Punch, ‘Rint’ and ‘Repale’ — 1843

In his study of Punch Richard D. Altick suggests that the paper, founded in July of 1841, ‘served as a weekly illustrated comic supplement to The Times’ That paper, along with the other dailies, established the ‘news’ from which Punch chose the subjects for its satires (1997, xix, 68). Although dependent upon the dailies, Punch, as a weekly, was able to scoop the monthly journals (Price, 30). Moreover, unlike the newspapers, Punch, through its cartoons, was able to add a visual dimension to its satiric commentary. Not surprisingly, during the ‘Year of Repeal,’ Daniel O’Connell and his movement were frequent targets for Mr. Punch. Although much less conservative than The Times, Punch was just as vehemently opposed to O’Connell and all his works.

Although Punch was the first publication to label its political drawings ‘cartoons,’ the paper did not invent the genre (Houfe, 21). It did, however, take the wild, often crude and semi-pornographic visual comic productions of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and helped to make them acceptable for middle-class tastes. Boasting of the quality of its political cartoons, one of the paper’s writers, William Makepeace Thackeray, claimed: ‘we have washed, combed, clothed, and taught the rogue good manners.’1

Mr. Punch did not make cartooning respectable all by himself. In the decades immediately preceding the founding of the magazine, a few caricaturists and cartoonists, such as John Doyle (who signed his works ‘HB’), produced drawings that were less grotesque and abrasive but often more politically astute than what generally appeared in most ‘caricature magazines.’ Although not opposed to occasionally putting their heads on the bodies of animals, Doyle did not caricature his subjects. They usually appeared as normal human beings, although not always in normal situations.2 Punch built upon John Doyle’s approach to political cartoons, making them the dominant feature of each issue. The magazine’s editor, Mark Lemon, and a roundtable of cartoonists, such as Doyle’s son, Richard, John Leech, J. Kenny Meadows, H. G. Hine, and writers, such as Douglas Jerrold and William Makepeace Thackeray, set the topics for the weekly ‘big cuts’ or full-page political cartoon. These ‘big cuts’ were the visual equivalent of the lead articles in The Times.3 The topic was usually political, and the subject in the 1840s was often Daniel O’Connell.

As they developed their depictions of the Irish leader, Punch cartoonists were not working in a vacuum. Images of O’Connell, portraits as well as caricatures, were widely known. O’Connell himself commissioned his first portrait as a political leader from John Gubbins in 1818. In fact, throughout his career, O’Connell paid great attention to his public image. During the struggle for Catholic Emancipation, he often appeared in the uniform he had designed for the Catholic Association (O’Ferrall, 92-94, 95-96, 100). Green was a predominant color in O’Connell’s carefully chosen wardrobe, which even today would grace a St. Patrick’s Day parade. As his political career developed, O’Connell learned to carefully stage-manage his public appearances. Gary Owens points out that, ‘Such visual displays were essential to the mass public support that grew up around him from the early 1820s onward — and they were deliberately constructed’ (104). O’Connell’s image was everywhere in Ireland, appearing in media as varied as print, textiles and Staffordshire pottery. Owens states that O’Connell was the first political figure in the United Kingdom, apart from members of the Royal Family, to have been commemorated on a large scale in pottery (126).

In England, however, O’Connell’s image may have been better known through cartoons. From the time he entered the political arena, O’Connell was the subject of many cartoonists who distorted his image and often reduced him to a comic level. Yet, not all of the earlier cartoons, however antagonistic, were ridiculous caricatures. A fairly recognizable drawing of O’Connell appears in ‘THE HUMBLE CANDIDATE,’ an 1818 cartoon published by Thomas MacLean of London (O’Ferrall, 96). O’Connell kneels before a Roman Catholic bishop, an act that may have suggested to Protestant viewers that he was in thrall to foreign powers (ie. the Papacy or, possibly, France). Although O’Connell’s appearance is normal, the bishop’s caricature already shows the long upper lip and prognathous jaw that eventually would become characteristic of English anti-Irish cartoons (Curtis, Jr., xix-xxii, 89-93). Behind O’Connell the cartoonist has depicted a woman prostrating herself in the presence of the bishop. Such an image could have suggested to Protestant readers an abrogation of independence and self respect and perhaps the worship of false idols.

John Doyle, a quarter of whose illustrations between 1829 and 1847 featured O’Connell, had a particularly sharp eye for political tensions and dynamics (O’Ferrall, 92). Many of Doyle’s cartoons dealing with O’Connell emphasized the Liberator’s supposed influence over the Whigs. For example, in the 19 January 1835 issue of HB’s Political Sketches, O’Connell is seen as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The Irishman tries to persuade two sheep, Whig leaders Melbourne and Russell, to ‘merge all over trifling differences and make common war on these tyrannical watch dogs,’ referring to the Tories, Wellington and Peel, who, in canine form, are standing by watchfully with ears erect (McCord, figure 9). In another drawing Doyle depicts O’Connell, armed with a shillelagh, leading a chain gang of Whig politicians.4 Even in these cartoons, O’Connell is normal-looking, even handsome, albeit in a cheerful and chubby sort of way.

Not only did Doyle establish O’Connell as a central figure in political cartoons, but, as James N. McCord points out, by the 1830s he had created a stereotype of the Liberator. ‘Through the clever and imaginative use of symbols, metaphors, and personifications, HB turned the Irish hero into a powerful, but cunning and deceptive creature whose methods gave him the upper hand of the English politicians, especially the Whigs’ (61). Doyle greatly exaggerated O’Connell’s influence over the Whigs. He liked to make reference to the MPs O’Connell controlled as the ‘O’Connellite tale’ that maintained the Whigs in power. At one point he drew the Liberator as a large rat-tailed marsupial with the Whig leaders in his pocket (McCord, figure 5). Although Doyle had once admired O’Connell for his efforts for Catholic Emancipation, the Liberator’s nationalism and especially his tactics offended the cartoonist’s essential conservatism. Picking up on O’Connell’s remark that those Irish who opposed Repeal should have the scull and cross bones marked on their doors, HB frequently used this device in his cartoons, including those attacking the Liberator’s ‘rent.’ Yet, as McCord suggests, Doyle depicted O’Connell as a political opponent and ‘not as some monster outside the world of English gentlemen.’5

While continuing the focus on O’Connell’s role in Anglo-Irish politics, Punch went farther, and turned him into a moral monster. O’Connell’s fund-raising tactics struck Punch’s staff as hypocritical and were, therefore, frequent targets. The magazine’s first cartoon to feature the Liberator appeared in January 1842. In ‘A DANIEL, – A DANIEL COME TO JUDGMENT!’ O’Connell is drawn as a broad-shouldered, curly-haired, somewhat jowly man clad in his robes of state, wearing the chain of office as Lord Mayor of Dublin. Seated at a table, accepting ‘rint’ in a receptacle strongly resembling a church collection box, O’Connell passes judgment on a small, ragged, unshaven peasant before him. The man has failed to pay his contribution to the Repeal Association, and pleads, ‘It’s yer honour’s example I thought I was following in regard o’ the Rint.’ O’Connell replies in the same stage-Irish brogue, ‘Get out wid ye that’s another thing quite entirely. I commit ye as a rogue and a vagabond’ (ii., 17).6

In focusing on O’Connell’s use of the Repeal Rent to fund himself and his campaigns, Punch, like The Times, exhibited an imperial tendency to dismiss or mock any native practice outside of metropolitan experience. These journals depicted the Repeal Rent as only a money-making scheme for O’Connell’s private benefit rather than a participatory, stake-holding grass-roots effort to effect political change.

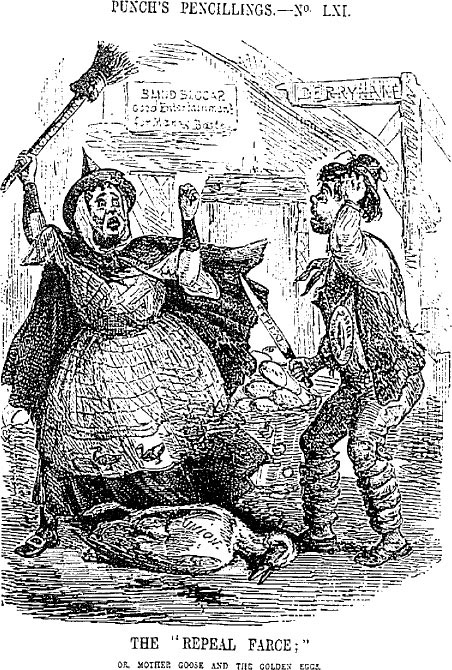

Early in 1843, Punch published a cartoon by J. Kenny Meadows, presenting ‘THE “REPEAL FARCE;” OR, MOTHER GOOSE AND THE GOLDEN EGGS’ (Figure 2.1). O’Connell, dressed as a stout, curly-haired pantomime dame, is seen furiously waving a broomstick labeled ‘Agitation’ at a puzzled and apparently blind peasant, who in his confusion, has killed the ‘Union’ goose with his ‘Repeal’ knife.7 The peasant wears a medallion labeled ‘Repeal Association.’ Behind Mother Goose/O’Connell is a large basket of ‘Rint’ eggs. The cartoon implies that O’Connell, in spite of his rhetoric, had a monetary interest in keeping the Union alive so that his ‘agitation’ would continue to collect his income.

Accent and dialect throughout the United Kingdom were (and are) signifiers of class and ethnicity, usually implying either superiority or inferiority. Thus, Punch’s use of ‘rint’ for ‘rent’ to indicate an Irish dialect had both literary and political implications. As Seamus Deane points out, numerous nineteenth-century writers, including Maria Edgeworth and Gerald Griffin, used dialect to lend authenticity and realism to their Irish peasant characters. Dialect, however, also indicated inferior character and was ‘indissolubly allied with degradation.’ Deane suggests that in many literary works ‘deformity of speech indicates moral, social or political delinquency’ (59, 63). The editors of Punch would have declared O’Connell delinquent in all three areas.

Figure 2.1: Punch, iv. (1843), 37.

By labeling the money raised for Repeal as ‘rint,’ Punch made fun of O’Connell’s source of funds, while simultaneously placing his methods morally outside the ‘normal’ bounds of political financing. Most parliamentary candidates had private means or received their financial backing from local landlords and aristocrats. Although English reform associations had adopted O’Connell’s use of broad-based funding, the idea of using contributions to support a popular political leader was still a relatively new concept. The fact that the Liberator drew upon the contributions of a poverty-stricken (and in British eyes an often unruly) peasantry made his system seem despicable.

Punch’s cartoonists had a variety of methods for satirizing their victims. In the cartoon ‘REPEAL FARCE’ Meadows costumed O’Connell as Mother Goose, a standard transvestite role in pantomime performances.8 Although the gender inversion of this role was traditional, placing O’Connell in skirts suggested multiple meanings. He could be seen as a deceiver or a trickster, someone of whom the viewer should be suspicious. The image also implied that O’Connell, like a character in a comic show or a fairytale, should not be taken seriously. Casting O’Connell as Mother Goose also echoed the use of ‘goose’ as one who was silly or foolish. Finally, while cross-dressing was part of the comedy of the pantomime dame, any feminization of the Irish leader was an implied insult, an attack on his manhood and his status.

Through repetition Punch was able to build upon certain words and images. In the title of H. G. Hine’s cartoon, ‘GENUINE AGITATION, (A Scene from Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR)’ (Figure 2.2), ‘agitation’ acts as a code word widely used to refer to O’Connell’s Repeal movement, while at the same time suggesting the fear that Daniel O’Connell should feel when threatened by English power. The theatrical setting is both classical and Shakespearean. Hine draws O’Connell as Brutus haunted by the Duke of Wellington, who is cast as the ghost of Julius Caesar. The military might of Britain and its capacity for control are represented in Wellington’s helmeted, spectral figure. O’Connell, cast as the assassin, is clad in a short-skirted Roman tunic.9

Figure 2.2: Punch, iv. (1843), 217.

In the cartoon Caesar/Wellington brandishes a rolled bill labeled ‘Debate, May 9th.’ This is a reference to the Duke’s response to a question raised in the House of Lords that day by the Earl of Roden (an Irish peer with strong Protestant sympathies), concerning the ‘awful subject of the repeal of the union’ and the excitement it was causing in Ireland. Roden, as reported in Hansard’s, complained:

The great cause of this excitement was the assembling together in different parts of the country of immense masses of the people, and those assemblies being addressed by demagogues, and he [Rodin] regretted to say, addressed by Romish priests in language the most seditious and the most violent — language which, he must say, tended to inflame the minds of the people, concerning England, and towards the connection with his country [Ireland] (Hansard’s, 69:4-5).

After assuring their lordships of the basic loyalty of the Irish people, especially of those in Protestant Ulster, ‘with whom he was more immediately, connected,’ Roden asked the Government what it was prepared to do about the situation.

In response Wellington rose to assure their lordships that her Majesty’s Government

had adopted measures in order to enable the Irish Government with certainty to preserve the peace in Ireland, should any attempt be made to disturb it…. There could be no doubt of the intention of her Majesty’s Government to maintain the union inviolate and [if necessary] to come down to Parliament and call on Parliament to give her Majesty’s Government its support in carrying into execution any measures which may be considered necessary to maintain the union inviolate (Hansard’s, 69:7; italics added).

The words ‘certain,’ ‘no doubt,’ and ‘any measures’ emphasized the Government’s intention to meet any threat to imperial order or to the Union. As Peel made a similarly strong statement in the Commons on the same day, it seems clear that the Government was sending a warning to O’Connell, while reassuring its supporters of its readiness to deal with any emergency (Nowlan, 1965, 45).

Punch’s cartoon was a comic reinforcement of the Government’s message. Although the magazine was not Tory in its views, it was very consciously a part of the political and economic establishment of Britain. Given that most of its readers were English, its cartoons on O’Connell are good examples of Roger Fowler’s contention that the press may reinforce a consensus that links readers to authority, while simultaneously identifying ideas and groups that are beyond acceptance (48-54). Hine’s Brutus/O’Connell is clearly an enemy of the British consensus supporting the preservation of the Union. He is so disturbed at the sight of the Iron Duke (and the reminder of that formidable speech) that his hair stands on end. His sword of ‘Agitation’ has fallen to the floor, and in his fright, he kicks over the table on which he was writing ‘Repeal’ by the lamp of ‘Revolution.’ (This representation of O’Connell as cowardly may reflect the lingering memories of his failure to appear for the duel with Robert Peel in 1815.)

Figure 2.3: Punch, v. (1843), 5.

In July 1843 John Leech drew O’Connell, once again in a dress, although this time the costume could be justified by the incident on which the illustration was based. The cartoon, ‘REBECCA AND HER DAUGHTERS’ (Figure 2.3), referred to recent disturbances in Wales, where ‘Rebeccas,’ men disguised in women’s clothing, tore down toll gates in a series of violent incidents. A force of 1,800 English soldiers was stationed in western Wales that summer to prevent further destruction.10

Creating an image at once feminizing and deceptive, Leech shows O’Connell wearing a bonnet and a long-skirted dress over his trousers. The purse at his waist is, of course, marked ‘rint.’ He leads a wild mob of Repealers, all in women’s clothing, past gateposts adorned with the faces of the Duke of Wellington and Peel. Peel himself, as the gatekeeper in a night-cap, peers out of a door over which there is a sign bearing his name. One ‘daughter,’ representing perhaps William Smith O’Brien, saws at the ‘Union’ plank in the gate, while others attack planks labeled ‘poor laws,’ ‘tithes’ and ‘church rate.’ (The gable end of Peel’s building is topped by a cross, perhaps suggesting the established church.)

Punch’s message was apparently that the Irish Repealers would be no more successful in their resistance to English domination than were the Welsh Rebeccas. Editor Mark Lemon and cartoonist John Leech ignored, of course, the remarkable difference of scale between the localized Welsh incidents and the national mass movement that Repeal represented in Ireland. Punch’s consistent refusal to acknowledge the breadth and depth of the Repeal movement was yet another method of negating O’Connell and his huge number of followers. At the end of the summer, Punch further ridiculed the Repeal movement in an article calling for ‘the repeal of the parochial union between Brompton and Kensington’ (v., 1843, 64). Here the weekly appropriated Ireland’s national cause and re-scaled it to the ridiculously low level of London parish-pump politics.

References to fairy-tales and classical themes were frequent in Punch, as reflected in a pair of illustrations from 8 July 1843. The first is ‘THE IRISH OGRE FATTENING ON THE FINEST PISANTRY’ (Figure 2.4).11 A very fat Daniel O’Connell, dressed in a classical skirted tunic, is shown with two of the usual attributes of Hercules: he holds a rough club, labeled ‘Repeal,’ and wears a lion’s skin on his head, a reference to the lion killed by Hercules. O’Connell’s headdress, however, is a comical representation of the British lion. On top of the lion’s head sits a ‘caubeen,’ the stereotypical Irish peasant’s hat, with a ‘dudeen’ or clay pipe protruding from the hat band. Yet, the O’Connell figure looks more like a Hibernicized fairy-tale ogre than a classical hero. He sits upon huge sacks of ‘rint’ and ladles out a bowl of ‘Agitation Soup’ for himself. The ‘soup,’ as it spills into the giant’s dish, consists of small human figures representing the Irish peasantry. O’Connell is cast as a cannibal devouring his own people.

Figure 2.4: Punch, v. (1843), 15.

In dialect spelling, the cartoon’s title is a play on O’Connell’s famous description of his followers as ‘the finest peasantry in the world’ (the phrase can be seen in the steam rising from the soup). However, while ‘pisantry’ represented the stage-Irish dialect for ‘peasantry,’ it also echoed a dismissible phrase in French (‘pisant’). The cartoonist was both mocking O’Connell’s supposed accent and disparaging his fellow countrymen. As Seamus Deane points out,

Irish speech is a political territory, exotic and barbarous, at times indecipherable…. Abnormality characterizes both the speaker of Irish English and the speaker of the Irish language itself…. The speakers of these languages can [in fiction] be endearing, sentimental, loyal, savage, humorous, excessive – but they are never subject to the charge of being cool and analytic. Such a role is preserved for those whose language is the King’s or Queen’s English (Deane, 65; italics original).

Whenever they used dialect words such as ‘rint’ or ‘Repale,’ Punch’s cartoonists and writers postulated a normative, metropolitan superiority. In linguistic terms, the dialect words ‘cued’ difference (Fowler, 60-61). Punch’s use of dialect signified not only ‘Irish’ but also ‘inferiority.’ At the same time, it served to reinforce a common sense of Britishness among the journal’s readers.12

In the same July issue that featured O’Connell as an ogre, language may also have inspired a second drawing, which, with its accompanying text, does refer to Hercules. Not a ‘big cut,’ this smaller illustration was part of a satire titled, ‘Punch’s Labours of Hercules. Labour the Seventh. — How Hercules Caught and Tamed a Prodigious Wild Bull Which Ravaged a Certain Island’ (v., 1843, 18). Hercules leads a bull by a banner bearing the words ‘Justice for Ireland,’ the phrase being O’Connell’s rallying cry from a speech given in Commons on 4 February 1836. Punch cartoonists enjoyed throwing it back at him. In fact, the bull’s head is a caricature of Daniel O’Connell. This may be a visual pun on the alleged Irish misuse of language – the famous ‘Irish bull.’ Hercules, identified by his huge club and a lion skin, is presented as a demigod who can solve the problem presented by the Hibernian bull.

Punch describes the bull/O’Connell as voraciously hungry:

He consumed a wonderful amount of provender annually in the shape of a material which in the language of the country was called Rhint. This provender he obtained by dint of his roaring, which was rather musical to the ears of the majority of the Hibernians, who, to tell the truth, were of an obstreperous disposition…hoping that it would terrify the adjoining country into conceding to them certain rights and privileges, it had unjustly withheld from them (18).

O’Connell was here reduced to an animal. His Repeal movement was simply a kind of noise intended only to frighten the British. The stereotype of violent Irish behavior was echoed in the phrase ‘obstreperous disposition.’ All of this was Punch’s way of saying that the Repeal movement did not represent legitimate Irish interests. The paper did admit, however, that the bull’s roar was not quite without reason. Within the limits of its satire, Punch acknowledged that Ireland’s poverty was a source for discontent. Although they could ill afford it, the Irish kept their ‘bull’ copiously supplied with

Rhint, to encourage him to bellow and roar…. There was, as a matter of fact, no little reason in his roar; at least on the part of those who upheld him therein. For they, for the most part, had been reduced to live on potatoes and salt…. And he put it to John Bull, who was extremely sensitive in his own case to the wrongs of the stomach… whether starvation was not a fair excuse for roaring (18).

The author of the satire seems to assume as common knowledge that hunger already existed for that part of the Irish population entirely dependent upon potatoes for survival. Seasonal and regional shortages periodically occurred in pre-famine Ireland.

Punch continued to use food metaphors as a basis for its ironic allegory. Excessive dependence on the potato meant that ‘Irish men were reduced to fare like Irish pigs!’ Hercules, however, felt that ‘what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.’ The satire then shifted its focus, discussing, in a culinary way, the Irish preference for ‘mutton’ (Catholicism) rather than ‘beef’ (Church of England) or even ‘veal’ (Scottish Presbyterianism). Hercules understood the Hibernians’ call for ‘Liberty for Mutton’ and ‘No Beef.’ Those who summoned Hercules’ aid (presumably the British Parliament), at first refused to see any injustice in having the Hibernians pay a tax for ‘beef’ they did not want (tithes to the Church of England). Finally Hercules ‘drubbed’ some ‘common sense and rationality into the assembly,’ and ‘the privilege of mutton was conceded to the Hibernians and beef was left to their option.’ As a result the bull was tamed and presented to Her Majesty the Queen (v., 1843, 19).

This rather laboured satire implied that some religious reform was due Ireland (although Punch would be appalled a year later to see how far Peel was prepared to accommodate Irish Catholics). This was an instance where the paper’s anti-Catholic bias was tempered by its occasional radical bent. Yet, the deeper economic questions that the article touched upon were not explored. Having recognized hunger as a problem, Punch preferred to focus on religious reform, disregarding any need for dealing with underlying questions of land ownership, tenant rights, or commercial trade, much less nationalism.

O’Connell and Repeal continued to be the mainstays of Punch’s commentary on Ireland. A few weeks later the magazine published one of its cleverest O’Connell cartoons, ‘THE SHADOW DANCE. (From the ballet of “Ondine” a little altered)’ (Figure 2.5). O’Connell appears again as a skirted figure, this time as a ballerina dancing with his own shadow cast by a moon bearing the face of Sir Robert Peel. The depiction of the Irish leader in a feminine role drawn from high culture may have been a suggestion that the politician did not represent the true, native Irishman. There is certainly a contrast between the ‘ballerina’ and the group of wild Paddies seen jigging and waving their shillelaghs in the background before a castle labeled ‘Blarney,’ a word that defined the English view of the reliability of Irish discourse.

The ballet ‘Ondine’ was one of the current successes of the London season, having premiered there on 22 June 1843. One of the highlights of the production was the pas de l’ombre in which the water nymph, Ondine, having assumed mortal shape, became fascinated with her own shadow. In Punch’s cartoon, O’Connell, as Ondine, is drawn in almost the exact pose seen in a poster of Fanny Cerrito, who premiered the role in London (Bremser 2:1047-48). The main difference is that while the dancer is posed en point with her right hand over her head to balance herself while her left gestures towards her shadow, O’Connell reaches madly for his shadow with both hands, threatening to throw himself off balance. The uncooperative shadow, labeled ‘Repeal,’ thumbs its nose at the over-eager Liberator. O’Connell is depicted as a victim of his own delusions.

Figure 2.5: Punch, v. (1843), 69.

The same rude nose-thumbing gesture is seen a few weeks later in the cartoon ‘RECESS RECREATIONS,’ in which Sir Robert Peel and the Duke of Wellington are shown as hunters ‘TRYING TO BAG THE IRISH WILD GOOSE.’ The ‘goose’ is a winged O’Connell, who flies by, thumbing his nose at them (v., 1843, 109). Lord Brougham in a top hat appears as a gillie or perhaps as a liveried rat-catcher with three rats hanging from his shoulder and a pouch for more vermin ready at his hip. Beneath the air-borne O’Connell, Ireland, with the flag of ‘Repeal’ flying over it, is in flames. The goose reference may be to the Wild Geese who fled Ireland after the Treaty of Limerick in 1691. The immediate context for the cartoon, however, was probably the Irish party’s ability to delay and ultimately water down the provisions of the Government’s Coercion Bill.13

By the summer of 1843 the Government began to fear that O’Connell’s ‘monster,’ yet peaceful, meetings of tens of thousands of supporters would turn violent, threatening the Imperial administration in Ireland. O’Connell’s speeches were carefully monitored, and O’Connell knew that he was walking a fine line between change and revolution. He regularly distributed copies of his speeches at his meetings to all the reporters and government representatives present. On 20 August, however, O’Connell, speaking extemporaneously, made a critical reference to the Queen’s speech given at the closing of Parliament. Government agents in the audience overheard the slip. O’Connell’s remarks provided the basis for charges of sedition later filed against him.

As tensions between the Government and the Repeal movement mounted, O’Connell scheduled a mass meeting for 8 October at Clontarf, just north of Dublin. This was the highly symbolic site of Brian Boru’s victory over the Danes in 1014. Unbeknown to O’Connell, the city’s Repeal Association called for ‘Repeal cavalry’ to attend the procession to Clontarf. O’Connell quickly retracted the provocative statement, but the Government had already decided to act (MacDonagh, 1989, 239). At the last minute it banned the meeting on the grounds that the organizers intended to bring about alterations in the law through intimidation and physical force. The city was filled with troops, and there was a real possibility of bloodshed if the Repealers had tried to assemble. O’Connell’s bluff had been finally called, and he canceled the meeting.

Not satisfied with this victory, the Government arrested Daniel O’Connell, his son John, Charles Gavan Duffy (the owner and one of the editors of The Nation), the editors of two nationalist papers, the Pilot and the Freeman’s Journal, and two Roman Catholic priests on 11 October 1843. Charges included an unlawful attempt to alter the country’s constitution and government, and an effort to cause unrest in the army (Broderick, 155).

Figure 2.6: Punch, v. (1843), 199.

The 4 November issue of Punch carried J. Kenny Meadows’ cartoon, ‘THE IRISH FRANKENSTEIN’ (Figure 2.6). O’Connell, in a dramatically billowing caped coat, conjures up the Repeal monster, a visual reference perhaps to The Times’ phrase ‘monster meetings.’14 While Meadows’ cartoon refers to Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel, it also incorporates the visual stereotype of the Irish peasant that had been evolving in Punch over the past several years: the monster is long-lipped, curly haired, clad in a ragged coat with a clay pipe clenched in his teeth. Waving his club, the monster, with his huge fists and massive shoulders, embodies violence. The addition of horns makes it more devilish than Shelley’s creation. At the same time, the monster also recalls countless drawings of ‘Paddy,’ dancing his jig with his shillelagh raised in one hand. The grotesque figure is labeled ‘Repale,’ signifying the comical and uncouth Irish dialect. However, this may also be a play on words, ‘Pale’ recalling the line of fortifications that had once separated the English from the ‘wild Irish’. To Punch the obstreperous Irish were still ‘beyond the Pale.’

O’Connell, cast in the role of Baron Frankenstein, is portrayed as deliberately manipulative. He extends his long fingers in a magician’s or mesmerizer’s dramatic gesture. Yet the size of the gigantic, demonic figure and its fierce movements seem to endanger even its creator. Thus, as the monster waves its shillelagh, the immediate threat seems to be to O’Connell himself.15 Is the monster dancing to O’Connell’s instructions, or is it about to attack the man who invented it? Punch seems to be asking, who is in control of whom? This is one of the last Punch cartoons to suggest that O’Connell actually had any power. Later cartoons usually depicted him as a cadger or beggar, looking for money and deceiving his followers.

Responding to L. Perry Curtis, Jr.’s argument that Punch’s cartoon images of the Irish were uniformly hostile and racist, Ray F. Foster suggests that Punch ‘could be resolutely pro-Irish in its early years,’ and that it was the emergence of the extreme nationalism of Young Ireland, as well as the growing presence of poverty-stricken Irish immigrants in Britain, that pushed the magazine towards more anti-Irish sentiments and images. He also argues that it was not until after the Famine that the undeniably simian face of the Irish ape man appeared in Punch’s pages (R. F. Foster, 174).

If we look, however, at Punch’s cartoons from 1842 to 1843, there is a great difference between the representations of O’Connell and the depictions of his Irish peasant followers. While the Irish leader was often cast and clad in absurd ways, the Punch cartoonists had not yet distorted his features. O’Connell’s face was only mildly caricatured and remains easily identifiable with his portraits. In contrast, the faces of the Irish peasants who appears in ‘A DANIEL, — A DANIEL COME TO JUDGMENT!’ and in ‘THE “REPEAL FARCE,”’ already suggest the pug nose with the collapsed bridge and the long upper lip, which, according to Curtis, the Victorians associated with degeneracy (123-26). The ‘Repale’ monster in ‘THE IRISH FRANKENSTEIN’ was already evolving into the simian-faced Paddy who would represent Punch’s depiction of Fenians in the 1860s.16 All of this is in sharp contrast to John Doyle’s cartoons about O’Connell and his Irish supporters. In Doyle’s ‘A SIMPLE QUESTION Asked in “Sober Sadness,“’ an Irish peasant politely inquires of O’Connell when he can expect Repeal. O’Connell, sitting at a table with two colleagues working on a series of reform issues, is too busy to get ‘Repeal’ down from the shelf in the background. The features of neither the Liberator nor the peasant are caricatured. As James N. McCord points out, Doyle’s cartoons were virtually free of racism.17

In one sense Punch’s cartoons of O’Connell were no worse or more unfair than those of all the other Parliamentary politicians the magazine satirized. They all appeared in absurd settings as school boys, as pantomime figures, and as ballerinas in tutus. Suggesting inappropriate appearance, behavior or displacement is a standard comic device. It was part of the essentially healthy-minded satiric skepticism with which Punch regarded men who were inclined to take themselves very seriously. Moreover, Punch generally observed limits to its satiric assaults. Altick emphasizes what he calls Punch’s ‘tolerant assumption’ of the basic honesty of its numerous parliamentary victims (1997, 127). In the case of O’Connell, however, Punch’s most damaging attacks were directed at his honesty.

Altick argues that the magazine was ‘a comic paper with a social conscience,’ pulled in its early days between ‘radicalism and gentility’ (1997, xix, 186-87). Lemon, Douglas Jerrold and Thackeray hated what they regarded as hypocrisy and dishonesty, especially when the lower classes were the victims. To them O’Connell’s ‘rint’ seemed like an unconscionable scheme to rob people who were already paupers. In constantly calling attention to O’Connell’s fund-raising tactics, however, while never questioning the English manner of supporting its politicians, the paper assaulted O’Connell’s character. Few politicians of the period were subject to this type of highly personal attack.

Up to a point, of course, the paper’s attitude towards O’Connell can be understood in terms of the political and social values of its editors, writers and cartoonists. O’Connell, who was no stranger to demagoguery, was often a fair target for Punch’s satire. J. J. Lee has pointed out that ‘The always emphatic, and often vituperative, vocabulary in which he [O’Connell] expressed his views forced his listeners and readers to take sides. No one could be neutral on O’Connell’ (5). O’Connell was certainly a political force with which to be reckoned. Moreover, since Punch was nothing if not patriotic, its opposition to any rupture in the Union is not difficult to understand. Therefore, given the nature of the publication and its editorial policies, O’Connell and Repeal were natural and legitimate targets for the magazine’s satire.

The problem does not lie so much in the way that Punch dealt with O’Connell as with the fact that the Irishman was unlike any other public figures the magazine satirized. O’Connell was not only a politician, the leader of an important parliamentary faction and the spokesman for certain controversial ideas. He was in a very real sense The Irishman in Parliament. He had made himself and was accepted as the spokesman for the majority of Irish people and a symbol of what he and they called ‘the Irish nation.’ No one else in Parliament occupied a similar position. In 1845 Punch acknowledged the opening of the new session of Parliament with ‘Black Monday, or, the Opening of St. Stephen’s Academy’ (viii., 71). All the leading politicians are caricatured as school boys returning to their classes. In the throng, quite recognizable in his Repeal Cap and glum jowliness, is O’Connell, the only one among them who represents a national group.

When Punch lampooned Peel, it may have questioned the Tory leader’s policies and his judgment, but not his status as an Englishman. Turning O’Connell into a wild goose to be hunted, into a tunic-clad Shakespearean villain, into a Welsh ‘Rebecca’ in a dress, or into an ogre devouring his own people, Punch reinforced the sense that the Irishman was beyond the English Pale. He was outside of the legitimate circle of British politics and politicians. Worse, given O’Connell’s position as the Irish leader, there was a danger that denigration and ridicule of O’Connell and the Repeal movement would all too easily turn into denigration and ridicule of Ireland and the Irish.

R. F. Foster suggests that the Liberator’s ‘theatrical, self-parodying, larger-than-life elements were much appreciated’ by Punch’s staff, tempting the magazine in its more generous moments to treat O’Connell as ‘a sort of Irish Mr. Punch’ (174). And that was the problem. No politician was ever considered a stand-in for the paper’s comic symbol of England. Yet, it was assumed that O’Connell could be treated as a Hibernian Mr. Punch.

Consider the letter that Mr. Punch addressed to O’Connell when the latter was imprisoned in Dublin in 1844. The letter was, of course, written anonymously by Thackeray, who probably had as much experience with Ireland as anyone else on Punch’s staff. Married (not happily) to an Irish woman, he had many contacts in the other island. His Irish Sketchbook, published in the ‘Repeal Year’ of 1843, was one of the most successful travel works about Ireland. Thackeray undoubtedly had a certain amount of sympathy for the country and its people. When Daniel O’Connell was tried and imprisoned in 1844, Thackeray, writing as Mr. Punch, published a ‘letter’ to the Liberator. Mr. Punch/Thackeray expressed some regret that this old, favorite target of his satire had been brought so low. Of course, the charges against him were justified. Addressing O’Connell, Thackeray wrote:

If you did not organize conspiracy, and mediate a separation of this fair empire — if you did not create rage and hatred in the bosoms of your countrymen against us English — if you did not do, in a word, all that the Jury found you guilty of doing — I am a Dutchman!

But if ever a man had an excuse for saying hard things, you had it: if ever a people had a cause to be angry, it is yours: if ever the winning party could afford to be generous, I think we might now….

Thackeray made a good point in arguing that there would be no benefit for either England or the Government to keep O’Connell in prison. ‘Though we may lock you up; yet for the life of me I don’t see what good we can get out of you.’ However, his next comments revealed the somewhat exotic place Thackeray thought O’Connell occupied in English imaginations.

As I said to Mrs. Punch yesterday, ‘If any friend from Ceylon were to make me a present of an elephant — what should I do with it? If a fine Bengal tiger were locked up in my back-parlour — what would be my wish? Out of sheer benevolence I should desire to see the royal animal in the Strand.’

Broad-mindedly, Thackeray wanted no ‘vulgar triumph’ over O’Connell’s situation. That would be the work of ‘low-minded knaves. If ever I laugh, it shan’t be because a great man falls. I wish you would come out of prison, for how can I poke fun at you through the bars?’

Thackeray’s Mr. Punch then scolded O’Connell for his lies about the English and for his bragging and swaggering. Then, he fanaticized the ideal solution. The Queen would visit Ireland, drive to Richmond Prison on the Circular Road in Dublin and free the Liberator, saying

‘Let bygones be bygones…a fib or two more or less about the Saxons won’t do us any harm: but try now, jewel, and be aisy: don’t talk too much about killing and eating us: don’t lead poor hungry fellows on to fancy they can do it…have no more of that talk about bullying JOHN BULL. Keep the boys quiet, and tell them they can’t do it. It’s no use trying: we won’t be beaten by the likes of you.

‘But we have done you wrong, and we want to see you righted; and as sure as Justice lives, righted you shall be.’

Thackeray’s Mr. Punch concludes by saying, ‘Such are the words that I wish to whisper to you in your captivity, — of reproof, and yet of consolation; of hope, and wisdom and truth!’18

The letter is Thackeray and Punch at their best; it is magnanimous to a fallen enemy, who is accorded some dignity, if only as a sort of exotic species. Ireland’s woes are acknowledged, if not identified, and justice is vaguely promised. Thackeray’s sympathy for O’Connell, while certainly limited, was no doubt genuine, as was his concern for Ireland. However, as Roger Fowler suggests, when analyzing a discourse, we should always try to identify its actual ‘participants: the source, the addressee, and the referent(s)’ (210). In this case, the ‘source’ is not Thackeray. Like all of his contributions to the magazine, his piece was anonymous. He spoke for Punch, and Punch spoke with the moral authority of British respectability, without which its satire would not work. The ‘addressee’ is certainly not O’Connell, but rather the paper’s British readers, who represented the established, respectable, and informed opinion Punch had to cultivate in order to thrive. In identifying the ‘referent’ we should follow Fowler’s suggestion that, ‘the ostensible subject of representation in discourse is not what it is “really about:” in semiotic terms, the signified is in turn the signifier of another, implicit but culturally recognizable meaning’ (170). The subject of Thackeray’s piece was neither O’Connell nor Ireland, but England. Reminded once again of Ireland’s shortcomings and offensives, readers would have learned nothing about either O’Connell or his country. What Thackeray clearly and confidently laid out, however, was England’s sense of magnanimity, justice, propriety, and understanding, all symbolized by that fantasy of the Queen’s visit to O’Connell. As we will see throughout this study, much of discourse about Ireland was really about the British reaffirming their superiority, their wisdom and, of course, their monopoly on ‘truth.’

Notes

1. See Altick, 1997, 122. As Price points out, Thackeray was also a visual artist. He did the illustrations for some of his books and contributed drawings to Punch, including some ‘big cuts;’ see Price, 38.

2. See Altick, 1997, 122-23. Doyle, who was an Irish Roman Catholic, had studied art at the Dublin Society. He went to London in 1821 and tried to establish himself as a portrait painter. Unsuccessful at that, he transferred his skills to caricaturing Westminster’s politicians. He produced most of his illustrations for his occasional periodical, Political Sketches, (Boylan, 99; Princess Grace Data Set). For examples of his cartoons see McCord, ‘The Image in England: The Cartoons of HB’; Cyril Arlington, Twenty Years: Being a Study in the Development of the Party System between 1815 and 1835; and G. M. Trevelyan, The Seven Years of William IV: A Reign Cartooned by John Doyle. The monogram ‘HB’ with which Doyle signed his work, was made by two sets of his initials, ‘JD,’ one superimposed above the other. This provided him with a certain anonymity and independence; G. M. Trevelyan, 4.

3. For Punch’s ‘big cuts’ see Altick, 1997, 127. Price points out that the full-page cartoon was one of the features taken from the magazine’s French model, Charivari. The reverse side of the cartoon page was left blank, presumably to ensure its quality; see Price, 23. Henry Mayhew was a coeditor with Lemon during the magazine’s inaugural year but soon dropped out.

4. See ‘Le Don Quixote About to Liberate the Galley Slaves,’ in G. M. Trevelyan, Plate LX.

5. See McCord, 63, 70. In Doyle’s ‘Voluntary Tribute,’published in 1835, O’Connell is shown hiding behind a large skull and cross bones demanding money from ‘Poor Pat,’ a passing farmer. McCord, figure 10.

6. The cartoon is signed by Ebeneezer Landells, one of the founders of the magazine, an established engraver of woodblocks and a former apprentice to Thomas Bewick; see Price, 22; Prager, 38; L. Williams, 1997, 74-75.

7. It is not quite clear from the illustration whether or not the peasant is blind. However, the inn behind Mother Goose/O’Connell bears the sign of ‘The Blind Beggar, Good Entertainment for Man and Baste.’ O’Connell’s identity is emphasized by a road sign pointing to ‘Derrynane,’ the Liberator’s estate. See L. Williams, 1997, 77.

8. For Punch’s fondness for the pantomime motif, see Altick, 1997, 118-20.

9. The suggested parallel between Shakespeare’s Caesar and Brutus on the one hand and Hine’s Wellington and O’Connell is at first sight confusing. Although both Irish born, the Iron Duke and the Liberator had never been friends, much less comrades in arms. We are indebted to Owen Dudley Edwards for his suggestion that the ‘assassination’ that Hine had in mind was O’Connell’s success in 1829 when he forced Wellington to accept Catholic Emancipation. In the aftermath the Iron Duke’s most conservative supporters deserted him, and he was forced from office. In Shakespeare’s play the ghost of Caesar appears to Brutus to warn him that he would meet his defeat at Philippi. In the Punch cartoon the ghostly Wellington warns O’Connell that his Repeal movement can be crushed by Britain’s might.

10. The name ‘Rebecca’ was possibly derived from Genesis 24:60, which states that ‘the seed of Rebecca shall inherit the gates of those that hate her’; see Davies, 378. By the nineteenth century there was a long-established tradition in parts of rural Britain and Ireland for men to disguise themselves in women’s dresses when engaged in clandestine activities.

11. This is the first appearance in Punch of a ‘big cut’ signed by ‘Shallaballa,’ whom Altick identifies as William Newman (1997, 344).

12. See Jon P. Klancher, 11-12. Using Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia, Klancher points out how certain words or phrases associated with an outside group might represent a ‘socially alien discourse,’ which reinforces a reader’s sense of cohesion with his own group, in opposition to whatever Other the ‘alien’ language signifies. We suggest that ethnic dialects can constitute this type of ‘alien’ discourse.

13. Altick identifies the Brougham/gamekeeper figure as ‘wearing the incongruous uniform of Widdicomb the ringmaster’ (1997, 345). While the epaulets on the coat could suggest a showman, the top hat, admittedly more battered, could have been worn by an urban rat-catcher.

14. According to Price, Meadows had a finer, more ‘fanciful’ technique than the other Punch cartoonists, as evidenced by his drawing in both the ‘Agitation Farce’ and the ‘Irish Frankenstein’; 42.

15. This figure is a reversal of an earlier cartoon published by John Doyle on 18 January 1831, in which O’Connell is the ‘monster’ and Whig politicians represent a corporate Frankenstein. In ‘POLITICAL FRANKENSTEINS: Alarmed at the Progress of a Giant of their Own Creation’ Doyle depicts a normal-looking but outsized O’Connell striding through a paper proclamation, the type which the Whig Government issued in attempts to abolish the Liberator’s various associations supporting Repeal. See G. M. Trevelyan, Plate XII.

16. Roy Douglas and his colleagues suggest that Meadow’s monster also looks back to the ‘bestial and diabolical’ Irishmen of Gilray’s illustrations of the Irish rebels of 1798; see Douglas, et al., 40.

17. McCord 70. For ‘A SIMPLE QUESTION Asked in “Sober Sadness,”’ see G M. Trevelyan, Plate XLVII.

18. Spielmann identifies this as one of Thackeray’s contributions to the magazine. For the text see Spielmann, 66-69.