Chadronian Land Mammal Age, 38.0 to 33.9 million years ago

North America’s climate began a long period of cooling and drying in the late Eocene, part of a set of broader worldwide changes occurring at the time. The world was still warmer than it is today, but a big global temperature drop occurred at the close of this epoch, and ice sheets began to form on Antarctica for the first time in the Cenozoic. One result of this cooling and drying trend was the appearance of open woodland environments across the North American continent and the loss of wet rainforests. This resulted in the extinction of rainforest mammals such as primates. Alligators—which had lived as far north as the Canadian Arctic in the early Eocene—were pushed far to the south by the cooling climate.

Mammal evolution began to produce species in lineages that still survive today, alongside archaic groups that left no living descendants. This mélange of old and new would tip increasingly in favor of the new as time went on. North America hosted early rhinos, tapirs, and horses, as well as pigs, camels, rabbits, rodents, cats, and dogs. But alongside them lived forms unknown today: hoofed mammals such as the giant brontotheres, horse-like hyracodont rhinoceroses, hippo-like anthracotheres, bizarre-horned protoceratids, and short-faced oreodonts—as well as archaic carnivores such as cat-like, saber-toothed nimravids and strong-jawed hyaenodonts. Most were eventually replaced by later lineages with modern descendants.

Mammalian fossils from the late Eocene are exceptionally abundant in the northern Great Plains, where the White River Group of geological strata is widespread. In the dry modern badlands of South Dakota, Wyoming, and Nebraska, it is possible to collect hundreds of fossils a day. Because many of these outcrops are along the Missouri River, early European explorers of the region soon encountered them. Some sent specimens back east to Philadelphia paleontologist Joseph Leidy, who described them between 1848 and 1853. Expeditions from Yale, Princeton, and the New York State Geological Survey soon followed.

The Charles Gilmore crew collecting a brontothere for the Smithsonian in Wyoming, 1931 or 1932.

Of course, these fossils already had been long known to the Pawnee and Lakota Sioux of the region. The Lakota described the remains of the great ancient mammals as Wakíƞyaƞ) (“thunder beasts” or “thunder beings”), entities that held marked cultural significance. This inspired Yale University’s Othniel C. Marsh to name some of them brontotheres (from the Greek for “thunder beasts”); they were also called titanotheres (“titanic beasts”). Subsequently, the infamous “Bone Wars” of the 1870s and 1880s played out in part here between Marsh and Edward D. Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, as the two scientists competed to find and name new species of these mammals.

Eventually, most major U.S. museums collected in these so-called Titanotherium Beds of the Great Plains, resulting in an exceptionally well-documented mammalian fauna for the region. Charles Gilmore led brontothere-collecting expeditions on behalf of the Smithsonian in the early 1930s. The Trigonias Quarry in Colorado, discovered in 1920 and excavated by the Colorado Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature and Science), produced dozens of skeletons of an early hornless rhinoceros, perhaps a herd, buried in volcanic sediments.

In 1867, the discovery of a late Eocene petrified forest composed of giant redwood (Sequoia) trunks at Florissant, high in the Colorado Rockies, provided the first evidence of the landscapes of this age. The site also included lake-bed deposits that had preserved delicate leaves, flowers, insects (including butterflies and caterpillars), fishes, and even birds and small mammals. Florissant gained international acclaim and scientific attention; in particular, Theodore Cockerell of the University of Colorado studied the insects, and Leo Lesquereux (a Swiss paleobotanist who consulted for U.S. state geological surveys) and Harry MacGinitie of the University of California, Berkeley, studied the plants. MacGinitie’s 1953 monograph on the flora is thought by many to be the start of modern paleobotany, as he not only described the fossils but also reconstructed the ancient ecosystems to which they belonged.

The 1960s exhibit The Age of Mammals in North America featured this display, “Skulls of Oligocene Mammals.” The diversity of species is illustrated with a variety of carnivore and herbivore skulls from the (now late Eocene) White River Group beds.

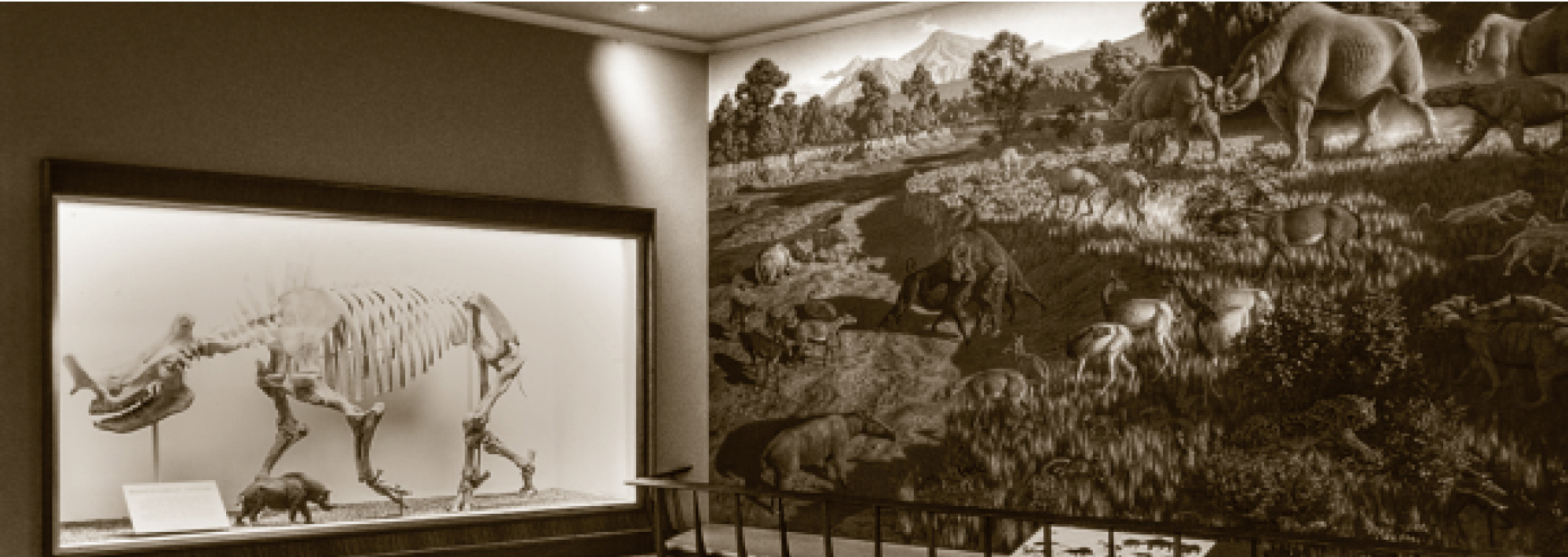

A skeleton of Brontotherium (now called Megacerops) alongside Matternes’s late Eocene mural in The Age of Mammals in North America, 1980.

The mural is set during the Chadronian Land Mammal Age. At the time Matternes created the painting, the Chadronian was thought to date to the beginning of the Oligocene Epoch, and so for many decades this work has been referred to as the “Oligocene mural.” But refined radiometric dating of Chadronian rocks has revealed that they date to the end of the Eocene Epoch (38.0 to 33.9 million years ago).

Matternes began developing sketches of the mammals in this mural in 1959, basing them on a species list provided by curator C. Lewis Gazin. Because he lacked good plant fossils from the immediate vicinity of the White River beds, the artist communicated extensively with MacGinitie and others to develop a suitable flora. As a result, he used the Florissant Fossil Beds as his basis even though the site was originally a high-elevation environment. Nonetheless Florissant was contemporaneous to the White River Group and included species that plausibly could have lived in the lower elevations represented by those beds.

He set the scene amid the long shadows of a late afternoon, recalling, “I did this after I had driven through the West, and I was just enthralled with the effects of light and of atmosphere. That was the inspiration, really, for the very low light source and the oblique light on each of these animals, which brings out very nicely their form.” Completed in 1962, this was the third mural he finished.

The Smithsonian’s collections, like those of many major U.S. museums, hold a rich assembly of late Eocene mammal fossils, many of which were placed on exhibition alongside this mural. A number of excellent skeletons highlighted the diversity of early perissodactyl mammals, while a selection of skulls from the White River beds illustrated a broad array of mammal groups. Much of Marsh’s brontothere collection had ended up with the Smithsonian, where it had become the focus of its own exhibit in the 1920s. The skeleton of the giant Megacerops was a particular prize among Marsh’s finds, and it was displayed along one wall of the bay that held the mural. It is still displayed in the same dynamic pose.