Introduction

Pilsener is the dominant beer style in the world today. From Milwaukee to Brussels and Juarez to Manila, beers brewed in every part of the planet proudly bear the label “Pils” or “Pilsener,” a tribute to the city of Plzeň, Czechoslovakia, where this style originated more than one hundred and fifty years ago. Many brand names also reflect the style’s nation of origin: National Bohemian beer once was brewed in Pennsylvania, and today you can find on the shelves of American supermarkets Bohemia beer brewed in Mexico. To be sure, not all of these beers live up to their heritage. Many of those brewed in North America and the Orient are pallid imitations with only a superficial resemblance to the genuine Pils. Still, the very fact that so many brewers make a Pilsener-style product is testimony to the reputation of the Bohemian brewers and the impact their creation has had on the world of brewing.

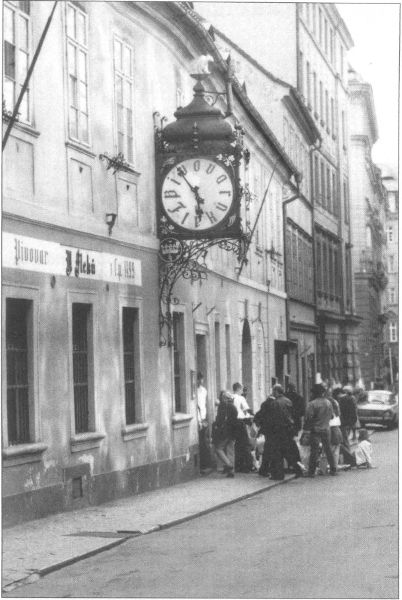

Prague’s first and most famous tavern, U Flecků, dates back to 1499 and brews its own beer.

Probably the best evidence of Pilsener’s appeal has been its influence on the brewing industry of Munich, where lager brewing originated. Munich’s proud tradition has been rooted in a very different style of beer—dark, sweet, aromatic Münchner. In the 1920s, when applied chemistry had advanced to the point where brewers could make both light-and dark-colored beers from the same water, the Munich brewers introduced a new style of Munich beer. The new beer was similar to the original but pale in color and obviously designed to compete with the Pilsener lagers that had gained so much popularity. Today this pale Münchner, often called Helles, is the everyday drink of Bavarians. The Munich breweries also have started making their own Pilseners, and world beer authority Michael Jackson was bemused to find the great Spaten brewery touting its Pilsener as “our best beer!”

I first became acquainted with genuine, European Pilsener in Hamburg, Germany, in 1971. I went into a restaurant and a waiter, assuming that I was American and would want a light-colored beer, asked if I wanted Pilsener. “Ja,” I answered, not really sure what he meant or even why he was asking the question. Weren’t all beers Pilseners?

I don’t believe I had ever tasted a European lager before, and that one was a revelation. Presented in the classic, tall, conical Pilsener glass, the beer had a depth of flavor I had never encountered. The stinging, flowery hop aroma was an enticing prelude to the rich, malty sweetness of the flavor, which was perfectly balanced by its bitterness. I drained the first one and ordered a second. Eighteen years later, I still credit that German Pilsener as the beginning of my serious involvement with the brewer’s art.

I still feel a special affection for a good Pilsener, and with the passage of time I appreciate its virtues even more. It is light without being insipid or bland; hoppy, yet smooth and mellow. It is simultaneously refreshing and immensely satisfying—two characteristics that may seem to be mutually exclusive and that are not, in my opinion, so successfully combined in any other beer style. At the same time, Pilsener is not a “big” or “complex” brew that brims with esters and other fermentation byproducts. It has a clean, simple flavor profile that makes it an ideal accompaniment for many types of food. It is a drink for all occasions, and I believe it is this adaptability that has made it the most popular beer today in the nations of Northern and Central Europe.