STEP SEVEN

SHOWING HOW THE

VANISHING POINTS

MOVE IN RELATIONSHIP

TO ONE ANOTHER

DIRECTIONS OF VANISHING POINTS

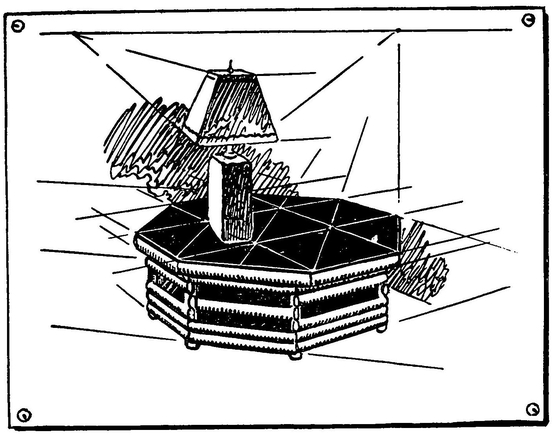

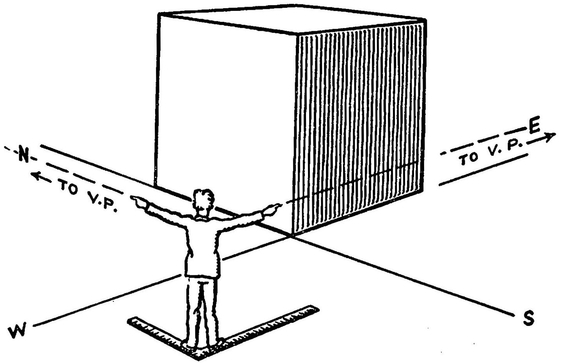

Stand in front of a cube (a brick or a building) and point arm’s length in the direction parallel with one side of the cube. Let us assume that you are pointing toward the east. Now then, the adjoining side of the cube runs northward. Point in that direction with the other hand. You are now pointing at the two vanishing points of the cube.

Your two arms form a square corner (right angle).

If the cube is turned the vanishing points will change their positions. You must now turn your body to meet these new directions. Your arms still form a square corner.

When the position of the cube is changed the relationship of the points must change. Let us see what this relationship is.

THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE TWO POINTS

First Position

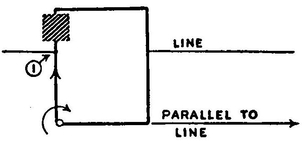

There are technical ways to determine the relationship between the two vanishing points, but for freehand drawing it is necessary to remember only the simple arrangement: a straight line; a sheet of paper tacked at the corner a short distance from this line.

The diagram above shows this arrangement; the tack represents the place where you are standing and the two sides of the paper show the directions of your outstretched arms. This is the same arrangement as the diagram on page 59.

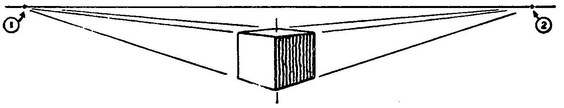

Now revolve the paper around the tacked corner so that the distance from the tack to the line is the same along the two edges of the paper (first position). Mark the two points where the edges cross the line (1) and (2).

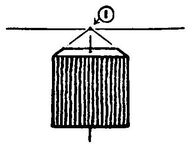

These two points represent the relationship of the two vanishing points when a person is looking directly toward the corner of. a building or any square-cornered object.

In a perspective drawing this line on which the two points lie represents the eye-level.

Above is the corresponding perspective drawing in which the object that is drawn has its vanishing points in the same arrangement as they are in the diagram—equally distant from the center.

Notice that the lighted and the shaded side of the cube appear the same in size.

We shall now change the position of the points: we shall notice how they move apart from each other and we shall see how the perspective drawing of the cube changes to meet these different positions.

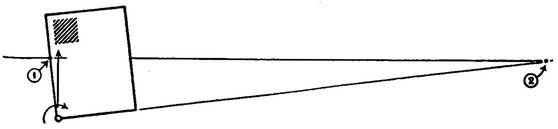

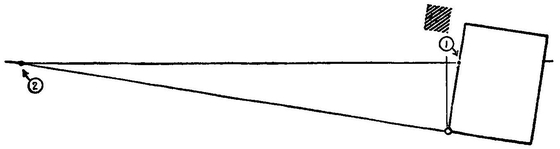

Second Position

Revolve the paper from the first position on the preceding page to the second position as shown above. Point number one moves toward the center which is directly above the tack.

Point number two moves away from this center at a much faster rate.

The cube is shown drawn with the vanishing points in this relationship.

Third Position

When the paper is revolved so that point number one reaches the center, point number two disappears. This is like the drawing of the railroad track where we have one-point perspective.

The line that determines point number two does not cross the line which represents the eye-level. Hence, no point.

Here we have a drawing of the cube in this relationship of points. The cube has a single side facing us with the top drawn in one-point perspective.

This is the arrangement of perspective points that we use in making a sketch of a room while standing at the center and directly facing a wall.

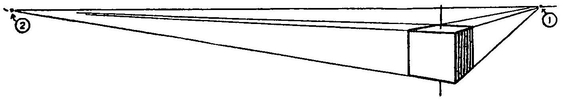

Fourth Position

Now revolve the paper still farther. Point number one passes the center and immediately point number two appears again on the line but in the opposite direction from its former positions.

The cube drawn to this arrangement is like position number two except opposite in direction.

Remember in using this method that the diagram of the line and sheet of paper is not a perspective drawing but merely a method of showing how the two vanishing points may be moved in relation to each other—one moves slowly, and the other quickly.

It shows also that the two points should be spaced widely apart in a perspective drawing.

Notice that we cannot have both points on the same side of the drawing. As soon as we turn the cube in order to create that relationship we find that the point passes to the other side. One perspective point is on the left and the other on the right of the center of interest. This relationship does not hold, of course, in one-point perspective.

REMEMBER

When you point in the same direction as the line you are sketching, you are pointing toward the vanishing point of that line.

The two vanishing points lie on the eye-level line out in the direction of the two lines forming the square corner on which you stand.

As the object is turned this corner revolves around the point on which you stand. You can thus follow the change in direction of the points.

The two vanishing points hold opposite sides of the center of interest. They cannot get together.

PROBLEMS

Place books so that they lie in different positions on your desk. Now point toward the vanishing points of each book.

Make a drawing of a box and then show how its vanishing points would be determined by the diagram.

Reverse the process by choosing one of the four positions of the diagram and then making the drawing accordingly to meet this condition.