STEP THREE

PARALLEL LINES

AS WE SEE THEM

PARALLEL LINES

RELATED TO

ONE-POINT PERSPECTIVE

PARALLEL LINES AS WE SEE THEM

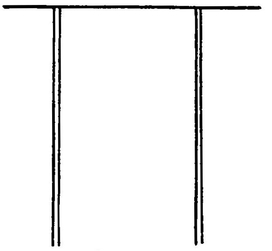

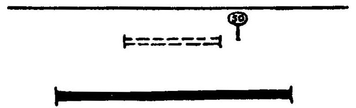

Knowing that the rails are parallel, why do we not draw them this way?

Instead of this way?

The two rails of the track are always the same distance apart.

When two or more lines always remain the same distance apart they are called parallel lines.

In a perspective drawing we do not actually draw these lines parallel. Why not?

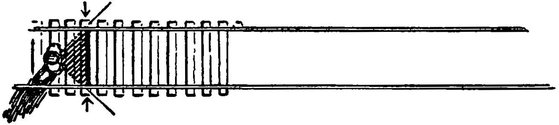

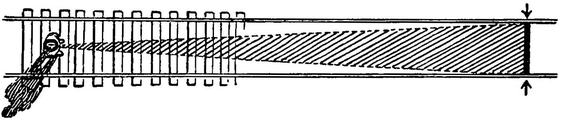

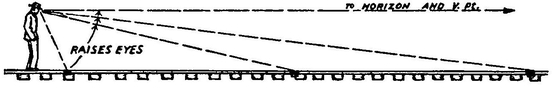

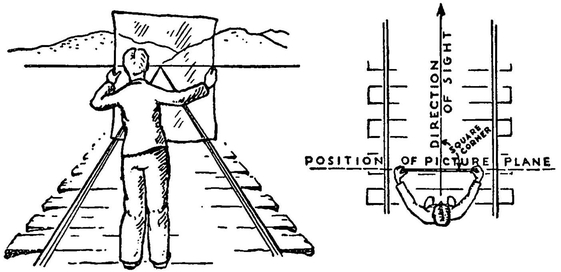

Let us look straight down on a person standing on the track and see what is happening.

When he looks down at the track at his feet his eyes must take in a wide area in order to see both rails.

He sees this width in front of him, as indicated by the heavy black line.

As he raises his eyes and looks fifty feet in front of him he sees the same width of tracks but within a much narrower area.

For this reason the track appears narrower as he looks farther away.

The shaded portion on the sketch shows this area.

The portion he sees fifty feet away is shown by the black line.

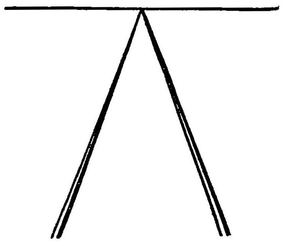

As he raises his eyes to the horizon the same width of track appears in so narrow an area that it looks like no width at all. This is the vanishing point.

Thus the nearer he looks, the wider appears the spread of the track, and the farther away he looks the narrower it appears until it becomes a point at his eye-level.

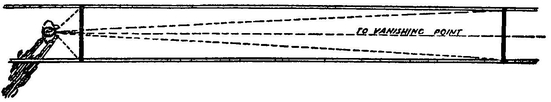

This wide or narrow area is perhaps better understood if we think of the person drawing these widths on a piece of glass held upright as shown on page 28.

The above sketch shows how the man, in order to see farther along the track, must raise his eyes.

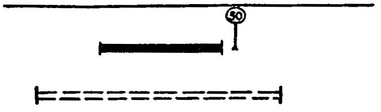

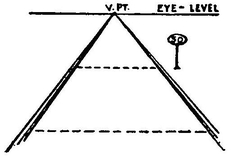

And so the man sees the track this way.

Instead of this way.

PARALLEL LINES AND ONE-POINT PERSPECTIVE

Parallel lines are two or more lines that extend in the same direction and remain the same distance apart.

The two opposite sides of a table are parallel, the boards of the floor, the rails of a track.

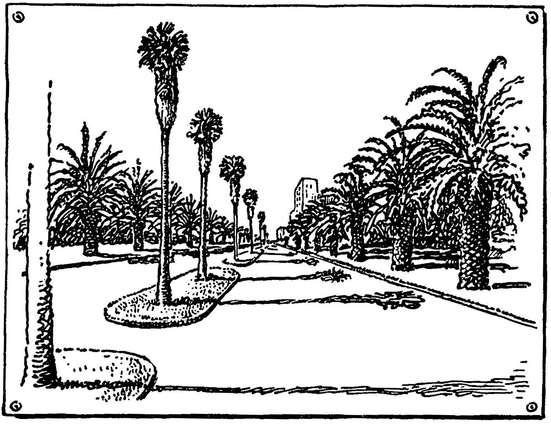

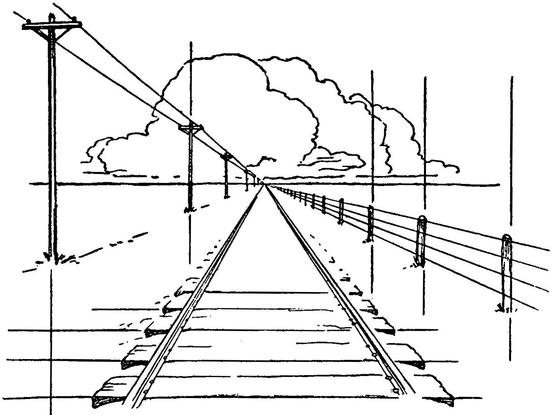

We know that the two parallel rails of the track appear to converge at a point in the distance. Now take notice of the fences and telegraph wires that follow the .tracks; they also converge at this same point.

A group of parallel lines in a perspective drawing, if extended, meet at the same point.

There are two exceptions to this rule. These exceptions are shown in the drawing.

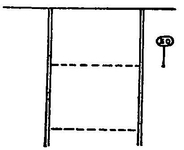

(1) When we face the vanishing point of a group of parallel lines (as in the picture) we have one-point perspective; in this case the left-and-right lines, like the ties of the track, are all parallel with the horizon. There is no vanishing point.

(2) Up and down (perpendicular) lines, like the telegraph poles and fence posts, are also drawn parallel but without a vanishing point. (Perpendicular lines are explained on page 45.)

The general rule for (1) and (2) is that parallel lines which are also parallel to the picture plane do not appear to converge at a point. The picture plane is explained on the next page.

A good example of parallel upright lines is a forest of tall straight trees. The trees farther back in the forest appear smaller, thus suggesting depth or distance.

THE PICTURE PLANE

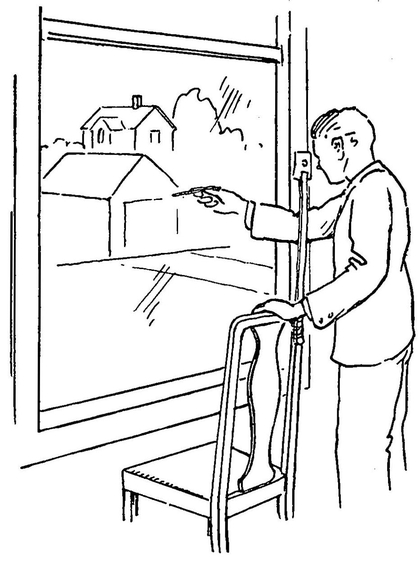

Hold a sheet of cellophane or glass upright before your eyes. You can see the object or scene before you through the transparent sheet. If you trace this scene as you see it on the sheet you will have a drawing in perspective. The transparent sheet can be thought of as a sheet of drawing paper or an artist’s canvas. When held in this position it may be called the picture plane. We think of perspective drawings as made on this picture plane.

The picture plane stands upright (perpendicular) between the artist and the object he is drawing. Also, the picture plane is placed directly across (at right angles to) the line of direction in which the artist is looking. The diagram at the right explains this.

Drawing in perspective on the picture plane can be self-explained by standing in front of a window and with a china marking pencil tracing on the glass the outlines of the buildings as you see them.

A paper with a hole in it can be set at arm’s length to help fix the point of view. Look through this hole and sketch as if the window were the sheet of paper. Simply trace on the glass the buildings and landscape as you see them beyond the window. The result is a perspective drawing.

Suppose we remove the windowpane with this drawing and lay it on the table. On the table it looks like any other perspective drawing done on a piece of paper.

How is it possible to make this drawing without first tracing it on an upright piece of glass? The following steps will explain how this can be done.

REMEMBER

The two rails of a track are parallel. These two parallel lines, when shown in a perspective drawing, come together at a point.

When two parallel lines meet at a point all other lines parallel to these two meet at the same point.

You lower your eyes to see your feet.

You raise your eyes to see objects on the ground at a distance.

The picture plane stands upright between the artist and the object he is drawing.

PROBLEMS

Draw the top view of a man standing at the end of a long narrow table. Show the difference in the area of his vision when looking at the width of the far end of the stable compared with that of the near end.

Stand in the center of a straight level highway. Draw it as you see it—disappearing in the distance. Add a sidewalk parallel to it. Add two rows of telephone poles, a row on each side. Add a fence beside the walk.

Draw a railroad on the prairie sketched from the center of the track. Show a highway crossing it in the foreground.