Sorting is a snap in Java. You have all the tools for collecting and manipulating your data without having to write your own sort algorithms (unless you’re reading this right now sitting in your Computer Science 101 class, in which case, trust us—you are SO going to be writing sort code while the rest of us just call a method in the Java API). The Java Collections Framework has a data structure that should work for virtually anything you’ll ever need to do. Want to keep a list that you can easily keep adding to? Want to find something by name? Want to create a list that automatically takes out all the duplicates? Sort your co-workers by the number of times they’ve stabbed you in the back? Sort your pets by number of tricks learned? It’s all here...

Congratulations on your new job—managing the automated jukebox system at Lou’s Diner. There’s no Java inside the jukebox itself, but each time someone plays a song, the song data is appended to a simple text file.

Your job is to manage the data to track song popularity, generate reports, and manipulate the playlists. You’re not writing the entire app—some of the other software developer/ waiters are involved as well, but you’re responsible for managing and sorting the data inside the Java app. And since Lou has a thing against databases, this is strictly an in-memory data collection. All you get is the file the jukebox keeps adding to. Your job is to take it from there.

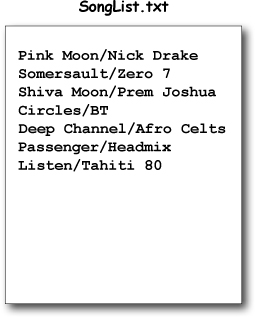

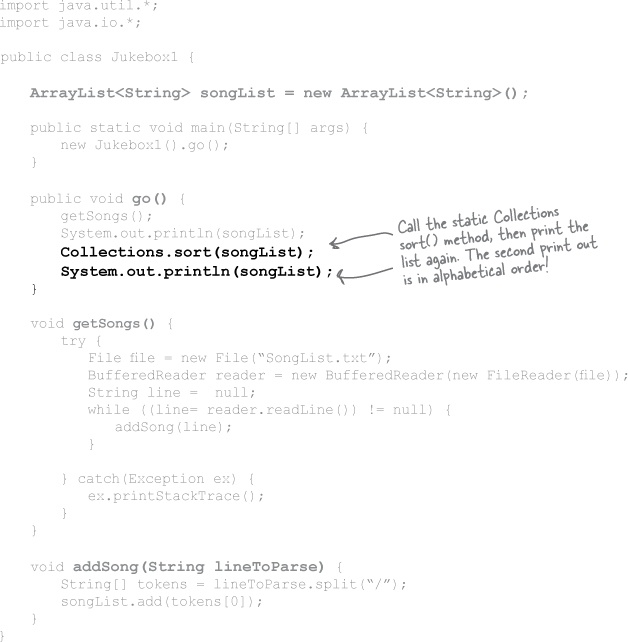

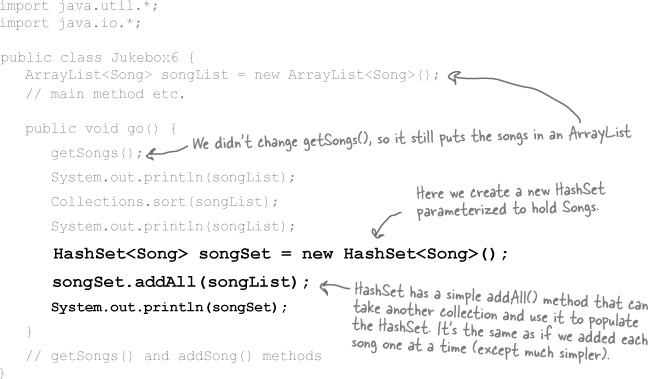

You’ve already figured out how to read and parse the file, and so far you’ve been storing the data in an ArrayList.

Challenge #1 Sort the songs in alphabetical order

You have a list of songs in a file, where each line represents one song, and the title and artist are separated with a forward slash. So it should be simple to parse the line, and put all the songs in an ArrayList.

Your boss cares only about the song titles, so for now you can simply make a list that just has the song titles.

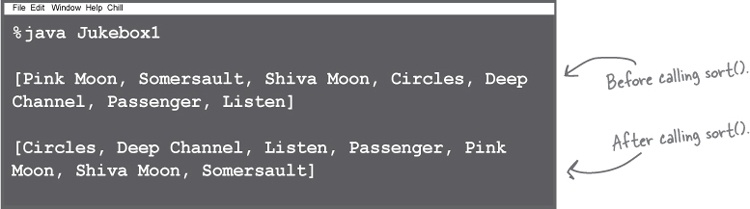

But you can see that the list is not in alphabetical order... what can you do?

You know that with an ArrayList, the elements are kept in the order in which they were inserted into the list, so putting them in an ArrayList won’t take care of alphabetizing them, unless... maybe there’s a sort() method in the ArrayList class?

When you look in ArrayList, there doesn’t seem to be any method related to sorting. Walking up the inheritance hierarchy didn’t help either—it’s clear that you can’t call a sort method on the ArrayList.

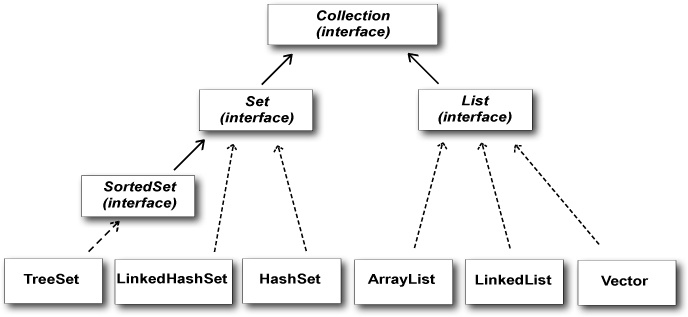

Although ArrayList is the one you’ll use most often, there are others for special occasions. Some of the key collection classes include:

Note

Don’t worry about trying to learn these other ones right now. We’ll go into more details a little later.

TreeSet

Keeps the elements sorted and prevents duplicates.

HashMap

Lets you store and access elements as name/value pairs.

LinkedList

Makes it easy to create structures like stacks or queues.

HashSet

Prevents duplicates in the collection, and given an element, can find that element in the collection quickly.

LinkedHashMap

Like a regular HashMap, except it can remember the order in which elements (name/value pairs) were inserted, or it can be configured to remember the order in which elements were last accessed.

If you put all the Strings (the song titles) into a TreeSet instead of an ArrayList, the Strings would automatically land in the right place, alphabetically sorted. Whenever you printed the list, the elements would always come out in alphabetical order.

And that’s great when you need a set (we’ll talk about sets in a few minutes) or when you know that the list must always stay sorted alphabetically.

On the other hand, if you don’t need the list to stay sorted, TreeSet might be more expensive than you need—every time you insert into a TreeSet, the TreeSet has to take the time to figure out where in the tree the new element must go. With ArrayList, inserts can be blindingly fast because the new element just goes in at the end.

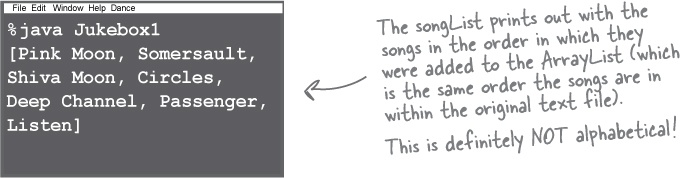

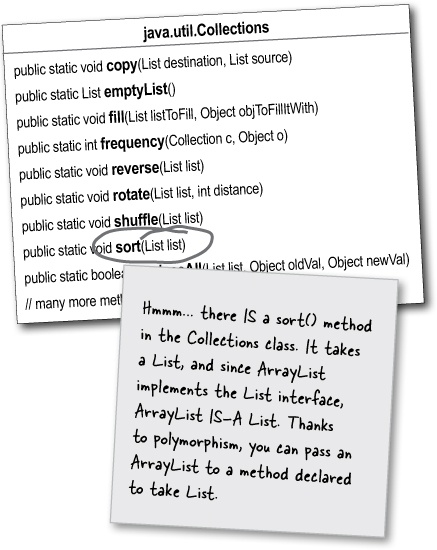

The Collections.sort() method sorts a list of Strings alphabetically.

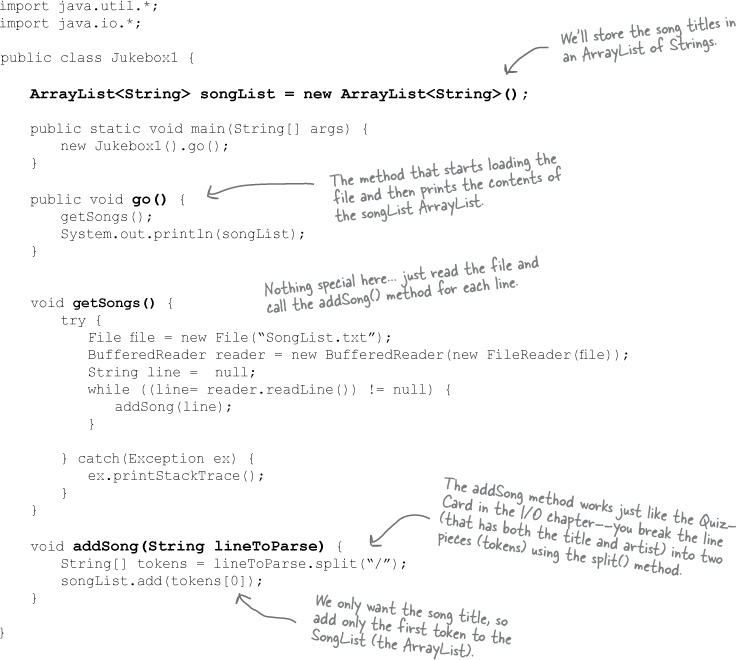

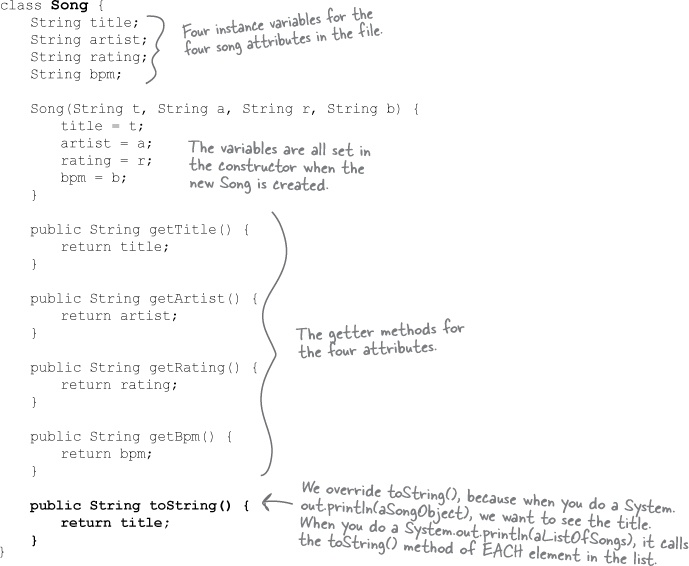

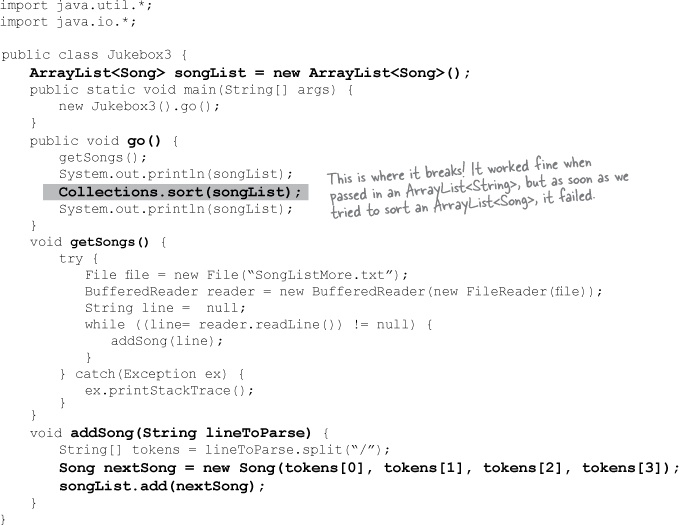

Now your boss wants actual Song class instances in the list, not just Strings, so that each Song can have more data. The new jukebox device outputs more information, so this time the file will have four pieces (tokens) instead of just two.

The Song class is really simple, with only one interesting feature—the overridden toString() method. Remember, the toString() method is defined in class Object, so every class in Java inherits the method. And since the toString() method is called on an object when it’s printed (System.out.println(anObject)), you should override it to print something more readable than the default unique identifier code. When you print a list, the toString() method will be called on each object.

Your code changes only a little—the file I/O code is the same, and the parsing is the same (String.split()), except this time there will be four tokens for each song/line, and all four will be used to create a new Song object. And of course the ArrayList will be of type <Song> instead of <String>.

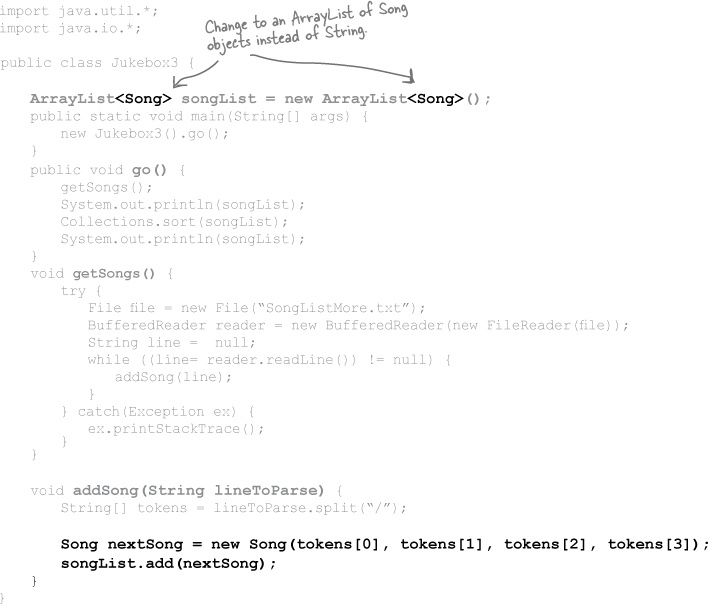

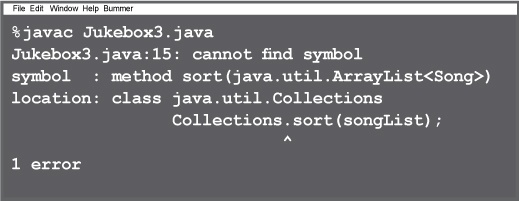

Something’s wrong... the Collections class clearly shows there’s a sort() method, that takes a List.

ArrayList is-a List, because ArrayList implements the List interface, so... it should work.

But it doesn’t!

The compiler says it can’t find a sort method that takes an ArrayList<Song>, so maybe it doesn’t like an ArrayList of Song objects? It didn’t mind an ArrayList<String>, so what’s the important difference between Song and String? What’s the difference that’s making the compiler fail?

And of course you probably already asked yourself, “What would it be sorting on?” How would the sort method even know what made one Song greater or less than another Song? Obviously if you want the song’s title to be the value that determines how the songs are sorted, you’ll need some way to tell the sort method that it needs to use the title and not, say, the beats per minute.

We’ll get into all that a few pages from now, but first, let’s find out why the compiler won’t even let us pass a Song ArrayList to the sort() method.

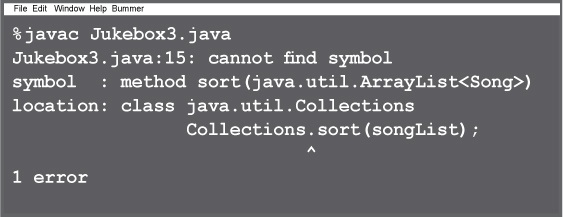

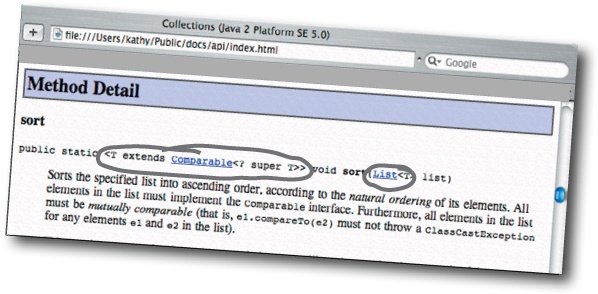

From the API docs (looking up the java.util.Collections class, and scrolling to the sort() method), it looks like the sort() method is declared... strangely. Or at least different from anything we’ve seen so far.

That’s because the sort() method (along with other things in the whole collection framework in Java) makes heavy use of generics. Anytime you see something with angle brackets in Java source code or documentation, it means generics—a feature added to Java 5.0. So it looks like we’ll have to learn how to interpret the documentation before we can figure out why we were able to sort String objects in an ArrayList, but not an ArrayList of Song objects.

We’ll just say it right here—virtually all of the code you write that deals with generics will be collection-related code. Although generics can be used in other ways, the main point of generics is to let you write type-safe collections. In other words, code that makes the compiler stop you from putting a Dog into a list of Ducks.

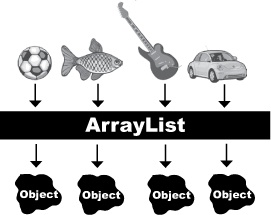

Before generics (which means before Java 5.0), the compiler could not care less what you put into a collection, because all collection implementations were declared to hold type Object. You could put anything in any ArrayList; it was like all ArrayLists were declared as ArrayList<Object>.

With generics, you can create type-safe collections where more problems are caught at compile-time instead of runtime.

Without generics, the compiler would happily let you put a Pumpkin into an ArrayList that was supposed to hold only Cat objects.

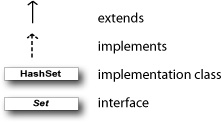

WITHOUT generics

Objects go IN as a reference to SoccerBall, Fish, Guitar, and Car objects

And come OUT as a reference of type Object

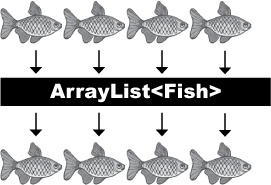

WITH generics

Objects go IN as a reference to only Fish objects

And come out as a reference of type Fish

Of the dozens of things you could learn about generics, there are really only three that matter to most programmers:

Creating instances of generified classes (like ArrayList)

When you make an ArrayList, you have to tell it the type of objects you’ll allow in the list, just as you do with plain old arrays.

new ArrayList<Song>()Declaring and assigning variables of generic types

How does polymorphism really work with generic types? If you have an ArrayList<Animal> reference variable, can you assign an ArrayList<Dog> to it? What about a List<Animal> reference? Can you assign an ArrayList<Animal> to it? You’ll see...

List<Song> songList = new ArrayList<Song>()

Declaring (and invoking) methods that take generic types

If you have a method that takes as a parameter, say, an ArrayList of Animal objects, what does that really mean? Can you also pass it an ArrayList of Dog objects? We’ll look at some subtle and tricky polymorphism issues that are very different from the way you write methods that take plain old arrays.

(This is actually the same point as #2, but that shows you how important we think it is.)

void foo(List<Song> list) x.foo(songList)

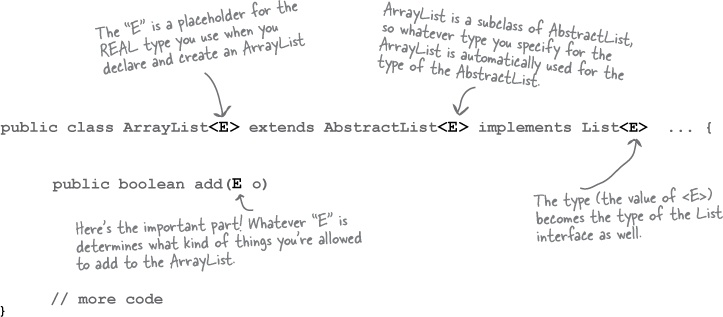

Since ArrayList is our most-used generified type, we’ll start by looking at its documentation. The two key areas to look at in a generified class are:

1) The class declaration

2) The method declarations that let you add elements

Think of “E” as a stand-in for “the type of element you want this collection to hold and return.” (E is for Element.)

Understanding ArrayList documentation (Or, what’s the true meaning of “E”?)

The “E” represents the type used to create an instance of ArrayList. When you see an “E” in the ArrayList documentation, you can do a mental find/replace to exchange it for whatever <type> you use to instantiate ArrayList.

So, new ArrayList<Song> means that “E” becomes “Song”, in any method or variable declaration that uses “E”.

In other words, the “E” is replaced by the real type (also called the type parameter) that you use when you create the ArrayList. And that’s why the add() method for ArrayList won’t let you add anything except objects of a reference type that’s compatible with the type of “E”. So if you make an ArrayList<String>, the add() method suddenly becomes add(String o). If you make the ArrayList of type Dog, suddenly the add() method becomes add(Dog o).

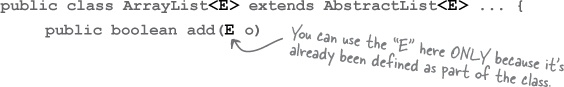

A generic class means that the class declaration includes a type parameter. A generic method means that the method declaration uses a type parameter in its signature.

You can use type parameters in a method in several different ways:

Using a type parameter defined in the class declaration

When you declare a type parameter for the class, you can simply use that type any place that you’d use a real class or interface type. The type declared in the method argument is essentially replaced with the type you use when you instantiate the class.

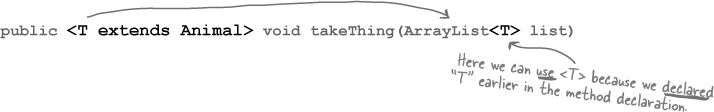

Using a type parameter that was NOT defined in the class declaration

If the class itself doesn’t use a type parameter, you can still specify one for a method, by declaring it in a really unusual (but available) space—before the return type. This method says that T can be “any type of Animal”.

This:

public <T extends Animal> void takeThing(ArrayList<T> list)

Is NOT the same as this:

public void takeThing(ArrayList<Animal> list)Both are legal, but they’re different!

The first one, where <T extends Animal> is part of the method declaration, means that any ArrayList declared of a type that is Animal, or one of Animal’s subtypes (like Dog or Cat), is legal. So you could invoke the top method using an ArrayList<Dog>, ArrayList<Cat>, or ArrayList<Animal>.

But... the one on the bottom, where the method argument is (ArrayList<Animal> list) means that only an ArrayList<Animal> is legal. In other words, while the first version takes an ArrayList of any type that is a type of Animal (Animal, Dog, Cat, etc.), the second version takes only an ArrayList of type Animal. Not ArrayList<Dog>, or ArrayList<Cat> but only ArrayList<Animal>.

And yes, it does appear to violate the point of polymorphism. but it will become clear when we revisit this in detail at the end of the chapter. For now, remember that we’re only looking at this because we’re still trying to figure out how to sort() that SongList, and that led us into looking at the API for the sort() method, which had this strange generic type declaration.

For now, all you need to know is that the syntax of the top version is legal, and that it means you can pass in a ArrayList object instantiated as Animal or any Animal subtype.

And now back to our sort() method...

Remember where we were...

So here we are, trying to read the sort() method docs to find out why it was OK to sort a list of Strings, but not a list of Song objects. And it looks like the answer is...

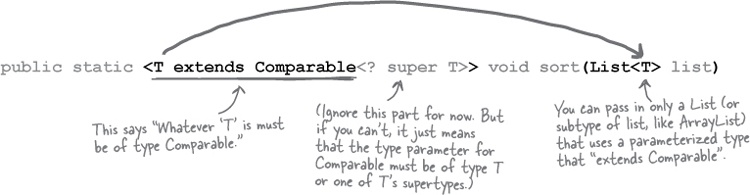

The sort() method can take only lists of Comparable objects.

Song is NOT a subtype of Comparable, so you cannot sort() the list of Songs.

At least not yet...

public final class String extends Object implements Serializable, Comparable<String>, CharSequence

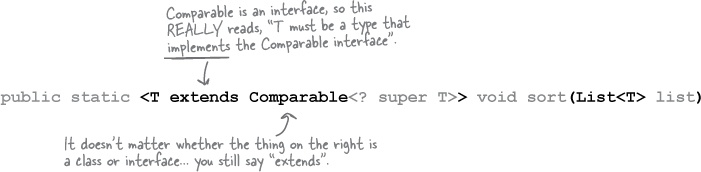

The Java engineers had to give you a way to put a constraint on a parameterized type, so that you can restrict it to, say, only subclasses of Animal. But you also need to constrain a type to allow only classes that implement a particular interface. So here’s a situation where we need one kind of syntax to work for both situations—inheritance and implementation. In other words, that works for both extends and implements.

And the winning word was... extends. But it really means “is-a”, and works regardless of whether the type on the right is an interface or a class.

In generics, the keyword “extends” really means “is-a”, and works for BOTH classes and interfaces.

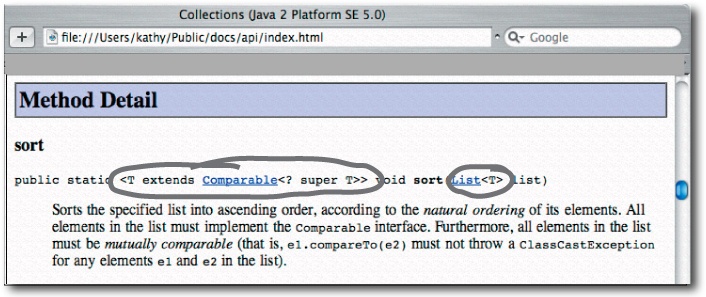

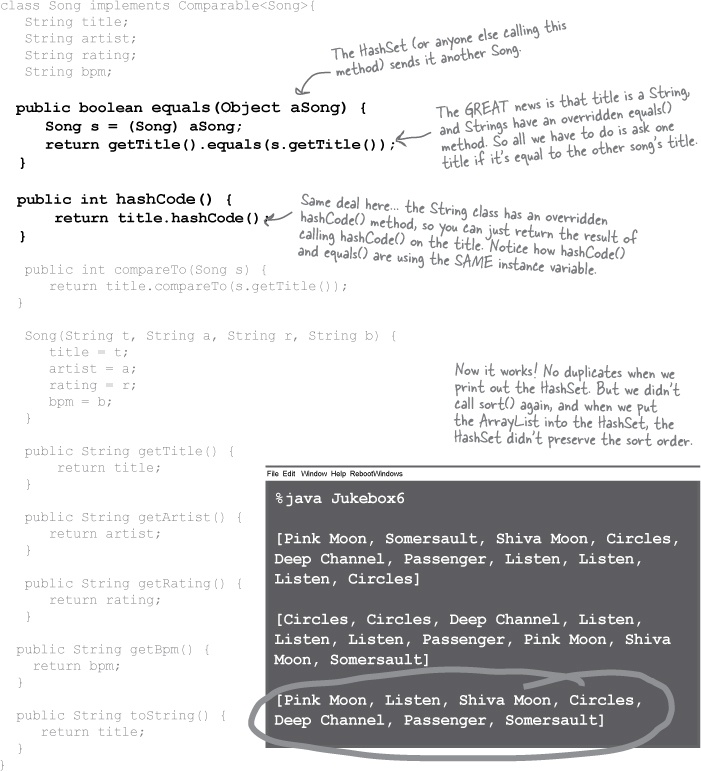

We can pass the ArrayList<Song> to the sort() method only if the Song class implements Comparable, since that’s the way the sort() method was declared. A quick check of the API docs shows the Comparable interface is really simple, with only one method to implement:

The big question is: what makes one song less than, equal to, or greater than another song?

You can’t implement the Comparable interface until you make that decision.

And the method documentation for compareTo() says

It looks like the compareTo() method will be called on one Song object, passing that Song a reference to a different Song. The Song running the compareTo() method has to figure out if the Song it was passed should be sorted higher, lower, or the same in the list.

Your big job now is to decide what makes one song greater than another, and then implement the compareTo() method to reflect that. A negative number (any negative number) means the Song you were passed is greater than the Song running the method. Returning a positive number says that the Song running the method is greater than the Song passed to the compareTo() method. Returning zero means the Songs are equal (at least for the purpose of sorting... it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the same object). You might, for example, have two Songs with the same title.

(Which brings up a whole different can of worms we’ll look at later...)

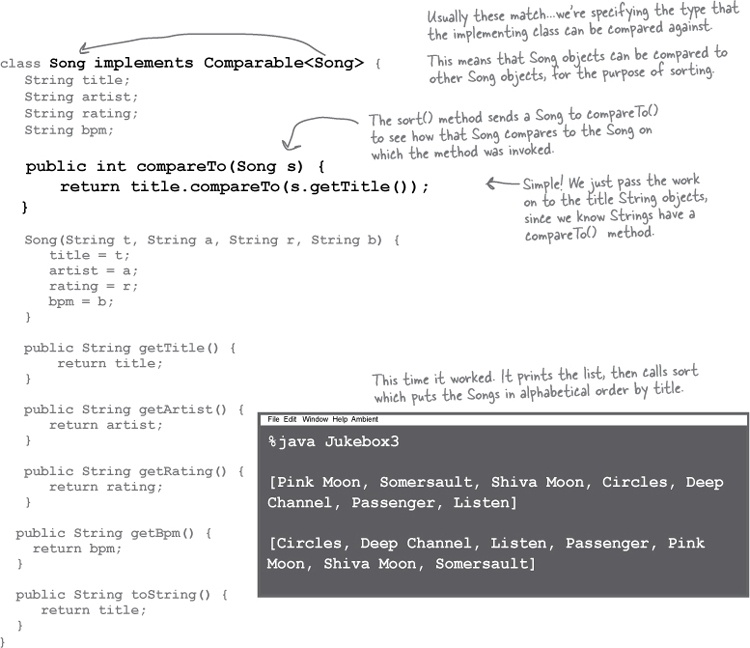

We decided we want to sort by title, so we implement the compareTo() method to compare the title of the Song passed to the method against the title of the song on which the compareTo() method was invoked. In other words, the song running the method has to decide how its title compares to the title of the method parameter.

Hmmm... we know that the String class must know about alphabetical order, because the sort() method worked on a list of Strings. We know String has a compareTo() method, so why not just call it? That way, we can simply let one title String compare itself to another, and we don’t have to write the comparing/alphabetizing algorithm!

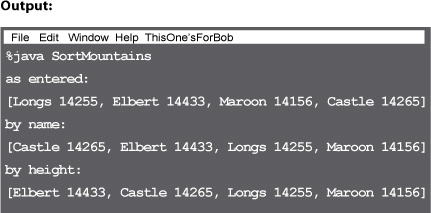

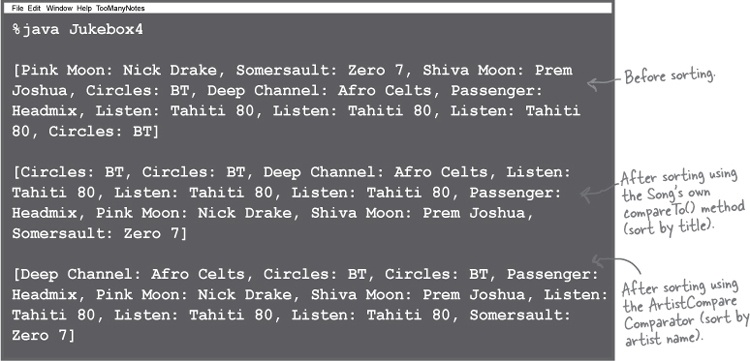

There’s a new problem—Lou wants two different views of the song list, one by song title and one by artist!

But when you make a collection element comparable (by having it implement Comparable), you get only one chance to implement the compareTo() method. So what can you do?

The horrible way would be to use a flag variable in the Song class, and then do an if test in compareTo() and give a different result depending on whether the flag is set to use title or artist for the comparison.

But that’s an awful and brittle solution, and there’s something much better. Something built into the API for just this purpose—when you want to sort the same thing in more than one way.

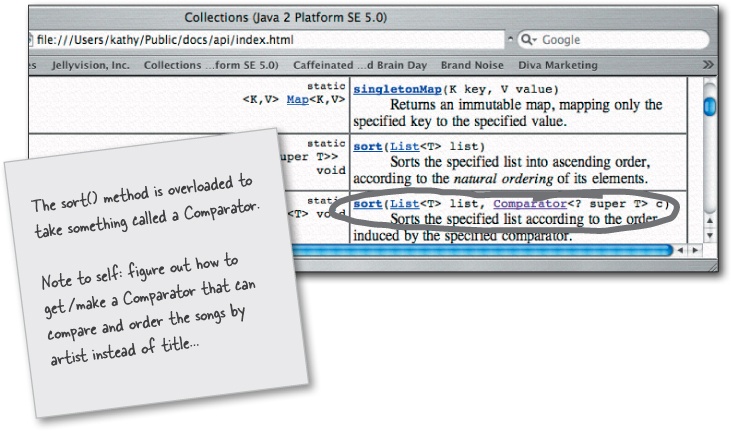

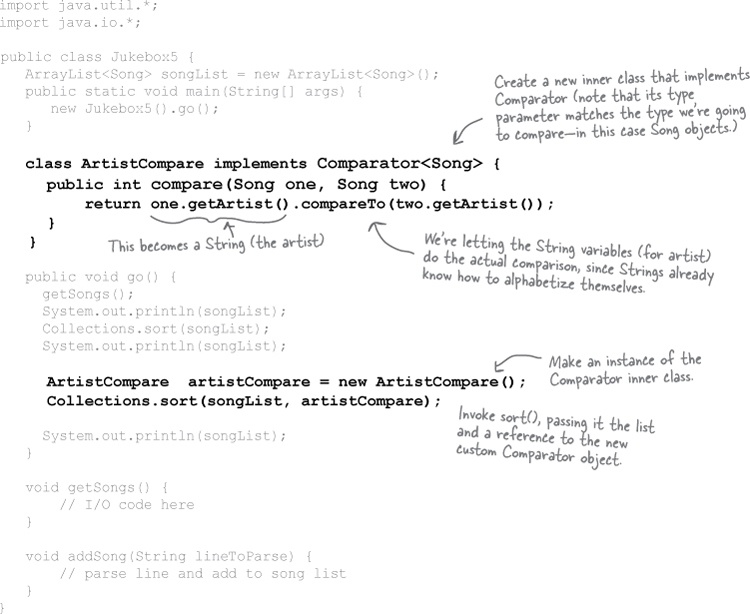

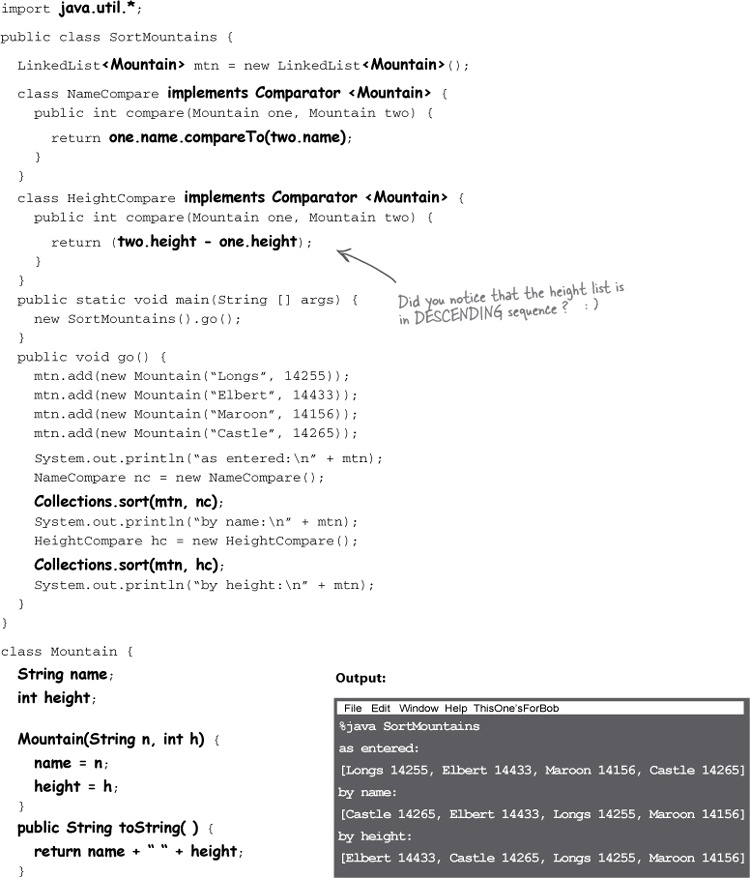

Look at the Collections class API again. There’s a second sort() method—and it takes a Comparator.

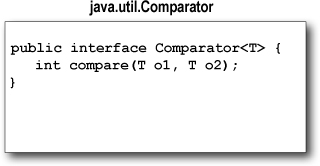

An element in a list can compare itself to another of its own type in only one way, using its compareTo() method. But a Comparator is external to the element type you’re comparing—it’s a separate class. So you can make as many of these as you like! Want to compare songs by artist? Make an ArtistComparator. Sort by beats per minute? Make a BPMComparator.

If you pass a Comparator to the sort() method, the sort order is determined by the Comparator rather than the element’s own compareTo() method.

Then all you need to do is call the overloaded sort() method that takes the List and the Comparator that will help the sort() method put things in order.

The sort() method that takes a Comparator will use the Comparator instead of the element’s own compareTo() method, when it puts the elements in order. In other words, if your sort() method gets a Comparator, it won’t even call the compareTo() method of the elements in the list. The sort() method will instead invoke the compare() method on the Comparator.

So, the rules are:

Invoking the one-argument sort(List o) method means the list element’s compareTo() method determines the order. So the elements in the list MUST implement the Comparable interface.

Invoking sort(List o, Comparator c) means the list element’s compareTo() method will NOT be called, and the Comparator’s compare() method will be used instead. That means the elements in the list do NOT need to implement the Comparable interface.

We did three new things in this code:

1) Created an inner class that implements Comparator (and thus the compare() method that does the work previously done by compareTo()).

2) Made an instance of the Comparator inner class.

3) Called the overloaded sort() method, giving it both the song list and the instance of the Comparator inner class.

Note: we also updated the Song class toString() method to print both the song title and the artist. (It prints title: artist regardless of how the list is sorted.)

Note

Note: we’ve made sort-by-title the default sort, by keeping the compareTo() method in Song use the titles. But another way to design this would be to implement both the title sorting and artist sorting as inner Comparator classes, and not have Song implement Comparable at all. That means we’d always use the twoarg version of Collections.sort().

The sorting works great, now we know how to sort on both title (using the Song object’s compareTo() method) and artist (using the Comparator’s compare() method). But there’s a new problem we didn’t notice with a test sample of the jukebox text file—the sorted list contains duplicates.

It appears that the diner jukebox just keeps writing to the file regardless of whether the same song has already been played (and thus written) to the text file. The SongListMore.txt jukebox text file is a complete record of every song that was played, and might contain the same song multiple times.

The SongListMore text file now has duplicates in it, because the jukebox machine is writing every song played, in order. Somebody decided to play “Listen” three times in a row, followed by “Circles”, a song that had been played earlier.

We can’t change the way the text file is written because sometimes we’re going to need all that information. We have to change the java code.

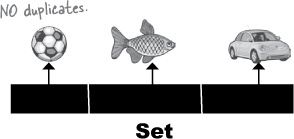

From the Collection API, we find three main interfaces, List, Set, and Map. ArrayList is a List, but it looks like Set is exactly what we need.

LIST - when sequence matters

Collections that know about index position.

Lists know where something is in the list. You can have more than one element referencing the same object.

SET - when uniqueness matters

Collections that do not allow duplicates.

Sets know whether something is already in the collection. You can never have more than one element referencing the same object (or more than one element referencing two objects that are considered equal—we’ll look at what object equality means in a moment).

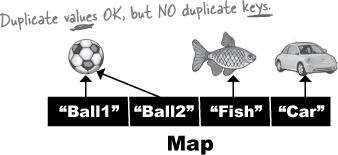

MAP - when finding something by key matters

Collections that use key-value pairs.

Maps know the value associated with a given key. You can have two keys that reference the same value, but you cannot have duplicate keys. Although keys are typically String names (so that you can make name/value property lists, for example), a key can be any object.

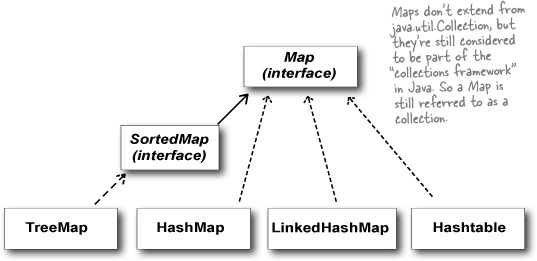

Notice that the Map interface doesn’t actually extend the Collection interface, but Map is still considered part of the “Collection Framework” (also known as the “Collection API”). So Maps are still collections, even though they don’t include java.util.Collection in their inheritance tree.

(Note: this is not the complete collection API; there are other classes and interfaces, but these are the ones we care most about.)

We added on to the Jukebox to put the songs in a HashSet. (Note: we left out some of the Jukebox code, but you can copy it from earlier versions. And to make it easier to read the output, we went back to the earlier version of the Song’s toString() method, so that it prints only the title instead of title and artist.)

First, we have to ask—what makes two Song references duplicates? They must be considered equal. Is it simply two references to the very same object, or is it two separate objects that both have the same title?

This brings up a key issue: reference equality vs. object equality.

Note

If two objects foo and bar are equal, foo.equals(bar) must be true, and both foo and bar must return the same value from hashCode(). For a Set to treat two objects as duplicates, you must override the hashCode() and equals() methods inherited from class Object, so that you can make two different objects be viewed as equal.

Reference equality

Two references, one object on the heap.

Two references that refer to the same object on the heap are equal. Period. If you call the hashCode() method on both references, you’ll get the same result. If you don’t override the hashCode() method, the default behavior (remember, you inherited this from class Object) is that each object will get a unique number (most versions of Java assign a hashcode based on the object’s memory address on the heap, so no two objects will have the same hashcode).

If you want to know if two references are really referring to the same object, use the == operator, which (remember) compares the bits in the variables. If both references point to the same object, the bits will be identical.

if (foo == bar) { // both references are referring // to the same object on the heap }Object equality

Two references, two objects on the heap, but the objects are considered meaningfully equivalent.

If you want to treat two different Song objects as equal (for example if you decided that two Songs are the same if they have matching title variables), you must override both the hashCode() and equals() methods inherited from class Object.

As we said above, if you don’t override hashCode(), the default behavior (from Object) is to give each object a unique hashcode value. So you must override hashCode() to be sure that two equivalent objects return the same hashcode. But you must also override equals() so that if you call it on either object, passing in the other object, always returns true.

if (foo.equals(bar) && foo.hashCode() == bar.hashCode()) { // both references are referring to either a // a single object, or to two objects that are equal }

When you put an object into a Hashset, it uses the object’s hashcode value to determine where to put the object in the Set. But it also compares the object’s hashcode to the hashcode of all the other objects in the HashSet, and if there’s no matching hashcode, the HashSet assumes that this new object is not a duplicate.

In other words, if the hashcodes are different, the HashSet assumes there’s no way the objects can be equal!

So you must override hashCode() to make sure the objects have the same value.

But two objects with the same hashCode() might not be equal (more on this on the next page), so if the HashSet finds a matching hashcode for two objects—one you’re inserting and one already in the set—the HashSet will then call one of the object’s equals() methods to see if these hashcode-matched objects really are equal.

And if they’re equal, the HashSet knows that the object you’re attempting to add is a duplicate of something in the Set, so the add doesn’t happen.

You don’t get an exception, but the HashSet’s add() method returns a boolean to tell you (if you care) whether the new object was added. So if the add() method returns false, you know the new object was a duplicate of something already in the set.

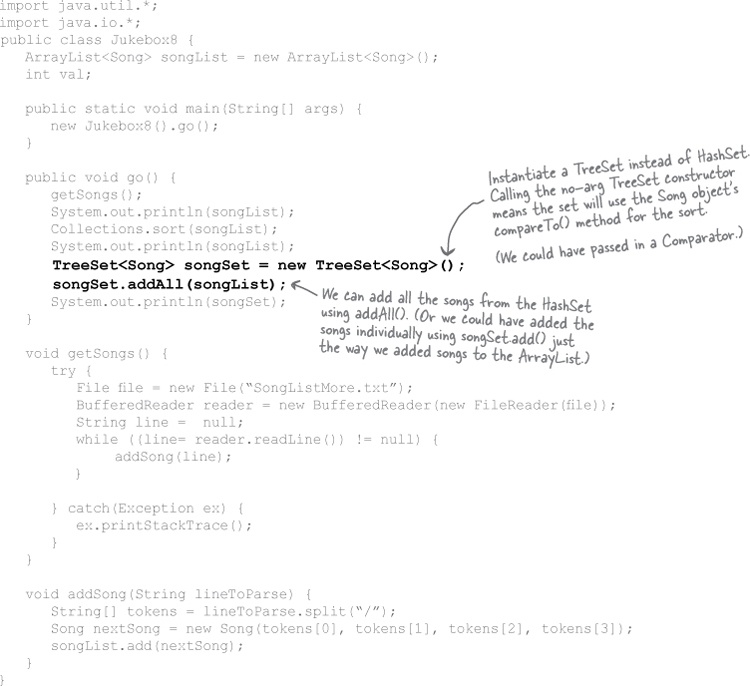

TreeSet is similar to HashSet in that it prevents duplicates. But it also keeps the list sorted. It works just like the sort() method in that if you make a TreeSet using the set’s no-arg constructor, the TreeSet uses each object’s compareTo() method for the sort. But you have the option of passing a Comparator to the TreeSet constructor, to have the TreeSet use that instead. The downside to TreeSet is that if you don’t need sorting, you’re still paying for it with a small performance hit. But you’ll probably find that the hit is almost impossible to notice for most apps.

TreeSet looks easy, but make sure you really understand what you need to do to use it. We thought it was so important that we made it an exercise so you’d have to think about it. Do NOT turn the page until you’ve done this. We mean it.

TreeSet can’t read the programmer’s mind to figure out how the objects should be sorted. You have to tell the TreeSet how.

To use a TreeSet, one of these things must be true:

The elements in the list must be of a type that implements Comparable

The Book class on the previous page didn’t implement Comparable, so it wouldn’t work at runtime. Think about it, the poor TreeSet’s sole purpose in life is to keep your elements sorted, and once again—it had no idea how to sort Book objects! It doesn’t fail at compile-time, because the TreeSet add() method doesn’t take a Comparable type,The TreeSet add() method takes whatever type you used when you created the TreeSet. In other words, if you say new TreeSet<Book>() the add() method is essentially add(Book). And there’s no requirement that the Book class implement Comparable! But it fails at runtime when you add the second element to the set. That’s the first time the set tries to call one of the object’s compareTo() methods and... can’t.

class Book implements Comparable { String title; public Book(String t) { title = t; } public int compareTo(Object b) { Book book = (Book) b; return (title.compareTo(book.title)); } }

OR

You use the TreeSet’s overloaded constructor that takes a Comparator

TreeSet works a lot like the sort() method—you have a choice of using the element’s compareTo() method, assuming the element type implemented the Comparable interface, OR you can use a custom Comparator that knows how to sort the elements in the set. To use a custom Comparator, you call the TreeSet constructor that takes a Comparator.

public class BookCompare implements Comparator<Book> { public int compare(Book one, Book two) { return (one.title.compareTo(two.title)); } } class Test { public void go() { Book b1 = new Book("How Cats Work"); Book b2 = new Book("Remix your Body"); Book b3 = new Book("Finding Emo"); BookCompare bCompare = new BookCompare(); TreeSet<Book> tree = new TreeSet<Book>(bCompare); tree.add(new Book("How Cats Work"); tree.add(new Book("Finding Emo"); tree.add(new Book("Remix your Body"); System.out.println(tree); } }

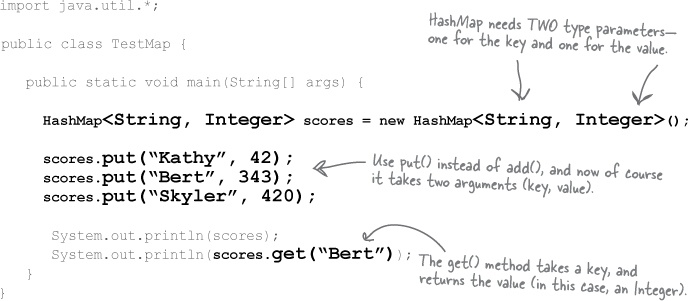

Lists and Sets are great, but sometimes a Map is the best collection (not Collection with a capital “C”—remember that Maps are part of Java collections but they don’t implement the Collection interface).

Imagine you want a collection that acts like a property list, where you give it a name and it gives you back the value associated with that name. Although keys will often be Strings, they can be any Java object (or, through autoboxing, a primitive).

Map example

Remember earlier in the chapter we talked about how methods that take arguments with generic types can be... weird. And we mean weird in the polymorphic sense. If things start to feel strange here, just keep going—it takes a few pages to really tell the whole story.

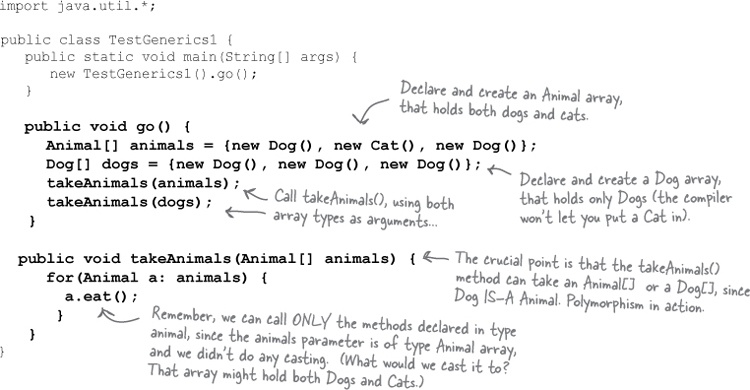

We’ll start with a reminder on how array arguments work, polymorphically, and then look at doing the same thing with generic lists. The code below compiles and runs without errors:

Note

If a method argument is an array of Animals, it will also take an array of any Animal subtype.

In other words, if a method is declared as:

void foo(Animal[] a) { }

Assuming Dog extends Animal, you are free to call both:

foo(anAnimalArray); foo(aDogArray);

Here’s how it works with regular arrays:

abstract class Animal {

void eat() {

System.out.println("animal eating");

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

void bark() { }

}

class Cat extends Animal {

void meow() { }

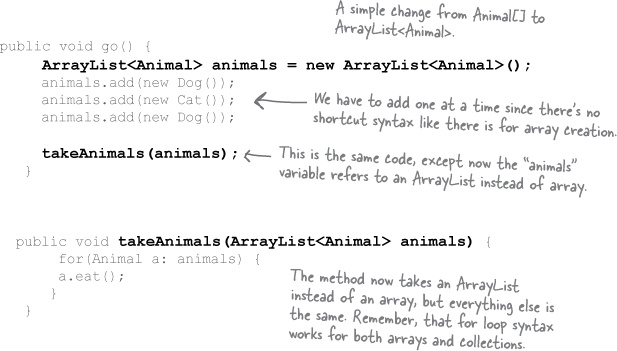

}So we saw how the whole thing worked with arrays, but will it work the same way when we switch from an array to an ArrayList? Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it?

First, let’s try it with only the Animal ArrayList. We made just a few changes to the go() method:

Passing in just ArrayList<Animal>

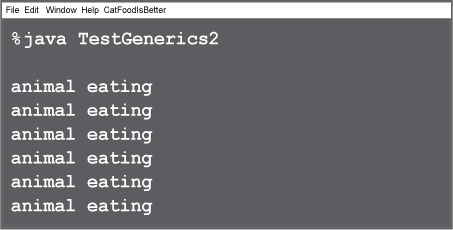

Compiles and runs just fine

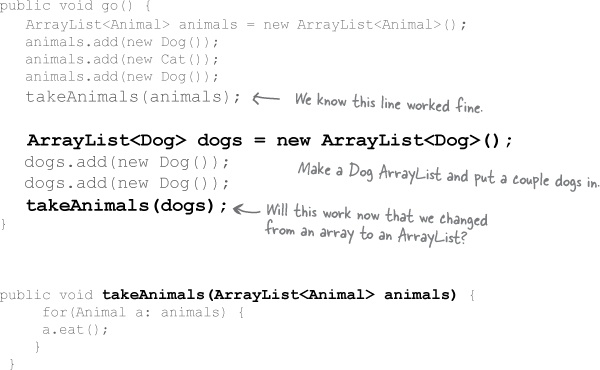

Because of polymorphism, the compiler let us pass a Dog array to a method with an Animal array argument. No problem. And an ArrayList<Animal> can be passed to a method with an ArrayList<Animal> argument. So the big question is, will the ArrayList<Animal> argument accept an ArrayList<Dog>? If it works with arrays, shouldn’t it work here too?

Passing in just ArrayList<Dog>

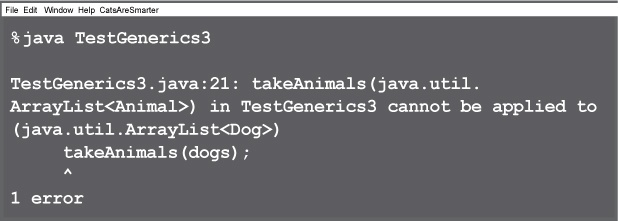

When we compile it:

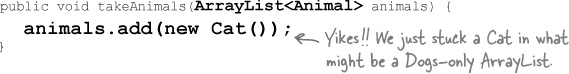

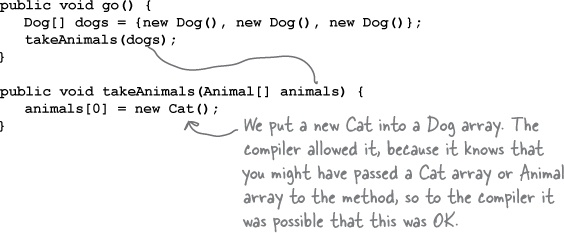

Imagine the compiler let you get away with that. It let you pass an ArrayList<Dog> to a method declared as:

public void takeAnimals(ArrayList<Animal> animals) {

for(Animal a: animals) {

a.eat();

}

}There’s nothing in that method that looks harmful, right? After all, the whole point of polymorphism is that anything an Animal can do (in this case, the eat() method), a Dog can do as well. So what’s the problem with having the method call eat() on each of the Dog references?

Nothing. Nothing at all.

There’s nothing wrong with that code. But imagine this code instead:

So that’s the problem. There’s certainly nothing wrong with adding a Cat to an ArrayList<Animal>, and that’s the whole point of having an ArrayList of a supertype like Animal—so that you can put all types of animals in a single Animal ArrayList.

But if you passed a Dog ArrayList—one meant to hold ONLY Dogs—to this method that takes an Animal ArrayList, then suddenly you’d end up with a Cat in the Dog list. The compiler knows that if it lets you pass a Dog ArrayList into the method like that, someone could, at runtime, add a Cat to your Dog list. So instead, the compiler just won’t let you take the risk.

If you declare a method to take ArrayList<Animal> it can take ONLY an ArrayList<Animal>, not ArrayList<Dog> or ArrayList<Cat>.

Array types are checked again at runtime, but collection type checks happen only when you compile

Let’s say you do add a Cat to an array declared as Dog[] (an array that was passed into a method argument declared as Animal[], which is a perfectly legal assignment for arrays).

It compiles, but when we run it:

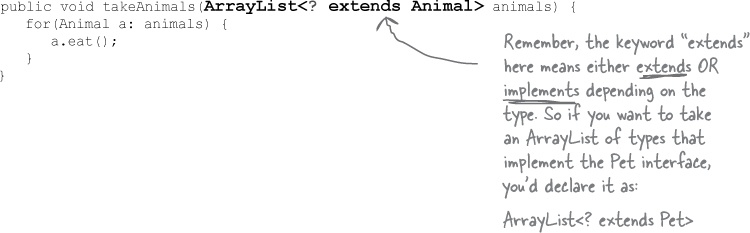

It looks unusual, but there is a way to create a method argument that can accept an ArrayList of any Animal subtype. The simplest way is to use a wildcard—added to the Java language explicitly for this reason.

So now you’re wondering, “What’s the difference? Don’t you have the same problem as before? The method above isn’t doing anything dangerous—calling a method any Animal subtype is guaranteed to have—but can’t someone still change this to add a Cat to the animals list, even though it’s really an ArrayList<Dog>? And since it’s not checked again at runtime, how is this any different from declaring it without the wildcard?”

And you’d be right for wondering. The answer is NO. When you use the wildcard <?> in your declaration, the compiler won’t let you do anything that adds to the list!

Note

When you use a wildcard in your method argument, the compiler will STOP you from doing anything that could hurt the list referenced by the method parameter.

You can still invoke methods on the elements in the list, but you cannot add elements to the list.

In other words, you can do things with the list elements, but you can’t put new things in the list. So you’re safe at runtime, because the compiler won’t let you do anything that might be horrible at runtime.

So, this is OK inside takeAnimals():

for(Animal a: animals) {

a.eat();

}But THIS would not compile:

animals.add(new Cat());

You probably remember that when we looked at the sort() method, it used a generic type, but with an unusual format where the type parameter was declared before the return type. It’s just a different way of declaring the type parameter, but the results are the same:

This:

public <T extends Animal> void takeThing(ArrayList<T> list)

Does the same thing as this:

public void takeThing(ArrayList<? extends Animal> list)