1. English Protestant identity in the seventeenth century was powerfully shaped by a fear of Catholic conspiracy that was in part rooted in history. This print dates from 1621 and depicts England's double providential deliverance from the Spanish armada of 1588 and the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. An embellished version of this print was published in 1689 to celebrate England's most recent ‘deliverance’.

2. A woodcut from 1685 depicting royalist victory over the Monmouth rebels at Sedgemoor.

3. The infamous Popish Plot informer Titus Oates, convicted on two counts of perjury at the beginning of James II's reign, was sentenced to two public whippings, perpetual imprisonment, and annual stints in the pillory. The Revolution brought him a pardon and a pension. The clause in the Declaration of Rights condemning excessive and unusual punishments alluded to the treatment meted out to Oates.

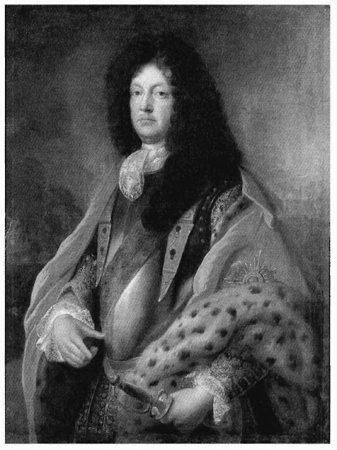

4. James's right-hand man in Ireland, Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnell. A long-standing friend of the king, he was an embittered enemy of the Restoration land settlement and the champion of the Catholic interest in Ireland.

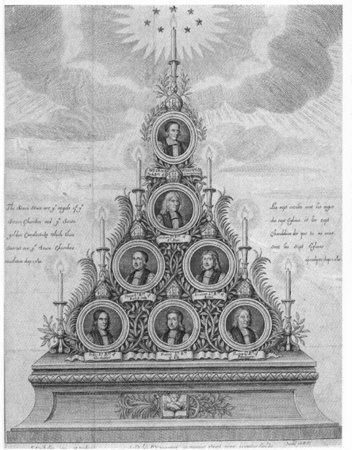

5. The seven bishops who petitioned against James's second Declaration of Indulgence of 1688. Tried for publishing seditious libel and found not guilty by a London jury, their opposition marked the beginning of the end for James II's regime.

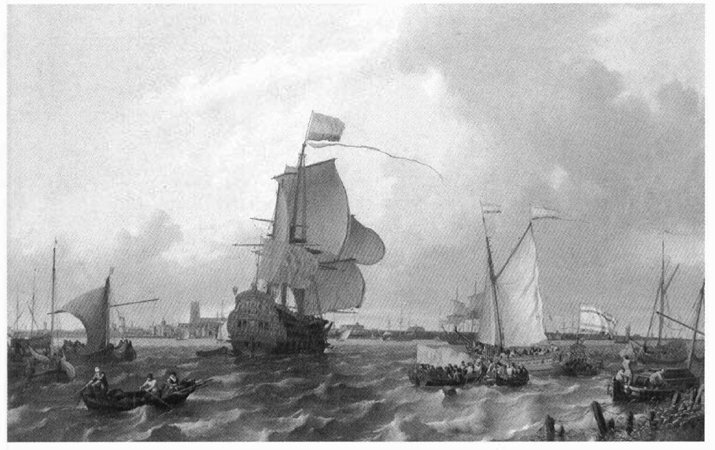

6. A Dutch painting depicting the embarkation of the Dutch fleet in the autumn of 1688. A ‘Protestant wind’ was to blow the fleet down the Channel towards Torbay.

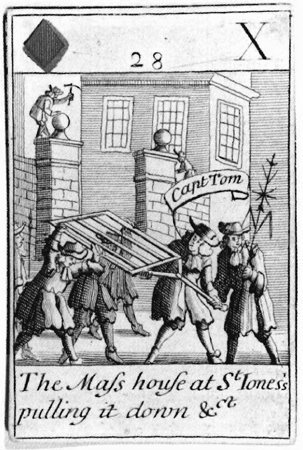

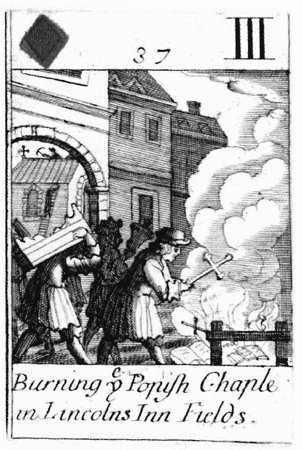

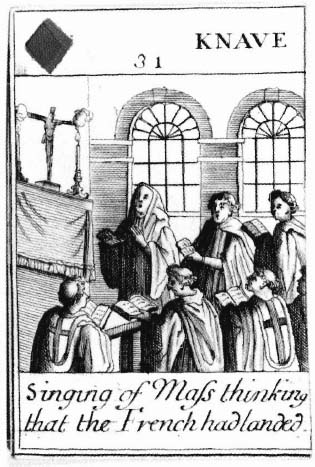

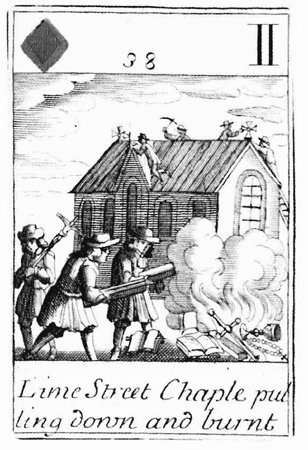

7. Illustrated playing cards from a pack produced to commemorate the Revolution of 1688–9. The II, III and X of diamonds depict the attacks on Catholic chapels in London in late 1688. The knave of diamonds shows an entirely fictional scene of Catholic clergy singing the mass in the mistaken belief that the French had landed to support James's tottering regime.

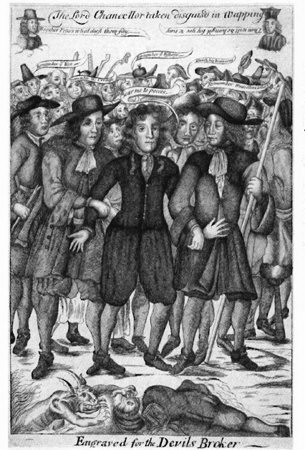

8. A contemporary engraving depicting the arrest of George Jeffreys, James's Lord Chancellor and the judge who had presided over the ‘Bloody Assizes’, at Wapping on 12 December 1688.

9. An illustrated ballad celebrating the return of James II to the capital on 16 December 1688, following his first abortive flight. Even at this late stage, some Protestants hoped that redressing their grievances might not necessitate the overthrow of their king.

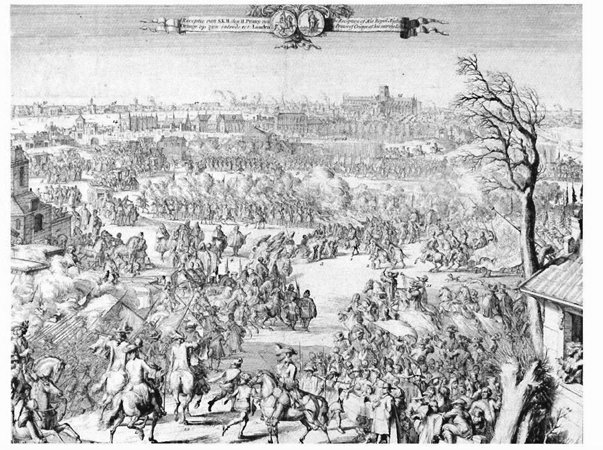

10. William of Orange was to make his own triumphal entry into London two days later, on 18 December. By this time James had once again been forced to leave the capital.

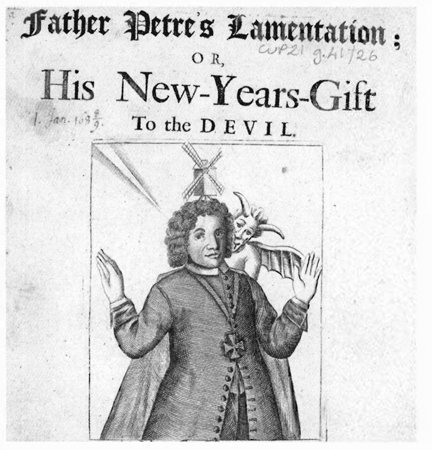

11. An illustrated broadside of 1689 rejoicing at the downfall of the Jesuit priest and privy counsellor Father Edward Petre. Such was Petre's influence with the King that he was considered by many to be ‘the first minister of state’ in 1687–8.

12. An allegorical design depicting England's deliverance from ‘French tirany and Popish oppression’ by William of Orange. Oranges falling from the tree in the centre knock down Jeffreys (to the right) and topple the crown from James II's head (to the left). The Queen flees with her infant son, while Louis XIV of France is shown murdering his own (Protestant) subjects. Note the watching eye of Providence, reminiscent of the print in Plate 1.

13. The front page of a pamphlet of 1689 celebrating the coronation of William and Mary on 11 April 1689.

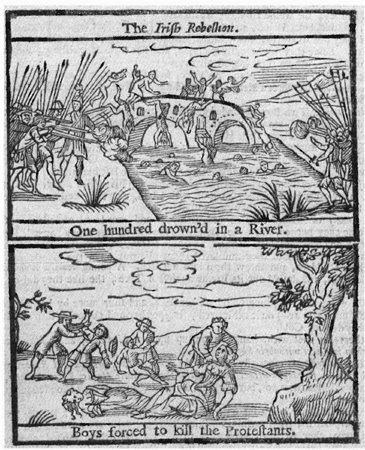

14. Illustrations from a Protestant propaganda tract of 1689 recalling alleged brutalities committed by Irish Catholics against Protestants during the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

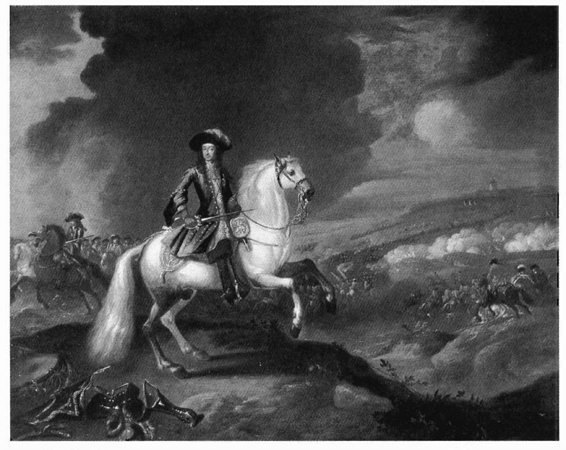

15. Dutch painting depicting William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690. The image of William on a white horse has, of course, become iconic in Northern Ireland, but in all likelihood William rode a brown horse: a white one would have made him too visible a target for the enemy.