovers overwinter only in small numbers, but the other species are still well represented.

Nineteenth-century writers mention contemporary changes. Nicholls (1858, pp 204-6) reported that large hawks and ravens had been much reduced early in the century: ‘[Fifty years ago] you might often observe fifteen or twenty kites and hawks hovering over Church Hill and the Bicknor walks; but now it is not frequently the case that you see one.’ Southall (1884) said that all the larger birds of prey had become rare in southern Herefordshire due to the ‘gamekeeper war’. The peregrine had become very rare; the ‘ignoble’ buzzard was no longer common; the ‘regal kite, formerly plentiful, was only seen at intervals’; honey buzzard had been seen recently at Goodrich, but rough-legged buzzard had been absent in recent years. The two hen harriers seen in the previous 20 years had both been killed. Even the smaller hawks were annually ‘thinned out’: while kestrel and sparrowhawk remained common, hobby and merlin were very rare. A pair of merlins was trapped at Bishopswood in 1883, ‘even to the regret of the gamekeeper himself’.

Changes in other components of the south Herefordshire avifauna were mixed. By the 1880s, song birds had Government protection, so they were increasing. Southall noted that tawny and barn owls were common, though ‘the mistaken zeal of some farmers’ had reduced the latter. Green, great spotted and lesser spotted woodpeckers were abundant and present in most woods. Remarkably, ‘even that rarity, the Great Black Woodpecker, has been, with a good deal of certainty, observed on three occasions.’ Nuthatch and treecreeper were common, and the wryneck, now virtually vanished from Britain as a breeding species, was ‘often heard’. Hawfinch and grasshopper warbler were both ‘regular’. On farmland, woodpigeons were already abundant and were ‘likely to increase as more land goes under cereals’, pheasant and grey partridge were common outside ‘strictly preserved lands’, and red-legged partridges were frequent. Cirl buntings had recently become more common. Lapwing remained abundant, even though Ailmarsh and Coughton Marsh had by then been drained and cultivated: they were ‘very good for the table’. Other waders were rare, due to drainage, the ‘multiplication of sportsmen’ and ‘the general encroachment of civilisation’.

The changes have continued to the present time. Cirl buntings are now confined to south Devon as a breeding species. Wheatears were ‘of course’ common in the Dean, where they were seen near roads and nested in stone walls, but now they are rare as breeders. In the eighteenth century the Hon. John Byng noted that Tintern Abbey was ‘well overgrown by ivy, and properly inhabited by Choughs and Daws’ (Andrews, 1954), and while the jackdaws remain the choughs have gone (always assuming Byng could distinguish between choughs and rooks). Nightingales were infrequent in nineteenth-century Dean, but they ‘abounded in the neighbourhood’. Confirming this, a Chepstow printer, writing in the eighteenth century, said that ‘the cliffs along the Wye, Piercefield Walks and the whole neighbourhood of Chepstow [were] generally admitted to abound more in nightingales than any other part of [Britain]; and their notes are stronger and more harmonious than in other places’ (Kissack, 1978). However, in late-nineteenth-century Herefordshire nightingales were ‘not as common as they once were’ and, confirming the earlier comment, they sang less well than Monmouthshire nightingales, possibly due to ‘the absence of excitement caused by the rivalry of others singing around them’ (an interesting allusion to density-dependence as a factor in bird populations). Since then, their range has contracted and they no longer breed in the district. On the positive side, crossbills ‘sometimes came’ to nineteenth-century Dean, but now they are established as a breeding species.

During the twentieth century, birds were grievously affected by pesticides, but nevertheless many ultimately recovered much of the ground lost to gamekeepers in the nineteenth century. In the 1930s ravens bred only in the extreme north and west of Gwent, but they have since thoroughly recolonised the Lower Wye. Buzzards are again abundant; peregrines famously returned to Symonds Yat in 1982; and Continental races of goshawks have become naturalised (Fig. 174). Interestingly, when the latter returned, their average clutch size was five, a world record, but as the available ground has filled it has declined to three. Even so, Jerry Lewis is convinced that without initial extreme secrecy, which included anonymous publications about goshawks ‘somewhere in Britain’, they would not have become established.

Changing land use has facilitated other changes. Curlew spread from the upland pastures onto the Gwent lowlands during the twentieth century, presumably in response to the increasing proportion of grass on farms, but now they are in retreat as grass is cut earlier. Snipe hang on well enough at Magor

FIG 174. This goshawk was imported from the Czech Republic, where the species is common. The wild population in the Lower Wye arose partly from releases by falconers, and the species is now well established.

Marsh, but drainage has evicted them from farmland. Nightjars colonised the young plantations of Wentwood and Trellech, declined when the trees grew up, but have returned to heath restoration clearances near Tidenham and Trellech. Black grouse once bred on the Trellech heaths, but have long since retreated to a few fastnesses in north Wales and the Highlands, and even the Gockett Inn by the Trellech-Monmouth road, which preserved a faint memory of their former presence, has closed. In this instance the increasingly sharp boundaries between woodland and open land may be to blame, for black grouse require patches of open ground, scrub and woodland in close proximity (Cayford & Hope Jones, 1989). Meanwhile, other changes are local expressions of larger, possibly natural, changes in range, such as the arrival of the collared doves and the retreat of turtle doves and nightingales.

MAMMALS

Wild mammals, unlike birds, are so secretive that we almost forget they are there. Grey squirrels on the bird feeder, rabbits in a field, dead voles on the doorstep, deer glimpsed down a forest ride, mole hills in the lawn and badgers running before the headlights may be all we notice, and the sight of a fox going unhurriedly about its business in broad daylight is an uncommon treat. True, residents who own pastures are well aware that badgers are around (Fig. 175), but to most people it comes as a surprise to find that the Lower Wye has at least 40 species of wild mammal, and that almost as many have become extinct since the last glaciation.

The extinct species fall into three groups. Many species of all sizes were lost as tundra habitats were replaced by woodland after the ice retreated (Chapter 4), and it seems highly unlikely that people were responsible, even for the loss of mammoth, giant deer, elk, woolly rhinoceros, hyena and wild horses. Others, notably brown bear, lynx, wolf and aurochs, lingered into the Mesolithic, when they should have thrived in the enlarged forests, but people evidently hunted them to extinction. Some may have lingered: the last wild population of wild pigs survived in the Forest of Dean and Wye Valley until 1260, and in 1281 Edward I employed Peter Corbet to destroy all the wolves in the borderlands – and this may be what the wolf’s head on a door at Abbey Dore commemorates (Rackham, 1986). Yet others were exterminated in historic times. Beaver, red deer and roe deer were gone by the end of the Middle Ages, but wild cat, red squirrel and water vole survived into modern times. Common seal might also be added to the last group, for they once inhabited the Bristol Channel.

Many present-day species are natives that have been here for millennia. These include up to thirteen species of bat, four carnivores (fox, stoat, weasel and badger), the familiar hedgehog and mole, several rodents (mice, voles and dormouse) and shrews. To these we should add the grey seal, for in July 2003 one was seen to some astonishment drifting up the Wye on the tide past Tintern, and the bottle-nosed dolphin, one of which was stranded at Sedbury in the nineteenth century (Wallace, 1904). Many species have suffered a great deal of persecution: in Herefordshire, for example, badgers were evidently killed because some farmers thought that they killed lambs; hedgehogs were killed to stop them sucking cows’ udders; and a local furrier received 175,000 mole skins between

FIG 175. A road sign by the A466 near the Wyndcliff aptly sums up most residents’ contact with the wild fauna. Badgers are very common in the Lower Wye and can often be seen running ahead of the car as one returns home along the narrow lanes after dark. The main inconvenience they cause is to lawns and pastures, which they tear up in search of grubs. Some of the small fields around the gorge have been completely ‘ploughed’ by badgers, which looks damaging, but diversifies the flora.

1900 and 1905 (Mellor, 1951). A few species were in fact exterminated, but have returned, notably the polecat, otter and probably the pine marten. To these we might just add red and roe deer, for individual red deer occasionally wander into the district, and roe deer are certainly heading our way from southern England, where populations re-established themselves in the wild after World War II.

The remaining species are naturalised introductions. House mice and, less convincingly, harvest mice are regarded as ancient introductions. Brown hare, fallow deer and rabbit were introduced by the Normans: a corbel on Kilpeck church is the earliest depiction of a rabbit in England. Common rats were introduced in the eighteenth century, grey squirrels were added in the late nineteenth century, mink escaped in the twentieth century, and the expanding population of Chinese muntjac deer has just reached the Lower Wye from the east. There is also a strong possibility that medium-large cats have established themselves in the district. Sightings are regularly reported in the local papers; unlucky individuals have reached home bearing scratch-marks; and the Forestry Commission have actually seen two specimens in the Dean with night-surveillance cameras. Johnny Birks of the Vincent Wildlife Trust is convinced they are real, because the character of injuries to sheep is consistent with big cats, and dead sheep are occasionally found high in trees.

Deer

Deer are the species that, through their size and secretiveness, command most attention when they are seen, but they also illustrate the complexities underlying native and non-native status. Red, roe and fallow deer all became extinct during the last glaciation, but only the red and roe returned of their own volition and became widespread in the prehistoric forests (Corbet & Harris, 1991). Reds were hunted from the earliest times but were protected as valuable quarry in the medieval forests. They remained abundant in the Dean until about 1240 (Whitehead, 1964), but they declined rapidly thereafter and were probably extinct by 1350. Roe were also hunted, and were extinct in much of Britain by the eighteenth century. Fallow, which failed to return after the last glaciation, were introduced into the medieval forests, replaced the reds in the Dean during the thirteenth century, and have been here ever since. They were much reduced by poaching in the early nineteenth century, but then recovered in the shelter of young plantations in the new enclosures. Poaching continued, and by 1855 only a few stragglers remained in the Highmeadow Woods, but they recovered again and today they are abundant.

Fallow were the deer of the deer parks, though not exclusively so: not far away at Lingen in north Herefordshire, the Domesday Book records three ‘hays’ for taking roe deer (Darby & Terrett, 1954). Accusations levelled at the Bishop of Hereford’s warden show that considerable populations of red, roe and fallow were present in Penyard Chase and Park in 1354 (Chapter 5). Chases or parks were established at Hadnock and Tidenham by the thirteenth century, and both Kentchurch and Holme Lacy parks existed by the sixteenth century. Two Victorian treatises on English (which included Monmouthshire) deer parks (Shirley, 1867; Whitaker, 1892) record parks that still contained fallow deer at St Pierre and Lydney in the south, Clearwell and Wyastone in the gorge, Kentchurch and Moccas near the Welsh border, and Holme Lacy by the middle Wye. Some 130 fallow were kept in the 113ha of ‘the ancient park of Holm-Lacy’, described by Evelyn Shirley in glowing terms as ‘celebrated for the beauty of its scenery and the magnificence of its timber’. By the end of the century Clearwell had lost its deer, and those at Wyastone were much reduced. Concert-goers at Wyastone now pass the modern replacement for the old deer park on the Little Doward, while Moccas and Kentchurch retain their deer to this day.

Deer were probably always escaping from parks and forests – Whitaker mentioned that escapees were present in the woods around Haye Park in the late nineteenth century – but until the twentieth century they did not survive long in a well-populated and hungry countryside. Wartime gave them their chance, and by the mid-twentieth century fallow deer were well established in the well-wooded districts on both sides of the Lower Wye (Whitehead, 1964), and even occasional red were seen, presumably escapees from the park herd at Eastnor. The main concentration of fallow in the Lower Wye was in the Highmeadow Woods. Meanwhile, roe were spreading from re-established wild populations in southern England and muntjac were spreading out from their original introduction at Woburn. Today, fallow have become extremely numerous, to the point where they threaten not only gardens (Fig. 176) but also the continuing management of native woodland; muntjac have recently arrived; roe are on the doorstep of Monmouth and Hereford; and occasional reds are still seen in the Dean. Deer populations burgeoned during the later twentieth century, not so much because the deer escaped – they had been doing that for centuries – but because we became sentimental. Today, they are regularly culled, but only in the teeth of a constant barrage of complaint and criticism. Some 549 were culled in 2001-03 from the main herds on the Woolhope Dome and in the gorge, and, without such control, fallow would devastate every wood, maraud gardens and endanger traffic. Moreover, the deer themselves would suffer disease and constant road-kills.

FIG 176. Fallow deer circumnavigate our swimming pool. Like many other residents around the well-wooded Wye gorge, we bought a garden and found we were living in a game park.

Recent extinctions and returns

The small carnivores have, like aquatic mammals (Chapter 7) and deer, suffered massive fluctuations in their populations and shown a remarkable capacity for recovery (Langley & Yalden, 1977). Wild cats, polecats and pine martens were originally widespread in Britain, but all three species declined sharply and retreated to tiny remnants in highland fastnesses. Deforestation must have restricted them, but they were finished off by gamekeepers acting for sporting estates. Wild cats became extinct in much of lowland Britain by the end of the Middle Ages, but they were still widely distributed across Wales as late as 1800. They lingered in west-central Wales in 1850, but died out by 1915, leaving relict populations in Highland Scotland. Pine martens remained widespread in 1800, but they disappeared from southern and central England by 1850. By 1915 they were supposedly restricted to rocky ground in west-central Wales and northern England, though there was an uncertain report of one at Kentchurch in 1939 (Mellor, 1951). Happily, pine martens have lately been spreading slowly from west Wales, and there are reliable reports that individuals have been seen again in the Lower Wye (Birks et al., 2002).

The story of the polecat (Fig. 177) is particularly encouraging (Birks &

FIG 177. A polecat, rescued as a weak youngster from Chepstow racecourse and nursed back to health by Peter and Helen Scourse. All attempts to persuade it to return to the wild failed – it kept coming back for its meals – so it lives with its guardians. Its relatives are now spread throughout the Lower Wye, but are rarely seen.

Kitchener, 1999). Once common throughout Britain, polecats were much reduced in the Lower Wye by 1880, and they had gone by 1915, reduced like the pine marten to small populations in west and central Wales, with perhaps a few stragglers in Herefordshire. With the reduction in gamekeeping after World War I, they began to recover: they were increasing in Herefordshire in the 1930s (Mellor, 1951), by about 1960 they were present around Trellech, and by 1969 they were back along the Monnow and the Herefordshire Wye (Walton, 1968, 1970). Polecats have now spread far into the English Midlands, but still avoid the Caldicot Level, probably because they do not like corridors with heavy road traffic. They hybridise with ferrets, but the hybrids are not as competitive as true polecats, so there seems little danger that the wild stock will change substantially. On the border between Herefordshire and Worcestershire, a radio-tracking study of individual polecats showed that there is a polecat to every one or two square kilometres, and that they use woodland edges, field boundaries, farmyards and barns, but avoid open fields. Some with small home ranges (as low as 16ha) live in farmyards and eat rats, but most have larger ranges (up to 50oha) and feed mainly on rabbits. Each individual has several different resting places within its range, principally in rabbit burrows – a most unwelcome lodger from the rabbits’ point of view.

The sad history of the red squirrel has more parallels with the water vole (Chapter 7) than with the small carnivores. Red squirrels were present in the prehistoric Wye gorge (Chapter 4), and until well into the twentieth century they were the common and well-loved squirrel of the Lower Wye. At Littledean Hall there is a fine portrait of an eighteenth-century owner holding his pet red squirrel on a lead. Unfortunately, the introduced grey squirrel spread into Herefordshire in 1931 (Mellor, 1951), had become a pest at Fownhope by 1935, seems to have spread throughout south Herefordshire in the 1940s, and has long since expanded to plague proportions. In Brockweir, Flora Klickmann, who often remarked on the local reds in her diaries, first noticed greys early in 1943, and by the autumn the greys were ‘everywhere’. Reds were still present at Haugh Wood, Woolhope and Harewood in the early 1950s, but they became extinct soon afterwards. Whether there is a simple direct connection between these changes is a matter of some debate, for the reds declined from a peak about 1900 well before the greys arrived, but there seems little doubt that one has out-competed the other. Today, the nearest reds hold on in North Wales, but greys are an abundant and ubiquitous pest. Cute and lively though they are, they strip bark from beech, sycamore and other deciduous trees, leaving dead branches and deformed trunks. In Lady Park Wood (Mountford & Peterken, 1999) they target fast-growing, pole-stage beech, but they also attack crown branches. Look at any crown branch blown from a mature beech and you will see it broken at a squirrel scar.

In recent years some landowners have taken to farming wild pigs for meat, and to no-one’s surprise some have escaped, establishing a small but thriving population in the woods between Ross and Staunton. Leaving aside the hybrid origin of some animals, this represents the return of a native, but it is also perceived as a threat, and not just because pigs terrorise gardeners and hold up traffic on the A4136. Perhaps similar excitements await people living near ostrich farms: an escapee was seen running up the road near Trellech, and there must be a reason behind the name of the Ostrich Inn in Newland.

Bats

The 13 or so bat species include several, such as the pipistrelles, that are common and widespread, and others, such as Beckstein’s and serotine, for which the Wye is marginal, but the species that have attracted most interest are the greater and lesser horseshoe bats (Fig. 178). The gorge and surroundings districts support

FIG 178. Lesser horseshoe bat, one of two related species for which several caves and buildings have been listed as a Special Area for Conservation. This individual, photographed at a roost in March 2005, was waking from hibernation. It is ringed as part of a study by Tessa Knight of Bristol University. (Photo: © Andy Purcell)

FIG 179. Part of the population of lesser horseshoe bats at the same roost in a barn in St Briavels Common. This, the smallest SSSI in England, shelters one of the largest populations of this bat in Europe. (Photo: © Andy Purcell)

significant populations of both species, which, in the case of the greater horseshoe, may be a semi-isolated population with only limited contact with other populations in southwest England and Wales. These bats breed in old houses and outbuildings, hibernate in mines, caves, adits, scowles and tunnels, and feed in unimproved pastures and the open spaces of large woodlands. A survey in 1997 by the Gloucestershire Bat Group found them in caves and mines at Symonds Yat, Lady Park Wood, Wyndcliff, Piercefield, Chepstow Castle, Noxon Park, Clearwell and Bream scowles, and in houses in Clanna, Staunton, Tidenham and St Briavels Common, as well as the belfry at Sedbury Park. The smallest SSSI in England, a small stone barn on St Briavels Common, provided a summer roost for 890 lesser horseshoes in 2006, one of the largest colonies in Europe (Fig. 179). Radio-tagged by Tessa Knight, they are known to feed widely over the Common and neighbouring farms.

Combinations of woodland, lines of tall hedges and unimproved pasture seem to be ideal for many bats, since they provide both feeding areas and routes between roosts and feeding areas that afford some protection from sparrowhawks. Some species, such as barbastelle and Beckstein’s, stay within woodland, and may use crevices in old trees as roosts. In the summer of 2000, Allan Moore carried out a detailed survey in Cadora Woods with a bat detector, and found that the pipistrelles, noctules and other species hunted mainly along rides and the woodland edge, but tended to avoid the coniferous stands. The lesser horseshoes based in Penallt Church feed mainly in the woods of the parish, but range down the scarp woods to Lydart Orles and across country beyond Wonastow to the southern edge of the Hendre (Bontadina et al., 2002).

Dormice and yellow-necked mice

The ‘Great Nut Hunt’ of 1997 showed that the Lower Wye has one of the national concentrations of dormice (Jermyn et al., 2001), a bushy-tailed but secretive rodent of hazel-rich woodlands whose presence is usually detected by finding the characteristically end-gnawed hazel nuts on the ground. In and around the gorge, where woods are large and well linked by hedges, dormice seem to be common, and in the Croes Robert reserve the population was said to be as high as anywhere in Britain.

Using gnawed nuts as an indication of presence, Paul Bright and others (1994) analysed the distribution of this species in Herefordshire woods, thereby demonstrating just how important the pattern and history of habitats can be in the survival of wildlife populations. Dormice were found to be more frequent in ancient woods than in secondary woods, and far more likely to be present in larger woods. In fact, there were indications of a step change at 20 ha: only a small minority of smaller woods were occupied, but 70% of woods greater than 2oha contained dormice, and the species was invariably present in woods of more than 100 ha. Moreover, other things being equal, dormice were more likely to be present when there were other woods nearby, and when a wood is linked by hedges to other woods, i.e. they were more frequent in the least isolated woods. They also preferred ancient woods that had been converted to plantations, a strange finding best explained by noting that these woods contained more unshaded hazel than unmanaged native woods, and tended to be large and clustered. In secondary woods, the most important factor influencing the presence of dormice was proximity to ancient woodland: those woods that were more than 1km from an ancient wood were very unlikely to have been colonised.

Dormice have a low reproductive rate and live at low density, and their numbers fluctuate from year to year. In bad years, the small populations in small woods may die out, but dormice populations in woods over 2oha are evidently large enough to withstand these fluctuations. Small ancient woods may be recolonised from stronger populations in nearby woods, but the Herefordshire study indicates that this is most likely to happen if the woods are connected by the overgrown hedges along which dormice move. Secondary woods not only have less hazel, but some are so isolated from strong populations that dormice rarely reach them and seem unlikely to persist if they do. In a separate study, radio-tagged dormice dispersed 180-665m from the release point, which suggests that only ambitious and adventurous dormice will colonise woods that are further from home. The outcome of all these influences is that Herefordshire’s dormice are distributed in several sub-populations, each associated with a cluster of larger woods.

Yellow-necked mice, like dormice, live in deciduous woods in southern Britain, preferring ancient woods and rarely colonising severely isolated woods (Marsh et al., 2001). The mice were originally recognised as a separate species in Herefordshire in 1885 (Mellor, 1951), though they were known only from a wide scatter of places, such as Goodrich, How Caple, the Woolhope Dome and Kentchester. The southern Welsh borderland remains a centre of distribution.

AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES

Leaving aside the fabled dragon that once harassed Mordiford (Mason, 1987) and the ‘red viper’ that was reported from Garway Hill (TWNFC, 1900), the Lower Wye supports only the widespread species and none of the national rarities. All appear to have been common within the region until the 1960s, when they all started to decline in the face of changing agriculture (Titcombe, 1998). Palmate, smooth and crested newts have all suffered with the loss of farm ponds, but have moved into the proliferating garden ponds and fishing pools. Frogs were once found in huge numbers in the grassy valleys, but now they are rare in the countryside and depend almost entirely on garden ponds, where they still spawn heavily: the last time I saw tadpoles in a stream was in an outflow from a bog on the Narth. Toads have suffered both from the loss of pools and rivulets and from the increase in traffic, which has killed many as they migrate back to their breeding pools. Lizards remain widespread but localised to remaining dry grasslands and heaths, and slow-worms remain widespread, but patchy, at least on the limestone. Adders, too, have declined, but it is the grass snake that Colin Titcombe regarded as the most vulnerable. Once abundant, this species declined in step with the frogs in the 1960s, and by 1974 he firmly believed that he had seen his last snake at Brockwell Farm.

Nevertheless, all the species have been seen recently and appear to be maintaining themselves at lower population densities than formerly (Titcombe, 2006). Nigel Simpson quickly attracted frogs and all three newt species to his new ponds at Tidenham Chase. Both adders and grass snakes remain in small numbers in the dry glades of his former quarry, which he keeps free of trees and scrub, and slow-worms are fairly common. Palmate newts immediately moved into new ponds in our garden on St Briavels Common. In the rough fields above Pilstone House, Maggie Biss regularly saw both adders and grass snakes.

Individuals of several species move surprisingly large distances. Toads are repeatedly found in our garden, but there is nowhere near for them to breed. The fact that newly suitable habitat is colonised implies that these species are always on the move. They are not, however, ubiquitous: for example, we have never once seen a snake in our meadows and pastures. Moreover, changes in their populations may not be wholly due to habitat changes: at Tidenham Chase Nigel Simpson has noted a decline in adders over 30 years, even though the habitats have not changed. He puts this down to the increasing numbers of pheasants, which predate adders. Quite why pheasants have increased is not known.

BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS

Butterflies

Butterflies are well-known and much-loved symbols of summer, but their number and diversity have greatly diminished. Some 49 species have been recorded in the Lower Wye, although several are but distant memories. One of these, the purple emperor, was seen around Symonds Yat until 1976, and was clearly well known locally. Somewhere near the Yat Robert Gibbings (1942) met a small boy, who was wandering in the woods with a butterfly net:

‘Have you seen a dead rabbit anywhere?’ asked the boy.

‘I have not,’ I said, ‘but there was a very fine weasel playing hide-and-seek with me a few yards back. If you follow him you might get one.’

‘I want a rotten one,’ he said.

‘Sorry, I can’t oblige. What do you want it for? Flies for fishing, I suppose, or maggots?’

‘Butterflies,’ he answered. Then in a subdued voice as if confiding a great secret he added: ‘Purple Emperors.’

‘I thought butterflies liked flowers.’

‘Not Emperors. Dad says: “Rotten rabbits for purple emperors.”‘

[He left] searching the undergrowth for some putrescent corpse [while] staring up among the oak branches watching for the fluttering of one of our loveliest and rarest butterflies.

A hundred years ago, the upper gorge seems to have been popular with lepidopterists. Cooke (1913) noted ‘fluttering peacock butterflies, brown speckled fritillaries, and a dozen more’ species on the river-bank herbage. In fact, the ‘Crown employee’ living in the Biblins Lodge was well versed in entomology. He allowed moth-hunters (and anglers) to stay and kept ‘jars in which are caterpillars waiting metamorphosis’ in his sitting room. Many of the 36 local species were represented, and ‘when our friend can net a curious and unusual “freak”, a handsome guerdon from some eager purchaser is seldom far to seek.’

Butterflies are relatively well recorded, and this allows an analysis of their performance in the Lower Wye that tells us much about the impact of habitat change on insects as a whole. Just eighteen species are widespread and sometimes common, whereas four have only ever been recorded as rare casual visitors many years ago. In general, trends in the Lower Wye match those in Britain as a whole (Asher et al., 2001): indeed, three local species became extinct nationally. Butterfly populations vary enormously from one year to the next, so the current condition and trend for each species are reasonably clear (Table 13).

The greatest differences in performance can be related to habitat changes. Consider, first, the wider countryside species, those relatively mobile species with broad habitat requirements that use linear habitats and are widely distributed in farmland. The six species that feed on weeds of cultivation remain common. Their populations have probably decreased, but they have declined only as an

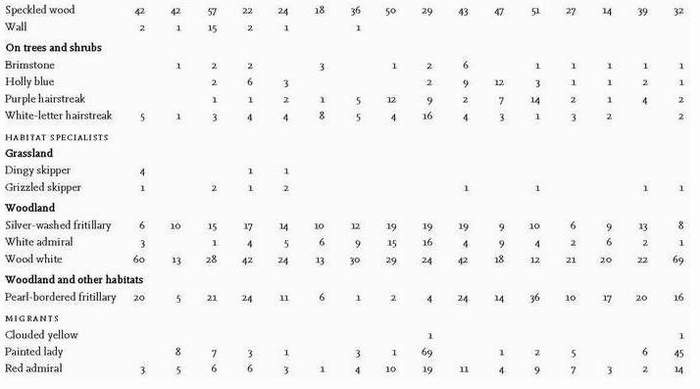

TABLE 13. Butterflies recorded in the Lower Wye Valley.

Following Asher et al. (2001), wider countryside species are those that use habitats that are still common; they also tend to be more mobile. Habitat specialists use patchy, semi-natural habitats, and tend to be less mobile. National trends in population from Asher et al. (2001): (+) expanding; (o) static; (-) thinning; (--) contraction; (---) severe contraction, (x) nationally extinct. Status in Lower Wye Valley determined from Harper & Simpson (2001), Horton (1994) and Meredith (1999). Species in bold are widespread and usually common in the Lower Wye; [] only recorded as rare vagrants in the Lower Wye; *former residents, now extinct in the Lower Wye.

indirect consequence of the increasing area of cultivation and use of fertilisers. This group also includes the familiar migrants, red admiral and painted lady, which breed on the same type of plant, but cannot overwinter. A second group, the species that feed on grasses, grassland herbs, trees and shrubs, are rarely as common as the first, but several are increasing locally and nationally. Marbled white seems to be thriving on the longer grass of neglected pastures and rarely cut road verges and is now quite frequent, but 50 years ago it was very rare (Hallett, 1951). Brown argus, having declined along with its habitat in calcareous grassland, has evidently transferred its tastes successfully to set-aside and urban waste vegetation, but others have declined locally over the last 30 years as their grassland habitats have decreased. In addition, the white-letter hairstreak suffered when disease killed the elms it fed on. The extinction of the black-veined white is a mystery, since it happened in the nineteenth century when its habitats in scrub and orchards were still common. In 1887 it was recorded ‘in the utmost profusion’ at Catbrook, near Tintern.

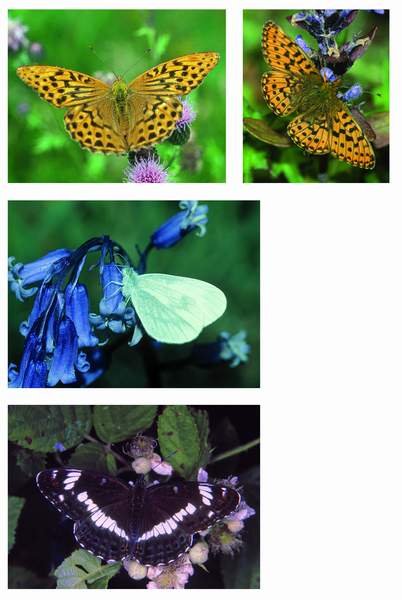

The performance of habitat specialists has been consistently poor or disastrous (Fig. 180). These are the sedentary species that tend to be confined to discrete habitat islands, and which rarely use linear habitats. With only one exception, once-common species have declined to the point where many are

FIG 180. The woodland specialist butterfly species recorded on the Haugh Wood butterfly transect: silver-washed fritillary, pearl-bordered fritillary, wood white and white admiral. (Photos: Andy Nicholls and Butterfly Conservation Picture Library)

now extremely rare, locally and nationally. Thus, the dingy skipper, grizzled skipper and green hairstreak were all common in Herefordshire (Hallett, 1951), but they are now much reduced. Poors Allotment supported dark green, silver-washed, small pearl-bordered and pearl-bordered fritillaries, but not now. In the 1960s the Angiddy valley supported six species of fritillary (Horton, 1994), but by the early 1990s, high brown, dark green, marsh, pearl-bordered and small pearl-bordered fritillaries had gone, and only silver-washed fritillary remained in much reduced numbers. Indeed, in the 1950s Trevor Evans could find 32 species of butterfly in the valley, but now 12 would be a good list. Haugh Wood had lost the Duke of Burgundy and marsh fritillary by 1981, and the silver-studded blue, purple emperor and Duke of Burgundy had gone from the Doward (TWNFC, 1981, p. 332). Today, pearl-bordered fritillaries are still present in Haugh Wood, and wood whites were abundant there in June 2004. Habitat specialists were never widespread, but they could be seen reliably in their chosen places, and their recent history has been of unrelenting decline. The only exception is the white admiral, which has expanded in southern Herefordshire and southeast Monmouthshire, where it thrives on honeysuckle lianas in the increasingly shady broadleaved woods.

Nationally rare species have fared worse. Large copper was ‘less reliably’ recorded from the Somerset Levels and the ‘Wye marshes’ (Asher et al., 2001) before the marshes were fully drained in the nineteenth century. Swallowtail, too, was also once present in the Somerset Levels, and from its former distribution it seems likely that it too was in the ‘Wye marshes’. The large copper became extinct in Britain in the nineteenth century, and the swallowtail hangs on in eastern England.

What lies behind these declines? In a climatically warming world most species should be expanding, but the damaging effects of habitat loss completely outweigh this (Asher et al., 2001). Each species must be subject to its peculiar balance of factors, but collectively the most likely causes are (i) the loss of semi-natural grassland and heath, (ii) reduction in grazing on the remnants, (iii) decline in coppicing and generally less active broadleaved woodland management, (iv) fragmentation of broadleaved woodland by conifer planting, (v) loss of habitat mosaics, notably grass-bracken patchworks, and (vi) loss of hedges combined with mechanical trimming of the remainder. Atmospheric pollution has been implicated in the decline of some Continental butterflies, but there is no direct evidence of this in Britain. In the past, collectors may have hastened the demise of a few, small populations, but there is no evidence of a general impact.

Butterflies are still common, but they are mainly the wider countryside species. Ray Armstrong’s list from Trellech (Wimpenny, 2000) is brimstone, peacock, small tortoiseshell, red admiral, painted lady, comma, meadow brown, marbled white, ringlet, gatekeeper, wall, speckled wood, small copper, small skipper, common blue, holly blue, small white and large white. Pearl-bordered fritillaries were common in the spring meadows, but they have been evicted by changes in farming, and they are now confined to woodland rides. There is still hope for specialists. Martin Anthoney tells me that, in the hot July of 2006, white admirals were frequent again in the Wye Valley; silver-washed fritillaries were seen from the Hendre southwards to the Angiddy; the white-letter hairstreak was seen in the Angiddy and Penallt for the first time in six years, and Essex skippers colonised around Dingestow.

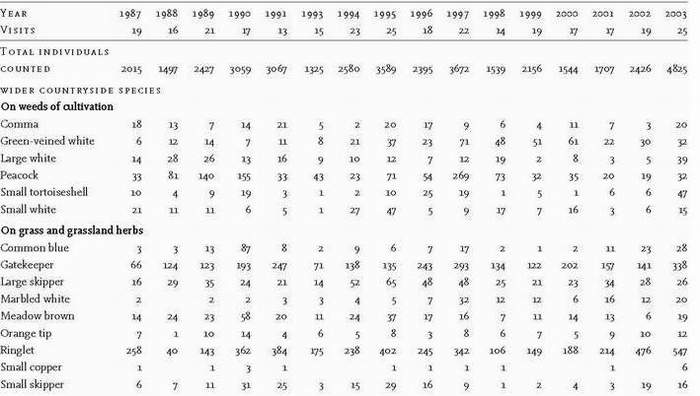

The populations of butterflies – and other insects – fluctuate from year to year, and this phenomenon can be illustrated by records collected since 1987 from the southern part of Haugh Wood. From April to September, Jeff Andrews and other members of Butterfly Conservation have counted all the butterflies seen along a 3.5km standard walk along rides and through broadleaved and coniferous woodland (Table 14). Despite some variation in the intensity of recording, this dedicated effort shows clearly how butterflies in general are abundant in some years, but sparse in others. Gatekeeper, ringlet and speckled wood were consistently the most abundant, and ensured that wider countryside species dominated the counts. Grassland specialists were commoner than woodland specialists, even though the counts came from within woodland, but grassland specialists rarely penetrated far into the wood. Woodland specialists reflected changing management: initially, the light-loving pearl-bordered fritillary and wood white were in decline, whereas the white admiral, which requires shaded honeysuckle lianas, was increasing, but after 1995 the Forestry Commission reversed the trends by opening the rides (Fig. 148) and restoring 4oha of coppice. National trends were reflected in the spread of the marbled white and the decline of the wall; the migrant painted lady was especially variable; and the resident holly blue exhibited a characteristically regular cycle of abundance and decline.

Enthusiasts occasionally release home-bred rarities. Such species rarely establish wild populations, but one, the map butterfly, a Continental species that resembles a white admiral in its later brood and a cross between a fritillary and a painted lady in its early brood, succeeded locally. It was introduced to the upper Wye gorge in 1912, and was well established at Symonds Yat, Ganarew and other places nearby by 1915, but, sadly, it fell victim to the Great War. The collector A. B. Farn collected it to extinction in 1916 on the grounds that no German butterfly should be introduced to Britain (Oates & Warren, 1990).

TABLE 14. A summary of the changing populations of butterflies in Haugh Wood, 1987-2003. The records represent the highest annual counts for each species on the transect through the southern half of the wood, recorded annually by members of Butterfly Conservation.

Moths

The number of moth species in the Lower Wye far exceeds the number of butterflies. Some 555-620 macromoths have been recorded in each of the constituent counties, so the number for the Lower Wye must approach that range, and to these must be added a similar number of micromoths.

An account of changes among the moths of Herefordshire and Worcestershire (Harper & Simpson, 2001) reinforces the analysis of butterfly changes. During the twentieth century seven species took up residence for a few years, then died out. Eight species were newly recognised in the counties, but they had almost certainly been present all along, hidden by their close similarity to related species. The satin beauty, dwarf pug, spruce carpet and the tawny-barred angle colonised the increasing numbers of conifers in gardens and woods. For a time, the dusky sallow spread, like the marbled white, on longer grass. In 1999, the scarlet tiger colonised comfrey on the banks of the Wye.

However, the number of declining species considerably exceeded the number of new arrivals and expanding species. Species associated with calcareous grassland (e.g. pimpinel pug, burnet companion, mother shipton, small purple-barred), wet grassland (e.g. gold spot, blackneck, ruddy carpet) and neutral grassland (e.g. ghost, small blood vein, grey chi) have all declined. Others, notably the forester, cistus forester and five-spot burnet, have been lost to overgrazing, undergrazing or grassland ‘improvement’. The decline of V-moth, spinach and currant clearwing is blamed on the decrease in the area of currants being cultivated. The extinctions of Kentish glory and orange upperwing, and the decline of several species, such as little thorn, silvery arches, star-wort and large red-belted clearwing, are connected with the decline of coppicing and its associated open-space habitats. The decline of the scarce prominent, barred chestnut, northern winter moth and birch mocha has followed the reduction in sallows and other early-succession trees with the lengthening of forest rotations. The loss of elms caused the decline of lesser-spotted pinion, dusky-lemon sallow, clouded magpie and Blomer’s rivulet and the extinction of white-spotted pinion. Climate change seems to be having some effect on the winter moth, whose larvae now hatch earlier, before the trees on whose leaves they feed have broken bud.

This general picture of decline is reinforced by the rigorously quantitative findings from suction traps operated since 1973 at Hereford by Rothamsted Experimental Station (Harrington et al., 2003). Initially, the invertebrate biomass was generally higher than elsewhere, but latterly it decreased. Analysis of the components of the catch showed that the moths had declined, but not the aphids and social wasps. Yet again, habitat loss was blamed, for the species of grassland and other non-woodland habitats declined the most.

FIG 181. Scarce hook-tip, a moth that is found only in and around the southern extremity of the lower gorge, where it feeds on small-leaved lime. (Photo: Paul Waring)

Despite these changes the diversity of moths remains high. In just six nights with a light trap, Roger Gaunt caught 169 moth species in a clearing in our wood on the edge of St Briavels Common, but this is trivial compared with the 712 species he has trapped in 20 years in the well-hedged semi-natural pastures round his house at Coldharbour. Many rare and local species survive, several long-renowned woods remain rich, and Cleddon Bog and Magor Marsh still support species that are rare or unknown elsewhere in Monmouthshire. Perhaps the most exciting area is the southern end of the Wye Valley, where the diversity associated with the conjunction of woodland, grassland, riverside, cliff, coastal and residential habitats is reinforced by the southern aspect of dry limestone slopes. One locality in this district supports four national rarities, including the barred carpet and Fletcher’s pug, and it was here that the scarce hook-tip (Fig. 181), which feeds on small-leaved lime, was rediscovered as a British species in 1961 (Waring, 2004). Another lime-feeder, the micro Dichomeris ustalella, was first recorded at Tintern in 1999. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the district attracts so many lepidopterists that, on one summer night, Martin Anthoney found the Wyndcliff looking like the Blackpool illuminations – 17 light traps were being run simultaneously by 17 moth hunters.

SLUGS AND SNAILS

Terrestrial slugs and snails have, like plants, strong associations between species and habitat, higher diversity on calcareous habitats; several species catholic enough to inhabit woodland, grassland and wetland; a well-defined set of species that are associated with human activity (such as the garden snail); and a contrasting set that are averse to human activity and strongly associated with primary or ancient habitats (Boycott, 1934; Willing, 1993). These properties have been turned to good use by archaeologists and environmental historians, who have used snail shells preserved in soils, tufa and archaeological strata as environmental indicators. Thus Nayling and Caseldine (1997) were able to use the remains of snails, plants and insects to identify the expansion of grassland in the Nedern Valley just to the east of Caldicot Castle during the Bronze Age and a later change to brackish conditions. Earlier, Kennard and Woodward (1924) found 14 of the present-day species in the Pleistocene strata of Merlin’s Cave, on the Great Doward.

Boycott’s early recognition of ‘ancient woodland indicators’ seems to have developed in and around Gloucestershire. In his experience (Boycott, 1930) the ash-black slug and slender slug were species ‘which only occur in old woodlands, never in gardens and cultivated land’. In fact, ‘the diagnosis of an ancient wood depends on a variety of evidence, but there is probably nothing more cogent than the discovery of one or both of these slugs.’ He noted further that

old woods have sometimes been replanted in a misleading way and these slugs may show what has happened; thus Went Wood in Monmouthshire, essentially an oak forest, has been almost entirely turned into a fir plantation, but the presence of slender slug shows the real nature of the place. The misdeeds of the Forestry Commission may give us other similar instances.

The Lower Wye appears to have a range of mollusc assemblages to match the variety of vegetation, but nothing exceptional. Most of the 24 species of slug are habitat generalists with a wide distribution, and several were introduced (Kerney, 1999). The 55 species of terrestrial snails include a higher proportion associated with semi-natural habitats, particularly woodlands and limestone rocks. They include four species associated with ancient woodlands, brown snail, a western species on the edge of its range in the Lower Wye, mountain bulin, a lowland species despite its name, on the very edge of its range, the ash-black slug and the greater pellucid glass snail, a southern species. Wall whorl snail and large chrysalis snail have been recorded in dry, stony places, but not recently, which may be significant, for both have retreated greatly in the thousands of years since the Boreal and Atlantic periods. In two woodland reserves on limestone in the lower gorge, Long (1998) found 29 species in Ban-y-Gor Wood and 42 species in the Lancaut reserve, the larger total of the latter being due to the presence of dry grassland and salt marsh combined with proximity to houses. At Moccas Park, 41 species are listed (Harding & Wall, 2000). All three sites contained the ash-black slug, and the limestone reserves also supported three other ancient woodland indicators, including brown snail.

INVERTEBRATES IN GENERAL

After a decade of collecting by visiting entomologists and the scientists working in the nearby research station, some 2,842 species of invertebrate had been recorded in Monks Wood NNR, Cambridgeshire (Steele & Welch, 1973), and the number will be far greater now. No sites in the Lower Wye have been searched to this degree, but there is every chance that the larger woods are just as rich, and that the district as a whole supports tens of thousands of species in the full range of habitats. Unfortunately, the problems of achieving a comprehensive knowledge of the huge number of Wye Valley invertebrate species are compounded by the general lack of systematic survey. The first records in Herefordshire – of some Hymenoptera – date only from 1832, and even now only the Lepidoptera, Odonata, Diptera and Mollusca appear to be reasonably well known. Herefordshire was a significant place for students of flies, for the collection of Diptera amassed around 1900 by Dr J. H. Wood of Tarrington, a village on the northern edge of the Woolhope Dome, was the most comprehensive in Britain at the time, and included several type specimens (Hallett, 1951). Gloucestershire is probably better recorded, through the activities of the Gloucestershire Naturalists’ Society and more recently the Gloucestershire Invertebrate Group, but Monmouthshire is poorly recorded.

The issues are illustrated by Moccas Park, the only site that has been searched over a long period (Harding & Wall, 2000), and a site to which entomologists tended to swarm after some exceptionally rare species were discovered. The accumulated lists now stand at the formidable totals of over 900 species of Coleoptera, 610 Diptera, 116 spiders and 41 molluscs, and, since many of these species were found only recently, more species must await discovery. The lists of 18 butterflies and 150 moth species are rather more manageable.

The Lower Wye has many of the hallmarks of a good entomological region, a sentiment that was admirably expressed by Eleanor Ormerod (Wallace, 1904). Writing of her early Victorian youth, this pioneer of economic entomology observed:

I was singularly well situated for the collection of ordinary kinds of injurious insects, and for the observation of their workings, as I resided at [Sedbury Park, Chepstow]…The wood- and park-land included old timber trees in some instances dating back to the time of the Edwards, and also plenty of ordinary deciduous woodland and coppice. The fir plantations supplied conifer-loving forest pests; the ordinary insects of crop and garden were of course plentiful; the woodland and field pools added their quota; and the diversity in exposure from salt pasturage by the Severn to the various growths up the face of the cliff to about 140 feet probably had something to do also with the great variety of insect life.

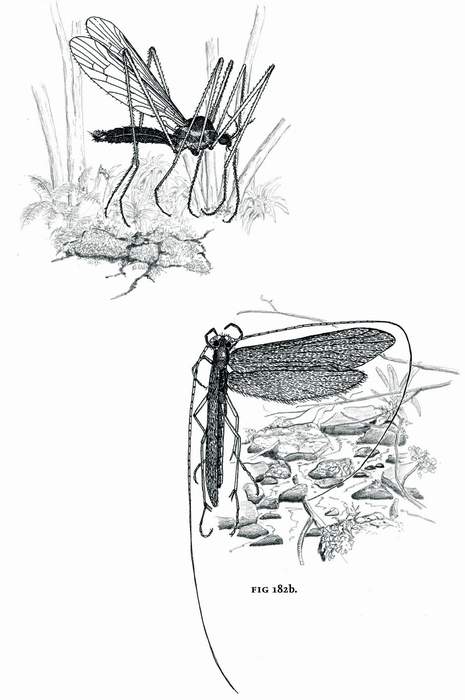

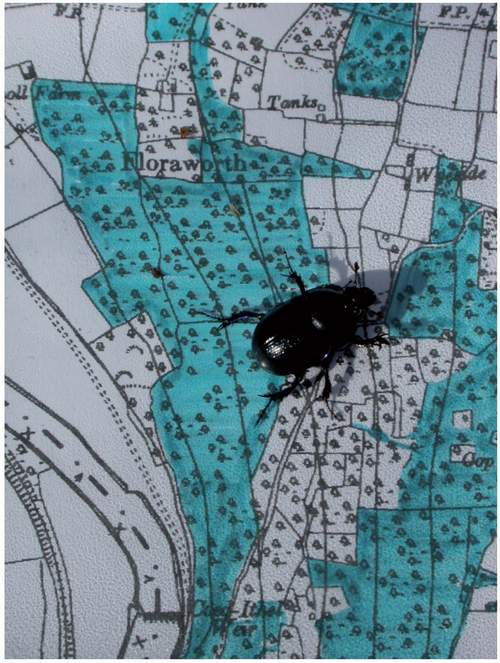

Today, groups of specialists have no difficulty finding local and rare species in any reasonably large and diverse tract of semi-natural habitat. Recent reconnaissance visits by the Gloucestershire Invertebrate Group to Ban-y-Gor and Lancaut Woods, both Trust reserves in the lower gorge, have discovered rare and local species in several groups. These, note, are sites that have been reasonably well known botanically for a century and more. In 1997 the group found the scarce hook-tip (see above), Episinus maculipes and Hyptiotes paradoxus (rare spiders that need old yews), Trachodes hispidus (a nationally scarce relict old-growth weevil), Dirhagus pygmaeus (a rare saproxylic beetle), Malthodes mysticus (a rare soldier beetle), Mompha langiella (a nationally scarce micromoth) and Haplophthalamus anicus (an uncommon woodlouse, found on fallen wood by rivers). A few years earlier, a 1989 reconnaissance of the Lancaut reserve had located Armadillidium depressum, the scarce pill woodlouse, on limestone rubble, and several salt-marsh specialists: Pogonus chalceus (a beetle), Bembidion minimum (a beetle of the clay banks of the river), Broscus cephalotes (another beetle which is usually found on sand dunes), Melieria picta and Ceroxys urticae (both scarce salt-marsh flies) and Ovatella myosotis (a salt-marsh mollusc). The rare pill woodlouse Armadillidium pictum was found near Symonds Yat during a field meeting of the British Entomological & Natural History Society in 1992. In 2004, Peter Kirby found two exceptionally rare species in Prisk Wood (Fig. 182). Inevitably, most of the species encountered are common and recognise no particular habitat type, either because they use more than one habitat, or because they occupy the boundary zones between the habitats we recognise, or simply because they wander from one to another (Fig. 183).

In the 1980s, records of the most important sites for macro-invertebrates

FIG 182. Two rare insects found recently in the Prisk Wood reserve of the Gwent Wildlife Trust: (a) Adicella filicornis, a caddis fly, and (b) Ellipteroides alboscutellatus, a cranefly, both shown in typical habitats. (Drawings by the discoverer, Peter Kirby, reproduced by permission of the Gwent Wildlife Trust)

FIG 183. Ancient woods are important locations for beetles. However, this specimen, photographed in the Hudnalls whilst crawling over a map of ancient woodland, was identified by Colin Welch as probably Geotrupes stercorosus, a relative of the common dor beetle. It was probably attracted by the increasing amounts of deer dung in the wood.

were assembled by the Nature Conservancy Council into Invertebrate Site Registers for each county, and those for Wales have been synthesised for a general audience by Adrian Fowles (1994). Fowles identified several general factors that underlie the occurrence of individual species: (i) invertebrates are very sensitive to microclimate, so shade, aspect and vegetation structure are important; (ii) each species may be particularly associated with a major habitat, but most are associated with particular niches within the habitat; (iii) many invertebrate species require different conditions at different stages in their life cycle, so there is a premium on habitat diversity; (iv) invertebrate life cycles are short, so populations can fluctuate immensely from year to year, and even a short break in suitable conditions can eliminate a population; and (v) many species have poor powers of dispersal, so cannot escape catastrophes and temporarily unsuitable conditions, nor can they recolonise easily. Habitat fragmentation thus presents great problems, for this isolates populations and inhibits recolonisation. Fowles also noted that the niches of many species are associated with early stages of succession in new or disturbed habitats (such as freshly exposed river banks) or late stages in mature habitats (such as ancient trees), but most semi-natural habitats are neither young nor mature, but somewhere in between.

Against this background, the rich and exciting fauna of Moccas Park must be due to three main factors. First, it contains (and has always contained) a large number of old trees with decaying heartwood, which have allowed the ‘saproxylic’ species that used these habitats in original forest to survive. Second, it includes the Lawn Pool and other wet ground that provides refuges for species of another much-reduced habitat. Third, as a parkland, it has maintained an intimate mosaic of grassland, heathland and trees, with a great diversity of niches, from deep shade to open ground.

Woodlands

The saproxylic species are significant because they were far more diverse in the original natural environment. This was exemplified by recent studies of animal remains associated with prehistoric human activity at Goldcliff (Smith et al., 2000), which included beetle species – including the saproxylics Corticeus unicolor, Colydium elongatum, Prionyhus melanarius, Bolitophagus reticulatus and Drycoetes ulmi – that are normally associated with old growth and especially large open-grown trees, but which are now rare in Britain. Keith Alexander tells me that C. unicolor is today confined to small relicts of the former Sherwood Forest, B. reticulatus is only found in the Caledonian Forest relicts, while C. elongatum is a speciality of the New Forest and Savernake Forest. In contrast, P. melanarius remains fairly widespread in the Severn Vale, whereas D. ulmi is now extinct in Britain. This is just one local example of a widespread finding, that species associated with large trees and deadwood were common and widespread prehistorically, but are now either extinct in Britain or confined to a few places where they appear to have survived as relict populations due to continuity of their specialised habitat. In Britain, Windsor Forest and Park and the New Forest are by far the most important locations for saproxylic beetles, but Moccas comes third, and the Forest of Dean and Lydney Deer Park come within the top 100 sites (Alexander, 2003). If, as it seems, continuity of mature and dead timber is the key requirement, Kentchurch Park may also prove to support relict populations.

Moccas is famous for the Moccas beetle, Hypebaeus flavipes, which was found in 1934 and is still known from nowhere else in Britain (J. Cooter in Harding & Wall, 2000). The oak in which it was first found was re-identified in early 1975 and further specimens were found on it in July that year, and it has since been found on several other oaks in the park, all with red-rotten trunks. It is widespread but rare in Continental Europe, where it is invariably associated with large and rotten oaks and beech. Other rare saproxylic beetles include Ampedus cardinalis (a click beetle), Pyrrhidium sanguineum (a carmine-red longhorn beetle known only from a few places in the southern Welsh borderland), and Ernoporus caucasicus (the lime bark beetle) (R. C. Welch in Harding & Wall, 2000). The last was not recognised until 1969, fifteen years after it had been collected in 1954 and eight years after the only tree from which it was known blew down (sadly, the wood was removed and burnt). However, it has since been found in several other sites and on other limes in Moccas. Ten of the Diptera species are also rare saproxylics (A. Godfrey in Harding & Wall, 2000). These and other saproxylics are associated with large, usually ancient broadleaved trees, need nectar sources, and have very precise requirements in respect of tree species, age and state of decay. The park remains internationally important for the concentration of rare species, though there are indications that populations are falling, which, if substantiated, would be due to the declining number of ancient trees and removal of deadwood.

The Fiddlers Elbow area is also famous among coleopterists for the fleeting appearance of the net-winged beetle, Platycis cosnardi, in 1944, a relict species of old-growth beech forest. According to Keith Alexander, it was reported by Miss L. Lewis on 6 May in a garden surrounded by woods containing some very old oaks and beeches ‘on a stone, with elytra open, either at rest or dead’. Another, half as large again (evidently a female), flew onto some botanical paper in the garden on 29 May, and possibly a third flew through the garden on 24 June. It has not been seen again in the Lower Wye, but it has since been found on two occasions in areas of old beech on the South Downs. Perhaps a small population remains at large somewhere in the Highmeadow Woods.

Lady Park Wood, as a stand that has been allowed to revert to old-growth (Chapter 5), might be expected to hold many saproxylics, and indeed surveys of beetles and flies by Keith Alexander and Dave Gibbs, respectively, have found a good range of uncommon and rare species. One was Tanyptera atrata, a nationally scarce cranefly, the larvae of which develop in decaying logs and fallen trunks of various broad-leaved trees, mainly birch, in relict old forests. The Gloucestershire part of the Wye Valley holds several other saproxylic Diptera, including Brachypalpus bimaculatus, Criorhina ranunculi and C. pectinicornis. On the Monmouthshire side, Ernoporus tiliae, another deadwood specialist, was found recently on lime at the Wyndcliff (Ecotype, May 2006). The mildly alarming stag beetle, Lucanus cervus, survives in Monmouthshire.

Grasslands and heaths

Grassland invertebrates seem to be even less well known than those of woodland. Meadow faunas are poor, for, as Fowles points out, their invertebrates suffer an abrupt loss of shelter, food and breeding sites when the hay is cut. One good site is Brockwells Meadows, a small area of cattle-grazed unimproved grassland on Carboniferous limestone and Triassic sandstone, which was owned and farmed by Colin Titcombe’s family for 40 years. In addition to some local butterflies, this site supports great green bush-cricket and the very local hornet robber fly (Fig. 184). This species sits lazily on cowpats, a habit that allowed Clement and Skidmore (2002) to carry out a detailed population study. They found that the fly was restricted to a 2ha slope in the largest field, where the population in July and August was estimated to be just 51-104 individuals. Marked individuals were found to move up to 125m in a day, which was not enough to carry them to other patches of suitable habitat. This is therefore a classic example of an isolated population that is highly vulnerable to, for example, a change in pasturage from cattle to sheep. Another vulnerable population is the yellow hill ant at Moccas. This was formerly widespread in the park, but it was reduced to small, scattered colonies when the grassland was ploughed and reseeded (Harding & Wall, 2000).

Another declining group of invertebrates is the wild bumblebees. Until 50 years ago the Lower Wye probably supported 18 wild species, but several species have latterly been much reduced or eliminated (Prys-Jones & Corbet, 1991). Consider two species that are associated with herb-rich grasslands, such as semi-natural hay meadows, the shrill carder bee and the brown-banded carder bee. Both were widespread, but never abundant, but now they have been forced to

FIG 184. Hornet robber fly, which survives as a small, isolated population at Brockwells Meadows. (Photo: Colin Titcombe)

retreat mainly to southern coastal districts. In Monmouthshire, the former was very localised on the Gwent Levels in the 1990s, and recent searches for the latter in the Lower Wye by Andrew Nixon located just a single population near Llanishen.

CONCLUSION

How natural is the fauna of the Lower Wye now? The mix of species that the Mesolithic hunters would have noticed has clearly been transformed. Not only have aurochs and other large beasts been eliminated, but the species associated with mature woodland, ancient trees and rotting wood have been reduced to small, scattered, relict populations, if they have survived at all. True, some have adapted, such as bats (which have moved to roofs), swifts (from nests in hollow trees to eaves) and beetles (some of which now bore into timber-framed houses), but most have not. Until recently, the tree-species’ loss was the open-habitat-species’ gain, for the fauna of open forest, glades, heaths and marshes expanded to fill traditional farmland, but these too have been much reduced with the modern intensification of farm production. Even so, the majority of the species currently inhabiting the Lower Wye would probably have been present in the prehistoric landscape, albeit in different proportions and patterns. For millennia, the wild fauna has been changing in response not only to changes in land use, but also (as the butterflies and birds are showing) in response to global changes in climate.