Chapter 11

The Barricades of the Commune: May 1871

Seventy days elapsed between 18 March 1871, when the people of Paris seized the cannon of the National Guard in Montmartre, and 28 May, when the last shots were fired in Belleville. It was only in the final week that the barricade played a part, yet this is remembered as the symbol of the Paris Commune.

How did things get to such a pass, in that tragic week, when the Commune still possessed the assets of weapons, fortifications and cannon?1

A first reason is that the city of Paris very soon found itself alone in its struggle. The communes of Marseille, Narbonne and Limoges were subdued within days, enabling Thiers to concentrate his forces around the capital.

Another major reason was the friction within the Paris movement. The central committee of the National Guard, elected by the battalions of the popular quarters, was the revolutionary body that took possession of the city on 18 March. It would cede power to the Commune elected by universal suffrage, but without dissolving itself: it continued to play an ill-defined role, a factor of discord and confusion. The Commune itself was divided into two wings from its very first session. The majority was made up of ‘Jacobins’, haunted by the memory of 1793 – these included the great Charles Delescluze – along with Blanquists such as Eudes, Ferré, Rigault and Ranvier. These ‘romantics’, as Lissagaray called them, were republicans who favoured a centralist, authoritarian politics. The minority, for their part, were Internationals, Proudhonists or independents, champions of social democracy and hostile to republican centralization.2 They included Courbet, Fränkel, Lefrançais, Longuet, Malon, Tridon (despite his being a follower of Blanqui), Vallès and Vermorel. Their opposition would become more fiery when, in the face of general disorganization, the majority decided on the formation of a Committee of Public Safety – which was far from working wonders.

When the Versaillais entered Paris, all these tendencies united to confront the danger, but it was too late: the defence was not ready. Successive delegates for war (the Commune did not have ministers) came and went without any of them showing signs of competence: Cluseret (‘We must admit that the Commune possesses a delegate for war of great calm and with a remarkable power of sleep. Good heavens, what a sleeper!’3) was replaced by his chief of staff, Rossel, a professional soldier, ‘absolutely foreign to the cause for which we struggle – how could that communion of ideas that is indispensable for success be established between his troops and himself?’4 On the brink of disaster, Delescluze was appointed delegate for war: a superb symbol, but the man himself was old, tired, ill, and ignorant of military matters. The Commune’s army never had a real head, which was clearly a fatal lack.

A barricades commission was established in early April, under Rossel, an officer of the engineers. It decided to construct lines of barricades around the city. The idea was for barricade-fortresses on the main communication routes, and lighter constructions else-where.5 Napoléon Gaillard, a master shoemaker, was charged by Rossel to undertake this work. In fact, only a few of the large barricades envisaged were in place to meet the Versaillais: the largest of these – the ‘Château-Gaillard’ – blocked the rues Saint-Florentin and Rivoli at the corner of the place de la Concorde. Others were erected at the Trocadéro, on the rue de Castiglione, and in the fourteenth arrondissement on the avenue de Maine at the Porte d’Orléans, but this was very far from being the second defensive wall originally planned. ‘These were no longer the traditional redoubts two storeys high. Save four or five in the rue Saint-Honoré and the rue de Rivoli, the barricades of May consisted of a few paving-stones hardly a man’s height; behind these sometimes a cannon or a machine-gun; and in the midst, wedged in by two paving-stones, the red flag, the colour of vengeance.’6

The vanguard of the Versaillais troops entered Paris in the early hours of 21 May, flooding in ‘through the five gaping wounds of the gates of Passy, Auteuil, Saint-Cloud, Sèvres and Versailles. The greater part of the fifteenth arrondissement was occupied, the Muette taken; all Passy and the heights of the Trocadéro were taken.’7 During this time, the general council of the Commune held its last session in the Hôtel de Ville. It dealt only with regular business.

On the morning of 22 May, a proclamation written by Delescluze could be read on the walls:

Enough of militarism! No more staff-officers with their gold-embroidered uniforms! Make way for the people, for the combatants bare-armed! The hour of the revolutionary war has struck … The people know nothing of learned manoeuvres. But when they have a gun in their hands and paving-stones under their feet, they fear not all the strategists of the monarchical school.8

In the words of Lefrançais, ‘it was essential to put an end to this nightmare of interminable siege … Better for all, in sum, this definitive face-to-face than the indefinite continuation of a struggle at a distance and with no outcome. The invaders were awaited almost with impatience, on the heights of Passy and the Trocadéro that they had taken possession of during the night.’9

As it seemed impossible to mount a defence on the wide arteries of the west of the city, the Federals withdrew to a line running from the Batignolles to the Gare Montparnasse, via Saint-Augustin and Concorde. But this line soon collapsed, except at the Batignolles which formed a forward defence for Montmartre; here the Versaillais were stopped between the place Clichy and La Fourche. The Butte Montmartre, however, which could have been an impregnable fortress, remained silent. ‘Eighty-five cannon and about twenty machine-guns were lying there, dirty, pell-mell, and no one during these eight weeks had even thought of cleaning them.’ On the Left Bank, where the rue de l’Université, the rue du Bac and the boulevard Saint-Germain were barricaded, soldiers filed through the avenue du Maine to the Gare Montparnasse. ‘This position, of supreme importance, had been utterly neglected; about twenty men defended it, and they were soon short of cartridges, and obliged to retreat to the rue de Rennes, where, under the fire of the troops, they constructed a barricade at the top of the rue du Vieux Colombier.’10

By the evening of the 22nd, the Versaillais line stretched from the Gare des Batignolles to the Gare Montparnasse, by way of the Gare Saint-Lazare, Saint-Augustin, the Palais-Bourbon and the boulevard des Invalides. But ‘Paris, the old insurgent, resumed her combative physiognomy. Dispatch riders dashed through the streets, and remainders of battalions came to the Hôtel de Ville, where the Central Committee, the Committee of Artillery, and all the military services were concentrated.’11

Early in the morning of the 23rd, the Versaillais launched a movement that skirted the fortifications and took all the northern gates from behind, from Asnières to Saint-Ouen – the Prussians had let them pass. The Batignolles barricades gave way one after the other. Columns attacked Montmartre through the rue Lepic and the rue Clignancourt. The Montmartre cemetery saw bitter fighting, with Louise Michel taking up a rifle: ‘This time the shell fell close to me, coming down through the branches and covering me with flowers, close to Murger’s tomb. … When I returned to my comrades, near the tomb on which stands the bronze statue of Cavaignac, they said to me: now keep still.’12

On the place Blanche, at the mouth of the rue Lepic, the famous women’s barricade, commanded by the Russian revolutionary Elisabeth Dmitrieff and made up of militants from the Union des Femmes, held out for several hours while other women came to reinforce the barricade on place Pigalle, at the bottom of the rue Houdon.13

Resistance was more effective on the other bank of the Seine, particularly at the two crossroads of Croix-Rouge and Vavin, where Varlin managed to hold out for two days. He only abandoned this sector when fire and mortar shells had made it a field of ruins. Here again, however, the Versaillais, turning around to the south along the ramparts, came up through the avenue de Maine to the place d’Enfer [now Denfert-Rochereau]. On the Butte-aux-Cailles, Wroblewski, one of the best officers of the Polish insurrection of 1863, ‘installed a battery of eight pieces and two batteries of four … a dominant position between the Panthéon and the forts; he fortified the boulevards d’Italie [now Auguste-Blanqui], de l’Hôpital, and de la Gare [now Vincent Auriol]. He established his headquarters at the mairie des Gobelins, with reserves at the place d’Italie, the place Jeanne d’Arc, and Bercy.’14

On the evening of 23 May, the Versaillais line extended from the Porte de la Chapelle to the place d’Enfer, by way of the Gare du Nord, the new Opéra, the boulevard des Italiens and the rue du Bac. ‘The place de la Concorde and the rue Royale, surrounded on their flanks, stood out like a promontory in the midst of a tempest,’ wrote Lissagaray. That evening the massacre of prisoners began, and of all those suspected of taking part in the insurrection. Each army corps had its provost marshal who ordered executions and, so as to proceed more quickly, supplementary provosts were posted in the conquered streets.

During the night the Tuileries burned. ‘Formidable detonations were heard from the palace of the kings, whose walls were falling, its vast cupolas giving way. … The red tide of the Seine reflected the monuments, thus redoubling the conflagration.’15 On the Left Bank, the Légion d’honneur building and the Cour des Comptes likewise went up in flames, so that ‘the rue Royale to St Sulpice seemed a wall of fire divided by the Seine.’16 At ten in the evening, the barricade in the rue Saint-Florentin was evacuated, the Versaillais occupied the place Vendôme and took the barricade on the rue de Castiglione from behind. The Federals withdrew with great difficulty to the Hôtel de Ville.

In the morning of 24th May, the Versaillais pushed forwards on all fronts. They cannonaded the Palais-Royal, reached the Bourse and descended towards the Halles, where they met very strong resistance around Sainte-Eustache. On the Left Bank, they reached the Val-de-Grâce and approached the Panthéon. At eight o’clock, members of the Commune met at the Hôtel de Ville and decided to evacuate it. The building was set on fire, and the services of the war department withdrew to the mairie of the eleventh arrondissement. What remained of the defence line was cut in two, and communication between the two banks became dangerous.

On the Left Bank, the Federals abandoned the rue Vavin, blowing up the powder works at the Luxembourg. Varlin and Lisbonne retreated to the Panthéon, defended by three barricades, the farther and higher one running between the mairie of the fifth arrondissement and the law faculty building. But the Versaillais surged across the Pont Saint-Michel, where firing had stopped for lack of munitions. In the afternoon, the Panthéon was taken and the whole of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève fell into the hands of the army. The massacres immediately commenced: on the rue Saint-Jacques, forty prisoners were shot.

At the mairie of the eleventh arrondissement, where the remnants of the battalions of the conquered quarters were gathered, it was Delescluze who spoke:

‘I propose,’ said he, ‘that the members of the Commune, engirded with their scarfs, shall make a review of all the battalions that can be assembled on the boulevard Voltaire. We shall then at their head proceed to the points to be reconquered.’ … Behold, in the midst of this defeat, this old man upright, his eyes luminous, his right hand raised defying despair, these armed men fresh from the battle suspending their breath to listen to this voice which seemed to ascend from the tomb. There was no scene more solemn in the thousand tragedies of that day.17

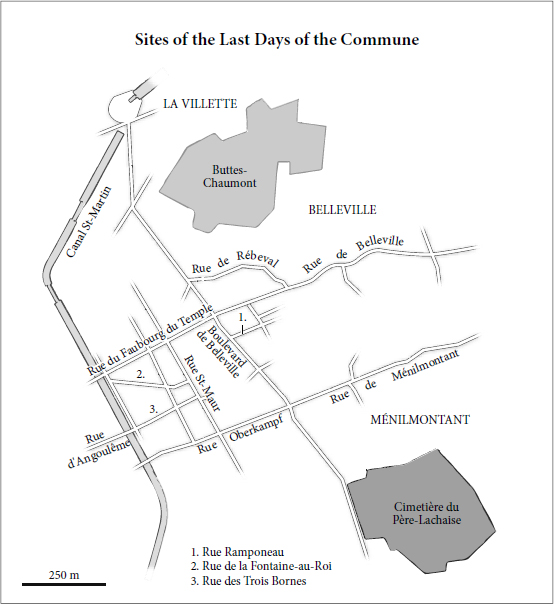

The defence of the east of Paris was organized. Around the Bastille, barricades defended the entry to the rue and faubourg Saint-Antoine. On the place du Château-d’Eau [now de la République], a wall of paving-stones blocked the entrance to the boulevard Voltaire. The rues Oberkampf, Angoulême, la Fontaine-au-Roi and Faubourg du Temple were hastily barricaded at their lower ends.

The massacre continued in the neighbourhoods occupied by the army. ‘‘These are no longer soldiers accomplishing a duty’’, said a conservative journal, La France. And indeed these were hyenas, thirsting for blood and pillage. In some places it sufficed to have a watch to be shot. The corpses were searched, and the correspondents of foreign newspapers called those thefts the last perquisition.’18 In response the Federals executed Darboy, the archbishop of Paris, Deguerry, vicar of the Madeleine, and three Jesuits imprisoned with them in La Roquette.

Barricade on the rue d’Allemagne (now avenue Jean-Jaurès) at the crossroads with the rue de Sébastopol (now rue Lally-Tollendal), 1871

On the night of the 24th, the Versaillais troops occupied a great swath surrounding the eleventh, nineteenth and twentieth arron-dissements, while Paris continued to burn.

At midday on the 25th, the army attacked the Butte-aux-Cailles from the avenue d’Italie in the south and the Gobelins in the north. ‘For three hours a prolonged and obstinate firing enveloped the Butte aux Cailles, battered down by the Versaillese cannon, six times as numerous as Wroblewski’s. … protected by the fire of the Austerlitz Bridge, the able defender of the Butte aux Cailles passed the Seine in good order with his cannon and a thousand men.’19 The whole of the Left Bank was now in the hands of the Versaillais.

The barricades defending the entrance to the boulevard Voltaire and the boulevard du Temple came under fire from the Prince-Eugène barracks [of the Republican Guard, on the place de la République], from the boulevard Magenta and the rue Turbigo. ‘The place du Château d’Eau was ravaged as by a cyclone. The walls crumbled beneath the shells and bullets; enormous blocks were thrown up; the lions of the fountains perforated or broken off, the basin surmounting it shattered. Fire burst out from twenty houses. The trees were leafless, and their broken branches hung like limbs all but parted from the main body.’20

Delescluze came down the boulevard Voltaire towards the square. He wore

his ordinary dress, black hat, coat, and trousers, his red scarf, inconspicuous as was his wont, tied round his waist. Unarmed, he leant on a cane. … At about eighty yards from the barricade the guards who accompanied him kept back, for the projectiles obscured the entrance of the boulevard.

Delescluze still walked forward. Behold the scene; we have witnessed it; let it be engraved in the annals of history. The sun was setting. The old exile, unmindful whether he was followed, still advanced at the same pace, the only living being on the road. Arrived at the barricade, he bent off to the left and mounted upon the paving-stones. For the last time his austere face, framed in his white beard, appeared to us turned towards death. Suddenly Delescluze disappeared. He had fallen as if thunder-stricken on the place du Château d’Eau.21

By the evening, only two whole arrondissements remained in the hands of the Commune, the nineteenth and twentieth, along with half of the eleventh.

On the morning of Friday, 26 May, the fighting was concentrated on the Bastille, under attack from two sides, the boulevard Mazas [now Diderot] and the boulevard Beaumarchais:

Entrenched in the houses, the Federals fell, but neither yielded nor retreated; and, thanks to their self-sacrifice, the Bastille for six hours still disputed its shattered barricades and ruined houses. … Leaning against the same wall the sons of the combatants of June fought for the same pavement as their fathers. … The house at the corner of the rue de la Roquette, the angle of the rue de Charenton, disappeared like the scenery of a theatre, and amidst these ruins, under these burning beams, some men fired their cannon, and ten times raised the red flag, ten times struck down by Versaillese fire.22

The Bastille succumbed at around two in the afternoon. There was still fighting at La Villette, around the Rotonde, the quai de Loire and the rue de Crimée. But a fire broke out on the docks, full of petroleum and explosives, and the barricade defenders had to retreat to the twentieth arrondissement.

It was on that evening of the 26th that the hostages were shot on the rue Haxo. These were thirty-four gendarmes captured at Belleville and Montmartre on 18 March, ten Jesuits, monks and priests, and four imperial spies. ‘And yet for two days the soldiers taken prisoner passed through Belleville without exciting a murmur; but these gendarmes, these spies, these priests, who for fully twenty years had trampled upon Paris, represented the Empire, the bourgeoisie, the massacres under their most hateful forms.’23

On the morning of Saturday, 27 May, Jules Vallès was in the rue des Trois-Bornes: ‘We stayed up all night. At dawn, Cournet, Theisz, Camélinat and myself went back towards Paris. The rue d’Angoulême still held out. There, the 209th, the battalion whose standard-bearer was Camélinat, was desperately defending itself.’24 The Versaillais occupied the Montreuil and Bagnolet gates, the place du Trône [now de la Nation], and spread from there into Charonne. From La Villette, their mortars devastated the Buttes-Chaumont. The artillery of the Federals, massed on the place des Fêtes, stopped firing in the afternoon for lack of munitions, and their gunners joined those defending the rue Fessart and the rue des Annelets:

Since four o’clock in the afternoon the Versaillese had been laying siege to the Père Lachaise, which enclosed no more than 200 Federals, resolute, but without discipline or foresight. The officers had been unable to make them embattle the walls. Five thousand Versaillese approached the enceinte from all sides, while the artillery of the bastion furrowed the interior. … At six o’clock the Versaillese, not daring, in spite of their numbers, to scale the enceinte, cannonaded the large gate of the cemetery, which soon gave way, notwithstanding the barricade propping it up. Then began a desperate struggle. Sheltered behind the tombs, the Federals disputed their refuge foot by foot; … in the vaults they fought with side-arms. … The darkness that set in early did not end the despair.25

At five in the morning on Sunday, 28 May, ‘we were at the giant barricade at the foot of the rue de Belleville, almost facing the Salle Favié,’ wrote Vallès:

I had drawn lots with the officer replacing me as to who would go and lie down for a while. It fell to me and I stretched out in an old bed at the back of an abandoned apartment. … We replied with rifles and cannon to the terrible fire directed against us. In the windows of La Veilleuse,26 and of all the houses on the corner, our people had put straw mattresses whose stuffing was smouldering and punctured.27

In the course of the morning the resistance was reduced to the small quadrilateral bounded by the rue du Faubourg-du-Temple, the rue Saint-Maur and the boulevard de Belleville.

Several streets today compete for the honour of having hosted the final barricade of the Commune. For Lissagaray, ‘the last barricade of the May days was in the rue Ramponeau. For a quarter of an hour a single Federal defended it. Thrice he broke the staff of the Versaillese flag hoisted on the barricade of the rue de Paris [now de Belleville]. As a reward for his courage, this last soldier of the Commune succeeded in escaping.’ Legend has it that this soldier was Lissagaray himself.

For others, the last barricade was that on the rue Rébeval; for Louise Michel it was that of the rue de la Fontaine-au-Roi:

An immense red flag floated above the barricade. The two Ferrés were there, Théophile and Hippolyte, also J.-B. Clément, Cambon, a Garibaldian, Varlin, Vermorel, Champy. The barricade on the rue Saint-Maur had just succumbed, that of La Fontaine-au-Roi stubbornly spat out fire in the bloody face of Versailles. … At the moment when the last shots were fired, a young woman arrived from the barricade on the rue Saint-Maur, to offer her services. They tried to push her away from this place of death, but she stayed despite them.28

This was the woman to whom Jean-Baptiste Clément would dedicate his song, Le Temps des cerises.

At one o’clock, it was all over.

____________

1See Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871 [1876] (London: Verso, 2012), an indispensable work, by a participant who spent the rest of his life studying the history of the events he had lived through.

2In his Enquête sur la Commune de Paris published by the Revue Blanche in 1897, Lefrançais wrote: ‘The twenty-five years that have passed since then have only convinced me more that this minority were right, and that the proletariat will never succeed in truly emancipating itself without ridding itself of the Republic, the last form of authoritarian government, and by no means the least harmful’ (Gustave Le français, Souvenirs d’un révolutionnaire, new edition, [Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2011], p. 105).

3Lefrançais, Souvenirs d’un révolutionnaire, p. 389.

4Ibid., p. 401.

5Marcel Cerf, ‘La barricade de 1871’, in Alain Corbin and Jean-Marie Mayeur, eds, La Barricade (Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1997), pp. 323–35.

6Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune, p. 258.

7Ibid., p. 248.

8Ibid., pp. 249–50.

9Lefrançais, Souvenirs d’un révolutionnaire, p. 420.

10Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune, p. 253.

11Ibid.

12Louise Michel, La Commune, histoire et souvenirs [1898] (Paris: La Découverte, 1999), pp. 232–3. The Cavaignac she refers to here is Godefroy Cavaignac, one of the republican leaders under the July monarchy, who died of tuberculosis in 1845. The recumbent figure on his tomb was the work of Rude.

13Alain Dalotel, ‘La barricade des femmes’ (in Corbin and Mayeur, eds, La Barricade, pp. 350–5), emphasises that there could be an element of legend in this episode.

14Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune, p. 263.

15Ibid., p. 267.

16Ibid.

17Ibid., p. 275.

18Ibid., p. 277.

19Ibid., pp.283, 284.

20Ibid., p. 287.

21Ibid., pp. 287–8.

22Ibid., p. 292.

23Ibid., p. 297.

24Jules Vallès, L’Insurgé [1886] (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1908), p. 320. Camélinat, a sculptor in bronze and a member of the International, was head of the mint during the Commune.

25Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune, p. 300.

26This café still exists on the corner of the rue de Belleville and the boulevard de Belleville. The building has been recently reconstructed.

27Vallès, L’Insurgé, pp. 321–2. The Salle Favié stood near the site of the present café Les Folies.

28Michel, La Commune, p. 264.