Parsing Pharaoh’s Dream — July to December 1846

Peel’s willingness to commit a limited amount of state resources during the first half of 1846 had mitigated the worst effects of the food shortage in Ireland. He secretly acquired shipments of American maize, which were then stored in Ireland to be sold at or below cost in order to keep the price of grain from becoming exorbitant. At the same time his Government provided employment through public works.

With the fall of Peel’s administration at the end of June 1846, Lord John Russell and the Whigs came into power, supported, with guarded optimism, by O’Connell. He looked to the Whigs for the reforms he felt he could never get from Peel. John O’Connell, the Liberator’s son, wrote to The Times, triumphing in the defeat of Peel and his coercion bill. Delane’s leader writer responded with a starchy reprimand for the younger O’Connell and for all Irish politicians:

…[W]e believe that no Irishman, who is at the same time a professional politician, would give an invariably true and consistent account of his country’s condition…some fanciful will-o’-the-wisp — or some torturous prejudice — would indubitably lead him astray from the true conditions of the case, and plunge him over head and ears in the vagueness of impracticable speculation (The Times, 2 July 1846, 4).

As Ireland awaited the fateful potato harvest of 1846, the leading newspaper of the Empire could only repeat its long-standing charges that the Irish were overly imaginative, prejudiced and irrational. This was worse than calling them liars. Liars, at least, could recognize reality even while denying it; the Irish, apparently, could not.

As Russell formed his Government, he was confident that the Whigs could at last bring in reforms that would put Ireland on the road to peace and economic recovery. As Peter Gray points out, however, the new prime minister found he could not attract into government enough men who shared his old Foxite tradition of Whig reform (Gray, 1999, 147, 149). Neither could he find within his divided cabinet a balance between laissez-faire ideology and his stated desire for ‘justice for Ireland.’

By this time a consensus had emerged within Britain that called for a reconstruction of Ireland’s agricultural system and land-holding patterns. Many argued that Irish agriculture should more closely follow the English model. Moving against this tide, the Whig Morning Chronicle took the lead in publicizing alternative solutions. Even in May, before Peel’s defeat, the paper had published a letter to Russell from George Poulett Scrope, a radical MP, setting forth a proposal for peasant ownership of the land. Scrope cited the Prussian example of making landowners of the peasants who had formerly tilled the soil as serfs. He was convinced that

The Irish people must be fed from the resources of Ireland, and employed in providing those very resources from her fertile soil. The Irish landlords will not do this — cannot do it…. Then the State must step in, and compel them to do it or do it for them (Morning Chronicle, 4 May 1846).

Scrope had been developing the idea of peasant proprietorship for some time (Gray, 1999, 13-14). However, he knew that this was at best a long-term solution. In order to deal with the immediate crisis he urged Russell to extend relief to Ireland as a right, not as a possibility. The Irish Poor Law of 1838 had withheld this right, which had been granted to English paupers. Scrope, moreover, like most British commentators, insisted that the Irish landlords would have to bear the burden of an extended Poor Law. It seemed to make sense, at least in the metropolitan centre, to force the Irish landlords to either employ their tenants in improving drainage on their estates or to pay higher rates to support them in the workhouses. Unasked, much less unanswered, was the question of how the landlords could pay increased rates if their hungry tenants were not paying rents.

Although there was some interest in Scrope’s idea of a transfer of land to the Irish tenantry, his thoughts on the Poor Law attracted more attention. About the time that Peel resigned as Prime Minister, Delane printed in The Times a long letter from J. S. Trelawney, supporting Scrope’s proposal for an amended Irish Poor Law. However, Trelawney seemed less interested in feeding the poor than in improving their character. His letter extolled the good results that a proper English-style Poor Law would have upon the Irish. A poor law ‘having a severe test’ was necessary, Trelawney maintained, because ‘A poor law which relieves mere beggars who trade on mistaken benevolence is quite another thing.’ In Trelawney’s view,

The Character of the people [of Ireland] must be raised. They must be taught to require good food, good clothes and good houses, and not to sit over a bog fire in a pigsty, brooding over the chances of a good potato harvest, and seemingly careless of anything but the supply of the pressing necessity of the moment (The Times, 27 June 1846; italics added).

Trelawney’s metaphorical concept of teaching evokes images of a knowledgeable superior training an ignorant inferior within the contexts of teacher/pupil, parent/child, master/servant, or owner/animal relations. In addition, the phrase ‘taught to require’ shifted the condition of the Irish peasants from a struggle against the odds of survival to a simple challenge of will. The Irish had to will a better life for themselves, and, since they lacked the character to do this on their own, they would have to be taught, perhaps even forced to want self-improvement. They would learn to ‘require’ good things.

Framed in this way, Trelawney managed to substitute a question of character — the will to change — for the means whereby change could be effected. He suggested that the peasantry had it within their power to change, although, as his letter later made clear, this power would be imposed from the outside, via the Poor Law. The goal was to produce a rural society more like that of England. ‘With Poor Laws the county of Cavan would not long present the spectacle of 10,000 farms each under five acres; 12,000 of between 5 and 15; and near 2,000 of between 15 and 20…the cottier system would yield to that of large farms’ (The Times, 27 June 1846). Apparently it made no difference to Trelawney whether this ‘yield’ to large farms was the result of choice, of eviction or of the force of the Poor Law. Ireland’s small tenantry would be turned into agricultural labours as their subsistence-level farms were absorbed into large, high-farming operations necessary for growing grain or pasturing cattle.

Trelawney’s solution for Ireland’s more than two million cottiers, conacre farmers and small-holders was a direct cultural challenge to the Irish peasant’s way of life. Even as impoverished tenants, the Irish peasantry had an independence that the English agricultural labourer or factory worker did not enjoy. They were not at the beck and call of the ‘master.’ Although the Irish peasants no doubt preferred this independence, they in fact had little choice. Had they depended solely on hiring their labour to survive, many would have starved even in good times. The Irish press reported that Irish workers were clamouring for employment and finding none, a fact ignored by many English commentators.

Trelawney’s proposals also struck at another aspect of Irish peasant culture. He recognized that the poorest traditionally sought support from among their slightly better-off neighbors.

At present the poor are chiefly relieved by the poor. Probably in no country is this more the case than in Ireland. A more stringent Irish Poor Law would diminish this evil; because, once convince the people that mendicancy has no excuse, that unemployed labourers can obtain food by means of a [poor] law giving an indefeasible right to it, and begging would be proof of criminal indolence (The Times, 27 June 1846; italics added).

The Irish Catholic concept of charity as a means of grace was apparently alien to Trelawney, who saw begging as an ‘evil.’ He demanded the elimination of customs rooted in religion and in traditional concepts of hospitality. Trelawney’s recommendations were intentionally punitive and intended to correct what he and many English observers regarded as the shortcomings of the Irish character.

Trelawney was convinced that his English-style Poor Law would produce numerous societal blessings:

outrages would decrease; greater security would attract capital; greater capital would employ more labour; middlemen would give way to resident landlords…and the generally improved material conditions of a misgoverned and ill-advised society would afford leisure for the settlement of religious difference and for the consolidation of the union with the sister country (The Times, 27 June 1846).

An extended Poor Law was becoming a British panacea that promised to solve all of Ireland’s problems at minimal cost to the Treasury.

Russell was moving in this direction, but he had to deal with the immediate crisis. He proposed that the Treasury advance money to landowners through barony or county sessions to employ the destitute. These funds would be repaid in ten years at a rate of 3.5 percent. Continuing to some degree Peel’s use of public works, the Prime Minster proposed a grant of £50,000 to support work relief in the poorest districts. This was supposed to have enabled the poor to feed themselves strictly through their own labour. Russell did not intend to revert to Peel’s occasional distribution of free corn meal, however. He was reported in Punch to have claimed that, ‘As evil had risen from interference by the Government with the supply of the public food, he did not propose to interfere with the regular mode by which Indian corn and other kinds of grain might be brought into the country.’1

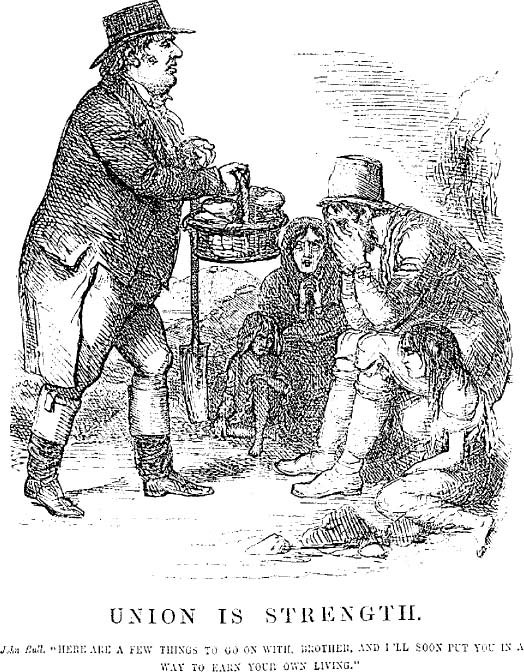

The Government’s £50,000 grant was too limited in size and scope to make a serious impact upon the growing hunger in Ireland. Nevertheless, in the 17 October 1846 issue of Punch celebrated England’s image of itself as Ireland’s benefactor (while at the same time taking a dig at Repeal) in Richard Doyle’s cartoon titled, ‘UNION IS STRENGTH’ (Figure 7.1). The corpulent figure of John Bull bends down to a seated, desolate and starving Irishman and his family, saying, ‘Here are a few things to go on with, brother, and I’ll soon put you in a way to earn your own living.’ And with that, John Bull hands the Irishman a basketful of bread and a spade. The bread, of course, was the English agricultural worker’s staple diet to which the Irish were to be converted. Grain cultivation in England supposedly produced an abundant food supply, but it required a plough, not a spade. The spade in Doyle’s cartoon represents the work that the Irishman would undertake ‘to earn his own living’ as a day labourer. He would no longer be an independent subsistence-level farmer on his small plot of rented land. This was a spade for digging the landlord’s drainage ditches, not for cultivating the tenant’s potato ground.

Figure 7.1: Punch, xi. (1846), 161.

In spite of the blackening potato fields, the Whig Government closed down the public works at the end of the summer of 1846 so that these projects would not draw labourers away from private harvests of the landlords’ grain. The closing of the public works was certainly not for a lack of funds on the part of the Government. On 20 July The Times published ‘the Net Public Income of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the Year.‘ This indicated that the Exchequer advanced 1,750,288l2s 1d. ‘for Local Works, &c., under various acts of Parliament,’ while still showing an ‘Excess of Income over Expenditure,’ a government budget surplus of 2,820,472l 13s 6d. The United Kingdom, as a whole, was recovering from the financial difficulties of the early forties.

The 1846 grain harvest in wheat, barley and oats, while a very good one, did not suddenly provide work and wages for all of those Irish who, having no food, needed employment in the wage economy in order to survive. The member of Parliament from Mayo, Mr. Browne, denied Lord Russell’s earlier statement that there was sufficient ‘work and wages to support the population’ in Ireland. As reported in The Times on 26 August, Browne stated ‘that the employment rising from the harvest in Mayo, and, indeed, in Ireland generally, was perfectly inadequate’ to employ all those who needed work to compensate for the loss of the potato crop.

The Whig Government’s attraction to laissez faire paralleled O’Connell’s attachment to the rhetoric of Repeal. At the beginning of July, the Earl of Miltown had called upon Daniel O’Connell to suspend Repeal agitation for a year to give the Whigs time to consolidate their new Government. The Times chose to interpret O’Connell’s refusal as a sign that he feared losing the income he derived from the Repeal Rent. ‘Why, then close the doors of Conciliation hall,’ the paper asked satirically, ‘or deprive its treasury of the weekly rent, (the “sacred fund”), be the contributions ever so trifling? The sheer folly of adopting such a course of policy could only be compared to the killing of the goose that laid the golden eggs’ (18 July 1846).

A fall off in Repeal Rent was not the main problem worrying the aging Liberator, however. A split occurred in his organization when the Young Irelanders abandoned the Repeal Association. They were frustrated with O’Connell’s insistence upon ‘moral force,’ in spite of his inability to get the Whig Government to respond adequately to the Famine. Punch, of course, now enjoyed a new opportunity to ridicule O’Connell, this time over his inability to control William Smith O’Brien and the Young Ireland movement. In the 22 August 1846 issue, Richard Doyle depicted this division in a drawing titled “‘A GENTLEMAN IN DIFFICULTIES;“ OR DAN AND HIS “FORCES,“’ (Figure 7.2). Here the fat old sow of Moral Force is easily driven by farmer O’Connell, while the Young Ireland shoat of Physical Force, though tied by its hind leg, wants to go off in its own direction. The cartoon is particularly clever in satirizing the Liberator’s support of the Whigs. According to the signpost in the background, it is the shoat, ‘Physical Force’ that strives in the direction of Repeal, while the old sow, ‘Moral Force,’ trots down the road toward ‘Whiggery’ (spelled backwards on the sign).

The Young Irelanders formed their own organization, the Irish Confederation. Punch produced a savage attack on the group in a Leech cartoon depicting a monkey-faced William Smith O’Brien in a Repeal cap selling bullets, blunderbusses and pistols to an equally simian-looking Paddy. ‘YOUNG IRELAND IN BUSINESS FOR HIMSELF’ also showed pikes and scythes as part of the stock in trade (Punch, xi., 78). The antiquated firearms and primitive agricultural weapons suggested the inadequacy of nationalist military resources and the foolishness of the idea that Ireland could overthrow England by arms. A sign reading ‘Pretty little pistols for pretty little children’ suggested, as did Leech’s earlier cartoon on the Coercion Bill, that the Irish were childlike and therefore irresponsible, clearly unable to manage their own nation.2

Leech’s last ‘big cut’ on O’Connell in the autumn of 1846 was entitled ‘FAMILY JARS AT CONCILIATION HALL’ (Punch, xi., 119). The artist depicts Smith O’Brien and O’Connell as an embattled husband and wife. O’Connell, presented as a slatternly wife wearing a Repeal cap, pushes shut the door ironically labeled ‘Conciliation Hall’ (the meeting room of the Repeal Association), on a dangerous-looking Smith O’Brien, who is armed with a shillelagh labeled ‘Physical Force.’ Mr. Punch and several English political leaders peer in delightedly through the window. The word ‘jars’ in the cartoon’s title might connote drinking, as well as ‘jarring’ or conflicting behavior. The broken dishes spilling from the cupboard with which O’Connell barricades the door suggest the chaos that physical force might cause if it got into Irish politics.

Figure 7.2: Punch, xi. (1846), 69.

None of this addressed the issue of the long-awaited potato crop. Based on previous experience, there seemed no particular reason to expect a second failure. However, in 1846 the blight did not wait until digging time to announce its presence. On plot after plot the plants suddenly turned black. With his Government barely in office, Lord John Russell expressed his regret to the House for having to announce ‘that although there were at present, in the greater part of the counties of Ireland…work and wages sufficient for the support of the… population, the prospect of the potato-crop was this year even more distressing that it was during the last’ (The Times, 18 July 1846).

On 18 July, in the same issue of The Times that carried the Prime Minister’s speech, the paper published a note from an Irish correspondent under the optimistic title, ‘THE NEW POTATO:’

The accounts to-day from Limerick, Galway and Mayo, are extremely unfavourable, as showing beyond all doubt that the taint of last year has made its reappearance in the new crop. The fact has created great alarm in those districts, and the demand for supplies of Indian meal promises to be very extensive.

Yet, even in reporting on the weather in Ireland, The Times seemed hesitant in raising the possibility of a disaster. On 30 July, The Times correspondent in Dublin wrote apologetically, ‘Without wishing to raise any unnecessary alarm, I regret to say that the state of the weather for the last week, and at just the most critical juncture of the season, has been such as to raise the greatest apprehensions for the safety of the newly ripened harvest.’ To most English readers, ‘harvest’ meant the grain harvest. The report continued, describing the heavy rains that had flooded the countryside around Dublin, leaving ‘vast quantities of corn…lying prostrate in all directions.’ Only then did the writer consider the food upon which millions of Irish depended: ‘…of the potato, the accounts continue most unsatisfactory, and even making due allowance for exaggerated alarms, there seems to be no reasonable doubt that the deficiency, if it do [sic] not exceed, will at least equal that of last year’ (30 July 1846; italics added). Apparently the writer felt that only by discounting Hibernian exaggeration could he suggest the potential seriousness of the situation to his English readers.

Unfortunately, the ‘deficiency’ of potatoes turned out to be massive. Most of the 1846 crop was destroyed. From a normal yield of six tons of of potatoes per acre, the fall harvest had produced on average only between one and one-and-a-half tons. Many of the poorest families had eaten their seed potatoes in spring. This, along with the general disruption of agricultural life among the tenantry, meant that potato acreage had fallen by around twenty percent. In the words of James S. Donnelly, Jr., ‘to use the adjectives “total” and “universal” in reference to the failure of 1846 is to exaggerate hardly at all’ (J. S. Donnelly, Jr., 2001,57-58).

Nevertheless, politics continued to shape the reporting on Ireland in the British journals. The leading item for the ‘Ireland’ column in The Times of 10 August, for example, concerned the visit to Cork city by the new Viceroy, the Earl of Bessborough.3 The Times published the city council’s address to Bessborough, but was annoyed that this Repeal-dominated body proffered ‘more of advice than congratulations.’ The address pointedly voiced admiration for Peel’s late program of ‘perfect civil and political equality with the sister kingdom.’ It called for ‘employment for the labouring class as the only mode for removing the destitution and misery, in which 2,000,000 of Irishmen, our fellow-subjects, are involved.’ The Cork councilors requested an increased parliamentary franchise and an obliteration of ‘all remnant of that religious ascendancy, which a state establishment for the church of the minority engenders and sustains.’ Finally, the council called for Repeal by asking Bessborough to ‘encourage the material and intellectual improvement of the people so as to fit them for that legislative control over their own affairs.’ Not shy about its politics, the council reminded the new Viceroy of the old independent Irish parliament, ‘which your noble family once witnessed with so much pride…under the mild and paternal sway of our beloved Sovereign’ (The Times, 10 August 1846).

Perhaps as an immediate counter to the Cork Council’s nationalist cheek, the next item in The Times ‘Ireland’ column was a piece on the ‘PROJECTED ORANGE DEMONSTRATION.’ The Orangemen of Enniskillen were planning a ‘demonstration of physical force,’ presumably to be directed at their Catholic neighbors, to protect and defend the very Ascendancy that Cork was hoping Bessborough would render obsolete.

Finally, the third Irish item of the day concerned the failure of the potato crop. The Times correspondent simply stated that ‘There is no improvement in the reports received to-day — north, south and west, all are alike.’ Delane’s writer then focused on a report from the presumably more trustworthy north. The Erne Packet of Fermanagh stated that ‘the present state of the [potato] crop justifies the very worst forebodings.’ From the south there were reports of cows and sheep being stolen in Glandore and of a riot at Ballydehob, ‘where the unfortunate people took the bread from the bakers’ shops, and made use of it’ (The Times, 10 August 1846). Still, The Times refused to be panicked. A month later similar accounts of unrest in Clare, Limerick, Roscommon and Fermanagh were glossed over by The Times correspondent as ‘having their origin more in the apprehension of scarcity than in the positive existence of distress itself’ (The Times, 10 September 1846).

Yet, the same issue carried a reprint from the Clare Journal that began with the statement: ‘The fearful calamity which has at present befallen the country seems to have been the cause of these outrages.’ The journal quoted a correspondent who stated that around Newmarket

The harvest is all in; the people are idle; the potatoes are gone, and I fear the ruffianly part of the community only wait an opportunity of committing depredations. They are in a wretched state of misery, almost starving; and if something be not done quickly the consequences will be very bad (quoted in The Times, 10 September 1846).

What may have attracted Delane’s attention to this piece was the Clare Journal’s contention that those who broke the law ‘with such an awful visitation of Heaven staring them in the face’ were committing acts ‘calculated to draw down Divine vengeance on the land,’ all of which suggested a redundancy of retribution. Nevertheless, while the view from the periphery saw that a second year of scarcity was causing deep unrest, the metropolitan centre preferred to normalize the discontent as ‘ordinary.’ The Times still seemed anxious to play down any excuse that might result in unwise and expensive reactions from the Government.

Perhaps more to Delane’s liking was another reprint from Ireland, again from the Erne Packet of 7 September, carrying a warning from Lord Lorton:

…upon the first appearance of riot and disturbance, an immense body of soldiers would be spread over the land in a few days, poured in from England, &c.; and then, indeed, the horrors of war and desolation would commence, which none of the most humane landlords, however anxious they might be, would be able to control…. I recommend that no attempt should be made toward the breaking of the peace by the collection of large meetings, which (to say nothing of the above matters) would most fatally interfere with all harvest work (The Times, 10 September 1846).

Also on the same day, The Times attacked Lord George Bentinck, who was quoted as urging the Irish ‘to avail themselves of their own superabundance of grain and keep it at home….’ As the leader of the Tory protectionist wing in the House of Commons, Bentinck continued to oppose free trade. He believed that it was the government’s duty to regulate the trade of grain. In the face of a second widespread potato crop failure, which he recognized as a situation well beyond the usual levels of scarcity, Bentinck wanted the Government to restrict food exports from Ireland. The Times’ lead writer responded with great sarcasm, arguing that Bentinck’s position

is only too obvious and familiar. The Irish have already adopted it without waiting for illumination from Chelmsford [Bentinck’s seat]. They are keeping their grain at home. Tenants are refusing to pay their rents. Labourers are stopping the corn on its way to market-towns and corn mills. Others are taking bread out of the bakers’ shops. Landlords are demanding that Parliament should feed and employ the people with a grant equivalent to their own rents, which they find difficult to obtain….

From the perspective of Delane’s lead writer, the whole of Ireland seemed to have turned to begging. ‘This process, which we should call national bankruptcy, or national mendicancy, or national rascality, or something of that sort, Lord GEORGE BENTINCK calls “clinging to the last plank of protection’” (The Times, 10 September 1846, 3).

The editorial greatly exaggerated the ability of the Irish poor to resist the export of grain from their country. The permanent presence of the British army in Ireland insured that there were ample military escorts available to accompany grain shipments to the ports. Nevertheless, The Times, without any evidence, insisted that ‘the repeal of the Corn Laws, so far from having caused the present famine in Ireland, has considerably mitigated it…. There is more food and more employment’ (10 September 1846, 3).4

To the extent that The Times backed any response to the crisis in Ireland in 1846, the paper continued to push for an extension of the Irish Poor Law that would break with the workhouse regime and provide outdoor relief. The Morning Chronicle, on the other hand, continued to open its pages and editorials to more imaginative solutions. In early October the Chronicle began publishing a long series of articles written by economist and political theorist John Stuart Mill. Running until January of 1847, Mill’s articles contained around 50,000 words on Ireland’s problems. He believed that he had the only approach that combined, as he later wrote, ‘relief to immediate destitution with permanent improvement of the social and economical condition of the Irish people.’ In other words, Mill, like other English observers, saw the Famine as an opportunity to create a new Ireland. He saw the ruined island, as he later wrote in the Examiner, as a ‘tabula rasa, on which we might have inscribed what we pleased’ (Kinzer, 44, 47-48).

Mill rejected outdoor relief, arguing that any extension of the Poor Law would make the Irish even more dependent upon English charity without changing the economic basis of the country. He noted that while competition in England had made wages lower, competition for land in Ireland made rents higher. Rents were so impossibly high that the tenant was constantly indebted to the landlord, who held the land, not as a hereditary right, but as property seized from its original owners. Mill, moreover, maintained that, as Ireland had been controlled by the English for five hundred years, the present state of the country was entirely the result of their misrule (Morning Chronicle, 7 November 1846, 4).

Mill pointed out that the Irish peasant’s intense efforts to reclaim small tracts of wasteland refuted charges that Irish laziness was an inherent trait. Mill, like Scrope, went against the grain of conventional thinking in Britain, which held that small-scale farming was inefficient and that peasant proprietors would lack motivation for improvement. Mill was certain that the Irish would work hard on their own land, and would eventually limit the size of their families (Kinzer, 53, 55). He made a powerful argument for a form of fixity of tenure combined with fair rents. Once confident of the continued occupancy of their holdings, Mill believed that the peasants would then invest in the improvement of the land. Yet, he knew that Parliament could not be convinced to pass such radical legislation (Kinzer, 62). Therefore, he suggested that with government support 200,000 families could be settled on wasteland, which they could then reclaim. While Scrope had introduced a wasteland settlement bill in Parliament back in April, Mill made a more powerful theoretical argument in favor of the scheme (Kinzer, 68).5

Like many social theorists of the day Mill placed great emphasis upon the role of ‘character.’ He was convinced that the worst aspect of the ‘cottier system’ in Ireland was its corrosive effects upon the character of the peasants, sapping industry and eroding prudence (Kinzer, 61). Unfortunately, such language too easily called up the stereotype of the feckless Irish, even as he argued that they could rise above it. Mill insisted that his solution would convert ‘an indolent and reckless into a laborious, provident and careful people’ (Morning Chronicle, 14 November 1846, 4). Nevertheless, he still saw limitations in the Irish peasant’s character. He opposed schemes for government-assisted emigration, not only because of the cost, but because the Irish peasant allegedly lacked the individualism necessary to succeed abroad.6

Mill believed that his scheme was infinitely preferable to the anglicization of Irish agriculture. As he accurately noted,

The introduction of English farming is another word for the clearing system. It must begin by ejecting the peasantry of a tract of country from the land they occupy, and handing it over en bloc to a capitalist farmer. The number of those whom he would require to retain as labourers would be far short of the number he displaced (Morning Chronicle, 14 November 1846, 4).

Mill’s ideas met with some interest. As Bruce L. Kinzer notes, however, while reclamation of wasteland was not a new idea, the concept of peasant proprietorship was very radical. Nevertheless, for a time Russell, with Bessborough’s support, attempted to push for some sort of reclamation bill, but like most of the Prime Minister’s well-intentioned initiatives, it failed to garner support (Kinzer, 72-73, 79).

Russell was thrown back on his belief that the Irish landlords would behave like (idealized) English landowners and employ their starving tenants for a subsistence wage. He later acknowledged his disappointment in a letter to the Duke of Leinster, quoted in the leading article for The Times on 10 November: ‘It had been our hope and expectation that the landed proprietors would have commenced works of drainage, and other improvements on their own account, thus employing the people on their own estates.’ Russell complained, however, that the Irish landlords would not employ their own tenants. As a result, ‘the Legislature had been driven to measures of relief likely to waste a vast capital in comparatively unproductive labour’ (The Times, 10 November 1846). In contrast to the irresponsible behavior of the Irish landlords, The Times asserted: ‘we in England consider it the first duty of the landlord to provide extraordinary employment to meet extraordinary distress’ (The Times, 10 November 1846).England had not, of course, faced such an extraordinary disaster in living memory.

Irish landlords insisted that they could not afford to undertake the role that the government and the newspapers expected of them. On 10 November The Times unsympathetically reviewed Lord Desart’s protest that his own circumstances did not permit him to hire a significant number of workers. His excuses were: he was only a tenant for life; he could not get assistance under the Drainage Act; he could not obtain a private loan; and if he employed the poor at his own expense, he would have to pay a general baronial tax. None of the legislative support for employment was available to him, he claimed. Payment from his own pocket was also impossible, because his estate was encumbered. On 10 December, the Marquis of Conyngham, who had been pilloried by Thomas Campbell Foster the previous year, wrote to The Times to say:

My attention having been drawn to a letter addressed to you by my solicitor, Mr. Benbow, in reply to some strictures of yours upon the lamentable state of my property in the county of Donegal. I beg to say that all his statements are quite correct; but he has omitted to mention that my estates are heavily encumbered, and that it is totally out of my power to make the outlay required for the improvement of the property…a state of things which I deeply deplore, but have no power to remedy (The Times, 10 December 1846).

Such statements could not have helped to improve the status of the Irish landlords in English eyes.

Nevertheless, since the onset of the blight in 1845, many landlords had not received their rents, and by the end of 1846 the number facing insolvency was growing. The Irish landlords, as a class, were simply not prepared to finance the necessary transition to lead the peasantry into a cash economy. Landlords, short on cash themselves, held to the tradition of collecting rent in kind – cattle, pigs or grain. Paying tenants as day labourers was a radical challenge to the landlords’ cash flow.

As the year ended, the British press recognized that Ireland was facing a crisis, yet the Famine was not the only issue that constituted the news from that country. The 12 December issue of the Illustrated London News carried a series of brief reports under the heading. ‘Ireland. Lamentable Condition of the Country.’ These began, not with news of famine, but with an item that may have provided more excitement for the English reader — an account of the increasing arms sales in Tyrone and Tipperary. According to the ILN, O’Connell himself alluded to the purchase of arms, but placed it within the broader context of the desperation felt by many Irish peasants. The Liberator is quoted as saying:

…famine, pestilence, and death were raging among the people, and there was a most sullen state of discontent in the land. The people were…buying arms and wanting food. On all sides the father was starving, the mother mourning, and the children wailing…It was a horrible picture to look at — it was a frightful thing to think of…. The Government had not the means of meeting the emergency…. They unfortunately allowed themselves to be deceived by flatterers into the belief that the failure of the potato crop was not general. It was now too late — and it would require three times the amount of food in the country to support the people (ix., 12 December 1846,37).

There was other news from Ireland. The Illustrated London News also reported on ‘The Repeal Association,’ ‘Serious Fire in King’s County,’ and ‘Loss of Three Lives from Carbonic Acid,’ followed, finally, by extracts from Irish papers reporting on the effects of the Famine. These items appeared under the headings ‘More Deaths from Destitution,’ ‘Reported Disturbance in Kilkenny,’ and ‘Outrages by Armed Parties.’ The news from Ireland concluded with ‘Another Frightful Murder’ followed by two more murder items. From the vantage point of Frederick Bayley’s London, death from starvation was just one in nine topics of interest coming from Ireland.

The Illustrated London News’ ‘More Deaths from Destitution’ reprinted an item from the Cork Constitution concerning the death of an unpaid labourer named Connor at Skibbereen in County Cork, one of the worst-hit famine areas. The injustice of Connor’s death was noted in that he died while still employed, with ‘nine day’s wages for labour performed on the public roads being due to him (37).’ This documented one of the problems of shifting the Irish peasantry to a cash economy: the public works system was slow to pay the small wages its workers earned (37).

The following item reprinted from the Galway Mercury named two men, Carter and Davin, who died ‘having been unable to procure food or employment.’ As the report makes clear, these unfortunate victims were no paupers hanging on the rates, but rather men who were working or searching for work. Additionally, in Galway ‘several men, women and children [perished] of diseases brought on by misery and destitution’ (37). In this case, there is a shift from giving the names of individuals and their exact circumstances of death to references to anonymous persons dying from unnamed diseases. As the numbers of the dead grew, this anonymity would prevail, and the individual’s death became sunk in the mass grave of editorial brevity.

At the very end of 1846, the Observer published in a single issue several contrasting articles and letters related to the Irish crisis. A letter from Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, discussed the loan of one million pounds that the Government hoped would encourage Irish landlords to hire destitute tenants. Trevelyan’s letter carried the proviso that ‘the proprietors of an entailed estate’ could sell their property for the ‘purpose of repaying the advancements for improvement,’ or the Government would sell their estates in cases of ‘default of payment of two consecutive installments.‘ Of course, all landowners were expected to repay the loans with ‘the contribution on the part of the occupier being in the shape of increased rent to the proprietor’ (Observer, 28 December 1846,3c).

Adjacent to Trevelyan’s letter, the Observer quoted Daniel O’Connell to the effect that Irish landlords would have to give ‘a whole year’s income’ to famine relief, more or less by default, since ‘the tenantry had not the means of paying the rents.‘ In an address to a national famine relief committee that he had organized, O’Connell called for a much larger loan than Trevelyan had described. The aging Liberator demanded an immediate government loan of £20,000,000. The precedent for such a large Treasury expenditure was the £20,000,000 spent to compensate slave owners for their loss of property when slavery was abolished in the British islands in the Caribbean.

O’Connell also called for a new organization to collect subscriptions for famine relief. According to the report, he wanted ‘a central committee for all Ireland to assemble in Dublin, and he could not help observing that if such a committee [in the form of an Irish Parliament] had been sitting here for the last 46 years, Ireland would not be in her present deplorable condition (cheers).’ O’Connell accurately estimated that ‘fully three millions of people must be fed until August next. Any subscriptions [from private charity] that could be raised would be but as a flea bite. Never was the country brought to such a state of destitution.’ He concluded his remarks by repeating his belief that ‘the real cause of the dreadful distress of the country [was] the want of a local legislation (cheers). What was to save Ireland next year? Nothing but the management of their own affairs by Irishmen (cheers)’ (Observer, 28 December 1846, 3d). As the situation in Ireland grew more desperate, there was no cessation of politics on either side of the Irish Sea.

In the same issue of 28 December, the Observer ran an article praising the English Christmas Dinner Clubs and their contribution to the improvement in the quality of geese for the Christmas dinner. In an adjacent column, the editor placed a letter from ‘A medical gentleman,’ who proposed replacing the maize being sent to Ireland with biscuits and herring, ‘such being so cheap at the present time.’ It seemed reasonable to the writer that the large supplies of the Navy’s ‘stale store biscuits’ should be immediately sent to Ireland’s distressed districts. The juxtaposition of the two articles provided, by implication, the Observer’s editorial comment on the differences between Ireland and England at the Yuletide season.

A few weeks earlier the Illustrated London News had made a more pointed contrast between the two islands in its report on the Smithfield Club Cattle Show in Baker Street, London. Intended, perhaps, as propaganda for the anglicization of Irish agriculture, the front-page story contrasted the wealth of rural England with conditions in County Tipperary, Ireland: ‘In one place, there is a deficiency of food; in the other, a superabundance of it; here, we have the fat kine of Pharaoh’s dream; there, the leanness of actual famine. It is not to scold that we notice the difference between place and place, or to extract from it a great social wrong.’ Referring to the exhibitors at the Show, the ILN insisted: ‘If the Royal and noble competitors had never expended an ounce of oil cake on their stock, the relative conditions of the two countries would have been much the same’ (ix., 12 December 1846,36). Famine in Ireland was again normalized as simply another example of the laxity and incompetence of the Irish.

Once the almost complete failure of the 1846 potato crop was accepted, the Government reluctantly reopened the public works as winter approached. The fact that such relief measures, no matter how inefficient, might save lives did not seem to lighten the gravity of this ideological backsliding. Facing a harsh winter of hunger, the Irish peasantry was at the mercy of a governing elite that begrudged the capital spent on Irish relief and that searched anxiously for a permanent solution to Irish need. In the meantime, throughout the winter of 1846-1847, the deaths from starvation and disease rose sharply. Ireland was now in the grip of famine.

Notes:

1. Punch, ‘Political Summary,’ Introduction to volume xi., July to December, 1846, no page number; italics added

2. Altick points out that the arrangement of antiquated arms in the cartoon suggested the display of old weaponry in the Tower of London. He identifies the figure behind the counter as William Smith O’Brien; 1997, 257–58.

3. The Russell Government, having first appointed the unknowledgeable Earl of Lincoln as Secretary to Ireland, made the canny appointment of Bessborough as Lord Lieutenant. As an Irish landowner himself, it was hoped that Bessborough would provide some understanding of and leadership for the country. He was also on good terms with O’Connell

4. There was more food available but not at affordable prices. Kinealy states that instead of declining by the end of the 1846 the price of maize had risen to 3s per stone in some areas; 93. As the markets expanded, however; the price of grain in Ireland eventually did drop by the autumn of 1847; 201.

5. Although Mill was very much aware of trends towards peasant-ownership of land on the Continent, he had worked as an administrator in India House, and was influenced by land policies in India, a subject about which his father, James Mill, had written. For influences on Mill’s thinking on this subject, see Kinzer, 55-59.

6. Kinzer points out that Mill’s views on the Irish character were typical of his times. He also suggests, however, that Mill was so convinced that England bore the responsibility for Ireland’s condition, that it would have been wrong to try to shed its Irish problem abroad through assisted emigration; 65.