Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Bolshevik leader and founder of the Communist Party in Russia, leads the Russian Revolution in Moscow, 1917.

The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany

After World War I, Russia and Germany began a political experiment that ensured the twentieth century would be one of the most violent in world history. As the two most potentially powerful vanquished states of the Great War, Russia and Germany entered a new age of autocracy using lessons learned from World War I. Russia became the soviet Union and Germany fell under the control of the dictator Adolf Hitler.

By the 1930s, both states had totalitarian regimes that produced a new political reality through the sheer willpower of a people transfixed by dictatorship. Both were hostile to the external world, which they regarded as threatening enough to require maintaining a despotic central government. Both mobilized national politics along military lines based on lessons learned from the war, and each distrusted the other enough to desire its destruction.

At the same time, the victors of World War I had lost faith in themselves as well as in their definition of civilization. Given that Europeans measured reality through human creativity expressed in culture, how could any supposedly rational, modern, and advanced civilization claim to be the pinnacle of human achievement and yet engage in four years of war during which the only species that prospered was the trench rat? since these rats thrived on both fronts by eating the flesh of the dead and dying, what type of animal were the “civilized” humans who had created these battlefields?

How could European nation-states continue to condemn the rest of the world as backward when Western society had used science and technology to kill 10 million young men and had made 20 million vulnerable to the flu? after World War i, the Spanish flu swept the world, killing twice as many people as were destroyed in the Great War due to the weakened condition of those infected. How could the nations of Europe hold their heads high knowing that the deaths of these people had eliminated the very best their culture had to offer the world? What good was the reason that Europeans claimed to have in politics if they allowed such a war to continue despite the unimaginable destruction it produced? Unable to answer these questions, Europeans became badly demoralized.

This demoralization was profound. For the victors, it took the form of international weakness. Britain, France, and the United states had lost faith in their moral codes, and the British and French had also suffered devastating human and material losses. Yet nowhere was demoralization more profoundly felt than among the people of the defeated powers. Their degree of demoralization would have to be very great to allow someone like Adolf Hitler to come to power.

The world was now in transition, as the center of power began to shift away from Europe. New powers, including the United states, the soviet Union, and Japan, emerged to take Europe’s place. European empires everywhere began to show signs of erosion. Europe had not only paid heavily in human life, but it had squandered the wealth its nation-states had accumulated over the course of the nineteenth century. Britain and France had liquidated their combined $28.7 billion that they had loaned to other countries and gone into debt to the United states for some $10 billion in gold. Germany had lost its $6 billion in credit entirely, lost its empire, and was forced by the terms of the peace treaty the Allies drafted in Versailles to pay a war indemnity of $35 billion. While the United States and Japan had become creditor nations, the financial structure of the world was in disarray.

The vast demoralization suffered by the defeated powers of World War I led to a new model of political authority— totalitarianism—that changed the face of world history. Stretching autocratic power to its logical conclusion, totalitarianism intensified and modernized authoritarian rule. Totalitarianism concentrated the instruments of national politics in the hands of a single dictator who sought a self-proclaimed historical destiny based on the unrestrained application of Machiavelli’s notion that the end justifies the means.

Totalitarian states differed in content (the specific political objectives) but not in design. Totalitarian governments were designed to apply the lessons of total war to produce the complete mobilization of a nation during times of peace. The actual aims of a particular totalitarian power depended on the cultural circumstances of the nation utilizing it. In one state, the aims might reflect the philosophy of Karl Marx adjusted to local cultural needs. In another, it might reflect the racist intuitions of a national Fascist leader who rose to power by offering a response to the defeat in World War I, postwar demoralization, and dire economic straits. In both cases, the form and structure of the totalitarian state blended together to generate the most intense concentration of authoritarian rule to date.

In the aftermath of World War I, the Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany (which later absorbed Austria) each became fully developed totalitarian states. They were the first to establish the political forms that gave their leaders total command over their societies. To achieve this control, these states integrated four key features of power: first, each developed a single-party state; then, each introduced absolute control over mass communications; next, each extended this control to all social, economic, or political form of assembly; and finally, each refused to allow any legal restraints on the will of its leader.

Totalitarianism concentrated the instruments of national politics in the hands of a single dictator who sought a self-proclaimed historical destiny based on the unrestrained application of Machiavelli’s notion that the end justifies the means.

All four of these features of totalitarianism revealed that the new autocratic state had taken on a war footing, justifying this move in peacetime by citing its revolutionary authority. But whether these despotic governments were radical or conservative, they all used the total war model for mobilizing the home front.

The style of totalitarianism that emerged in the Soviet Union was an expression of its unique revolution under an all-powerful leader, Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924). Lenin required absolute control over all socioeconomic conditions in what had been czarist Russia in order to create a Marxist society in a country not yet ready for communism. Because of the steps he took to win the Russian Revolution (see below for details) and to shape the future society he desired, Lenin found himself forced to create the first totalitarian regime.

Lenin had taken the first step toward achieving his Marxist goals, however, long before the Russian Revolution, when he defined the revolutionary function of a political party in 1903. During a meeting of the Russian Social Democratic Party held in London, Lenin set the standards of political conduct needed to establish totalitarian rule. During this party congress, Lenin demanded a strongly centralized party; he wanted to concentrate absolute authority at the top of the party structure. From this position, he wished to create a “party line” for all other members to obey. issuing from a central revolutionary committee at the top, the party line would then pass down the ranks to the base of the political organization. Through this vertical power scheme, Lenin hoped to consolidate a single professional, revolutionary will that would shape all political action.

Given the small proletariat available in Russia in 1900, this country seemed the least likely place in Europe for a communist revolution to occur. Only 7.5 percent of the total population had become proletarians. Sixty-four percent of Russia’s population remained peasants.

Lenin’s new design for this political party reflected the conditions facing him as a Marxist hoping to create a communist society in a society that had not yet achieved the capitalist phase of history. Lenin wanted to avoid what Karl Marx condemned as voluntarism, which meant launching a revolution prematurely, before a state’s industrial economy was fully developed. according to Marx, such an effort not only would fail but would also cause the voluntarist revolutionary to produce capitalism—the very thing that Lenin hoped to destroy.

Russian Marxists knew that capitalism and the industrial revolution were necessary to create the vast working class needed for communism. An industrial revolution transformed society by relocating the majority of people to cities, where they could acquire literacy, the ability to calculate, and the capacity to engage in critical thinking, which would make them politically active. The industrial proletariat was essential to Marxism because the working class alone had the correct social experiences and mental skills needed to understand the “scientific” truths of communism.

In other words, proletarians alone could engage in the political thinking needed to mobilize the masses of oppressed labor whose energy (according to Marx) had created all the wealth of the world, but who were historically mired in poverty. They alone could generate the numbers needed for a swift victory in a Marxist revolution, a brief dictatorship of the proletariat, and the necessary transition period to the stateless and classless society described in the Marxist vision. Yet, not enough of these precious industrial workers existed in Russia to achieve the future that Marx had predicted. Like all other Russian Marxists, Lenin found himself forced to develop a political strategy that would allow him to avoid voluntarism, complete the evolution of capitalism without becoming a capitalist himself, and establish a Marxist reality.

Given the small proletariat available in Russia in 1900, this country seemed the least likely place in Europe for a communist revolution to occur. Only 7.5 percent of the total population had become proletarians. Sixty-four percent of Russia’s population remained peasants. The likelihood of Marxism taking root in this social environment was very remote. Marx himself despised peasants for their lack of literacy and critical thinking skills, which made them subject to superstitious beliefs (religion) and political manipulation. in fact, he had described peasants as politically untrustworthy. Their praxis, or work experience, derived from both rural and traditional sources. As a result, peasants were illiterate, bound by tradition, and dependent on religion. in Marx’s view, peasants represented a major threat to any true radical movement, especially a communist revolution, even though they might happily participate in spontaneous revolts against their immediate circumstances.

Peasants were dangerous because they were fundamentally conservative and had been used as counterrevolutionaries in nineteenth-century Europe. Peasants had fought the Radical Republicans in the second Phase of the French Revolution (1792–1795) and had aided in the defeat of spontaneous revolutions in Europe during the 1820s and 1830s and in 1848. Any political leader who appealed to the peasants’ appetite for bread and land could easily manipulate them. Unlike Marx, Lenin saw peasants as a revolutionary tool, but clearly could not trust peasants to produce a Marxist future of their own free will.

Because any Russian communist thoroughly trained in Marx’s political theory believed that the only acceptable socioeconomic system was communism, he or she could not tolerate having to fight a revolution to establish capitalism first. Yet, if he or she did not, then the would-be revolutionaries would be surrounded by peasants, not the proletariat. Only a capitalist experience could convert peasants into working-class people while focusing their political rage on the owners of stock. Without this necessary step of social transformation, the Marxist revolutionary would become a voluntarist and as such, the source of capitalist change and the target of peasant rage. Ironically, such a Marxist would then himself be overthrown by other Marxists who had waited until the right moment to rebel.

As a careful reader of Karl Marx, Lenin had discovered that his political mentor spoke with two voices. The first developed a theoretical critique of private property based on the mode of production that outlined all human history. The second analyzed society from a socioeconomic perspective. The first voice spoke of class struggle in terms of the great revolutions of world history, while the second tended to dissolve class as a social entity, that is, a collection of social groups with widely differing immediate political goals. For example, industrial workers could be drawn into unions or form revolutionary parties; the former would preserve capitalism, and the latter would create communism. Each voice functioned in a different way and did not share a common intellectual space.

As a theorist, Marx argued that each class, produced by shared work experiences that generated a collective consciousness, was a cohesive social group hostile toward the other social classes in society. As a historian, Marx demonstrated that classes were not actually as cohesive as his theory suggested. His analysis of the French Revolution, the Sepoy Rebellion, and the Revolutions of 1848 identified individuals whose moral consciousness might elevate them above their personal socioeconomic experiences and allow them to escape their class consciousness. Marx’s historical commentaries revealed that specific individuals were capable of free thought independent of their social existence. These people Marx called “the educators.”

Noting that all revolutions in modern history had been instigated by the educators, not the oppressed, Marx argued that these so-called “chance personalities” were essential to his vision of history. Marx himself fit into this category. He came from a professional family at the heart of the bourgeoisie (the capitalist middle class). Marx’s father was a lawyer, and he himself was a historian and newspaper reporter. Yet Karl Marx chose to abandon his bourgeois roots and take up leadership of the proletariat because he had a unique personality and a strong sense of indignation at what he called “humanity’s long history of exploitation.” His moral detachment from the bourgeoisie allowed him to attempt to educate the proletariat.

Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Bolshevik leader and founder of the Communist Party in Russia, leads the Russian Revolution in Moscow, 1917.

Like Marx, Vladimir Lenin also came from the bourgeoisie. His father was an inspector of education for the czar and a member of Russia’s upper-middle class with a bureaucratic rank equal to that of a major general in the military. Like Marx, Lenin rejected his social upbringing and abandoned capitalist values. He accepted Marxism as the one true social science. Lenin joined the cause of the proletariat after the execution of his older brother in 1887 for plotting against the czar. A student demonstrator and an inmate in the czar’s prison system in Siberia, Lenin converted to Marxism in his youth and built his political agenda on Marx’s concept of the educator. A passionate ideologue, he proposed the idea of creating a professional revolutionary party that could function as a corps of educators to oversee and direct the revolution in Russia. Functioning as the vanguard to this Marxist revolution, the educators would convert Russian peasants to Marxism and prepare them for revolutionary change. Made up of a tiny minority of radicals in the international Marxist movement, Lenin’s party, the Bolsheviks (Russian for “the majority”)—so-called because they had won the majority vote at the party congress in 1903—accepted the discipline of a professional revolutionary cadre.

Lenin developed his party of educators into a corps of 6,000 professionals by 1917. Using these people as skilled agitators, he hoped to transform the destiny of Europe after capturing power in Russia. In the midst of World War I, with an exhausted Europe seemingly on the verge of collapse, he saw the Russian Revolution begin in March 1917 and sought to build a revolution on the ashes of the czarist regime, hoping it would become a potential political tool for global change. Viewing World War I as a capitalist exercise in profit-seeking, Lenin called total war the final phase of capitalism, the last gasp of an ultimately flawed system that could only end in class and international warfare. His political goal was to gain control of the revolutionary process in Russia and then export it to Europe. Once in power in Europe, Lenin hoped to use the human resources of the industrialized West—the vast pool of angry proletarians—to create a global communist system.

Joined by Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), a Menshevik (one of those who voted against Lenin in 1903), Lenin produced the idea of “minority revolution,” the idea that the educators should capture leadership in the revolutionary drama unfolding in Russia. Drawing on Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution (1905), Lenin argued that once the proletarian struggle began, it had to continue without regard for national boundaries and spread from Russia into Europe. Since Marxism had declared that the state was the instrument of oppression by the ruling class, all nation-states had to be destroyed. Thus a Marxist revolution in any location on Earth was, in fact, an international movement dedicated to liberating the entire world from the evils of private property. Melding the concepts of permanent revolution and minority revolutionary theory allowed Lenin and Trotsky to seize the leadership of the revolutionary process and convert Russia into a political platform for world change.

Marxist and Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky addresses the Red Guard, which consisted of armed workers as well as defectors and mutineers (decommissioned soldiers). The Red Guard aided in instigating, supporting, and defending communist revolutions.

Lenin initiated the first phase of the Russian Revolution in November 1917. He captured power and launched “war communism” (i.e., class warfare in Europe and Russia). Declaring peace with Germany in 1918, Lenin gave away most of European Russia to the Germans, believing he would recover these losses later when he captured all of Europe. Having a mere 6,000 original Bolsheviks to work with, he faced an enormous task. He had to recruit Mensheviks, socialists, anarchists, and other radicals to carry out his political plans. He also needed this growing political party to implement an expanding revolutionary process. Yet each new recruit to his party came from sources he generally considered to be undisciplined and untrustworthy.

Growing rapidly from 6,000 to 200,000 thanks to these unreliable people, Lenin’s party tried to control the historical destiny of 170 million Russians. To ensure that the revolution followed the proper course, he had to guarantee that only his original 6,000 educators had a legitimate political voice. He therefore had to police his own party, divide the inner circle from the new recruits, and see to it that party discipline was rigidly enforced everywhere. This process entailed excluding all opinions other than the Bolshevist from the political dialogue.

Lenin imposed a military discipline on the members of his vastly expanded party. Commands came from the central revolutionary committee at the top. Freedom of speech existed only in this central committee, while everyone else had to obey orders. Even still, Lenin saw the need to develop a secret police force to watch the conduct of each party member as well as that of the general population.

As the revolutionary struggle unfolded, war communism created pure class conflict in Russia: Lenin had established Marx’s dictatorship of the proletariat. According to Marx, such a dictatorship was necessary because only the working class had the correct social consciousness needed to make the correct social decisions; only the proletarians could be trusted to implement Marxist policy. All other classes were suspect and had to be eventually eradicated. Yet if the proletariat did not constitute the vast majority of the people (as in Russia), this stage of dictatorship could go on indefinitely. Would not the dictatorship then become a state, function as the instrument of a new class, and thus violate Marx’s vision of a classless and stateless society? These were Lenin’s problems.

Promising the peasants “land, peace, and bread” to win their loyalty, Lenin gave this 64 percent of his population what they craved: their own farms, carved out of the vast supply of land taken from the mirs and aristocracy in the revolution. Acting expediently to meet immediate needs, Lenin gained sufficient popular support to retain power while World War I played out in Europe. Organizing the Cheka, or secret police, to suppress any political opposition within or outside his party, Lenin moved toward the day when his revolution could be exported to Europe. Yet, just when that day seemed to dawn in 1919 and 1920, the general European revolution failed to materialize. Now Lenin found his movement trapped within Russia and surrounded by peasants.

European Marxists like Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Leibknecht, and Bela Kun had launched Marxist revolutions that complemented Lenin’s efforts in Russia. Luxemburg and Leibknecht had organized the Spartacist Movement in Germany between November 1918 and January 1919. In January 1919 they attempted to overthrow the new social Democratic government of Germany. But the German army, members of the radical right, and the government of the new Weimar Republic (1919–1933) joined forces to destroy the Spartacists. Communism lost two of its brightest stars when Luxemburg and Leibknecht were summarily executed in January.

Promising the peasants “land, peace, and bread” to win their loyalty, Lenin gave this 64 percent of his population what they craved: their own farms, carved out of the vast supply of land taken from the mirs and aristocracy in the revolution. Acting expediently to meet immediate needs, Lenin gained sufficient popular support to retain power while World War I played out in Europe.

Bela Kun led a Bolshevik-style revolt in Hungary. Captured on the Russian front during World War I, Kun had joined the Bolsheviks during Lenin’s revolution. He was then sent back to Hungary in March 1919 to persuade the Hungarian communists and social Democrats to form a coalition government. Under his dictatorship, Kun set out to spread the revolution throughout Europe. He managed to overrun Slovakia and influence affairs in Bavaria, but his regime collapsed after his defeat by a Romanian army of intervention. Bela Kun himself then fled to Russia, where he met his death during the great purges of the 1930s (see below).

Even though he was absorbed with his own revolution, Lenin hoped to give all possible aid to the leftist-socialist movements in Europe. As part of the overall design of world revolution, the Bolsheviks sent large sums of money to Germany, Sweden, and Italy. These investments, however, accomplished nothing because of the ideological hostility of the victorious Allies to Bolshevism and the anticommunist elites who took political control of the new states created in Central and Eastern Europe out of territories taken from Austria and Russia. While Lenin contemplated launching a military expedition to support Bela Kun, he had to abandon the idea as strategically infeasible when conservative opposition to the Bolsheviks became firmly established in Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and an expanded Romania.

Even though he was absorbed with his own revolution, Lenin hoped to give all possible aid to the leftist-socialist movements in Europe. As part of the overall design of world revolution, the Bolsheviks sent large sums of money to Germany, Sweden, and Italy.

Meanwhile, the majority of European socialists seemed to reject Lenin’s movement and watched as Bolshevik efforts failed wherever they sprang up in Europe. Capitalism did not collapse after World War I as Lenin and Trotsky anticipated. Even when the Russian communist “Red Army” invaded Poland to try to spark revolution in 1920, the Poles defeated this Bolshevik drive. Late in 1920 Lenin confronted a political crisis as Russia was internationally isolated, confining him in a country whose people he did not admire or trust. Now he had to revise his plans to transform Russia into a communist society.

Simultaneously, Lenin faced hostile peasants at home because of a famine. The growing social rage of Russia’s citizens derived from the chaos caused by war and revolution. Industrial production had fallen to 13 percent of the output in 1914. The new Soviet Union was in complete disarray after seven years of inter national and domestic conflict (1914–1921). Some 20 million people suffered near-starvation. To make things worse, Russia began 1921 with no prospect of foreign aid because of the Bolsheviks’ plan to incite communist revolt around the world.

To retain power, Lenin had to rethink his principal political goals. His new objective was to transform Russia into a society suited for Marxist revolution. At the same time, he wanted to maintain an international revolutionary movement. To accomplish both goals he had to avoid becoming the capitalist Marx had forecasted for those who began a communist revolution too soon. All these concerns combined to place a heavy burden upon Lenin.

Abandoning war communism, Lenin launched the second phase of his revolution, the “new economic policy.” Tolerating private property in agriculture, Lenin allowed the peasants to keep their land, produce food, and sell excess grain for a profit. He hoped to tax the surplus to generate revenue to revive industry and supply a growing industrial working class. He also allowed the private management of small firms of twenty or less workers. Yet the state would retain control of heavy industry, transportation, finance, and international commerce.

Simultaneously, Lenin redefined Soviet foreign policy. He proposed a two-track form of international relations characterized by two conflicting styles of diplomacy. While maintaining a Communist International Committee for World Revolution known as the Comintern, Russia also entered an era of “peaceful coexistence” with Europe. Lenin developed this double diplomacy to create normal relations with powerful European nation-states he wished to exploit as a source of foreign aid while pursuing his hidden goal of world revolution.

Such a mixture of peaceful and revolutionary goals required absolute political control. This control had to descend from the top, in line with the Bolshevik variation of Marxist theory. Also, such control would help Russia avoid “neo-capitalism,” an alternative to the fourth, communist productive stage in human history that Marx had defined in his unilinear teleological model of social evolution (see chapter 22). Each step in imposing this new level of control had to be seamless in design.

The goal of world revolution was essential, but it would have to go underground. Until the day when communism actually materialized, a new state apparatus of awesome power had to be constructed in Russia. This state would have to impose the dictatorship of the proletariat upon the people of the emerging Soviet Union until private property collapsed everywhere else in the world. Consequently, Lenin had to launch a revolution of indefinite length that required, paradoxically, a state designed to end all states.

ABANDONED MARXISM

The USSR, and every other state that assumed the communist mantle after the Russian Revolution of 1917, found itself in direct contradiction with Marxism after the initial success in overthrowing the previous regime. All communist states in the twentieth century either partly or completely abandoned Marxism, and they took up a new form of capitalism because the totalitarian states that Lenin and Stalin created failed to achieve the ultimate Marxist goal. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, after the rise of Mikhail S. Gorbachev, saw pragmatic politicians eventually pave the way to a capitalist economy. The appearance of capitalism in those countries that followed in the Soviets’ footsteps, such as China, Cuba, and Vietnam, constitutes one of great ironies of postmodern world history.

The appearance of capitalism in the USSR after 1991 resulted from issues that Marx himself raised in the nineteenth century. Marx had warned his followers against what he called voluntarism. By voluntarism, he meant a revolution that took place before the economic conditions for a true communist revolution existed. The German philosopher claimed that all revolutions throughout world history erupted only when a changing economy created the right socioeconomic conditions to sustain the revolutionary violence appropriate for a given historical period. Marx himself identified five such historical periods, and he spent a lifetime analyzing the economic foundations needed to build the revolutionary condition appropriate to each era.

For Marx, “the means of production” (his term for the economy) generated “class warfare” (his term for social violence). The end product of all class warfare was revolution. A revolution could only take place when the appropriate economic conditions existed to produce an oppressed class and sustain its efforts to throw off the yoke of an older ruling class and take over the reins of power. According to Marx, each stage in human history began with such a revolution, and then economic changes within that stage laid the foundation for the next appropriate productive era. Therefore, no revolution could succeed unless its economic conditions were already in place before the oppressed class rebelled, and no single stage in history could be bypassed.

Marx’s vision of economic change and revolution created a rigid set of rules for historical change. In his writings, he laid out a five-stage process of economic development. The first stage was “primitive communism,” or hunting and gathering; the second, “Oriental slavery,” encompassed the slave-based economies found in Greece and Rome; the third, “feudalism,” referred to the serf-based agrarian system found in medieval Europe; the fourth, “capitalism,” relied on the industrial working class as the source of labor in modern Europe; and the fifth, “communism,” involved these industrial workers rising up and creating the utopian workers’ paradise he predicted. Marx then generalized these stages and tried to fit the rest of the world within them. Also, he argued that as each stage developed, it spawned the class divisions and antagonisms that inspired the next revolution. Each stage, however, had to wait until economic conditions were ripe before a revolution could be launched.

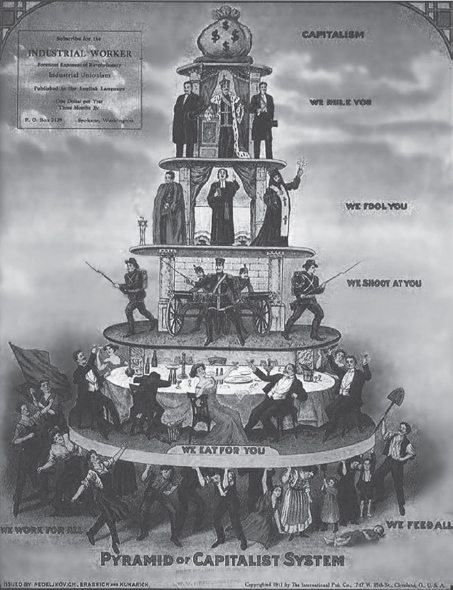

“Pyramid of Capitalist System” IWW cartoon illustrating the hierarchical system of capitalist rule in America with multiple tiers of working class oppression.

Illustration from Cleveland: The International Publishing Co., 1911.

Marx then went on to argue that if a revolutionary leader launched his revolution too soon, one of two fates awaited him: his revolution would either fail from lack of support, or he would produce the stage in the process of historical development that he was trying to skip. For example, if a Marxist wished to launch a communist revolution, he had to wait until capitalism created the correct social conditions needed to mobilize the working class into a revolutionary party. Should this Marxist launch try to launch a communist revolution in a feudal society, he would only generate the capitalist stage, rather than the communist one.

Lenin, Stalin, and later the Chinese communist Mao Zedong (see chapter 30) used Marxism to achieve their revolutionary visions, but all three did so in agrarian countries. Russia and China were peasant societies (i.e., agricultural systems based on peasant farms) when their revolutions erupted. These pre-industrial economies were caught in stages of economic development that Marx himself would have called feudalism. Lenin, Stalin, and Mao orchestrated revolutionary actions that they hoped would allow them to leap from feudalism into communism without waiting for capitalism to create the correct social conditions. But the three leaders, who had hoped to create Marxist paradises, as Marx predicted, were actually perpetrators of what he called voluntarism.

Both the USSR and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) eventually found themselves having to assume a capitalist system in order to save themselves from disintegrating into chaos. In short, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao had successfully established revolutionary regimes, but all three left a legacy of capitalism, the stage they had struggled so dramatically to avoid, in their wake. Thus, in terms of the Marxist vocabulary, the USSR and the PRC under their most radical Marxist leaders fell into a trap that Marx himself warned against.

Thanks to the results of these revolutions, Marx himself would have condemned the three leaders for their actions. He would have stated that their policies failed because they had ignored the historical conditions necessary for a successful communist revolution. He would have condemned their efforts at creating communism before their countries were ready. And he would have declared inappropriate the state-run, planned economies that these leaders established and that proved so destructive to human life. Finally, he would have said that the appearance of capitalism in both countries after the deaths of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao was exactly what his theory predicted.

Responding to all of these pressures, in the midst of the new economic policy period Lenin set up the first totalitarian regime. The Bolshevik party was to be the heart of this new state. Its membership provided the educators Lenin needed to train the different social groups in the Soviet Union to accept a Marxist reality. These educators required access to all the people, so they had to control all forms of the mass media and assembly.

They also had to speak with one voice. To make sure this was the case, the party design had to be vertically articulated and its members had to obey the central leadership without question. Free speech existed only for one elite group: the Politburo (the committee at the apex of political power), which would make all political decisions. In its role as the brain trust of Marxism, the Politburo could not err. This political infallibility required the use of terror as an instrument of revolution. Terror transferred responsibility for errors in judgment and the resulting policy shifts from the Politburo to Soviet society, ensuring that the Bolsheviks could continue to claim omniscience in the revolutionary process. But if the Politburo was infallible in its effort to design the correct revolutionary path to follow, there could be no legal restraint on the imposition of its will on Soviet society. The law itself became a political fiction created by the state for its arbitrary use. Lenin still believed, however, that the Bolshevik state would continue to exist only as long as revolutionary action was necessary.

Lenin completed each of these steps toward totalitarianism just before he suffered the series of strokes that ended his life in 1924. Having survived revolution and restructured Russia into a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Lenin died at exactly the wrong moment. He left an instrument of power that needed his command of theory to achieve his revolutionary goals. Into his place stepped Josef Vissarionovich Stalin (1879–1953).

Stalin rose to power because his colleagues misjudged his appetite for command and his tactical skills at party politics. They had allowed Stalin to take the post of Secretary General of the Communist Party because they felt that this administrative office was appropriate for someone without a significant reputation as an intellectual Marxist. Misjudging Stalin as a dullard and a workhorse, his colleagues allowed him control of the Bolshevik party’s administration. They had no idea that he harbored secret ambitions of his own.

Stalin began his rise to ultimate power by staffing key posts in the vertically articulated party hierarchy with men loyal to him. Gaining control over the party structure in this manner allowed him to swing key votes. In the debate between his colleagues about the next appropriate policy move, Stalin isolated his rivals and excluded or expelled them from the Bolshevik party for failing to follow the party line. As each went, so did his legitimate voice in shaping the vision that would guide the Soviet Union.

Playing one against another, Stalin eliminated Leon Trotsky, Gregori Yevseyevich Zinoviev, Lev Borisovih Kamenev, Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin, and others between 1924 and 1928. Each fell by fighting one another, while Stalin used the party apparatus to back one side or the other and eventually to exclude all their voices. At the same time, he eliminated the right for anyone to have a legitimate political opinion that differed from Stalin’s. By 1936 he felt strong enough to purge the party structure. He executed all his old colleagues who had remained in Russia and had recanted their errors for deviation from the party-line. Finally, in 1940, he killed Trotsky, the only original revolutionary remaining and a rival who had left the Soviet Union in 1929 to oppose Stalin from abroad (for more on Stalin’s purges, see pages 688–90).

At the end of this process, Stalin alone commanded the future of the Soviet Union. Yet his vision was blurred, in the sense that his understanding of Marxism reflected the expediency with which he rose to power. Having no firm anchor in Marxist theory, Stalin’s politics shifted with domestic and international circumstances. His goal was to make the Soviet Union a world-class power. Russia as a platform for worldwide revolutionary change would come second, if at all. For Stalin, success simply meant survival. As international circumstances shifted around him, he adjusted his domestic politics. His sole attempt to establish an intellectual reputation revealed what he wanted to achieve. In 1924 he wrote a pamphlet to proclaim Socialism in One Country, and he adhered to this policy throughout his life.

In short, world revolution gave way to communism in Russia alone, as Stalin set about creating a state capable of defending itself against all external challenges. Yet the absence of a clear international strategy for world Marxism threatened to make the state that Lenin had designed to end all states a permanent political reality. If the Soviet state was permanent, then the Russian revolution would have failed to achieve its Marxist goals. A state, any state, was the instrument of an oppressing class. Paradoxically, Lenin had created the monster he tried to destroy. Moreover, the language of revolution that justified the Bolshevik state required an international revolution. Accordingly, the Soviet Union between World War I and World War II found itself caught in a political contradiction it would never resolve.

The Big Three. Prime Minister Clement R. Attlee, President Harry S. Truman, and Generalissimo Josef Stalin enjoy a brief respite during the last day of the Berlin conference, 08/01/45.

THE VERSAILLES TREATY*

The Versailles Treaty coupled the desire for revenge and national security after four years of total war suffered by France and Britain, with the territorial ambitions of Italy (who had joined the Allies in 1915 for material gain) and the idealistic goals of the United States. Expressed by President Woodrow Wilson in a speech concerning his fourteen points, which he presented to the world in January of 1918, U.S. idealism comprised such principles as: 1) the end to all secret treaties and diplomatic agreements; 2) freedom of the high seas both in wartime and during peace; 3) the removal of barriers and inequities to international trade (a global open door policy); 4) the worldwide reduction of armaments by all powers; 5) colonial readjustments to meet the needs of subject peoples; 6) evacuation of all enemy held territories; 7) the self-determination of ethnic groups in Central and Eastern Europe seeking national identity; and 8) the creation of an international organization to prevent future global wars, the League of Nations. The contradictory nature of these Allied goals, revenge, security, material gain, and idealism, denied the possibility of the victorious powers producing a coherent and effective document in 1919.

Delegates from 27 nations and traditional cultures assembled in Paris in January 1919, but both Russia and Germany had been excluded from the negotiations. Trying to achieve a treaty that Wilson had described as “an open covenant openly arrived at,” soon became impossible given the cross-purposes of everyone present. Instead a more secretive process began where conferences held by the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy, the Big Four, set the tone for the agreement. In these conferences, Wilson’s stern and stubborn idealism ran headlong into British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s fiery and quixotic nature, French Premier George Clemenceau’s determined patriotic cynicism, and Italy’s Premier Vittorio Orlando’s obstinate insistence that the Italians receive territorial concessions to compensate for the cost of the war. What emerged was a document that no one truly liked.

With regard to European security, the Allies designed the treaty to provide protection against any future German aggression. On this subject, Clemenceau refused to yield. He hoped to reduce Germany to a size smaller than France, eliminate the German capacity to initiate conflict, and impose the cost of the war on this vanquished nation. Partially successful, Clemenceau gained control of Germany’s Saar coal mines for fifteen years, established a demilitarized zone in the Rhineland (German territory west of the Rhine), recovered Alsace-Lorraine (lost to Bismarck in the Franco-Prussian War), and was to receive 70 percent of some 19 billion gold marks to compensate France for war damages. Also to protect France’s future, Clemenceau received the promise of defensive alliances with Britain and the United States against any further German military resurgence.

For the Germans, they lost all their colonial holdings, which were turned over to the League of Nations for administration as mandate lands. The Germans also lost their fleet; the treaty reduced their army to 100,000 professional soldiers; and Germany could not have any military aircraft. Furthermore, the treaty explicitly prevented the Germans from manufacturing heavy artillery, building future capital ships, refining any form of aviation, or developing a submarine fleet. Hence Wilson’s universal disarmament had been applied to one country only—a vanquished Germany—while the rest of the world continued to pursue military power. For the specific purpose of imposing an unspecified amount of money on Germany to pay for all war damages (an amount later determined by an indemnity commission to be 132 billion gold marks or 35 billion dollars), the German people had to accept full responsibility for causing the war. This clause of the Versailles Treaty explicitly imposed “guilt” for World War I on the Germans so that they would be held liable. Hence, Germany lost all its gold reserves, control of its natural resources, and had to surrender its merchant marine as partial payment for the war.

In Eastern Europe, the Allies set up a buffer zone against Bolshevism in Russia. Like Germany, Russia had not been invited to Versailles to participate in the peace process. The new regime in the old czarist territories was a pariah state that the Allies wanted to quarantine. A new series of nations run by conservative elites and supported by the Allies, formed what the French called a “cordon sanitaire” (sanitary belt) to prevent the westward spread of the communist infection. Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia made up the new nations in this buffer zone. Romania doubled in size at the expense of Austria-Hungary. Austria and Hungary separated into two new states. The Ottoman Empire disappeared to create an enlarged Greece, the new state of Turkey, and numerous mandated territories that would eventually lead to a redefinition of the Middle East.

Outside of Europe, Wilson’s promise of colonial adjustments to meet the needs of subject peoples opened up a discussion on the topic of empires and their consequences. The complexity of this issue, plus the principle of self-determination offered to the ethnic groups in Europe as a justification to form new nations, proved too much for the delegates at Versailles to resolve. The ambitions of peoples trapped in colonies, protectorates, and spheres of influence to seek independence from European imperial controls proved too complex for the treaty process, or the League of Nations after 1920. Hence decolonization and nation formation began outside of Europe, and the decisions made at Versailles, that revealed the diverse forces released by World War I.

As for the United States, Congress never ratified the Treaty of Versailles. A wave of isolationism and nostalgia for the days before the war swept through the country. Also Wilson’s personal negotiations of the treaty without a bipartisan support team made the document suspect to Republicans back home. The numerous compromises Wilson had to make in Europe made him unbinding in his approach to ratification. To further complicate matters, as pressure mounted due to the political process of ratification, Wilson was incapacitated by a stroke. This gave the Senate a free hand to repudiate his work. Hence the United States did not join the League of Nations or honor Wilson’s promise of a defensive alliance with France against a resurgent Germany. Thus, the League was nearly stillborn without U.S. or Soviet participation, while the Versailles Treaty had promised solutions to far more problems then it was capable of addressing. As a result, the Allies won the war but lost the peace.

* Palmer, R. R., and Joel Colton, A History of the Modern World, 5th ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978), 681–89.

While Stalin fought to consolidate his hold on the Soviet Union, another of the defeated powers of World War I also adopted the totalitarian form of governance. Germany, however, fell to a revolution from the right rather than from the left. Prior to this fall, a crestfallen and demoralized German people had struggled for fourteen years to maintain a democracy, the so-called Weimar Republic (1919–1933).

Democracy, however, did not sit well with an autocratic nation-state like Germany. Shocked by their defeat, certain that they should have won, and eager for revenge, the Germans could not accept the outcome of World War I. Forced to accept the Weimar Republic by the Allies, the people of the kaiser’s Second Reich (the state created by Bismarck) had little patience with liberalism and admired only strong, cunning men like Frederick the Great, Bismarck himself, and General Field Marshal Count Helmuth von Moltke, the military architect of the wars of 1864, 1866, and 1870–1871. These were men who had maintained that Germany’s political destiny required “blood and iron.” Such men mocked the liberal tradition of Germany, which had won nothing but failure in the past, as all of the defeated liberal revolutions of the 1820s and the 1830s and 1848 demonstrated.

Suffering amid the collapse brought on by defeat in the Great War, most Germans could not understand why their country had to surrender in November 1918 when their army still held enemy territory. They did not know that Kaiser Wilhelm II had been persuaded to abdicate by his generals, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich von Ludendorff, for the good of the nation, because his armies would not and could not continue to fight. Unaware of this fact, the Germans watched a new democratic regime take the kaiser’s place and accept a humiliating surrender on terms dictated by the Allies. Then they saw this same Weimar government sign the Versailles Treaty, in which the Allies forced Germany to accept an impossibly high war indemnity, blame for the disastrous war itself, and the reduction of German military power to utter impotence (see insert). In the minds of many Germans, this “stab in the back” by the democratic forces of Germany was just one more instance of the weakness and disaster that democrats had always brought to Germany in the past.

Next the Germans experienced a sequence of economic catastrophes caused by the Versailles Treaty and the peace terms dictated by the Allies. The German currency, the mark, plunged from four per U.S. dollar in 1914 to 4 billion per dollar in 1923; runaway inflation, caused by the war indemnity imposed by the Versailles Treaty, wiped out the savings of the German middle class. Recovery required Weimar Germany to tie its financial future to the United States through two lending programs called the Dawes (1924) and Young (1929) plans. The stock market collapse of October 1929 (see chapter 30 for details) and the subsequent Great Depression brought economic chaos to Germany. From the German point of view, the democrats of the Weimar Republic, working in conjunction with the democrats of the United States, had exposed Germany to fiscal crisis.

Finally, from the moment it assumed power, the Weimar Republic faced nothing but political conflict at home. The radical left under Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht staged the abortive Spartacist Revolution of 1919 (mentioned above) and paid with their lives by being murdered in captivity. Then two right-wing efforts to overthrow the government followed: a local military revolt called the Kapp Putsch (a putsch is an armed uprising) of 1920, and Adolf Hitler’s “Beer Hall” Putsch of 1923. Both rebellions failed, yet, unlike Luxembourg or Liebknecht, neither Kapp nor Hitler died in custody. In fact, Hitler only received a five-year sentence, served less than a year, and enjoyed enough freedom while in prison to be able to write Mein Kampf (My Struggle), a convoluted mix of racism, nationalism, personal intuition, and distorted theories of history designed to serve as the intellectual basis of his new ideology.

Following Hitler’s jail term, the Weimar enjoyed a brief period of calm, but the Great Depression soon accelerated radical activities and paralyzed the German government. Thus, within fourteen years, 1919–1933, demoralization, indemnity payments, and a general hostility toward democracy in Germany brought the Weimar Republic to its knees. Germans in general blamed the Weimar for virtually all the ills that their country faced after World War I: signing the Versailles Treaty; accepting guilt for the Great War; the runaway inflation of 1923 caused by the burden of indemnity payments; and taking loans from the United States between 1924–1929, which tied Germany’s financial future to American prosperity—a prosperity that suddenly collapsed. With no friends at home or abroad, the Weimar Republic also collapsed. With its demise, Germany fell under the political spell of Adolf Hitler (1889–1945).

Hitler quickly developed a political apparatus like the one in the Soviet Union, establishing a single-party state based on vertically articulated power, absolute control over the media and assembly, and no legal restraint on the national leaders. Yet in contrast to the situation in the Soviet Union, in Germany Hitler’s single-party state implemented a political vision that sprang solely from his personal intuition. Although Hitler concentrated political power in the same fashion as Stalin did in the Soviet Union, Germany’s future emerged from the convoluted imagination of Der Führer (German for “the leader”).

Building on the rage that followed a terrible defeat snatched from the jaws of near victory in 1918, Hitler used German hostility to democracy, the myth of “the stab in the back” (see above), the military impotence imposed by the Versailles Treaty, the financial chaos of inflation and depression, and the demoralization that followed the Great War to develop his program. First, he constructed an elaborate conspiracy theory to explain Germany’s defeat. Then he posited the thesis that the Germans should assign the guilt for their failure on a vague, shadowy domestic figure: the Jewish-democratic-liberal-Marxist traitor who spoke of peace and freedom but really wanted to rob the powerful races of the world of their birthright, a global empire. Never concerned with internal contradictions, Hitler pressed this theory on the Germans until their frustrations through the 1920s and 1930s culminated in their raising him to power. Once in power, he redesigned Germany.

Hitler’s thesis defined war as a natural condition for humanity. Believing that race represented a subdivision of the human species, the German leader argued that each race of humans made war on the others as part of the evolutionary process. In this way, superior races eliminated the inferior ones and refined the entire human species. In his racist teleology, Hitler extrapolated his vision of war from a perversion of Charles Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection (1859).

Hitler built his thesis by misusing the scientific theory of natural selection, mutating it into a misguided sociological idea called Social Darwinism. In fact, Hitler’s entire worldview derived from his transformation of Social Darwinism into a unique vision. To understand this worldview and to see how it shaped Germany’s political future one has to return to the nineteenth century to see how Social Darwinism completely misrepresented Darwin’s principles of evolution (see chapter 22).

As mentioned in chapter 22, natural selection pairs success in the struggle for existence with the frequency of reproduction, for only those individuals who survive to reach sexual maturity and reproduce pass their genes on to the next generation. The frequency of reproduction defines successful individuals in a population and determines the direction of speciation. Since no one could predict the frequency with which each individual would reproduce, natural selection constitutes a nonteleological explanation of evolution. Social Darwinists of the nineteenth century, however, tried to link the general teleology of that era to natural selection by misrepresenting Darwin’s ideas.

Social Darwinists dropped the key concept of reproductive success from Darwin’s theory to focus solely on the struggle for existence. They borrowed an expression coined by Herbert Spencer, “the survival of the fittest,” and converted Darwin’s theory into a tautology (a logical fallacy also called a circular argument). Social Darwinists argued that in the case of human beings, as well as other animals, the fit survive because they are the fittest, and since they are the fittest, they naturally outlive their inferior competitors. Hence, the fittest survive due to their fitness, and their survival defines them as the fittest. Social Darwinists furthermore applied this tautology to the marketplace, arguing that the fittest were the richest individuals and the richest nation-states.

The degree to which they erred can be seen by the fact that Darwin’s theory always measured the fitness of survivors by counting the number of offspring they produced. If any of the survivors had no offspring, these individuals ceased to play a part in natural selection. In this case, even so-called winners were as unfit as those individuals who died before reaching sexual maturity, for they left behind no genetic trace of their existence.

Ironically, in the market economy in which Social Darwinists named the rich as the fittest, these individuals followed David Ricardo’s and Thomas Robert Malthus’s theories of economics. Both had argued that the rich should deliberately reduce the number of offspring they had to ensure their continued wealth. Conversely, both theorists had condemned the poor for perpetuating their own poverty by producing too many babies. But according to Darwin, it was the fecund poor who determined humanity’s biological future as a species through natural selection. Hence, by Darwin’s standards, the Social Darwinists were completely wrong when they named the rich and childless as the fittest and the poor with numerous offspring as unfit.

This gap in logic, however, did not stop Social Darwinists from pressing forward their misunderstanding of natural selection. And this glaring error was evidently too subtle for Adolf Hitler to grasp. He merely adapted Social Darwinism to his brand of racism to explain why war was the natural state of human and international affairs.

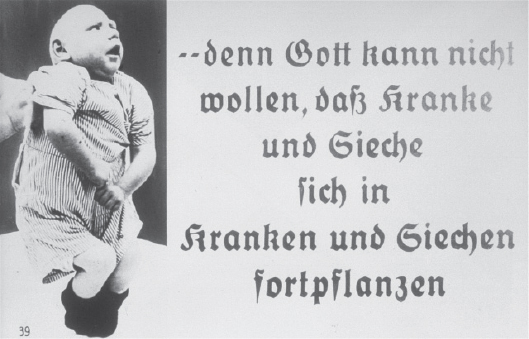

Propaganda slide featuring a disabled infant. The caption reads “…because God cannot want the sick and ailing to reproduce.”

Hitler’s variation on Social Darwinism compressed individuals into races that populated nation-states. According to Hitler, humanity divided itself into nations on the basis of race, with the qualities of each ethnicity creating a unique culture, a Volksgeist (German for “spirit of the people”), and language (see chapter 22). The German dictator then assumed that these races would naturally mobilize their ethnic and cultural resources as nation-states to fight one another. Of all the human races, he argued, the Germans were the fittest; they comprised the highest form of human raw material needed to forge a new social order that would lead the world.

According to Hitler, a race’s success depended on how much land it owned as well as its potential for making future conquests. Great Britain, he posited, comprised the Angles, Saxons, Danes, and Norsemen, each of which was a German tribe, making the British German overall. These were the original peoples of the United Kingdom, and the British Empire that they acquired by conquest proved their superior qualities as Germans. By comparison, Germany was the greatest industrial power of Europe and its people had pure Germanic racial qualities derived from Angles, Saxons, Frisians, Thuringians, Bavarians, and Alemanni. This made this nation Great Britain’s continental cousin, destined to expand east to eradicate the Slavs (an inferior race).

Yet, according to Hitler, both Britain and Germany faced a conspiracy of inferior people whose survival depended on peace. These people had no land and could only survive as parasites among superior peoples. These inferior peoples attempted to frustrate the natural struggle for survival between races, tried to dilute their inferiority to superior people through intermarriage, and sought to erode the superior race’s potential for world leadership. These inferior people had to be unmasked and eliminated.

The facial features of a young German are measured during a racial examination at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology.

With this vision in mind, Hitler turned his attention to the Versailles Treaty that ended World War I in 1919. For the dictator, Germany’s defeat could not have resulted from its weakness. Instead, the nation had to have been “stabbed in the back.” As mentioned above, while the German army was still on foreign soil, the General Staff informed the Kaiser that defeat was at hand but deliberately kept the decision to concede secret so that the German public did not learn of the impending military collapse until it occurred. This defeat, coupled with the food riots at home, spurred an internal disintegration that many Germans were convinced had been caused by a conspiracy led by civilian traitors. Yet who were these civilians? What was their motive? How could Germany’s defeat profit anybody living within the Reich’s borders?

Many Germans agreed with Hitler that the war had been lost because of a domestic conspiracy rather than military failure. They listened to Hitler when he argued that the victors were democratic states—the United States, Britain, France, and Italy—that had imposed a peace treaty on Germany designed to ensure its perpetual weakness. Hitler held that democracy itself resided at the heart of an international conspiracy against the German race. He believed that inferior races had created democracy to spread peace around the world in order to ensure their own survival. In Hitler’s eyes democracy was inherently destructive to the German people, which, in turn, made it destructive to humanity as well.

The mixture of races allowed by democracy through the maintenance of peace confirmed Hitler’s suspicions. From his perspective, democracy could only be the brainchild of those races that could not survive any other way but through acts of miscegenation (interbreeding). Hitler placed the Jews at the heart of this democratic conspiracy. The German dictator’s hatred of Jews ran very deep, and he blamed them for personal as well as international misfortunes. He saw them as the authors of both democracy and socialism, placed them at the forefront of international capitalism, and even made them the creators of communism. This all-pervasive anti-Semitism shaped Hitler’s conspiracy theory into a massive racial plot hatched by inferior peoples to bring down all the superior ones.

Hitler believed that Jews had succeeded thus far because no one had unmasked their sinister plans. According to the German dictator, Jews had carefully masked their “malignant plot” against superior races behind the trappings of universal peace and a humanitarian language that fostered the democratic state. Jews had been leading European proponents of peace and freedom through the intellectual pursuits that produced great works of art, music, literature, philosophy, and science, which in turn supported democratic principles.

At the same time, in Hitler’s vision the Jews made up the leading capitalists of the world. Yet Karl Marx, half Jewish by birth, was the creator of Marxism and the inspiration behind the Soviet Union, the world’s first communist nation. The German leader believed that as capitalists, Jews managed world finance; yet, as communists they also led the revolution against private property and capitalism. He claimed that as leaders of both movements, Jews had to take responsibility for most international conflict.

Jews had devised this state of international warfare, Hitler argued, in order to get superior peoples to fight among themselves; he never bothered to explain how a supposedly inferior people could consistently fool superior people. Despite their inferiority, he claimed that Jews had successfully conspired to pit the superior mass of humanity in a constant struggle among themselves that weakened those races with the greatest potential. Only in this way, Hitler felt, could the Jewish people, without a homeland of their own, have found the geopolitical space to live in the territory of other races.

In Hitler’s mind, the terms laid down by the Allies in the Versailles Treaty proved the existence of this plot. Called the Diktat (German for an imposed, harsh settlement) by Germans because the victors had excluded German diplomats from the peace process, the Versailles Treaty became a symbol of the international betrayal of Germany. In Germany’s view, the victors had broken a sacred trust by denying a defeated power the right to participate in shaping the future peace for the first time in European diplomatic history. Furthermore, the Versailles Treaty transformed Germany, a once great nation, into a weak one.

Building on the rage generated by the Diktat, Hitler developed his political program. According to Hitler, the Versailles Treaty symbolized the way the Jewish-democratic conspiracy worked. This “a stab in the back” could only have occurred if German civilians were secretly working for the democratic victors. Then, the treaty imposed a financial burden on Germany that only international bankers could have devised. Next, the treaty reduced the German army to a mere 100,000 men, eliminated German aviation, and confined the German navy to a fleet of tiny surface vessels. The treaty required that Germany work for international peace and forced it to accept a new democracy that would enforce the restrictions of the Diktat on the German people.

Hitler reasoned that Germany had to break the Versailles Treaty, recover its military spirit, and conquer those inferior races that had tried to deny the Germans their rightful living space (Lebensraum in German). Rousing nationalist passions among those Germans who wanted to right the wrong of 1918, Hitler hammered away at their domestic rage. He repeated endlessly the same simple message that Germany had been betrayed by inferior peoples living within its own borders. A combination of the Great Depression, national demoralization, and domestic rage fuelled Hitler’s political career, bringing him to power in 1933.

His solution to the international conspiracy against Germany was to start a war that would reflect his vision of race and guide the superior peoples of the world to their destiny, thereby respecting the “natural” process of survival of the fittest as expressed in his understanding of Social Darwinism. Integral to his vision was the eradication of the Jewish people. Hitler’s war on the Jews aimed to exterminate them, seize their property, and destroy every vestige of their memory (for more on the Holocaust, see pages 687–88). He would then conquer those peoples who had fallen most deeply under the Jews’ spell. These second-tier victims were races without German traits in their language, culture, or heritage. Such races, which would pose the greatest threat to a world led by the Germans, were an inferior people known as the Slavic races, the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Russians, Ukrainians, etc.

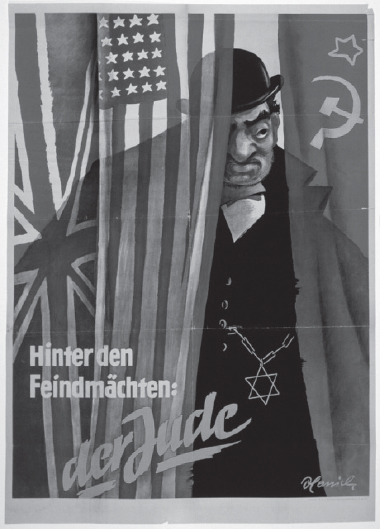

“Behind the enemy powers: the Jews” Nazi propaganda often portrayed Jews as conspiring to provoke war. Here, a stereotyped Jew plots to control the Allied powers, represented by the British, American, and Soviet flags.

A highly stylized portrait of the dictator Adolf Hitler and a good example of Nazi propaganda.

Devising a foreign and domestic policy designed to implement his distorted vision, Hitler set out to reassemble the German people into one nation, one he planned to place on an equal footing with Great Britain, the “other Germany.” He planned to violate the Versailles Treaty progressively, reversing its restrictions one by one at a pace that allowed Germany to regain its strength before launching an attack. He sensed correctly that the victors of the West—themselves exhausted from World War I and having retreated into semi-isolationism—would permit him the time he needed to prepare. First he recovered the military forces and territories taken from Germany in the war, except for Alsace-Lorraine, which remained under France’s control. Then he threw off the financial burdens of the treaty rearmed the German nation, and prepared for his projected invasion of the east.

In October 1933, he withdrew Germany from the League of Nations, an international organization conceived by Woodrow Wilson and designed to settle disputes, part of the Versailles treaty that had been forced on Germany. In June 1934, he eliminated potential rivals in his own party while eradicating democracy in Germany. Throughout 1935, Hitler rearmed his new regime, which he called the Third Reich, with weapons designed to allow a successful invasion of the east. In March 1936, he reoccupied and rearmed the Rhineland despite strict prohibitions against such action by the Versailles Treaty. In March 1938, he effected the Anschluss (union) of Germany and Austria to create the Greater Germany that nineteenth century German nationalists had dreamed about before Bismarck’s Second Reich. In October 1938, Hitler persuaded Britain and France to accept his acquisition of the Sudetenland, the mountainous frontier between Germany and the newly minted nation of Czechoslovakia, promising the British prime minister, Neville chamberlain, that he would not seize Czechoslovakia as well. In March of 1939, he broke that promise, forcing Chamberlain to broadcast on radio a promise of war if Hitler took any further territories. Meanwhile, Stalin, hoping to stop Hitler’s drive east, saw an opportunity in March 1939 to turn the Führer back west; the Soviet and German leaders agreed to a Non-Aggression Pact in August to free Hitler from having to fight a war on two fronts. Then, on September 1, 1939, Hitler attacked Poland to recover the Danzig Corridor (also known as the Polish Corridor) that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Chamberlain finally made good on his promise of war: World War II had started in Europe.

Poised to go east, however, Hitler was shocked by the reaction of the Allies to his failure to keep his promises. He had to make peace with Stalin, leader of an enemy nation he was sworn to destroy, to secure his eastern flank. Hitler then marched his troops west against a people he believed to be part or all German (Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, and Great Britain). He had to do this before he could turn his attention to the living space he coveted, currently occupied by the Slavs whom he intended to eliminate as he created his new German nation. World War II began in Europe by Hitler going in the wrong direction.

Such a misdirection of warfare was symptomatic of Hitler’s military planning. His military goals were never really clear because his thinking was intuitive rather than rational. Hence, he had to make war in the wrong sector of Europe, the Germanic or semi-Germanic west rather than the Slavic east. Despite the lack of clear goals, his army stumbled along from one German success to another because the German military was better prepared to fight the Second World War than were the Allies. Ironically, German victories made Hitler look like a genius to his people, when in fact he had unleashed a war he never fully understood. Nevertheless, once trapped in Hitler’s racial vision of the future, the German people had no choice but to follow him until the end.

Bullock, Alan, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, rev. ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1964).

Fitzpatrick, Sheila, The Russian Revolution, 1917–1932, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984).

Hingley, Ronald, Russia: A Concise History, rev. ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991).

Kershaw, Ian, The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

Lafore, Laurence, The End of Glory: An Interpretation of the Origins of World War II (New York and Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1970).

Lincoln, W. Bruce, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989).

Malia, Martin, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917–1991 (New York: Free Press, 1994).

Mazower, Mark, Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century (New York: Vintage Books, 1991).

Pipes, Richard, The Russian Revolution 1899–1919, 2nd ed. (London: Harvill Press, 1997).

Rauch, Georg von, A History of the Soviet Union, 5th ed. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971).

Toland, John, Adolf Hitler (New York: Ballantine Books, 1976).

Ulam, Adam B., The Bolsheviks (New York: Macmillan, 1965).

Weiss, John, The Fascist Tradition: Radical Right-Wing Extremism in Modern Europe (New York: Harper and Row, 1967).

Wolf, Eric R., Peasant Wars in the Twentieth Century (New York: Harper and Row, 1968).