Chapter Five

The Value of External Data

Internal biases and misconceptions come in all shapes and sizes. We all have them. The inner workings of every company are full of them. Some misconceptions are innocent. Others are very serious. In this chapter we are going to learn about a misconception that cost society trillions of dollars and millions of Americans their homes. It is a strong reminder of how dangerous internal biases and misconceptions can be, and how important it is always to consult external data.

The 2016 Oscar-winning film The Big Short, starring Christian Bale, Brad Pitt, Steve Carell and Ryan Gosling, tells the story of four men whose analyses of public data around lending behaviour in 2003–4 enabled them to see what nobody else could see.

Bale played Michael Burry, a hedge fund manager at Scion Capital who predicted the financial crisis as early as 2005. In order to understand how subprime mortgage bonds worked, Burry scanned hundreds, and read dozens, of prospectuses for different mortgage bonds. Each one came with its own 130-page guide, and, according to Lewis, Burry was the only person, aside from the lawyers who drafted them, to read them in detail. Burry used the information to bet against the housing market, earning huge returns for his fund and clients.

By the middle of 2005, over a period in which the broad stock-market index had fallen by 6.84 per cent, Burry’s fund was up 242 per cent, and he was turning away investors.1 By 30 June 2008 any investor who had stuck with Scion Capital from its beginning, on 1 November 2000, had a gain, after fees and expenses, of 489.34 per cent. (The gross gain of the fund had been 726 per cent.) Over the same period the S&P 500 returned just a bit more than 2 per cent.

The value of external data in correcting insular bias

Burry was making a fortune betting against the housing market. He saw something that nobody else had seen. His secret superpower was simple – he took the time to read the mortgage prospectuses. This was freely available information for everyone to study. It turned out nobody else bothered.

The financial instruments that Burry bet against were known as subprime mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO). The conventional wisdom was that these instruments were designed by the best risk experts in the industry and in such a way that they could not fail. These instruments were given top AAA credit ratings, so-called ‘immune-from-default’ ratings, by the rating agencies and became highly sought-after because of their high returns. From 2004 to 2006 the US subprime lending market grew from 8 per cent to 20 per cent of the mortgage market, and it peaked at a staggering $1.3 trillion in March 2007.2

Their top credit ratings were based on the assumptions that house prices would rise and that mortgage delinquency would stay at historical levels. When reading the mortgage prospectuses, Burry realized that this was wrong. The demand for subprime instruments had lowered the requirements for who were given mortgages. He discovered an alarming trend in late payments, and he realized that delinquency would go way up compared with historical levels and in the process exert dangerous pressure on house prices.

He realized that the whole world was counting on preconceived beliefs that would not hold true going forward. Everyone was wrong, and the economy was about to come crashing down. He double-checked and triple-checked, but came to the same conclusion every time.

Burry’s view was so contrarian at the time that Goldman Sachs had to create a new instrument to make it possible for him to short the market. The notion of shorting AAA mortgage bonds was simply preposterous and had never been done before. In a memorable scene from the film Burry’s last ask in his negotiation with Goldman Sachs is for collateral in case Goldman Sachs should become insolvent. Burry genuinely feared that banks could go under and didn’t trust the solvency even of Goldman Sachs. Before Burry’s predictions came true, he also suffered a massive revolt from his investors, who wanted their money back because they thought he had gone mad.

As we know, Burry’s predictions did come true. By October 2007 approximately 16 per cent of subprime adjustable rate mortgages were either ninety days overdue or the lender had begun foreclosure proceedings: roughly triple the rate of 2005. By January 2008 the delinquency rate had risen to 21 per cent, and by May that year it was 25 per cent. Between August 2007 and October 2008 nearly a million US residences completed foreclosure, driving house prices down by nearly 30 per cent.

The subprime crisis in 2007 and 2008 had severe, long-lasting consequences for the US and European economies. The US entered a deep recession, with nearly 9 million jobs lost during 2008 and 2009 – roughly 6 per cent of the workforce. By early November 2008, the US stock market was down 45 per cent from its 2007 high. The crisis would affect everyone. In an article in Foreign Affairs, investment banker and former Deputy Secretary of the Treasury in the Clinton administration Roger C. Altman estimates that between June 2007 and November 2008 Americans lost more than a quarter of their net worth.3

The crisis in the US also spread to Europe. Several countries, such as Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Cyprus, were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks and had to seek help from other Eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Between 2008 and 2012 Europe also struggled with high unemployment and severe banking losses estimated at €940 billion.4

In an ‘op-ed’ for The New York Times on 4 April 2010 Michael Burry, who by now had risen to global fame, argued that anyone who studied the financial markets carefully in 2003, 2004 and 2005 could have recognized the growing risk in the subprime markets.5 Burry has since said: ‘I don’t go out looking for good shorts. I’m spending my time looking for good longs. I shorted mortgages because I had to. Every bit of logic I had led me to this trade and I had to do it.’6

By analysing publicly available information, Burry discovered a global misconception that would cause one of the largest financial crises in modern history.

Clearing up the mess

The subprime crisis brought banking giants across the world to their knees. There were genuine fears that the international banking system could collapse, that everyone would lose their money and that the world would tailspin into financial Armageddon.

I didn’t understand much of what was going on myself, but I know investment bankers and Harvard graduates who panicked and moved their savings into gold and remote farmland: gold because they feared money would lose its value, and remote farmland to escape social unrest and to grow food. People close to the action were really scared.

Governments around the world had to rescue troubled banks and prevent their economies from collapsing. This happened in the US, UK, Belgium, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. All over the globe people started to lose confidence in their banks and worry about their savings. As soon as a bank showed a sign of weakness, there was a run on it as people tried to get their money out.

When Northern Rock, the UK’s fifth-largest mortgage lender, announced a need for governmental financial support on 14 September 2007, panic broke out and £2 billion, about 10 per cent of the total bank deposits, was withdrawn within forty-eight hours.7 In one incident police were called to the branch in Cheltenham when two joint account holders barricaded the bank manager into her office after she refused to let them withdraw £1 million from their account.8 Their money was held in an internet-only account, which they were unable to access after the Northern Rock website crashed owing to the volume of customers trying to log on. On 22 February Northern Rock was taken into state ownership in order to save it from collapse. In the process, all Northern Rock shareholders were wiped out, but Northern Rock customers’ deposits were saved.

At the height of the crisis I became concerned about the health of the US banks myself. To safeguard Meltwater, I instructed all our US funds to be transferred out of the US and out of the US bank system. We wired our excess cash to a bank account we had in the Netherlands. It was not a panic move, but I didn’t want to take any risks. A few days later our Dutch bank also announced huge subprime exposures, and this time we moved our money to Norway. My sleepy little home country tucked away in the cold outskirts of Europe turned out to be one of the safer places to keep money during those uncertain times.

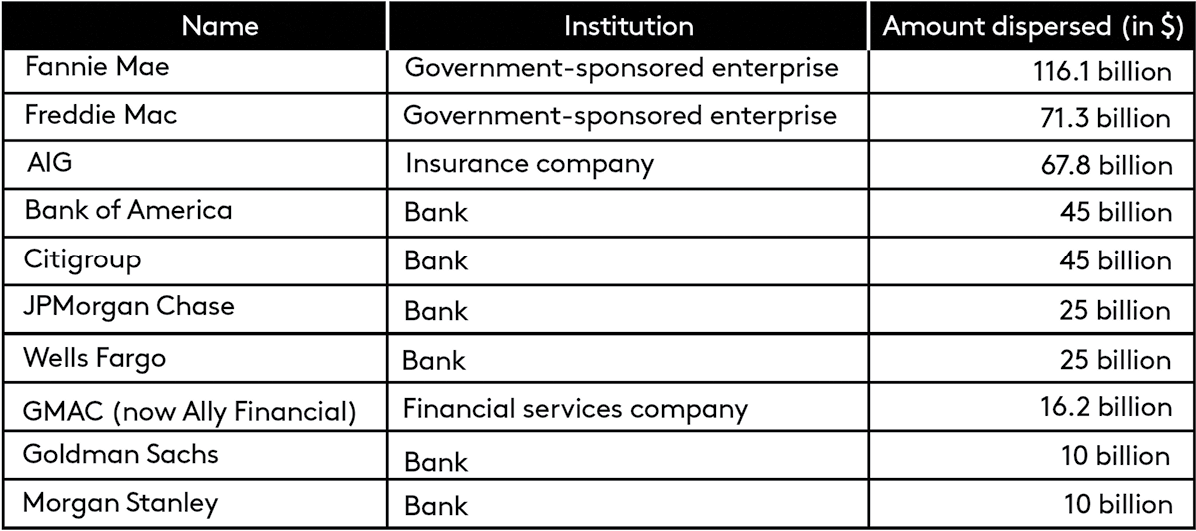

The subprime crisis originated in the US, and it was there that the hurt was most keenly felt. On 3 October 2008 a law was passed in Congress by which $700 billion of emergency liquidity was secured to save US banks from going under.9 The recipients were all the largest banks in the US, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Bear Stearns and American Express. The online outlet Propublica.org has developed an excellent feature called the Bailout Tracker, which tracks every dollar and every recipient. In total forty-three banks and insurance companies were saved by the bail-out. Two notable companies, Bear Stearns and AIG, were rescued at the eleventh hour.

Bear Stearns, the eighty-five-year-old investment bank, had famously not laid off a single person during the Great Depression of the 1930s, yet the subprime crisis brought the company to its knees. By the end of 2007 it was leveraged at a ratio of 35.6 to 1. On 16 March 2008 the Federal Reserve Bank of New York forced Bear’s CEO, Alan Schwartz, to capitulate and sell the company to JPMorgan Chase for $10 per share, a 92.5 per cent discount on the pre-crisis fifty-two-week high.10 Fourteen thousand employees, who owned around 30 per cent of the shares, lost $20 billion in the deal. But the bank was saved, and they kept their jobs.

AIG, the world’s biggest insurer, was deeply entangled in the subprime crisis, insuring a large part of the subprime instruments traded in the US as well as internationally. On 16 September 2008 the unthinkable happened. The eighty-eight-year-old company, trusted around the world for providing protection for individuals and companies, was fighting for its survival and needed protection from bankruptcy. In exchange for $85 billion of taxpayers’ money, the US government took a 79 per cent ownership stake in the company.11 It was a horrible loss for all AIG shareholders, but the alternative was much worse.

The fall of Lehman Brothers

One of the most infamous casualties of the subprime crisis was the revered Lehman Brothers. Lehman Brothers was founded in Alabama in 1850 by three siblings who had emigrated from Germany. The bank started out as a commodity trader but grew to become the fourth-largest investment bank in the US, eclipsed only by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch.

For the fiscal year 2007 Lehman Brothers reported record profits of $4.2 billion on revenue of $19.3 billion.12 A few months later, in September 2008, it was all over for the 158-year-old company, which had weathered two world wars and countless financial crises of the past, such as the railroad bankruptcies of the 1800s, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Russian debt default of 1998 and the dotcom bubble of 2000. When the subprime crisis brought Lehman down, it employed 26,200 people.

Lehman’s collapse was a seminal event that greatly intensified the 2008 crisis. In the month of October 2008, $10 trillion of market capitalization was wiped off global equity markets, the biggest monthly decline on record at the time.

In an excellent piece in New York magazine, published in the heat of the global financial meltdown in November 2008, the writer Steve Fishman scrutinized the then recent collapse of Lehman Brothers.13 He examined the role of the CEO, Dick Fuld, a man known throughout Wall Street for his ability to intimidate both colleagues and competitors. While the downfall of Lehman Brothers was highly complex, Fishman identifies the fact that Fuld, and other senior executives, were out of touch with the outside world as one of the elements that led to the bank’s demise.

On 9 June, close to three months after the collapse of Bear Stearns, Lehman released its second-quarter earnings statement, declaring a $2.8 billion loss.14 The company assumed that another announcement, one that had been timed to coincide with the earnings statement, would ease the situation. It didn’t. Despite announcing that it had secured $6 billion in new investment, Lehman’s stock dropped 54 per cent down on the year.

Fishman quotes an unnamed executive at Lehman Brothers who described the mistake as a direct result of the senior management’s insular approach. ‘The problem was that not many people were dealing with the outside world. Dick [Fuld] didn’t talk to [anyone] outside, Joe [Gregory, Lehman President] didn’t, the heads of businesses didn’t,’ the executive is quoted as saying. ‘So no one had had a sense of how badly the news would be received.’

‘The environment had become so insular,’ said another former executive. ‘Fuld okayed decisions, but Gregory packaged material so that the choice was obvious. And the executive committee offered no counterweight.’

The misconceptions at the heart of the subprime crisis were catastrophic. The consequences of trusting the toxic subprime instruments ripped through the global banking industry and threatened the existence of almost every bank that people could name. What would have happened if governments across the world hadn’t come to the rescue? What would have happened if the banks had gone under and deposits of millions of people and companies had been lost? The consequences would have been devastating: insolvency, bankruptcy and unemployment. The absurdity of the situation is almost hard to fathom.

The root cause of the subprime crisis was the misconception that the sophisticated subprime instruments designed to insulate against risk could not fail. When credit rating agencies such as Standard and Poor’s gave their stamp of approval with a Triple A rating, nobody bothered to read the ‘fine print’.

The most shameful thing about the financial crisis was that it could have been avoided if people had bothered to read the publicly available information. Burry was the only one who did. The lessons learned from the subprime crisis are many. One key point that stands out is that established biases and misconceptions can be corrected by consulting hard facts and external data.

|

Scan the code using the companion app for more case studies and video interviews on this topic. Download at OutsideInsight.com/app. |

| For further reading visit OutsideInsight.com. |