Chapter Two

Mining Internal Data Is Looking at the Past

In 1977 a college dropout named Larry Ellison founded a start-up which he called Software Development Laboratories. In his previous job at Ampex, an electronics company, he had read a paper by the British computer scientist Edgar Frank Codd, who, while working for IBM in 1970, had written ‘A Relational Model for Large Shared Data Banks’. Ellison worked on a number of projects for Ampex, including a database for the CIA, which he called Oracle, the name which he eventually gave his company.

The business, based in Redwood Shores, California, would come to dominate the database and enterprise software market commonly referred to as Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP). Today Oracle is one of the world’s most powerful tech companies. For its 2015 fiscal year Oracle posted revenue of $38.2 billion and profits of $10 billion.1

Oracle’s founder, Larry Ellison, is not as famous as Apple’s Steve Jobs or Microsoft’s Bill Gates, but he has shaped the world we live in as much as either of them. Before Oracle, company data was buried in silos and hard to access. Some data was stored in mainframes or typed and handwritten on paper in binders. Most of the data was not in a usable format, making it impossible to analyse for meaning and insight. The advent of ERP systems meant that this internal data was slowly digitized. Indeed, by 2005, 80 per cent of Fortune 500 companies had installed, or were in the process of implementing, a company-wide ERP system.2

As the market started to demand software customized for different functional needs – such as customer relationship management (CRM), finance, human resources (HR), supply chain and business intelligence (BI) – Ellison embarked on an unprecedented decade-long acquisition spree to the tune of $35 billion. The acquisitions added expertise in workflow, business, logic, visualization and reporting on top of Oracle’s database and made it the most trusted enterprise software company in the world. In Chapter 13 we will see how history repeats itself and will study these acquisitions in more detail.

Today we’re so used to enterprise software that it’s easy to forget that it has only been around since the mid-1990s. Today executives are completely reliant on their ERP system for understanding their business performance. What is our client retention in Europe like? What are the latest productivity numbers per salesperson? What is the profit contribution of our newest business division? Where is our growth coming from today? How do we get the largest return on investment? The answers to all of these questions can be found in the ERP systems.

Larry Ellison’s Oracle has spearheaded an entire new industry of staggering proportions. Global annual corporate IT spend, including servers, devices, enterprise software and professional services, reached $3.52 trillion in 2015, according to the technology research company Gartner.3 To put this number in perspective, that is bigger than the global car industry!

If Steve Jobs revolutionized computing for consumers, then Larry Ellison did the same thing for enterprise. As of January 2016 Oracle employs 133,000 people and is run by 98 per cent of the Fortune 500 companies.4 For more than forty years Ellison has been one of Silicon Valley’s most influential individuals. Beyond Oracle, he has played an instrumental role in a number of Silicon Valley’s success stories, including Salesforce and NetSuite, both leading cloud-based enterprise software companies.

In January 2016 Ellison was ranked the fifth-wealthiest person in the world by Forbes Magazine, with a net worth of $54 billion, dwarfing the founders of Facebook, Google and Amazon, and eclipsed only by Bill Gates among IT entrepreneurs.

Larry Ellison built his wealth on changing the way companies make decisions. His software transformed the internal world of companies from a collection of inefficient systems that didn’t communicate to a streamlined ERP system where information from all parts of the company could be combined into rigorous analysis and enable thoughtful, data-driven decisions.

Internal data is lagging data

The introduction of ERP systems like Oracle clearly represented a very valuable upgrade from the old paradigm, where executives couldn’t access the internal data in an efficient way.

The obvious limitation with ERP systems is that they contain lagging data based on historical events. The figures in financial reports are the end-result of activities and investments that took place in the past. It takes months and sometimes quarters to ramp up a new salesperson. In many industries it takes years of investment to develop and bring a product to market. In our ERP system we can probe and analyse our data down to fine-tuned granularity, but, for all our efforts, the only insights we will find will be historical.

A key thesis of this book is that we need to be careful with how we use our ERP software. Over-reliance on these systems can be dangerous and create a world-view limited by the information that can be found in our internal systems. It is easy to be swayed by captivating graphs and analysis, but we have to bear in mind that our ERP system can only answer a few of the questions we have to ask ourselves when making important decisions.

The current situation is not present in the figures we find in our ERP system. Neither is recent investment by our competitors and recent industry development. For all its persuasive rigour, internal data has clear limitations when making decisions about the future. The following example illustrates this well.

In 2012, for the third year running, Meltwater’s Canadian office performed badly, in stark contrast to the performance of the rest of the company. We lost money, we didn’t grow and retention of people was the worst in the company.

In January 2013 we had a heated discussion at a Meltwater board meeting. Because of these poor figures, our external board members were pushing hard to close down in Canada and invest our dollars in other markets instead. After all, it was our smallest business unit and insignificant. I argued that there was nothing wrong with the Canadian market. The competitive landscape was attractive, and its maturity was well above other markets we thrived in. I argued that this was an internal issue because we did not have the right management in place. I presented an alternative strategy with new management and a doubling down on our investments.

Eventually the board supported my plan, and within three years Canada leapt from the twentieth and worst-performing business unit within Meltwater to the fifth-best, entering 2016 with an impressive 55 per cent annual growth rate.

At the Meltwater board we talk about this incident from time to time. We use it to remind ourselves that there is only so much that can be accomplished by poring over historical data – partly because history doesn’t necessarily predict the future, and partly because there is only so much that can be captured in a spreadsheet. Running a company is a complex endeavour. The biggest factor is always your people. Their confidence, enthusiasm and conviction are always the most important factors in your future business performance.

The insular bias

Another problem with ERP systems is that you study your company’s internal data in isolation. You don’t get current information about what your competition is doing. You don’t get reliable information about industry trends. You create a world-view based on what you see through the lens of your historical operational efficiency.

Internal analyses in isolation can create a misguided understanding of your competitive situation. Say the price you are able to get for your product in the French market drops over a twelve-month period. Is this due to weaker demand in the market, increased competition or lower confidence in your French sales organization? From just looking at your internal data it would be very difficult to know. And that is a big problem because without properly understanding the root cause of the issue it is hard to take appropriate action.

More often than not, management don’t have – or don’t make the effort to get – third-party data to help them interpret their internal data. Instead they are influenced by preconceived ideas or beliefs that may or may not be entirely accurate.

This insular bias is fortified as analysis travels up through the organization. When a report reaches the company board, the underlying facts have been analysed, structured and packaged through many layers of management. At each level, data is curated to support the narrative each level of management wants to communicate. Some data will be amplified; other data will be muted. As a report travels upwards through a company, there is a tendency for the facts to become weaker and the narrative stronger.

Being too internally focused is dangerous, given the pace with which the world is changing today. Forty per cent of the Fortune 500 companies in the year 2000 were gone ten years later.5 This destructive development seems to accelerate. In 2014 Dennis Hanno, Dean of Babson School of Business in Wellesley, Massachusetts, predicted that half of the Fortune 500 companies at that time would also be gone within a decade.

There are many tales about great companies that have crumbled because they were not able to adapt quickly enough. This is not because there was a lack of data showing their steady decline. Their problem lay with fighting preconceived beliefs and breaking through their internal bias.

The rise and fall of BlackBerry

When BlackBerry’s joint CEOs, Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie, first saw the iPhone in January 2007, they were convinced that the device didn’t pose a threat to their mobile services company, according to Losing the Signal: The Untold Story behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry, by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff.6 They considered their own mobile devices to be a far better proposition for business users: the iPhone was more expensive, had a much shorter battery life, a 2G radio and a touchscreen keyboard. How many business users would go for that? They’d be on a sales call in Cleveland and by the time they were out of the rental car park they’d need to recharge.

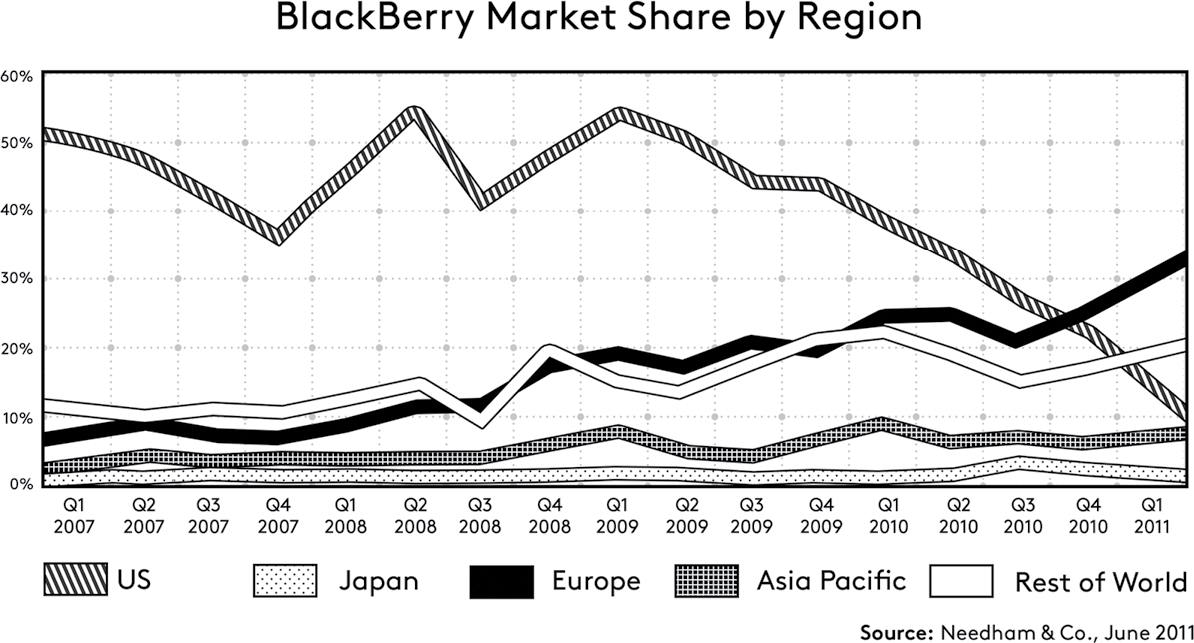

And in the short term BlackBerry’s executives were right. The Canadian phone producer grew steadily by delighting the professional business users with its user-friendly keyboard, integrated corporate security and innovative messaging system, called BBM. By Q1 2009 BlackBerry had become standard for the lucrative business segment, with a market share of 55 per cent in the US and 20 per cent globally.7

During the next three years, despite tremendous growth, the market was running away from the Canadian handset manufacturer. People had moved on to a new generation of smartphones with a touch screen instead of a keyboard.

In Q1 2012 growth took a brutal hit. Delays in new product releases were cited as one of the reasons for this, but it was clear from the stagnating user growth that the consumer had developed a strong appetite for competing products. Q1 2012 revenue was $2.8 billion, down 33 per cent from the previous quarter and down 43 per cent from the year before. So worrying was the outlook that the new CEO of RIM (the company that produces the BlackBerry), Thorstein Heins, laid off 4,500 people, nearly 40 per cent of the workforce. ‘There is nothing wrong with the company as it exists right now,’ he insisted in an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Radio Corp.8 ‘Rather, we believe RIM is a company at the beginning of a transition that we expect will once again change the way people communicate. […] As we prepare to launch our new mobile platform, BlackBerry 10, in the first quarter of next year, we expect to empower people as never before.’

Thorstein Heins’s predictions didn’t come true. BlackBerry’s development took instead a nose-dive. In September 2013 BlackBerry announced a second-quarter net loss of close to a billion dollars owing to poor sales of one particular model, the Z10.9 BlackBerry was at this point haemorrhaging users and market share. By the end of the year the market share had plummeted to 0.6 per cent globally. The once admired innovation leader in the smartphone sector had been wiped out.

The implosion of the Canadian telco and handset manufacturer is one of the most dramatic corporate demises of recent times. The speed at which the company moved from dominating the corporate mobile phone market to fighting for its very existence took both insiders and market watchers by surprise.

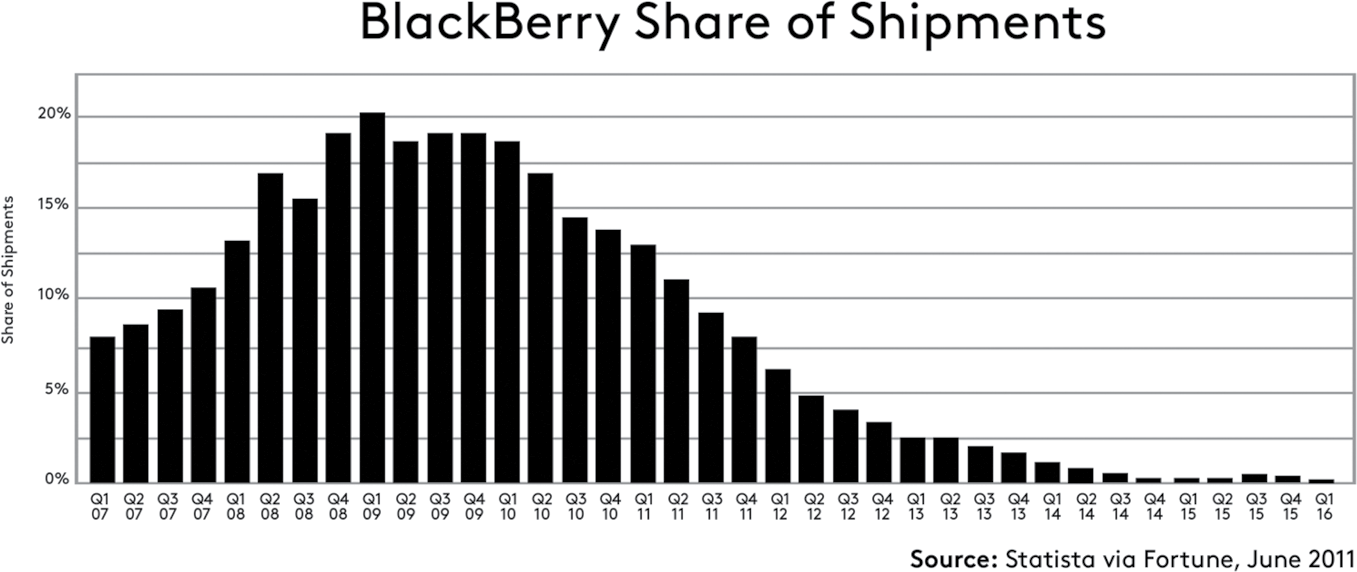

The tale of BlackBerry is an excellent example of the limitations of internal company data. From the time the first iPhone was unveiled in 2007 to the fatal quarterly report for Q1 2012, BlackBerry’s users grew almost tenfold (!), from 8 million to 77 million. Equally impressive is the quarterly revenue growth. BlackBerry hit $1 billion in quarterly revenue in Q1 2007 and shot up to $5.5 billion by Q1 2011, growing by between 40 and 100 per cent year-on-year in most quarters.

Looking at BlackBerry’s internal figures alone, one would think that BlackBerry was going from one victory to another. It turns out the internal data didn’t tell the whole story. By definition, internal data is biased; it contains rich data about your company, but no direct information about the market and your competitors.

Studying the market share development, the picture looks quite different. Now it is obvious that the problems had started to appear as far back as Q1 2009. Up until that point BlackBerry had been seeing strong growth and a steady increase in market share, peaking at 20 per cent globally, but from this point the development was very concerning. US market share dropped from 55 per cent in Q1 2009 to 12 per cent in less than two years. Globally, the drop in market share was less rapid, but within three years it had plunged to obscurity internationally too.

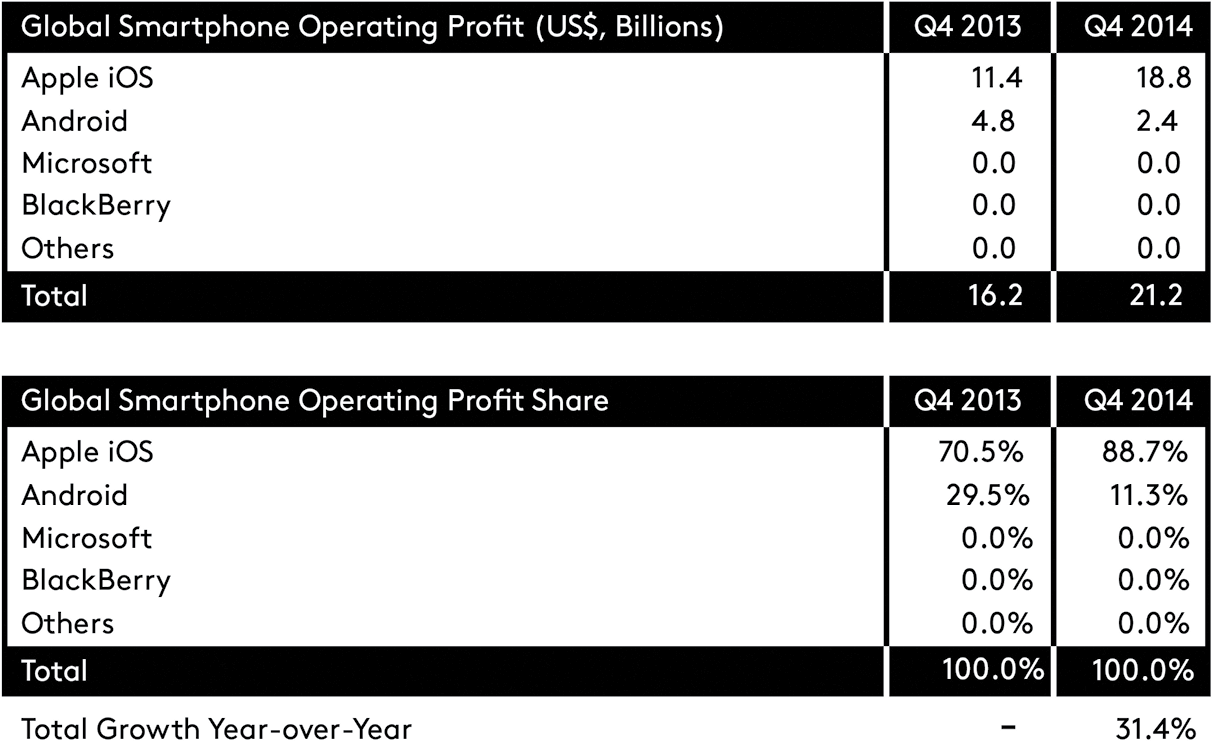

A further study of the different handset makers’ individual faith paints an even more nuanced picture. Nokia (Symbian) and BlackBerry (RIM) were the big losers, whereas Apple and the Android phones are the winners. Android won the volume game, with a growth from about 10 per cent in 2010 to an incredible 80 per cent in 2013. When it comes to profitability, though, industry analysts agree that Apple is dominant, in spite of being consistently at a relatively modest market share of 15 to 20 per cent.

According to analyst firm Strategy Analytics, Apple’s iPhone secured $11.4 billion profit for Q4 2013, which is more than 70 per cent of the profitability of the entire industry. One year later, in Q4 2014, Apple had increased their iPhone profit to $18.8 billion and a staggering 89 per cent of the total profit pool.

The demise of BlackBerry is complex, but at its heart the company remained too focused on what it used to excel at – physical keyboards and security – and was not able to adapt quickly enough when the market changed. In spite of impressive growth, the company was losing market share because the competitors were growing faster. In the end BlackBerry would be reduced to irrelevance.

Competitors fuelled their growth by catering to the new generation of smartphone users better. BlackBerry didn’t embrace the new user demands, such as browsing the internet and apps for consuming media and services. The BlackBerry browser was a miserable online experience, and their app effort, when it arrived, was too little and too late. BlackBerry were stuck in their focus on creating a phone for productivity while the competition, spearheaded by Apple, appealed to the user’s emotional side with slick design, a lush high-resolution colour screen and an innovative touch interface unlike anything anyone had seen before.

RIM’s chief technology officer, David Yach, admitted that the company didn’t anticipate iPhone’s popularity. He told The Wall Street Journal: ‘By all rights the product should have failed, but it did not. I learned that beauty matters […] RIM was caught incredulous that people wanted to buy this thing.’10

BlackBerry relied too much on historical success recipes and grossly underestimated its competition. Its staggering revenue growth through 2011 gave the company a false sense of confidence, and it failed to acknowledge that its market share had plummeted from its peak in Q1 2009. From its 2011 record revenue BlackBerry dropped more than 80 per cent in revenue within three years and would never recover. It failed to adjust to changing market demands. BlackBerry’s historical success with the keyboard interface created an internal bias that drove the company off a cliff.

At the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 Lord Nelson, then a vice-admiral in the British fleet, leading the main attack against the Danes, is famously said to have put his telescope to his blind eye to avoid seeing flags signalling him to withdraw. Nelson’s mind was set, and he refused to be distracted from his course.

For all its promise of converting corporate decision-making from the realm of gut feeling to a rigorous discipline based on facts, enterprise software has inherent weaknesses. The internal data captured represents only a narrow slice of information influencing your company’s future. The insights extracted from these numbers will always suffer from internal biases and follow a subjective narrative distilled by layers of managers and executives.

In the rest of the book we will discuss the biggest blind spot in contemporary decision-making and how a new decision paradigm is necessary in order to embrace a new digital reality. This will in turn give rise to an entirely new software category that will transform executive decision-making just as much as the introduction of enterprise software did in its time.