Roses

IN MARCH 2000 I received a call from my sister Marjon. She told me Aunt Rosie had passed away. An official from the city of Stockholm had contacted her after finding her address among Rosie’s papers. He told her that Rosie had died at home a couple of months earlier and that he had been looking for family members for quite some time. The fact that Rosie had no children hadn’t made it any easier. He had also spoken to her husband Elon’s family. Elon had died in 1967. After some happy years of marriage, Elon started to suffer from depression, which led to heavy drinking. One morning he was found dead in the snow. When he lost his job, Rosie supported both of them. Though their relationship had deteriorated, she considered it her duty to look after him. After Elon, Rosie appeared to have had other serious relationships, one with a bank manager from Stockholm, another with a hospital director from Nuremberg, but she never remarried. In the absence of children, it appeared that we were her closest family.

Marjon, my brother René, and I decided to go to Stockholm to pay our respects and to make whatever arrangements were needed. My oldest daughter, Myra, who was curious about her great-aunt and had been planning to visit her with me in the spring of 2000, joined us.

A week later we flew to Sweden and went directly from the airport to Rostock Crematorium in the east of the city. A clergyman directed us in broken English to a small chapel. Between two burning candles we found an urn containing Aunt Rosie’s ashes. He left us alone. Silence engulfed us. While we knew in advance that we would be collecting her ashes from the crematorium, we were still caught off guard, making the silence even more intense.

It was time to go. The official who had been in touch with us was waiting. I took the urn and put it in my backpack. Quickly, we walked to the city hall. We had to hurry because it closed in an hour, and then the weekend began. It was strange to walk with Aunt Rosie on my back. The blood rushed to my head, and I broke into a cold sweat. We arrived at the city hall just in time, and the formalities were quickly taken care of. I arranged to take the ashes with me to the Netherlands, signed the relevant papers, and received the key to Rosie’s apartment. We planned to take a look over the next few days and decide what to take with us. It wouldn’t be much since we had weight restrictions on the plane. The official promised to have the rest of Rosie’s property cleared from the apartment and the proceeds donated to charity. Before we finished he asked me what the number tattooed on Rosie’s arm meant. I wasn’t in the mood to talk about it, so I told him I didn’t know.

Rosie’s apartment was just as I remembered it. We placed the urn on the table, opened the doors to the balcony, and looked out over Mälaren Bay. The weather was tranquil, frosty, and hushed. We were no longer in a hurry. The sun began to set, and we looked for candles, then lit them on either side of Rosie. She was home again.

The following morning I started to search for papers and photos. The postcard with Marjon’s address was still on Rosie’s desk.

Among her things we found cameras and no fewer than fifty photo albums. The majority offered a picture of her new life in Sweden. She appeared to have prospered, done a lot, and laughed a lot. There was Rosie on the deck of a handsome cruise ship, behind a sledge being pulled by six huskies in Antarctica, in a submarine next to the captain (of course!), with the queen of the Netherlands in Stockholm, on countless picnics with friends or family. Rosie was often in the foreground, smiling, wearing a stylish summer dress or an elegant fur coat in the snow. There were also several photos of mountains, factories, rivers, ships, ice floes, bridges, buildings. These subjects must have excited her.

We then found an old album from Rosie’s youth: her father and mother, her friends, Wim, the dance school, Leo, Kees, and John. The photos extended from her youth to the middle of 1942, and they bore handwritten captions in Swedish. My brother and sister saw our grandparents for the first time. I had already seen some of the pictures when I first visited Rosie in Stockholm, but that was just a small portion of what we found. For the first time we saw what life was like after she moved out of her parents’ house. There were newspaper clippings about dancing, many of them featuring photos of a radiant Rosie, and her old passport, which referred to her as a dance teacher by profession. We also came across two films, which I watched later when I got home. They had no sound, but they showed Rosie dancing, teaching, chatting with students in her attic dance school in Den Bosch. In one scene she was talking to her mother, our grandmother. Another captured my father and mother dancing together, young lovers gliding over the dance floor. I had never seen them like that before. There was nothing from the images to suggest that the war was already two years old and that the situation was grim.

We found a folder full of poems and songs, all of them written by Rosie in Westerbork, Vught, Auschwitz, Birkenau, Gothenburg, and Stockholm. We also came across a small diary with a lock. It was like an autograph book: Rosie invited friends she met after the war to write something in it. The first was the man who liberated her, Folke Bernadotte. He wished her lucka till, much success.

Then we discovered the diary she had spoken of in one of her letters from Westerbork, in which she had begun to write again in 1945 after the first one was destroyed by British bombs. It was in a folder with a green cover. I glanced inside and saw a foreword, written by hand in neat, elegant letters. The rest was typed, page after page, chapter after chapter, each with Roman numerals. The last pages were written in pencil with many erasures and corrections. Apparently she would write by hand first, then type up her draft. It looked well cared for.

We found reports of witness interrogations made in 1946 by the Dutch State Police of the people who had betrayed her. The reports not only exposed the betrayal of her ex-husband Leo, they also detailed the activities of her lover Kees, and of the people both men mixed with.

A separate folder was dedicated to correspondence with the Dutch government and other official authorities. Most of the documents were requests for the return of money and property or for compensation. Year after year, letter after letter, frosty treatment, poor results. A kind letter from Queen Juliana’s secretary stood out amid the official letters of rejection. At the back I discovered a chart of notary invoices that listed all our murdered relatives and what was left of their estates. It wasn’t much. The family was gone, and so was their money and property.

Little by little the pieces of Aunt Rosie’s hidden existence came together. All this new information widened and sharpened the picture. It told the story of a passionate, intense, and adventurous woman who, despite adversity, remained positive and optimistic.

The last thing we found was behind a painting on the wall: Rosie’s last will and testament. In Swedish, it conveyed her wish to have her ashes scattered in the bay she had looked out over for so many years. I hadn’t forgotten her request, but I decided not to mention it to the official for fear that he would refuse to release the urn. Scattering ashes in the bay is prohibited. But Rosie’s life was full of rules and regulations, and much of the time she simply ignored them. We decided to do the same and respect her last wishes.

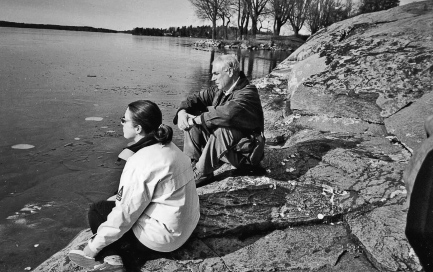

Paul and his daughter Myra after scattering Rosie’s ashes, 2000

That Sunday morning the four of us walked along the edge of Mälaren Bay. It was early March, and the sea was still frozen. A bird on the horizon flew low above the water. The sky was blue and cloudless. It was silent as a grave. Suddenly, in the distance, a tiny boat plowed its way through the thin ice. We waited until the silence returned, then I clambered onto a rock that jutted into the water and broke a hole in the ice. After a short ceremony, I poured Aunt Rosie’s ashes into the bay. Marjon had brought Dutch roses and she threw them onto the water. Roses for Rosie. Silence.