Chapter 10

A Mythical Barricade: December 1851

After the massacres of June 1848, after the election of Louis Bonaparte as president of the republic in December the same year, after the pitiful unarmed insurrection of the republicans of the ‘Montagne’ in June 1849, the Second Republic slowly slipped towards the abyss. The Legislative Assembly, dominated by the Party of Order – Thiers, Montalembert, Falloux, Molé, Berryer – went so far as to abolish universal suffrage on 31 May 1850. In order to register on the electoral roll it was now necessary to prove one’s residence in the commune for three years, and proof of domicile was based on ‘inscription on the personal tax roll’, thus excluding a third of the electoral body – what Thiers called ‘the dangerous part of the great agglomerations of population’. ‘Faced with the flagrant advances of socialism’, Montalembert asked, ‘shall we remain helpless and silent?’ Was it not the duty of all honest people ‘to bring about that state of affairs which the president of the republic defined so well when he said that “The bad must tremble and the good be reassured”?’1

During the year 1851, the foremost issue was the revision of the constitution to allow Louis Bonaparte to stand for the presidential election of May 1852 – a vital concern for him, given the level of his debts.

Now imagine the French bourgeois, imagine how in the midst of this business his trade-crazy brain is tortured, whirled around and stunned by rumours of a coup d’état, by rumours that universal suffrage will be restored, by the struggle between parliament and the executive, by the Fronde-like war between Orleanists and Legitimists, by the communist conspiracies in southern France, by alleged jacqueries in the departments of Nièvre and Cher, by the publicity campaigns of the various presidential candidates, by the cheap and showy slogans of the newspapers, by the threats of the republicans to uphold the Constitution and universal suffrage by force of arms, by the preaching of the émigré heroes in partibus, who announced that the world would come to an end on the second Sunday in May 1852 – think of all this, and you will understand why the bourgeois, in this unspeakable, clamorous chaos of fusion, revision, prorogation, constitution, conspiration, coalition, emigration, usurpation and revolution, madly snorts at this parliamentary republic: Rather an end with terror than terror without end.

Bonaparte understood this cry.2

The coup d’état was launched on the night of 1–2 December, with the arrest of the potential leaders of a resistance:

It was a question of arresting at their own homes seventy-eight Democrats who were influential in their districts, and dreaded by the Élysée as possible chieftains of barricades. It was necessary, a still more daring outrage, to arrest at their houses sixteen Representatives of the People. For this last task were chosen among the Commissaries of Police such of those magistrates who seemed the most likely to become ruffians.3

During the same night, the workers at the Imprimerie Nationale were engaged in the greatest secrecy in printing posters announcing the coup d’état. ‘Each [of the compositors] was placed between two gendarmes, and forbidden to utter a single word, and then the documents which had to be printed were distributed throughout the room, being cut up in very small pieces, so that an entire sentence could not be read by one workman.’4 Early in the morning, the National Assembly was occupied by the troops.

The representatives of the Party of Order met in the town hall of the tenth arrondissement, in the rue de Grenelle, and declared the dismissal of the prince-president – his dismissal, rather than outlawing, which would have had more serious implications. ‘Popular armed resistance, even in the name of the law, seemed sedition to them. The utmost appearance of revolution which they could endure was a regiment of the National Guard, with their drums at their head; they shrank from the barricade; Right in a blouse was no longer Right, Truth armed with a pike was no longer Truth, Law unpaving a street gave them the impression of a Fury.’5 These 300-odd right-wing deputies would be taken to the Orsay barracks, then conveyed in prison carriages to Mazas and Mont Valérien: ‘the entire Party of Order arrested in a body and taken to prison by the sergents de ville!’6

Meanwhile some sixty deputies of the left, including Edgar Quinet, Schoelcher, Carnot and Hugo himself, met in the apartment of a friend on the rue Blanche. Hugo proposed they should issue a proclamation:

‘Dictate,’ said Baudin to me, ‘I will write.’

I dictated:

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte is a traitor.

He has violated the Constitution.

He is forsworn.

He is an outlaw …’7

They then decided to try to energise Paris, starting with the working-class districts. Hugo remembered Auguste, a wine merchant whose life he had saved in 1848: ‘I thought that he might give me information about the faubourg St. Antoine, and help us in rousing the people.’ Having with difficulty found Auguste’s shop, on the rue de la Roquette, he entered:

He knew me at once, and came up to me.

‘Ah, Sir,’ said he, ‘it is you!’

‘Do you know what is going on?’ I asked him.

‘Yes, sir.’

This ‘yes, sir’, uttered with calmness, and even with a certain embarrassment, told me all. Where I expected an indignant outcry I found this peaceable answer. It seemed to me that I was speaking to the faubourg St. Antoine itself. I understood that all was at an end in this district, and that we had nothing to expect from it.

Auguste explained himself, and the indirect style Hugo uses here emphasises the sadness of his words:

To tell the whole truth, people did not care much for the Constitution, they liked the Republic, but the Republic was maintained too much by force for their taste. In all this they could only see one thing clearly, the cannon ready to slaughter them – they remembered June, 1848 – there were some poor people who had suffered greatly – Cavaignac had done much evil – women clung to the men’s blouses to prevent them from going to the barricades – nevertheless, with all this, when seeing men like ourselves at their head, they would perhaps fight, but this hindered them, they did not know for what.8

In the evening of this first day of the coup d’état, the representatives of the republican left decided despite everything to try to rouse the faubourg Saint-Antoine. They agreed to meet at nine the next morning in the Salle Roysin, a large café that had been the meeting-place of the social-democratic club in 1848. ‘Rebellion in the Élysée, the government in the faubourg Saint-Antoine!’ Hugo exclaimed.

We have an eye-witness account of the events of that morning by a courageous participant, Victor Schoelcher.9 On the way to the Salle Roysin,

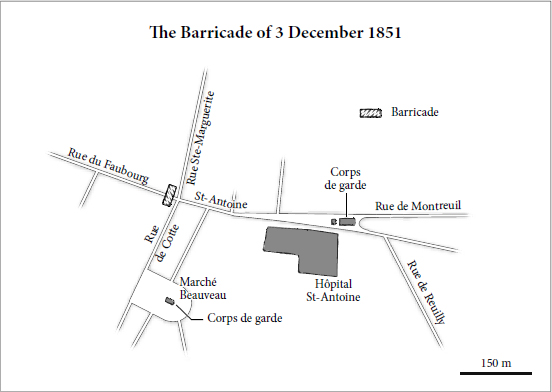

proceeding on foot through the faubourg Saint-Antoine, we saw groups of workers gathered at the doors of their houses. They were dejected, but calm, and when we asked: ‘Are you doing nothing? Are you waiting for the empire?’ they all replied: ‘No, no, never!’, adding: ‘What do you want us to do? We have no weapons, we were disarmed after June 1848!’ These last words were repeated to us ten times by different groups. Oh, those who disarmed the people then were guilty of much! … Despite everything, the republican representatives,10 with some twenty bold men in blouses and suits, decided on the first barricade erected against the ex-president’s insurrection … We immediately set to work to make a barricade across the faubourg at the corners of the rues de Cotte and Sainte-Marguerite [now Trousseau]. A dairy cart, another baker’s cart, a large wagon and an omnibus were successively seized, unhitched and turned upside down … We possessed only three rifles taken from two passing soldiers accompanied just by an old sergeant. From where we were we could see the small building of the Corps de garde in the middle of the faubourg Saint-Antoine, near the rue de Montreuil. We fell on this post and forced it to hand over its weapons, ten or twelve rifles, and its munitions. We then headed for the guard post of the Marché-Noir [now Aligre]. The same expedition, again led by deputies, was carried out with the same audacity and the same success.

A few minutes after we returned to the barricade, around half past nine, we noticed an infantry detachment of the 19th light regiment approaching from the direction of the Bastille. … When the detachment came close, one of us said to his colleagues: ‘Let’s move forward.’ Immediately the representatives climbed on the overturned vehicles, and this man, addressing the citizens, said: ‘Friends, not a shot before the troops open fire.’ … The three companies proceeded silently at a funeral pace. We made a sign to them to halt; the captain at their head replied with a negative sign; seven [of us] then descended and advanced towards him. The captain threatened: ‘Go back or I’ll fire.’ ‘You can kill us,’ the Montagnards replied with one voice, ‘but you will not make us retreat; our bodies will serve to cover the people!’

They could have killed us, but they did not want to. They passed between us. Nine ranks of soldiers, coming towards the barricade, successively found themselves face to face with us; none of them struck. The troop loosed only one volley, and it was then that our colleague Baudin, who had remained standing fast on one of the vehicles, received three bullets in the head that killed him immediately. None of us, further forwards, saw him fall. … The representative of the people Baudin will be inscribed on the glorious and too long list of the martyrs of liberty. His death was not without bitterness. ‘We didn’t want to sacrifice ourselves for the “twenty-five francs”,’ one worker said. ‘The twenty-five francs’! That is what even some of our own friends foolishly called us.11 ‘You shall see’, Baudin replied, ‘how someone dies for twenty-five francs!’ And it was precisely he who laid down his life for the Constitution, bequeathing to posterity his name and a sublime phrase!

Hugo writes that the evening was full of menace. Groups formed on the boulevards, soon combining into a tremendous crowd:

Throughout that long line from the Madeleine to the Bastille, the roadway nearly everywhere, except (was this on purpose?) at the Porte St Denis and the Porte St Martin, was occupied by the soldiers – infantry and cavalry, ranged in battle-order, the artillery batteries being harnessed; on the pavements on each side of this motionless and gloomy mass, bristling with cannon, swords, and bayonets, flowed a torrent of angry people.12

Small barricades were erected in the old insurrectionary quarters, between the Hôtel de Ville and the boulevards. The fighters did not try to defend these at any cost, but rather used them to dodge the attacks of the troops, abandoning one position and taking up another. At the Élysée there was a certain disquiet. Morny, the new interior minister, himself redrafted a proclamation by Saint-Arnaud, the new minister of war, ending it with the words: ‘Any individual taken constructing or defending a barricade, or with weapons in hand, will be shot.’13

On the morning of 4 December, barricades proliferated within a quadrilateral bounded by the Halles and the boulevards, the rue du Temple and the rue Montmartre.

At eleven o’clock in the morning from Notre-Dame to the Porte St Martin there were seventy-seven barricades. Three of them, one in the rue Maubuée, another in the rue Bertin-Poirée, another in the rue Guérin-Boisseau, attained the height of the second stories; the barricade of the Porte St Denis was almost as bristling and as formidable as the barrier of the faubourg Saint-Antoine in June, 1848.14

But the military chiefs had assembled some 30,000 men in the city centre, who moved into action in the afternoon. At two o’clock, five brigades were positioned on the boulevards between the rue de la Paix and the faubourg Poissonnière:

In the twinkling of an eye there was a butchery on the boulevard a quarter of a league long. Eleven pieces of cannon wrecked the Sallandrouze carpet warehouse. The shot tore completely through twenty-eight houses. The baths of Jouvence were riddled. There was a massacre at Tortoni’s. A whole quarter of Paris was filled with an immense flying mass, and with a terrible cry. Everywhere sudden death. A man is expecting nothing. He falls.15

A terrifying blow had to be dealt. This explains the massacre of an unarmed crowd, the slaughter inside buildings, the deliberate carnage. ‘On a given signal,’ wrote Odilon Barrot in his Mémoires, ‘columns of infantry and cavalry rushed on the crowd. This murder was not a mistake, a bit of terror was needed, if only to expand the event.’16

Today this crime has been amnestied, so to speak, drowned in the rampant rehabilitation of Louis Bonaparte that has already been under way for years – witness the name of Napoléon III given to the esplanade in front of the Gare du Nord, or Philippe Séguin’s book entitled Louis Napoléon le Grand (1990). The death of Baudin on the barricade has likewise been buried in a remote corner of collective memory; his statue was melted down under the Occupation, and the street that bears his name is one of the most dismal in the eleventh arrondissement.17 Few remember that the name of Baudin was a weapon against the regime at the end of the empire, when in 1868, on the initiative of Charles Delescluze, a subscription was launched in the press to erect a monument to him – inspired by a planned trial of radical republicans for ‘incitement to hatred and contempt for the government’.

____________

1Cited in Henri Guillemin, Le Coup du 2 décembre (Paris: Gallimard, 1951), p. 210.

2Karl Marx, ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’, in Surveys from Exile (London: Verso, 2011), pp. 227–8.

3Victor Hugo, History of a Crime (New York: Mondial, 2005), p. 11. Hugo’s book, an incomparable account of the events of 2–4 December, is subtitled ‘The Testimony of an Eye-Witness’.

4Ibid., p. 13.

5Ibid., p. 73.

6Ibid., p. 83.

7Ibid., p. 101.

8Ibid., pp. 111–12.

9Victor Schoelcher, Histoire des crimes du 2 décembre (2 vols, Brussels, 1852). The quotations are taken from vol. 1, pp. 190–210.

10‘They were eight on the barricade: Baudin, Bruckner, Deflotte, Dulac, Maigne, Malardière, Schoelcher [who writes of himself in the third person], and another whom we cannot name because the prosecutors are unaware of him.’

11Under the Second Republic deputies received twenty-five francs a day.

12Hugo, History of a Crime, p. 194.

13Guillemin, Le Coup du 2 décembre, p. 386.

14Hugo, History of a Crime, p. 265. The June barricade on the faubourg Saint-Antoine is described at length in book V of Les Misérables.

15Ibid., p. 270.

16Cited in Guillemin, Le Coup du 2 décembre, p. 398. My emphasis.

17A plaque was however placed in 1879 on the building at no. 151, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine.