Chapter 5

The First Proletarian Barricades: Lyon,

November 1831 and April 1834

‘We have shaken off the yoke of the noble aristocracy only to fall under the domination of the financial aristocracy, we have expelled our parchment tyrants only to fling ourselves into the arms of the millionaire despots. Our lot, accordingly, could not improve; the old ones despised us because we could not cite illustrious ancestors, and the new ones disdain us because we have not been favoured by fortune.’ That is how Auguste Colin, a typographer, expressed himself in 1831, in his newspaper Le Cri du peuple.1

It was in Lyon that the anger of the poor found expression for the first time after the revolution of 1830. This was no accident: Lyon was the largest industrial town in France, with half of its 180,000 inhabitants making their living from silk-weaving. ‘La Fabrique’, as it was known, ‘the manufactory’, was the property of ‘manufacturers’, who made nothing at all but were entrepreneurs or capitalists. They supplied the raw material, that is, silk, to the workshop masters whom they paid by the piece. The master was the owner of the looms. He himself wove on one of these, entrusting the others to journeymen who received an average wage of half the price of the finished item. The majority of the masters, who had only three or four looms, were semi-proletarians, who rapidly united with their journeymen in the conflicts.

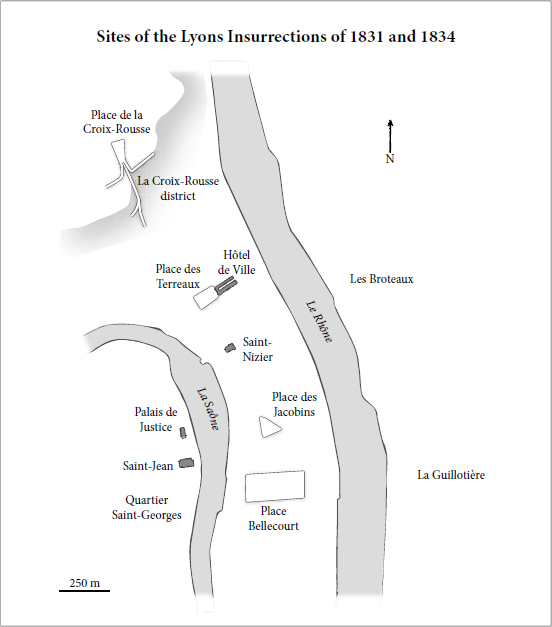

In 1830 the silk workers, known as canuts, still lived in the old Saint-Georges quarter, but increasing numbers of them had moved to the heights of La Croix-Rousse, in housing barracks that had been built specially for them. These weavers worked fifteen or eighteen hours a day for a wretched wage. The prefect wrote to the minister of commerce: ‘There is real suffering among the 60,000 to 80,000 workers. Unless a cruel decision is made to kill them all, we cannot respond to the peaceful expression of their needs by rifle fire.’2

This expression would become less peaceful around the question of the tarif: journeymen and masters tried to impose on the ‘manufacturers a minimum price per piece. The prefect managed to get them to accept the principle, but the ‘manufacturers’, pleading poverty, soon attempted to renege: ‘The great mistake made by the prefect has placed the industrialists in a terrible position,’ they said.3 Their response to strike movements was a lockout, and within a few days thousands of looms ceased to operate for lack of silk and orders.

On Sunday, 20 November 1831, the workshop masters and journeymen, assembled on the place de la Croix-Rousse, decided on a peaceful demonstration throughout the city the next day to demand the tarif – and work. On the morning of the 21st, numerous groups formed on the hilltop. A detachment of National Guard, made up of ‘manufacturers’ and clerks, was welcomed with a hail of stones and had to beat a hasty retreat. The National Guard of La Croix-Rousse (which was at the time a separate commune) had their rifles with them, and the workers also began to arm. The prefect and the general in command of the Lyon National Guard proceeded to La Grand-Côte and tried to parlay, but the overexcited workers surrounded them, scattered their escort with rifle fire, took them prisoner and brought them to the mairie of La Croix-Rousse.

In the course of the day, the army tried to gain a foothold in the plain east of the city, but their cavalry charges came up against barricades constructed in these narrow, crooked and winding streets, from which a rain of stones and tiles fell upon the horses. The soldiers fought only half-heartedly, particularly those of the line, who in some places refused to fire on the workers. In the evening the prefect was released, and the general exchanged for workers who had been taken prisoner. Workers from Les Brotteaux and La Guillotière, who had taken a long detour by the north from the left bank of the Rhône, came to reinforce their comrades of La Croix-Rousse. At nightfall the advantage was on the side of the insurgents.

The next morning, a great crowd assembled to descend into the city, carrying a black flag bearing the famous motto: ‘Live working or die fighting’. The authorities tried to mobilize the National Guard, but the majority of these citizen soldiers refused to enforce order. The drums beating the alarm were attacked, officers were injured or threatened. The insurrection spread to the whole city. In the faubourgs, La Guillotière, Saint-Just, Les Brotteaux, all trades downed tools and the workers joined the insurgents. While the army tried to make its way up to La Croix-Rousse, the streets, squares and quays were covered with barricades. The workers gradually focused on the National Guards of the party of order and the troops in the city centre. From La Guillotière, they crossed the Rhône and occupied the place Bellecour. Those from Les Brotteaux crossed the Pont Morand and reached the vicinity of the Hôtel de Ville, which was encircled on all sides.

At midnight, Roguet, the general in command of the army, decided to abandon the city. The retreat across the barricades was bloody, and the troops had to leave their dead and wounded behind. At three in the morning, the workers entered the Hôtel de Ville. Lyon was in the hands of the insurgents.

Next day a ‘provisional general staff’ was formed at the Hôtel de Ville, grouping the leaders of the insurgent workers with militant republicans. The aim was to replace the traditional authorities with leaders appointed by the workers: ‘Lyon, gloriously liberated by its sons, must have magistrates of its own choice, magistrates whose robes are not soiled with the blood of their brothers!’4 But in the days that followed, dissensions and the lack of a political vision would prevent the consolidation of victory. The government concentrated a veritable army at the city gates, headed by the prince d’Orléans, heir to the throne, and maréchal Soult, the minister of war. The Lyon National Guard was dissolved. The workers let themselves be disarmed, and gradually went back to work. On 3 December the army made its entry into the faubourg of Vaise, the workers’ leaders were arrested, and order reigned in the city.

But not for long. In the following months Lyon was racked by an agitation which now became openly political. The workers founded the Société des Ferrandiniers, a secret association that became a centre of republican propaganda. The cooperative movement and the Saint-Simonians launched a newspaper by share subscription, L’Écho de la Fabrique, which became the organ of the city’s working class. In September 1833 a Lyon section of the Société des Droits de l’Homme was founded, uniting the most combative republican elements: not only workers, but also intellectuals and students, including many followers of Babeuf, who were in touch with their Paris comrades.5

In February 1834, the manufacturers announced a reduction of 25 centimes per aune [approx. 1.37 metres] of plush. The workers immediately reacted – not just those directly affected by this measure, but the whole Fabrique. On 12 February, a meeting of more than 2,000 masters voted for a strike, and some 20,000 looms immediately came to a halt. Other corporations, particularly the typographers, opened a subscription in support of the strikers, but the manufacturers and the prefect held firm, and work resumed at the end of the month.

In the wake of this strike, six leaders were arrested. Their trial was set for 5 April. On that day, the workers descended en masse from La Croix-Rousse and the Saint-Georges quarter to the Palais de Justice, occupying the surroundings and the court itself. The president of the tribunal sent for reinforcements, but when the soldiers appeared the crowd cheered them, and soon troopers and workers were drinking together in the courtyard. The magistrates and court gendarmes escaped through a window.6

On 9 April, the day to which the trial had been postponed, the city was under military occupation: artillery, cavalry and troops of the line were placed at strategic positions, the bridges were blocked, dragoons patrolled the streets. Proclamations were distributed, read out by workers who climbed on bollards, urging the dismissal of Louis-Philippe and calling for insurrection. At the end of the morning, barricades were constructed, first of all around the place Saint-Jean and the court building, then throughout the city. The workers hoped to fraternize with the troops, but the soldiers furiously attacked the hastily constructed barricades, defended by poorly armed men. La Croix-Rousse was transformed into an entrenched camp by a whole network of barricades, but the workers did not manage to descend into the city. Fighting continued throughout the day in the city centre, at Saint-Nizier and Les Cordeliers. In the workers’ quarter of old Lyon, on the right bank of the Saône, all the streets were barricaded. The troops fired on inhabitants who came out of their homes, or at windows if a face appeared. The insurgents were isolated, as the troops had occupied the Rhône bridges, preventing workers from Les Brotteaux and La Guillotière from coming to their aid as in 1831. Despite this they held firm in the face of a hellish fire, and spent the night behind the barricades.

Over the following days the insurgents, conscious of their inferiority in numbers and weapons, waged a guerrilla campaign: they sniped from windows and roofs, withdrawing when troops appeared. As soon as one barricade was taken, another replaced it. But the vice steadily tightened. On 12 April, the fourth day of the insurrection, the troops launched a convergent assault on the centre, where the republicans still held out around the Saint-Nizier and Saint-Bonaventure churches. Insurgents were killed even inside the churches. A priest who witnessed the massacre wrote: ‘Bodies bloody and disfigured by gunfire, the metal of bayonets, broken trunks, altars and tabernacles destroyed, soldiers red with rage (some with drink), fires still burning, a thick smoke throughout the church, a confused and terrible noise of voices, shouts, cries, blasphemies, and blood, blood everywhere!’7 On 15 April, the last shots rang out in La Croix-Rousse.

Throughout these days, troops fired on civilians and slaughtered at random, including women and children. The press of the ‘happy medium’ celebrated the victory and sang the praises of the army. The prefect, Gasparin, was made a peer of France, and the general in command of the troops, Aymar, received the grand cordon of the Légion d’honneur. A special court was formed to judge the hundreds of arrested insurgents. But it was not to be forgotten how in the course of this first proletarian insurrection a small number of poorly armed workers, without a central command, managed with their barricades to keep 8,000 men at bay for a week. ‘This handful of brave men’, wrote one of the canuts, ‘could not have held out for more than twenty-four hours for the sake of any cause other than that of the republic.’8

____________

1Cited in La Parole ouvrière, texts collected and edited by Alain Faure and Jacques Rancière (Paris: La Fabrique, 2007).

2Cited in Jacques Perdu, La Révolte des canuts, 1831–1834 [1931] (Paris: Spartacus, 1974), p. 17.

3Ibid., p. 27.

4Proclamation cited in Fernand Rude, Les Révoltes des canuts (1831–1834) (Paris: La Découverte, 2007), p. 47.

5The Babouvists included Filippo Buonarroti, Charles Teste and Voyet d’Argenson, who spread the ideas of Robespierre and Gracchus Babeuf.

6This and the following day are described in detail in Perdu, La Révolte des canuts, pp. 65–84.

7Ibid., p. 157.

8Cited in Rude, Les Révoltes des canuts, p. 166.