Notes

1. THE FIRST LIGHT OF EVENING

1. The case of Live Aid is drawn from Bob Geldof’s autobiography, Is That It? (London: Penguin, 1986), and from various newspaper accounts of the event. See also F. Westley, “Bob Geldof and Live Aid: The Affective Side of Global Social Innovation,” Human Relations 44, 10 (1991): 1011–1036.

2. World Bank, Controlling AIDS: Public Priorities in a Global Epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

3. For additional information on the background of the Brazil case please refer to James Begun, Brenda Zimmerman and Kevin Dooley, “Health Care Organizations as Complex Adaptive Systems,” S.M. Mick and M. Wyttenbach (eds), Advances in Health Care Organization Theory (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003): 253–288.

4. Adapted from S. Glouberman and B. Zimmerman, “Complicated and Complex Systems: What Would Successful Reform of Medicine Look Like,” in P.G. Forest, T. Mckintosh and G. Marchilden (eds), Health Care Services and the Process of Change (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004): 5.

5. Ibid., 26–53.

6. Ibid., 5.

7. This idea from E. Young, unpublished speech, “Policy Learning and Distributed Governance: Lessons from Canada and the U.K.,” June 5, 2003, Canadian High Commission/Demos Conference, London, UK.

8. For more information on Linda Lundström, please see www.lindalundstrom.com.

9. The case of Rusty Pritchard is drawn from personal interviews.

10. John Perkins, Let Justice Roll Down (Regal Books, 1976), and Robert Lupton, Theirs Is the Kingdom (New York: Harper and Row, 1989). See also www.ccda.org.

11. Jonathan Crane, “The Epidemic Theory of Ghettos and Neighborhood Effects on Dropping Out,” American Journal of Sociology 95, 5 (1989):1226–1254.

12. Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Viking, 1968), 4.

13. R. Fisher and W. Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving In (New York: Penguin, 1983).

2. GETTING TO MAYBE

1. The case of Reverend Jeffrey Brown was composed in part by Nada Farah, based on a presentation by Jeff Brown at McGill University in March 2003, and in part is drawn from Alexis Gendron and Kathleen Valley, 2000, Harvard Business School Case, “Reverend Jeffrey Brown: Cops, Kids and Ministers.”

2. Jenny Berrien describes how the police chose to ignore the issue of youth violence in order to avoid acknowledging that Boston, like New York, Chicago and other major U.S. cities, was becoming a pool of drug and gang crime. “The Boston Miracle: The Emergence of New Institutional Structures in the Absence of Rational Planning,” honours thesis, Harvard College, March 1997.

3. Alexis Gendron and Kathleen Valley highlighted in “Reverend Jeffrey Brown” that the mistrust between the black community and the white Irish police, or Irish Mob as the police was called then, was also due to the lack of common ground between the two groups.

4. Brown described the details of the Morning Star incident. Dan Kennedy, in his article “The Best: Local Heroes” for the Boston Phoenix, June 11, 1996, detailed the incident and provided us with the name of the victim as well as the exact date the attack occurred.

5. For more information on the TenPoint Coalition, see www.bostontenpoint.org.

6. Geldof, Is That It? 271.

7. Robert Frost, “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” in The Complete Poems of Robert Frost (New York: Holt Rine and Winston, 1967), 359.

8. The story of Edward Lorenz’s discovery is told in many books, including James Gleick, Chaos: Making of a New Science (New York: Viking), 1987.

9. Jonathan Patz et al., “Impact of Regional Climate Change on Human Health,” Nature, November 17, 2005, 1–8.

3. STAND STILL

1. We have drawn from two primary books for the story of the Grameen Bank and Muhammad Yunus: David Bornstein, The Price of a Dream: The Story of the Grameen Bank (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), and Muhammad Yunus, Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle against World Poverty (New York: Public Affairs, 1999). Further information on the Grameen Bank can be found at www.grameen-info.org/bank.

2. Yunus, Banker to the Poor, 34.

3. Ibid., 48.

4. Ibid., 63.

5. David Bornstein, How to Change the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

6. Yunus, Banker to the Poor, 35–36.

7. Parker Palmer, The Active Life (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1990), 55–56.

8. Ibid., 55–56.

9. The idea of resilience is drawn from the work of C.S. Holling and his colleagues at the Resilience Alliance. In 2002, they brought together many scholars to address the panarchy model in L.H. Gunderson and C.S. Holling (eds), Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington, D.C.: Island Press).

10. Adapted from diagram on the Resilience Alliance website. See http://www.resalliance.org/570.php.

11. Danny Miller, The Icarus Paradox: How Exceptional Companies Bring about Their Own Demise (New York: HarperCollins, 1992).

12. The story of PLAN is paraphrased and cited from the case, “Voice and Ground: Social Innovation at the Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN),” prepared and written for this project by Warren Nilsson, research assistant to the think-tank, under the direction of Frances Westley. Warren Nilsson is a doctoral candidate at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. Further information on PLAN is available at www.plan.ca.

13. T. Kuntz, “What Keeps Us Safe: The Care between Citizens” Abilities (Winter 2001): 40–41.

4. THE POWERFUL STRANGERS

1. W.B. Yeats, “Remorse for Intemperate Speech,” quoted in Geldof, Is That It?

2. Complexity theorists describe such distribution as “power law”—the lumpy, uneven distribution of connections that characterize self-organizing systems on the edge of chaos. The most cited case of this kind of “power law” distribution is the Internet. Sites on the Internet that are visited most often move up the hierarchy in search engines and so are visited yet more often. A pattern emerges of star sites, visited much more often than average, and a clear divide arises (as opposed to a continuous hierarchy) between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” Hence the notion of a power law: the pattern is not one of smooth increases, but of discontinuities of great magnitude, in mathematical language “raised to the power of x.”

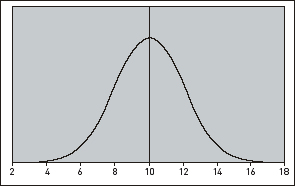

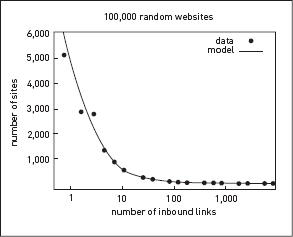

Simple comparisons of two types of distribution are shown in figures 1 and 2 below. In figure 1, we see a bell distribution, which is called a “normal” distribution. In this case, the average also represents a highly likely state. Most cases cluster around the average. The further one is away from the average, the fewer cases there are. This is the case for either tail, for either side of the average. Figure 1 could represent how many houses are on a block in a neighbourhood. Here we see a few blocks with very few homes, four or five. There are about the same number with many more than the average, fifteen or sixteen. But most cluster around the average and the tails disappear quite quickly. Most blocks have ten houses, give or take a house or two. The average becomes a very significant descriptor. To say the average block in this community has ten houses gives a pretty good description of the housing density in the neighbourhood. We see the same type of distribution in heights of people. The average height is a useful means to describe a population. Most cluster around the average and one would not imagine, other than in horror movies or fantasy books, a person who is ten times the average height or ten times smaller than the average. But in Figure 2, we see a power law distribution where there is no clustering around an average. To say the average website has x number of incoming links is quite meaningless when most sites have only one or fewer links and a small number of sites have ten thousand incoming links. Distribution of connectedness on the web is very lumpy, indeed.

Figure 1: A normal distribution or bell curve

Figure 2: Power law distribution of websites

Power law patterns are created not through the action of any individual but as a result of multiple micro-level choices. Some systems characterized by power laws, such as the uneven utilization of words (with some words used much more often than others), are subject to “tipping points,” sudden reconfigurations based on fads, epidemics, etc. We will consider this phenomenon further in the next chapter. In this chapter, it is important to recognize that other systems characterized by power laws are probably more resistant to tipping points. It would appear that once the distribution of the resources for creating and maintaining a particular social order take on a power law or “haves and have-nots” quality, that social system is resistant to change. “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer” is the maxim commonly used to capture this characteristic. The hubs, once formed, seek to maintain themselves.

3. Leonard Cohen and Sharon Robinson, “Everybody Knows,” from the album Cohen Live. Stranger Music Inc. (BMI), 1988.

4. The HIV/AIDS case was drawn from a detailed study of the dynamics of interaction of the different groups involved in changing the approach to HIV/AIDS treatment. For a fuller discussion see S. Maguire, N. Phillips, and C. Hardy, “When ‘Silence = Death,’ Keep Talking: Trust, Control and the Discursive Construction of Identity in the Canadian HIV/AIDS Treatment Domain,” Organization Studies, 22, 2 (2001): 287–312.

5. Ibid., 300.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., 309.

8. F. Westley, “Not on our Watch: The Biodiversity Crisis and Global Collaborative Response,” in D.L Cooperrider and J.E. Dutton (eds), Organizational Dimensions of Global Change (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 1999), 88–113.

9. The case of Ulysses Seal and CBSG is drawn from personal interviews and from earlier writings including F. Westley and H. Vredenburg, “Interorganizational Collaboration and the Preservation of Global Biodiversity,” Organization Science 8, 4 (1997), 381–403. For more information on CBSG and its activities see www.cbsg.org.

10. K. Alvarez, The Twilight of the Panther (Sarasota, FL: Myakka River, 1994.), 447.

11. The case of Mary Gordon and Roots of Empathy was drawn from personal interviews and Amy Eldon’s interview with Mary Gordon for the PBS series Global Tribe, at www.pds.org/kcet/globaltribe. For further information on Roots of Empathy, see www.rootsofempathy.org.

12. Russell Daye, Political Forgiveness: Lessons from South Africa (New York: Orbis Books, 2004).

13. We have drawn from various works of Cicely Saunders including “The Evolution of Palliative Care,” Patient Education and Counseling 41 (2000): 7; “A Personal Therapeutic Journey,” British Medical Journal 313, no. 7072 (1996), http://bmj.bmjjournals.com; and Cicely Saunders, Dorothy H. Summers and Neville Teller (eds), Hospice: The Living Idea (London: Edward Arnold, 1981).

14. Robert G. Twycross, “Palliative Care: An International Necessity,” Journal of Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 16, 1 (2002), 5-79.

15. The case of Dr. Balfour Mount is drawn from an article by Frances Westley, “Vision Worlds,” Advances in Strategic Management, 8 (1992): 271–306.

5. LET IT FIND YOU

1. Geldof, Is That It? 281.

2. M. Czikszentmihaly, Finding Flow (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

3. Ibid., 30–31.

4. Interview with Edwin Land. For fuller account, see F. Westley and H. Mintzberg, “Visionary Leadership and Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal 19, 2 (1989): 134–143.

5. E. Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (New York: Free Press, 1965), 134.

6. Steven Johnson, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software (New York: Scribner, 2001).

7. These examples of dagu were provided by C.Y. Gopinath from PATH in Nairobi. Used with his permission.

8. A. Downie, “Brazil: Showing Others the Way,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 25, 2001, www.aegis.org/news/sc/2001/sc010310.html.

9. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1970).

10. Glouberman, and Zimmerman, “Complicated and Complex Systems.”

11. Jane Jacobs is the author of many books including The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1951); Dark Age Ahead, (New York: Vintage Books, 2005); and Systems of Survival (New York: Vintage Books, 1994).

12. Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point (New York: Little Brown and Co., 2000).

13. Henry Mintzberg, “Crafting Strategy,” Harvard Business Review 65, 4 (1987): 66–76.

14. E. Helpman and Paul Krugman, Market Structure and Foreign Trade (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985.)

15. The case of Paul Born and OP2000 is drawn from personal interviews and from D. McNair and E. Leviten-Reid, “A Radical Notion,” Making Waves 13, 3 (2002): 19–29. For Paul Born’s current initiatives, go to www.tamarackcommunity.ca.

16. For a fuller discussion of improvisation see Karl Weick, “Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis,” Organization Science 9 (September/October 1998): 543–555. The simplistic understanding of improvisation (“making something out of nothing”) belies the discipline and experience on which improvisers depend, and it obscures the actual practices and processes that engage them. Improvisation depends, in fact, on thinkers having absorbed a broad base of knowledge, including myriad conventions that contribute to formulating ideas logically, cogently and expressively.

17. Weick coined the term “heedfulness” to address intense listening that happens in groups when they are being mindful of the emerging patterns at multiple levels.

18. P. Berliner, Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 401.

19. One source of information for sharing comes from evaluation. Standard practice in evaluation, as in research generally, is to carefully develop all data collection protocols and procedures prior to fieldwork. This is sensible in that it ensures that the appropriate and relevant data will be collected in a way that is valid and reliable. Sampling, instrumentation, interview and survey questions, statistical indicators analysis procedures are all specified in the design. The problem is that this assumes one can predetermine what is appropriate, relevant and useful. Evaluating emergent phenomena, like social innovation, requires emergent evaluation designs. This means snowball sampling (building the sample along the way as information accumulates and new sources of data are discovered), adapting inquiry questions and instrumentation as initial results come in, and using rapid appraisal techniques, quick analysis, ongoing feedback and open-ended fieldwork in search of the unanticipated. These are not standard evaluation operating procedures but they are essential if the evaluator is to be open to letting crucial information emerge and, in a very real sense, find the evaluator. Evaluation information can both reveal flow and be part of flow, the latter when the data seem to come pouring in and the evaluator is racing to keep up with what’s emerging. Instead of the usual drudgery and meaningless paperwork associated with most evaluations, real in the flow evaluative data collection and feedback contributes to the excitement of learning and the anticipation and realization of new understandings that inform the next steps in the innovation process.

6. COLD HEAVEN

1. See Terry J. Allen, “The General and the Genocide: General Roméo Dallaire,” Amnesty International NOW Magazine, Winter 2002, available at www.thirdworldtraveler.com; Roméo A. Dallaire and Brent Beardsley, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2004).

2. Tana Dineen, “The Solitary, Tortured Nobility of Roméo Dallaire,” Ottawa Citizen, July 13, 2000. Retrieved May 2, 2006, from http://tanadineen.com.

3. Roméo Dallaire, “Speaking Truth to Power,” keynote address and follow-up fireside chat at “Crossing Borders, Crossing Boundaries,” Joint International Evaluation Conference of the Canadian Evaluation Society and the American Evaluation Association, Toronto, November 5, 2005. See also Dallaire and Beardsley, Shake Hands with the Devil.

4. Born’s innovative community engagement institute: http://tamarackcommunity.ca.

5. From personal interview with Paul Born.

6. Westley, “Not on Our Watch,” 102.

7. Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t (New York: HarperBusiness, 2001).

8. Such step-by-step specification from inputs through activities to outputs and outcomes is called a logic model. Logic models have become a common requirement for funding proposals submitted to major philanthropic foundations. In some cases this specification is called a theory of change or program theory. All such conceptualizations require the pretense of prior knowledge about exactly how an innovation will unfold. In highly emergent, complex environments such prior specification is neither possible nor desirable because it constrains openness and adaptability. Developmental evaluation is an alternative that embraces emergence and complexity.

9. Dorothy Day founded the Catholic Worker movement. For more information on her life see Jim Forest, “A Biography of Dorothy Day,” on Paulist Father’s website, www.paulist.org/dorothyday/ddaybio.html.

10. Interview on Minnesota Public Radio, November 17, 2004: http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2004/11/17_olsond_development/.

11. Deanne Foster and Mary Keefe, “Hope Community: The Power of People and Place,” in McKnight Foundation, End of One Way (Minneapolis, MN: McKnight Foundation, 2004), 34.

12. Interview by Michael Patton.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Foster and Keefer, “Hope Community: The Power of People and Place.”

16. Evaluators tend to give highest prestige to “summative” evaluations, those focused on judging the overall merit, worth and significance of a program, and determining whether the program worked as specified in its logic model, including whether the targeted goals were attained. In contrast, “formative” evaluations are conducted to improve a program, identify strengths and weaknesses, and ready the program for the rigorous demands of summative evaluation. Hope’s questions differ from the usual type of formative evaluations because Hope’s leadership focused on an open-ended approach to data gathering, where the questions and concerns were emergent, and where trial and error was carefully mined for learning against a backdrop of changing goals as what the leadership understood was needed and possible changed within the context of their larger vision and values.

17. Foster and Keefe, “Hope Community: The Power of People and Place,” 40.

18. For more on the organization and its history see www.damianocenter.org.

19. See www.amizade.org/Countries/DC.htm.

20. A more in-depth discussion of developmental evaluation in relation to complexity science may be helpful to those involved in implementing such an approach. The nonlinear nature of emergent social innovation gives rise to inherent tensions in the struggle to figure out what it means to be successful. These tensions can be considered as paradoxes. Paradox was a regularly recurring theme in the stories of social innovation we heard. We found particularly challenging paradoxes appearing in the encounter with cold heaven, that is, in attempting to identify, understand and learn from what is and is not working, and the consequences of interpreting something as success or failure.

Chapter 3, “Stand Still,” highlighted the marriage of inquiry and action, that is, action as a form of inquiry and inquiry as a form of action. Traditional evaluation insists on separating evaluative inquiry from action by making the evaluation external to the intervention and making the evaluator independent of and distant from those engaged in bringing about change. Complexity-based, developmental evaluation joins inquiry and action in the challenge of being simultaneously engaged and reflective, open and evaluative, and fiercely committed by being fiercely skeptical.

Another evaluative tension surfaces in being simultaneously goal oriented and open to emergence. Inherent in the notion that something has succeeded or failed is the idea that something desired (usually called a goal or intended outcome) was or was not attained. But in complex, non-linear, emergent processes, direction can be fluid, ambiguous and ever evolving. Paradoxically, openness to what emerges becomes the goal, even though one is simultaneously moving forward toward an envisioned future. Acknowledging and embracing this tension opens the social innovator to evaluating short-term desired outcomes (how and where are we making progress?) while also rigorously watching out for unanticipated consequences, unpredicted (and unpredictable) side effects, spinoffs and ripples emanating from interventions (what is happening around and beyond our hoped-for results?). The narrow goal orientation of much traditional evaluation can result in missing such important unanticipated outcomes. To be sure, a major effort at social innovation is likely to have both short-term objectives along the way (here’s what we hope to accomplish in the next six months) and a long-term vision, but along the journey complexity theory alerts us to be mindful of the unexpected, and emergent. Moreover, the language used in traditional evaluation, which talks of “side effects” or “secondary effects,” “unexpected results” and “unanticipated consequences,” tends to be dismissive of outcomes that might, in fact, be crucial achievements or reveal opportunities for critical learning. While traditional evaluation judges mistakes and unattained objectives as failures, developmental evaluation treats them as learning opportunities and chances to make corrections or to take a new path.

As Chapter 4, “The Powerful Strangers,” highlighted, power relationships are transformed when social innovation processes are based on complexity insights. There are tensions here between maintaining and giving up control, between knowing where you are going and being open to where the process takes you, and between being part of the unfolding process even as you stand outside of and evaluate that unfolding process. Ongoing, intensifying interactions and deepening relationships replace formal and traditional forms of control (such as the determined implementation of an ordained plan or adherence to an approved evaluation design with specified samples and measures). Monitoring through interaction and relationship involves both a different kind of control (because it becomes relational and interdependent) and relinquishing control for the same reason. Evaluators have traditionally been admonished to remain external, independent and objective, but complexity-based developmental evaluation recognizes that data collection is a form of action and intervention, that the act of observation changes what is observed and that the observer can never really remain outside of and external to what he observes. The evaluator gives up the control that typically resides in rigid, preordained designs in order to experience and gain insight from observations (both anticipated in the design and emergent beyond the formal design) that come only from standing closer to and in relationship with the action and the primary actors. Moreover, even the roles shift, for the actors and innovators are simultaneously (and paradoxically) both the evaluated and the evaluators, and the developmental evaluation facilitator, by entering actively into the arena, even as an observer, becomes part of the action and therefore part of the intervention.

Tension resides in the paradox of, on the one hand, accepting constrained personal power and responsibility in the face of larger system dynamics and macro forces and yet, on the other hand, believing that individuals can make a difference and are responsible and acting accordingly. Evaluation, then, in a complexity framework, should encourage cross-scale and micro-macro reflections in order to facilitate learning about the effectiveness of discrete micro actions and the implications of those actions in relation to larger uncontrollable macro forces and trends. Developmental evaluators work with social innovators to look closely at and understand apparent “failure” at the personal level at different levels of analysis including in the context of larger macro forces, and provide an opportunity for “standing still” and learning, hopefully an antidote to cold heaven despair, and perhaps even a bridge to renewed commitment and action.

The tension in evaluation between learning and accountability is often palpable. Accountability is traditionally focused on compliance with prescribed and approved procedures and attaining intended results. Learning, in this framework, becomes learning about how best to attain the desired outcomes—and only that. This leaves little or no space to learn that the intended outcomes were inappropriate or less important than new, emergent possibilities. Failure as defined in traditional evaluation (as goals not attained) becomes reframed as feedback from a complexity perspective. This is captured in the complexity conclusion: it didn’t work—which means it worked. What didn’t work was our fallible effort at change. What did work was the “system” the world unfolded as it is wont to unfold. Knowing that allows us to approach and reframe seeming failure as an opportunity to learn, regroup and take another shot. The only real failure is the failure to learn. Accountability shifts from compliance to learning: not just any learning, but learning that bears the burden of demonstrating that it can, does and will inform future action.

We would add here that performance indicators, though all the rage in government, offer little in the way of real accountability. Crime rates, unemployment rates and standardized achievement tests in education offer important insights about trends, but those data require interpretation. That’s where things get tricky. In both the private and public sectors, we have seen the manipulation and corruption of indicators where the stakes are high: think of Enron manipulating its quarterly profit reports or the manipulation and distortion of supposedly objective “intelligence analysis” used to justify the invasion of Iraq. Preoccupation with measuring a few indicators creates a kind of tunnel vision that shuts out the complexity of reality. Things appear simpler and more controllable than they are. Interpreting indicators in a broader context means not just knowing whether the number has changed but delving into why it has changed, what the change means and what other changes are occurring at the sample time. That moves the interpretation from simple to complex.

Interpretations of performance indicators are greatly enhanced by incorporating other evaluation methods. Using mixed methods, multiple sources and diverse lenses to engage in deep reality testing will usually yield a complex picture of change. Quantitative data on trends and outcomes need to be contextualized and interpreted in the light of qualitative observations and purposefully sampled case studies. All data sources and informants come with errors and limitations, so multiple sources must be filtered and aggregated to build more holistic understandings of dynamic systems. Diverse interpretive lenses and theoretical frameworks guard against the disease of “the hardening of the categories,” where one forces all data through a narrow, predetermined way of making sense of complex systems.

21. Professional evaluators have an important role to play in supporting reflective practice and ongoing learning, and maintaining a sense of perspective—if they are willing and able to engage in developmental evaluation. But evaluators often hinder social innovation by imposing overly rigid designs and aiming at definitive judgments to satisfy narrow accountability demands. It is important to be sure that the nature of the evaluation matches the nature of the social innovation. We caution evaluators not to impose summative evaluation designs on developmental innovations. More broadly, evaluators and those who fund evaluation need to remain clear about different evaluation purposes and the importance of matching evaluation processes and designs to the nature of the intervention.

Where learning has a high priority, the evaluator can play a role in facilitating learning and helping those involved avoid premature and unbalanced summative judgments. Something as simple as changing the evaluative question from “Did it work?” to the more complex question “What worked for whom, in what ways and from what perspectives?” can deepen the possibility for learning and avoid an overly simplistic judgment of failure or success.

22. For a description of the tribunal, see Internews, “CTR Reports,” www.internews.org/activities/kTR_reports/ICTR_reports.htm.

7. WHEN HOPE AND HISTORY RHYME

1. Candy Lightner and N. Hathaway, Giving Sorrow Words (New York: Warner Books, 1990).

2. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Report, 1996. See http://www.alcoholalert.com/drunk-driving-statistics-2001.html.

3. Cited on the MADD website, http//www.madd.org/aboutus/1179.

4. John Dresty, “Neo-Prohibition,” The Chronicle, May 12, 2005.

5. In the U.S. press, .10 BAC is widely understood to mean .10 blood alcohol content. Equivalencies depend on body weight, gender, food intake, length of time drinking and type of drink. To compute equivalencies for your own weight and consumption, see Minnesota State Patrol Trooper’s Association, “BAC Calculator,” www.mspta.com/BAC%20Calc.htm. For further detail see the following websites: Intoximeters, Inc., “Alcohol and the Human Body,” www.intox.com/physiology.asp, and University of Prince Edward Island, “Blood Alcohol Levels,” www.upei.ca/~stuserv/alcohol/bac1.htm.

6. David J. Hanson, “Mothers Against Drunk Driving: A Crash Course in MADD,” www.alcoholfacts.org/CrashCourseOnMADD.html.

7. David J. Hanson, “Zero Tolerance,” Alcohol Problems and Solutions website, www2.potsdam.edu/hansondj/ZeroTolerance.html.

8. Hanson, “Mothers,” n10.

9. Columbia Accident Investigation Board 4, Final Report, 4 vols. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2003). See also http://caib.nasa.gov.

10. MSNBC, “Shuttle Report Blames NASA Culture: Investigative Panel Sees ‘Systematic Flaws’ That Could Set the Scene for Another Accident,” August 26, 2003. www.msnbc.msn.com.

11. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), based in Boston, is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving the quality of health care systems through education, research and demonstration projects, and through fostering collaboration among health care organizations and their leaders. IHI projects extend throughout the United States and Canada, numerous European countries, the Middle East, and elsewhere. www.ihi.org.

12. Plenary address at the 14th Annual National Forum in Quality Improvement in Health Care, Orlando, FL, December 10, 2002.

13. Stuart Kauffman, At Home in the Universe: The Search for the Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1996).

14. Roger Lewin, Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

15. Holling and Gunderson, Panarchy.

16. Adapted from ibid., 75.

17. To learn about the work of Philia, see www.philia.ca.

18. E. Land, “People Should Want More from Life,” Forbes, 1975, 48–50.

19. Adapted from Holling and Gunderson, Panarchy.

20. www.calmeadow.com.

21. In more technical terms, we suggest analyzing macro-micro alignments and cross-scale interactions in changing fitness landscapes.

Practice can be enhanced by forming a community of reflective practitioners devoted to macro–micro pattern recognition and reality-testing skills. Developmental evaluators can also play a role in this reflective process. Those deeply enmeshed in change can benefit from the external, more detached perspective that trained evaluators bring. We’ve emphasized this point over and over throughout this book. One of our goals has been to help social innovators come to see evaluation and evaluators as resources for and enablers of change rather than a hindrance. But that, we’ve also argued consistently, requires a different kind of evaluator, one attuned to complexity insights. So we would suggest that evaluators add to their repertoire the capacity to identify and track hope-and-history rhymes. Detecting macro-micro alignment offers a framework for bringing systems understandings into evaluation, especially making understanding of context and system dynamics central to interpreting findings.

Embedded within every evaluation is a way of thinking about the world. Entrenched in developmental evaluation are sensitivities to systems dynamics, continuous change and ongoing learning. Judging macro-micro alignment is fundamentally an evaluation problem. Interpreting a fitness landscape is fundamentally an evaluation problem. Evaluators familiar with and comfortable with these more open and emergent developmental evaluation approaches will be a better match for social innovators and the challenges they face.

This suggests that the primary challenge is to match the evaluation approach to the nature of the effort being evaluated. Where social innovators are monitoring and attending to macro-micro alignments, evaluators schooled only in traditional linear modelling and narrow goals-focused measurement will actually become barriers to rather than enhancers of innovation. To be useful and assure appropriate methods, evaluators need to adapt to the nature of the social innovation rather than imposing traditional evaluation on non-traditional innovations—beginning with being able to recognize the difference.

8. THE DOOR OPENS

1. T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding,” from Four Quartets, in The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1952), 145.

2. Adapted from Peter B. Vaill, Learning as a Way of Being; Strategies for Survival in a World of Permanent White Water (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996).

3. You can hear a sound clip from this interview at www.cbsg.org/ulie/soundbite.html.

4. W.B. Yeats, “Dialogue of Self and Soul,” in The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume 1: The Poems (New York: Scribner), 240.