The Uprising at Boulagh — 1848

In 1848 the Illustrated London News acquired a new editor when Charles Mackay replaced Frederick Bayley. Mackay appears to have been less sympathetic, or at least less sentimental, regarding Ireland. A Scotsman, Mackay had been a writer for the Whig Morning Chronicle and in the early forties returned to Glasgow to edit the Glasgow Argus (Griffiths, 1992, 391). In taking up the editorship of the ILN, he brought a more Whiggish bias to its editorial policy. Eventually, Mackay was to publish some critical accounts of the Government’s handling of the Famine, as well as some memorable illustrations of the conditions of the peasantry. At the outset, however, his empathy for the Irish was not particularly evident.

Each spring Frederick Bayley had commemorated St. Patrick’s Day with a poem and an illustration that often included Irish folk customs. Mackay made no room for such sentimentality in March 1848. The Illustrated London News’ issue of 4 March contained a special supplement on the French revolt against Louis Phillipe. The paper was filled with disturbing wood engravings of peasants in the Royal Palace. Mackay continued to follow the tumultuous events in Europe with pictures of popular risings in Germany, Naples and Poland. Such scenes were not presented as merely foreign news, however. Watching the overthrow of European monarchies, the ILN became increasingly wary of what it took to be the Irish enthusiasm for joining nationalistic associations and for forging pikes. Unlike Frederick Bayley, Charles Mackay seemed to harbour an apparent distrust of the Irish as incipient revolutionaries. In mid-March the ILN, commenting on a recent meeting of the Repeal Association, noted ‘that the French Revolution is beginning to operate on the public mind in Ireland…’ (xii., 11 March 1848, 164).

It was not until the 25 March issue that Mackay belatedly recognized St. Patrick’s Day. Whereas Bayley had published sentimental illustrations symbolizing the Irish nation, Mackay was satisfied with an illustration of the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations at Dublin Castle. The guests were not peasants or even middle-class celebrants. Instead, the illustration of the ball depicted the other Ireland, that of wealth, power and status. Beautiful women in very fashionable dresses and tall men with high collars, or officers dressed in elaborate military uniforms with plumed hats, wander by flowing fountains and bowers hung with caged birds (192). The elegance and implicit wealth suggested that, whatever threats from France reverberated in Ireland, the ruling class was in control.

By the end of May, the Illustrated London News’ new editor seemed to have lost all patience with Ireland. The leader on the front page of the 27 May issue (appearing above a dramatic illustration of ‘the Grand National Fête in Paris’) featured a denunciation of the Irish peasantry. Mackay’s writer began by admitting that the English did not understand the Irish. The fault lay with the ‘unmanageable’ Irish, however, and, in language reminiscent of Thomas Campbell Foster, the ILN resorted to the travel writers‘ comparisons of the Irish with tribal ‘savages.’

So much has been said and written about Ireland — so many and so conflicting have been the statements put forth, that the people of this country [England] begin to loath the very name of Irish misery. They would relieve it if they knew how; but the task seems too great for their accomplishment or for their comprehension. They sometimes believe the Irish peasant to be unteachable…. The peasant does his best to live. He offers an enormous rental for a potato-patch without calculating whether he can afford to pay it or not. Potatoes are all his diet…. He lives in a wigwam, and shares it with a pig. He speaks a barbarous language, and is in arrears with the intelligence of the world…. The masses of the people cannot be called civilized by any stretch of flattery…. [T]he condition of the Esquimaux or Kaffirs is preferable to theirs…. The Laplander can get rein-deer meat or blubber to supply his need, but there is nothing but the potato, and not enough of that for the Celt in Ireland…. Rent absorbs everything but the potato. All the other produce is exported to England to pay it. When the potato fails, the peasant has but to resign himself to starvation, to fever, and to death. When it is ordinarily abundant, a perilous fecundity among the people lays up a stock of embarrassment for future years (xii., 27 May 1848, 335-36).

This passage represents a summation of British frustration, as well as the confusion of attitudes, regarding Ireland and the Irish. Although the writer implied that the Irish worked hard, they, not their landlords, were somehow to blame for the outrageous rents they had to pay. Moreover, the fact that they paid them and had managed to survive seems to have been taken as evidence of a basically savage condition, similar to that of other exotic and inferior peoples of the world. Such sentiments paralleled the colonizer’s fascination with and abhorrence of those natives in the colonies, who, in spite of their incomprehensible ways, somehow managed to send taxes, food and raw materials to the motherland.

Mackay’s leader capped this tirade with a statement that echoed basic Whig policy regarding Ireland: ‘We can, in fact, see no hope for Ireland until the people are raised into the condition of bread-eaters.’ However, unlike Trevelyan, the Illustrated London News called for the Irish peasants to invoke squatters’ rights over the bogs and wastelands of Ireland, thus opening up unused land for grain cultivation (336). This rather radical measure suggests that Mackay would not travel in lockstep with Russell’s Government.

The Times had long expressed something of the same fatalism with regard to Ireland and the repetitive nature of its problems. John Delane published a leading article in the 11 July issue of The Times written in the voice of a bored clubman, wearyingly restating the obvious:

There is a hopelessness about all Irish legislation which is almost instinctive. For every other part of the empire we plan with ardour, because we plan with hope…. But in Ireland it is not so. There, plan succeeds plan, scheme follows scheme, and legislation repeats itself, only to prove the difficulties of the task and the futility of our endeavours (5).

The leader writer acknowledged that ‘Ireland is part and parcel of ourselves.’ Yet, he also pointed out how very different conditions in Ireland were compared to Britain. Ireland ‘is supremely wretched…. It is a complication of misery. It is difficult to say which is the worse off — the peasant whom a competing poverty drives to…starvation, or the lord of a soil which demands for itself more than it can yield to him.’ By any standard it should have been obvious who was worse off. Increasingly, however, the negative assessment of Ireland included peasant and proprietor, both, in British eyes, locked in an embrace of futility, debt and poverty.

For want of…an affluent resident proprietor…the ill-starred peasantry pass from one stage of privation to another. There is no employment for them, no charity. The bogs remain undrained, the wastes unreclaimed…. Land, to feed the population aright, must in many instances change hands…. Until a wealthy has superseded a poor proprietary, and capital with enterprise succeeded to a rack-rent indolence, the people of Ireland will go on starving on potatoes, dying of famine, and shooting the few landlords who venture to reside on their mis-called properties (The Times, 11 July 1848, 5).

Parliament did eventually pass an encumbered estates act in 1848. Intended to make it easier to sell off heavily indebted properties, the act had little effect.

Meanwhile, some observers were beginning to discern a ‘social revolution’ taking place in Ireland. For many Irish people Britain, America and even Australia seemed their only hope. Emigration became the solution for those who could raise the money for tickets and sea stores. By the winter of 1847-48, however, the status of those emigrating was changing, as reported in the pages of the Meath Herald and reprinted in the Illustrated London News:

Numbers of small farmers, holders of twenty acres and under…have already commenced to make preparations for the spring emigration…. [T]he spirit of emigration…is no longer confined to the struggling farmer or the bankrupt tradesman — there are numbers occupying a most respectable position in society…who now begin to cherish the prospect of doing more in America or the colonies than they can ever hope to accomplish at home. This spirit…will prove highly detrimental to the country… (quoted in the Illustrated London News, xii., 22 January 1848, 33).

For some of those who could not afford voluntary emigration, transportation for criminal offenses represented a desperate alternative. Those with no options laid down and died. The Scotsman reprinted from The Times the verdict of a coroner’s jury in Galway at the end of January. The jury members rebelled against Government policy. At the inquest on the death of a ‘travelling beggar named Mary Commins,’ the jury returned the following verdict:

We find that the deceased, Mary Commins, died from the effects of starvation and destitution, caused by a want of the common necessities of life …Lord John Russell, the head of her Majesty’s Government, has combined with Sir Randolph Routh [chairman of the Relief Commission] to starve the Irish people…we find that the said Lord John Russell and the said Sir Randolph Routh are guilty of the wilful murder of the said Mary Commins (Scotsman, 27 January 1848, 2; italics original).

The item concludes with a notice that the judge finally persuaded the jurists to give a more ‘sensible’ verdict.

If citizens chosen from the jury list could give vent to such sentiments, how stable was the country as a whole? The year of 1848 saw revolutions spreading throughout Europe, all of them reported by the British press with a mixture of outrage, fascination and fear — fear that Ireland would seek to escape the empire by ‘physical force.’ Punch began its glance back over the first half of 1848 with a simple statement:

Few matters of importance affecting English interests occupied the attention of the Parliament during the remainder of the Session…[than] the state of affairs in Ireland and France. The French Revolution …stimulated the disaffected in Ireland to open rebellion, and districts were proclaimed to be under the operation of the prevention of Crime and Outrage Act….1

In mid-summer, the attention of the British press turned increasingly to nationalist activities within Irish communities at home and abroad. The Manchester Guardian complained that nationalist supporters of John Mitchell, founder of The United Irishman, were misleading the expatriate Irish inAmerica: ‘…knowing the gullibility of poor Paddy they are cramming him full — choking him in fact—with “sympathy for Ireland….”’ ‘Perhaps,’ the writer concluded, ‘we may have a partial rising in Ireland.’ Given the military superiority of the British army, the Guardian’s leader writer felt that the outcome would be inevitable. Any attempt at revolution in Ireland had to end ‘in the defeat and slaughter of the poor misguided people, out of whom a set of hungry agitators are endeavoring to extract a living for themselves, perfectly careless of the fate in which they may possibly involve their unfortunate dupes’ (8 July 1848, 7). On 12 July, a day traditionally given over to Orange celebrations in Ireland, the Guardian announced that John Mitchell and Gavin Duffy had been committed to trial for publishing ‘treasonable incitement, which is but too well calculated to deceive an ignorant and excitable people like the Irish’ (12 July 1848,4).

In July of 1848, as Parliament debated whether to continue relief for Ireland, the Young Irelanders began a push toward a more radical solution. The Scotsman on 22 July 1848, reported on a meeting of the Irish League in Drogheda where ten thousand people turned out to hear William Smith O’Brien, one of the strongest advocates of physical force. Though small compared to the monster meetings O’Connell had marshalled, Smith O’Brien’s willingness to use force made the gathering seem dangerous to British observers. With some of his former comrades in jail or transported, Smith O’Brien used very circumspect language: ‘I shall not gratify Lord Clarendon [the Lord Lieutenant] by enabling him to put me into the jail of Newgate or of Drogheda.’ Instead of rousing his audience by his own words, Smith O’Brien referred instead to the words of his supporters:

…since I have come to this town, I have heard some very fighting cheers; I have heard sundry expressions, which intimated to me that the vast concourse, which I now behold with so much pleasure have fully determined on obtaining their nationality (Scotsman, 22 July 1848,2).

In the same issue, the Scotsman reported that at a later meeting in Dublin, Smith O’Brien hinted at a rising. According to the paper, he stated that if Clarendon was resolved to block nationalist agitation, ‘100,000 of the men of Kilkenny, Carlow and Tipperary were ready to walk up to Dublin’ (22 July 1848, 2).

Smith O’Brien’s carefully phrased calls for action seemed to bear fruit in an incident at Carrick-on-Suir in which armed men sought revenge for a missing local leader of an Irish League club. A few shots were reported fired at the suspected abductors, producing a great deal of local excitement. According to the Scotsman,

The intelligence of the ‘rising’ at Carrick-on-Suir was received all through Tipperary with enthusiasm. On Monday night the mountains were all in a blaze with fires from Slievebloom to Slievenamon, and the peasantry crowded around them in large masses. The cheering along the Waterford range was heard in Clonmel, and the [nationalist] clubs turned out to do homage to the general enthusiasm (22 July 1848,2).

The Government responded by putting the army on alert. The Scotsman reported in its military news that ‘all Officers belonging to regiments in Ireland on leave of absence in London [are ordered] to… rejoin their respective regiments quartered in that country’ (22 July 1848,2).

As the army and police prepared for a rising, the rhetoric in Ireland, as reported in the press, became more and more heated. According to one report, Charles Gavin Duffy had written from Newgate prison: ‘We bade England…choose speedily between concession and the sword. We formally proclaim a war of independence. And now the time is when that pledge must be promptly fulfilled or as formally dishonoured’ (Scotsman, 26 July 1848,2).

One over-anxious paper ran a story announcing the start of a full-scale rebellion. On 26 July The Times reprinted an account from the Dublin Evening Post, reporting that ‘The whole of the south of Ireland is in rebellion…. At Clonmel the fighting is dreadful. The people arrive in masses. The Dublin club leaders are there. The troops were speedily overpowered; many refused to act.’ The willingness of The Times to publish this hysterical fiction suggests the extent to which portions of the British press anticipated, perhaps hoped for, a rising in Ireland.

The Times’ leader for the same day worried that the British Chartists might support an Irish uprising. Delane’s writer argued that the Chartists’ desire to better the lot of the English working man should surely set them against the Irish. Not only were there ethnic differences between the two groups, but, the paper insisted, the Irish were an economic burden upon the English worker.

The English are very well aware that Ireland is a trouble, a vexation and an expense to this country. We must pay to feed it and pay to keep it in order. We are paying its paupers, its labourers, its policemen, its soldiers, its sailors. Ground down with taxes, we are told year after year that no taxes can be removed [from England] while Ireland is expensive….

The leader then summed up the burden of Ireland in a vivid image.

Taking all things into account, we do not hesitate to say that every hard-working man in this country carries a whole Irish family on his shoulders…. [T]he said Irish family…is doing nothing but sitting idle at home, basking in the sun, telling stories, going to fairs, plotting, rebelling, wishing death to the Saxon and laying everything that happens at the Saxon’s door… suppression of the rebellion will cost several millions, every farthing of which will come out of the pocket of the British working man. As an unfriendly French journal observes, with some glee, we shall have to conquer the Irish and then feed them, both at our own cost (The Times, 26 July 1848, 6).2

The image of the Irish peasant ‘basking in the sun’ suggests a lively imagination rather than familiarity with Ireland.

In anticipation of rebellion spreading to the ever-growing Irish population in Liverpool, The Times’ writer concluded that, ‘If the Irish porters and coal heavers of Liverpool attempt a row, they are fighting against nobody so much as themselves…. Once unsettle England, and credit, enterprise, employment and wages fly away’ (6). Reassuringly, the paper reported that 20,000 special constables were in Liverpool itself (26 July 1848, 8). Britain was braced for violence at home, as well as in Ireland.

The Irish Revolution of 1848 was slow to materialize, however. The Manchester Guardian for Saturday, 29 July contradicted the Evening Post’s earlier report, carried by The Times, of a bloody rising in the south. It proudly published ‘THE LATEST NEWS FROM IRELAND (By Electric Telegraph)’ with a very precise dateline:

Dublin Friday Morning Five O’Clock. —All the inland mails have arrived, and there is no disturbance whatever reported in any part of Ireland. Considerable excitement prevails in the part of Tipperary, where Smith O’Brien is located, but all is quiet. There being no occasion in the country for additional troops, the 85th remain in this garrison.

The leader on the same page criticized the kind of anticipatory fictions that other papers had published: ‘There have been so many postponements of the great event [the Irish insurrection], that we have become perfectly incredulous as to each successive announcement of its approach’ (Manchester Guardian, 29 July 1848, 6)

Undaunted by its earlier hysteria, the Dublin Evening Post produced a less sensational report, which was duly reprinted in The Times on 31 July.

On Tuesday, [23 July]…Mr. W. S. O’Brien, M.P…arrived in Millinahone…[to] address a large multitude…. [T]he chapel bell was rung to collect the people…. The Rev. Daniel Corcoran, P.P. and his curate, the Rev. Wm. Cahill, immediately repaired to the spot, and requested them, in the name of religion, to respect and obey the laws — beseeching them at once to abandon the mad policy they were then about to pursue…declaiming out loud…against the abominable doctrine they were endeavoring to promulgate to a starving but peaceable people (The Times, 31 July 1848, 8).

The tradition of O’Connell’s ‘moral force’ still held, but, according to the Scotsman, Smith O’Brien tried another tactic the following morning:

About nine o’clock Wednesday morning, Mr. S. O’Brien and his comrades, unaccompanied by any person whatever, rather silently dropped into the police barracks, and for some time questioned the temper and feelings of the police of this station, and as rumour states, requested them to surrender up their arms to the people — a mandate with which the police very properly refused to comply (Scotsman, 2 August 1848, 2).

When the townspeople of Millinahone discovered his attempt to suborn the police, O’Brien was reportedly escorted out of town by a body of enraged citizens. The Scotsman then chronicled Smith O’Brien’s movements over the next few days as he traveled around the area and returned to Mullinahone. Although ‘accompanied by a number of peasantry,’ the Reverends Corcoran and Cahill again apparently dispersed them, leaving ‘Mr. Smith O’Brien and comrades almost alone’ (Scotsman, 2 August 1848,2).

Few rebels in search of a revolution have been as well covered by the press as was William Smith O’Brien, whose quest finally ended on 29 July in Widow McCormack’s cabbage patch on Boulagh Common near Ballingarry, Tipperary. Smith O’Brien and about 100 men (reported as four or five hundred in some accounts) confronted a party of about fifty members of the Irish constabulary with a view to seizing their arms. The policemen barricaded themselves in Widow McCormack’s house. William Smith O’ Brien himself walked up to the front door of the house and, shaking hands with the chief constable, asked him to surrender his arms. Secure in the stone house, the constables fired a reported 250 cartridges at the nationalist crowd who gradually dispersed under the rain of fire (R. Davis, 161).

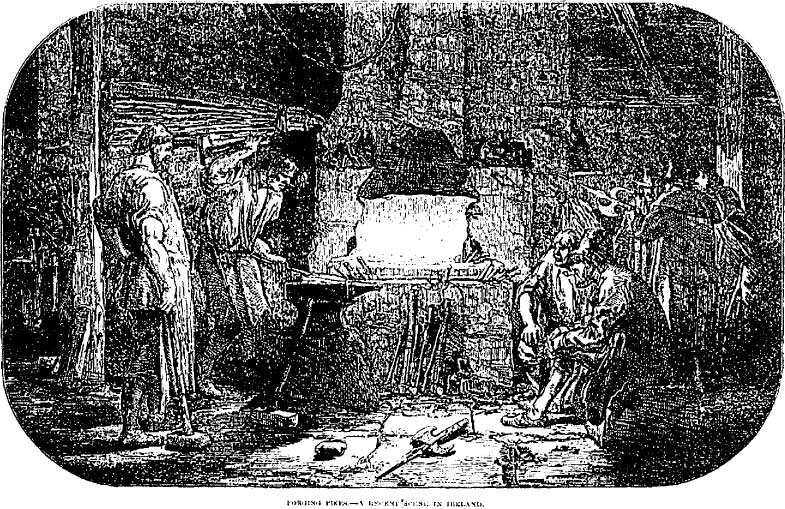

Less than a week after the action at Boulagh, but before it could report the skirmish, the Illustrated London News featured on the front page of its issue for 5 August a large, half-sheet wood engraving titled ‘Forging Pikes — a Recent Scene in Ireland.’ The illustration shows a dark, fiery smith’s shop where brawny, demonic-looking Irishmen labour at a hellfire forge, beating out pikes for an uprising (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Illustrated London, News, xiii. (1848), 65.

A week later the Illustrated London News published an account of ‘the rising.’ On the front page there was an illustration of the siege of the McCormack house, depicting the insurgents, sheltered behind a wall, armed with only ‘a miscellaneous assortment of pikes, pitchforks, spades, shovels, scythes, reaping-hooks, blunderbusses, fowling pieces, and pistols.’ The rebel group is shown in a mass of confusion, with two men scrambling on their knees like dogs. One of the two rebels killed in the fray is shown toppling from the wall (Figure 12.2).

The Illustrated London News’ reporter sometimes had difficulty maintaining an appropriate degree of gravity in describing the ‘rising.’ Though he stated in the strongest terms that ‘The Irish are not cowards,’ nevertheless, when he listed the retreat of ‘pikemen, spademen, scythemen, and carriers of blunderbusses,’ he was, by these mock military designations, clearly ridiculing his subject.

Without arms and with very few remaining followers, Smith O’Brien rode west to rally more men, but everywhere he went, his former supporters, according to the Illustrated London News, ‘shrank back and advised that the war should begin somewhere else’ (90). William Smith O’Brien was eventually arrested at the Thurles train station. The ILN ran an engraving of a policeman apprehending the Young Irelander with the traditional clap on the shoulder, as if he were any common thief or debtor (92).

The same issue of the Illustrated London News included a series of illustrations by James Mahony, who had reported on the Famine the previous year. Starting with scenes of Slievenamon and other picturesque views of ‘The Typography of the Insurrection,’ the artist depicted ‘some of the precautionary measures’ which the Crown forces were taking to secure the country. Even the titles of the wood engravings gave a sense of activity and preparedness: ‘Delivery of dispatches at Lismore Castle,’ ‘Posting proclamations,’ ‘Camp fire and sentinels,’ and ‘Searching for arms.’ There were also illustrations of military encampments in Liverpool and in the Phoenix Park in Dublin, as well as a scene of the officers’ mess of the 74th Highlanders (92-93). The empire was clearly ready and in control.

Figure 12.2 Illustrated London News, xiii. (1848), 81.

Tucked into the midst of its reportage on this massive military response to an almost comic-opera rebellion, the Ilustrated London News turned momentarily to a brief account of ‘THE HARVEST AND POTATO CROPS.’ Writing of the eastern and central counties, the reporter noted:

Ireland only requires a few weeks of sunny weather to possess one of the best harvests of many years. Everywhere it is luxuriant. But since I came here the weather has been often wet, always cloudy.

Of the potatoes, I read bad accounts, and occasionally hear people’s fears…but I have never seen a better growth, or a healthier bloom upon potato fields…. In no marketplace, in no shop, at no dinner table have I yet seen a diseased potato. On some of the earlier sorts of gardens I have seen withered leaves and in the fields where the seed failed I have seen blanks; but if there be disease, it is but imperfectly developed (Illustrated London News, xiii., 12 August 1848,92-93; italics original).

With that somewhat hopeful reminder of the on-going crisis of famine in Ireland, the writer returned to the more interesting subject of insurrection.

The Illustrated London News, whose sales had doubled during the three months following the revolution in Paris, may have been a bit disappointed in the rapid deflation of the Irish rebellion story. (Jackson, 302). Certainly, Mackay seems to have had material already prepared to accompany something greater than the cabbage-patch skirmishes at Boulagh. Perhaps unwilling to throw away good illustrations, Mackay published in the 26 August issue a single-column illustration of a ragged young man and a friend ‘going for a license to keep firearms’ for an old blunderbuss. The men are shabbily dressed, with holes in their coats, half-buttoned waistcoats and open-throated shirts (118). The text surrounding them had nothing to do with arms or the late rising. Instead, the report concerned the efforts of government-sponsored instructors attempting to teach the Irish how to cultivate grain. The article stated that it was almost impossible to get loans to buy seed, or to ‘obtain food while the crop is growing.’ Loan rates were twenty to forty percent. The writer claimed that the peasants preferred working on the roads, ‘like convicts in a penal colony,’ while their own land lay untilled.

It is beyond the power of human knowledge to devise a plan by which these people are to be made men of substance, unless the plan of Lord Clarendon, of teaching them how to make their land fertile and their crops profitable, be followed out, in conjunction with such aid in seeds and implements as other funds may for a time assist them in procuring (26 August 1848, 118).

Trevelyan had publicly rejected such schemes earlier in the year.

As was becoming typical of the Illustrated London News, the 26 August issue carried very mixed messages. While the article reported some positive responses from the agricultural instructors, the picture of the two young, disheveled men with a gun may have suggested to the journal’s readers that Ireland was more interested in violence than in agricultural reform. Yet, Mackay’s preceding page featured peaceful ‘Irish Sketches,’ depicting the market at Thurles with loads of peat and hay, but very little produce for sale. Another illustration showed an interior of an Irish chapel (117).

With the much awaited Irish rebellion of 1848 turning into a damp squib, The Times did its best to turn attention away from its earlier warnings of bloody revolution. Now it reverted to mockery.

The Iliad in a nutshell is not a greater curiosity than an Irish rebellion in a column and a half. Yet there it all is. There is the anger of the gods in the shape of a proclamation offering rewards for the apprehension of the traitors, and there is the wandering hero, fato profugus, the Jove-born O’Brien. There is only one scene—the slate-house on Boulagh-common; and the time not quite an hour.

Perhaps this is trifling with a very grave crime and a crisis of actual danger, but certainly never did rebellion make itself so ridiculous. The whole affairs had collapsed in a moment. The public were assembled for a magnificent spectacle …Never was there such a bubble…The perpetual puffing and blowing and trumpeting we have had so long has deceived nobody so much as the traitors themselves…The rebellion turns out to be a great sham (The Times, 1 August 1848, 5).

The great fear of an Irish revolution, galvanized by the murder of Major Mahon the preceding November, had turned into the great Irish joke. The joke was, of course, primarily on the British press, which had convinced itself that the Irish were as ready to produce a rebellion as the press was to report one.

Whatever modicum of humour The Times saw in the situation was quickly replaced, however, by a return to its customary lofty seriousness. In September it urged the Government to declare martial law and to have a military court deal with Smith O’Brien and his co-defendants.3 Ignoring the fact that the vast majority of Irish peasants who, having been offered the opportunity to rebel, had rejected it, the paper’s leader confidently equated the Irish with other restless savages of the Empire. ‘There is one law for robbers and murderers, whether they be called Mahrattas, Thugs, Caffres or Celts…. Such of the enemy as are taken in arms, or found otherwise assisting the rebel cause, must be dealt with as enemies and traitors’ (quoted from the Manchester Guardian, 23 September 1848, 7).

In the midst of the uproar surrounding the State Trials, ‘A Constant Reader’ from Thomastown in Ireland chided The Times for continuing to depict the Irish countryside as in a state of turmoil. On the contrary, the correspondent wrote, Ireland was very peaceable. He noted that the sale of cattle at Castle Morris took place in mid-September without incident. ‘Gentry, tenantry, and peasantry…crowded together…. All parties appeared to be in good-humour with one another – not an angry word, not a gesture of disrespect….’ Referring to press depictions of Ireland as a seething cauldron of hostility, the writer complained to The Times’ editor,

Surely, Sir, this is a very mild form of insurrection; surely it is hard, very hard…that England should be frightened…and the Government coerced into severity by overcoloured accounts of the state of a district in which the peaceful…scene…took place…. [T]o confound the screams of distress with the war-cry of rebellion, to infer general disloyalty from partial discontent, is alike unjust to the people and to their rulers, and has the mischievous effect of diverting the attention of the Government and people of England from the real character of the evil with which they have to deal, thereby rendering its alleviation difficult if not impossible (The Times, 23 September 1848).

This was an attack on The Times’ own highly colored reporting of the attempted rebellion, as well as on the paper’s generally anti-Irish editorial policy. The Times responded with the paper’s favorite method for disposing of any opinion it opposed by sarcastically ridiculing its author’s argument.

A correspondent, whose letter we publish today, throws a new light upon Irish affairs. Ireland is in a state of calm beatitude. Apprehension of distress during the coming winter there may be, but distress there is none at present. We have all of us been in a dream…. If this be so, it would be difficult to assign any more valid reason for emptying the public treasure yet again into the laps of the Irish landlords…(The Times, 23 September 1848).

Delane’s leader insisted that Ireland remained ‘fully in as disturbed a state…. Guerilla parties of the peasantry are openly scouring the country in all directions, and but for the unceasing vigilance of the military and police, where a rebel party consists of hundreds today, it would number thousands tomorrow’ (The Times, 23 September 1848). Yet, in spite of The Times’ insistence that Ireland was still on the verge of chaos, martial law was not declared. Instead, the State Trials of the Young Irelanders went forward and the country, if not tranquil, was not in turmoil. Occasionally, there was local resistance to evictions, but nothing on the scale of which The Times and other papers expected.

During the trials, the Standard, the epitome of an Ultra Tory paper, urged that several Catholic priests be arrested and tried for their alleged part in the rising. Alluding to the fact that the Irish Attorney General was a Catholic, the Standard insisted that ‘the government is in the hands of Romanists…[who] have secured and still obstinately suppress all the documentary evidence against the priests.’ This was too much for the Manchester Guardian, which, in reporting it, insisted ‘that the Roman catholic clergy saved the country from a vast deal of bloodshed and misery. Had they striven to incite the people to insurrection, the consequence of the outbreak would not have been confined to the fight at Ballingarry and the robbery of a mail coach’ (7 October 1848,6). The Guardian questioned the motives of both the extreme Protestant papers and the organs of the Repeal Association. It argued that

the orange and repeal newspapers of England and Ireland have been working zealously, and in perfect accord, to defeat the government prosecutions;—the repealers for a motive sufficiently obvious; the orangemen in the hope of so damaging the present government as to render it incapable of preserving order in Ireland, and thereby obtaining a chance of restoring the rule of the old protestant ascendancy, in all its former power, and with all its past bigotry and cruelty (Manchester Guardian, 7 October 1848, 6).

At the State Trials Smith O’Brien, when at first condemned to death, replied to the judge that he had done his duty. He returned to his cell with ‘a steady step and smiling countenance.’ His fellow Young Irelanders, Meagher, O’Donohoe and McManus were also condemned, but all four had their sentences commuted by special legislation to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. Smith O’Brien was released six years later, and was finally allowed to return home to Ireland in 1856 (R. Davis, 164-167).

Once the Young Irelanders’ trials were over, the Illustrated London News had to shift its attention back to the continuing shortfall in the Irish potato harvest. The mildness of the blight in 1847 had encouraged an increase in potato acreage. The following year, however, the blight, while not universal, was severe in the areas where it struck. Famine conditions continued in many parts of Ireland (Kinealy, 228). On 25 November 1848 the ILN leader regarding the Irish Poor Law stated:

The approach of winter brings the usual cry of distress from Ireland. As the interest of the political trials dies away, a new and far more painful interest is excited by a certainty that a widespread destitution will afflict the country…the failure of the potato crop may have been partial, not general…. Vast numbers of emigrants may have fled from those fatal shores to seek a better fortune over the Atlantic, but sufficient misery, and a sufficiently deplorable pressure of mouths to be fed upon the supply of food to fill them, remain in Ireland, to tax to the utmost the benevolence of the wealthy, and to afford room for all the statesmanship of this country in providing a remedy or even an alleviation (xiii., 25 November 1848, 321; italics added).

Mortality rates remained high. Yet Mackay’s leader referred to the famine conditions in impersonal, almost dismissive language. References to ‘the usual cry of distress’ and ‘sufficient misery,’ may have distanced readers from the crisis, while continuing the myth that disaster was a near normal state for Ireland. Given the Illustrated London News’ language, some readers might have found it hard to sympathize with what the paper called the ‘overabundant people — from the immense potato-feeding multitudes…’ (321).

Like Trevelyan, the Illustrated London News found it easier to blame the past than to suggest amelioration for the present. ‘The misfortune in the case of Ireland is, that the Poor-Law was not applied generations ago — before population had increased to such an extent — before the people under its pressure had been reduced to the lowest and most precarious diet, the potato…’ (321). Population pressure and the impoverished state of the Irish landlords were blamed for making the Poor Law, which was considered so appropriate to England, unworkable in Ireland. As a result, ‘The cry of distress’ arose not just from the peasantry but also the classes both ‘immediately and high above them.’ Strong farmers, middlemen and landlords were all in serious trouble. For the ILN, it was no longer simply a problem of the starving poor, but also of the dissolution of society’s hierarchical economic structure (321). Happily, however, the social order in the capital city of Dublin was still intact. As a contrast to the grim ruminations on its front page, the 25 November issue of the ILN carried on the inside a half-page wood engraving of the guests in evening dress at the ‘Grand Banquet to Liet. Gen. Sir Charles James Napier, G.C.B., at the Rotunda, Dublin’ (328).

While the Illustrated London News was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Poor Law in Ireland, the Manchester Guardian maintained a more consistently Whiggish line. The Government’s policies, it held, were a necessary corrective that would eventually force the Irish to stand on their own feet. The Guardian dismissed the Irish as exploiters of English generosity, hinting that starvation was a poor excuse for dependency.

Everybody is familiar with the unceasing importunity of Irish pauperism, dinned into the ears of this country in every conceivable tone, and in every possible shape; most people know what large sums have been expended for its alleviation during the last two or three years, both by public grants and private English benevolence; but very few, we dare say, have ever inquired closely how much the Irish themselves have contrived to scrape together for the purpose… (Manchester Guardian, 9 December 1848, 7).

The paper cited the alleged gap between what the Government and private British charity had given to the Westport Union in County Mayo and the rates collected from the Union, which, it claimed, were a mere five pence in the pound. The paper did not mention that the collection of rents had dropped critically in western counties such as Mayo. With lowered income, many landlords, especially those already in debt, were having a hard time paying rates that had been rising over the past several years.

Significantly, the Manchester Guardian made no moral distinction between the Irish landlord and the Irish beggar. In a marvelous non sequitur, having indicted the landlords, the paper went on to conjure up the image of an impecunious Irish immigrant in England, who

will whine for halfpence in the street, or demand relief in a workhouse, while he has bank notes sewn in the lining of his apparel. It is another instance of the certain effect of habitual eleemosynary aid on the mind of the recipient, the blunting of the moral sense, and the relaxation of principle, with the loss of independence (Manchester Guardian, 9 December 1848, 7).

Since ‘habitual’ pauperism was believed to blunt morality, continual poverty was simply an immoral state, even when occasioned by a circumstance as unavoidable as crop failure. ‘Mere misfortune,’ the once forgivable road to pauperism, no longer justified dependence, especially when the cost of dependence was imagined to fall more heavily on the English taxpayer than on the Irish landlords.

Nevertheless, as the year came to an end, Mackay’s Illustrated London News began to question the situation in Ireland. With more sympathy for the Irish peasants than he had previously shown, the editor focused on the growing number of evictions. Just before Christmas, in the 16 December issue, the ILN printed two powerful illustrations depicting the ‘Ejectment of Irish Tenantry’ (Figure 12.3). The first picture, ‘The Ejectment,’ dramatically showed an Irish family being evicted. In the center the woman of the house begs a mounted figure, probably the landlord or his agent, to spare the cabin, as her roof is unthached and her family’s meager possessions are carried outside. To one side, soldiers with fixed bayonets stand guard, while in the background the family’s stock is driven off for the rent. At the bottom of the page ‘The Day After Ejectment’ depicts the evicted tenant standing in despair, his face buried in his arm, while inside a make-shift hovel his wife nurses a child. At the man’s feet stands one of the family’s few possessions, an earthenware jug, which also appears in the preceding picture.

‘A vast social change is gradually taking place in Ireland,’ the brief accompanying text explains. Emigration of small capitalists and the eviction of the tenantry would soon ‘render quite inappropriate the old cry of a redundant population. But this social revolution, however necessary it may be, is accompanied by an amount of human misery that is abundantly appalling.’ The Illustrated London News then reprinted a short piece from the Tipperary Vindicator. ‘We do not say that there exists a conspiracy to uproot the “mere Irish;” but we do aver, that the fearful system of wholesale ejectment…is a mockery of the eternal laws of God….’ Taking note of the time of year, the Vindicator concluded: ‘Christmas was accustomed to come with many healing balsams…but its place is usurped by other and far different qualifications. The howl of misery has succeeded the merry carol…’ (16 December 1848, 380).

The Illustrated London News’ reports and wood engravings of evictions may have been intended to raise sympathy for the victims, although Stephen J. Campbell surmises that this type of coverage might have had an opposite effect. The image of Irish families standing by unresistingly, as their cabins were emptied and unroofed, may have reinforced the stereotype of the Irish peasant as a passive spectator of his own disaster (43). Such views, of course, ignored the fact that evictions were backed by considerable force, as can be seen in the ILN pictures. Not only does the ‘Ejectment’ record the presence of armed soldiers, but also on the same page the magazine carried a note, ‘The Army in Ireland,’ listing the thirty-six regiments then stationed throughout the country. (This did not count the nine regiments, normally based in Ireland, then on colonial service.) Readers were reassured that ‘There are also strong detachments of Artillery, Marines, Royal Engineers, Out-Pensioners, and armed policemen,’ as well as the Coast Guard, making a grand total of some 50,000 men (380).

Figure 12.3: ‘EJECTMENT OF IRISH TENANTRY,’ Illustrated London News, xiii. (1848), 380.

While the page devoted to Irish evictions, so close to the holiday season, may have disturbed some readers, there was no hint of Irish distress in the Illustrated London News’ next issue, its Christmas special for 1848. Large, well-fed English families were shown sitting in circles of domestic comfort. In one illustration, however, pathetic sweeps, clad in rags against the December snow, watch a countryman in a smock selling holly to a maidservant. Yet, on the same page men and women from various levels of English society are depicted bringing home the Christmas roast from the baker’s oven (Figure 12.4). Exuding self-satisfaction, everyone in the picture has some sort of dish, except for one dirty little beggar boy receiving a potato from a rather apprehensive but generous young girl. This personal act of charity is singled out and lavishly praised in the accompanying text. This was, no doubt, intended as a reminder of the season’s appeal for charity. It may also be taken as a reminder of how carefully British Victorians doled out their charity, whether the beggar was English or Irish. On the page opposite this illustration was a full-page woodcut of the Royal Family trimming Prince Albert’s famous Christmas Tree. In contrast to the previous issue that acknowledged Irish travail, the ILN’s Christmas issue looked inward in what Peter W. Sinnema has called ‘the identification of Englishness with the “authentic” celebration of Christmas’ (110).

In its last issue of the year, 30 December, the Illustrated London News published ‘New Year’s Night in an Irish Cabin — Drawn by Topham’ (434). A throwback to the more sentimental era of Frederick Bayley, the engraving depicts a boy and girl in a carefree dance before the cabin’s hearth. Nothing could have been a less appropriate symbol for Ireland at the end of 1848.

Notes:

1. ‘Introduction’— ‘Political Summary,’ for Punch, volume xv., July to December 1848, no page number.

Figure 12.4: Illustrated London News, xiii. (1848), 408.

2. About a year after this leader appeared, Punch produced the visual equivalent of the image of the English carrying the Irish. ‘The English Labourer’s Burden; or, The Irish Old Man of the Mountain [See Sinbad the Sailor]’ depicts a grinning, simian-like Paddy riding on the shoulders of an English workingman. The Irishman carries a sack labeled ‘£50,000.’ This referred to the grant-in-aid offered to insolvent Poor Law Unions. Punch, xvi. (1849), 79.

3. A court marshal would have eliminated the need to select a jury. Both the Manchester Guardian (23 September 1848, 7) and The Times described potential jurors as afraid to sit in judgment over the popular prisoners.