SALLY BENSON

By eight o’clock in the morning, the boys in Room 1-B had almost finished trimming the Christmas tree they had bought for Mr. Parsons. Every master in St. Benedict’s School, in the East Eighties, had his own tree, and although it was an established custom and not a surprise at all, the boys made a practice of hiding the trees on the roof and getting to school as early as six in the morning on the last day before the holidays, so as to have the trees set up and trimmed before the masters arrived. This year, Cecil Warren had been in charge of the Tree Fund and the Decoration Fund for 1-B, not because he was popular but because it was generally agreed that he was very good at getting money out of people. He was ruthless about it. He didn’t even mind mentioning money, although the other boys at St. Benedict’s understood that money was something to be mentioned carelessly, if at all. He came right out and called it money, or cash, or dough, and the way he said it made the other boys feel uncomfortable. It was like calling a boy by his first name. St. Benedict’s boys were never called by their first names.

Warren had set about collecting the money in a businesslike manner. He had made an alphabetical list of the boys’ names and, by dunning them, had collected a dollar from every boy in the class, a total of fifteen dollars. His method had been painful, but it was generally agreed that the result was nothing short of magnificent, as the 1-B tree was the largest and most expensive one to be carried down from the roof that morning. In fact, it was so much handsomer than the other trees that Lockwood and Brewster even wondered if it wasn’t too fine. Lockwood and Brewster were the committee in charge of buying the tree and the decorations. Lockwood had flawless taste, and Brewster was strong enough to carry the tree up the four flights to the roof, carry it down again to the classroom, and set it up on the stand in the corner by the blackboard. Its branches sagging under the weight of ornaments, tinsel, and lights, the tree seemed—to Lockwood, at least—a trifle ostentatious. He stepped back and looked at it. “Well, there it is,” he said. “You don’t think it’s too…”

“I know what you mean,” Brewster said quickly. “I was sort of thinking the same thing myself.”

“Precisely,” Lockwood said. “It doesn’t seem quite—well, you know—to have Mr. Parsons have a larger tree than Captain Foster.” Captain Foster was the headmaster.

“Of course, it’s Mr. Parsons’ first Christmas here, and that might sort of explain it away,” Brewster said.

Lockwood looked pained. “The very reason,” he said, “not to make anything special of it. I mean to say it must be rather grim for him anyway.”

Warren, who had not helped with the decorating, laughed. “It’s his first Christmas all right,” he said. “Maybe it’ll be his last. Could be.”

Lockwood and Brewster turned and stared at him coldly. “All right, Warren,” Lockwood said quietly. “You did a good job and we’re duly grateful, but you’ve said enough.”

“Could be,” Warren repeated stubbornly. “Could be that he’d go back to jolly old England.” He fumbled in his coat pocket and brought out a small black book, which he opened. “And by the way, Lockwood, you owe me fifty cents for comic sheets.”

Earlier in the year, Warren had cornered the comic-sheet market at St. Benedict’s. He bought the Sunday papers every week and then rented the comic sheets from them to the boys to read, at five cents each.

Lockwood took two quarters from his pocket and tossed them on Mr. Parsons’ desk. Warren picked them up deliberately, checked the amount off in his black book, and spoke. “Pope—” he began.

“If you have any more business to attend to,” Lockwood said, “will you mind putting it off until later?” His voice was finely sarcastic and Brewster glanced at him admiringly.

“And now,” Lockwood went on, “we’d better get on with the presents.”

The boys rushed toward the coatroom and came out again carrying packages, which they placed on Mr. Parsons’ desk. The room looked bright and cheerful, with the red, white, and green packages covering the brown desk blotter. There were wreaths at the three windows, and the blackboard was covered with sprays of holly and a Santa Claus drawn with colored chalk.

Warren walked to his desk and began arranging the stamps in his collection. He had a fine collection, with duplicates which he sold or traded. His desk was in the front of the room, and when a boy was sent to the blackboard to write, Warren would hold out his hand, palm up, with a stamp in it, to show it. He would hold his hand low, so that Mr. Parsons couldn’t see him. Now he pretended not to see that the other boys were getting ready to walk to chapel. He sat still as they filed out, and then he got up and went over to Mr. Parsons’ desk. He took his present for the master from his pocket and laid it on top of a large package wrapped in red-and-gold paper and tied with wide green ribbon. Then he ran out of the room.

Chapel was at eight-thirty, and it was held in the large hall on the first floor. Captain Foster was seated in the center of the platform, with Mr. Gaines and Mr. Martin, who had been at the school the longest, seated on either side of him. Mr. Parsons sat at one end of the row. He was a thin man in his early thirties, and his hair, his skin, and his tweed suit were the color of dust. He wore a sprig of holly in his buttonhole, and as his class filed in, he smiled down at them. The 1-A boys and the 1-B boys sat in the front rows, as they were the class that would graduate in the spring, and they sat quietly and didn’t fidget in their seats, as the younger boys did.

Captain Foster waited until all the boys were settled, and then he nodded to Mr. Howard, who taught music and played the organ, and the school rose to sing the St. Benedict’s Christmas hymn. The boys’ voices were high and clear.

“Christmas is nighing. Hark!” they sang.

Mr. Parsons sang with them. He had learned the hymn the night before. The hymn, Captain Foster had explained to him, was, like the St. Benedict’s school song, “very dear to us all,” and by that Mr. Parsons understood that he was supposed to learn it by heart. It was not a very good hymn, but as he stood on the platform singing it, looking down at his boys, Mr. Parsons almost felt at home. His shoulders relaxed and the color came to his face. “Upon this holy night,” he sang. And then, as the hymn ended, he bowed his head for the Lord’s Prayer. With his head bowed, he could see where his sleeve was frayed, and he thought that he must do something about a new suit. It was quite all right to look comfortably shabby, but his suit was a step beyond that, and once he knew where he stood, he would feel justified in getting a few things for himself. Not that he hadn’t understood Captain Foster’s point when he explained that it was a question of getting the boys to like you, getting their confidence. In a school like St. Benedict’s, you had to get the boys to like you, because boys had a way of complaining to their parents, and if the parents weren’t satisfied—well, there was no school. “Of course,” Captain Foster had said, “we can only give up to a point. But we do have to see eye to eye with the boys and their parents up to that point.”

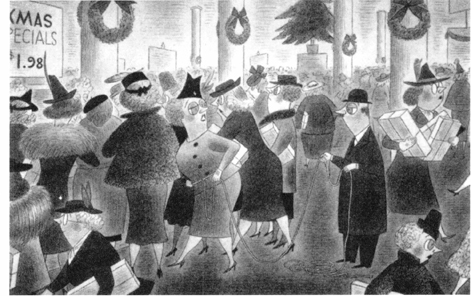

CHRISTMAS RUSH

Dropping in at the main Post Office to see how business was a week before the deadline for soldiers’ Christmas presents, we found the staff in a light perspiration. The man who took us around, a Mr. Gillen, said that since September 15th they had handled some four million parcels with APO addresses and that the last-minute rush was sure to be something fierce. Many of the temporary helpers are high-school students, who are of no great help in a Christmas log jam. “We have spiral parcel chutes in the building, and the kids keep running up to the fifth floor and sliding down,” Mr. Gillen told us wearily. The real worry at the Post Office, though, is improperly wrapped or addressed parcels. Improperly wrapped parcels are handled by the “reconstruction department,” which has now been built up to fifty men working three overlapping shifts of twelve hours a day. Between them they do what they can for the day’s intake of flimsy parcels, which averages about eight thousand.

If a package has merely softened up enroute, it’s just a matter of cutting off the address, rewrapping the contents in brown paper, and pasting the address on the new package. An experienced man can handle twenty such packages an hour. A really insoluble problem is the gummed address label of the “To——From——” type. Some people just don’t use enough spit, the label drops off, and the anonymous package winds up six months later at a public auction. “There’s going to be some mighty disappointed guys this Christmas,” Gillen predicted. In general, the wrapping jobs done by the stores are good, Gillen told us. He had a word of special commendation for Schrafft’s. “Can’t budge their packages,” he said. The Post Office gets a good many lunches in smashed shoe boxes, which would have been contraband anyhow under the rules for mailing food. Most of them are mailed by people with R.F.D. addresses and no sense of geography. Naïve addresses are not uncommon. We peeped over one postal man’s shoulder and found that he was puzzling over a box of candy addressed to “Richard F——, Infantry, U.S. Army. Overseas.” “By the time I go off work, I’m wondering just what goes on in people’s heads,” he muttered to us.

A good many packages simply disintegrate, and it’s impossible ever to tell which article goes in which package, let alone where the packages were intended to go. The contents of such packages are piled in crates and are sold at auction unless they are claimed within six months by the senders. In one salvage crate, we saw chewing gum, a bologna sausage, soap, an electric shaver, tobacco and cigarettes, and bath powder. We remarked that it all resulted in rather a heady aroma, and one of the wrappers said we should of been there yesterday. “We had four fried chickens,” he said. “From San Francisco.” Judging by the smashed packages, there’s a good deal of contraband going overseas—beer, wine, whiskey, and lighter fluid, all expressly banned. Most of the booze is spilled even before it gets to the post office. “We had a broken bottle of imported Scotch here yesterday,” a wrapper told us. “I could of wept.” That day’s prize package, so to speak, was one which, when opened for rewrapping, was found to contain a wristwatch, a Colt .45, and a box of chocolate-covered cherries.

—ROSANN SMITH, WILLIAM KINKEAD,

AND RUSSELL MALONEY, 1943

Mr. Parsons lifted his head at the end of the Lord’s Prayer and sat down with the others as Captain Foster began to address the school. He wondered if he had tried to see eye to eye with Warren when reporting Warren’s stamp dealings and the little matter of the comic sections to Captain Foster. Not that he minded the boys’ trading things—it was a natural thing to do—but there was something about the way Warren did it. He looked down and his eyes found Warren. Warren was staring at Captain Foster, and suddenly Mr. Parsons heard what Captain Foster was saying.

“… and a certain boy who has been trading in stamps and has managed to get a monopoly on comic strips, which he peddles during school hours…” Captain Foster said.

It was all Mr. Parsons could do to keep from interrupting Captain Foster to tell him that it was a matter of no consequence and that he’d mentioned it to him only to ask his advice, certainly not to have it dragged out in front of the whole school. He looked back at Warren to see how he was taking it, and he saw that Warren was smiling a little, and suddenly Warren’s eyes met his in a way that made him uneasy. He was glad when Captain Foster left Warren and went on to the matter of water pistols and the unsportsmanlike behavior of some of the boys during a football game.

When the school rose once more, to sing the St. Benedict’s Alma Mater, Mr. Parsons relaxed again. He was glad he had not told Captain Foster about the loaded dice Warren had made in manual-training class, and when the exercises were over, he stopped to say a word to Captain Foster about the boy.

“Captain Foster,” he said, “I’m glad you didn’t mention the boy’s name.”

“We never do,” Captain Foster said. “We merely bring such matters up, lay them on the board, and start off the new year with a clean slate.”

“I see,” Mr. Parsons said. “I’m sure the boy means no harm. He’s a clever boy, does well in his studies, and I don’t think I should have mentioned it at all if he hadn’t proved himself to be so distracting to the rest of the class. There’s nothing wrong with the boy.” He swallowed, and his hand went up to the sprig of holly in his buttonhole. After all, he thought, it is Christmas. “The fact is,” he went on, “I like the boy.” Then he nodded brightly to Captain Foster and hurried out of the hall.

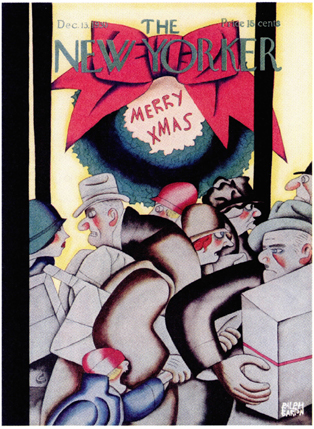

Mr. Parsons almost bounded up the flight of stairs that led to his own classroom, and when he opened the door and saw the tree shining with lights and saw the boys, who were waiting for him expectantly, he called out to them, “Merry Christmas! Merry Christmas!”

“When I jerk twice, pull as hard as you can.”

He walked toward them as they stood grouped around his desk, nervously waiting for him to open his packages. “Merry Christmas, sir,” they said.

He looked down at his desk, and the sight of the packages tied with bright ribbons warmed him. “Well, what’s this?” he asked.

“Christmas, sir,” Lockwood said.

“It looks like Christmas,” Mr. Parsons said. “Even to the fine tree. I think I’ll have to take that tree home with me.”

“Why not?” Brewster said. “I’ll help you carry it.”

The boys laughed appreciatively. “Open your presents, sir,” Pope said.

Mr. Parsons reached for a package, carefully untied the ribbon, and opened it. It was a bottle of whiskey from Brewster, and the boys screamed with laughter. Mr. Parsons read the label and held the bottle up to the light. “Too bad to waste it,” he said, “so I suppose I’ll have to drink a little of it—later.”

He picked up another package and opened it. “A cigarette lighter,” he called out. “From Pope!”

He pressed on the lighter and it worked, and the boys cheered. Mr. Parsons looked down at the table and picked up an envelope. Inside the envelope was a card. “From Warren,” Mr. Parsons read, and, feeling inside the envelope, his fingers felt a smaller envelope. As he felt it, he knew what was in it. He took it out and slipped it into his pocket.

“What is it, sir?” Brewster asked.

Mr. Parsons’ hand held the envelope in his pocket. It was the small kind that people hand to doormen and janitors.

“It’s money,” Warren said. “Five dollars.”

The boys glanced uneasily at one another and the room grew still. Someone jostled the tree and needles fell to the bare floor with a dry, cold sound. Mr. Parsons looked at Warren, and he knew that the boys were waiting for him to help them out. He took the envelope from his pocket, opened it, and held the five dollars so that they all could see it, and then he laid it with the other presents on the desk. When he spoke, his voice was without expression. “Thank you very much, old man,” he said.

1946