THE CAMP, THE CANVAS

REWIND COLONY

Sydney was ‘born’ at least three times. The First Fleet sailed into Botany Bay, made contact with the natives, located fresh water, began clearing trees for building and excavated a sawpit for cutting the timber. Stop the cameras! Rewind the film! The action runs backwards: sawpit dismantled, everything packed up, hauled back on board, and the ships retreat from Botany Bay. Begin again: the ships sail into the grander heads of Port Jackson, the natives shout at them from the shores, the scenery takes their breath away. The settlers land, raise the British flag, and begin busily clearing and erecting the tents, which look pretty nestled among the great trees. But now fast-forward three years to 1790. The Camp at Sydney Cove is unplanned and disorderly; it is the convicts’ town and seems out of control, beyond salvage. Good land has been discovered at the head of the harbour, so a new, orderly centre is planned there, at Parramatta. This will be the centre of administration, the hub of an agricultural district. Sydney is merely a ramshackle port town. It will wither away.

It is only with the benefit of hindsight that we know where Sydney’s ‘real’ birthplace was: in the mysterious valley at Warrane. At the time, though, this was by no means clear or inevitable. Arthur Phillip was a stickler for orders and even returned to Botany Bay to make absolutely sure he’d made the right choice in abandoning it as the site of the colony, thereby defying the illustrious Cook and Banks. From the start, too, those self-conscious foundation scenes of Bruegel-esque busyness in the silent forests were upended by the movement of the convicts. Large groups immediately defected and found their way back to Botany Bay, where they begged the people on the French ships to take them away. Soon more than half the convicts had left the Camp at Warrane and some were living in the bush at Botany Bay.1 The colony, and Sydney, would emerge from movement, as well as fixing and building.

‘SAFE FROM ALL THE WINDS THAT BLOW’: SAILING INTO PORT JACKSON2

Port Jackson was another beginning, a more appropriately grand one. Once more the ships sailed along the massive cliffs and headlands of the coast, and again entered the new land through the awesome portal of Sydney Heads. The vision of Sydney Harbour was all the more powerful because of the disappointment of Botany Bay. The famous ‘meadows’ promised by Cook and Banks, seen fresh and green and well watered in autumn, had turned to straw in the blazing heat in the summer of January 1788.3 There had been insufficient water for a thousand-odd invaders, the ships were exposed to the ocean gales and there seemed nowhere large enough or suitable to establish the settlement. So, as we have seen, Phillip sailed the longboats further north, the famous discovery was made, and his famous lines later written: here was a harbour where ‘a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security’. At Warrane, later Sydney Cove, ‘ships can anchor so close to the shore that at small expence quays may be built at which the largest ships may unload’.4

They stood on the decks, entranced as the ships glided past the long, finger-like headlands and secret bays. Surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth tried to find words and images:

. . . the finest terras’s . . . the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any nobleman’s grounds in England cannot excel in beauty those [which] nature now presented to our view. The singing of various birds among the trees, and the flight of the numerous parakeets, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws, made all around appear like an enchantment; the stupendous rocks from the summit of the hills and down to the very waters edge hang’g in a most awful manner from above and form’g the most commodious quays by the water, beggar’d all description.5

There were many such descriptions from the Europeans—lyrical, but also infused with a sense of being on the cusp of grand purpose, of history. They began a long tradition—for the next century at least, new arrivals would feel compelled to write of their first sight of Sydney Harbour.

VISIONS OF NEW SOUTH WALES

The reasons for the founding of the British colony in New South Wales have been hotly debated among historians for some decades now. Traditionalists insist that the primary function was as a ‘dumping ground for convicts’, the unwanted human refuse from England’s overflowing gaols and hulks. The gaols full of prisoners dressed in rags and crawling with vermin were seen as fearful threats to public health, for they were ‘so crouded . . . that the greatest danger is to be apprehended, not only from their Escape, but from infectious diseases which may hourly be expected to break out’.6

Economic historians accorded the colony rather more dignity, arguing that it had strategic purpose as a maritime base for ships ‘following the eastern route into the Pacific Ocean’ and it would establish England’s presence in the Pacific, staking a claim particularly against the imperial ambitions of the French, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch. There were also high hopes of securing the valuable natural resources of Norfolk Island: flax and pine tree spars for the masts, ropes and sails of the British navy.7

Phillip’s Instructions and the unfolding of the settlement itself indicate that the penal motive was the main reason for the project. But as Graham Abbott points out, the term ‘dumping ground’ is entirely inappropriate, since the British government was looking, not for a convenient receptacle for its unwanted population, but ‘for a place where a convict settlement could become self supporting within an acceptably short period’.8 There is also some good evidence for the natural resource motives, and the two did not necessarily contradict one another. Most striking in both cases are the environmental dimensions. On one hand, the plan utilised distance and the new, ‘empty’ lands as a kind of safety valve, dispersing fearful urban contagion. On the other, Botany Bay also promised fair to fulfil the traditional role of colonies: it might provide natural raw material for the Mother Country to convert into manufactured goods to supply the ships of her empire. These two themes—a place where the corrupt and diseased could be sent, and the source of raw materials—were long-lived; they would pervade images and ideas about Sydney and Australia, and its relationship with Britain, well into the twentieth century.

But what kind of colony was this to be? We can read the original vision pretty clearly from the supplies hauled from the holds, lowered into boats, rowed ashore and rolled or dragged into tents and stores. Food and plain-but-serviceable clothing to supply the colonists for two years, cooking pots, simple tools for building and farming, seeds and plants of all kinds, and of course presents to soothe and trade with the natives. Animals and fruit trees were collected en route. The ships were arks, bearing the spores of an agricultural colony to a new land.9

What was not sent is significant too. The colony was not provided with money. No treasury was established in New South Wales, and no thought given to its economic development. The convicts would breed (for both men and women were sent), establish a new society with a subsistence economy, growing food for themselves, their children and their betters, but no more.10 They would have to work hard, and lead simple lives with no need for commerce or consumer goods, or indeed large towns. Governors from Phillip to Macquarie were given urgent and detailed instructions to ‘proceed without delay to the cultivation of the lands’ and on the distribution of land for farms, but they had no instructions at all on town planning or leases—despite repeatedly requesting them.11 They were also expressly forbidden to allow ‘craft to be built for the use of private individ uals’, and ships arriving in Sydney Harbour were not even officially recorded until 1799. The colony was to be kept isolated from the rest of the world, for Phillip was instructed that ‘every sort of intercourse between the intended settlement at Botany Bay . . . and the settlements of our East India Company . . . the coast of China . . . and the islands . . . should be prevented by every possible means’.12 Sydney was not to be a gaol, in the sense of incarcerating people behind walls, but neither was it officially intended to develop as a mercantile and commercial port town. Urban development and urban life were not part of the original vision for Botany Bay.

It was a rather strange, naive vision, perhaps a deliberate anachronism. Eighteenth-century England had already experienced both the rapid swelling of its cities with population increase, dispossessed rural people, and the social and economic upheavals of the commercial and consumer revolutions which predated the Industrial Revolution. The convicts came from the ranks long despised as the ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’. They were the labouring classes at once essential for urban and commercial expansion, yet feared as ‘loose and disorderly people’, the sort who defended their common rights, and had fiercely resisted the massive environmental incursions of the eighteenth century—the land enclosures, the destruction of the forests, the draining of the fens. Since the sixteenth century, in the far-flung colonies and on the oceans, such ‘motley’ peoples had fought state terror with their own, resisted slavery, impressment and tyranny, and taken to swamps and mountains or to piracy to form alternative societies. But they also ‘built the infrastructure of merchant capitalism’, stoked the fires of early industries, kept the ships and wharves, houses and factories running. They were the targets of increasingly savage property laws which hanged thousands and swelled the gaol populations—capital punishment in the service of capital.13

At the same time, there was a striking counter-stream in the cultural profile of the convicts: many of them were urban working people who were participants in that new consumer culture. Employed in the quickening industries and later the factories, they bought up the new cotton prints for their clothes, ceramics for their tables, the buttons, shoe buckles and fashionable hats, cheap books. Store-bought food was replacing homemade and they drank tea, once the sole preserve of the rich, with great gusto. With spreading consumer culture came new behaviours: a sense of social worth which threatened old notions of fixed social relations based on inferiority, deference and submission. Working-class consumers could no longer be so instantly distinguished from their betters by their clothes, food and possessions. For people of rank this was as disturbing as the conspiracies and insurrections of rebels: society was being destabilised.14

In a way the vision for the new colony, vague as it was, expressed utopian ideas of a simpler, rural past which was felt to be fast disappearing beneath the growing commercial towns and their environmental and social problems, their rising populations of criminals and the destitute, the rising spirit of rebellion and resistance and the rising tide of consumer goods. Prosperous, handsome, modernising English cities had no place for the surfeit of dangerous, diseased, desperate working people. Conversely, the cultivation of land had powerful social and political potential, for this was to be no gentle or happy utopia. Hard agricultural toil and simple rural life, ruled with a firm hand, would surely make the convicts honest, make them pliant and deferential and separate them from the unruly pleasures of town life. From the time they boarded the ships, they were to be sober, ‘debarred in all cases . . . the use of spirituous liquors’, except for medicinal purposes. There would be no public houses, no ale houses, no money or goods to steal in Botany Bay. It was too far away from anywhere to rely on imported foods other than official British supplies. The logic was beautifully simple: those who refused to work would starve.15

Perhaps this also explains why the convicts were provided with humble, old-fashioned wooden bowls and platters, and tin plates, instead of the commonly used and reasonably priced modern ceramics. Wooden or treen ware was long out of use in England, as were the pewter and tin vessels which had initially replaced them. These vessels seem to have been regarded with contempt by convicts: they would have been old-fashioned, crude and demeaning. The crosscut pit saws sent out were another anachronism. They were already outdated by 1788, replaced by the circular saw, patented in 1777. The pit saws ensured that timber-working in New South Wales would be a time-consuming, arduous and dirty job.16

The achievement of agricultural subsistence within a deadline of two years was the lynchpin of the plan—it justified the considerable initial expense of the project, and it dominated Phillip’s term as governor.17 It drove the immediate planting of crops, the frenetic exploratory journeys north, south and west in search of arable soil, and the early establishment of public farms, first at Farm Cove, then Parramatta. Unburdening the Mother Country of its financial responsibility for the colony was the leitmotif of Phillip’s despatches home. No wonder the poverty of Sydney’s sandy soils was seen as such a disaster, and so much bemoaned! Sydney had been founded in the ‘wrong’ place, for it soon became clear it could not be the centre of an agricultural district.

WARRANE/SYDNEY COVE: TIME’S OPENING SCENES

At the start, Warrane, with its relatively level, dry, open ground, fresh water and well-spaced trees, seemed environmentally promising. The officers saw the initial work of clearing and setting up tents as the starting point in the historical process of bringing order to the wilderness. Tench had enthused cheerfully about this historic, indeed humanising, mission as the ships left the Cape for the savage shores of Botany Bay:

We weighed anchor and soon left far behind every scene of civilization and humanised manners, to explore a remote and barbarous land: and plant in it those happy arts, which alone constitute the pre-eminence and dignity of other countries.18

When the Fleet reached the ‘longed for’ Botany Bay at last, ‘joy sparkled in every countenance, and congratulations issued from every mouth’. Clearing and building in Warrane was the next inevitable step, and Tench rejoiced in that scene too, as he knew his readers would:

Business now set on every brow, the scene . . . highly picturesque and amusing. In one place, a party cutting down woods; a second setting up a blacksmith’s forge; a third dragging along a load of stones or provisions; here an officer pitching his marquee, with a detachment of troops parading on one side of him, and a cook’s fire blazing up on the other.19

The ‘noise, clamour and confusion’ soon wrought the happy result: ‘As the woods were opened and the ground cleared, the various encampments were extended, and all wore the appearance of regularity’.20 Improving on wild nature, however beautiful and tranquil, was integral to the colonising process; it was both action and proof, and it became the worn groove of environmental thinking. When educated Europeans first looked at the Australian environment, they saw it transformed; they saw the future.

Yet this civilising process, and the philosophical and historical ideas that propelled it, ultimately ran at cross-purposes to the scheme for New South Wales entrusted to Phillip. The isolated agrarian penal settlement may have been the British government’s plan, but it was not the only vision of the new colony. In England, among people who had never seen Sydney Cove, there were rather more glorious prophecies of this colony’s inevitable destiny: it would be a great city, a port of empire.21 A year after the First Fleet landed, and the first reports had arrived back in England, the poet Erasmus Darwin wrote a poem, ‘The Voyage of Hope to Sydney Cove’. It was inspired by the allegorical scenes on commemorative medallions made by Josiah Wedgwood from clay carried in the ships returning from Sydney Cove. These medallions depict ‘Time’s opening scene’ at Sydney Cove: on a rocky eminence above the waters, the allegorical figure of ‘Hope’ meets ‘Peace’, ‘Art’ and ‘Labour’, and together they set both time and history in motion. Hope, Peace and Art are represented by female forms; significantly, Labour is male. His head is slightly bowed, his arm twisted awkwardly behind his back, as though bound.22

The Sydney Cove Medallion, fashioned from Sydney clay and depicting the allegorical figures of Hope, Peace, Art and Labour together setting time and history in motion at Sydney Cove.(Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales)

Darwin’s poem, typical of the neo-classical genre of his day, expanded upon this scene and prophesied a peaceful and joyful transformation of the wild landscape through commerce, agriculture, architecture and public works. The delectable Hope calms the stormy seas and winds, and with Truth on her side and a wave of her ‘snowy hand’, she conjures a golden future, a ‘cultured land’. The broad streets, the ‘circus’ and ‘crescent’, ‘dome-capt towers’ of a fabulous modern city rise, mirage-like, out of the bush. This city’s energy, wealth and security is evident in the piers and quays and their ‘massy structures’, and the ships gliding into the harbour laden with ‘northern’ treasures, consumer goods to exchange for agricultural produce. The ‘high-waving wood’ has been replaced by the waving gold of farmlands, and by fruits from blushing orchards. Yet it is a strangely deserted place: there are no people here, no-one building, farming, working on the ships, or buying and selling goods.

The Voyage of Hope to Sydney Cove

Where Sydney Cove her lucid bosom swells

Courts her young navies, and the storm repels;

High on a rock amid the troubled air

HOPE stood sublime, and waved her golden hair;

Calm’d with her rosy smile the tossing deep,

And with sweet accents charm’d the winds to sleep;

To each wild plain she stretched her snowy hand,

High-waving wood, and sea-encircled strand.

‘Hear me’, she cried, ‘ye rising Realms! record

‘Time’s opening scenes, and Truth’s unerring word.–

‘There shall broad streets their stately walls extend.

‘The circus widen, and the crescent bend;

‘There ray’d from cities o’er the cultured land,

‘Shall bright canals, and solid roads expand.–

‘There the proud arch, Colossus-like, bestride

‘Yon glittering streams, and bound the chasing tide;

‘Embellish’d villas crown the landscape scene,

‘Farms wave with gold, and orchards blush between.–

‘There shall tall spires, and dome-capt towers ascend,

‘And piers and quays their massy structures blend;

‘While with each breeze, approaching vessels glide.

‘And northern treasures dance on every tide!’–

Then ceased the nymph—tumultuous echoes roar,

And JOY’s loud voice was heard from shore to shore –

Her graceful steps descending press’d the plain,

And PEACE, and ART, and LABOUR, join’d her train.23

Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood were the grandfathers of Charles Darwin, who would himself voyage to New South Wales in 1836. The grandson noted with some satisfaction that their prophecies had been fulfilled in the colony—or so it appeared. But his other careful observations were of local ecologies, and they would further inspire his revolutionary theory of evolution, a new way of understanding natural history.24 By contrast, this poem, and the medallions, though shaped from local clay, knew and acknowledged nothing of local ecologies or landscapes, let alone peoples and politics; these were irrelevant. Sydney Cove was not a real place but an abstract space, characterised by what it lacked—culture, civilisation, agriculture, art, commerce. It was merely waiting for the Course of Empire to begin.25 This was the philosophy of colonialism, the theory of empire, and it cast human history in four stages. The lowest and most primitive state, hunting and gathering (clearly the niche of the Abori gines) gave way to pastoralism—the grazing of stock— which was in turn succeeded by a third stage—agricultural settlement, with its golden fields and permanent ‘neat, smiling villages’. The fourth and crowning stage was the development of cities, arts and commerce, signalled by buildings and grand public works. But in Sydney, as we shall see, history was strangely quickened and moved at breakneck speed; all the stages jostled together in the last of lands.26

In this other vision of Sydney and New South Wales, then, there could be no distinctive history. Rather than being a peculiar penal experiment in a particular place, the colony simply fitted into the grand historical narratives of European expansion, by which humankind was thought to ‘progress’ geographically, and through time, from the cradle of Greece and Rome to the ends of the earth.

THE CAMP

In reality, local topography and ecology shaped the rude Camp as much as compass bearings, and those first tents and paths would in turn shape the future town and city. The freshwater stream became the boundary between the two types of authority in early Sydney: civil and military. On the east side, Phillip’s portable canvas house (‘neither wind nor waterproof ’) faced northwards, while to the west were the tents and marquees of Lieutenant Governor Robert Ross, the officers, the marines, and that essential of imperial military diaspora, a ragged parade ground. Some of the convicts were housed in rows of tents behind the governor’s house, men and women separated by the judge’s and parson’s tents, but initially most of them were placed on the west side, north of the military encampment.

By October there were still neat rows of tents running down to the west side of the Tank Stream, though huts seem to have replaced tents on the Rocks and in the east. The first hanging in Australia was from a tree between the men’s and women’s tents—the hanging site probably became the site of the future gaol, where a luxury hotel now stands in George Street. The dead were buried on the slopes south of the military encampment. Early plans of the Camp also show that seeding and breeding were high priorities. Garden grounds were cleared and sown immediately, even though the colonists knew it was the wrong season and were not surprised when the crops failed. Pens were built for the stock—sheep, cattle, hogs and goats—and by April the farm which gave Farm Cove its name had also been established over the eastern headland. By October the farm was simply marked ‘cornfields’ for the grain crops sown there.27

Away from the settlement to the north, on the narrow strip of land at the foot of Tallawolladah—the Rocks on the west side of the cove—the hospital tents were set up to receive the victims of scurvy and ‘true camp dysentery’ which broke out soon after the landing. And further north still, away on the point at Tarra (Tarra means ‘teeth’. Was Sydney Cove a mouth, its shorelines jaws?), Lieutenant William Dawes had a tiny observatory built by his ‘own party of marines’ between February and April 1788. The weather was oppressively hot, the thick brush they had to first clear tore their shoes to pieces. Dawes found it ‘absolutely necessary to give them some rum and water now and then’, as well as some new shoes. ‘In return they wrought almost miraculously’, he reported, ‘as is testified with astonishment by all who have seen what they have done’. And so the authorities discovered a very useful fact: rum was not the harbinger of sloth and dissipation—it was the key to getting things done! The observatory had a conical roof made of whitewashed canvas, with a flap that opened out to the stars. Its clock was set in ‘a very large solid stone’, ticking in one of Sydney Cove’s great rock faces. The first road in the colony was a track from the tents at the main camp, running past the hospital out to what became Dawes Point.28

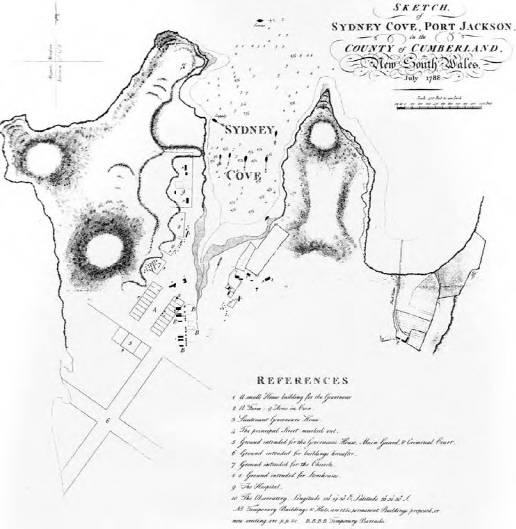

Like many of his rank and education, Phillip was interested in town planning and familiar with the neo-classical notions of the course of empire. By July he had drafted a plan for a future town. The Camp as it stood was clearly considered a temporary arrangement, mere detritus of the rude pioneering stage. Six-month-old Sydney was still a blank canvas, awaiting inscription. Phillip’s town would be named Albion, and it would be an antipodean exercise in ‘baroque principles of town planning’, equal to the ‘extent of empire which demands grandeur of design’. A grand avenue 200 feet wide would run north–east, in a direct line with Sydney Heads, from grand public buildings and a new government house on the brow of the hill, down a gentle slope to a broad piazza at the harbour’s edge.29

But it was a rather odd sort of town. Although there were government stores, there was no provision for merchants, shops or port workers at all. Albion’s shorelines would not be ‘lined with commercial buildings’ but remain public space, controlled by government.30 Like Darwin’s poem, there were no people in it. This was not a plan for a real commercial port town, but a spatial fantasy about control and beauty, an abstract triangulation of authority, elegantly drawn mathematical spaces, and the sea.

It seems Phillip himself didn’t take the plan too seriously. Although the grand avenue was marked out, and the lieutenant governor’s house built, Government House did not migrate, but stayed in the east, where the seat of civil authority thus remained. In fact the east side was considered by the elite as ‘the town’ proper, while the west was ‘clear of the town’.31 First Government House, built of imported and locally burnt bricks, rose in pared-down Palladian style, with a simple gabled bay at the centre. With various additions and extensions, it would house governors for almost six decades. Phillip built a row of handsome brick houses for civil officers, each with a flourishing garden, in what became Bridge Street: the civic side of the town was thus consolidated. New huts for convicts built further south paid no heed to the plan either; as the strange ‘wheel-spoke’ orientation of O’Connell Street and Bligh Street today still shows. Perhaps they were another attempt at planning: an embryonic radial pattern, with Government House at the centre.32

Governor Phillip’s plan for ‘Albion’, July 1788: less a real town than an elegant abstraction of authority, mathematics and the sea. (National Library of Australia)

So Phillip’s Albion never really left paper, while the rough, ordinary buildings and tracks shaped by hands and feet prevailed: it was these pragmatic structures and everyday movements which gave the future city its shape. Emerging roads were mainly set along the north–south axis, echoing the course of the stream, shoreline and the direction of the ridges to the west of the cove. The spaces between the military huts joined the path running north to Dawes Point that became the High Street (later George Street), the spine of the town.

On the western side of the stream, beyond the 200-foot wide corridor of trees which shrouded the Tank Stream, the military encampment also solidified. Huts replaced tents and marquees, and barracks were built by 1792. They had a good view of Sydney Cove and Long Cove (Darling Harbour) but they were ‘directly in the neighbourhood of the ground for burying the dead’, so a new burial ground was opened in an area of clayey ground outside the town to the south. The town’s early dead presumably remained lying close to these barracks. A much more substantial brick complex was erected in the Foveaux and Macquarie periods around what is today Barrack Street and Wynyard Square. These served until 1848, when the soldiers moved out of the town to the Victoria Barracks at Paddington.33

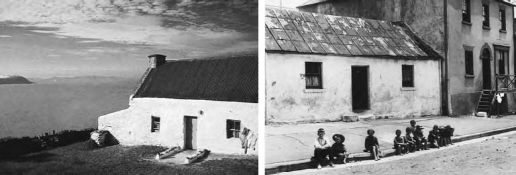

Meanwhile, the convicts in the tents on the western shoreline looked up the wild, broken slopes of Tallawolladah. They called it ‘the Rocks’ and the name stuck. Soon they were creating their own town there, building ‘little edifices’, one- and two-roomed huts of split soft cabbage tree, woven wattles and clay with stubby thatched roofs and no eaves. Central doors hung on leather straps and flanking window-spaces were covered with woven wattle screens. Perhaps the building methods were introduced by rural convicts, for these houses were of ancient lineage: they much resembled the simplest traditional cottages of rural England and Ireland. Such houses were so different from the burgeoning eighteenth-century urban centres that they had become exotic, and romanticised in nostalgic scenes, complete with milkmaids and cows, on mass-produced dinner and tea sets. In Sydney the ‘little huts and cots’ were real, and they gave the Camp a ‘villactick appearance’, their whitewashed walls and orange-brown bricks and tiles ‘quite romantic’, especially scattered along the tree-lined road to the Brickfields.34 As we shall see, newcomers would be amazed and delighted at the ‘English’ appearance of Sydney: it reminded them of a familiar, rural England.

The transmission of vernacular building styles: a traditional Irish rural cottage (left) and a cottage built at the Rocks in about 1810, itself similar in style to the earliest wattle-and-daub houses. (Author’s collection; State Records of New South Wales)

SYDNEY AND PARRAMATTA: TEMPLATE OF ORDER

Looks could be deceiving in so many ways. Like Botany Bay, Warrane proved disappointing as a site for the imagined agricultural colony, and this resulted in yet another settlement—a third founding. Sydney’s sandy soils did in fact support luxurious growths of vines and fruit trees, but this was not enough; it was not ‘real’ agriculture, because wheat and maize failed to thrive. More promising open country, free of ‘underwood, Grass very long’ had been observed upriver by Hunter and Bradley during the survey of the harbour in February 1788.35 By June better soils were found in the shale country at the head of the harbour, and Phillip established a public farm there in 1789. When the crops flourished, he founded ‘the first township’, Rose Hill. Sending stores and provisions to the farm from Sydney would be impractical, he reported, and in any case ‘The Sea-coast does not offer any situation . . . which is calculated for a town whose inhabitants are to be employed in agriculture’. Agriculture, after all, was the raison d’être of the colony, and the destiny of the convicts. The new settlement was later renamed Parramatta, a version of Burramattagal, the name of the Aboriginal owners from whom it had been taken.36

By this time, the Camp at Sydney Cove already seemed beyond official planning and control. Some huts were built under official direction, in orderly rows. These early ‘official’ huts were not originally intended as homes—spaces with emotional and intimate dimensions—but merely basic shelter for a subject workforce called to labour in gangs each day. Occupied collectively, ten to a hut, rather than by individuals, they were meant to impose order and control, not comfort, domesticity and a sense of ownership. Yards were attached—or simply appropriated—to allow convicts to grow their own food, a saving on the stores and a sign of the reforming power of gardening—for convicts and land. This echoed the urban form of preindustrial towns in their early years generally—houses set in yards which were used for work, food production and waste disposal.37

But on the ground, and inside those houses and yards, Sydney developed riotously, largely without order and regimentation. Convicts and soldiers chose sites in their respective zones, built houses and soon regarded them as their own. Chests containing all their possessions stood in the rooms, and they began to furnish the houses with beds, tables and chairs, and even elegant ceramic ornaments and neat china tableware.38 By the 1810s these included blue-and-white bowls, saucers and teacups printed with those nostalgic scenes of lost rural English life, some showing cottages much like those in which their owners lived.39 They cleared irregular patches of land, brought in better soils and planted vegetables and fruit trees. Leases were given to favoured individuals from Phillip’s time on, but the vast majority had no official lease or grant at all: they held the ground by permissive occupancy, by ‘naked possession’.40

This was not simply a matter of architectural chaos and affronted aesthetic sensibilities. It had important political dimensions. If convicts and soldiers lived in their own houses, they possessed private spaces and private lives. If they worked the ground or built structures, their labour, mixed with the earth, gave them property rights. Men and women formed relationships and raised families, and their households became essential to the convict system because they provided board and lodgings for later convict arrivals. Women retreated into their houses and simply refused to come out as ordered, protecting themselves within a mantle of private domestic space. Convicts who were tradesmen and women began to open businesses and work from these houses.

The convict settlers also created social and communal networks, and hence loyalties, with shipmates and workmates, housemates, neighbours and friends from the Old Country.

The buildings and the spaces between them, the marketplace and embryonic squares also allowed the establishment of preindustrial popular culture— the pleasures of drinking, gambling, bare-knuckle fighting and cockfighting, scenes never supposed to exist in Botany Bay. As we will see, these pleasures and pastimes also drew elite patrons, who helped organise them. The King’s Birthday bonfires were another event where plebeians and the higher ranks mingled in the same urban space: Worgan wrote cheerfully that, after their own celebrations, the officers

walked out to visit the Bonfires, The Fuel of One of Which, a number of Convicts had been two Days collecting . . . it was really a noble Sight, it was piled up for several Yards high round a large Tree; where, the Convicts assembled, singing and Huzzaing . . .

It was a rare occasion for shared loyalist sentiment and a still rarer instance of popular support for Phillip, for ‘on the Governor’s Approach, they all drew up on the Opposite Side, and gave three Huzza’s, after this Salutation, A Party of them joined in singing God Save the King’.41

The next King’s Birthday, 4 June 1789, brought the ranks together again. A theatre had been opened in one of the Rocks huts, where the Restoration drama The Recruiting Officer was performed to a highly appreciative audience by convict thespians. Phillip both permitted and attended this performance, yet he made no mention of it in his report to Lord Sydney the following day. A.J. Gray is probably right when he suggests that Phillip most likely considered it wiser not to mention the convicts’ play-acting: he knew it was not quite what the British government had in mind for the convict colony.42 The Reverend Richard Johnson wrote crossly of the urban priorities clearly in evidence in the early Camp:

I am yet obliged to be a field Preacher. No Church is yet begun of, & I am afraid scarcely thought of. Other things seem to be of greater Notice & Concern & most wd rather see a Tavern, a Play House, a Brothel—anything sooner than a place for publick worship.

The theatre disappeared from the official record soon after 1789, although in fact it lasted at least until 1800. 43

So Sydney quickly developed in precisely the opposite way to the original vision for the colony: instead of a closely supervised, harsh, subsistence agricultural settlement, it was a distinctly urban place with considerable freedoms. Yet neither was it the materialisation of Erasmus Darwin’s vision of the grand city with its domes and spires, and the architecture of polite society—or not yet, anyway. Much of the everyday urban landscape—buildings, paths, movements— was shaped by the tastes and habits of the convicts. And their houses had multiple meanings: they could be sites of honest work, families, independence from the stores, and ‘progress’. Governors wrote with some admiration of the domestic achievements of the convict townsfolk. But they were also spaces where people made their own lives, places where stolen goods could be stashed or sold, robberies planned and liquor illegally distilled, places for riot, revelry and conspiracy out of the eye of authority. As for labour, convicts did not even work to regular hours, let alone ‘what would be called a day’s work in England’. They announced that they would ‘sooner perish in the woods than be obliged to work’ and insisted upon the task-work system. This meant that once the daily task was completed, they had free time to earn money, plant their gardens, play or wander as they chose. The authorities were faced with accepting task-work or no work at all.44

Of still more concern was that the military personnel living in houses thought of themselves as ‘independent citizens rather than subordinate soldiers’. Soldiers who lived in huts among convicts made ‘connection with infamous characters there’. These associations were forbidden by their officers to no avail, for ‘living in huts by themselves, it was carried on without their knowledge’. Even when barracks were built, they were insufficient for ‘accommodation and discipline’, and a ‘high brick wall, or an inclosure of strong paling’ would have been necessary to keep them in. Unfortunately, there was not enough labour available to build either.45

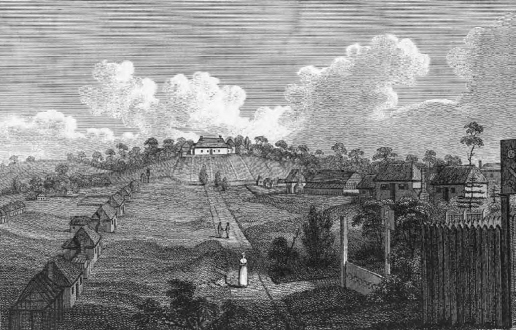

Controlled accommodation and discipline therefore loomed large in Phillip’s startover town at Parramatta. He had learned the lessons of the Camp. As Collins later explained, once convicts got into their own huts, it was too late, for ‘they would be with difficulty removed when wanted; they pleaded the acquirement of comforts, of which in fact it would be painful . . . to deprive them’.46 On this fresh canvas of kinder country Phillip decided there would be no private building or de facto ownership, no crooked rows or hidden places. No unknowable urban spaces, opaque to authorities, refuges for ne’er-do-wells. The government would retain control of land and buildings. Everything would be orderly, open and transparent. The plan laid out a broad street 200 feet wide leading up from the river’s edge to a gentle rise, where Phillip planted his own house, a lathe-and-plaster version of his Sydney residence. The huts for the convicts, each placed at the same setback and distance from one another, lined the avenue below Government House in a long, straight and subordinate procession. Each hut was allotted garden ground as a ‘spur to industry’. The plan also created vistas to imaginary future buildings of civic authority: the town hall, school, church, and a marketplace, which would control buying and selling. Phillip personally supervised the building of his town at Parramatta.47

This plan has been praised as one of ‘grace, balance, charm and utility’ and ‘a fine Renaissance scheme in the best Classical manner’. Some say Phillip was inspired by his visit to Lisbon, and his knowledge of other European towns and cities.48 But to view this plan only through the lens of aesthetics surely misses the point. Phillip needed a town plan which would not only be the centre of an agricultural colony, but would actually work to reinforce his authority over the convicts, and so to fulfil his instructions. And there was another model, much closer to home, which may well have inspired him.

Phillip had farmed his wife’s estate at Lyndhurst in Hampshire before 1769 and then between 1784 and 1786, when he was offered the governorship of the new colony in New South Wales.49 Nearby, in Dorset, was the new village of Milton Abbas, built in 1780 by Lord Dorchester to the design of the famous landscape architect, Capability Brown. Here, a wide street ran straight down a gentle slope, terminating with a view of the vicarage. On either side, arranged with military precision, stood rows of two-storey houses of whitewashed cob and thatch. Lord Dorchester wanted to clear the old village because it interfered with the vistas over his new parkland. The tenants apparently disliked their new houses, and Lord Dorchester, intensely.50

Today Milton Abbas is seen as the quintessential charming Georgian village, steeped in tradition (and hence full of tourists!). But traditional English villages do not look like this at all—they evolved over centuries and typically have an ad hoc, irregular appearance. Milton Abbas was in fact among a number of examples of modern planned housing, part of a larger landscape movement, the ‘emparkment’ of the manor houses. This often involved setting the houses in sweeping, newly created open landscapes of grass and trees—and to achieve this splendid aesthetic, existing villages had to be demolished and relocated. The new villages were usually ‘laid out symmetrically in systematic rows along the roadside’ leading to the gates of the estate, and they formed an impressive visual prelude to the manor house itself. Earlier examples of these ‘adjusted villages’ included Chippenham in Cambridgeshire, New Houghton in Norfolk (‘a number of well-built whitewashed cottages standing either side of the road . . . widely spaced and with particularly large gardens behind’), Harewood in Yorkshire and, most celebrated of all, Nuneham Courtenay in Oxfordshire.51

An anonymous soldier writing home in the early years described Parramatta as Phillip’s ‘country seat’.52 He was right on the mark. Phillip was clearly creating an antipodean version of the modern and fashionable English gentleman’s estate, complete with Government House set in the parklands of the Domain, the neat rows of workers’ huts leading up to the gates, and the farmed fields beyond. The thatched, whitewashed wattle-and-daub huts even looked similar to those of the English model villages.

But, again, there was more to it than aesthetics. This plan was about order and control. Milton Abbas had been much publicised as the most modern, innovative and attractive way to deal with disorderly tenants and their messy, smelly, crooked villages. The model appears to have been adopted in other places around the globe where the control of the workers or slaves was vital. It was a template of order and modernity, at once a material expression of rank and hierarchy, a means of surveillance and control, and pleasing to eyes that sought ‘balance, charm and utility’.53 Interestingly, in both Milton Abbas and Parramatta, the occupants lived communally rather than according to individual family groups—four families to a house in Milton Abbas, ten convicts to a hut in Parramatta. The Parramatta huts, however, were not supposed to be homes: they were intended to be more like barracks, ‘spread over a greater distance’.54

The template: Milton Abbas, Dorset, close to where Arthur Phillip farmed at Lyndhurst.(Photo: G. Karskens, 2002)

Phillip’s startover town in Parramatta: regularity and control were to be imposed through planning and building. (From David Collins, Account of the English Colony)

Watkin Tench was convinced that Parramatta would overtake Sydney as the centre of the colony. Sydney, he wrote dismissively in December 1791, ‘has long been considered only a depot for stores’. The town of only three years was already old and worn out, for it ‘exhibited nothing but a few old scattered huts, and some sterile gardens’. Cultivation of wheat at Farm Cove had been abandoned, public building was at a standstill, and ‘all our strength is transferred to Rose Hill’. When more transport ships arrived, the healthy convicts were sent up to Parramatta, while the sick remained in Sydney.55 By 1792, Phillip was making sure new arrivals did not even set foot in Sydney, so there would be no possibility ‘of any attachment to this part of the colony’. For Sydney, it was said, already ‘possessed . . . all the allurements of a sea port of some standing’. The newly arrived, blissfully unaware of the port’s delights, went cheerfully to Parramatta.56

Sydney prevailed nevertheless. Phillip was still plagued with doubts in 1789, and sensitive to the charge that he had founded the colony in the wrong place. He wrote an account of the difficulties he had faced in selecting the site, and pointed out that ships falling into bad weather could take refuge in Port Jackson, so ‘perhaps it will be found hereafter that the seat of government has not been improperly placed’ after all. Sydney did remain ‘the head-quarters of the colony’ and the governors stayed there, even after Hunter built another elegant Palladian-style Government House on the site of the first house at Parramatta.57 The town at Warrane did not wither, nor did it become a mere government depot or port of refuge alone. Instead it grew rapidly on the rising tide of trade, commerce, shipping and entrepreneurial ambition.

Parramatta, meanwhile, became the centre of Phillip’s vision of rural expansion: clusters of small farms of 30 acres, hacked out of the bush.