“We hope to make this home one of fundamental beauty, and of functional patterns to supply our needs, both material and intangible.”

After completing his last concrete block house in the 1920s, Wright never used this method again on any of his houses in California. Instead, between 1939 and 1959, he designed four very different homes in Southern California that are as varied as the unique landscapes they occupy. These houses range from a magnificent retreat perched atop the mountains above Malibu to a spacious and light-filled family home on the edge of the Mojave Desert.

The Santa Monica Mountains rise steeply from the Pacific Coast Highway above Malibu, reaching elevations of over 2,200 feet at their highest peaks. Their rugged, craggy slopes have, as of yet, remained unspoiled, with only a handful of modern McMansions sprinkled amidst the few older ranches and historic homes that were built before the 1950s. Amongst these older homes is the Arch Oboler Gatehouse and Retreat, a group of buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1940 and 1941, with various additions and alterations made between 1944 and 1955. The setting of this compound is one of the most spectacular of any of Wright’s residences. The site is a 107-acre tract in an unincorporated section of Los Angeles County, at 32436 West Mulholland Highway. The land is spread out across a range of rocky peaks and crags, with valleys and level areas in between. The elevation of the site varies from about 2,000 feet to over 2,200 feet above sea level. The view from every part of this tract is magnificent, particularly at sunset, with the slopes of the mountains cascading down towards the Pacific Ocean in the distance, where the bright California sun often fills the sky with reds, pinks, and purples on a clear day.

Arch Oboler was a Hollywood producer, director, and screenwriter, who also wrote scripts for radio, including the popular 1930s program Lights Out. He knew Frank Lloyd Wright, having been hired to provide film projectors for Wright’s private movie theater at Taliesin West. About 1940, he decided he wanted to build a retreat and residence in the Santa Monica Mountains, one that would include post-production facilities and a writing studio. Lloyd Wright found the perfect site, and after Oboler purchased it, he commissioned the elder Wright to design a gatehouse, residence, retreat/guesthouse, stables, office, and children’s playrooms. Over the next four years, most of these facilities took shape, but the main house was never built. The gatehouse was completed in 1940, the retreat in 1941, and the additions to the gatehouse were built between 1944 and about 1955. Oboler’s mercurial financial fortunes, which rose and fell with his various film ventures, kept him from being able to afford the cost of the primary residence Wright had designed for him. The fittingly romantic name Oboler gave to this compound was Eagle Feather, and he named the studio after his wife, calling it Eleanor’s Retreat.[1]

Arch Oboler Compound, Malibu, California (1940–55), guesthouse (Eleanor’s Retreat)

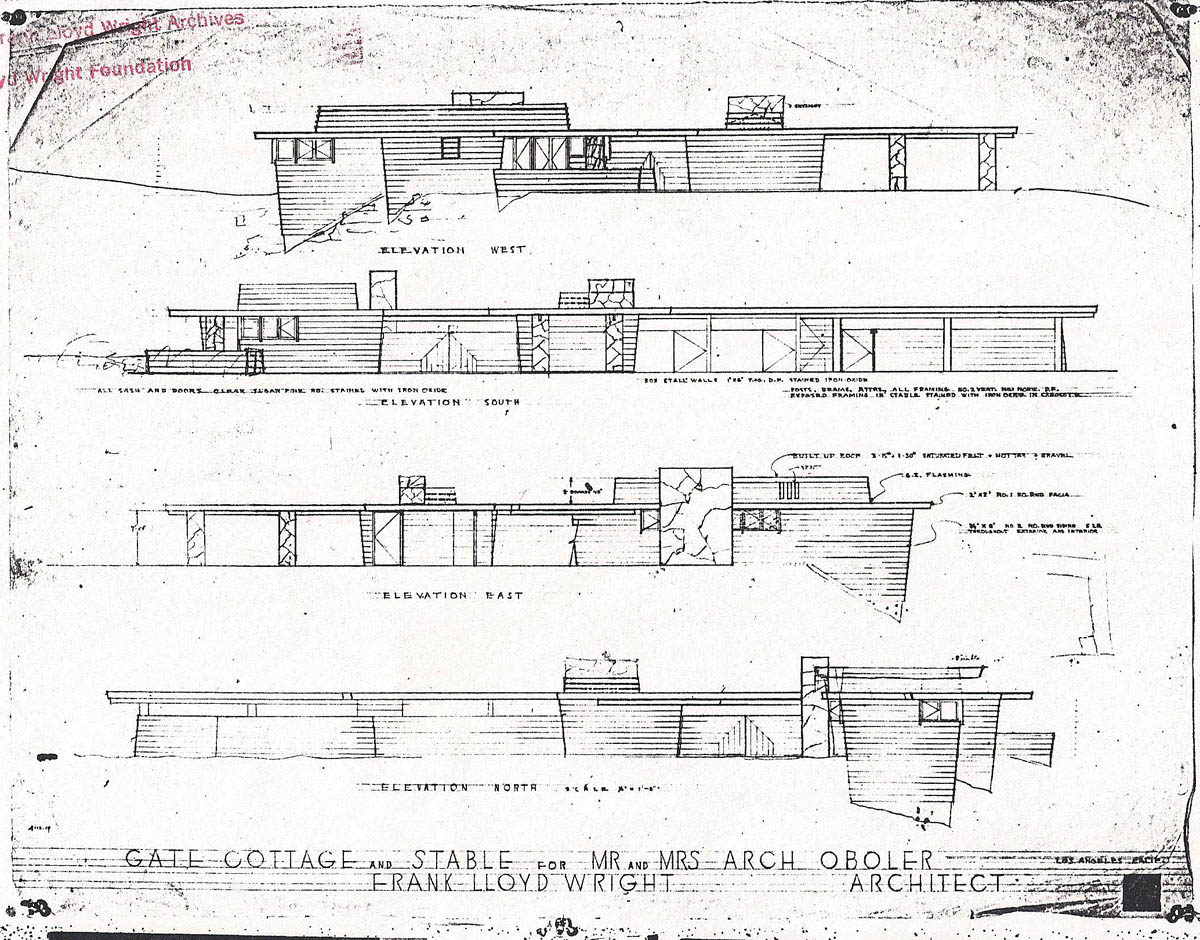

Oboler Compound, elevations of gatehouse. Copyright © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona.

The approach to the Oboler Compound is down a long, level driveway lined with walls made from fieldstone (or as Wright called it, rubblestone) in a variety of colors and textures taken from the site. This was the same material Wright used on most of the exterior walls throughout the rest of the compound. At the end of this driveway is a wide parking pad on the left, and the gatehouse is on the right. The gatehouse is actually one wing of a modified T-shaped group of structures that are under one roof. The gatehouse itself runs east–west, and its long northern wall has a row of stone pillars that protrude about two feet above the roofline, which creates the impression of an ancient Middle Eastern fortress or the battlements of a Medieval castle on a mountaintop.

The various structures at Eagle Feather display organic design features and a use of natural materials similar to those Wright had used for his own compound at Taliesin West in the Arizona desert. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Wright developed a highly personal genre called “desert aesthetic,” for architecture in arid climates, such as Arizona and Southern California. For masonry walls, he used local stone set into concrete that made them appear to have grown right out of the desert terrain. He also used wood siding on upper walls and low-angled or flat rooflines with wide overhanging eaves that made the buildings seem to nestle comfortably into the landscape. This system was used on the Rose Pauson House in Phoenix, Arizona, designed in 1939, as well as later homes in other parts of the West, such as the Berger House in San Anselmo, California, designed in 1950 (see Chapter 6). The Oboler Compound displays all these characteristics, especially when viewed from above, where it seems to be an extension of the natural landscape. Wright’s use of rubblestone pillars, interspersed with sections of picture glass windows and doors, creates a strong rhythmic quality, as does the inward tapering of the upper walls, and sheathing them in cedar clapboards (redwood was used originally, but replaced after it cracked in the dry climate).

The gatehouse wing contains the main living quarters, with a small living room and adjacent open kitchen to the left. This space has a warm, intimate feel, with a fireplace faced with rubblestone on the east wall, a cedar plank ceiling that tiers upward in the middle, and recessed lighting in the kitchen lined with cutout geometric patterns in wood. To the left of the kitchen is a bedroom and full bath. From the living room there is a superb view of the Pacific Ocean on clear days. The current owners describe this comfortable living space as “a small work of art—a gem.”[2]

Oboler Compound, looking north with gatehouse in distance.

Oboler Compound, south façade

Oboler Compound, looking west.

The children’s wing originally had an open staircase (later enclosed) that led to a children’s theater and a playroom downstairs. This wing has two levels, with the first level partially set into the gentle upslope hillside on which it sits. A rubblestone fireplace is set into the west wall on both levels, and steel-framed glass doors on the south end open out onto a terrace on the ground level. Upstairs, steel-framed banded picture windows across the upper wall provide a lovely view of a man-made pond below, which was part of the original landscape design done by Lloyd Wright. The ceilings in this wing are similar to those in the gatehouse, with coffered cedar planks, and the same geometric cutout patterns on recessed lighting set into them. There are two bedrooms and two baths on the upper level of this wing, and the theater and playroom are now being used as a family entertainment and media room. The original stable wing, running east–west off the carport, has been converted into a workroom with a kitchen and office, and also includes a laundry room, bedroom, bath, and sitting area.

The most impressive structure in the Oboler Compound is Eleanor’s Retreat. This is a small, separate structure that crowns the top of a craggy outcrop of rock near the southeast corner of the property. Wright designed it to be a self-contained unit for use as a guesthouse, or as a workspace or retreat for Eleanor. The main space is a light-filled open room with panoramic views of the Santa Monica Mountains from picture windows on the east, south, and west sides. A large open-hearth fireplace made of rubblestone and concrete dominates the north side of this room, with a full bath behind it. The floors are made of rubblestone, and two narrow windows on the west wall flank the fireplace, with a built-in desk below one of them and built-in shelving in the corners and along the walls. The roof is flat, with wide, overhanging eaves that jut far out over the west end. The outer walls are sheathed in cedar planks, with rubblestone for the lower walls. Stone was also used to construct the staircase and the retaining wall leading up to the doorway on the north side and the terrace running along the north and east sides.

Oboler Compound, interior living room

Oboler Compound, colonnade with desert masonry.

Oboler Compound, children’s wing looking south.

Oboler Compound, view through breezeway looking west.

Wright’s apprentice John Lautner oversaw the construction of the Oboler Compound. Wright came to the site in 1941, after Eleanor’s Retreat was completed. He was unhappy with the way Lautner had situated the staircase, so he had some of his “boys” from Taliesin West rebuild the stairs and retaining wall to run north–south in a straight line along the hillside.[3]

Arch and Eleanor Oboler lived in the compound for several years, during which Arch worked on several small-budget Hollywood films. These included a 1951 science fiction movie, Five, which was shot at and around the compound, about a group of post–nuclear war survivors. He also worked on the film Bwana Devil, the first-ever feature-length 3-D movie in color. Arch died in 1987, and Eleanor remained on the property for a few more years.[4] The compound was put on the market after her death, and it nearly met a sad fate when a developer bid on it, with plans to divide the property into 15 lots for luxury homes. His offer was accepted, but was withdrawn due to the housing crisis of the early 1990s.[5]

In 1996, Dorothy and John Knight bought the Oboler Compound. Since then, they have been engaged in a major restoration of the property, including repairing the damage from years of deferred maintenance. They have also done lots of landscaping work on the site, such as removing a pool that Arch Oboler had installed near the gatehouse, and putting in the large pond below Eleanor’s Retreat. They plan to bring this marvelous piece of California’s architectural heritage back to its full aesthetic beauty.

Oboler Compound, guesthouse looking south

Oboler Compound, blueprint of guesthouse floor plan. Copyright © The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona.

Oboler Compound, guesthouse bedroom looking east

Oboler Compound, detail of guesthouse fireplace

At the top of a wide, upslope lot in the tony Los Angeles suburb of Brentwood, two miles west of Beverly Hills, sits a home that is dramatically different from all of its neighbors. The George D. Sturges House, designed and built in 1939, is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most futuristic-looking West Coast residences. This one-story house appears to be hovering over its hillside lot: the entire east end of the house is cantilevered out over the site, thus presenting the most prominent profile of any home in this neighborhood. At the time it was built, this was a radical design for a house, even for avant-garde Southern California. Beginning in the late 1950s, streamlined homes jutting out over upslope sites began to be a common feature in hillside communities all over California. But in 1939, there were very few such houses anywhere on the West Coast.

The use of sweeping cantilevered masses projecting out over the landscape had first been employed by Wright on Fallingwater, the home he had designed in 1936 for Edgar Kaufmann in Pennsylvania. Though the sites are very different, the Sturges House, at 449 N. Skyewiay Road, has the same extended horizontal lines and dramatic profile that Fallingwater does. This type of design was Wright’s response to America’s fascination with speed and motion in the 1930s. Indeed, the Sturges House, with its wide projecting deck springing forward from a brick and concrete base, almost appears to be in motion. Wright’s use of kiln-dried redwood clapboarding along the exterior walls adds to the horizontal emphasis, and accentuates this effect. The square base and the rectangular massing of the brick-faced upper façade create a Cubist-like rhythm that counterbalances the cantilevered deck. Wright hired John Lautner to be the supervising architect for the construction of this innovative residence.

Sturges House, Brentwood, California (1939), view from north.

The Sturges House is one of Wright’s smallest homes in California, with only 900 square feet of interior living space. The interior space is supplemented quite effectively by Wright’s use of the balcony along the entire east side so that all the living areas are adjacent to it. The deck is 58 1/2 feet long, and 6 1/2 feet deep, thus providing another 380 square feet of usable space during all the warm days and nights that are so common in Southern California.[6] The deck wraps around the southeast corner of the house, providing a side terrace. The living room and two bedrooms have floor-to-ceiling windows that line the deck, and a plate glass door in the living room opens out onto the deck. A wide redwood trellis over the deck provides some shade on hot days, while square openings admit the morning sunlight into the interior. A bathroom, workspace, and utility area are located behind the bedrooms on the north side of the house off a long, gallery-style hallway. A narrow set of exterior stairs on the north side of the house leads from the side terrace to a spacious roof deck, with panoramic views in three directions, including a view of the Pacific Ocean about three miles to the west.

The roof of the Sturges House is flat, and Wright also used overhanging trellises on the west side of the house, where the recessed front door is set into the far south corner. This is a Dutch-style double door, and Wright placed it beneath a solid redwood overhang to shelter it from the elements. A long driveway leads up to this entrance, with a four-car carport running west from it—an unusually large parking space for the 1930s. The front door opens directly into the living room. This is an open rectangular room, with redwood paneling on the north and south walls, built-in wooden seating along the south wall, and a small fireplace on the west wall. The original Wright-designed redwood chairs are still here, and the floors are made out of linoleum in eight-inch-square sections in Wright’s favorite Cherokee red color.

The current owner of the Sturges House, former actor Jack Larson, bought the home in 1967. At that time, the house needed major work, including stripping paint off the exterior redwood, removing black paint from the interior walls, and replacing the leaking tar-and-gravel roof with a new water-resistant high-tech one.[7] At this writing, the house retains all of its original architectural features, and is a rare example of an intact Early Modern California house from the 1930s. It was designated a Historic-Cultural Monument by the City of Los Angeles in 1993.

Sturges House, view of north façade with carport

Sturges House, west façade view of entrance.

In the 1998 Hollywood film Permanent Midnight, starring Ben Stiller and Elizabeth Hurley, Hurley’s character lives in an elegant modern house in the suburban hills above the Los Angeles Basin, with stunning views of the city lights far below. It was the Wilbur C. Pearce House, in the tiny, affluent hillside town of Bradbury. Like a number of other Frank Lloyd Wright houses that were used in feature films, only the exterior scenes were filmed at the actual site, while a set was built for the interior scenes. This was done mostly because the interior of the Pearce House at that time was not well kept, with green paint covering all the original beige-colored concrete block walls, and deteriorating woodwork on the ceilings. A tenant occupied the home for several years, making changes to the décor and allowing deferred maintenance to take its toll. At this writing, however, the Pearce House has been owned for several years by Konrad Pearce, the grandson of the original owner, who has been working meticulously to restore the residence to its historical appearance. It now looks almost the way it did when it was finished in 1955.[8] The house is at 5 Bradbury Hills Road.

Wilbur C. Pearce was a marketing executive with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, and his wife, Elizabeth, was an abstract artist and president of the Women’s Art League in Akron while they lived in Ohio. The Pearces met Frank Lloyd Wright when Elizabeth invited him to give a lecture to Akron city officials about a proposed art museum. They became friends, and Wright later agreed to design a home for them once they had relocated to California.[9] In 1950, they bought a two-acre lot in the eastern foothills of unincorporated Los Angeles County, with views of the Los Angeles Basin and its city lights to the south, and the undeveloped San Gabriel Mountains and Angeles National Forest to the north. Wright drew up a full set of plans in 1950 for a single-story, two-plus-bedroom, two-bath, 1,900-square-foot house. Construction did not begin until 1954, and the Pearces moved into the home in 1955. William Wesley (“Wes”) Peters, one of Wright’s most trusted Taliesin associates, was the supervising architect. Wright’s original bid called for a budget of $15,000, but like so many of his other residential designs, the final cost was much more—in fact, it came to double that original figure.[10]

The Pearce House is a variation of Wright’s Usonian-style homes. In essence, this was Wright’s attempt to create a system of supposedly affordable, detached housing for middle-class families. These homes were all designed on a variant of a grid pattern, usually using square modules for the floor plans, and incorporating a number of signature features such as carports and concrete slab floors. The Pearce House is a bit different than most Usonian houses; here, Wright used a pattern of segmented circles for the floor plan and the exterior of the home. He had used this design module on a handful of earlier homes, such as the second Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House in 1944 in Middleton, Wisconsin, and the Kenneth and Phyllis Laurent House in 1949 in Rockford, Illinois.

Pearce House, Bradbury, California (1950–55), view of east façade

Pearce House, brown bear cub swimming in pool on east terrace. Photograph by Konrad Pearce

Pearce House, east façade looking south.

The materials Wright used on the Pearce House were concrete block for the walls, plate glass for the doors and windows, Douglas fir for the ceilings, and Honduran mahogany overlay on the window framing. The floors are made of concrete slabs, in three-foot-square patterns, stained Cherokee red. By far the most distinctive feature of the house is Wright’s use of a sweeping concave curve along the fascia on the south side. The fascia on the north side has a slight convex curve to it. All the fascias are several inches wide, creating a strong visual line at the end of the wide overhanging eaves that extend around the entire perimeter of this flat-roofed home. These eaves partially shade two terraces. The north terrace, off the living room, is in the shape of a pointed arch. The south terrace runs nearly the entire length of the house, following the curve of the fascia. There is a small pool set into the middle of this terrace, which Wright called the promenade. Konrad Pearce told me he has seen a family of black bears, a mother and her three cubs who often come down from the Angeles National Forest at dusk, playing in this pool (undoubtedly not the use Wright originally intended for it). At the east end of the house is a two-car carport beneath extended overhangs, and an adjacent workshop and half bath. (The workshop was designed to be used as Elizabeth’s painting studio, but it was too dark, so she used one of the bedrooms instead.) Konrad recalls that his grandparents told him the original tar-and-gravel roof did not leak for the first 10 years they lived there.[11]

The main entrance to the house is on the northeast end. The plate glass front door opens directly into the living room, which is a wide, open space that doubles as the dining room. Wright placed a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows on both the south and north sides of this room. A glass door opens from the southeast corner of the room out onto the curved terrace. Another glass door opens out onto the north terrace. Elizabeth asked Wright to alter his original plans for the windows on the north side to allow for a full view of the mountains. So Wright raised the height of the ceiling on this side so that the overhanging eaves would not cut off the view.[12] The ceiling in most of the living room is seven feet ten inches tall, with wood paneling between open beams. At the north end, the ceiling is two feet higher, with a plain glass clerestory running east–west around the edge of this raised section. A fireplace faced with concrete block is set into the east wall, and there are built-in bookshelves lining the northeast corner of the room. There is also a low built-in seat that runs along the wall between the fireplace and the northeast corner.

At the west end of the living room is a wood-sided service core that rises from the floor to the ceiling, with cabinets set into it and built-in shelves lining the north side. Behind this is a small kitchen, or as Wright called it, a workspace, with mahogany overlay cabinets and countertops. To the left of the service core is a long gallery that runs most of the length of the south side of the house. There is built-in shelving along the inner wall of the gallery, and the outer wall of floor-to-ceiling windows creates a pleasing indoor-outdoor effect, bathing the interior with natural light. The gallery connects the two bedrooms: a small bedroom in the middle of the house, and the master bedroom suite at the far west end. The master bedroom has floor-to-ceiling picture windows on the south wall, and narrow-slit wood-frame windows on the north wall. There is a small, adjacent full bath, and there are built-in storage cabinets along the north wall, as there also are on the north wall of the smaller bedroom.

The engineering of the Pearce House was supervised by Wes Peters, while the overall supervising architect was another of Wright’s most trusted associates from Taliesin, Aaron Green. Green reoriented Wright’s original placement of the house to avoid the steepest part of its hillside lot, and allow for more space for the workshop/studio wing off the east end.[13] Wilbur and Elizabeth occupied the house until they died, after which their son Llewellyn moved into it in 1985. Then Konrad Pearce obtained title to the property in 2002, and he has been spending much of his spare time since then restoring his grandfather’s elegant house to its original condition.

Pearce House, view of gallery looking south

Pearce House, view of living room/dining room looking north

Pearce House, view of living room with fireplace with green paint on concrete blocks. Photograph © 1988 Scot Zimmerman.

Pearce House, master bedroom looking south

Pearce House, north façade with carport.

At the edge of the Mojave Desert, near the eastern fringes of the boomtown of Bakersfield, sits the last house Frank Lloyd Wright designed on the West Coast, two months before he died in April 1959. The George Ablin House, at 4260 Country Club Drive, is one of the most spacious and gracious of Wright’s several 1950s homes in California. The house sits on a one-and-a half-acre lot, within the grounds of the Bakersfield Country Club. This single-story residence has 3,600 square feet of living space, with five bedrooms, four baths, a living room with a dining area, a kitchen, a study, and a swimming pool in the backyard. The larger-than-usual living space in the Ablin House was the result of a very active correspondence between Wright’s Taliesin staff and Dr. Ablin’s wife, Mildred, over the last year of Wright’s life. George Ablin was one of the most successful neurosurgeons in Bakersfield, which had a population of about 50,000 in the late 1950s.[14]

“Millie” Ablin first wrote to Wright in the summer of 1958, asking him to design a new home for George and herself and their large family. In a letter dated June 10, 1958, she stated:

We were wondering if it is possible for you and practical for us to have you design a home for us and our young family of six, and probably seven children (see enclosed picture—youngest is 8 and 1/2 years). We have a steep hillside lot (100 x 340) with an excellent view overlooking the community itself and the surrounding country, at the edge of the Mojave Desert, with mountains always prominently visible. We hope to make this home one of fundamental beauty, and of functional patterns to supply our needs, both material and intangible.[15]

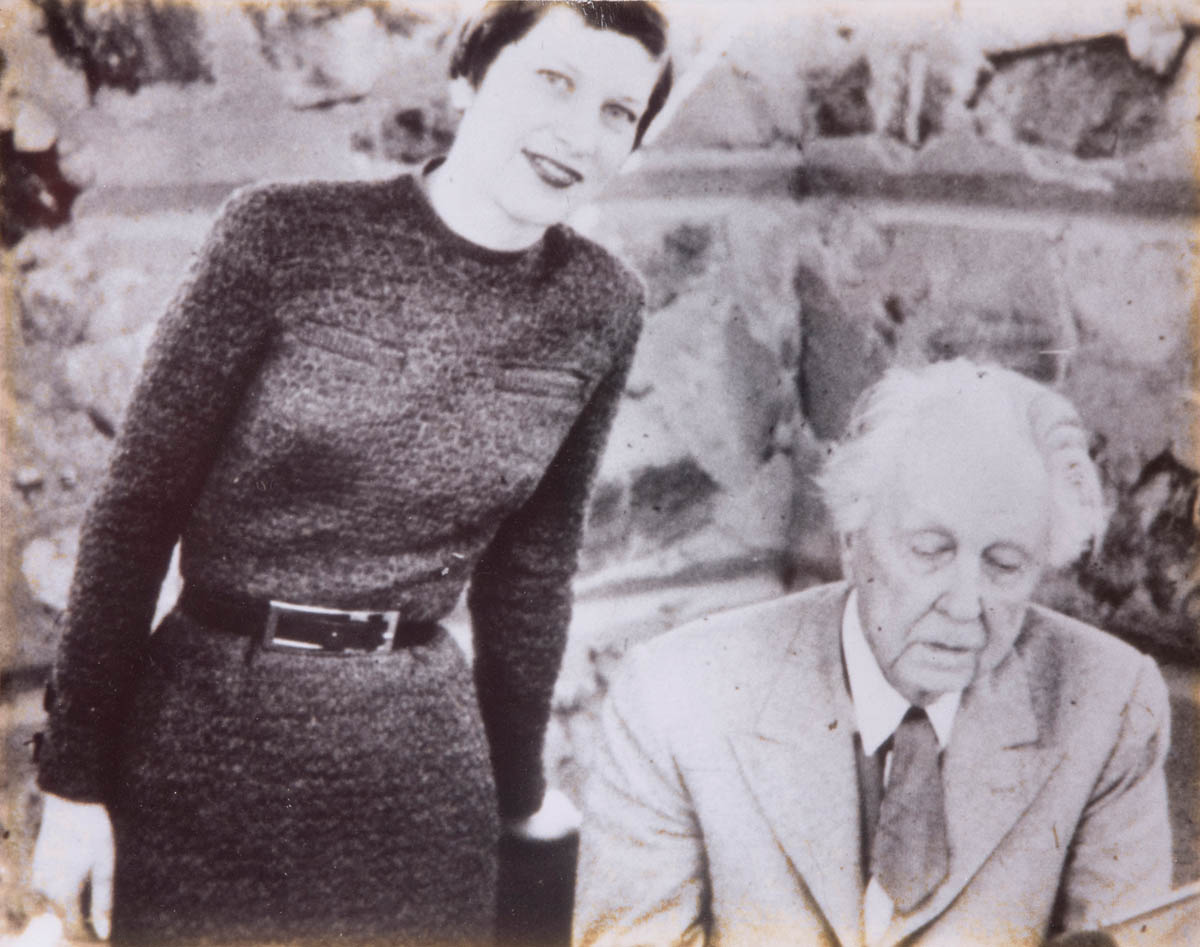

Millie Ablin and Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West, February 1959. Courtesy of Ablin Family Collection.

Ablin House, Bakersfield, California (1958–61), west façade.

Ablin House, wall of windows outside living room.

Wright’s chief draftsman, John Howe, wrote back promptly, asking for more information about the property and the Ablins’ requirements. So Millie sent him a topographical map and some 35 mm slides of the property. Wright’s executive secretary, Eugene Masselink, then responded with a letter telling them that “Mr. Wright” would draw up a preliminary set of plans for their house. After receiving these plans, Millie wrote another letter to Wright on January 7, 1959, asking him to make a total of 15 changes to his original design. Wright was famous for being resistant to making many changes in his plans (see the sections on the Buehler House in Chapter 5 and the Walker House in Chapter 6), so the Ablins had no way of knowing if he would accept their request. Among the changes they asked for were twin built-in beds in the master bedroom; double sinks in the master bathroom; carpeting in the adult living wing, living room, and dining area; extra storage cabinets throughout the house; and a fence around the pool in the backyard for the safety of their children. Of these items, Wright did agree to design the twin beds, the double sinks, and the extra storage throughout the home.[16]

In February 1959, Millie and George Ablin visited Frank Lloyd Wright at his studio at Taliesin West. During their visit he suggested they buy a second adjacent lot, so the house could be sited more appropriately, with the living room facing the golf course, and thus providing unspoiled views of the greenery around them. They followed his advice, and he agreed to design an extra bedroom in the children’s wing for their seventh child. Wright died on April 10, so the full set of working drawings were actually signed by Wes Peters in May 1959, even though the design of the house was clearly done by Wright himself.[17] The home was completed in 1961. The materials used in its construction were salmon-tinted concrete blocks on the walls, plate glass windows and doors, Philippine mahogany for framing and built-in furniture, wood shingles on the roof, and concrete slabs on the floors in four-by-four-foot patterns stained Cherokee red.

Ablin House, east façade.

The front of the Ablin House faces southeast, and it sits atop a gentle, grassy knoll, with the main entrance in the rear. The triangular-shaped swimming pool is surrounded by a concrete slab deck (but no fence). There is a grassy play area between the pool and the house, and a concrete slab terrace lining the rear walls. The low-gabled rooflines have wide overhanging eaves, which shelter the interior from the harsh Central Valley sun. The floor plan is in the shape of a modified “V,” with the entry hall and the kitchen at the apex. To the right, along a gallery-style hall, is a small study and the spacious master suite. To the left, adjoining another gallery, are the children’s bedrooms. The narrow entry hall, with its seven-foot-two-inch ceiling, opens into the huge living room, with a soaring ceiling that rises to a fourteen-foot-high peak at the southeast end. The roofline here forms a sharp projecting peak, a feature that Wright used on many of his post–World War II houses on the West Coast.

The most impressive feature of the living room is the 48-foot-wide wall of windows that undulates across the east end. These floor-to-ceiling windows allow this room to be flooded with natural light, and their wood framing, together with the built-in furniture, salmon-colored walls, and red floors, create a very warm and elegant ambience (though the specific tint used on the concrete block walls was a decision made by Taliesin Associated Architects shortly after Wright’s death).[18] Two sets of double wood-frame doors are set into this wall of glass, providing access to a spacious terrace surrounded by a low concrete border. In the northeast corner, Wright placed a dining area with a long built-in table and a set of 10 wooden chairs, all of which survive. The use of a far corner of the living room for dining gives this space a feeling of almost being a separate dining room. On the west wall is a wide fireplace. The ceiling is covered in sand-colored acoustic material. In the entry hall leading from the west side into the living room, Wright placed a built-in minibar, a feature requested by the Ablins. Besides the original dining set, the other existing wooden furniture in the living room, though designed by Wright, was not made until 1992 by Taliesin Associated Architects.[19]

Ablin House, dining area with Frank Lloyd Wright–designed table and chairs

Ablin House, full view of living room.

The most distinctive room in the Ablin House is the kitchen. Here, Wright created a space unlike any other he had designed for all of his West Coast houses. This room is contained inside a tall, irregularly shaped concrete cube, whose walls are pierced by dozens of repeated geometric patterns that are glazed on the inside. The effect this creates in the daytime is truly amazing, with the sunlight splashing onto the countertops and across the wide workspace. The appliances here are all original, as are the countertops covered in pink tiles.

The master bedroom and bath are both unusually spacious, compared with most of the other homes Wright designed on the West Coast in the 1950s. There are built-in bookcases and shelves along the walls of the master bedroom, and the bathroom fixtures are all original. The hallway connecting the master suite to the entry area is also quite spacious, with storage cabinets along the walls. Wright also placed storage cabinets all along the walls of the hallway that leads to the children’s bedrooms, as well as designing built-in bookshelves and desks in these bedrooms. A three-car carport runs off the northwest corner of the house, and it connects to a small storage room. The wide overhanging eaves that run around the entire perimeter of the house provide protection from the weather when walking from the carport to the main entrance.

George and Mildred Ablin lived happily in their house for the rest of their lives. They raised seven children there: four sons and three daughters. George died in 1999, and Millie passed away about 2002. A few years later, the house was sold to its current owner, Michael Glick, who has maintained the home in its original condition. The house is occasionally used as a meeting place for various professional groups and conferences, as well as for research by Wright scholars.[20] Thus, the George Ablin House has been preserved as an invaluable cultural resource, and an intact treasure of America’s twentieth-century architectural legacy.

Ablin House, west façade with pool.

Ablin House, kitchen.