Imagining a Famine/Imaginary Famine—1845

As the potato blight spread throughout Ireland in the fall of 1845, the word ‘famine’ was used with increasing frequency in the British press, although starvation had not yet occurred. At that point the word stood for a concept — certainly a frightening one — but not a reality. Britain and Ireland had not seen wide-spread famine since 1740-1741. During the decades prior to the 1840s, starvation and disease had occurred in parts of Ireland when the potatoes failed. Yet, no one in either island had actually seen famine on the apocalyptic scale that the word suggested. British writers used the word thinking they knew what it meant without actually having seen its terrible reality.

Before the possibility of famine could be dealt with, however, its probability had to be recognized. Not everyone was prepared to accept that the potato blight represented a serious threat. To many in Britain Ireland always seemed to have too many people and not enough food, constantly calling upon Britain for aid. Throughout 1845 there was a certain amount of skepticism, therefore, within the pages of some papers regarding the seriousness of the situation. In recognizing what was happening in Ireland, the British press faced problems of awareness, assessment and acceptance.

The problem was not the want of information about Ireland. Since the 1820s, the ‘Irish Question,’ whether that was interpreted in terms of religion, nationalism or economics, had demanded an increasing amount of British attention. By the summer of 1845, there was already a considerable library of travel books, economic and political treatises, articles and parliamentary reports about the country. Parliament itself was periodically preoccupied with Irish issues. Therefore, informed opinion in Britain was aware of the critical importance of the potato for the survival of a large portion of the Irish population. Indeed, enough of England’s and Scotland’s poor depended on potatoes to cause concern even within Britain. While not everyone knew the amount of food Ireland exported to England, most knew that anything that threatened to curtail such shipments could have serious consequences for the price of food within Britain. Discussion of the potato blight in Britain, therefore, fell automatically into a broad economic, and, thus, political context.

The outbreak of the potato blight coincided with the rise of the Anti-Corn Law agitation in Britain. Modeled on O’Connell’s Repeal Association and copying many of its tactics, the movement demanded an end to the tariffs against the importation of foreign grain. The Corn Laws kept the price of food high, angering the urban working class and their middle-class employers, while benefiting the aristocratic landowners. Obviously, any threat to the United Kingdom’s food supply would have major implications concerning the Corn Laws. Any news of scarcity presented a threat to Protectionists, while those in the Anti-Corn Law camp could only see crop failure as a critical leverage in their favour.

The movement to repeal the Corn Laws was itself part of a deeper ideological shift in economic philosophy taking place in Britain. Industrial Britain saw the promise of the future not only in free trade but also in freedom from all forms of government intervention. Individuals striving for their own best interests, restrained only by laws protecting life and property rights, would inevitably produce the best society, morally as well as economically. The laissez-faire doctrine of political economy enjoyed the dynamics characteristic of emerging ideologies. It had gained considerable ground, especially among middle-class Whigs. Inevitably, ideas based on political economy would shape the British government’s response to famine in Ireland.

Another political factor that would influence British responses to the growing crisis in Ireland centered around Daniel O’Connell and his Repeal Movement. O’Connell and Repeal had generated a good deal of ill will in England, not only towards the leader but also towards his supporters as well. The Irish peasantry, who swelled the ranks of the Liberator’s mass meetings, represented those most at risk from the destruction of the potato. O’Connell, for his part, could be expected to try to turn any problems in Ireland into grist for his Repeal mill.

Thus, it was not merely that the potato blight had to compete with other kinds of news. When Phytophthora infestans began to spread through Ireland’s potato fields in the fall of 1845, this ecological disaster had to be, first, recognized, then absorbed and interpreted within a political environment sharply divided along national, party and ideological lines. Even the recognition and description of what was happening inevitably became a political act.

Ironically, the potato blight hit Ireland at a time when the United Kingdom was enjoying generally good grain harvests. The poor crop yields of the earlier part of the decade were momentarily gone, and in 1845 the grain did very well on both sides of the Irish Sea. The Standard for 9 September, reporting on the grain harvest in Leinster, Ireland’s eastern province, gave a glowing picture. ‘We have now enjoyed more than a fortnight of uninterruptedly fine harvest weather, and the progress made in saving the grain crops is consequently exceedingly gratifying…. [T]he deepest gratitude pervades the hearts of the farmers for the bountiful dispensation of a gracious Providence’ (6). Much of Irish grain was, of course, destined for export to England.

Even in mid-summer most of the potato plants looked healthy, as did some of the early tubers. The initial newspaper reports concerning the crop were quite positive. The Morning Chronicle’s correspondent in Dublin wrote optimistically on 30 August, stating, ‘The weather is exceedingly fine; the accounts of the crops from all parts of the country are most favourable…there never, perhaps, was a finer growth of potatoes, which are selling at about half the price of this time last year.’ By that time, however, the first Irish sighting of the potato blight had already been recorded in the Dublin Botanical Gardens on 20 August. The following week the blight appeared in County Fermanagh (Campbell, 21). In the beginning of September the Scotsman quoted the Dublin Evening Mail to the effect that while the hay and flax harvests were excellent,

The potato crop, however, is far from satisfactory. There appears everywhere a great abundance, but in several districts, a rot has set in, and two-thirds of the tubers are found to be rotten within, though large and well looking without. [In the worst locations] four men, it is said, would scarcely turn up a cart-load of good potatoes in the course of a day’s work (Scotsman, 3 September 1845, 3).

A week later, the Morning Chronicle published a clipping from the Newry Examiner that also contrasted the generous grain harvest to disturbing signs in the potato fields.

County Louth…. The potato crop, we regret to say, is giving up fast — many fields becoming withered prematurely. The quantity planted, however, exceeds anything of the kind for many years. They will not, however, be near so productive as the crop of last year (12 September 1845).

On the same day, the Standard reported a partial failure of the potatoes in Ulster, although the crop was said to be abundant in Cork and the western counties.

The Times was slow to pick up the story. Through much of the early fall of 1845 the paper’s readers would have found its coverage of Ireland quite familiar: God (a Protestant) was in His heaven; Thomas Campbell Foster was still harrowing the Irish bogs, finding more sinners than saints; and there were, as always, reports of violence. On 10 September The Times’ report on Ireland began with an account of the military intervention in a conflict ‘between the races’ in Cavan. ‘Loyal Protestants’ were preparing to use force to oppose the marching bands of the (Catholic) Abstinence Society, from whom the writer of the article withheld the ‘loyal’ label.

The last item in The Times’ report from Ireland concerned claims of those made destitute by accident or injury at the hands of the British constabulary. During an incident following a fair in Ballinhassig, eight people were killed when the constables, thinking themselves under attack, fired into a fleeing mob. The Mayor of Cork was reported as having asked Sir Robert Peel for some relief of the Ballinhassig sufferers, ‘for some pecuniary assistance from the Government for these destitute families.’ The Times then printed a letter from ‘Treasury Chambers’ recording the refusal of compensation to the Irish victims. The writer of the letter stated, ‘I have it in command to acquaint you that, however much this case may call for the sympathy of private individuals, it is not one to which their Lordships would be justified in applying public funds’ (The Times, 10 September 1845). The letter was signed by Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, who demonstrated to The Times’ readers, including virtually every member of Parliament, that the correct government response to an Irish request for public assistance was ‘No.’ Even Trevelyan could not have imagined the number of opportunities he would have to repeat the exercise.

On the same day, 10 September, the Manchester Guardian ran a piece titled, ‘DANGERS OF A DEFICIENT HARVEST,’ speculating about higher food prices due to the blight. The paper announced that the imports of wheat from Ireland were noticeably lower than usual, probably because the European markets were taking a larger share to compensate for potato failures on the Continent. The paper was not optimistic about the prospects for the future.

From Ireland we draw a part of our daily bread. But it is evident how precarious is that dependence…. As Ireland may truly be considered in a perpetual state of famine, she should rather import from foreign countries than export to us. Her wheat, and barley, and oats, are the rents of absentees. Could we be sure that it indicated a greater home consumption, we should, under her peculiar circumstances, congratulate her on the results of the present return (Manchester Guardian, 10 September 1845, 3).

At this point, however, the situation in Ireland was still sketchy. A week later the Manchester Guardian stated that, while the news of the failure of the potatoes in France was disturbing, ‘happily there is no ground for any apprehension of the kind in Ireland. There may have been partial failures in some localities; but we believe that there was never a more abundant crop in Ireland than there is at present, and none which it will be more likely to secure’ (17 September 1845, 5).

The protectionist Standard did its best to maintain an optimistic tone, quoting an Irish paper that hoped that

the lower classes of our population may be spared the additional misfortune of having one of the greatest blessings of the country dashed as it were, from their grasp, at the moment when every voice was raised in congratulation for the comfort and plenty which it seemed to ensure for another year (18 September 1845, 3).

Apart from scattered reports, questions concerning Ireland’s potato crop did not dominate the news in September. The topics in the Morning Chronicle’s report from Ireland for 13 September included the Orange Order, Maynooth College, the Ballinhassig relief fund, the Harbour Commission at Cork, the Protestant/Catholic conflict in Cavan, and the Repeal demonstration of 20,000 to 30,000 people in Bruff, during which there reportedly were calls for violence from the crowd.

The fact that the blight was wide-spread but not universal in Ireland clouded the picture. Even by the end of September conditions still seemed mixed. The Morning Chronicle of 29 September published reports from all around Ireland. In Galway, ‘potatoes are abundant and good;’ in Tralee the reporter was ‘not aware of blight in the county.’ However, in Athlone there were ‘some complaints of the potato crop, but not so much…as in other parts of Ireland.’ Londonderry had no failures, though on the Innishowen peninsula of Donegal ‘several fields have suddenly assumed a sickly hue.’ In Tuam there seemed ‘no cause for apprehension.’ Nevertheless, reporting in the same issue on the effect of the blight in Prussia, the journal described the newspapers there as containing ‘deplorable’ accounts of famine. The Morning Chronicle looked ‘to the future with sorrowful foreboding.’

The News of the World optimistically reported that ‘The take of herrings all along the west coast of Ireland is so immensely abundant, that the people cannot procure salt in sufficient quantity to save them…. So that amongst the many sources of food which Providence has so bountifully supplied this season, the people will be provided with a large stock of this delicious fish’ (5 October 1845, 2e). The paper did not explain how people were to preserve the fish without a ‘sufficient quantity’ of salt, a chronic problem in the west of Ireland.

At the beginning of October the fear of famine in Ireland was barely mentioned. Within the next two weeks, however, the evidence of serious crop failure began to accumulate. Although its Dublin correspondent in the 17 October issue of the Standard bravely reported that ‘the accounts received in town today are less desponding than they were towards the close of last week,’ his lines appeared under the heading ‘The Potato Disease.’ According to the article, by simply separating healthy from stricken tubers the progress of the disease could be checked (12). On the same page under ‘Weather and Crops’ appeared a notice that heavy rains in England were affecting the late harvest of grain and beans.

As the news from Ireland got worse, some writers began to speculate on the consequences of a serious shortfall in the food supply. On Sunday, 19 October 1845, the lead article in the Observer addressed ‘that most vital of all questions, the food of the people — in fact the means of sustaining life among millions of our humbler fellow-beings.’

Should…information show that the public safety requires energetic action, no party considerations or monopolist clamours will, we are confident, be suffered to influence their deliberations. Famine, with all its attendant horror, glares at them from Ireland. There are those who think that the accounts from that country exaggerate the failure of the staple food of its people; but…in Belgium…two-thirds of the early crop and five-sixths of the late potato crop have been destroyed…if the food of the millions in Ireland has perished to only half that extent, what a frightful prospect we have before us. A famine is certain, and what then?

In answer to this disturbing question the writer firmly stated:

Heretofore English charity, Saxon benevolence, has striven to interpose between the starving wretches and their graves. [Before] Poor Laws in Ireland…the Irish absentee landlord who subscribed a few pounds to the relief fund, whilst he extracted thousands from the very scene of starvation, passed before the world as a most humane man. Now…the British public…will naturally say that those who have grown rich by extractions from these poor creatures, should maintain them in their destitution. Moreover, there are now Poor Laws in Ireland, and to them the pauper population must look for refuge and support. From English charity, therefore, there is little to expect in alleviation of the threatened famine…(Observer, 19 October 1845, 4).

The ‘Saxon benevolence’ invoked in the first sentence leaves the reader to fill out the ‘Celtic’ side of that equation with the greed of Irish landlords and who knows what culpability on the part of the ‘starving wretches’ themselves.

The significance of the Observer’s article lay in what it anticipated, as well as in what it failed to foresee. Although the writer was mistaken about the English people being unwilling to help the Irish, he was quite right in warning that ‘Saxon’ charity had its limits. In stating that the Irish landlords would have to shoulder the burden of any relief, an idea that had surfaced during the earlier debates over the Irish Poor Law, he was anticipating future government policy (Macintyre, 209). When, however, the writer shifted his attention to the potential effect of the Irish crisis on the food supply in England, he was wrong. ‘Ireland has for years proved a fruitful granary to this country…. This year the supply of corn to the British markets must be materially diminished, if not entirely cease unless, indeed, the Irish themselves be abandoned to starvation’ (Observer, 19 October 1845, 4). Warning that there would be a shortfall in Irish food, the Observer anticipated that Ireland would keep its grain at home. This would reduce England’s grain supply, and prices would rise as a consequence. Thus, the paper could, presumably in good conscience, exempt English charity from responding to Irish needs, because it assumed that Irish food would stay within the country. At this point in 1845 the alternative of allowing the Irish to starve was unthinkable. The Observer’s editorial was praised in other papers as a ‘semi-official’ declaration of policy, an honour that the paper denied the following week, wisely, as it turned out.

There were other calls to keep Irish agricultural produce at home. Thomas Blake, a justice of the peace in Galway, wrote to the Morning Chronicle insisting, ‘that nothing short of a restriction on the exports, a suspension of the distilleries, and an opening of the ports [to foreign grain] will provide for this emergency’ (5 November 1845, 5). The same policy had been espoused in a letter to the editor published in The Times in October under the heading ‘Irish Famine.’ The writer, ‘T.S.’ of Liverpool, argued for the suspension of the Corn Laws in favor of free trade and for ‘an embargo on the export of provision from Ireland.’

Let the [Irish] people keep their produce this year, and let the Government settle the matter of rents with the landlords. Some three or four millions might do it. We were charged 20,000,000l to free the negroes, — shall we not be charged three or four [million pounds] to save from perishing a much greater number of our near neighbors and brethren? (The Times, 29 October 1845).

The twenty million pounds referred to was the price paid to the plantation owners in the British West Indies in compensation for the liberation of their slaves. Even the word ‘brethren’ echoed the abolitionist’s language. While probably unintended, the letter, nevertheless, invited a comparison of the Irish to the former slaves, exotic colonial populations on distant islands, powerless and totally dependent upon mercy from the metropolitan centre.

In calling for relief of Irish hunger, ‘T. S.’ called attention to a potential problem. He suggested ‘a distribution of the provisions,’ but then asked, ‘How is that to be done? They have scarcely the machinery for such an exigency, but it ought to be prepared, cost what it may’ (29 October 1845). Indeed, barely part of a cash economy, the small tenants in the west of Ireland were too poor to purchase grain, even if it were made available to them. It is interesting to note that these questions were being raised by a resident of Liverpool, the city destined to be most affected by the tens of thousands of famine-driven Irish who would pour into England over the next few years.

By mid-October the blight seemed to be spreading throughout Ireland, although some papers continued to hesitate to declare a disaster. Note the uncertain account in the 20 October issue of the Morning Chronicle: ‘The accounts yesterday were extremely afflicting, showing that the disease in the potato crop had extended to several counties — for instance, Galway and Tipperary — where, up to this time it was not known. There is now scarcely a county in Ireland free from the disease….’

Yet, the same issue of the Chronicle carried a report from a Cork paper that, in its convoluted language, reflected the reluctance, even among some Irish editors, to admit the extent of the loss of Ireland‘s potatoes. ‘The intelligence respecting the murrain in the potato crop, which has reached us since our last publication, presents no features calculated to allay the apprehension of scarcity which its first appearance amongst us naturally awoke’ (Morning Chronicle, 20 October 1845).

Two days later, however, the Manchester Guardian published a blunt report from the Dublin Evening Post.

There is no blinking the matter any longer. What was at first apprehension is fast becoming alarm. We shall hear no more silly gibes against persons who like ourselves, endeavoured to turn the public attention to this subject, at an early period — and, as it has now turned out, not a whit too soon. In truth it is no joking matter now…it appears that potatoes are being shipped in large quantities from the port of Dublin for Holland and the Low Countries…. [T]his operation should be stopped at once (Manchester Guardian, 22 October, 1845, 5).

Although the first item concerning Ireland in the 24 October issue of The Times was entitled ‘The Potato Distemper,’ the paper continued to question the seriousness of the situation. Alderman Gavin of the Dublin Corporation was quoted as saying that statements about the potato blight ‘were frightfully exaggerated….[Ireland] could afford to lose a quarter of the present crop without the poor suffering.‘ Gavin was sure that ‘the alarm had been raised to get up the price of corn.’ The Times added that ‘The Cork Reporter…announces some slight improvement in that extensive district’ (24 October 1845). The words ‘slight improvement’ seem to suggest that the potato crop, like a convalescent patient, was recovering.

Even towards the end of the month contradictory reports continued to appear, sometimes on a single page. On 29 October the Morning Chronicle published two pieces from the Sligo Champion. One maintained that ‘The damage in this county is grossly exaggerated, as every farmer must know; but then it is in the interest of the farmers to make things appear in their worst form, for any movement in that direction has the obvious tendency of raising the markets’ (6). Yet, on the same page, there appeared a letter, also taken from the Sligo Champion, written by a Reverend John Coghlan, presenting a doomsday scenario:

It is utterly impossible to convey to you a true picture of the alarming state of despondency into which the people of this parish have been thrown by the extensive rot in the potato crop. It is quite common that a potato field…today may be good and sound, and in three days after in a state of melancholy putrefaction…. [T]hose poor creatures who depend altogether on the con-acre potatoes for support, now left without any resource…have neither oats, nor money, nor potatoes…. May God in his mercy relieve them and revert this scourge from our already impoverished, destitute and suffering people (6).

It would have been difficult, however, to credit such dire predictions in the face of the News of the World’s account of the Marquis of Hertford’s ‘dejeuner’ for his tenants near Lisburn, County Antrim. The harvest feast included

seventy dishes [of] baked and roasted beef, fifty five ditto mutton, ninety seven joints boiled beef, ninety six tongues, one hundred and ninety two meat pies, seventy turkeys, seventy two geese…3,600 pounds of bread, 3,200 pints of strong ale. Thirty barrels of beer, thirty two gallons in each barrel. One hogshead and six half gallons of ale and porter…3,200 bottles of Punch (cold), and a cask of cider (26 October 1845, 2d).

The Marquis owned one hundred imperial square miles of land containing about two hundred townlands and four thousand tenants.

Nevertheless, as the reports of the spreading blight accumulated, some leader writers in Britain began to voice severe forebodings for the future — forebodings better founded than anyone could have known. In late October the Scotsman noted:

The blight…has been spreading and growing more inveterate year after year, and has baffled all efforts of science and experiences. Good seed for the next crop will be scarcer than ever before, and the chances of another failure proportionally increased. In short there is too much room to fear that a chronic and irreducible disease has attacked this important product [the potato], and that we may consequently reckon upon a large deduction having been made from the supply of food, which can only be filled up by an increase in the quantity of grain available to consumers (Scotsman, 25 October, 1845, 2).1

The more such fears spread, the more the question of famine in Ireland became caught up in the battle over protection. The Corn Laws, so protectionists believed, kept the price of wheat and other grains high to the benefit of the entire British economy, especially the largest landholders, the British aristocracy. Protectionists feared that opening British ports to an influx of tax-free foreign grain would cause prices to fall. The Anti-Corn Law forces among Liberals and Whig middle-class Radicals saw the food crisis as the opportunity to finally attain free trade.

In the same issue in which it called for ‘an increase in the quantity of grain available to consumers,’ the Scotsman reprinted a piece from The Standard of Monday, 19 October, announcing it was breaking ranks with the Protectionists. The Standard also alluded to a rumor that the Ministry intended to ‘open the ports,’ i.e., reduce or eliminate the duty on grain, by an Order in Council.

The ultimate consideration — that to which all other considerations must give place — is the duty of the state to insure that not one of the Queen’s subjects shall perish from famine…. Sir Robert Peel, we are convinced, is not the statesman to shrink from the most urgent of all a statesman’s duties — the preservation of the lives of his fellow-citizens…. In the supposed case of a very great deficiency of the potato crop, it seems pretty plain that a suspension of the Corn-law ought to be resorted to (reprinted in the Scotsman, 25 October 1845, 2).

On 26 October 1845, the Observer cautioned, however, that ‘The sudden repeal of [the Corn] laws would be destructive. The gradual abolition of them would be less injurious…. We feel…the danger of sudden changes in a community so purely artificial as ours is….’ The sense that British prosperity was a fragile thing, maintained by the ‘purely artificial’ Corn Laws, made any abrupt change seem threatening and an excuse for caution. For a time this wary prudence seemed to govern the reaction of Peel’s Government to the blight. Although Peel was moving privately away from protection, the majority of his Tory party, founded on the landed interests, remained tied to the Corn Laws. Thus, the Government seemed unable to act. The leading article for the 16 November News of the World carried a partisan attack on both the Peel ministry and on the Tory Irish landlords, whom it characterized as ‘remorseless, kindless, pitiless villains.’ The leader, titled ‘The Politician,’ accused the Government of self-congratulatory posturing over what had seemed an abundant fall harvest.

It was in the midst of the triumphs of the Tory press — in the midst of the overwhelming gush of prosperity that seemed to come rushing down upon all classes, that a few short paragraphs appeared in the Irish papers, stating that in some places, it appeared a blight had come upon the potato crop. We marked these at the time as an indication of an approaching change (italics original).

The News of the World mistakenly insisted that the Irish potato crop had been ‘utterly consumed by the blight,’ and the paper seemed to welcome this disaster as something the Tories richly deserved. Trumpeting ‘famine’ in Ireland, the writer condemned the Peel administration for its inactivity in the face of a crisis. However, this paper, like others before it, insisted that, with the proper legislation, Ireland could sustain itself.

The Irish people have said this — ‘without relief, from external sources, the peasantry must starve.’ It is not fitting that Ireland should become a beggar to England — or that the English people should be called upon to contribute to their maintenance, when Ireland has resources enough to meet the emergency — when she grows food enough to feed her own population, and is rich enough for their support. You have upwards of £70,000 a-year from the Crown lands in Ireland. Mortgage that income — raise upon it at least £200,000 — apply that sum in support of the poor, let Irish money feed Irish poverty. If that be not enough let every estate held by an absentee proprietor be heavily taxed…. Let the land which is rich enough to give such wealth, have the source of that wealth detained there, that it may aid to support those by whose toil the wealth is produced… (News of the World, 16 November, lc; italics added).

This sort of enforced self-reliance for Ireland represented a policy that would become the most convenient and least expensive solution for England.

When The Times did seriously address the pending crisis, it drew attention to what it feared might be an unnecessary drain upon England’s limited resources. The leading article for 6 November exclaimed:

It is no use for men, whether in the Cabinet or out of it, to disguise or to understate the magnitude of the impending danger. It is no use for them to argue that, because wheat is cheap in England, there is no chance of famine here; or that the failure of the potato crop in Ireland cannot affect the corn markets in this country…. Under any circumstances, therefore, it is reasonable to anticipate that before the period of another harvest arrives, the staple food of all classes will have become dear.

The Times then rhetorically asked Sir Robert Peel, ‘Will you vote money to give employment to the Irish people?’ As the situation worsened, Ireland would demand employment so that her people could buy food. However, The Times’ leader writer could not imagine any relief scheme for Ireland that would not be an unprincipled opportunity for ‘jobbing’ or corruption

It would be an act of munificent charity, if it were not (as it probably would be) perverted into a monstrous job [fraud]. But remember, if you do this, you will be taking away the money of the English people at a time when money will be scarce, and employment much rarer than it is now, to feed the Irish. Will this be just? Do you think it will be tolerable?

As in answer to its own question, The Times claimed to see an alternative on the horizon.

No. A great opportunity has arrived…for regulating the machinery of commerce, preventing great uncertainties in the price of bread, and the great embarrassments which follow its scarcity. This is the age of low prices. Our prosperity is now found to be coincident with low prices…. Sooner or later, restrictive duties must be narrowed to their lowest limit (6 November 1845).

Since the people would prosper under free trade, surely, the leader writer argued, ‘That which enriches all besides cannot beggar a landed aristocracy.’ The Times now proclaimed that the solution for high bread prices was the repeal of the Corn Laws. The paper’s leader concluded that ‘the present corn laws are doomed’ and called for Peel to resign if he could not ‘sign the warrant of their execution.’2

As The Times moved toward a free-trade position, it became more open to recognizing the crisis in Ireland. The leading article for 8 November employed short, emphatic statements in place of the paper’s customary rolling sentences of classical length. Delane’s leader attacked Peel’s apparent policy of wait and see:

The emergency is pressing. Corn is becoming dearer. The wheat which was in our granaries is being transported to Holland and Belgium…. Famine threatens Ireland; scarcity is already apprehended in Scotland. Yet the Minister [Peel] delays…. He will linger on a few weeks longer, until the prices of provisions rise, popular impatience is aroused, and a general panic prevails. He will then issue an order, which will have the effect of draining the bullion of the Bank, to outbid foreign hunger, and glut foreign speculation (The Times, 8 November 1845, 4).

Meanwhile, Thomas Campbell Foster kept up a drum beat of assertions that Ireland, left as it was, was unimprovable and ungovernable. In a report written from Thurles in County Tipperary, Foster painted a picture of the seemingly irresolvable contradictions in Irish life:

You have here the richest land and the most extreme poverty. The people complain of high rents, and yet extract but half the profit out of the land which it will yield. They struggle desperately to possess a patch of land, because they have no employment by which to live…. They shoot one another in the struggle to possess a patch of land, and leave neglected thousands of acres which would amply repay their labour and capital…. They complain that landlords and agents in parts of the county will not reside, and they shoot them if they do (4 November 1845).

Foster went on to wonder, ‘Has the effect of bygone neglect, and mismanagement, and wrong generated a self-defensive resort to suspicious obstinacy, and violence, and fraud?’ The Times and Foster kept up the attack upon potato subsistence in Ireland, a critique that owed less to the cold logic of orthodox political economy than to moralistic outrage against those deemed responsible for such an ‘unnatural’ state of society. In October and November 1845 leader after leader castigated potato cultivation and insisted that those dependent upon it were in a debased and savage state.

The Morning Chronicle, on the other hand, offered at least one reason for aiding the Irish: ‘Men can well see that the five or six millions of labourers in Ireland, whose supply of food is threatened to be cut off, can be but poor customers for the calicoes and fustians of Manchester and the woolens of Yorkshire’ (22 October 1845). Following sound economic logic, the paper insisted that England’s manufacturers needed Ireland’s market. Keeping the Irish economy afloat in the face of food shortages would be in England’s own economic interests.

As the specter of hunger loomed in Ireland, the British press began to speculate on the possible escalation of unrest, especially in the counties of Tipperary, Westmeath, Limerick, Offaly and Clare. The murders and attempted murders in these counties were news for papers of every political persuasion. While most British papers were enraged, the Morning Chronicle quoted testimony from the Devon report to the effect that when small farmers and laborers were evicted, ‘They grow demoralized and savage, frantic and wild…the wretchedness of their condition is such that many of them would consider it a happiness to be hung.’ For a clincher, the Chronicle quoted the Bible: ‘Oppression maketh even a wise man mad.’ Yet, the paper had to admit that most of those living on potatoes and water seemed rather tame (8 November 1845, 6).

The Observer for 1 December quoted the Morning Herald’s leading article on the subject of Irish violence:

What chance of success…for a repeal rebellion? What chance would three or four millions of the most ignorant, barbarous, and uncouth of the human race, without leaders, without discipline, without arms, without a penny of money, have against the mighty power and boundless wealth of England, wielding the strength of more than 24 millions? It is right that these things should now and then [be] referred to, because the whole policy by which the plunderers of the Irish poor succeed in their robbery goes to create an impression that a rebellion might be successful (quoted in the Observer, 1 December 1845, 2).

Rising above the tabloid news of assassination attempts, the Scotsman’s editorial for 12 November 1845, returned to the basic question: ‘AT WHOSE COST SHOULD THE IRISH DISTRESS BE RELIEVED?’ The writer argued that ‘if a large proportion of the people, even in good years, have an insufficient supply of food, it is plain that a small deduction from that supply must expose multitudes to the horrors of famine.’ The paper argued, however: ‘Since 1800, she [Ireland] has received no less than three millions sterling from Parliament either to feed her suffering population, or to give them employment.’ More interested in politics than in charity, the writer objected that ‘The notion of stopping the repeal cry by largess from Saxon benevolence, is like stemming the ocean with a bulrush’ (italics added).

The Scotsman’s leader contained a double-barreled argument that questioned the idea that Ireland was heading toward a real crisis. First, it claimed that short-falls in the food supply were regular occurrences. The paper asserted that, ‘according to returns obtained four or five years ago, there were 2,300,000 persons in Ireland who had no means of subsistence but charity, and this was described as the ordinary condition of the country.’3 Secondly, the sounds of distress heard from Ireland were only a ‘repeal cry.’ In other words, Irish hunger was nothing but politics. Any attempt to ameliorate what was essentially a political problem by providing public relief was doomed to failure. The only remedy the Scotsman‘s writer could suggest was ‘that the time has come when Ireland (and Scotland too) ought to provide for the relief of its own poor both on ordinary and extraordinary occasions’ (12 November 1845).

By November the ‘people’s crop’ (potatoes planted in summer and dug in late fall) had been lifted, and the extent of the disaster had become clearer, although it was still the anti-protectionist papers that were most likely to trumpet the danger. The Morning Chronicle’s correspondent in Ireland accurately explained the situation facing the Irish farm laborer.

He had planted his crop last, having helped the farmers with their planting. The blight, ‘fastening on the tuber while growing, the disease grew with the root, and in almost all instances where the poor man’s garden was dug, it was found that the crop was not only moist and flavorless, but absolutely unfit for human food’ (14 November 1845).

In its 19 November 1845 issue, the Morning Chronicle, now apparently eager to keep up pressure against the Corn Laws, reported on ‘The Potato Famine in the South of England.’ In the same issue the Whig paper accused the Galway Evening Mail of being a blatantly ‘Tory organ’ for declaring that ‘the potato panic shrinks in before the test of truth and the precautions of the government.’ The Chronicle’s leader complained that the whole object of the Evening Mail was ‘to encourage the landed proprietors of Ireland to resist any attempt to open the ports, to keep their own hands in their pockets, and to throw the onus of supporting the impending misery upon the public coffers, or, as the phrase goes, upon the “government”….’ The writer argued that Ireland’s only hope lay in lifting the tariff on foreign grain and opening the ports to the international grain trade. The paper also suggested that Irish landlords should forego their rents for a year.

In fact, several major landlords did reduce their rents. A few even declined to collect them. Among these generous proprietors was Lord de Freyne, whose concern for his tenants was reported to the Morning Chronicle in a letter written by the Rev. John Coghlan:

A report creditable to Lord De Freyne has been circulated among his numerous tenantry — that he has sent them orders not to dispose of any of their oats until they can see the exact extent of their loss, and that his lordship will not call on them for rent until God in his mercy may avert this awful calamity from his people…. If the oats be permitted to leave the country, how will the people subsist? (27 October 1845).

In Roscommon, according to the Morning Chronicle, Nicholas Balfe of South Park ‘generously forgave every tenant on his extensive estates one half-year’s rent.’ However, the paper also reported that ‘The glut of pigs in this [winter’s] fair is justly attributable to the conduct of the landlords in exacting their rents’ (10 December 1845, 8). The fact that there were no surplus potatoes to feed livestock over the coming winter was another reason why pigs and cattle were plentiful. The ‘glut,’ of course, translated into low livestock prices, hurting both tenant and landlord.

Thomas Campbell Foster may have contributed to the wide-spread criticism that the Irish were not harvesting their ruined crop or doing all they could to dry and preserve the diseased crop. However, the Morning Chronicle writer attacked the Evening Mail for expressing a similar attitude and indirectly criticized The Times’ stance as well:

The Irish Tory organ says the people are dogged and reckless, and that they will not take advice, nor adopt precautions to preserve any portion of their crops. This is not true. On all sides they are to be seen carting their potatoes into houses, which it is not usual to do until an advanced period of the spring; their women and children are employed constantly in turning them over, and separating the bad from the good; but the disease, which has been well compared to a gangrene, is not to be checked by any means at the disposal of the poor Irish peasantry…. [T]he means of exposing [potatoes] on a dry floor to a free current of air, which appears to be the only effectual way of arresting the progress of decay, they do not possess (Morning Chronicle, 19 November 1845, 5).

Daniel O’Connell, who followed the progress of the blight closely, seemed uncertain about the extent of the crisis in early November. He is reported to have told the Citizen’s Meeting he assembled in the Music Hall, Lower Abbey Street in Dublin, that on his estate at Derrynane, only one-sixth of the crop had been lost. He read a letter from his son ‘which is more cheering than desponding.’ Politics was still his main interest, however.

The report of Lord Devon’s commission allows that 4,500,000 of the Irish people have no land but the land they grow potatoes upon, and no provision to live upon but the potato [hear, hear]…. It may be said if the Irish give the English their oat crop they receive the money of the English in return, but the money does not come to Ireland. It goes in the payment of absentee rents, and neither oats nor money come back to Ireland [hear, hear] (Morning Chronicle, Monday, 3 November 1845, 6).

Naturally, the Liberator’s solution to the problem was the re-establishment of an Irish Parliament, which, he argued, would draw the absentee landlords and their wealth back to Ireland.

O’Connell’s Citizen’s Meeting then drew up a series of recommendations to be presented to the Lord Lieutenant. According to the Morning Chronicle, these included closing the ports to keep Irish grain in the country, as well as shutting down the distilleries. Through such measures Ireland could deal with the crisis without outside help. The paper reported Lord Cloncurry as stating, ‘He was no advocate of the principle of appealing for succour to other lands, while there was as much money going out of Ireland as would, if retained in it, make it the garden of Europe [loud cheers] (Morning Chronicle, Monday, 3 November 1845, 6). Two days later, on 5 November the Morning Chronicle reported Dublin Castle’s rebuff to the idea that any policy concerning Ireland should originate in Ireland. According to the paper, ‘the Lord-Lieutenant declines to take any step, leaving it to the Ministry who are the responsible advisors of the Crown, to adopt any measures which may be required by the emergency’ (5 November 1845, 5).

Lord Cloncurry, a Repeal supporter, then wrote directly to Sir Robert Peel, recommending a seven-point program. This included removing the tariff on grain, prohibiting the exportation of oats, reducing the consumption of oats by the army’s horses in Ireland, and suspending distillation. Cloncurry also urged a loan to Ireland in order to subsidize food prices. He wanted granaries to be built to store wheat, oats or maize at each of the poor-law unions. He also called for a system of public works to give employment and, thus, provide a cash economy in the west of Ireland for the purchase of grain supplies. As reported in the Morning Chronicle, Peel merely acknowledged receipt of the letter (14 November 1845).

During the growing debate over the possibility of famine in Ireland, Delane and his ‘Commissioner,’ Thomas Campbell Foster, apparently decided to ignore the impending food crisis and focus all their efforts on the politics of Repeal by attacking Daniel O’Connell on his home ground. Foster’s initial report on ‘Mr. O’Connell and his wretched tenantry’ was posted from Kenmare in County Kerry on 10 November. Foster chose to characterize O’Connell’s generosity as a landlord as a prime example of mismanagement:

…[A]ny tenant who applies to him may have leave to erect a cabin where he pleases. He permits subdivision to any extent. This wins a certain degree of popularity; but the land under lease by him is in consequence in the most frightful state of over population…and the poor creatures are left to subdivide their land and to multiply, and to blunder on…. The distress of the people was horrible. There is not a pane of glass in the parish…In not one in a dozen [cottages] is there a chair to sit upon, or anything whatever in the cottages beyond an iron pot and a rude bedstead with some straw upon it; and not always that…. (Foster, 396-397).

Foster insisted that ‘In future…it will be remembered that amongst the most neglectful landlords who are a curse to Ireland, Daniel O’Connell ranks first — that on the estate of Daniel O’Connell are to be found the most wretched tenants that are to be seen in all Ireland’ (The Times, 25 December 1845, 5).

O’Connell did, in fact, allow destitute tenants evicted from neighboring estates to settle on his land. Defending his father, Maurice O’Connell, Derrynane’s manager, wrote to The Times, emphasizing the ties between the O’Connells and their tenants.

Is it for not evicting these people…that he is censured?…Or is it for not applying some Malthusian anti-population check…? Most of these people formed the seventh generation of their families who had held those farms under ours. Was no feeling of pity to be entertained toward them? (20 December 1845, 3).

Maurice O’Connell invited Foster to visit Derrynane rather than to have him invent descriptions of it. Foster arrived in December, and in a letter to The Times, published on 2 January 1846, Maurice O’Connell described the ‘Commissioner’ as ‘sulky as a bear with a sore head and as thorough a specimen of a cockney as ever clipped the Queen’s English’ (3). However, Foster was not alone on this visit. Delane, perhaps sensing that Foster’s column had drawn blood, or at least readers, decided to send W. H. Russell, who had reported on the State Trials, to make an ‘independent’ assessment of O’Connell’s estate. In the words of The Times’ official history, Russell ‘confirmed the accuracy of Foster’s account’ (10). On 6 January Foster crowed that Daniel O’Connell’s ‘disgrace…[would] stick to him as long as he continues to be the curse of Ireland, and…mar her prosperity with his sordid agitation.’

The furious exchanges of November, December and early January between Foster and the O’Connells may have increased the circulation of The Times.4 The Illustrated London News and the Pictorial Times also found news value in accusations that the Liberator was the worst landlord in Ireland. The ILN had occasionally treated O’Connell with some respect. In its 10 January 1846 issue, however, the weekly journal entertained its readers with ‘Views of the O’Connell Property in Ireland.’ The text included extensive quotes from The Times’ ‘Commissioner,’ ridiculing O’Connell’s poorly kept, under-capitalized estate as proof of his inability to administer his own land, much less govern an independent Ireland. The wood engraving of the ‘Interior of Culvane’s Hut’ at Derrynane showed little beyond a box bed to the right of the fire, some baskets, four people, two cows and a pig. Referring to O’Connell’s tenants, the accompanying article stated:

Unaided and unguided, the poor creatures are in the lowest degree of squalid poverty…the cabins are thatched with potato tops…the doorways narrow and about four feet and a half high…many [cabins] are without any hole for a window at all; a cow or a pig was usually inside, and a half a dozen children; the cottages inside were almost invariably quite dark and filled with smoke…through the thick smoke…[one saw] half-naked children, pigs, cows, filth and mud (Illustrated London News, viii., 10 January 1846, 25).

The Illustrated London News article waggishly added that Mr. O‘Connell was not the ‘lord of the soil, but of the rocks and boulders.’ Pictures of Irish poverty, such as these and previously published illustrations, reinforced in the minds of British readers images of carelessness and squalor that would doubtless influence their reactions to later pictures and descriptions of the Famine.5

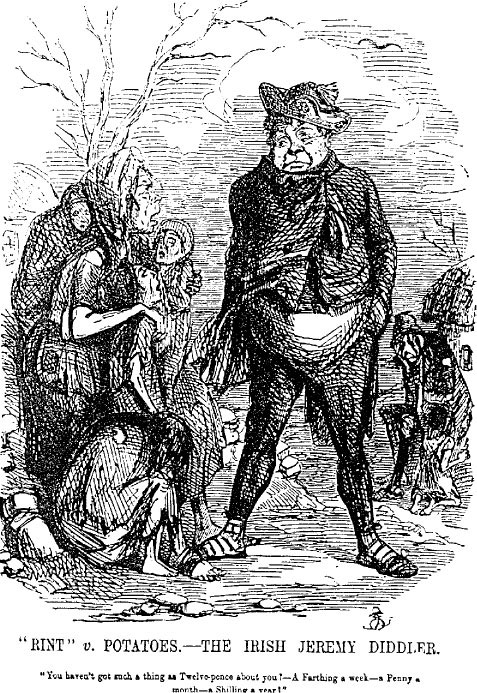

Punch enthusiastically joined the attack on O’Connell. In a November same issue, John Leech’s ‘“RINT” v. POTATOES. — THE IRISH JEREMY DIDDLER’, casts O’Connell begging for his ‘rint’ (Figure 5.1). His hands in his pockets, his belly poking above his pants, Diddler/O’Connell asks a starving Irish mother with her pathetically thin and ragged children, ‘You haven’t got such a thing as twelve-pence about you? — A farthing a week—a penny a month — a shilling a year?’ In the background a man holds his head in despair while a thin, barefoot child kneels pleadingly before him. Even the tree behind the woman is thin and bare.6

Although Leech intended to depict a sense of want in his peasant characters, their upper lips are elongated, as is O’Connell’s, giving them all a simian cast. In fact, starting in 1844, Punch’s caricatures of O’Connell became more distorted, the face and body fatter, the eyes set in a shifty squint, the upper lip more pronounced, the elongated mouth compressed in bitterness. Punch ended the year with ‘THE REAL POTATO BLIGHT OF IRELAND, a caricature of O’Connell as a gross, lumpy potato, complete with organic Repeal Cap, reclining on a divan (xi., 1845, 256).

Keeping its readers focused on O’Connell’s holdings rather than the loss of the potato crop, The Times republished selections from Foster’s tirade against O’Connell on Christmas Day, 1845. The long descriptive passages along with some fresh material were printed as a sort of Christmas present to O’Connell and his followers.

The severe food shortage beginning to sweep through Ireland was marginalized by all this. The immediacy of the need for food was pushed into the background by the banter and politics of the metropolitan press. Foster continued to assert that poverty and mendicity were societal norms in Ireland. While he devoted many column inches recommending drainage and better husbandry, nothing in his writing pointed to the blight as a particular cause of distress. At the root of Ireland’s problems were indolent, ignorant Irish tenants and careless, rapacious Irish landlords, of whom Foster cited Daniel O’Connell as the premier example.

Although press opinion was still divided about the extent of the problem in Ireland, by the end of 1845 something of a consensus had emerged concerning public policy. While some papers expressed sympathy for the Irish peasantry, almost none of them suggested that English or government money (they were assumed to be the same) should be spent on Irish relief.There was a good deal of suspicion that such charity would be abused. More importantly, there was general agreement that the Irish landlords should shoulder whatever costs might arise. There was a strong sense that whatever the Union might be in theory, Ireland should support itself.

Figure 5.1: Punch, xi. (1845), 213.

The basic elements of future Whig government policy were, therefore, already prefigured in the British press by the end of 1845. There was one commonly-expressed assumption that partially mitigated an otherwise harsh attitude. Almost all of the newspapers assumed that if there was a famine in Ireland, Irish food would not leave the country’s ports. They also assumed, as a consequence, that the price of food in Britain, deprived of Irish exports, would rise. No one seems to have anticipated that food would continue to be exported from Ireland in the face of starvation.

Rather than disrupt the mechanisms of the corn market, which enabled merchants to realize good profits selling English and Irish grain to Europe, Peel made a secret contract with American dealers to import maize or Indian corn to hold as a reserve food. The Indian meal was to be stored in Irish warehouses to be released when necessary to hold down food prices. At the same time, Peel, contrary to his own best political interests, was moving towards repeal of the Corn Laws. He tried to keep his deliberations quiet. As a result, it seemed as though his Government was doing nothing about Ireland. In its 15 November issue, Punch ridiculed the Government in a satire in which Peel is made to announce, rather belatedly ‘I fear there is a failure of the potato crop.’ The Duke of Wellington, with Protectionist indifference, replies ‘Much exaggerated. Fellows in newspapers say anything. If a failure, what of it?’ Sir James Graham, Home Secretary, declares, ‘Hunger is only a vulgar habit – a wretched prejudice of the common people; nothing more.’ As a sly reference to the violence in rural Ireland, the Duke of Buccleuch is made to announce, ‘They say the gooseberry bushes are actually shooting,’ to which the Earl of Ripon replies, ‘Shouldn’t wonder.’ The illustration that accompanies the piece shows a gooseberry bush harbouring armed men (ix., 1845, 221). Regardless of the potato blight, Ireland was still good for a chuckle.

Notes

1. When it first appeared, many people did not recognize the potato blight as a disease new to Europe. See Bourke, 129-154.

2. generally opposed to the Corn Laws since 1839, but the paper’s proprietor did not like Peel or his idea of applying a sliding scale to the tariffs, which he had proposed in 1842; 2:172.

3. In stating that 2.3 million Irish people required charity each year, the Scotsman must have been including in its estimate the seasonal begging that took place among the cottiers.

4. The official history of The Times quotes a letter from a Peter Fraser, a militant Protestant, to John Walter, II, the paper’s owner, regarding the attack on O’Connell. ‘The Rascal’s done at last, I think, and in fact by you,’ Fraser wrote, and urged his friend to carry the attack on to the Papacy; 10; italics original.

5. For pictures and text dealing with Irish poverty appearing in the 12 August 1843 issue of the ILN, see Sinnema, 42-43.

6. Altick identifies Jeremy Diddler as ‘the archetypal moocher in James Kenney’s farce Raising the Wind…. (1803),’ 1997, 353.