RICHARD FORD

Faith is not driving them, her mother, Esther, is. In the car it’s the five of them. The family. On their way to Snow Mountain Highlands—Sandusky, Ohio, to northern Michigan—to ski. It’s Christmas, or nearly. No one wants to spend Christmas alone.

The five include Faith, who’s the motion picture lawyer, arrived from California; her mother, who’s sixty-four and who’s thoughtfully volunteered to drive. Roger, Faith’s sister’s husband, a guidance counsellor at Sandusky J.F.K. And Roger’s two girls: Jane and Marjorie, ages eight and six. Daisy, the girls’ mom, Faith’s younger sister, Roger’s estranged wife, is a presence but not along. She is in rehab in a large Midwestern city that is not Chicago or Detroit.

Outside, beyond a long, treeless expanse of frozen white winterscape, Lake Michigan suddenly becomes visible. It is pale blue with a thin fog hovering just above its metallic surface. The girls are chatting chirpily in the back seat. Roger is beside them reading Skier magazine. No one is arguing.

Florida would’ve been a much nicer holiday alternative, Faith thinks. Epcot for the girls. The Space Center. Satellite Beach. Fresh fish. The ocean. She is paying for everything and does not even like to ski. But it has been a hard year for everyone, and someone has had to take charge. If they’d all gone to Florida, she’d have ended up broke.

Her basic character strength, Faith believes, watching what seems to be a nuclear power plant coming up on the left, is the feature that makes her a first-rate lawyer: an undeterrable willingness to see things as capable of being made better. If someone at the studio, a V.P. in marketing, for example, wishes a quick exit from a totally binding yet surprisingly uncomfortable obligation—say, a legal contract—then Faith’s your girl. Faith the doer. Your very own optimist. Faith the blond beauty with smarts. A client’s dream with great tits. Her own tits. Just give her a day on your problem.

Her sister is a perfect case in point. Daisy has been able to admit her serious methamphetamine problems, but only after her biker boyfriend, Vince, has been made a guest of the State of Ohio. And here Faith has had a role to play, beginning with phone calls, then attorneys, a restraining order, then later the state police and handcuffs. Going through Daisy’s apartment with their mother, in search of clothes Daisy could wear with dignity into rehab, Faith found dildos; six, in all—one, for some reason, under the kitchen sink. These she put into a black plastic grocery bag and left in the neighbor’s street garbage just so her mother wouldn’t know. Her mother is up-to-date, she feels, but not necessarily interested in dildos. For Daisy’s going-in outfit they decided on a dark jersey shift and some new white Adidas.

The downside on the character issue, Faith understands, is the fact that, at almost thirty-seven, nothing’s particularly solid in her life. She is very patient (with assholes), very ready to forgive (assholes), very good to help behind the scenes (with assholes). Her glass is always half full. Stand and ameliorate, her motto. Anticipate change. The skills of the law once again only partly in synch with the requirements of life.

A tall silver smokestack with blinking silver lights on top and several gray megaphone-shaped cooling pots around it all come into view on the frozen lakefront. Dense chalky smoke drifts out the top of each.

“What’s that big thing?” Jane or possibly Marjorie says, peering out the back-seat window. It is too warm in the cranberry-colored Suburban Faith rented at the Cleveland airport, plus the girls are chewing watermelon-smelling gum. Everyone could get carsick.

“This one’s from you know who, so make a fuss and thank him.”

“That’s a rocket ship ready to blast off to outer space. Would you girls like to hitch a ride on it?” Roger says. Roger, the brother-in-law, is the friendly-funny neighbor in a family sitcom, although he isn’t funny. He is small and blandly not-quite-handsome and wears a brush cut and black horn-rimmed glasses. And he is loathsome—though only in subtle ways, like TV actors Faith has known. He is also thirty-seven and likes pastel cardigans and suède shoes. Faith has noticed he is, oddly enough, quite tanned.

“It is not a rocket ship,” Jane, the older child, says and puts her forehead to the foggy window then pulls back and considers the smudge mark she’s left.

“It’s a pickle,” Marjorie says.

“And shut up,” Jane says. “That’s a nasty expression.”

“It isn’t,” Marjorie says.

“Is that a new word your mother taught you?” Roger asks and smirks. “I bet it is. That’ll be her legacy.” On the cover of Skier is a photograph of Alberto Tomba wearing an electric-red outfit, running the giant slalom at Kitzbühel. The headline says, “GOING TO EXTREMES.”

“It better not be,” Faith’s mother says from behind the wheel. Faith’s mother is unusually thin. Over the years she has actually shrunk from a regular, plump size 12 to the point that she now swims inside her clothes, and, on occasion, can resemble a species of testy bird. There are problems with her veins and her digestion. But nothing is medically wrong. She eats.

“And don’t forget—make it look like an accident.”

“It’s an atom plant where they make electricity,” Faith says, and smiles back approvingly at the nieces, who are staring out the car window, losing interest. “We use it to heat our houses.”

“We don’t like that kind of heat, though,” Faith’s mother says. Her seat is pushed up, seemingly to accommodate her diminished size. Even her seat belt hangs on her. Esther was once a science teacher and has been Green since before it was chic.

“Why not?” Jane says.

“Don’t you girls learn anything in school?” Roger says, flipping pages in his Skier.

“Their father could always instruct them,” Esther says. “He’s in education.”

“Guidance,” Roger says. “But touché.”

“What’s ‘touché’?” Jane says and wrinkles her nose.

“It’s a term used in fencing,” Faith says. She likes both little girls immensely, would like to punish Roger for ever speaking sarcastically to them.

“What’s fencing?” Marjorie asks.

“It’s a town in Michigan where they make fences,” Roger says. “Fencing, Michigan. It’s near Lansing.”

“No, it’s not,” Faith says.

“Then, you tell them,” Roger says. “You know everything. You’re the lawyer.”

“It’s a game you play with swords,” Faith says. “Only no one gets killed or hurt.” In every way, she despises Roger and wishes he’d stayed in Sandusky. Though she couldn’t bring the girls without him. Letting her pay for everything is Roger’s way of saying thanks.

“Now, all your lives you’ll remember where you heard fencing explained first and by whom,” Roger says in a nice-nasty voice. “When you’re at Harvard—”

“You didn’t know,” Jane says.

“That’s wrong. I did know. I absolutely knew,” Roger says. “I was just having some fun. Christmas is a fun time.”

Faith’s love life has not been going well. She has always wanted children-with-marriage, but neither of these things has quite happened. Either the men she’s liked haven’t liked children, or else the men who’ve loved her and wanted to give her all she longed for haven’t seemed worth it. Practicing law for a movie studio has accordingly become extremely engrossing. Time has gone by. A series of mostly courteous men has entered but then departed, all for one reason or another unworkable: married, frightened, divorced, all three together. Lucky is how she has chiefly seen herself. She goes to the gym every day, leases an expensive car, lives alone at the beach in a rental owned by an ex-teen-age movie star who is a friend’s brother and has H.I.V. A deal.

Late last spring she met a man. A stock-market hotsy-totsy with a house on Block Island. Jack. Jack flew to Block Island from the city in his own plane, had never been married at age roughly forty-six. She flew out a few times with him, met his stern-looking sisters, the pretty, social mom. There was a big blue rambling beach house facing the sea. Rose hedges, sandy pathways to secret dunes where you could swim naked—something she especially liked, though the sisters were astounded. The father was there, but was sick and would soon die, so that things were generally on hold. Jack did beaucoup business in London. Money was not a problem. Maybe when the father departed they could be married, Jack had almost suggested. But until then she could travel with him whenever she could get away. Scale back a little on the expectation side. He wanted children, would get to California often. It could work.

One night a woman called. Greta she said her name was. Greta was in love with Jack. She and Jack had had a fight, but Jack still loved her. It turned out Greta had pictures of Faith and Jack in New York together. Who knew who took them? A little bird. One was a picture of Faith and Jack exiting Jack’s apartment building. Another was of Jack helping Faith out of a yellow taxi. One was of Faith, all alone, at the Park Avenue Café, eating seared swordfish. One was of Jack and Faith kissing in the front seat of an unrecognizable car—also in New York.

Jack liked particular kinds of sex in very particular kinds of ways, Greta said. She guessed Faith knew all about that by now. But “best not to make long-range plans” was somehow the message.

When asked, Jack conceded there was a problem. But he would solve it. Tout de suite (though he was preoccupied with his father’s approaching death). Jack was a tall, smooth-faced, handsome man with a shock of lustrous, mahogany-colored hair. Like a clothing model. He smiled, and everyone felt better. He’d gone to Harvard, played squash, rowed, debated, looked good in a brown suit and oldish shoes. He was trustworthy. It still seemed workable.

But Greta called more times. She sent pictures of herself and Jack together. Recent pictures, since Faith had come on board. It was harder than he thought to get untangled, Jack admitted. Faith would need to be patient. Greta was someone he’d once “cared about very much.” Might’ve even married. But she had problems, yes. And he wouldn’t just throw her over. He wasn’t that kind of man, something she, Faith, would be glad about in the long run. Meanwhile there was his sick father. The patriarch. And his mother. And the sisters.

That had been plenty.

Snow Mountain Highlands is a small ski resort, but nice. Family, not flash. Faith’s mother found it as a “Holiday Getaway” in the Sandusky Pennysaver. The getaway involves a condo, weekend lift tickets, coupons for three days of Swedish smorgasbord in the Bavarian-style inn. Although the deal is for two people only. The rest have to pay. Faith will sleep with her mother in the “Master Suite.” Roger can share the twin bedroom with the girls.

When Faith’s sister Daisy began to be interested in Vince the biker, Roger had simply “receded.” Her and Roger’s sex life had lost its effervescence, Daisy confided. They had started life as a model couple in a suburb of Sandusky, but eventually—after some time and two kids—happiness ended and Daisy had been won over by Vince, who did amphetamines and, more significantly, sold them. That—Vince’s arrival—was when sex had gotten really good, Daisy said. Faith silently believes Daisy envied her movie connections and movie life and her Jaguar convertible, and basically threw her life away (at least until rehab) as a way of simulating Faith’s—only with a biker. Eventually Daisy left home and gained forty-five pounds on a body that was already voluptuous, if short. Last summer, at the beach at Middle Bass Island, Daisy in a rage actually punched Faith in the chest when she suggested that Daisy might lose some weight, ditch Vince, and consider coming home. “I’m not like you,” Daisy screamed, right out on the sand. “I fuck for pleasure. Not for business.” Then she’d waddled into the tepid surf of Lake Erie, wearing a pink one-piece that boasted a frilly skirtlet. By then, Roger had the girls, courtesy of a court order.

Faith has had a sauna and is now thinking about phoning Jack wherever Jack is. Block Island. New York. London. She has no particular message to leave. Later she plans to go cross-country skiing under the moonlight. Just to be a full participant. Set a good example. For this she has brought her L.A. purchases: loden knickers, a green-brown-and-red sweater made in the Himalayas, and socks from Norway. No way does she plan to get cold.

In the living room her mother is having a glass of red wine and playing solitaire with two decks by the big picture window that looks down toward the crowded ski slope and ice rink. Roger is there on the bunny slope with Jane and Marjorie, but it’s impossible to distinguish them. Red suits. Yellow suits. Lots of dads with kids. All of it soundless.

Her mother plays cards at high speed, flipping cards and snapping them down as if she hates the game and wants it to be over. Her eyes are intent. She has put on a cream-colored neck brace. (The tension of driving has aggravated an old work-related injury.) And she is now wearing a Hawaii-print orange muumuu, which engulfs her. How long, Faith wonders, has her mother been shrinking? Twenty years, at least. Since Faith’s father kicked the bucket.

“Maybe I’ll go to Europe,” her mother says, flicking cards ferociously with bony fingers. “That’d be adventurous, wouldn’t it?”

Faith is at the window observing the expert slope. Smooth, wide pastures of snow framed by copses of beautiful spruces. Several skiers are zigzagging their way down, doing their best to be stylish. Years ago she came here with her high-school boyfriend. Eddie, a.k.a. Fast Eddie, which in some ways he was. Neither of them liked to ski, nor did they get out of bed to try. Now skiing reminds her of golf—a golf course made of snow.

“Maybe I’d take the girls out of school and treat us all to Venice,” Esther goes on. “I’m sure Roger would be relieved.”

Faith has spotted Roger and the girls on the bunny slope. Blue, green, yellow suits, respectively. Roger is pointing, giving detailed instructions to his daughters about ski etiquette. Just like any dad. She thinks she sees him laughing. It is hard to think of Roger as an average parent.

“They’re too young for Venice,” Faith says. From outside, she hears the rasp of a snow shovel and muffled voices.

“I’ll take you, then,” her mother says. “When Daisy clears rehab we can all three take in Europe. I always planned that.”

Faith likes her mother. Her mother is no fool, yet still seeks ways to be generous. But Faith cannot complete a picture that includes herself, her diminished mother, and Daisy on the Champs-Élysées or the Grand Canal. “That’s a nice idea,” Faith says. She is standing beside her mother’s chair, looking down at the top of her head. Her mother’s head is small. Its hair is dark gray and not especially clean, but short and sparse. She has affected a very wide part straight down the middle. Her mother looks like a homeless woman, only with a neck brace.

“I was reading what it takes to get to a hundred,” Esther says, neatening the cards on the glass tabletop in front of her. Faith has begun thinking of Jack again and what a peculiar species of creep he is. Jack Matthews still wears the Lobb captoe shoes he had made for him in college. Ugly, pretentious English shoes. “You have to be physically active,” her mother continues. “You have to be an optimist, which I am. You have to stay interested in things, which I more or less do. And you have to handle loss well.”

With all her concentration Faith tries not to wonder how she ranks on this scale. “Do you want to live to a hundred?” she asks her mother.

“Oh yes,” Esther says. “Of course. You can’t imagine it, that’s all. You’re too young. And beautiful. And talented.” No irony. Irony is not her mother’s specialty.

Outside, the men shovelling snow can be heard to say, “Hi, we’re the Weather Channel.” They are speaking to someone watching them out another window from another condo. “In winter the most innocent places can turn lethal,” the same man says and laughs. “Colder’n a well-digger’s dick, you bet,” a second man’s voice says. “That’s today’s forecast.”

“The male appliance,” her mother says pleasantly, fiddling with her cards. “That’s it, isn’t it? The whole mystery.”

“So I’m told,” Faith says.

“They were all women, though.”

“Who was?”

“All the people who lived to be a hundred. You could do all the other things right. But you still needed to be a woman to survive.”

“Lucky us,” Faith says.

“Right. The lucky few.”

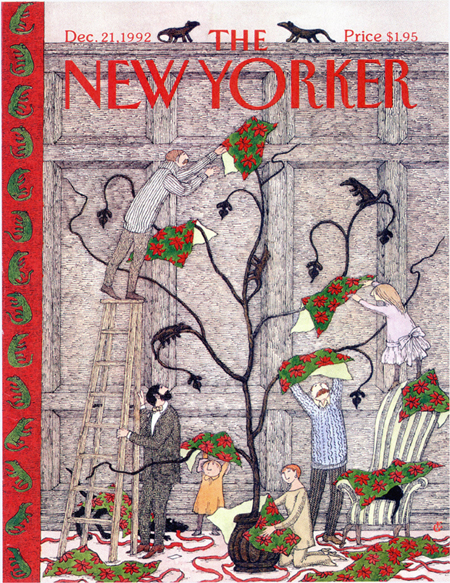

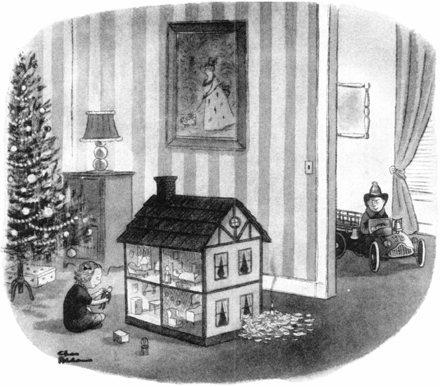

This will be the girls’ first Christmas without a tree or their mother. And Faith has attempted to improvise around this by arranging presents at the base of the large, plastic rubber-tree plant stationed against one of the empty white walls in the living room. She has brought a few red Christmas balls, a gold star, and a string of lights that promise to blink. “Christmas in Manila” could be a possible theme.

Outside, the day is growing dim. Faith’s mother is napping. Roger has gone down to the Warming Shed for a mulled wine following his ski lesson. The girls are seated on the couch side by side, wearing their Lanz of Salzburg flannel nighties with matching smiling-bunny slippers. Green and yellow again, but with printed snowflakes. They have taken their baths together, with Faith present to supervise, then insisted on putting on their nighties early for their nap. To her, these two seem perfect angels and perfectly wasted on their parents.

“We know how to ski now,” Jane says primly. They’re watching Faith trim the rubber-tree plant. First the blinking lights (though there’s no plug-in close enough), then the six red balls (one for each family member). Last will be the gold star. Possibly, Faith thinks, she is trying for too much. Though why not try for too much? It’s Christmas.

“Would you two care to help me?” Faith smiles up at both of them from the floor where she is on her knees fiddling with the fragile green strand of tiny peaked bulbs she already knows will not light up.

“No,” Jane says.

“I don’t blame you,” Faith says.

“Is Mommy coming here?” Marjorie says and blinks, crosses her tiny, pale ankles. She is sleepy and might possibly cry, Faith realizes.

“No, sweet,” Faith says. “This Christmas Mommy is doing herself a big favor. So she can’t do us one.”

“What about Vince?” Jane says authoritatively. Vince is a subject that’s been gone over before. Mrs. Argenbright, the girls’ therapist, has taken special pains with the Vince issue. The girls have the skinny on Mr. Vince but wish to be given it again, since they like him more than their father.

“Vince is a guest of the State of Ohio right now,” Faith says. “You remember that? It’s like he’s in college.”

“He’s not in college,” Jane says.

“Does he have a tree where he is?” Marjorie asks.

“Not in his house, like you do,” Faith says. “Let’s talk about happier things than Mr. Vince, O.K.?”

What furniture the room contains conforms to the Danish style. A raised, metal-hooded, red-enamel-painted fireplace has a paper message from the condo owners taped to it, advising that smoke damage will cause renters to lose their security deposit. The owners are residents of Grosse Pointe Farms, and are people of Russian extraction. Of course, there’s no fireplace wood except for what the furniture could offer.

“I think you two should guess what you’re getting for Christmas,” Faith says, carefully draping lightless lights on the stiff plastic branches. Taking pains.

“In-lines. I already know,” Jane says and crosses her ankles like her sister. They are a jury disguised as an audience. “I don’t have to wear a helmet, though.”

“But are you sure of that?” Faith glances over her shoulder and gives them a smile she has seen movie stars give to strangers. “You could always be wrong.”

“I’d better be right,” Jane says unpleasantly, with a frown very much like one her mom uses.

“Santa’s bringing me a disk player,” Marjorie says. “It’ll come in a small box. I won’t even recognize it.”

“You two’re too smart for your britches,” Faith says. She is quickly finished stringing Christmas lights. “But you don’t know what I brought you.” Among other things, she, too, has brought a disk player and an expensive pair of in-line skates. They are in the Suburban and will be returned in L.A. She has also brought movie videos. Twenty in all, including “Star Wars” and “Sleeping Beauty.” Daisy has sent them each fifty dollars.

“You know,” Faith says, “I remember once a long, long time ago, my dad and I and your mom went out in the woods and cut a tree for Christmas. We didn’t buy a tree, we cut it down with an axe.”

Jane and Marjorie stare at her as if they already know this story. The TV is not turned on in the room. Perhaps, Faith thinks, they don’t understand someone actually talking to them—live action presenting its own unique problems.

“Do you want to hear the story?”

“Yes,” Marjorie, the younger sister, says. Jane sits watchful and silent on the orange Danish sofa. Behind her on the white wall is a framed print of Brueghel’s “Return of the Hunters,” which after all is Christmassy.

“Well,” Faith says. “Your mother and I—we were only nine and ten—we picked out the tree we desperately wanted to be our tree, but our dad said no, that that tree was too tall to fit inside our house. We should choose another one. But we both said, ‘No, this one’s perfect. This is the best one.’ It was green and pretty and had a perfect shape. So our dad cut it down with his axe, and we dragged it through the woods and tied it on top of our car and brought it back to Sandusky.” Both girls have now become sleepy. There has been too much excitement, or else not enough. Their mother is in rehab. Their dad is an asshole. They’re in Michigan. Who wouldn’t be sleepy? “Do you want to know what happened after that?” Faith asks. “When we got the tree inside?”

“Yes,” Marjorie says politely.

“It was too big,” Faith says. “It was much, much too tall. It couldn’t even stand up in our living room. And it was too wide. And our dad got really mad at us because we’d killed a beautiful living tree for a bad reason, and because we hadn’t listened to him and thought we knew everything just because we knew what we wanted.”

Faith suddenly doesn’t know why she’s telling this particular story to these innocent sweeties who do not particularly need an object lesson. So she simply stops. In the real story, of course, her father took the tree and threw it out the door into the back yard, where it stayed for weeks and turned brown. There was crying and accusations. Her father went straight to a bar and got drunk. And later their mother went to the Safeway and bought a small tree that fit and which the three of them trimmed without the aid of their father. It was waiting, trimmed, when he came home smashed. The story had usually been one others found humor in. This time all the humor seemed lacking.

“Do you want to know how the story turned out?” Faith says, smiling brightly for the girls’ benefit, but feeling completely defeated.

“I do,” Marjorie says.

“We put it outside in the yard and put lights on it so our neighbors could share our big tree with us. And we bought a smaller tree for the house at the Safeway. It was a sad story that turned out good.”

“I don’t believe it,” Jane says.

“Well, you should believe it,” Faith says, “because it’s true. Christmases are special. They always turn out wonderfully if you give them a chance and use your imagination.”

Jane shakes her head as Marjorie nods hers. Marjorie wants to believe. Jane, Faith thinks, is a classic older child. Like herself.

“Did you know”—this was one of Greta the girlfriend’s cute messages left for her on her voice mail in Los Angeles—“did you know that Jack hates— hates—to have his dick sucked? Hates it with a passion. Of course you didn’t. How could you? He always lies about it. Oh, well. But if you’re wondering why he never comes, that’s why. It’s a big turnoff for him. I personally think it’s his mother’s fault, not that she ever did it to him, of course. I don’t mean that. By the way, that was a nice dress last Friday. You’re very pretty. And really great tits. I can see why Jack likes you. Take care.”

At seven, the girls wake up from their naps and everyone is hungry at once. Faith’s mother offers to take the two hostile Indians for a pizza, then on to the skating rink, while Roger and Faith share the smorgasbord coupons.

At seven-thirty, few diners have chosen the long, harshly lit, sour-smelling Tyrol Room. Most guests are outside awaiting the nightly Pageant of the Lights, in which members of the ski patrol ski down the expert slope holding lighted torches. It is a thing of beauty but takes time getting started. At the very top of the hill, a great Norway spruce has been lighted in the Yuletide tradition just as in the untrue version of Faith’s story. All is viewable from the Tyrol Room through a big picture window.

Faith does not want to eat with Roger, who is slightly hung over from his gluhwein and a nap. Conversation that she would find offensive could easily occur; something on the subject of her sister, the girls’ mother—Roger’s (still) wife. But she is trying to keep up a Christmas spirit. Do for others, etc.

Roger, she knows, dislikes her, possibly envies her, and is also attracted to her. Once, several years ago, he confided to her that he’d very much like to fuck her ears flat. He was drunk, and Daisy had not long before had Jane. Faith found a way not to acknowledge this offer. Later he told her he thought she was a lesbian. Having her know that just must’ve seemed like a good idea. A class act is the Roger.

The long, wide, echoing dining hall has crisscrossed ceiling beams painted pink and light green and purple—something apparently appropriate to Bavaria. There are long green tables with pink plastic folding chairs meant to promote good times and family fun. Somewhere else in the inn, Faith is certain, there is a better place to eat, where you don’t pay with coupons and nothing’s pink or purple.

Faith is wearing a shiny black Lycra bodysuit, over which she has put on her loden knickers and Norway socks. She looks superb, she thinks. With anyone but Roger this would be fun, or at least a hoot.

Roger sits across the long table, too far away to talk easily. In a room that can conveniently hold five hundred souls, there are perhaps ten scattered diners. No one is eating family style. Only solos and twos. Youthful inn employees in paper caps wait dismally behind the long smorgasbord steam table. Metal heat lamps with orange lights are overcooking the prime rib, of which Roger has taken a goodly portion. Faith has chosen only a few green lettuce leaves, a beet round, and two tiny ears of yellow corn. The sour smell makes eating unappealing.

“Do you know what I worry about?” Roger says, sawing around a triangle of glaucal gray roast-beef fat, using a comically small knife. His tone implies he and Faith lunch together daily and are picking up right where they’ve left off; as if they didn’t hold each other in complete contempt.

“No,” Faith says, “what?” Roger, she notices, has managed to hang on to his red smorgasbord coupon. The rule is you leave your coupon in the basket by the breadsticks. Clever Roger. Why, she wonders, is he tanned?

Roger smiles as though there’s a lewd aspect to whatever it is that worries him. “I worry that Daisy’s going to get so fixed up in rehab that she’ll forget everything that’s happened and want to be married again. To me, I mean. You know?” Roger chews as he talks. He wishes to seem earnest, his smile a serious, imploring, vacuous smile. Roger levelling. Roger owning up.

“Probably that won’t happen,” Faith says. “I just have a feeling.” She no longer wishes to look at her salad. She does not have an eating disorder, she thinks, and could never have one.

“Maybe not.” Roger nods. “I’d like to get out of guidance pretty soon, though. Start something new. Turn the page.”

In truth, Roger is not bad-looking, only oppressively regular: small chin, small nose, small hands, small straight teeth—nothing unusual except his brown eyes, which are slightly too narrow, as if he had Finnish blood. Daisy married him, she said, because of his alarmingly big dick. That or, more important, lack of that, in her view, was why other marriages failed. When all else gave way, that would be there. Vince’s, she’d observed, was even bigger. Ergo. It was to this quest Daisy had dedicated her life. This, instead of college.

“What exactly would you like to do next?” Faith says. She is thinking how satisfying it would be if Daisy came out of rehab and had forgotten everything, and that returning to how things were when they still sort of worked can often be the best solution.

“Well, it probably sounds crazy,” Roger says, chewing, “but there’s a company down in Tennessee that takes apart jetliners. For scrap. And there’s big money in it. I imagine it’s how the movie business got started. Just some harebrained scheme.” Roger pokes macaroni salad with his fork. A single Swedish meatball remains on his plate.

“It doesn’t sound crazy,” Faith lies, then looks longingly at the smorgasbord table. Maybe she is hungry. Is the table full of food the smorgasbord, she wonders, or is eating it the smorgasbord? Roger has slipped his meal coupon back into a pocket. “Do you think you’re going to do that?” she asks with reference to the genius plan of dismantling jet airplanes.

“With the girls in school, it’d be hard,” Roger says, ignoring what would seem to be the obvious—that it is not a genius plan. Faith gazes around distractedly. She realizes no one else in the big room is dressed the way she is, which reminds her of who she is. She is not Snow Mountain Highlands. She is not even Sandusky. She is Hollywood. A fortress.

She has so revolted against the overornate, complicated and expensive Christmas wrapping jobs, says a pal, that she’s seriously considering doing up her parents in old newspapers and string.

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

A thought that has flashed through many a mind.

1961

“I could take the girls for a while,” she suddenly says. “I really wouldn’t mind.” She thinks of sweet Marjorie and sweet but unhappy Jane sitting on the Danish modern couch in their sweet nighties, watching her trim the rubber-tree plant. Just as instantly she thinks of Roger and Daisy being killed in an automobile crash. You can’t help what you think.

“Where would they go to school?” Roger says, alert to something unexpected. Something he likes.

“I’m sorry?” Faith says, and flashes Roger, big-dick Roger, a second movie star’s smile. She has let herself be distracted by the thought of his timely death.

“I mean where would they go to school?” Roger blinks. He is that alert.

“I don’t know. Hollywood High, I guess. They have schools in California. I guess I could find one.”

“I’d have to think about this,” Roger lies decisively.

“O.K.,” Faith says. Now that she has said this without any previous thought of ever saying anything like it, it immediately becomes part of everyday reality. She will soon become the girls’ parent. Easy as that. “When you get settled in Tennessee you could have them back,” she says without conviction.

“They probably wouldn’t want to come back,” Roger says. “Tennessee’d seem pretty dull after Hollywood.”

“Ohio’s dull. They like that.”

“True,” Roger says.

No one, of course, has thought to mention Daisy in preparing this new arrangement. Daisy, the mother. Though Daisy is committed elsewhere for the next little patch. And Roger needs to put “guidance” in the rearview mirror.

The Pageant of the Lights is just now under way—a ribbon of swaying torches swooshing down the expert course like an overflow of lava. All is preternaturally visible through the panoramic window. A large, bundled crowd has assembled at the hill’s bottom, many members holding candles in scraps of paper like at a Grateful Dead concert. All other artificial light is extinguished, except for the big Christmas spruce at the top. The young smorgasbord attendants have gathered at the window to witness the pageant yet again. Some are snickering. Someone remembers to turn the lights off inside the Tyrol Room. Dinner is suspended.

“Do you downhill?” Roger asks, manning his empty plate in the half darkness. Things could really turn out great, Faith understands he’s thinking. Eighty-six the girls. Dismantle plenty jets. Just be friendly.

“No, never,” Faith says, dreamily watching the torchbearers schuss from side to side, a gradual sinuous dramaless tour down. “It scares me.”

“You get used to it.” Roger suddenly reaches across the table where her hands rest on either side of her uneaten salad. He actually touches then pats one of these hands. Roger is her friend now. “And by the way,” he says creepily, “thanks.”

Back in the condo, all is serene. Esther is still at the skating rink. Roger has wandered back to the Warming Shed. He has a girlfriend in Port Clinton. A former high-school counsellee, now divorced. He will be calling her, telling her about the new plans, telling her he wishes she were with him at Snow Mountain Highlands and that his family could be in Rwanda. Bobbie, her name is.

A call to Jack is definitely in order. But first Faith decides to slide the newly trimmed plastic rubber-tree plant nearer the window, where there’s an outlet. When she plugs in, most of the little white lights pop cheerily on. Only a few do not, and in the box are replacements. Later, tomorrow, they can fix the star on top—her father’s favorite ritual. “Now it’s time for the star,” he’d say. “The star of the wise men.” Her father had been a musician, a woodwind specialist. A man of talents, and a drunk. A specialist also in women who were not his wife. He had taught committedly at a junior college to make all their ends meet. He had wanted her to become a lawyer, so naturally she became one. Daisy he had no specific plans for, so she became a drunk, and, sometime later, an energetic nymphomaniac. Eventually he had died, at home. The paterfamilias. After that her mother began to shrink. “I won’t actually die, I intend just to evaporate” was how she put it when the subject arose. It made her laugh. She considered her decrease a natural consequence of loss.

Whether to call Jack in London or New York or Block Island is the question. Where is Jack? In London it was after midnight. In New York and Block Island it was the same as here. Half past eight. Though a message was still the problem. She could just say she was lonely; or had chest pains; or worrisome test results. (The last two of which would later need to clear up mysteriously.)

London, first. The flat in Sloane Terrace, a half block from the tube. They’d eaten breakfast at Oriel, then Jack had gone off to work in the City while she did the Tate, the Bacons her specialty. So far from Snow Mountain Highlands—this is the sensation of dialling—a call going a great distance.

Ring-jing, ring-jing, ring-jing, ring-jing, ring-jing. Nothing.

There was a second number, for messages only, but she’d forgotten it. Call again to allow for a misdial. Ring-jing, ring-jing, ring-jing.…

New York, then. East Forty-ninth. Far, far east. The nice, small slice of river view. A bolt-hole he’d had since college. His freshman numerals framed on the wall. 1971. She’d gone to the trouble to have the bedroom redone. White everything. A smiling picture of her from the boat, framed in red leather. Another of them together at Cabo, on the beach. All similarly long distances from Snow Mountain Highlands.

Ring, ring, ring, ring. Then click, “Hi, this is Jack”—she almost speaks to his voice—“I’m not” etc., etc., etc., then a beep.

“Hi, Jack, it’s me. Ummm, Faith.…” She’s stuck, but not at all flustered. She could just as well tell everything. This happened today: the atomic-energy smokestacks, the rubber-tree plant, the Pageant of the Lights, the smorgasbord, the girls’ planned move to California. All things Christmassy. “Ummm, I just wanted to say that I’m…fine, and that I trust—make that hope—that I hope you are, too. I’ll be back home—in Malibu, that is—after Christmas. I’d love—make that, enjoy—hearing from you. I’m at Snow Mountain Highlands. In Michigan.” She pauses, discussing with herself if there’d be further news to relate. There isn’t. Then she realizes (too late) she’s treating this message machine like her Dictaphone. And there’s no revising. Too bad. Her mistake. “Well, goodbye,” she says, realizing this sounds a bit stiff, but doesn’t revise. There’s Block Island still. Though it’s all over anyway. Who cares? She called.

Out on the Nordic Trail, lights, soft yellow ones not unlike the Christmas-tree lights, have been strung to selected fir boughs—bright enough so you’d never get lost in the dark, dim enough not to spoil the spooky/romantic effect.

She does not really enjoy this kind of skiing either—height or no height—but wants to be a sport. Though there’s the tiresome waxing, the stiff rented shoes, the long, inconvenient skis, the sweaty underneath, the chance that all this could eventuate in catching cold and missing work. The gym is better. Major heat, but then quick you’re clean and back in the car. Back in the office. Back on the phone. She is a sport but not a sports nut. Still, this is not terrifying.

No one is with her on nighttime Nordic Trail 1, the Pageant of the Lights having lured away other skiers. Two Japanese men were at the trailhead. Small beige men in bright chartreuse Lycras—little serious faces, giant thighs, blunt no-nonsense arms—commencing the rigorous course, “the Beast,” Nordic Trail 3. On their small, stocking-capped heads they’d worn lights like coal miners to shine their way. They have disappeared.

Here the snow virtually hums to the sound of her sliding strokes. A full moon rides behind filigree clouds as she strides forward in the near-darkness of crusted woods. There is wind she can hear high up in the tall pines and spruces, but at ground level there’s no wind—just cold radiating off the metallic snow. Only her ears actually feel cold, they and the sweat line of her hair. Her heartbeat is hardly elevated. She is in shape.

For an instant then she hears distant music, a singing voice with orchestral accompaniment. She pauses in her tracks. The music’s pulses travel through the trees. Strange. Possibly, she thinks between deep breaths, it’s Roger—in the karaoke bar, Roger onstage, singing his greatest hits to other lonelies in the dark. “Blue Bayou,” “Layla,” “Tommy,” “Try to Remember.” Roger at a safe distance. Her pale hair, she realizes, is shining in the pure moonlight. If she were being watched, she would look good.

And wouldn’t it be romantic, she thinks, to peer down through the dark woods and spy some great, ornate, and festive lodge lying below, windows ablaze, some exotic casino from a movie. Graceful skaters on a lighted rink. A garlanded lift still in motion, a few, last alpinists taking their silken, torchless float before lights-out. Only there’s nothing to see—dark trunks and deadfalls, swags of snow hung in the spruce boughs.

And she is stiffening. Just this quickly. New muscles visited. No reason to go much farther.

Daisy, her sister, comes to mind. Daisy, who will very soon exit the hospital with a whole new view of life. Inside, there’s of course a twelve-step ritual to accompany the normal curriculum of deprivation and regret. And someone, somewhere, at some time possibly long ago, someone will definitely turn out to have touched Daisy in some way detrimental to her well-being, and at an all too tender age. Once, but perhaps many times, over a series of terrible, silent years. Possibly an older, suspicious neighborhood youth— a loner—or a far too avuncular school librarian. Even the paterfamilias will come under posthumous scrutiny (the historical perspective as always unprovable, yet undisprovable, and therefore indisputable).

And certain sacrifices of dignity will then be requested of everyone, due to this rich new news from the past; a world so much more lethal than anyone believed; nothing the way we thought it was; if they had only known, could’ve spoken out, had opened up the lines of communication, could’ve trusted, confided, blah, blah, blah. Their mother will, necessarily, have suspected nothing, but unquestionably should’ve. Perhaps Daisy herself will have suggested that Faith is a lesbian. The snowball effect. No one safe, no one innocent.

“I’m afraid a wallet would only make him say something sarcastic.”

Up ahead in the shadows, Ski Shelter 1 sits to the right of Nordic Trail 1—a darkened clump in a small clearing, a place to wait for the others to catch up (if there were others). And a perfect place to turn back.

Shelter 1 is open on one side like a lean-to, a murky school-bus enclosure hewn from logs. Out on the snow beside it lie crusts of dinner rolls, a wedge of pizza, some wadded tissue papers, three beer cans—treats for the forest creatures—each casting its tiny shadow upon the white surface.

Though seated in the gloomy inside on a plank bench are not schoolkids but Roger. The brother-in-law, in his powder-blue ski suit and hiking boots. He is not singing karaoke at all. She has noticed no boot tracks up the trail. Roger is more resourceful than first he seems.

“It’s effing cold up here.” Roger speaks from inside the shadows of Shelter 1. He is not wearing his black-frame glasses now, and is hardly visible, although she senses he is smiling—his narrow eyes even narrower.

“What are you doing up here, Roger?”

“Oh,” Roger says from out of the gloom, “I just thought I’d come up.” He crosses his arms, extends his hiking boots into the snow-light like a high-school toughie.

“What for?” Her knees feel knotty and weak from exertion. Her heart has begun thumping. Perspiration is cold on her lip, though. Temperatures are in the low twenties. In winter the most innocent places turn lethal. This is not good.

“Nothing ventured,” Roger says.

“I was just about to turn around,” Faith says.

“I see,” Roger says.

“Would you like to go back down the hill with me?” What she wishes for is more light. Much more light. A bulb in the shelter would be very good. Bad things happen in the dark which would prove unthinkable in the light.

“Life leads you to some pretty interesting places, doesn’t it, Faith?”

She would like to smile. Not feel menaced by Roger, who should be with his daughters.

“I guess,” she says. She can smell alcohol in the dry air. He is drunk, and he is winging all of this. A bad mixture.

“You’re very pretty. Very pretty. The big lawyer,” Roger says. “Why don’t you come in here.”

“Oh, no thank you,” Faith says. Roger is loathsome but he is also family. And she feels paralyzed by not knowing what to do. She wishes she could just leap upward, turn around, glide away.

“I always thought that in the right circumstances, we could have some big-time fun,” Roger goes on.

“Roger, this isn’t a good thing to be doing,” whatever he’s doing. She wants to glare at him, not smile, then realizes her knees are shaking. She feels very, very tall on her skis, unusually accessible.

“It is a good thing to be doing,” Roger says. “It’s what I came up here for. Some fun.”

“I don’t want us to do anything up here, Roger,” Faith says. “Is that all right?” This, she realizes, is what fear feels like—the way you’d feel in a latenight parking structure, or jogging alone in an isolated area, or entering your house in the wee hours, fumbling for a key. Accessible. And then suddenly there would be someone. A man with oppressively ordinary looks who lacks a plan.

“Nope. Nope. That’s not all right,” Roger says. He stands up, but stays in the sheltered darkness. “The lawyer,” Roger says again, still grinning.

“I’m just going to turn around,” Faith says, and very unsteadily begins to shift her long left ski up out of its track, and then, leaning on her poles, her right ski up out of its track. It is unexpectedly dizzying, and her calves ache, and it is complicated not to cross her ski tips. But it is essential to remain standing. To fall would mean surrender. Roger would see it that way. What is the skiing expression? Tele … Tele-something. She wishes she could Tele-something. Tele-something the hell away from here. Her thighs burn. In California, she thinks, she is an officer of the court. A public official, sworn to uphold the law, though regrettably not to enforce it. She is a force for good.

“You look stupid,” Roger says.

She intends to say nothing more. Talk is not cheap now. For a moment she thinks she hears music again, music far away. But it can’t be.

“When you get all the way around,” Roger says, “then I want to show you something.” He does not say what. In her mind—moving her skis inches each time, her ankles stiff and heavy—in her mind she says “Then what?” but doesn’t say that.

“I really hate your whole effing family,” Roger says. His boots go crunch on the snow. She glances over her shoulder, but to look at him is too much. He is approaching. She will fall and then dramatic, regrettable things will happen. In a gesture he himself possibly deems dramatic, Roger—though she cannot see it—unzips his blue ski suit front. He intends her to hear this noise. She is three-quarters turned. She could see him over her left shoulder if she chose to. Have a look at what the excitement is about. She is sweating. Underneath she is drenched.

“Yep. Life leads you to some pretty interesting situations.” There is another zipping noise. It is his best trick. Zip. This is big-time fun in Roger’s world view.

“Yes,” she says, “it does.” She has come fully around now.

She hears Roger laugh, a little chuckle, an unhumorous “hunh.” Then he says, “Almost.” She hears his boots squeeze. She feels his actual self close beside her.

Then there are voices—saving voices—behind her. She now cannot help looking over her left shoulder and up the trail toward where it climbs into the darker trees. There is a light, followed by another light, little stars coming down from a height. Voices, words, language she does not quite understand. Japanese. She does not look at Roger, the girls’ father, but simply slides one ski, her left one, forward into its track, lets her right one follow and find its way, pushes on her poles. And in just that amount of time and with that amount of effort she is away. She thinks she hears Roger say something, another “hunh,” a kind of grunting sound, but can’t be sure.

In the condo everyone is sleeping. The rubber-tree lights are twinkling. They reflect in the window that faces the ski hill, which is now dark. Someone, Faith notices (her mother), has devoted much time to replacing the spent bulbs so the tree can twinkle. The gold star, the star that led the wise men, lies on the coffee table like a starfish, waiting to be properly affixed.

Marjorie, the younger, sweeter sister, is asleep on the orange couch under the Brueghel scene. She has left her bed to sleep near the tree, brought her quilted pink coverlet with her.

Naturally Faith has locked Roger out. Roger can now die alone and cold in the snow. Or he can sleep in a doorway or by a steam vent somewhere in the Snow Mountain Highlands complex and explain his situation to the security staff. Roger will not sleep with his pretty daughters this night. She is taking a hand in things. These girls are hers. Though how strange not to know that her offer to take them would be translated by Roger into an invitation to fuck. She has been in California too long, has fallen out of touch with things middle-American. How strange that Roger would say “effing.” He would also probably say “X-mas.”

Outside on the ice rink two teams are playing hockey under high white lights. A red team opposes a black team. Net cages have been brought on, the larger rink walled off to regulation size and shape. A few spectators stand watching. Wives and girlfriends. Boyne City versus Petoskey; Cadillac versus Cheboygan or some such. The little girls’ white skates lie piled by the door she has now safely locked with a dead bolt.

It would be good to put the star up, she thinks. Who knows what tomorrow will bring. The arrival of wise men couldn’t hurt. So, with the flimsy star, which is made of slick aluminum paper and is large and gold and weightless and five-pointed, Faith stands on the Danish dining-table chair and fits the slotted fastener onto the topmost leaf of the rubber-tree plant. It is not an elegant fit by any means, there being no sprig at the pinnacle, so that the star doesn’t stand as much as it leans off the top in a sad, comic, but also victorious way. (This use was never envisioned by tree-makers in Seoul.) Tomorrow they can all add to the tree together, invent ornaments from absurd and inspirational raw materials. Tomorrow Roger will be rehabilitated and become everyone’s best friend. Except hers.

Marjorie’s eyes have opened, though she has not stirred. For a moment, on the couch, she appears dead.

“I went to sleep,” she says softly and blinks her brown eyes.

“Oh, I saw you,” Faith smiles. “I thought you were just another Christmas present. I thought Santa had been here early and left you for me.” She takes a careful seat on the spindly coffee table, close beside Marjorie—in case there would be some worry to express, a gloomy dream to relate. A fear. She smooths her hand through Marjorie’s warm hair.

Marjorie takes a deep breath and lets air go smoothly through her nostrils. “Jane’s asleep,” she says.

“And how would you like to go back to bed?” Faith says in a whisper.

Possibly she hears a soft tap on the door. The door she will not open. The door beyond which the world and trouble wait. Marjorie’s eyes wander toward the sound, then swim with sleep. She is safe.

“Leave the tree on,” Marjorie instructs, though asleep.

“Sure, sure,” Faith says. “The tree stays on forever.”

She eases her hand under Marjorie, who by old habit reaches outward, caresses her neck. In an instant she has Marjorie in her arms, pink covers and all, carrying her altogether lightly to the darkened bedroom where her sister sleeps on one of the twin beds. Gently she lowers Marjorie onto the empty bed and re-covers her. Again she hears soft tapping, although it stops. She believes it will not come again this night.

Jane is sleeping with her face to the wall, her breathing deep and audible. Jane is the good sleeper, Marjorie the less reliable one. Faith stands in the middle of the dark, windowless room, between the twin beds, the blinking Christmas lights haunting the stillness that has come at such expense. The room smells musty and dank, as if it has been closed for months and opened just for this night, these children. If only briefly she is reminded of Christmases she might’ve once called her own. “O.K.,” she whispers. “O.K., O.K., O.K.”

She undresses in the master suite, too tired to shower. Her mother sleeps on one side of their shared bed. She is an unexpectedly distinguishable presence there, visibly breathing beneath the covers. A glass of red wine half-drunk sits on the bed table beside her curved neck brace. The very same Brueghel print as in the living room hangs over their bed. She will wear pajamas, for her mother’s sake. New ones. White, pure silk, smooth as water. Blue silk piping.

She half closes the bedroom door, the blinking Christmas lights shielded. And here is the unexpected sight of herself in the cheap, dark door mirror. All still good. Intact. Just the small scar where a cyst has been removed between two ribs. A meaningless scar no one would see. Thin, hard thighs. A small nice belly. Boy’s hips. Two good breasts. The whole package, nothing to complain about.

Then the need of a glass of water. Always a glass of water at night, never a glass of red wine. When she passes the living-room window, her destination the kitchen, she sees that the hockey game is now over. It is after midnight. The players are shaking hands in a line on the ice, others skating in wide circles. On the ski slope above the rink, lights have been turned on again. Machines with headlights groom the snow at treacherous angles.

And she sees Roger. He is halfway between the ice rink and the condos, walking back in his powder-blue suit. He has watched the game, no doubt. He stops and looks up at her where she stands in the window in her white p.j.s, the Christmas lights blinking as a background. He stands and stares up. He has found his black-frame glasses. Possibly his mouth is moving, but he makes no gesture to her. There is no room in this inn for Roger.

In bed her mother seems larger. An impressive heat source, slightly damp when Faith touches her back. Her mother is wearing blue gingham, a nightdress not so different from the muumuu she wears in daylight. She smells unexpectedly good. Rich.

How long, she wonders, since she has slept with her mother? A hundred years? Twenty? Odd that it would be so normal now. And good.

She has left the door open in case the girls should call, in case they wake and are afraid, in case they miss their father. She can hear snow slide off the roof, an automobile with chains jingling softly somewhere out of sight. The Christmas lights blink merrily. She had intended to check her messages but let it slip.

Marriage. Yes, naturally she would think of that now. Maybe marriage, though, is only a long plain of self-revelation at the end of which there’s someone else who doesn’t know you very well. That is the message she could’ve left for Jack. “Dear Jack, I now know marriage is a long plain at the end of which there’s” etc., etc., etc. You always think of these things too late. Somewhere, Faith hears faint music, “Away in a Manger,” played prettily on chimes. It is music to sleep to.

And how would they deal with tomorrow? Not the eternal tomorrow, but the promised, practical one. Her thighs feel stiff, though she is slowly relaxing. Her mother, beside her, is facing away. How, indeed? Roger will be rehabilitated, tomorrow, yes, yes. There will be board games. Songs. Changes of outfits. Phone calls placed. Possibly she will find the time to ask her mother if anyone had ever been abused, and find out, happily, not. Looks will be passed between and among everyone tomorrow. Certain names, words will be in short supply for the sake of all. The girls will learn to ski and enjoy it. Jokes will be told. They will feel better. A family again. Christmas, as always, takes care of its own.