Alice, my mother’s third child, was a mistake. Rhoda did not want more children. Why should she? After two tries, she got her son, the Jewish prince she desired, in the gender she disapproved of. And four years later, in her forties, she became pregnant with Alice. It’s a less risky age today, much riskier then.

One day in the early sixties, at the V.A. hospital in the Bronx, after a visit with my father, who was recovering from his heart attack, Alice, my mother, and I were leaving. As we stood waiting for an elevator, my mother, to whom any male dressed in white was a figure of authority even if he turned out to be a porter, started chatting up a man in white who, for all I knew, might have been a pizza deliveryman. She said, “That’s my daughter over there, a wonderful woman. She raises two children, she teaches in school, she never stops. But three times a week she drives all the way in from Long Island to drive me from Queens, no less, up here to the Bronx for a visit to my husband in the veterans hospital. And she has never once complained about the inconvenience. Can you imagine? And just think, before she was born I tried to abort her.”

Alice and I stared at each other, text messaging “What the fuck?” with our eyes. My mother, who had hundreds of secrets we weren’t old enough to be told, had revealed to a complete stranger (because he wore white) a mind-boggling secret, stated so casually that if the two of us weren’t standing there, witness to what the other heard, we might not have believed our ears.

I shook my head at Alice and glared. The glare meant: “Do not, under any circumstances, respond. We will talk about this the second we escape from this maniac.”

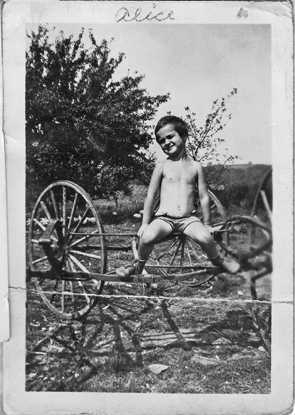

Her confession to the man in white explained a lot. Family photos from childhood documenting day trips, outings, family vacations were a puzzle to my sisters and me. There would be the three of us in drugstore-developed snapshots: caught in Central Park, the Bronx Zoo, up in Wappinger Falls at a two-week summer bungalow rental. Pictures of the three siblings posing with my mother, my father, assorted animals, dogs, a horse, a goat. And my mother fastidiously labeled, on the bottom of each picture or on the back, the subjects of the photograph. Repeatedly you might read, Jules, Mimi, Ma, Dad, goat, dog, horse, but year after year, picture after picture, the name seldom inscribed—the name aborted—was Alice’s.

But it was not that simple. My mother loved Alice. When she was an infant, my mother dubbed her “Lovey” because of her cuddly adorableness. She paid her as much attention and related as many anecdotes about her as she did about Mimi and me. She boasted about her gift for affection, her love for children, her babysitting skills at ten and eleven, boasted later about her daughter the college graduate, the social worker, the history teacher. “Can you imagine? How does she keep so much in her head? Doesn’t it give you a headache, Alice, all that thinking?”

At those times when she remembered her, she was proud of her youngest child. She doted to the extent she could (which was hardly at all) on Alice’s sons, Bruce and Glenn. The adult Alice was someone she took pride in, a successful teacher and mother, the only one of her children who was a college graduate; this Alice was a recognizable and certifiable entity. But the child Alice, named after Lewis Carroll’s immortal creation, stared out at us from early photographs with nothing for a mother to show off about. She was not a cartoonist like her big brother or a talented writer like her bigger sister. This may have left my mother nonplussed, challenged as to what to do with a child without artistic talent. What do you say about such an Alice? Not that much. Maybe it’s better to disappear her down a rabbit hole.

Because she was the child my mother overlooked, Alice grew up the least neurotic, married Hal, a musician and social worker from the other side of Stratford Avenue, the 1100 block, across the trolley tracks. They moved to East Meadow, Long Island, and then into a beautiful large home in Huntington. Alice taught American history for twenty years in the Island Trees district under the sway of a McCarthyite superintendent of schools whom my sister agitated against as a union activist.

Presently she is reminisced about on Web sites set up by former students as the teacher who meant the most to them and understood and addressed their problems when no one else bothered to try. Mrs. Korman. Thirty and forty years later, they chat online about my baby sister.

A good thing my mother let her live.

Lovey, 1939