ON the day that the main column marched north again, forty of us were taken out and sent to a village called Munha-ri, two miles to the south. Our party was a mixture of fairly fit men and invalids, so that with dysentery an ever-present danger to every one of us, to say nothing of all the other diseases with which Korea abounds, we were delighted to find Bob among us when we formed up to leave the the Half-way House. To my great disappointment, I was separated from Spike.

Munha-ri was quite a small village of no more than forty houses, lying below and up the side of a hill standing a quarter of a mile back from the Taedong River. To our great surprise, We found the remnant of Sam’s column was in the village—mostly sick men, but including the Padre, our Gunner Battery Commander, Guy, and an American Air Force pilot, Duncan. Another reunion took place.

A new schoolhouse had been partly built near the river, the walls still unplastered, the windows unglazed, and the doors unhung. We were all crammed on to the dirt floor in a concentration which just left us room to He down at night. A new routine commenced. Before dawn, our guards would begin to scream orders through the window in an effort to get us out of bed. Eventually, the fit would rise and form up outside for a check, preparatory to marching off. The hours of daylight would be spent on a hill about a mile away where, in the shelter of a pinewood, we received our breakfast of kaoliang—on three wonderful days, we had rice, as a treat—and half-cooked bean shoots. The two Chinese doctors in the village occasionally came to the schoolhouse to examine the sick and, now and again, gave Bob a few drugs to dispense. As the number of sick increased, we were told that it was due to our neglect of “personal sanitation”—for which they held no responsibility. They were quite unabashed when Bob pointed out that we were rarely allowed even to wash our hands and faces. Eventually he was permitted to remain behind each day to care for the sick, though the issue of drugs remained irregular, infrequent and inadequate.

On our first evening in the village we had been addressed by the guard company commander, a small, dapper, young Chinese, who called himself Tien Han. Through a pudding-faced female interpreter, he pointed out to us that though we had been spared death at the hands of the Chinese, we must not mistake this leniency for weakness. We were war-criminals who would now be given an opportunity to make recompense for our past misdeeds; absolute obedience to his authority would be the first way in which we must show that they had been justified in sparing us from death. Those who disobeyed the regulations must expect, at least, severe punishment in the form of rigorous imprisonment.

This little address was followed a few days later by a military interrogation. The only officer who was questioned seriously was Carl, whose identity as a technical expert they suspected, though, by good fortune, they never discovered that he had commanded a radar unit. Carl was brought up before the principal interrogators three times, and, remaining obdurate in the face of their threats, was bound and marched away to a small underground bunker where he remained night and day for a considerable period. He was not the first to be placed in this foul, deep hole. One of Frank’s young Gunners, Ross, had already served a sentence in it, becoming so ill from the damp that he had contracted severe bronchitis. Sergeant Sharp, the Intelligence Sergeant of the Fifth Fusiliers, soon joined Carl and we began to wonder which of us would be next.

I became convinced that the fact that I had argued politics with Chen had been reported to the headquarters controlling Munha-ri. On the first occasion that I was taken out, I was asked:

“Where did you receive your political training? Are you a political officer with your Army? Did you give political instruction to your unit?”

And when I made no reply to this, they said:

“What is it that you misunderstand about Marxism that makes you reject it?”

These questions were asked me by a very ugly, lisping Chinese called T’ang, who spoke English with a heavy accent. He was an unpleasant and dangerous character, ambitious to a degree; a man who boasted that, as the son of a landowner before the revolution, he had subsequently delivered both his parents into the hands of the authorities for execution as “enemies of the people”. I was taken out twice, about this time, for an interview with T’ang, and spent most of the time listening to his opinions on international affairs and the change that might be expected in these now that China was becoming the most powerful nation in the world. They soon became tired of military interrogation and began to select small groups of prisoners to attend lectures on the Chinese Revolution and its significance. As an alternative, we had further addresses reminding us of our good fortune in having our lives spared; of the debt we owed to our Chinese captors for their “lenient treatment.” They cannot have realized how bored we were at hearing the same nonsense repeated over and over again.

My foot was now healing fast, thanks to Bob. We made up a new escape party consisting of Bob, Thomas, the Filipino, Sid of the Fifth Fusiliers, and myself. Byron, the Marine, was also a member, as soon as Bob pronounced his burns sufficiently healed. Unquestionably, bis former health had pulled him round, in spite of the absence of drugs and surgical treatment It was only later, after our strength had been sapped by long imprisonment, that we were to find it impossible to recover fully after sickness.

We went over our plans as we sat on the hillside each day, making what preparations we could from our limited resources. Just as we reached the point of being ready to go, Bob had to withdraw. It was at this time that he was allowed to look after the sick and wounded in what he called the “mediaeval pest-house” and he felt that he could not leave them to the mercy of the Chinese. It was a bitter disappointment to him—indeed, to us all. We prepared to go without him. Then the final blow fell.

One evening, after the second meal of the day, T’ang came into the schoolhouse and read out a long list of names, telling each man to move outside with his few possessions for a night march. When he had finished, we discovered that five of us were to remain in the village with a group of very sick men and the occupants of the bunker: Sergeant Sharp and Carl. This was a new Chinese puzzle which we were to spend many weeks in trying to solve.

Our little group returned to a house at the river end of the village, in which we were allotted a small room. Now, instead of leaving the village entirely for the hours of daylight, we were merely taken to the hill at the back of our hut where we lay under the trees. Each one of us had lost friends in the departure of the other column and I had lost all my escape associates. Our group consisted of Guy, the Padre, Duncan, Sergeant Fitzgerald of the Gunners, and me; and what we were all doing there was a mystery.

A possible solution to our retention in the village occurred on the fifth day after the column had left. On the afternoon of this day, we were bidden to the quarters of the guard company’s officers and sat down to afternoon tea. This consisted of bowls of hot water being passed round, each of which contained about three green tea leaves which left the water lightly coloured but tasteless. Still, we were not even used to hot water at this time of day, and we were most curious to know what had occasioned this move. A packet of cigarettes was produced and passed round. We all smoked. Smiling, showing his perfect teeth in an affected way that he had, Tien Han, the company commander, addressed us through T’ang.

“All the others have gone except for the five of you and some very sick men. Undoubtedly, you are asking yourselves, why has this happened?”

The EDGE of

the SWORD

PICTURE SECTION

1. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff visiting the Glosters at Colchester immediately before their departure for Korea. From left to right: Field Marshal Sir William Slim, Lieutenant-Colonel J.P. Carne, Captain A. H. Farrar-Hockley, Major P. W. Weiler.

2. The Glosters embark for Korea, September 1950. They are boarding the Empire Windrush at Southampton.

3. Major P.A. Angier, killed in action commanding A Company.

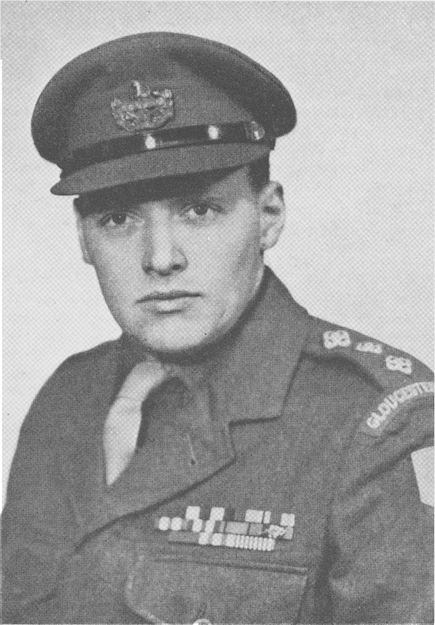

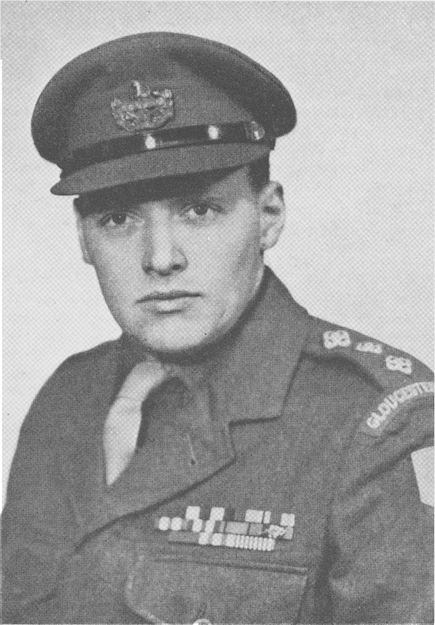

4. Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley, D.S.O., M.C.

5. Drum-Major P.E. Buss at battalion headquarters with CSMI Strong (back to camera), Colonel Carne’s escort, and Sergeant Baxter RAMC.

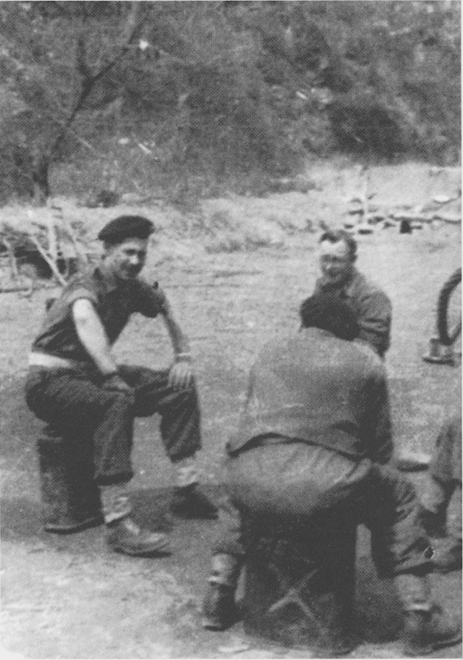

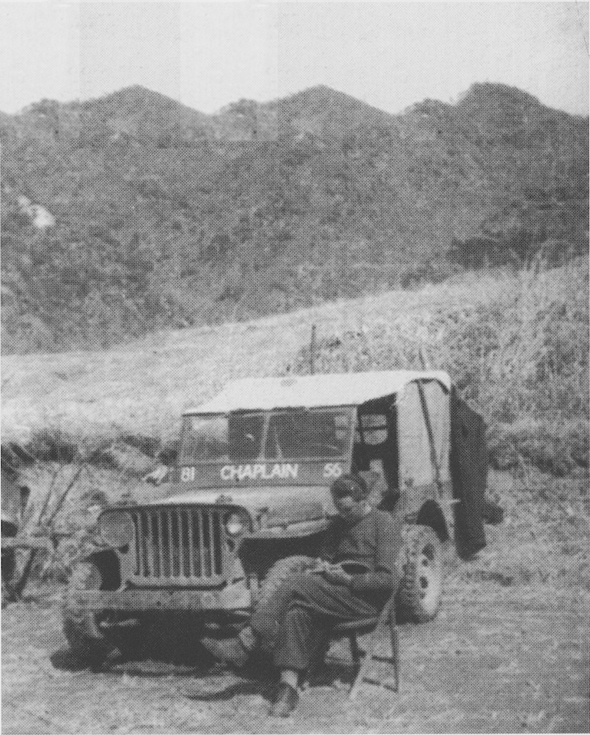

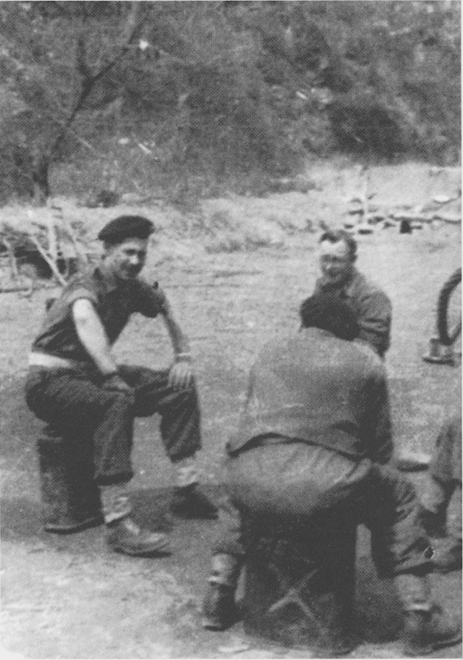

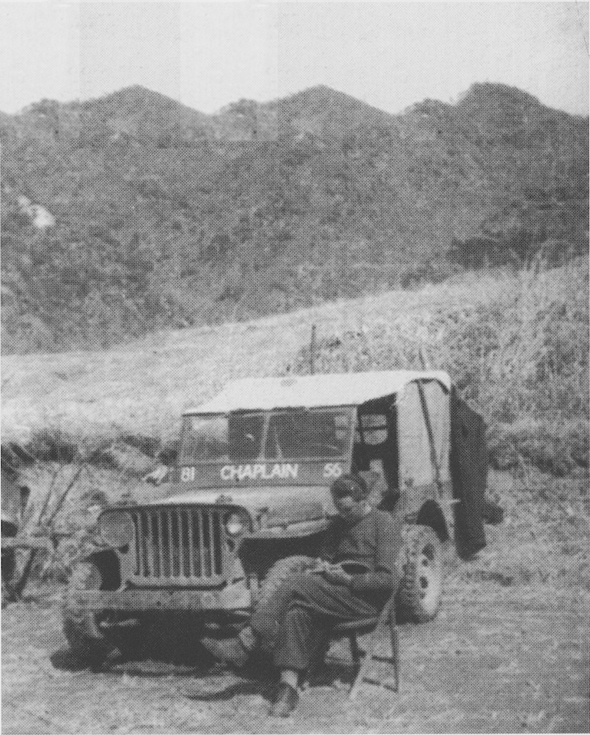

6. Padre ‘Sam’ Davies at battalion headquarters, April 1951. The peak behind is Kamaksan.

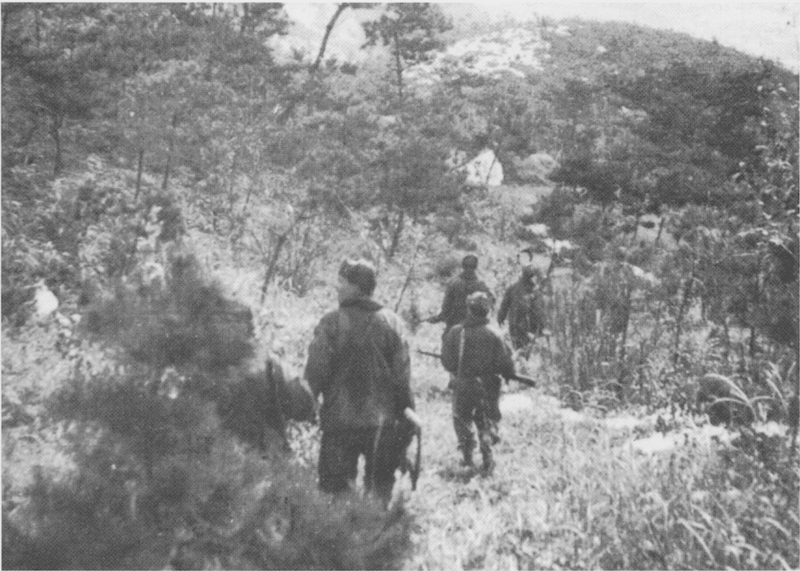

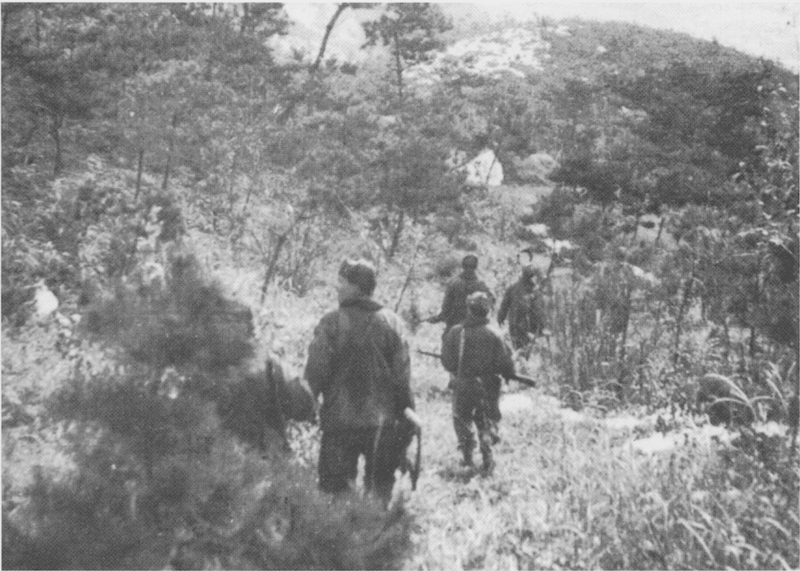

7. A Glosters patrol on the Imjin approaches.

8. Imjin crossing – taken after the sortie by the Battalion and 8th Hussars across the river, 18 April 1951. The C Company ambush on the night of 22 April was mounted on the cliff tops on either side of the track.

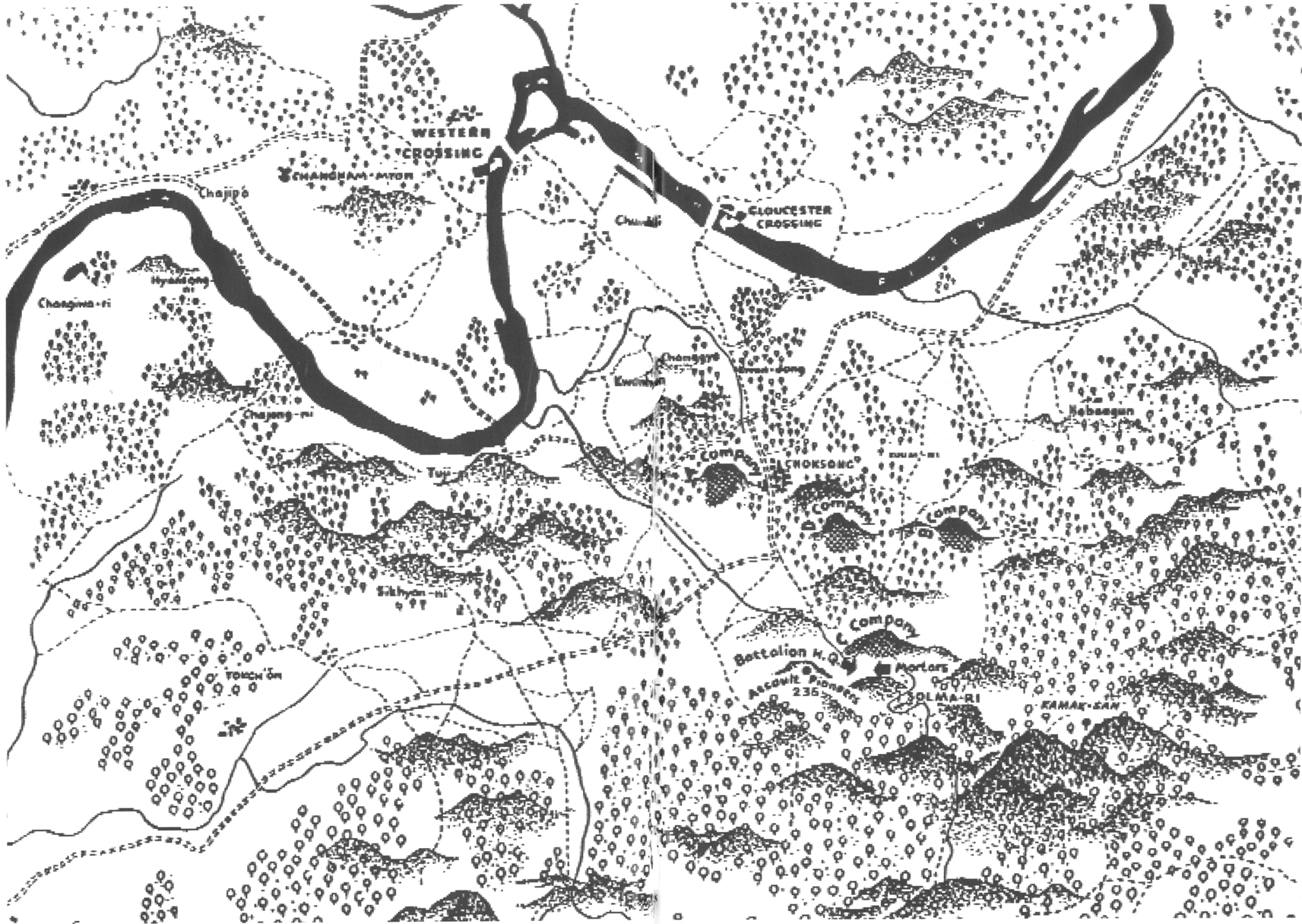

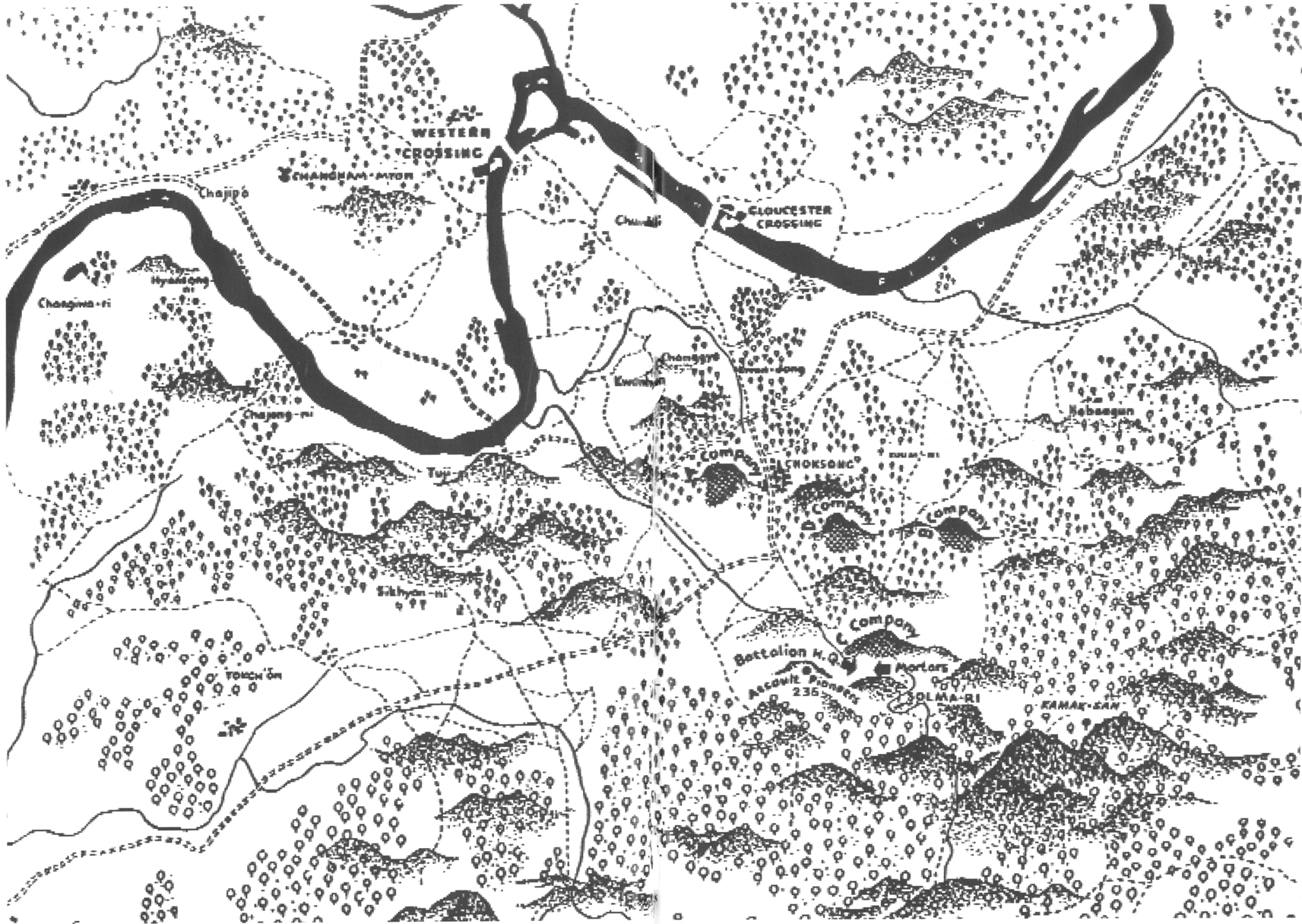

9. The Imjin river and surrounding area.

10.View from Hill 235 towards the Imjin River.

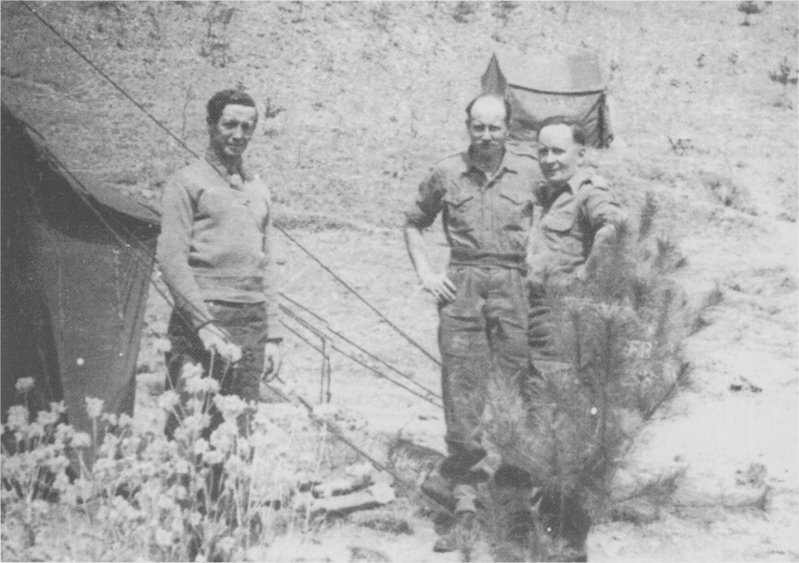

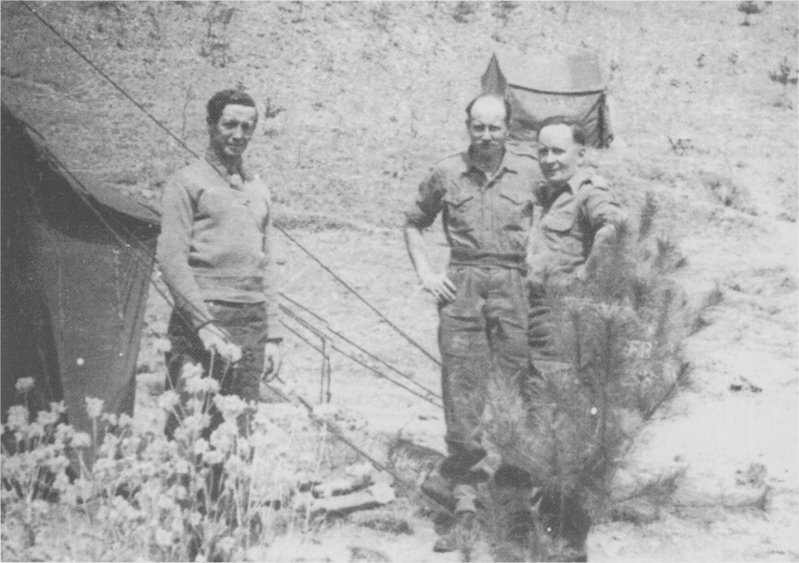

11. (Left to right): Captain R.P. Hickey, Regimental Medical Officer; Major P. Mitchell, commanding C Company; and Major D.B.A. Grist, Second-in-Command, just before battle.

12. Bringing down the wounded. Four, sometimes six, men were required to carry a stretcher down the steep slopes of Korea.

13. The ascent to Hill 235, on which the final stand was made by the Battalion.

14. After the Imjin River battle, the few Glosters who escaped entrenched themselves in new positions.

15. A picture of Glosters prisoners taken on the line of march to prison camps. It was produced by the Chinese as a token of response to demands by the United Nations for names and details of circumstances of those captured. A number were identified by relatives.

16. Those who got away: survivors of the Battalion muster for a roll call, 26 April 1951

17. Before his capture –‘Spike’ (Captain H.J. Pike), who later helped to carry the author on long night marches.

18. After twenty-eight months of captivity – the author at home with his wife.

19. Homecoming – the ‘Glorious Glosters,’ led by Lieutenant-Colonel Carne, V.C., march through the streets of Gloucester.

We waited expectantly, wondering what was coming.

“We Chinese do not wish to be your enemies; we are your friends. It is your own leaders who are your enemies but you do not understand that yet. In time, you will come to have a full understanding of this problem. You require a great deal of education. In the meantime, if you have any doubts or worries, come to us to solve them. You may approach us at any time.”

That was all, except to ask us to sing a national song of ours to them; an invitation we declined, though Guy was pressed so much towards the end that I felt sure he was going to oblige with “Screw Guns”. We never attempted to follow up the proposal that we should approach them to discuss our “problems”, whatever they might be; and, equally, for some time, they made no effort to contact us, except for the normal daily routine.

Then T’ang began lecturing us—the five fit as well as the sick men—on the subject of what he called “The New China”. Each morning, he would appear, lisping and smiling, a changed personality from the scowling Chinese he had been less than a fortnight before. His scowl returned only once, in fact. One warm afternoon, we were sitting in the June sunshine on the hill, drowsing, as I recall it, when he suddenly appeared from nowhere like the Genie that materialized from Aladdin’s wonderful lamp. In a shaking voice, his face twisted with rage, he pointed to the bound figures of Bob, Byron, and Thomas, who had been brought up the hillside.

“These men,” he screamed, “tried to escape from the group marching north. But escape is impossible! We Chinese are all-powerful; you cannot evade us! Now these men will receive the severe punishment they deserve.”

He led our three friends away, and we returned to our places, desolate that they had been recaptured.

Carl, Bob and Thomas were released three weeks later from their respective bunkers, and we had every hope that they would release Byron and Sergeant Sharp before very much longer. By this time, we had had a council-of-war about our position. We had very little to go on—Tien Han’s little speech, certain hints dropped by T’ang, a few allusions to “study” made by Kan, T’ang’s deputy. There was not really enough evidence to form an opinion as to the meaning of it all; but we decided that we must have a firm policy in case they started political indoctrination in earnest.

We knew from our own intelligence sources, prior to capture, that the Chinese and North Koreans had returned small batches of prisoners after lecturing to them for a time. I recalled that three of our men had been returned in February after capture in the New Year battle of the Rifles. Furthermore, they had received their “course” at a political school north-east of Pyongyang—the direction in which Munha-ri lay. Was this the school, we asked ourselves? If it was, what was our position? The real question came to this: if we felt that there was any prospect of our being sent back to our own lines, having the information we possessed about the battle, about the conditions along the line-of-communication, and about the treatment of prisoners, should we be prepared to listen to the seditious matter which would be put to us in the form of political lectures? My view was that we should listen to as much as they cared to give us, provided that we were not required to sign anything, write anything, record, or broadcast, or give lectures ourselves. We were all of the same mind, agreeing to suspend our escape projects for the time being. When Carl, Bob, and Thomas joined us, we put the same question to them, and they agreed with the policy. This was our outlook, then, when T’ang began to lecture us on the origins of the Korean war and the guilt which lay upon the shoulders of the Government of the United States. We sat down to listen, obediently, assuming expressions which we hoped would convey interest, surprise, even—when the worst accusations were made against our own Governments—horror. There were to be times when we required every ounce of self-control—sometimes to prevent us from assaulting the lecturer; sometimes to prevent us from bursting into screams of laughter! June ended, and July still found us sitting on our portion of the hillside, waiting to see what the next move of the Chinese would be.

As the summer advanced, three major incidents disturbed the dull routine of our lives. The first was that T’ang left us—“on promotion to a higher command”, he said, smirking—and Kan became our lecturer-in-chief. Next, as Byron was released from the bunker, Bob, Sergeant Sharp, and all the sick party were sent north by truck, leaving Duncan, Guy, Carl, Thomas, Byron, the Padre, Sergeant Fitzgerald and myself. Last, Tien Han’s company was relieved from duty in the village by the same company that had taken the Colonel’s column north—the company of Commander Soong, whom we called “Mephy” because of his Mephistophelian eyebrows. Amongst the company officers who now supervised our life, the principal English-speaker was the pig-faced youth who had met me on the night that Kinne and I joined the Colonel’s group in the south.

Kan, who belonged to the Regimental Headquarters, continued to visit us each morning to give his lectures, to bring political material for us to read, and to labour at the thankless task of getting us to work up a really good group-discussion on such themes as “The course of imperial aggression in the Far East since 1945.” Somehow—though we tried so hard—we could not manage the right note of sincerity. In retrospect, I see that Kan came to realize little by little that our hearts were not in our work; that we took part in his classes only as a means to an end. By the time that August had arrived, his smile on parting rebuked us for not really wanting to be converted to Marxism: he could not understand us at all.

I became more and more impatient to see the end of the game that both sides were playing, so that I should not lose an opportunity to escape before the summer months were over. Carl felt the same, but was certainly not fit to try at that moment: he had contracted dysentery, which the few tablets the local doctor was prevailed upon to give him from time to time did nothing to cure. I, too, had been weakened by a bout of relapsing fever; a deceptive disease causing a high temperature, which apparently leaves the body only to return again with renewed strength four or five days later. The Padre’s presence was a great comfort to me at this time—both spiritually and materially. He, Carl, and Byron washed my sweat-soaked clothes in the river during one hot day; and, strangely, when a third bout of fever was beginning, it left me as he said the prayer for the sick and laid his hands on my head.

I began to do simple physical-training exercises with Carl as soon as I felt better. Our diet had certainly improved, in that we now had potatoes, cabbage, or pumpkin to eat with our kaoliang. Twice, we had a wonderful flour and water pancake fried in bean oil. On the second occasion, Guy was caught by a guard hiding some extra ration of these under an old sack. He hastily explained that he was merely trying to keep the flies off them, but couldn’t find any flies about when he was asked where they were!

We had been in Munha-ri nearly three months, when we were given notice to pack up one evening in late August.

In the middle of the guard company, accompanied by Pig-Face, the interpreter, and Chang, the company officer who had immediate charge of us, we set off from Munha-ri about an hour before the sun set. We were all tremendously excited; for we felt that, at last, with August almost over, we were going to discover why we had been kept back from the prison camps in the north. Besides, we were all sick of Munha-ri: sick of being harassed by the boy guards of sixteen and seventeen, whose hatred of us was stirred up daily by the company political officer; sick of the patch of hill we had been confined to for so many weary weeks; sick of waiting about to see what the Chinese were going to do next. As the leaders in the column took the path that led south from the village, eight hearts rose in eight breasts: south was the course, not north! Perhaps, after all, we really were going back to the front. With every step my hopes for an end to captivity increased; for if the long shot—release by the enemy—failed, every yard along our present course improved my chances of escape.

We fell into the familiar march-routine: breakfast at dusk and supper at dawn. Another series of villages provided billets for the column during the daylight hours. And all the time, our general direction continued southward.

We marched through the broken streets of Pyongyang, causing a mild stir, as our bearded unkempt figures were noticed by one and another of the groups in the crowded street. The population seemed to consist mostly of North Korean soldiers and workers—though we saw two cars carrying Russian military and naval personnel, who, we assumed, were part of the local Embassy staff. There were several European civilians, too, who quickly turned their heads away when they saw us. In the central area through which we marched, no more than thirty Chinese troops passed us, except for the many convoys of supply vehicles that awaited passage across the one bridge in operation.

Beyond Pyongyang, we took the road south-east that leads, eventually, to Suan. To our delight, Pig-Face, who was forever boasting of his courage and belittling ours, began to show his apprehension, as we marched along roads subject to air attack by our night bomber forces. The effect of his fears upon us was that he became more than usually unpleasant, removing our food before we had finished, on the excuse that we must get ready for the night march without further delay; preventing us from washing in a nearby stream, with the accusation that we were trying to signal to aircraft—when there was none to be seen or heard; and instructing the guard to prevent us from leaving the room in which we were confined, so that we could not go to the latrine. Of the many ways in which he could vent his spite on us, surely the worst was his habit of preventing us from resting in the mornings on those days when he had overeaten himself and was thus suffering from a bilious attack.

On the eighth night of the march, the column scattered from the road as the sounds of aircraft were heard close by. Everywhere the air-raid warning “Fiji—fiji-lella” went up, as we took cover on a boulder-strewn hillside. Some way down the road, one of our planes was firing its machine-guns beneath the light of parachute flares. As the last burst died away, another sound caught my ears. With the greatest pleasure I saw a pale, terrified Chinese lying near me in the ditch. It was Pig-Face being violently sick!

Ten days after we left Munha-ri, we reached our destination.

We had lost our way that night, as usual—not once, but many times. When, finally, we reached the rendezvous at a turning off the main road, the guide had forgotten the route by which he had come to meet us. In the pouring rain we stumbled through streams and rivers, up and down hillsides, in and out of valleys, inquiring at every village and hamlet through which we passed. It was almost dawn when we halted by a group of houses. The guards began to remove their packs with many mutterings of “Ta malega”—which is a very rude word in Chinese.

“This must be it,” said Duncan, who, being an airman, hated the marching even more than we did.

“I won’t believe it,” said Carl, who was now walking in boots without soles.

But it was. We had arrived at the village which was to be our new home.

Having divested themselves of their packs and other equipment, our guards led us into the courtyard of a medium-sized Korean house, where the Company Headquarters’ staff, already settled in the rooms, seemed to have filled the entire building. At that moment, Chang appeared with Pig-Face, indicating that we should enter two small storerooms, each about the size of a water-closet in an average British semi-detached house. The only way in which four of us could lie down simultaneously in one of these rooms, was to overlap legs and hips, taking it in turns as to whose legs should be on top! Carl, Byron, Duncan, and I settled in one of the boxes and were soon asleep after an exhausting night.

The weather had improved by the following morning, and we were able to dry out our damp clothes—already partly dried by the heat of our bodies. Apart from Carl’s boots, we were not too badly equipped at that time: I had a pair of Chinese shoes; we each had one of the small handtowels the Chinese issued to their soldiers, a piece of soap, and a toothbrush. These articles had been given to us, with the explanation that we were not prisoners-of-war but merely uneducated fellows—backward boys, really—to whom they were trying to teach the truth. We had accepted the items without comment.

Another hillside gave us accommodation during the day from now on; a duller hillside than that at Munha-ri: it had no view beyond a few hundred yards of maize fields. The days passed as we sat waiting for some explanation or statement from our captors concerning the move and their intentions for our future. Nothing happened. Four days went by without a sign of Kan, Chang, or even Pig-Face. We urgently needed the quack who served the Regiment as a doctor, and occasionally favoured us with his presence. We saw him in the distance once and called to him, but he hurried away as soon as he saw who we were. On the fifth day, Pig-Face appeared. We showed him Fitzgerald’s feet, which were cut, and swollen with pus. Byron and Carl needed the doctor, too; their dysentery was considerably worse. Pig-Face reminded us that we were captives—perhaps he had forgotten we were “backward boys”—who were unentitled to medical treatment. For good measure, he told us that the peace talks, of which Kan had given us a very little news just before we left Munha-ri, had been broken off, and that the Chinese were now moving steadily south in a great offensive. He had so many unpleasant things to say that, after he had swaggered off along the path, we made a pact that we would ignore him in the future—a policy that was to achieve some success in irritating him. Meanwhile, we had to consider how things stood, in the light of his news about the peace talks.

We had never been very sanguine about these—Kan’s information had made it plain that his side were out to wring every ounce of propaganda from them. It had occurred to us that the talks might enhance our prospects of return: the Chinese might want to give an appearance of good faith, by releasing a number of prisoners during the early stages of negotiations. Unless Pig-Face was lying—which was very possible—any hope of this had now disappeared. That day I decided I would begin preparations to escape, so as to be ready to meet any eventuality. My immediate problem was a partner.

Because of sickness or debility amongst the others, I decided that I would ask Duncan. He was a man of very strong character who, having put his hand to the plough, would not readily turn back. He was an unselfish companion, had a strong constitution, and, not least, was a good swimmer. That evening, I spoke quietly to Duncan, as we lay side by side in the box we shared, the only time when we were not under permanent observation by the guards. Duncan still believed that we had a prospect of release. Once he knew that there was no hope, he was ready to come with me, he said. I told him that I was already at work on my means of escape and would wait another three days. After that, I should have gone. He had three days to decide on what he wanted to do.

Two evenings later Kan appeared with “Hawk-Face”, the Regimental Commander, and “Pudding-Face”, the girl interpreter. Hawk-Face said how well we all looked. We must be careful not to get too fat! We were fatter, he declared, than when he had last seen us—what excellent care the company was taking of us! He looked into our accommodation and remarked that we were indeed lucky. He might have been Mr. Rackford Squeers, inspecting the school. I almost asked him why our kaoliang ration had been cut, why we had no doctor or medical kit for Fitzgerald and the others, and why we were treated like felons, instead of honourable prisoners-of-war. But I forbore; there were other things I wanted to ask Hawk-Face.

“We are very sorry to hear that the peace talks have been broken off,” I began. It had to be put like that. To have asked a question would have been fruitless; he would merely have replied with the blandest of smiles that he did not know, he had not heard.

Hawk-Face glanced at Kan for a moment, then nodded. Kan muttered something to Pudding-Face.

“Yes,” said Pudding-Face, “it is a setback for the true lovers of world peace everywhere. Now the world can see that it is the American Imperialists and their lackeys”—she added this for the benefit of her British audience—“who are the enemies of the people. You will see it, too, if you study.”

Hawk-Face intervened here; he spoke quickly to her in Chinese and at some length, using his left hand to emphasise a point as he developed his subject. At last, Pudding-Face turned back to us.

“Go to your sleep, now,” she said. “You need this for your health; you must take great care of your health, the Regimental Commander says. You have not worked hard at your study of the truth. You must now begin to study with sincerity. You should write a letter to your friends at home, telling them to act for peace in Korea. Soon, perhaps, you can pass on the truth to your friends in their camps in the north.”

They bade us good night and we climbed into our sleeping boxes. I had heard enough to convince me that I had waited too long. When all was quiet, I paused in my work, and turned over to Duncan.

“What about it?” I whispered. “Are you coming?”

“You’re damn right, I’m coming. When do we start?”

On the following night, my preparations bore fruit: Duncan and I slipped away from the village, heading west under a quarter-moon. We hoped never to see Pig-Face again, except at the end of a rope.

As the sun rose, we settled ourselves on a hill-top under the cover of the dwarf oaks and prepared to rest, having breakfasted off raw maize. We took it in turn to watch, the first turn falling to me. Lying there, listening to the noises that rose from a village far below, I realized that my whole body was filled with that splendid feeling which I had lost months before at the monastery: freedom! We had a long, long way to go and there were many difficulties to be overcome—not least, our physical weakness—but we were free again, and our anxiety to retain our freedom would strengthen us in every adversity.

Each night we moved as directly along our course as we could: the route was never easy. The hills were covered with bushes and dwarf oaks, which gave us splendid cover by day but impeded our movement by night. Many of the valleys contained rice fields which were flooded at this time of the year. We had to avoid main tracks, choosing, when possible, fields of maize or soya beans for our path, yet leaving these deliberately at intervals because of the clear trail that our passage unavoidably left in them.

On the fourth night we came to a river that lay directly across our route. We could not see the other shore. Searching for a ford, we set off along the bank and, a mile downstream, found a sandbar stretching into the river, thrown up by a small stream which emptied here into the main waters. There was just a chance that the river had silted up sufficiently at this point to permit us to walk across. We walked along the spit to the water, wading in. The ground dropped away beneath us, the water reached our waists, our chests, our shoulders. The current caught us; there was no going back. Remembering my previous experience in the Imjin River, I turned on to my back as I was swept away, keeping my arms under water, and kicking strongly with my feet, I was getting tired when my anxious foot touched bottom on the far side and I found that I had reached the base of an almost sheer cliff. I was about to leave the water when I heard Duncan’s voice.

“Help!” he called. “Help! I’m drowning!”

Wading towards him, I saw that he was only a few yards from the shore.

“It’s all right,” I called back. “You’re in shallow water. Stand up.”

Doubtfully, he put his feet down to find that the water came up to his armpits. We met by the bank. It appeared that he had found the weight of water-filled boots too much for him—he still had his original leather pair—and, making the mistake of trying to take them off while swimming, sank, swallowing a great deal of water, as he began to sink a second time. He had come up for the third time when he called out. The shock and the cold river had set him shivering uncontrollably. I was feeling the cold also, but the scramble up a nearby re-entrant, that was very steep and filled with thick bushes, helped to restore our circulation. It was beginning to get light as we found ourselves near a wide track, bearing the imprint of tyres. Obviously this was no place for us; it was time to find a hiding-place for the day. We hurried away from the road and through a cultivated valley, made a detour of a village, and began the ascent of a hill. Half-way up we came across a series of platforms such as the Chinese dug out for themselves to sit on during the summer days. Above these, the hill was fortified with trenches and dug-outs, but they looked old and unused; the trench walls were falling in, many dugouts were flooded. The whole system had probably been dug during the withdrawal of the enemy to the Yalu the year before. It seemed unlikely that we should encounter troops here at this time, so we climbed on to the crest of the hill. In any case, it was well after dawn; it would have been difficult to get to another hill, unobserved by those in the many villages that we saw in the valleys on either side.

Our clothes were still saturated with water from the river crossing; there had been no time to wring them out. Unfortunately, it was an exceptionally overcast day and the strong wind was from the east. I squeezed the water from my outer garments and dressed again. Duncan, however, laid his things out to dry, clothing himself in his thin flying suit as a temporary measure. We were both feeling the effects of our long and tiring marches, the coarse food we had been given over so many months, and the uncooked maize which had done little more than ease our hunger pangs during the past three days. I decided that we must try to obtain food which would sustain us against the ten or twelve days of arduous marching that separated us from our destination, the coast. While Duncan was laying out the remainder of his clothes so that they would not be seen from the village below, I went off along the hill to select a house from which we might obtain sustenance

At the head of the valley that lay to the east of our hill I saw a small isolated house from whose one chimney smoke was rising. A path ran past the house, joining a wider track as it approached the village that stood on the valley floor—a village that was filled with Chinese soldiers. The advantage of the isolated house was that Duncan and I could descend the hillside under good cover to see who lived in it, and Duncan could watch the path for half a mile in either direction while I entered to seek food, if a civilian family were in occupation. We followed this plan exactly.

The moment came when I approached the open kitchen door, through which we had seen a young woman cooking at one of the pots. The kitchen darkened as I stood in the doorway, causing her to look up. I smiled and showed her that I held no weapon in my hands. Still watching me, she half-turned her head and called to her husband who was lying on a mat in the other room. She must have said something that alarmed them all, for the cries of the two children with whom he was playing ceased. For a moment all was quiet. Then he got up and came into the kitchen. From the doorway I looked down into their frightened brown eyes.

I made signs that I was hungry and pointed to the cooking pot. The man said something in Korean to me which I did not understand, adding,

“Migook?”—American?

I shook my head. “Yungook.”

They continued to stare for some moments; then the man pointed to my eyes, turned to his wife, and laughed. She smiled. They had probably never seen a man with blue eyes before. On this basis of humour, the man seemed to become friendly. He spoke to his wife, who began to scoop up their breakfast from the cooking pot. At the same time, he joined me by the door and pointed down to the village.

“Chungook,” he said. “Na pa.” I was encouraged to find that he had a poor opinion of the Chinese; I felt bound to agree with him.

By this time, his wife had removed everything from the cooking-pot. With a feeling of shame I saw that we were taking all their poor breakfast—nine cobs of boiled maize. They thrust them into my hand and urged me back up the hillside with many expressions of alarm as they pointed to the valley.

“God bless you,” I said in English, and left them, Duncan met me as I reached the cover on the hill.

At this point in our journey, I made a major error for which I can never forgive myself. As the soldier in the party, I should have known better than to have agreed to stay near one of the disused earth platforms on the hillside so that Duncan, who was chilled by the wind, could obtain shelter. Crouching against the hillside we ate our boiled com—still warm—and enjoyed it thoroughly. At least this would not pass straight through our systems. I was about to say to Duncan, “We really must go after you’ve eaten that corn cob,” when the sound of voices reached us. Within a few seconds five Chinese came through the trees from the direction of the village, searching for wood. They were unarmed, but two of them had long, thick sticks.

We had not time to hide properly—we were actually moving towards some bushes below a rock-face when they appeared.

“Lie still and they won’t see us,” I whispered to Duncan. The soldiers had certainly not seen us; they were fooling about, throwing stones at one another as they came towards us. Each minute seemed an hour as they picked up sticks or tore at branches hanging from the trees. I dared not turn my head to look at the three to my right from whom I expected at every moment to hear the shout which would herald discovery. The other two were now about twenty feet away, their backs to me as they ht cigarettes. I heard a whisper from Duncan, who lay six or eight feet to my left.

“What is it?”

“They’ll spot us for sure. I’m going to make a break for it.”

“Don’t be an idiot,” I said. “Keep still and they’ll never see you. They aren’t looking for us.”

“I’m not going to take a chance,” he said. “You stay if you want to. As I’m going, I’ll try to lead them away from you.”

He rose instantly to his feet and dashed away towards the corner of the platform we had just left; the sound of his feet on the leaves and dead branches seemed to crash upon my ears. The two men to my front whirled round, gave a mighty shout, and set up an excited chatter on seeing him; the other three came running across to join them. All five stood there, shouting and pointing. Duncan might have made good his escape, so long were they in recovering from their surprise, but he tripped over a root and fell. At that they gave chase and were closing on him as he disappeared round the shoulder of the hill.

If Duncan had done nothing else, he had kept his promise to lead them away from me. I did not intend to waste this opportunity now. Looking quickly about me, I made for the thick cover higher up the hillside, from whence I could observe the course of events.

They brought Duncan back about ten minutes later. It was his fair beard I saw first as he came through the trees with four of the soldiers. The fifth had preceded them by several minutes to report the news of his capture to the village. As the main party arrived in the village street, I saw the entire garrison crowding the road to look at him, before he was taken into a large house which I guessed to be the local headquarters. A few moments after he had disappeared into the courtyard I remembered that all Duncan’s clothes were still on the hill-top.