Chapter 6

Barricades in the Age of

Romanticism: June 1832

Chateaubriand and Balzac, Dumas and George Sand, Heine and Victor Hugo: all of these, at one time or another, wrote about the barricades of June 1832, that heroic and desperate battle waged by those who refused to accept the theft of the revolution of 1830.

The republicans were organized: the Société des Amis du Peuple, the Société des Droits de l’Homme, the Société Gauloise and the Réclamants de Juillet grouped the most active of those who were not content with the speeches and protests of the legal opposition. Bonapartists and Legitimists also agitated and took part in the insurrectionary journées.

The anger of the people had been rising since a terrible cholera epidemic in March had killed, at its worst, over a thousand people a day. Many celebrities died, including Cuvier, Champollion and the prime minister himself, Casimir Périer. Eminent physicians such as Magendie, Récamier, Dupuytren, Larrey and Broussais prescribed remedies ranging from ice baths to leeches, opium, blood-letting and various fumigations. But the glaring fact was that the disease struck hardest at the poor: the mortality rate was between eight and nine people per thousand in the elegant quarters, rising to over fifty per thousand ‘in the quarters of the Hôtel de Ville and the Cité, the abodes of penury’.1 Poisoners were rumoured to be spreading death everywhere. The majority of the rich fled the city; the deputies fled, the peers of France fled ‘with a train of doctors and pharmacies’, according to Heine, Paris correspondent of the Augsburger Zeitung. ‘The poor note with discontent that money has become a protection against death.’2

Tension came to a head when the newspapers announced the death of General Lamarque. A nineteen-year-old volunteer at the time of the Revolution, he had fought at Hohenlinden and Wagram as well as in Spain. Banished after the Hundred Days, a patriot and a liberal, in favour of war for the emancipation of peoples, Lamarque was a popular deputy. His family announced that the funeral would take place on 5 June: mourners were to meet at their house on the rue Saint-Honoré, from which the coffin would be taken to the Barrière d’Italie before proceeding to Mont-de-Marsan, the hero’s native town. Republicans took this as the opportunity for an action.

On 5 June it was raining, but from eight in the morning there was a dense crowd around Lamarque’s home. National Guards in uniform were to be seen (artillery in particular, traditionally republican), workers, students and old soldiers. On the place de la Concorde, students from the law and medicine faculties mingled with members of the Société des Amis du Peuple, forming into squadrons and selecting their leaders. The government, for its part, took precautions: carabineers were positioned around the place de la Concorde and troops of the line on the place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville, the place de la Bastille and in the Latin Quarter, while the 6th regiment of dragoons was at the Célestins barracks near the Arsenal – a total of more than 20,000 men.

At eleven o’clock, the door decked with black was opened for the passage of the coffin. This was escorted by Lafayette, Laffitte, the Bonapartist General Clausel and Mauguin, an opposition advocate. The procession advanced via the Madeleine and the boulevards, but on reaching the rue de la Paix, a shout was heard: ‘Around the column with the soldier of Napoleon!’ A right turn, therefore, and the coffin made three rounds of the place Vendôme, where soldiers at the offices of the general staff were obliged to render military honours. The procession then continued along the boulevards:

That immense population, crowding every balcony, filling every window, weighing down every tree, covering every house-top, those flags, Italian, Polish, German, Spanish, recalling to the minds of all who saw them so many tyrannies triumphant, so many insults unavenged; those too manifest preparations for battle; those very precautions of a government whose conscience taught it to see danger even in the passage of a dead man to his last home; the revolutionary hymns rising into the air amidst menacing cries and the mournful roll of the muffled drum, all this disposed the minds of men to an excitement full of peril.3

Just as the coffin reached the place de la Bastille, some sixty students from the Polytechnique came running. They had ignored the order not to leave the school and were ready to join the insurrection. (We may remember the opening words of Stendhal’s second novel: ‘Lucien Leuwen had been expelled from the Polytechnique for having gone for an inappropriate walk, one day when he and all his fellow students were detained: this was the time of one of the famous journées of June, April or February 1832 or 1834.’) The procession followed the boulevard Bourdon, between the Arsenal basin and the grain warehouses, crossed the little bridge at the end of the canal and stopped on the esplanade just before the Pont d’Austerlitz.

A podium had been erected here for valdedictory speeches by Lafayette, Marshal Clausel, and foreign generals. The tail end of the great crowd was still at the Bastille; there was growing restlessness. Suddenly a strange horseman appeared, dressed in black; he passed slowly along the ranks, holding a red flag topped by a Phrygian cap, on which the words could be read: ‘Liberty or death’. This image of 1793 electrified the crowd, but terrified those officiating on the podium: Lafayette hastened off in a fiacre, and General Exelmans, who attempted to object, narrowly escaped being thrown into the canal.

At this point a small detachment of dragoons from the Célestins barracks arrived on the quai Morland.4 The crowd booed them and pelted them with stones, a shot was fired, and the battle began. This time a whole squadron emerged from the barracks, surging through the rue de la Cerisaie and charging the crowd. From the granaries and the Arsenal, the insurgents fired on the dragoons. The colonel’s horse was killed under him. A barricade, the first of the day, was hastily erected on the boulevard Bourdon, and the dragoons had to withdraw into their barracks.

Meanwhile some young people had crossed the Pont d’Austerlitz with the coffin, and reached the Jardin des Plantes. Here a carriage was waiting to take the general to his last resting-place in the Landes, but the insurgents shouted out: ‘To the Panthéon!’ The carabineers who tried to block their path were met by rifle fire. The rioters took possession of the veterans’ barracks, stormed the guard post on the place Maubert, and occupied the entire line of the barriers on the Left Bank.5 On the opposite bank, their advance was equally rapid: the guard posts of the Marais, the mairie of the eighth arrondissement, the post of the Château-d’Eau and the Les Halles quarter were in their hands.6

Paris was already enflamed. The republicans had spread themselves in every direction, running up barricades in the different streets, disarming the military posts, summoning the troops whom they came across to join them, attacking them if they refused, menacing the powder magazines and arsenals, arresting the drummers whom they found beating the roll-call, knocking in the drumheads; a party everywhere small in number, but constantly gaining adherents by their audacious bravery, and everywhere acting in concert. There was never anything comparable with the rapidity of this whole affair: in three hours after the first attack, one half of Paris was in the power of the insurgents.7

By eight in the evening, a barricade had been erected near the little bridge of the Hôtel-Dieu, and the troops retreated along the quai aux Fleurs. The prefecture of police was completely encircled.8

The government was reluctant to get engaged in a battle of streets and alleys, as had been fatal to Marmont’s troops in 1830. Soult, the minister of war, advised a withdrawal to the Champ-de-Mars, but this was opposed by the prefect of police, Gisquet, and the decision was taken to stand and resist. Fresh troops were brought in from the Paris suburbs, as well as artillery.

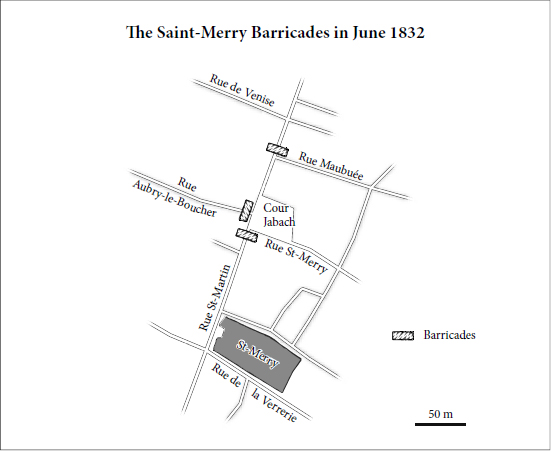

The insurrectionaries established their headquarters close to the Saint-Merry church, in the Saint-Avoye quarter (now Beaubourg). A complex of barricades was constructed on the rue Saint-Martin, by house no. 30. In a letter to his sister, Charles Jeanne, who headed the resistance here, relates:

In a moment, and as if by some enchantment, three strong barricades were raised, the first at the corner of the rue Saint-Merry continued outward and cut the rue Saint-Martin at a right angle; the second, also at a right angle to the former, blocked the rue Aubry-le-Boucher; and finally the third, raised at the corner of the rue Maubuée, brought this latter street within our retrenchments. A house under construction in the rue Aubry-le-Boucher facilitated the execution of our means of defence; wooden scaffolding and rubble, along with paving-stones that were constantly being taken up, were piled up at prodigious speed; a large quantity of rubble, carried on people’s backs in scuttles that were found in the building, was used to fill the gaps and consolidate the work. A very large flour cart that we had overturned and filled with cobbles made up around half of the Saint-Merry barricade. Finally, two hours later, our first two barricades were nearly six feet thick and five feet high, and crenelated all along their length.9

While the people were digging up the paving-stones, the great men of the republican opposition, would-be leaders such as Lafayette, Laffitte, Odilon Barrot and François Arago, were divided among themselves and hesitant to play this bloody game. No name emerged to take the lead in a revolution.

During the night the battle continued to rage, but the insurgents, who were considerably outnumbered, were steadily driven from their positions. The entrenched camp of Saint-Merry, however, held fast. ‘From all sides,’ Jeanne wrote, ‘people brought us packets of powder and some bullets; we had removed the lead from the gutters; but with all that, we had to make bullets and cartridges.’ He put the young people to work and established a dressing station in the house at no. 30:

This first duty accomplished, I kept inside the barricades forty men armed with rifles, as well as the four or five youngsters who would not abandon this post, and I divided up the rest of my brothers in arms, almost all armed with hunting rifles and carbines, in various houses from which they could destroy a large number of our enemies by a crossfire from above, while the barricade fighters stopped them by a sustained and well-supplied fire.

At six in the evening, a column of National Guard arrived from the quays and charged into the rue Saint-Martin: ‘When I stood up [Jeanne had just been wounded], the National Guard were fleeing so hastily, leaving behind their wounded, that I had only time to see to one of them who had fallen dead outright.’ This first attack was scarcely repelled when another column appeared, this time from the top of the rue Saint-Martin:

I placed all my comrades behind the Maubuée barricade, with one knee on the ground, only a few remaining at the crenelation, which was still very low [this barrier was no more than four feet high], so as to encourage the assailants by the seemingly small number of the defenders of our entrenchment. We thus let them advance until they were within pistol range, without replying to the fire that they constantly directed as they marched; but when we all suddenly rose up and gave them such a heated reception, to shouts of ‘Vive la république!’, they were indecisive and stopped: this uncertainty on their part, however, was immediately followed by fresh fire from the barricade and the windows, no less well-aimed than the earlier one, which once again thinned their ranks. Then they were no longer a disciplined body, but a cloud of Cossacks in complete rout.

During this time, a very violent battle was in progress in the passage au Saumon [now rue Bachaumont, between the rue Montmartre and the rue Montorgueil]. A barricade erected at the entrance to the passage long held out, but at four in the morning the last insurgents were massacred. The barricade on the Petit-Pont of the Hôtel-Dieu was also taken, its defenders killed and thrown into the Seine. George Sand, who was living on the quay, heard ‘furious clamour, tremendous cries’, then there was silence. By early morning, the insurrection still held out at only two points: the entrance to the faubourg Saint-Antoine and in the Saint-Avoye quarter.

Over the day of 6 June, resistance was concentrated in the Saint-Merry pocket. Columns of National Guard attacked the barricades from all sides – from both ends of the rue Saint-Martin, from the rue Aubry-le-Boucher, from the rue de la Verrerie … They were all repulsed, leaving their dead and wounded behind. Around three in the afternoon, however, two cannon were positioned at the level of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, enfilading the rue Saint-Martin. Initially, ‘the gunners fired with bullets and cast-shot; these projectiles wrought terrible damage to the shop fronts and façades of houses, but they did no great harm to our barricades.’ Until the cannon advanced to the level of the rue Michel-le-Comte: ‘Soon we saw our unhappy barricade [the first one, that of the rue Maubuée] shattered to pieces … and we were unable to defend it. … We took refuge in the carriage gateways adjacent to our destroyed fortifications on both sides of the street.’

The situation became critical, especially as munitions were beginning to run out. Jeanne proposed to his comrades to flee while there was still time, but all of them wanted to die at their post:

The rue Saint-Merry was already occupied by the troops of the line; a large number of troops were advancing through the rue Saint-Martin from the quays, and to top the difficulty of an already desperate position, a cannon positioned at the end of the rue Aubry-le-Boucher was starting to fire very heavily on the crossroads by no. 30. ‘My friends,’ I said to those around me, ‘if we go into the house we will be taken and shot; we still hold the rue Maubuée and only have facing us a company of conscripts. Let’s run against them and try to break through by bayonet!’

At the head of a dozen men, Jeanne managed to break through the lines. A hail of crockery, flowerpots and household objects slowed down the pursuing soldiers (‘I heard it said’, wrote Jeanne, ‘that even a piano had been dropped’), and the group succeeded in taking refuge in a friendly house, from where they heard the fusillade continuing. The last defenders of no. 30, those who had not been able to escape over the roofs, were massacred on the spot – like Enjolras and Grantaire in Les Misérables, after the barricade in the rue de la Chanverie was taken.

‘It was the best blood of France that ran in the rue Saint-Martin, and I do not believe that there was better fighting at Thermopylae than at the mouth of the alley of Saint-Merry and Aubry-le-Boucher, where at the last a handful of some sixty Republicans fought against sixty thousand troops of the line and National Guards,’ wrote Heine in his report of 16 June.10

In what has now become a tourist district, nothing, no monument or plaque, recalls the memory of these heroes of the barricades of June 1832. And yet thanks to Heine, to Hugo, even to the letter of Charles Jeanne, this remains a living memory for us.

____________

1Louis Blanc, History of Ten Years 1830–1840 (London: Chapman & Hall, 1844), vol. 1, p. 618. This gives a detailed account of the June days of 1832.

2‘French Affairs’, Works of Heinrich Heine, vol. 8 (London: Heinemann, 1893), p. 176.

3Blanc, History of Ten Years, vol. 2, p. 30.

4There is still a cavalry barracks on the boulevard Henri-IV. At that time the Célestins barracks was on the rue du Petit-Musc; the present barracks dates from the late nineteenth century. Regarding the quai Morland, the Louviers island was not yet connected to the Right Bank, and the Arsenal library was on the embankment, fronted by this quay.

5The veterans’ barracks was on the rue Mouffetard, close to the rue de l’Épée-de-Bois.

6The eighth arrondissement included the faubourg Saint-Antoine and the east of the Marais. The town hall was on the place Royale [now des Vosges]. The Château-d’Eau was close to the present place de la République.

7Blanc, History of Ten Years, vol. 2, p. 33.

8The Hôtel-Dieu was built on the Île de la Cité, facing the Seine, with an extension on the Left Bank to which it was connected by a bridge. The prefecture of police was at the point of the Île de la Cité, in the rue de Jérusalem.

9This letter, written by Jeanne in prison, was discovered by Thomas Bouchet, who published it in À cinq heures nous serons tous morts (Paris: Vendémiaire, 2011). The subsequent quotations are also taken from this work.

10Heine, ‘French Affairs’, p. 280.