CHAPTER SEVEN

THE TRIUMPH OF HOPE

The French Revolution was a Utopian attempt to overthrow a traditional order—one with many imperfections, certainly—in the name of abstract ideas, formulated by vain intellectuals, which lapsed, not by chance but through weakness and wickedness, into purges, mass murder and war. In so many ways it anticipated the still more terrible Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

[P]erhaps the ultimately decisive factor . . . is that characteristic of revolutionary situations described by Alexis de Tocqueville more than a century ago: the ruling elite’s loss of belief in its own right to rule. A few kids went on the streets and threw a few words. The police beat them. The kids said: You have no right to beat us! And the rulers, the high and mighty, replied, in effect: Yes, we have no right to beat you. We have no right to preserve our rule by force. The end no longer justifies the means.

THE YEAR 1989 marked the 200th anniversary of the great revolution in France that swept away the ancien régime, and with it the old idea that governments could base their authority on a claim of inherited legitimacy. Even as the celebrations were taking place, another revolution in Eastern Europe was sweeping away a somewhat newer idea: that governments could base their legitimacy on an ideology that claimed to know the direction of history. There was a certain delayed justice in this, for what happened in 1989 was what was supposed to have happened in Russia in 1917: a spontaneous uprising of workers and intellectuals of the kind Marx and Lenin had promised would produce a classless society throughout the world. But the Bolshevik Revolution had hardly been spontaneous, and over the next seven decades the ideology it empowered produced only dictatorships which called themselves people’s democracies. It seemed appropriate, then, that the revolutions of 1989 rejected Marxism-Leninism even more decisively than the French Revolution two centuries earlier had overthrown the divine right of kings.

Nevertheless, the upheavals of 1989, like those of 1789, caught everyone by surprise. Historians could of course look back, after the fact, and specify causes: frustration that the temporary divisions of the World War II settlement had become the permanent divisions of the postwar era; fear of the nuclear weapons that had produced that stalemate; resentment over the failure of command economies to raise living standards; a slow shift in power from the supposedly powerful to the seemingly powerless; the unexpected emergence of independent standards for making moral judgments. Sensing these trends, the great actor-leaders of the 1980s had found ways to dramatize them to make the point that the Cold War need not last forever. Not even they, however, foresaw how soon and how decisively it would end.

What no one understood, at the beginning of 1989, was that the Soviet Union, its empire, its ideology—and therefore the Cold War itself—was a sandpile ready to slide. All it took to make that happen were a few more grains of sand.

3 The people who dropped them were not in charge of superpowers or movements or religions: they were ordinary people with simple priorities who saw, seized, and sometimes stumbled into opportunities. In doing so, they caused a collapse no one could stop. Their “leaders” had little choice but to follow.

One particular leader, however, did so in a distinctive way. He ensured that the great 1989 revolution was the first one ever in which almost no blood was shed. There were no guillotines, no heads on pikes, no officially sanctioned mass murders. People did die, but in remarkably small numbers for the size and significance of what was happening. In both its ends and its means, then, this revolution became a triumph of hope. It did so chiefly because Mikhail Gorbachev chose not to act, but rather to be acted upon.

I.

THE YEAR began quietly enough with the inauguration, on January 20, 1989, of George H. W. Bush as president of the United States. As Reagan’s vice president, Bush had witnessed Gorbachev’s emergence and the events that followed, but he was less convinced than his predecessor of their revolutionary character: “Did we see what was coming when we took office? No, we did not, nor could we have planned it.”

4 The new chief executive wanted a pause for reassessment, and so ordered a review of Soviet-American relations that took months to complete. Brent Scowcroft, Bush’s national security adviser, was even more doubtful:

I was suspicious of Gorbachev’s motives and skeptical about his prospects. . . . He was attempting to kill us with kindness. . . . My fear was that Gorbachev could talk us into disarming without the Soviet Union having to do anything fundamental to its own military structure and that, in a decade or so, we could face a more serious threat than ever before.

5

Gorbachev, for his part, was wary of the Bush administration. “These people were brought up in the years of the Cold War and still do not have any foreign policy alternative,” he told the Politburo shortly before Bush took office. “I think that they are still concerned that they might be on the losing side. Big breakthroughs can hardly be expected.”

6That Bush and Gorbachev anticipated so little suggests how little control they had over what was about to happen. Calculated challenges to the status quo, of the kind John Paul II, Deng, Thatcher, Reagan, and Gorbachev himself had mounted over the past decade, had so softened the status quo that it now lay vulnerable to less predictable assaults from little-known leaders, even from unknown individuals. Scientists know this condition as “criticality”: a minute perturbation in one part of a system can shift—or even crash—the entire system.

7 They also know the impossibility of anticipating when, where, and how such disruptions will occur, or what their effects will be. Gorbachev was no scientist, but he came to see this. “[L]ife was developing with its own dynamism,” he commented in November. “[E]vents were moving very fast . . . and one should not fall behind. . . . There was no other way for a leading party to act.”

8This pattern of leading parties scrambling not to fall behind showed up first in Hungary, where since Khrushchev’s suppression of the 1956 uprising János Kádár’s regime had slowly, steadily, and discreetly regained a degree of autonomy within the Soviet bloc. By the time Gorbachev came to power in 1985, Hungary had the most advanced economy in Eastern Europe, and was beginning to experiment with political liberalization. Younger reformers forced Kádár to retire in 1988, and early in 1989 the new Hungarian prime minister, Miklós Németh, visited Gorbachev in Moscow. “Every socialist country is developing in its idiosyncratic way,” Németh reminded his host, “and their leaders are above all accountable to their own people.” Gorbachev did not disagree. The 1956 protests, he admitted, had begun “with the dissatisfaction of the people.” They had only then “escalated into a counterrevolution and bloodshed. This cannot be overlooked.”

9The Hungarians certainly did not overlook what Gorbachev had said. They had already established an official commission to reassess the events of 1956. The rebellion, it concluded, had been a “popular uprising against an oligarchic system of power which had humiliated the nation.” When it became clear that Gorbachev would not object to this finding, the authorities in Budapest approved a ceremonial acknowledgment of it: the reburial of Imre Nagy, the Hungarian premier who had led the rebellion, and whom Khrushchev had ordered executed. Two hundred thousand Hungarians attended the state funeral, an emotional event held on June 16, 1989. Meanwhile Németh, on his own authority, had taken a more significant step. He refused to approve funds for the continued maintenance of the barbed wire along the border between Hungary and Austria, across which the refugees of 1956 had tried to flee. Then, on the grounds that the barrier was obsolete and hence a health hazard, he ordered the guards to begin dismantling it. The East Germans, alarmed, protested to Moscow, but the surprising word came back: “We can’t do anything about it.”

10Equally unexpected developments were taking place in Poland, where Jaruzelski had long since released Wałęsa from prison and lifted martial law. During the late 1980s the government had performed a delicate dance with Solidarity—still officially banned—as each sought legitimacy while discovering a mutual dependency. By the spring of 1989 the economy was in crisis yet again. Jaruzelski tried to solve the problem by re-recognizing Solidarity and allowing its representatives to compete in a “non-confrontational” election for a new bicameral legislature. Wałęsa went along reluctantly, expecting the elections to be rigged. But to everyone’s astonishment, Solidarity’s candidates swept all the seats they had contested in the lower house, and all but one in the upper house.

The June 4th results had been “a huge, startling success,” one Solidarity organizer commented, and Wałęsa found himself scrambling once more, this time to help

Jaruzelski save face. “Too much grain has ripened for me,” he joked, “and I can’t store it all in my granary.” Moscow’s reaction was not what it had been to Solidarity’s rise a decade earlier. “This is entirely a matter to be decided by Poland,” one of Gorbachev’s top aides commented. And so on August 24, 1989, the first non-communist government in postwar Eastern Europe formally took power. The new prime minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, was sufficiently shaken by what had happened that he fainted during his own installation ceremony.

11Gorbachev by this time had already allowed elections in the Soviet Union for a new Congress of People’s Deputies: he had “not give[n] a thought,” he told Jaruzelski, “to hampering changes.”

12 The Congress convened in Moscow on May 25th, and for several days television viewers throughout the U.S.S.R. relished the unprecedented sight of a vociferous opposition haranguing the government. “[E]veryone was so sick of singing the praises of Brezhnev that it now became a must to chide the leader,” Gorbachev recalled. “Being disciplined people, my Politburo colleagues did not show that they were unhappy. Nevertheless, I sensed their bad mood. How could it be otherwise when it was already clear to everybody that the days of Party dictatorship were over?”

13However true that might be in Hungary, Poland, and the Soviet Union, it was not the case in China. There Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms had brought pressures for political change, a course he was not prepared to take. When former general secretary Hu Yaobang, whom Deng had deposed for having advocated openness, suddenly died in mid-April, student protesters began a series of demonstrations that filled Tiananmen Square, in central Beijing. Gorbachev, on his first trip to China, arrived in the midst of these. “Our hosts,” he observed, “were extremely concerned about the situation,” and with good reason, for the dissidents cheered the Kremlin leader. “In the Soviet Union they have Gorbachev,” one banner read. “In China, we have whom?” Shortly after his departure, the students unveiled a plaster “Goddess of Democracy,” modeled on the Statue of Liberty, directly across from Mao’s portrait over the entrance to the Forbidden City and just in front of his mausoleum.

14Whatever Mao might have thought of this, it was too much for Deng, and on the night of June 3–4, 1989, he ordered a brutal crackdown. How many people died as the army took back the square and the streets surrounding it is still not clear, but the toll was several times greater than that for the entire year of revolutionary upheavals in Europe.

15 Nor is there a consensus, even now, as to how the Chinese Communist Party retained power when its European counterparts were losing power: perhaps it was the willingness to use force; perhaps the fear of chaos if the party was overthrown; perhaps the fact that Deng’s version of capitalism in the guise of communism had genuinely improved the lives of the Chinese people, however stunted their opportunities for political expression might be. What was clear was that Gorbachev’s example had shaken Deng’s authority. Whether Deng’s example would now shake Gorbachev’s authority remained to be seen.

One European communist who hoped it might was Erich Honecker, the long-time hard-line ruler of East Germany. His most recent election, held in May, 1989, had produced an implausible 98.95 percent vote in favor of his government. After the Tiananmen massacre Honecker’s secret police chief, Erich Mielke, commended the Chinese action to his subordinates as “resolute measures in suppression of. . . counterrevolutionary unrest.” East German television repeatedly ran a Beijing-produced documentary praising “the heroic response of the Chinese army and police to the perfidious inhumanity of the student demonstrators.”

16 All of this seemed to suggest that Honecker had the German Democratic Republic under control—until the regime noticed that an unusually large number of its citizens were taking their summer vacations in Hungary.

When the Hungarian authorities took down the barbed wire along the Austrian border, they had intended only to make it easier for their own citizens to get through. But the word spread, and soon thousands of East Germans were driving their tiny wheezing polluting Trabants through Czechoslovakia and Hungary to the border, abandoning them there, and walking across. Others crowded into the West German embassy in Budapest, demanding asylum. By September, there were 130,000 East Germans in Hungary and the government announced that, for “humanitarian” reasons, it would not try to stop their emigration to the West. Honecker and his associates were furious: “Hungary is betraying socialism,” Mielke fumed. “We have to guard against being discouraged,” another party official warned. “[B]ecause of developments in the Soviet Union, Poland, and Hungary . . . [m]ore and more people are asking how is socialism going to survive at all?”

17That was an excellent question, for soon some 3,000 East German asylum-seekers had climbed the fence surrounding West Germany’s embassy in Prague and crammed themselves inside, with full television coverage. The Czech government, unhappy about the publicity but unwilling to open its own borders, pressed Honecker to resolve the situation. With the G.D.R.’s fortieth anniversary coming up the following month, he too was eager to end the embarrassment. He finally agreed that the East Germans in Prague could go to West Germany, but only in sealed trains traveling through the territory of the G.D.R., which would allow him to claim that he had expelled them. The trains were cheered along the way, though, and additional East Germans tried to board them. When the police asked to see identity cards one last time, some passengers threw them at their feet. “The feeling was,” one remembered, “‘There’s your card—you can’t threaten me anymore.’ It was very satisfying.”

18Meanwhile guests—including Gorbachev himself—were arriving in East Berlin for the official commemorations on October 7–8, 1989. To the horror of his hosts, the Soviet leader turned out to be even more popular than he had been in Beijing. During the parade down the Unter den Linden the marchers abandoned the approved slogans and began shouting, “Gorby, help us! Gorby, stay here!” Watching from the reviewing platform next to an ashen Honecker, Gorbachev could see that

[t]hese were specially chosen young people, strong and goodlooking. . . . [Jaruzelski], the Polish leader, came up to us and said, “Do you understand German?” I said, “I do, a little bit.” “Can you hear?” I said, “I can.” He said, “This is the end.” And that was the end: The regime was doomed.

Gorbachev tried to warn the East Germans of the need for drastic changes: “[O]ne cannot be late, otherwise one will be punished by life.” But as he later recalled, “Comrade Erich Honecker obviously considered himself No. 1 in socialism, if not in the world. He did not really perceive any more what was actually going on.” Trying to get through to him was “like throwing peas against a wall.”

19Anti-government protests had been building for weeks in Leipzig, and they resumed on October 9th, the day after Gorbachev returned to Moscow. With the Soviet guest gone, the possibility of a Deng Xiaoping solution was still there: Honecker may even have authorized one. But at this point an unexpected actor—Kurt Masur, the widely respected conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra—intervened to negotiate an end to the confrontation, and the security forces withdrew. There was no Tiananmen-like massacre, but that meant that there was no authority left for Honecker, who was forced to resign on October 18th. His successor, Egon Krenz, had attended the fortieth anniversary celebration of Mao’s revolution in Beijing a few weeks earlier, but he did not think that firing on demonstrators would work in East Germany. It would not happen, he assured Gorbachev on November 1st, even if the unrest spread to East Berlin. There might be an attempt “to break through the Wall,” Krenz added, “[b]ut such a development was not very likely.”

20What Krenz did not expect was that one of his own subordinates, by botching a press conference, would breach the wall. After returning from Moscow Krenz consulted his colleagues, and on November 9th they decided to try to relieve the mounting tension in East Germany by relaxing—not eliminating—the rules restricting travel to the West. The hastily drafted decree was handed to Günter Schabowski, a Politburo member who had not been at the meeting but was about to brief the press. Schabowski glanced at it, also hastily, and then announced that citizens of the G.D.R. were free to leave “through any of the border crossings.” The surprised reporters asked when the new rules went into effect. Shuffling through his papers, Schabowski replied: “[A]ccording to my information, immediately.” Were the rules valid for travel to West Berlin? Schabowski frowned, shrugged his shoulders, shuffled some more papers, and then replied: “Permanent exit can take place via all border crossings from the G.D.R. to [West Germany] and West Berlin, respectively.” The next question was: “What is going to happen to the Berlin Wall now?” Schabowski mumbled an incoherent response, and closed the press conference.

21Within minutes, the word went out that the wall was open. It was not, but crowds began gathering at the crossing points and the guards had no instructions. Krenz, stuck in a Central Committee meeting, had no idea what was happening, and by the time he found out the crush of people was too large to control. At last the border guards at Bornholmer Strasse took it upon themselves to open the gates, and the ecstatic East Berliners flooded into West Berlin. Soon Germans from both sides were sitting, standing, and even dancing on top of the wall; many brought hammers and chisels to begin knocking it down. Gorbachev, in Moscow, slept through the whole thing and heard about it only the next morning. All he could do was pass the word to the East German authorities: “[Y]ou made the right decision.”

22With the wall breached, everything was possible. On November 10th, Todor Zhivkov, Bulgaria’s ruler since 1954, announced that he was stepping down; soon the Bulgarian Communist Party was negotiating with the opposition and promising free elections. On November 17th, demonstrations broke out in Prague and quickly spread throughout Czechoslovakia. Within weeks, a coalition government had ousted the communists, and by the end of the year Alexander Dubček, who had presided over the 1968 “Prague spring,” was installed as chairman of the national assembly, reporting to the new president of Czechoslovakia—Václav Havel.

And on December 17th the Romanian dictator Nicolai Ceauşescu, desperate to preserve his own regime, ordered his army to follow the Chinese example and shoot down demonstrators in Timişoara. Ninetyseven were killed, but that only fueled the unrest, leading Ceauşescu to call a mass rally of what he thought would be loyal supporters in Bucharest on December 21st. They turned out not to be, began jeering him, and before it could be cut off the official television transmission caught his deer-in-the-headlights astonishment as he failed to calm the crowd. Ceauşescu and his wife, Elena, fled the city by helicopter but were quickly captured, put on trial, and executed by firing squad on Christmas Day.

23Twenty-one days earlier, Ceauşescu had met with Gorbachev in the Kremlin. Recent events in Eastern Europe, he warned, had placed “in grave danger not just socialism in the respective countries but also the very existence of the communist parties there.” “You seem concerned about this,” Gorbachev responded, sounding more like a therapist than a Kremlin boss. “[T]ell me, what can we do?” Ceauşescu suggested vaguely: “[W]e could have a meeting and discuss possible solutions.” That would not be enough, Gorbachev replied: change was necessary; otherwise one might wind up having to solve problems “under the marching of boots.” But the East European prime ministers would be meeting on January 9th. And then Gorbachev unwisely assured his anxious guest: “You shall be alive on the 9[th of] January.”

24It had been a good year for anniversaries, but a bad year for predictions. At the beginning of 1989, the Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe seemed as solid as it had been for the past four and a half decades. But in May, Gorbachev’s aide Chernyaev was noting gloomily in his diary: “[S]ocialism in Eastern Europe is disappearing. . . . Everywhere things are turning out different from what had been imagined and proposed.” By October, Gennadi Gerasimov, the Soviet foreign ministry press spokesman, could even joke about it. “You know the Frank Sinatra song ‘My Way’?” he replied, when asked what was left of the Brezhnev Doctrine. “Hungary and Poland are doing it their way. We now have the Sinatra doctrine.”

25 At the end of the year, nothing was left: what the Red Army had won in World War II, what Stalin had consolidated, what Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Andropov, and even Chernenko had sought to preserve, was all lost. Gorbachev was determined to make the best of it.

“By no means should everything that has happened be considered in a negative light,” he told Bush at their first summit meeting, held at Malta in December, 1989:

We have managed to avoid a large-scale war for 45 years. . . . [C]onfrontation arising from ideological convictions has not justified itself either. . . . [R]eliance on unequal exchange between developed and underdeveloped countries has also been a failure. . . . Cold War methods . . . have suffered defeat in strategic terms. We have recognized this. And ordinary people have possibly understood this even better.

The Soviet leadership, the Soviet leader informed the American president, “have been reflecting about this for a long time and have come to the conclusion that the US and the USSR are simply ‘doomed’ to dialogue, coordination, and cooperation. There is no other choice.”

26

II.

BUSH ADMITTED to Gorbachev at the Malta summit that the United States had been “shaken by the rapidity of the unfolding changes” in Eastern Europe. He had changed his own position “by 180 degrees.” He was trying “to do nothing which would lead to undermining your position.” Perhaps with Reagan in mind, he promised that he would not “climb the Berlin Wall and make high-sounding pronouncements.” But Bush went on to say: “I hope you understand that it is impossible to demand of us that we disapprove of German reunification.” Gorbachev responded only by noting that “[b]oth the USSR and the US are integrated into European problems to different degrees. We understand your involvement in Europe very well. To look otherwise at the role of the US in the Old World is unrealistic, mistaken, and finally not constructive.”

27A lot was implied in these exchanges. Bush was confirming that his administration had been caught off guard—as had everyone else—by what had happened. He was acknowledging Gorbachev’s importance in these events: the United States did not wish to weaken him. But Bush was also signaling that the Americans and the West Germans intended now to push for German reunification, something that would have seemed wildly impractical only a few weeks earlier. Gorbachev’s response was equally significant, both for what he did and did not say. He welcomed the United States as a European power, something no Soviet leader had explicitly done before. And his silence on Germany suggested ambivalence: that too was an unprecedented position for a regime that had sought reunification after World War II only if all of Germany could be Marxist, and when that proved impossible had committed itself to keeping Germany permanently divided.

There had been hints that Gorbachev might modify this position. He had told West German President Richard von Weizsäcker in 1987 that although the two German states were a current reality, “[w]here they’ll be a hundred years from now, only history can decide.” He had been flattered, on a trip to Bonn in June, 1989, to be greeted by crowds shouting: “Gorbi! Make love, not walls.”

28 He had made a point, during the East German celebrations in October, of reciting a poem at the tomb of the unknown Red Army “liberator” which his audience had not expected to hear:

The oracle of our times has proclaimed unity, Which can be forged only with iron and blood, But we try to forge it with love, Then we shall see which is more lasting.29

He had reassured Krenz, just before the Berlin Wall came down, that “[n]obody could ignore . . . that manifold human contracts existed between the two German states.” And on the morning after the night the gates were opened in Berlin, he recalls wondering “how could you shoot at Germans who walk across the border to meet other Germans on the other side? So the policy had to change.”

30But German reunification was, nonetheless, an unsettling prospect, not just for the Soviet Union but for all Europeans who remembered the record of the last unified German state. This anxiety transcended Cold War divisions: Gorbachev shared it with Jaruzelski, French President François Mitterrand, and even Margaret Thatcher, who warned Bush that “[i]f we are not careful, the Germans will get in peace what Hitler couldn’t get in the war.”

31 The one prominent European who disagreed was West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who surprised everyone by coming out in favor of reunification a few days before the Malta summit. Bush thought he had done so because “he wanted to be sure that Gorbachev and I did not come to our own agreement on Germany’s future, as had Stalin and Roosevelt in the closing months of World War II.”

32Kohl, then, was leading, but only barely because the East Germans themselves—having broken through the wall—quickly made it clear that they would accept nothing less than reunification. Hans Modrow, who had replaced Krenz as prime minister, informed Gorbachev at the end of January, 1990, that “[t]he majority of the people in the German Democratic Republic no longer support the idea of two German states.” The government and party itself, K.G.B. chief Vladimir Kryuchkov confirmed, were falling apart. Confronted with this information, Gorbachev saw no choice: “German reunification should be regarded as inevitable.”

33The critical question was on what terms. East Germany was still a member of the Warsaw Pact, and over 300,000 Soviet troops were stationed there. West Germany was still part of NATO, with about 250,000 American troops on its territory.

34 The Soviet government insisted that it would not allow a reunified Germany to remain within the NATO alliance: it proposed instead neutralization. The Americans and West Germans were equally insistent that the NATO affiliation remain. All kinds of suggestions surfaced for resolving this dispute, even—briefly—the thought that a unified Germany might have dual membership in both NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Thatcher, no friend of unification, nevertheless dismissed this as “the stupidest idea I’ve ever heard of.” “[W]e were,” Gorbachev recalled wistfully, “the lone advocates of such a view.”

35In the end, Bush and Kohl persuaded Gorbachev that he had no choice but to accept a reunified Germany within the NATO alliance. He could hardly respect the East Germans’ determination to dismantle their own state without also respecting the West Germans’ demands to remain a part of NATO. Nor could he deny that there was less to fear from a unified Germany linked to NATO than from one operating on its own. The Americans, in the end, made only one concession to Gorbachev: they promised, in the words of Secretary of State James Baker, that “there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction one inch to the east”—a commitment later repudiated by Bill Clinton’s administration, but only after the Soviet Union had ceased to exist.

36 Gorbachev, for his part, believed that the United States was holding out for NATO membership because it feared, otherwise, that a unified Germany might seek to expel

American troops: “I made several attempts to convince the American President that an American ‘withdrawal’ from Europe was not in the interest of the Soviet Union.”

37What this meant, then, was that Soviet and American interests were converging in support of a settlement that, only months earlier, would have been considered unthinkable: that Germany would reunify, that it would remain within NATO, and that Soviet forces stationed on German territory would withdraw while American forces stationed on German territory would remain. The critical agreement came in a meeting between Gorbachev and Kohl in July, 1990. “We cannot forget the past,” the Soviet leader told his German counterpart. “Every family in our country suffered in those years. But we have to look towards Europe and take the road of co-operation with the great German nation. This is our contribution toward strengthening stability in Europe and the world.”

38 And so it happened that on October 3, 1990—less than a year after the guards at the Bornholmer Strasse crossing point decided, without consulting anyone, to open the gates—the division of Germany that had begun with defeat in World War II finally came to an end.

III.

GORBACHEV by then had been cheered in East Berlin, Bonn, and Beijing, something no previous occupant of the Kremlin had ever managed. But he had also gained a less auspicious distinction: on May 1, 1990, he became the first Soviet leader to be jeered, even laughed at, while reviewing the annual May Day parade from atop Lenin’s tomb in Red Square. The banners read: “Down with Gorbachev! Down with socialism and the fascist Red Empire. Down with Lenin’s party.” And it was all on national television. They were “political hooligans,” Gorbachev sputtered, ordering an investigation. “To have set such a country in motion!” he later complained to his aides. “And now they’re screaming: ‘Chaos!’ ‘The shelves are empty!’ ‘The Party’s falling apart!’ ‘There’s no order!’” It was “colossal” to have achieved all that had been accomplished without “major bloodshed.” But “[t]hey swear at me, curse me. . . . I have no regrets. I’m not afraid. And I won’t repent or apologize for anything.”

39Was it better, Machiavelli once asked, for a prince to be loved or feared?

40 Unlike any of his predecessors, Gorbachev chose love and mostly attained it—but only outside his own country. Within he was eliciting neither love nor fear but contempt. There were multiple reasons for this: political freedom was beginning to look like public anarchy; the economy remained as stagnant as it had been under Brezhnev; the nation’s strength beyond its borders seemed to have shrunken to that of a doormat. And now another issue was looming on the horizon: could the Soviet Union itself survive?

Lenin had organized the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a federation within which the Russian republic, stretching from the Gulf of Finland and the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, was by far the largest. The others included the Ukraine, Byelorussia, Moldavia, the Transcaucasian republics of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia, as well as the central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kirghizia, and Tadzhikistan. After their absorption into the Soviet Union in 1940, the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were added to the list. By the time Gorbachev took power, there were about as many non-Russians as Russians within the U.S.S.R., and the non-Russian republics had achieved considerable cultural and linguistic autonomy—even some capacity to resist political control from Moscow.

41 Still, no one, Russian or non-Russian, saw any serious possibility of the country breaking up.

It is difficult, though, to compartmentalize reform. Gorbachev could hardly call for

perestroika and

glasnost’ within the Soviet Union, or for letting the East Europeans and the Germans do it “their way,” without encouraging non-Russian nationalities who had never fully accepted their incorporation into the U.S.S.R. These included chiefly the Baltic and Transcaucasian republics, where pressures quickly began to build for still greater autonomy, even independence. A Lithuanian professor stated the logic in a meeting with Gorbachev early in 1990:

[T]he national revival [is] engendered by perestroika. Both are intertwined . . . After the [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] resolved to base our political life on democracy, we in the Republic have considered it, first and foremost, as a proclamation of the right to self-determination. . . . [W]e are convinced that you are sincere in wishing all people well and understand that you cannot make a people happy against its will.

Gorbachev found this “an indisputable argument.” But “while admitting the possibility of secession in principle, I had hoped that the development of economic and political reform would outpace the secession process.”

42 That, too, was a faulty prediction.

For as politics opened up while prosperity lagged behind, it became hard to see what benefits a state like Lithuania got from being part of the Soviet Union. The Lithuanians resented how that had come about—Hitler and Stalin had arranged their annexation in the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact. They followed closely what was happening now in Germany and Eastern Europe. Whatever lingering doubts there were disappeared in January, 1991, when Soviet troops in Vilnius fired on a crowd of demonstrators, and on February 19th, the Lithuanians decisively voted for independence. Much the same sequence of events occurred in Latvia and Estonia. Gorbachev, still hoping for love, was not inclined to resist.

43But if the Baltics seceded, why could the Transcaucasian republics not do the same? Or the Moldavians? Or even the Ukrainians? These were the questions confronting Gorbachev in the spring of 1991, and he had no answer for them. “[A]lthough we were slaying the totalitarian monster,” Chernyaev recalled, “no consensus emerged on what would replace it; and so, as perestroika was losing its orientation, the forces it had unleashed were slipping out of control.”

44 In June, the biggest republic of them all, the Russian, elected its own president. He was Boris Yeltsin, a former Moscow party boss and now Gorbachev’s chief rival. The contrast could not be missed, because for all of his talk of democracy Gorbachev had never subjected himself to a popular vote. Another contrast, less evident at the time, would soon become clear: Yeltsin, unlike Gorbachev, had a grand strategic objective. It was to abolish the Communist Party, dismantle the Soviet Union, and make Russia an independent democratic capitalist state.

Yeltsin was not a popular figure in Washington. He had a reputation for heavy drinking, publicity seeking, and gratuitous attacks on Gorbachev at a time when Bush was trying to support him. He had even once picked a fight over protocol in the White House driveway with Condoleezza Rice, the president’s young but formidable Soviet adviser—which he lost.

45 By 1991, though, there was no denying Yeltsin’s importance: in “reassert[ing] Russian political and economic control over the republic’s own affairs,” Scowcroft recalled, “he was attacking the very basis of the Soviet state.” It was one thing for the Bush administration to watch Soviet influence in Eastern Europe disintegrate, and then to push German reunification. It was quite another to contemplate the complete breakup of the U.S.S.R. “My view is, you dance with who is on the dance floor,” Bush noted in his diary. “[Y]ou especially don’t . . . [encourage] destabilization. . . . I’m wondering, where do we go and how do we get there?”

46Bush arrived in Moscow on July 30th to sign the START I arms control treaty, now almost wholly overshadowed by the course of events. He and Gorbachev spent a relaxed day at the Soviet leader’s

dacha. “I had the impression,” Chernyaev recalled, “that I was present at the culmination of a great effort that had been made along the lines of the new thinking. . . . [I]t never resembled the ‘tug of war’ of the past.” Bush shared the sense, but by the end of the summit had noticed that Gorbachev’s “ebullient spirit was gone.”

47 On the way home, the president stopped in Kiev to address the Ukrainian parliament. He tried to help Gorbachev by praising him and then reminding his audience:

Freedom is not the same as independence. Americans will not support those who seek independence in order to replace a far-off tyranny with a local despotism. They will not aid those who promote a suicidal nationalism based upon ethnic hatred.

With that, though, he lost his audience. “Bush came here as a messenger for Gorbachev,” one Ukrainian grumbled. “[H]e sounded less radical than our own Communist politicians. After all, they have to run for office here . . . and he doesn’t.” The crowning blow came when

New York Times columnist William Safire denounced Bush’s “chicken Kiev” speech. It was also, arguably, a low blow, but one that captured the administration’s ambivalence as it contemplated the possibility of life without the U.S.S.R.

48“Oh Tolya, everything has become so petty, vulgar, and provincial,” Gorbachev sighed to Chernyaev on August 4th, just before leaving for his summer vacation in the Crimea. “You look at it and think, to hell with it all! But who would I leave it to? I’m so tired.”

49 It was, for once, a prescient observation, for on August 18th all of Gorbachev’s communication links were severed and a delegation of would-be successors arrived to tell him that he was under house arrest. His own colleagues, convinced that his policies could only result in the disintegration of the Soviet Union, had decided to replace him.

Three chaotic days followed, at the end of which three things had become clear: first, that the United States and most of the rest of the world regarded the coup as illegitimate and refused to deal with the plotters who had carried it out; second, that the plotters themselves had neglected to secure military and police support; and finally, that Boris Yeltsin, by standing on a tank outside the Russian parliament building and announcing that the coup would not succeed, had ensured its failure. Gorbachev could take little comfort in this, though, because Yeltsin had now replaced him as the dominant leader in Moscow.

50Yeltsin quickly abolished the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and confiscated all its property. He also disbanded the Congress of People’s Deputies, the legislative body Gorbachev had created, and installed in its place a council composed of representatives from the remaining republics of the U.S.S.R. It in turn recognized the independence of the Baltic States, which led the Ukraine, Armenia, and Kazakhstan to proclaim their own. Gorbachev’s authority evaporated as Yeltsin repeatedly humiliated him on national television. And on December 8th, Yeltsin signed an agreement with the leaders of the Ukraine and Byelorussia to form a “Commonwealth of Independent States.” He immediately called Bush: “Today, a very important event took place in our country. . . . Gorbachev does not know these results.” The president saw the significance immediately: “Yeltsin had just told me that he . . . had decided to dissolve the Soviet Union.”

51“What you have done behind my back . . . is . . . a disgrace!” Gorbachev protested, but there was nothing he could do: he was without a country. And so on December 25, 1991—two years to the day after the Ceauşescus’ execution, twelve years to the day after the invasion of Afghanistan, and just over seventy-four years after the Bolshevik Revolution—the last leader of the Soviet Union called the president of the United States to wish him a merry Christmas, transferred to Yeltsin the codes needed to launch a nuclear attack, and reached for the pen with which he would sign the decree that officially terminated the existence of the U.S.S.R. It contained no ink, and so he had to borrow one from the Cable News Network television crew that was covering the event.

52 Determined, despite all, to put the best possible face on what had happened, he then wearily announced, in his farewell address, that: “An end has been put to the ‘Cold War,’ the arms race, and the insane militarization of our country, which crippled our economy, distorted our thinking and undermined our morals. The threat of a world war is no more.”

53Gorbachev was never a leader in the manner of Václav Havel, John Paul II, Deng Xiaoping, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Lech Wałęsa—even Boris Yeltsin. They all had destinations in mind and maps for reaching them. Gorbachev dithered in contradictions without resolving them. The largest was this: he wanted to save socialism, but he would not use force to do so. It was his particular misfortune that these goals were incompatible—he could not achieve one without abandoning the other. And so, in the end, he gave up an ideology, an empire, and his own country, in preference to using force. He chose love over fear, violating Machiavelli’s advice for princes and thereby ensuring that he ceased to be one. It made little sense in traditional geopolitical terms. But it did make him the most deserving recipient ever of the Nobel Peace Prize.

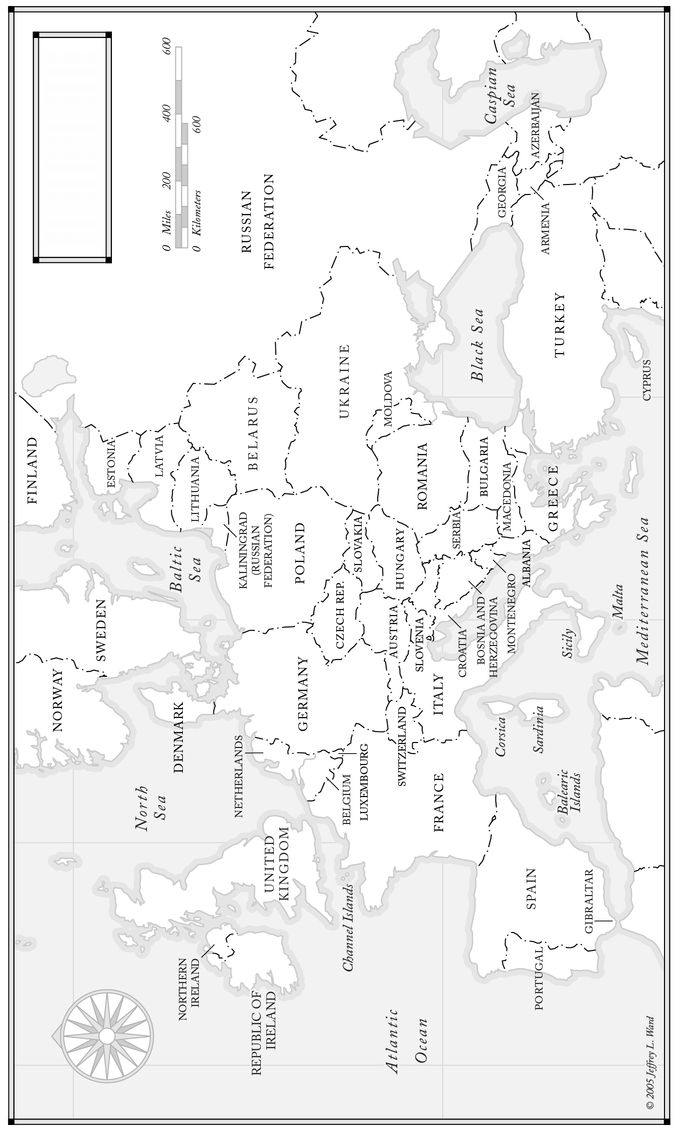

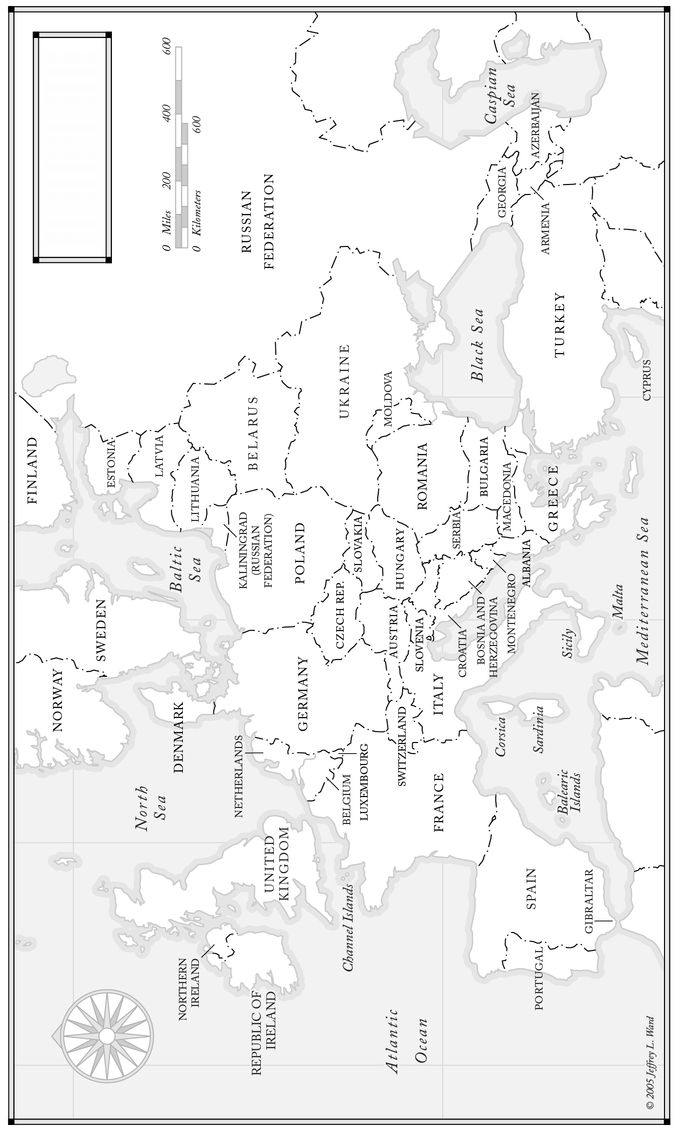

POST COLD-WAR EUROPE