E. B. WHITE

At this season of the year, merry to some, not merry to others, we should like to send greetings abroad through town and country. We particularly greet people on benches, and others who wait, motionless, for something to happen. We send Christmas wishes to little auks, and to hunger marchers. To tree surgeons’ mothers, and to men in change booths in the Eighth Avenue subway. To candlemakers and all manufacturers of tops that whir. To people whom clams poison. To people who can’t remember names, and to the persons whose names they can’t remember. To Schrafft’s hostesses. To conditioners of dogs everywhere. We greet all makers of the coffee that beggars want a dime for a cup of. Greetings to the wives of retired army officers. We greet all minor poets, and men who started a mustache Wednesday. To the prisoners in the Yonkers jail, and to little boys whose birthday is December 21. To the fattest woman in the world save three. To receptionists and to the young graduates of universities who fill out cards marked “To see—About—.” To people whose food doesn’t agree with them. To the hatters of Danbury, Conn. To judges of pigeon races, and to manufacturers of gum labels. We greet retouchers of photographs of all sorts, and people who wrestle with bears. Most particularly, though, we send greetings to people on benches, and others who wait, motionless, for something to happen.

1932

They are not wrapped as gifts (there was no time to wrap them), but you will find them under the lighted tree with the other presents. They are the extra gifts, the ones with the hard names. Certain towns and villages. Certain docks and installations. Atolls in a sea. Assorted airstrips, beachheads, supply dumps, rail junctions. Here is a gift to hold in your hand—Hill 660. Vital from a strategic standpoint. “From the Marines,” the card says. Here is a small strip of the Italian coast. Merry Christmas from the members of the American Fifth (who waded ashore). This is Kwajalein, Maloelap, Wotje. This is Eniwetok. Place them with your other atolls, over by the knitted scarf from Aunt Lucy. Here is Gea. If the size isn’t right, remember it was selected at night, in darkness. Roi, Mellu, Boggerlapp, Ennugarret, Ennumennet, Ennubirr. Amphibious forces send season’s greetings. How pretty! A little reef-fringed islet in a coral sea. Kwajalein! A remembrance at Christmas from the Seventh Division. Los Negros Island. Put it with the others of the Admiralty Group. Elements of the First Cavalry Division (dismounted) have sent Momote airfield, a very useful present. Manus, largest of the Admiralties. Lorengau, taken from the Japanese garrison in the underground bunkers. Talasea airdrome. Wotho Atoll (a gift from the 22nd Marine Regiment). Emirau Island, and ten more atolls in the Marshalls to make your Christmas bright in 1944: Ujae, Lae, Lib, Namu, Ailinglapalap (never mind the names), together with a hundred-and-fifty-mile strip of the northern New Guinea coast, Tanahmera Bay and Humboldt Bay, together with Hollandia. “From some American troops covered with red mud.”

Here is a novel gift—a monastery on a hill. It seems to have been damaged. A bridge on Highway 6. A mountain stronghold, Castelforte (Little Cassino, they used to call it). And over here the roads—Via Casilina and the Appian Way. Valleys, plains, hills, roads, and the towns and villages. Santa Maria Infante, San Pietro, Monte Cerri, and Monte Bracchi. One reads the names on the cards with affection. Best wishes from the Fifth. Gaeta, Cisterna, Terracina, the heights behind Velletri, the Alban Hills, Mount Peschio, and the fortress of Lazio. Velletri and Valmontone. Best wishes from the Fifth. The suburbs of Rome, and Rome. The Eternal City! Holiday greetings from the American Fifth.

Who wouldn’t love the Norman coast for Christmas? Who hasn’t hoped for the Atlantic Wall, the impregnable? Here is the whole thing under the lighted tree. First the beaches (greetings from the Navy and the Coast Guard), then the cliffs, the fields behind the cliffs, the inland villages and towns, the key places, the hedgerows, the lanes, the houses, and the barns. Ste. Mère Eglise (with greetings from Omar Bradley and foot soldiers). This Norman cliff (best from the Rangers). St. Jacques de Nehou (from the 82nd Airborne Division, with its best). Cherbourg—street by street, and house by house. St. Remy des Landes, La Broquière, Baudreville, Neufmesnil, La Poterie, the railroad station at La Haye du Puits. And then St. Lô, and the whole vista of France. When have we received such presents? Saipan in the Marianas—only they forgot to take the price tag off. Saipan cost 9,752 in dead, wounded, and missing, but that includes a mountain called Tapotchau. Guam. “Merry Christmas from Conolly, Geiger, and the boys.” Tinian, across the way. Avranches, Gavray, Torigny-sur-Vire, a German army in full retreat under your tree. A bridge at Pontorson, a bridge at Ducey, with regards from those who take bridges. Rennes, capital of Brittany (our columns fan out). Merry Christmas, all! Brest, Nantes, St. Malo, a strategic fortress defended for two weeks by a madman. Toulon, Nice, St. Tropez, Cannes (it is very gay, the Riviera, very fashionable). And now (but you must close your eyes for this one) … Paris.

Still the gifts come. You haven’t even noticed the gift of the rivers Marne and Aisne. Château-Thierry, Soissons (this is where you came in). Verdun, Sedan (greetings from the American First Army, greetings from the sons of the fathers). Here is a most unusual gift, a bit of German soil. Priceless. A German village, Roetgen. A forest south of Aachen. Liége, the Belfort Gap, Geilenkirchen, Crucifix Hill, Uebach. Morotai Island in the Halmaheras. An airport on Peleliu. Angaur (from the Wildcats). Nijmegen Bridge, across the Rhine. Cecina, Monteverdi, more towns, more villages on the Tyrrhenian coast. Leghorn. And, as a special remembrance, sixty-two ships of the Japanese Navy, all yours. Tacloban, Dulag, San Pablo … Ormoc. Valleys and villages in the Burmese jungle. Gifts in incredible profusion and all unwrapped, from old and new friends: gifts with a made-in-China label, gifts from Russians, Poles, British, French, gifts from Eisenhower, de Gaulle, Montgomery, Malinovsky, an umbrella from the Air Forces, gifts from engineers, rear gunners, privates first class … there isn’t time to look at them all. It will take years. This is a Christmas you will never forget, people have been so generous.

1944

To perceive Christmas through its wrapping becomes more difficult with every year. There was a little device we noticed in one of the sporting-goods stores—a trumpet that hunters hold to their ears so that they can hear the distant music of the hounds. Something of the sort is needed now to hear the incredibly distant sound of Christmas in these times, through the dark, material woods that surround it. “Silent Night,” canned and distributed in thundering repetition in the department stores, has become one of the greatest of all noisemakers, almost like the rattles and whistles of Election Night. We rode down on an escalator the other morning through the silentnighting of the loudspeakers, and the man just in front of us was singing, “I’m gonna wash this store right outa my hair, I’m gonna wash this store …”

The miracle of Christmas is that, like the distant and very musical voice of the hound, it penetrates finally and becomes heard in the heart—over so many years, through so many cheap curtain-raisers. It is not destroyed even by all the arts and craftiness of the destroyers, having an essential simplicity that is everlasting and triumphant, at the end of confusion. We once went out at night with coon-hunters and we were aware that it was not so much the promise of the kill that took the men away from their warm homes and sent them through the cold shadowy woods, it was something more human, more mystical—something even simpler. It was the night, and the excitement of the note of the hound, first heard, then not heard. It was the natural world, seen at its best and most haunting, unlit except by stars, impenetrable except to the knowing and the sympathetic.

Christmas in 1949 must compete as never before with the dazzling complexity of man, whose tangential desires and ingenuities have created a world that gives any simple thing the look of obsolescence—as though there were something inherently foolish in what is simple, or natural. The human brain is about to turn certain functions over to an efficient substitute, and we hear of a robot that is now capable of handling the tedious details of psychoanalysis, so that the patient no longer need confide in a living doctor but can take his problems to a machine, which sifts everything and whose “brain” has selective power and the power of imagination. One thing leads to another. The machine that is imaginative will, we don’t doubt, be heir to the ills of the imagination; one can already predict that the machine itself may become sick emotionally, from strain and tension, and be compelled at last to consult a medical man, whether of flesh or of steel. We have tended to assume that the machine and the human brain are in conflict. Now the fear is that they are indistinguishable. Man not only is notably busy himself but insists that the other animals follow his example. A new bee has been bred artificially, busier than the old bee.

So this day and this century proceed toward the absolutes of convenience, of complexity, and of speed, only occasionally holding up the little trumpet (as at Christmastime) to be reminded of the simplicities, and to hear the distant music of the hound. Man’s inventions, directed always onward and upward, have an odd way of leading back to man himself, as a rabbit track in snow leads eventually to the rabbit. It is one of his more endearing qualities that man should think his tracks lead outward, toward something else, instead of back around the hill to where he has already been; and it is one of his persistent ambitions to leave earth entirely and travel by rocket into space, beyond the pull of gravity, and perhaps try another planet, as a pleasant change. He knows that the atomic age is capable of delivering a new package of energy; what he doesn’t know is whether it will prove to be a blessing. This week, many will be reminded that no explosion of atoms generates so hopeful a light as the reflection of a star, seen appreciatively in a pasture pond. It is there we perceive Christmas—and the sheep quiet, and the world waiting.

“Oh dear! And we didn’t send them a card!”

THE SPIRIT

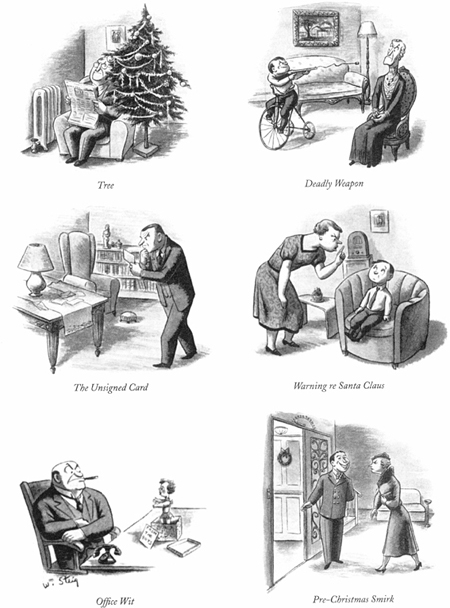

A man we’ve heard of, an aging codger who is obviously bucking for the post of permanent honorary Santa Claus in his community (which shall be nameless here), sends one or two unsigned Christmas cards to a number of younger people there—the kind who are inclined to worry about whether they will receive Christmas greetings from their professional or social idols. “They sent this card and forgot to sign it,” he pictures them telling themselves happily.

—CARROLL NEWMAN

AND ST. CLAIR McKELWAY. 1961

From this high midtown hall, undecked with boughs, unfortified with mistletoe, we send forth our tinselled greetings as of old, to friends, to readers, to strangers of many conditions in many places. Merry Christmas to uncertified accountants, to tellers who have made a mistake in addition, to girls who have made a mistake in judgment, to grounded airline passengers, and to all those who can’t eat clams! We greet with particular warmth people who wake and smell smoke. To captains of river boats on snowy mornings we send an answering toot at this holiday time. Merry Christmas to intellectuals and other despised minorities! Merry Christmas to the musicians of Muzak and men whose shoes don’t fit! Greetings of the season to unemployed actors and the blacklisted everywhere who suffer for sins uncommitted; a holly thorn in the thumb of compilers of lists! Greetings to wives who can’t find their glasses and to poets who can’t find their rhymes! Merry Christmas to the unloved, the misunderstood, the overweight. Joy to the authors of books whose titles begin with the word “How” (as though they knew)! Greetings to people with a ringing in their ears; greetings to growers of gourds, to shearers of sheep, and to makers of change in the lonely underground booths! Merry Christmas to old men asleep in libraries! Merry Christmas to people who can’t stay in the same room with a cat! We greet, too, the boarders in boarding houses on 25 December, the duennas in Central Park in fair weather and foul, and young lovers who got nothing in the mail. Merry Christmas to people who plant trees in city streets; Merry Christmas to people who save prairie chickens from extinction! Greetings of a purely mechanical sort to machines that think—plus a sprig of artificial holly. Joyous Yule to Cadillac owners whose conduct is unworthy of their car! Merry Christmas to the defeated, the forgotten, the inept; joy to all dandiprats and bunglers! We send, most particularly and most hopefully, our greetings and our prayers to soldiers and guardsmen on land and sea and in the air—the young men doing the hardest things at the hardest time of life. To all such, Merry Christmas, blessings, and good luck! We greet the Secretaries-designate, the President-elect: Merry Christmas to our new leaders, peace on earth, good will, and good management! Merry Christmas to couples unhappy in doorways! Merry Christmas to all who think they’re in love but aren’t sure! Greetings to people waiting for trains that will take them in the wrong direction, to people doing up a bundle and the string is too short, to children with sleds and no snow! We greet ministers who can’t think of a moral, gagmen who can’t think of a joke. Greetings, too, to the inhabitants of other planets; see you soon! And last, we greet all skaters on small natural ponds at the edge of woods toward the end of afternoon. Merry Christmas, skaters! Ring, steel! Grow red, sky! Die down, wind! Merry Christmas to all and to all a good morrow!

1952

As Christmas draws near, there seems to be less peace on the earth of the Holy Land than practically anywhere else, and we therefore wish an extra portion of good will to all who live beneath the Star of Bethlehem. We wish a surcease of rancor to the angry, a sackful of restraint to the hotheaded, and to everybody a moratorium on political debts. Our merriest Christmas wishes go to those whose lives have been harried by holiday preliminaries: to the novice skaters at Rockefeller Center, forced to take their lessons before so unusually many challenging eyes; to Salvation Army tuba players on Fifth Avenue, manfully making their music despite the double jeopardy of cold lip and jostled elbow; to a temporary saleswoman we saw at Saks with tears in her eyes and the book “Creatures of Circumstance” tucked under her arm; to a bulky, mink-clad lady we bumped into on Madison Avenue, who (a prep-school mother?) was trying to look as if she habitually walked around carrying a brace of hockey sticks; to the girl in the Barton’s candy ad, nibbling self-consciously on a chocolate Christmas card; and to a young man we watched directing pedestrian traffic in front of the Lord & Taylor show windows (he was wearing a crash helmet, and we hope he survived). Our especially sympathetic regards go to those anonymous bulwarks of industry, the people who clean up offices after office parties. May they all find a bottle of Christmas cheer cached behind a filing cabinet!

We wish a Merry Christmas to the man in the moon, and also to an enterprising Long Island man who has been selling earth dwellers lots on the moon. (A Happy Light-Year to his customers.) Merry Christmas and congratulations to the ninety-two-year-old doctor to whom the Army—which now has forty-one generals of a rank equal to or higher than the loftiest attained by George Washington—has just given a reserve promotion from captain to major. Merry Christmas to Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, who has turned sixty-five, and may he, too, make the grade ere long. Merry Christmas, when it comes to that, to the Army, which has indulgently permitted a pfc. in Korea to retain ownership of some land he impulsively bought there, for the establishment of an orphanage.

THAT’S TOO BAD DEPARTMENT

[Headline in the Saratogian]

CHRISTMAS CALLED NOEL IN PARIS, SARATOGIAN WHO RESIDED THERE SAYS.

1938

Merry Christmas to all orphans and strays everywhere, including our dog, who vanished last week. May somebody throw her a bone. Merry Christmas to all the defenders of lost and little causes, among them an animal-loving outfit beguilingly called Defenders of Furbearers. (Merry Christmas to furriers, too.) Merry Christmas to all the institutions endowed by the Ford Foundation, and a particularly rollicking Noël to one beneficiary—the hard-pressed hospital that reluctantly closed its doors on December 1st, never dreaming that succor was imminent. (What delightful evidence that Santa comes only when your eyes are shut!) Merry Christmas to the Foundation’s controversial offspring, the Fund for the Republic, which is under considerable political attack at the moment and has just diplomatically added two offspring of literary men to a panel of judges for a TV-program contest it is sponsoring—Robert A. Taft, Jr., whose father wrote “A Foreign Policy for Americans,” and Philip Willkie, whose father wrote “One World.” Merry Christmas to one world, including all Germanys, all Koreas, all Vietnams, all Chinas, and both Inner and Outer Mongolia.

HOLIDAY TRIALS