Four

STAGNATION

1913–1950

Growth in Paducah did not slow even after the 1913 flood; however, the 1937 flood that forced 20,000 people to flee Paducah and inflicted millions of dollars worth of damage to the community was another matter. Because of the flood coupled with the Great Depression, Paducah entered a long period of economic stagnation. It was not until the floodwall was finished in 1946 that recovery began and bloomed with the arrival of the “atomic plant” in 1950.

Charles Wheeler poses with his sisters. Wheeler served the First Congressional District of Kentucky from 1897 until 1903. On leaving office, Wheeler gave this carefully considered advice to aspiring politicians: “I would not advise anybody to enter politics unless he is very poor or very rich. If poor, he had not much to lose.... If he is rich he has a better chance of enjoying his experience.”

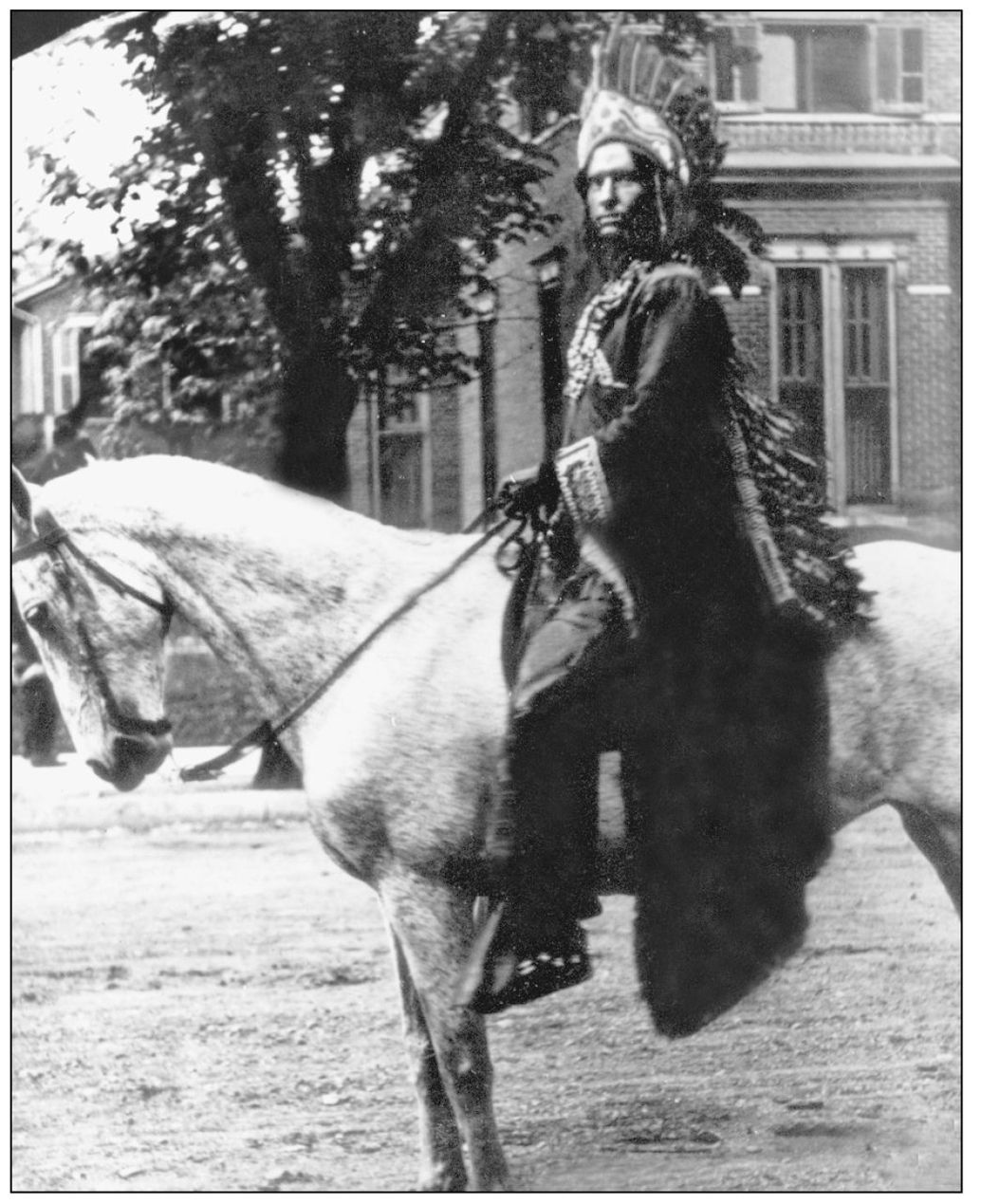

“Homecoming week, May 19 to May 24” was celebrated in 1913, complete with the arrival of James Wheeler as the legendary Chief Paduke. The city had weathered the recent flood, cleaned up its image by ridding the city of over 300 prostitutes, and looked forward to a bright future. Mayor Thomas N. Hazelip gave Paduke a welcome before a joyful crowd of thousands near the post office at Fifth and Broadway.

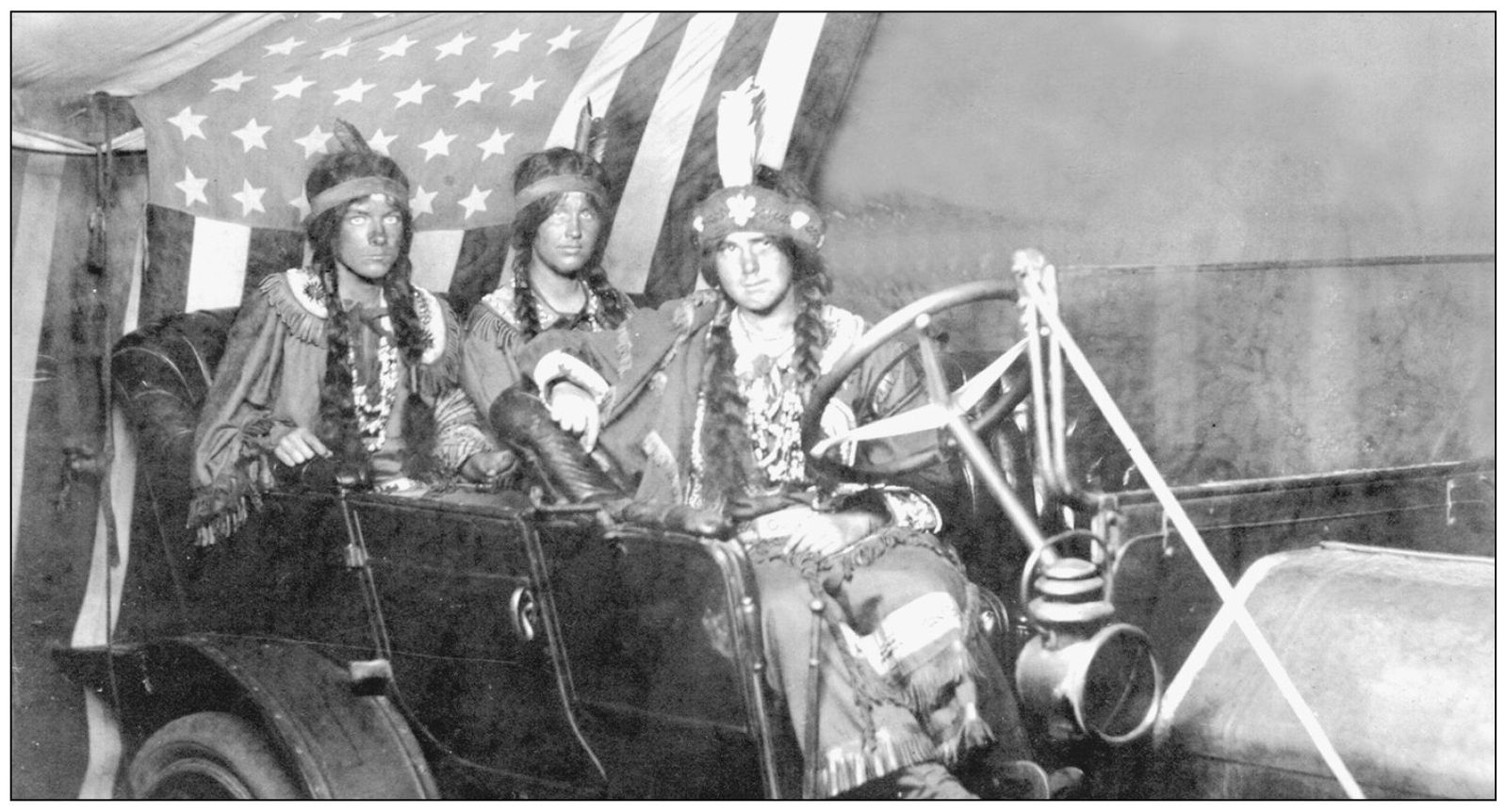

Accompanying the legendary Chief Paduke in 1913 were, from left to right, “Princess” Adine Corbett, Ruth Hinkle, and Bertha Ferguson as maids of honor. Wheeler arrived at the foot of Broadway, descended from steamer G.W. Robertson, mounted his horse, and rode to Fifth and Broadway. Later, Wheeler married Miss Ferguson. Wheeler promoted equestrian skills, especially the art of dressage. A love of horses and the pleasure of riding them captivated Wheeler into his 90s.

In 1916, war loomed in Europe, and American troops were busy chasing Francisco “Pancho” Villa in Mexico to no avail. Villa had killed Americans at Santa Ysabel and had raided into the United States at Columbus, New Mexico. These events were noted in Paducah but the visit of a circus took priority. Barnum and Bailey opened with a grand parade that brought both beautiful and bizarre attractions to the amazed city.

Women made a significant contribution to the effort to end “the war to end all wars” in 1917–1918. One avenue for such participation was with the Red Cross. Bandages had to be rolled and sent to the front in France. A 1918 drive for $25,000 collected $40,000. The city was also most generous in the Liberty Bond drives. In one, a float with electric lights came from St. Louis.

The winter of 1917–1918 produced blizzards that piled heaps of snow on Paducah and the surrounding area. Digging paths downtown created shoulder-high snow “trenches” from store to store. Approximately two feet of snow proved to be an irresistible lure for those young at heart to frolic. Fred Neuman reported that this was “the heaviest snowfall since 1864.” The Tennessee River froze to a depth of eight inches on January 14.

The cold winter of 1917-1918 also played havoc with shipping. The narrow passage between Owen Island and the bank of the Tennessee River, called the “chute,” captured several steamers and barges in thick ice. Pictured is the city wharf boat at the mouth of the chute just before the thaw began on January 18 that sank many vessels and damaged others with claims in excess of $1 million.

Three women in this Ford avidly anticipate the open road. Note that Henry Ford had not yet decided if the steering column would be on the left or the right. He preferred the English example at this time. Also note that the car does not have a left-hand door. Driving was for the hardy. Set the spark and throttle levers like a clock at ten and then crank.

Automobiles came to Paducah in 1901 when an Oldsmobile arrived for Dr. J.D. Robertson. The Evening Sun reported the vehicle was the “first of its kind owned by a Paducah man.” A shipment of Fords arrived on June 14, 1904. By 1919, automobiles still held an aura of affluence and were used by a local photographer as a prop. Note the attire of the young African-American woman complete with driving gloves.

Albritton’s Drugs, shown here in 1931, was the point of gathering for young people in Paducah from the 1930s to the 1980s. Needless to say this business was strictly a family enterprise; the Albrittons are, from left to right, Charles E. Albritton, Lawrence E. Albritton, Walter E. Albritton Jr., John Harper Albritton, and Walter E. Albritton; Marilyn R. Albritton Simpson is not shown. The store was one of the first “drive-in” establishments in town. Located at the demarcation between the flood-prone zone toward the river and the emerging affluent residential west end, the store was the “place to be” for Paducahans who fondly remember ordering delicious “Chip Chocolate” ice cream and the nickel “hot ham” (fried bologna) sandwiches. For a while, the Albritton family lived in a house behind the store. Later this was moved to Jefferson Street. The city tram ended behind the store on Jefferson. A brief walk across LaBelle and one always felt welcomed at Albritton’s.

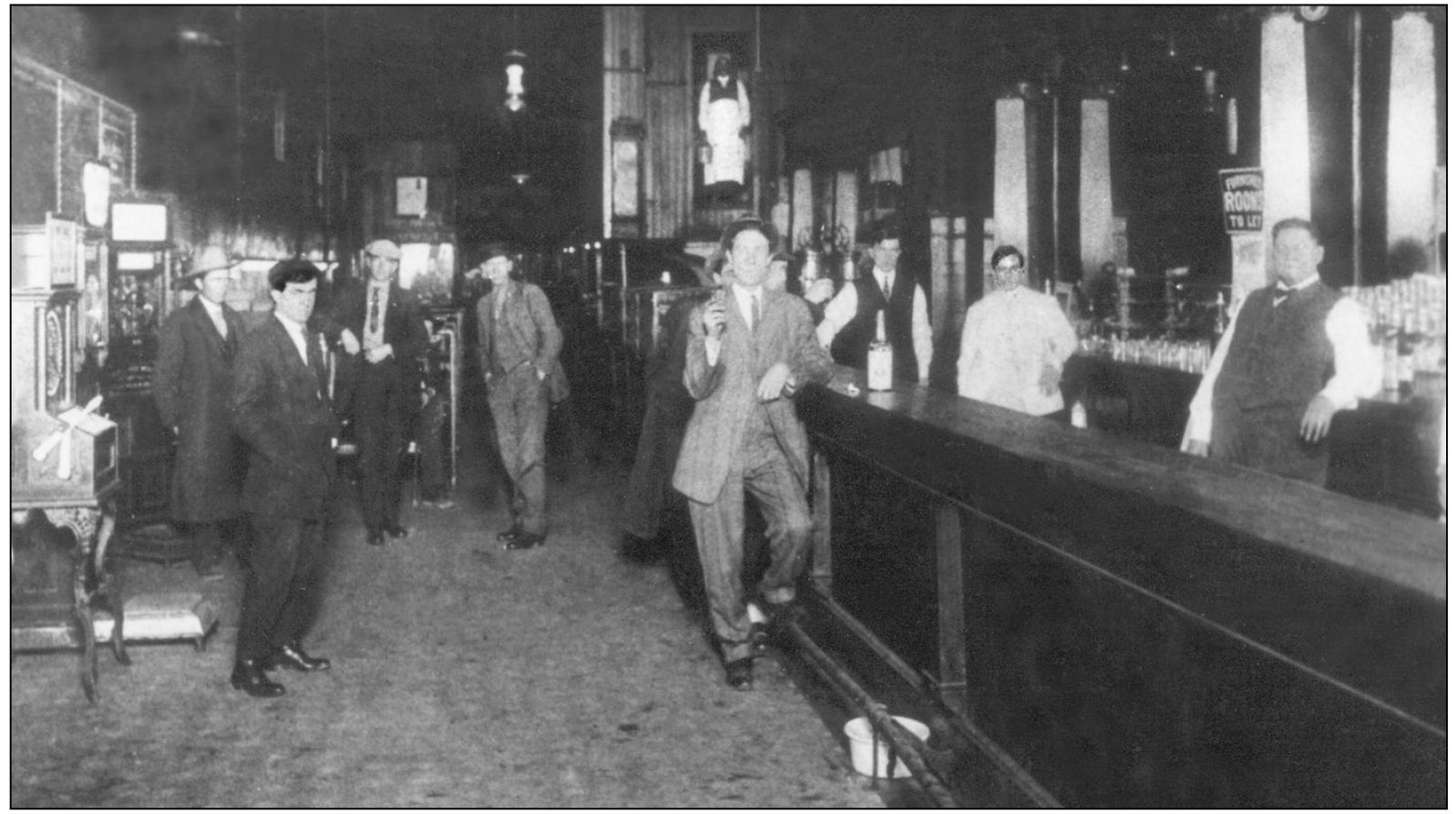

After making the world “safe for democracy” in 1918, reformers went further. They ended the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages and they gave women the right to vote. In Paducah a favorite watering spot met the “Brave New World” with grim determination. They installed a soda fountain and pool tables, and the patrons grew younger. The vote for women proved successful; Prohibition was less well received. The law was often ignored.

Henry Steinhauer and Tyler White purchased S.B. Gott’s saloon at 119 North Fourth Street in 1917. Prohibition brought “near beer” in 1919 but never ended the yen for good brew in Paducah. In 1933, lager returned; however, Heinie and Tyler’s served only men. Until 1969, women at Citizens Bank wishing for the famous oyster sandwiches at noon had to send Bane Barton, the bank’s porter, to the “take-out” window.

Irvin S. Cobb left Paducah as a young man but kept a fond regard for his birthplace. Cobb went to work at 16 on The Paducah Daily News and became its night editor three years later, only to get into legal trouble because of his lack of experience. Cobb went to Louisville with the Evening Post and gained recognition as an excellent reporter. In 1901 Cobb returned to Paducah as editor of the Democrat until 1904, when he moved to the East Coast and his career took off. He became a famous war correspondent in World War I, a noted and respected reporter, a humorist with a flair for the curious turn of a word, an author whose use of dialect rivaled that of Mark Twain, a lecturer, a movie actor in Steamboat Around the Bend with Will Rogers, and Paducah’s first “Duke.” Cobb’s autobiography, Exit Laughing (1941) is a national treasure. In 1928, a hotel was named in Cobb’s honor.

After 1929, the Irvin Cobb Hotel, named for favorite son Irvin S. Cobb, quickly became the center of social life in Paducah until a fire damaged it in 1972, leading to its reconstruction as apartments for the elderly. In its heyday, debutantes and dandies flocked to the ballroom for festive evenings while various civic clubs met regularly in its dining room. In the 1940s an elegant maitre d’hotel supervised this staff of young men in proper decorum.

Unlike Louisville and other cities, Paducah did not have one principal segregated area for its African-American citizens in the mid-20th century; still, each race had its distinctive culture that flourished in its principal areas. Movies had separate entrances. There were no toilet accommodations just for African Americans downtown. In each culture there was a marked division between youth and mature adults, especially in clothing and behavior.

Cobb returned to Paducah for the celebration of his 50th birthday on June 23, 1926. While in town he was wined and dined at the Women’s Club auditorium and honored at the Carnegie library. Among his many causes was opposition to the Klu Klux Klan. Cobb even returned to Paducah in 1923 and edited one issue of the local paper that helped prevent the racist organization from meeting in the city.

Wallace Park, at Thirty-Second and Broadway, hosted Paducah’s baseball teams between 1904 and 1908. After 1927 they played at Hook’s field, at Eighth and Terrell Streets. The Chiefs, resurrected in 1947, played at Brooks Field. The franchise was part of the Milwaukee Braves system in 1949 as part of the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League and changed to the Kitty League in 1951 with relations to the St. Louis Cardinals. Television decreased interest in local sports.

Social functions frequently involve banquets honoring various citizens and causes. The Illinois Central Ladies auxiliary met at the Irvin Cobb Hotel regularly. No one would dare be seen without proper accoutrements such as the hat then in vogue and the proper dress for the season at hand.

The administrative offices of the Kentucky Division of the Illinois Central Railroad were located at 1500 Kentucky Avenue. Frequently visitors from Chicago required a banquet at the Cobb. Women were few, usually telephone operators or clerical personnel. Division office personnel were still predominantly white males as late as the 1950s. Each desk sported its own spittoon that was emptied each morning by one of the two African-American porters.

Gus Hank Jr. was a captain during World War I. In France he rode Harley-Davidson motorcycles, serving as a special-dispatch rider. On occasion he bragged that he noticed a German airplane diving at him with the intent of strafing. Gus flattened himself on the frame and wrenched the throttle handle as far as it went, and he got away. The bike came home with Hank—the first in Paducah.

Mary Wheeler did while others talked. She went to France with the Red Cross in 1918 to entertain the troops. Later, she collected folk songs in Appalachia and later, Ohio riverboat work songs, which she published in Steamboatin’ Days: Folk Songs of the River Packet Era in 1944. Miss Mary earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and taught at various places including Paducah Junior College.

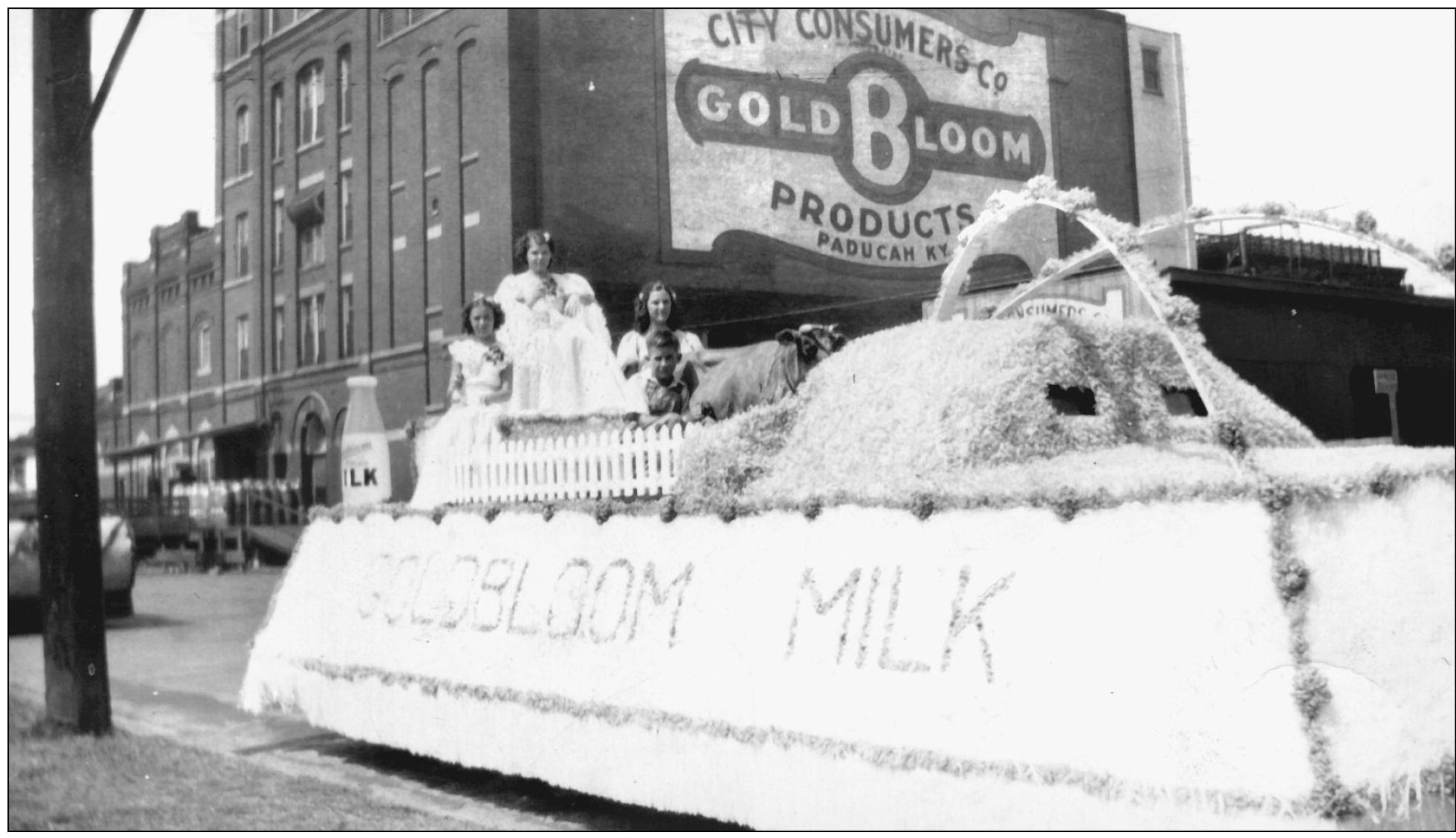

In 1913, E.J. Paxton Sr., editor of the local newspaper; W.F. Bradshaw, a banker; Con Craig, secretary of the Paducah Board of Trade; and W.E. Cochran and H.C. Rhodes, merchants, formed the McCracken County Strawberry Growers Association. Beginning in 1914 when half a carload was shipped out, strawberries played a major role in the economy of Paducah until the early 1950s. By 1935, the market contained nine counties and 5,000 members planting over 4,000 acres. That peak year 830 carloads of berries were shipped by rail from Paducah. Growers got $5.56 a crate prior to 1930. Starting in 1937 a festival celebrated the season, complete with a Strawberry Queen, marching bands, and several days of activities. World War II put a halt to the occasion for a time. It resumed in 1945 and lasted until 1948. This float by Goldbloom Dairy was typical of the entries. Anna Lou Shaffer French, Verna Jean Subblefield, an unidentified girl and boy, and a Jersey cow constituted the crew for the float.

The railroad shops of the Illinois Central were among the largest in the world when constructio began in 1925. The project moved Coleman Hill 16 miles away in McCracken County to us for fill. Completed in 1927, the facility built 20 of the 2,600 Mountain class 4–8–2 steam locomotives, identified by their extended capacity tender that allowed them to make the ru from Fulton to Woodstock, just outside Memphis, without taking water.

Originally Goldbloom Dairy used horses to deliver milk. These animals soon knew the routes better than some drivers. One had to persuade the horse otherwise when a patron changed their usual order. No matter how faithful, the horse could not compete with the advent of the gasoline-powered engine. Now exhaust changed Paducah’s streets—soon some noticed the reduced number of birds downtown.

In 1945, segregation denominated the composition of the armed forces. African-American soldiers often were assigned to menial tasks rather than integrated combat units. One example of this stereotyping was the “Red Ball Express” supply outfit that managed to keep up with the 3rd Army of George Patton in the race to the Rhine. President Harry S. Truman integrated the military by executive order in 1948.

Women made a significant contribution in World War II. Over 300,000 served in the army as nurses and the WAACs (Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps) that later became the WACs (Women’s Army Corp). The navy had its WAVEs (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services); there were women marines. Women enlisted in the SPARs (U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserves) and WASPs (Women Airforce Service Pilots). Twenty-five percent served overseas. In 1939 only 36 women worked in shipyards; in 1945 the number reached 200,000. “Rosie the Riveter” became a role model for women.

The traditional celebration of November 11 as the end of World War I took on greater meaning in 1945 as World War II finally came to an end in September with the surrender of the Japanese. A grateful people turned out in record numbers to commemorate the sacrifice of so many. Throughout the crowd were recent returnees with the “ruptured duck” badge signifying they were recently released from active duty.

The Carnegie Library in Paducah opened opportunities to explore the world through reading to the youth of Paducah and McCracken County. Special incentives, such as the event portrayed here, whetted the appetites of children to delve deeper into the rich heritage of the previous generations. Carnegie firmly believed that the secret to improving the lives of the workers in America was to make educational opportunities such as libraries available.