Blancan Land Mammal Age, 3.5 million years ago

The late Pliocene in North America was a time of transition. The animal communities that existed here shortly before the onset of ice ages were still spread across much of the continent, while at the same time many present-day species were making their first appearances. Thus the era was a fascinating mixture of ancient and modern animals—the fauna of North America looked familiar in many ways, but animals from earlier times still roamed the continent.

Most people would easily recognize many of the Pliocene fishes, amphibians, and birds of southern Idaho—the setting of this mural—as well as the contemporary species of beaver, muskrat, bear, puma, weasel, otter, and peccary, although not all of them live there today. Others were close relatives of modern species, including horses, pronghorn, and rabbits. But alongside these animals lived an array of animals now vanished from the continent’s landscapes: elephants, camels, ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats.

Although the Idaho location that Matternes reconstructed in this mural was wetter in the Pliocene than it is today, broad, forested valleys, modified by beaver dams, are still a common sight across the northern Rocky Mountain region. A similar pattern held true across much of North America: the ecosystems and landscapes of the Pliocene, for the most part, would seem familiar to our eyes, with some variations depending on local climate.

One of the richest late Pliocene fossil deposits in North America is found in the Glenns Ferry Formation, a rock layer that crops out in bluffs near the town of Hagerman in southern Idaho. Here the so-called Hagerman Horse Quarry—also known as the Gidley Quarry—was discovered in 1928. Curators James W. Gidley and C. Lewis Gazin excavated it over several subsequent seasons for the Smithsonian Institution. The quarry yielded dozens of specimens of a new species of horse, Plesippus shoshonensis (now known to represent a population of Equus simplicidens), including both male and female individuals of all ages.

Smithsonian researchers working under curator James W. Gidley excavate horse skeletons from the Hagerman Horse Quarry (with help from a modern horse), 1929 or 1930.

In addition, the quarry and nearby outcrops were rich with the fossils of many other animals, including rodents, carnivores, elephants, turtles, and birds. Together they provide a more complete picture of life on land at this moment in time than almost anywhere else on Earth. Plant fossils found here indicate that the surrounding land was largely open grassland, in which herds of large mammals could feed and thrive. Lakes and streams provided aquatic habitats for amphibians and fishes, as well as fresh water for terrestrial animals.

The Hagerman area was recognized as a National Natural Landmark in 1975, and in 1988, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument was officially created to preserve the region’s fossil wealth.

The museum began circulating the idea for this mural as early as 1964, when it would have concluded the Age of Mammals in North America exhibition. Next it was slated to form part of a triad of late Cenozoic murals for the new Hall of Quaternary Vertebrates, focusing on the time in which we still live today. Thanks to further change (see this page for more details), the mural actually served to introduce the exhibit Ice Age Mammals and the Emergence of Man. It was intended to show a setting in the northern Rocky Mountains about 3.5 million years ago, during the late Pliocene Epoch. Also called the Blancan Land Mammal Age, it spans the close of the Neogene Period and the very start of the Quaternary.

Matternes began his research for this mural in 1966, under the guidance of Smithsonian curator Clayton Ray, and traveled west to study the Glenns Ferry Formation outcrops in person. Once in Idaho, he discovered that he needed a credit card to rent a car; lacking one, he managed to convince the rental company to accept his Smithsonian contract (which he had brought along) instead.

The region’s geology provides evidence of abundant volcanism, but there was scientific disagreement about what forms this may have taken on the landscape, so Matternes chose to show only volcanic cinder cones in the background. He set the scene in the late afternoon to use the dramatic effects of lengthening shadows.

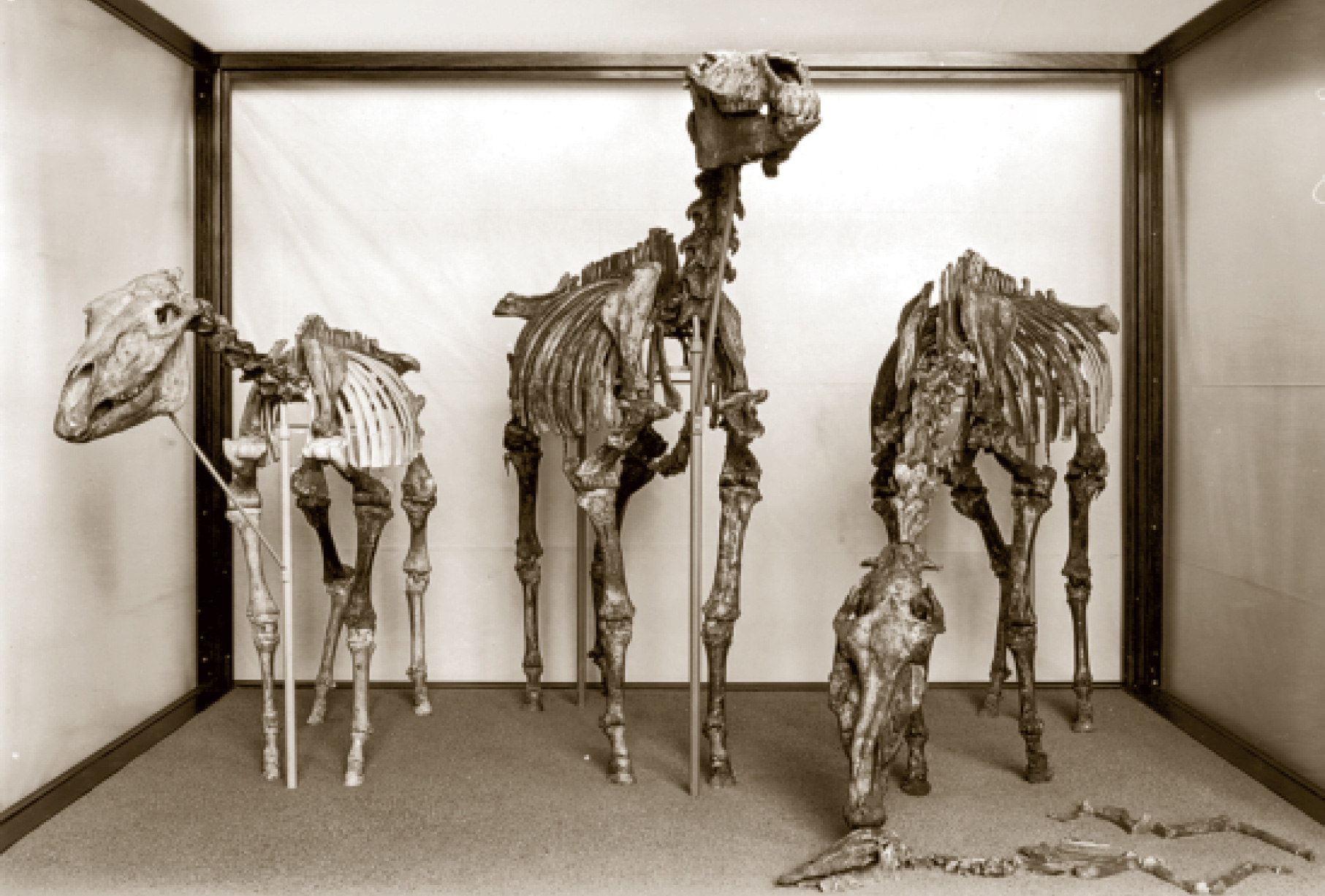

Three adult skeletons and one foal of the Hagerman horse, Plesippus shoshonensis (now referred to as Equus simplicidens), as they were prepared for display at the Smithsonian, sometime before 1963.

He first developed a full-color comprehensive sketch in 1967, and then transferred the image to the gallery wall by means of his grid system (see this page for more details). Although the exhibit was closed to the public while he worked, visitors sometimes passed through the hall uninvited, and Matternes occasionally would stop to discuss the mural’s contents and answer questions before directing the wayward museumgoers onward. By July 1969, he was more than halfway done, and he finished the mural by the close of that year.

Unusually among the murals, the Hagerman landscape includes a large number of non-mammalian species, including birds, a frog, and a catfish. The Glenns Ferry Formation had produced many small fossils of animals such as these, allowing the artist to create a richer portrayal of all aspects of the fauna. Clayton Ray’s interest in this broader assemblage of animals further drove their inclusion in the mural.

The exhibit associated with this mural featured a display of fossils that Gidley and Gazin had collected for the Smithsonian. One highlight was a group of four Hagerman horses, including the skeleton of a small foal. Most specimens were mammals, but the Hagerman turtle Pseudemys idahoensis was also displayed. Together they composed a virtual snapshot of the North American Pliocene, combining fossils drawn from a single ancient ecosystem with Matternes’s rich depiction of it in life.