JOHN UPDIKE

How strange it is—gut-wrenchingly strange—to realize that your parents, in a snapshot taken by memory, are younger not only than you now but than your own children. If I was seven or eight on a certain Christmas that I remember, my father would have been thirty-nine or forty, and my mother thirty-five or six. A couple of kids, really, living in her parents’ house with their only child, in a Depression that war’s excitement and mounting public debt hadn’t yet lifted. The taste of Christmas in the little Pennsylvania town of Shillington—one of the more penetrating in my life’s bolted meals—was compounded of chocolate-flavored piety, as sweetly standardized as Hershey’s Kisses, and a tart, refreshed awareness of where one stood on the socioeconomic scale.

Since at that latitude white Christmases were a rarity, the proper atmosphere had to be created within the front parlor: an evergreen tree more or less richly laden with decorations brought down from the attic; beneath the tree a “Christmas yard,” a miniature landscape of cotton snow and mirror ponds and encircling railroad tracks; a heap of wrapped presents, which at my age of seven or eight had not yet quite shed the possibility, like a glaze, that an omniscient, fast-moving Santa Claus had personally deposited them. Though we had the tree, our neighbors’ trees were in my impression bushier, pressing against the ceiling and crowding the front windows, and more sumptuously hung with reflective balls, colored lights, and glittering tinsel. We didn’t bother with tinsel; my mother, I believe, found it vulgar and messy. Though we had the yard, with a lovable blue Lionel train—engine, coal car, and two or three passenger cars, going around and around in tooting obedience to a cubic black transformer—friends of mine, or friends of theirs, had entire basements dedicated to mountainous, suburbanized mazes of tracks, switchoffs, tunnels, and toy stations. Our yard had a single tunnel, through a papier-mâché mountain whose snowy crest was approached up green-sprayed sides diagonally dented by what I understood to be sheep paths. Our pond was square, and any illusion of landscape fomented by the toy cows and cottages on its cotton banks clashed with the reality of my own huge, freckled face looking up from it when I peeked in. Though we had the presents, they seemed less numerous and luxurious than presents bestowed up and down Philadelphia Avenue, in houses externally more modest than ours.

Is there a professional friend or associate for whom it is always difficult to select a suitable nonpersonal Christmas gift? Here’s one suggestion that will answer the problem for you—give him a copy of the 20 Year Index to Sewage Works Journal.

—Adv. in the Sewage Works Journal

It’s as good as done

1951

On the Christmas that I painfully remember, one of the presents was a double deck of playing cards in a pretty box, whose gray surface had a fuzzy texture, and whose paper drawer was pulled out by a silken tab. I had unwrapped the box and had assumed that it was for me until my father’s voice, which was almost never raised to me in disapproval or correction, gently floated down from above with the suggestion that the cards were a present from him to my mother. This made sense: one of her habits—the most alarming habit she had, indeed—was to play solitaire at night at the dining table, under the stained-glass chandelier. “The weary gambler,” she would intone theatrically, “stakes her all,” as she doggedly laid out the cards in their rows. Now her voice descended to me, saying that the cards were for all of us to share; and it was true, we did play cards, three-handed pinochle, and the box said “PINOCHLE” on it. Nevertheless, I was humiliated, as deeply as only a child can be, to be caught trying to appropriate her present. At the same time, I thought that if there had been more presents I would not have made such a mistake. And I was afflicted by the paltriness of this present from my father to his wife. At least, I am afflicted now, or have been the hundreds or thousands of times I have remembered this incident. The something pathetic about our Christmases, the something that strived and failed to live up to Shillington’s Noël ideal, was bared; a pang went through me that dyed the moment indelibly.

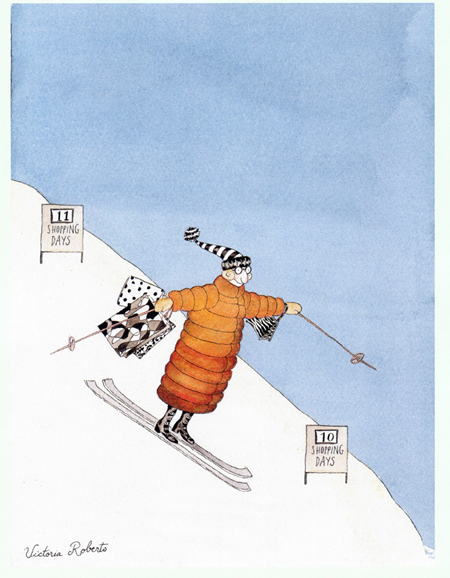

Some elemental, mournful triangle seems sketched: my grandparents, those distant, grave, friendly adjuncts, are absent from the room as I remember it. My parents are above me, the presents shorn of wrapping are around me, the three-rail Lionel tracks are by my knees, the tree with its resiny scent presses close. I have no memory of what I did receive that Christmas—the wooden skis, perhaps, with leather-strap bindings that never held, or a shiny children’s classic that would stay unread. I feel, for a moment, the triangle flip: through the little velvety box of cards I see my parents in their poverty, their useless gentility, their unspoken plight of homelessness, their clinging to each other through such tokens, and through me. I become in my memory their parent, looking down and precociously grieving for them.

Captured in this recollection, I want to look out the window for relief, at the vacant lot next to our house, at the row houses opposite. If there was no white Christmas, there was at least a public Christmas, a free ten-o’clock cartoon show at the Shillington movie theatre, followed by a throng of us children lining up at the town hall to receive a box of chocolates from the hands of Sam Reich, the fat one of the three town policemen. I remember eating these chocolates, trying to avoid the ones with cherries at their centers, while walking up Philadelphia Avenue with the other children as they noisily boasted of their presents—I seeming to be, as one sometimes is in a dream, tongue-tied.

1997